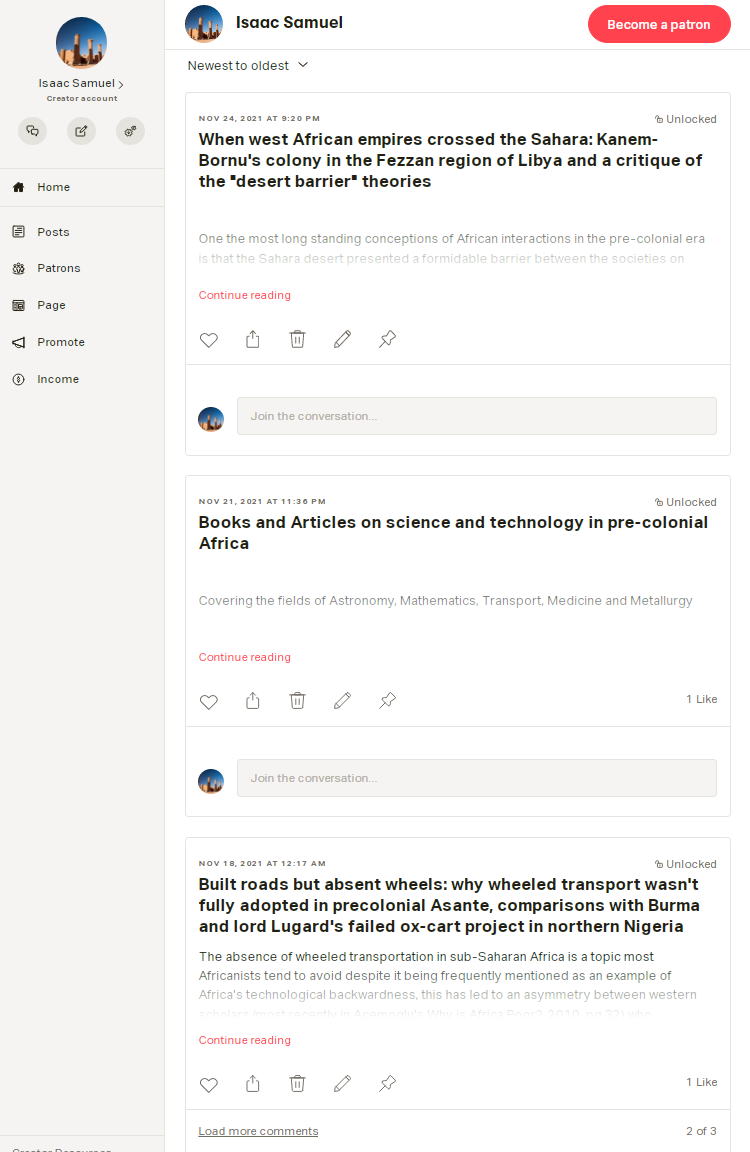

Science and technology in African history; Astronomy, Mathematics, Medicine and Metallurgy in pre-colonial Africa

On ancient Africa's accomplishments in Science, Technology, Engineering, and Mathematics.

Most of us have a fairly intuitive understanding of the terms science and technology within our modern context (ie from the 20th century onwards), but much of what we understand about modern science can't be easily defined across different time periods and societies making the terms themselves a source of anachronism in the study of pre-modern science and technology because we tend to highlight the things about pre-modern science that we recognize and ignore those that seem incomprehensible to us. Simply defined, science is, according to George Sarton: “the acquisition an systemization of positive knowledge” of which "positive" means information derived empirically from the senses, while technology is the application of scientific knowledge for practical purposes.1

Africa during and after the Neolithic era witnessed the emergence of large complex states many of which were fairly urban, covered vast swathes of territory and had large populations, sustaining these states necessitated the production of scientific knowledge and the application of technology by Africans to grow their societies, economies, militaries, etc. Save for the sole exception of metallurgy, studies of African technologies have received little attention leaving gaps in our understanding of how African states sustained themselves, how African architecture, intellectual traditions, agriculture, transportation, warfare, medicine, astronomy and timekeeping, were applied to improve the lives of Africans in the states that they lived in.

A central feature of African science and technology were the dynamics of invention and innovation, the former refers to the initial appearance of an idea/process while the latter refers to the adaptation of an invention to local circumstances.2 The robustness of science and technology in the different African states -as in all world regions- was dictated by the interplay of these two dynamics. Invention, which occurs less commonly in world history, requires a much longer time scale, sufficient local demand and a degree of isolation. In Africa, invention primarily occurred in metallurgy (iron, copper smelting, lost-wax casting) in glass making, forms of intensive agriculture among others. Innovation occurs much more frequently in world history and is responsible for much of the technological progress we see today, in Africa, it occurred in writing, warfare, architecture, textile manufacture, astronomy, medicine, mathematics, among others.

Because science as an orderly and rational structure (and the technology with which it was applied) predates writing, we can begin this article on the history of science and technology in Africa by looking at the oldest technologies and then cover the written sciences.

Support AfricanHistoryExtra by becoming a member of our Patreon community, subscribe here to read more about African history, download free books, and keep this newsletter free for all:

African Technologies: on their invention, innovation and use in early industry, agriculture and construction.

Metallurgy: on the use of metals in African history

Due to the geographical diversity of Africa, the process of extracting metals from their ores on the continent begun at different dates in different locations and using different methods. Nubian metallurgy begun with the smelting of copper and its alloys in 2200BC at Kerma while the smelting of Iron was established by 500BC at Meroe. In West Africa, copper smelting was present in Niger by 2000BC in the region of Termit massif, iron would later be smelted in the same region by 800 BC. In the rest of Africa, the advent of metallurgy begun in the early first millennium BC (save for some exceptional dates from Obui in the central African republic and Leja in Nigeria older than 2,000BC), it started with the working of iron at Taruga (Nok neolithic, Nigeria) between 800BC and 400BC, at Rwiyange (Urewe neolithic, Rwanda) in 593BC, Otoumbi in Gabon between 700BC and 450BC, and dozens of other sites across the continent in the second half of the 1st millennium BC such that by the turn of the common era, virtually all regions in Africa had an iron age site. The diffusionist hypothesis that iron was introduced from Carthage or Meroe now only stands on a purely conjectural theory that iron couldn't be smelted without prior knowledge of copper and bronze smelting, even after recent dates showed west and east African iron working was contemporaneous -and in some cases arguably earlier- than its established dates in Carthage and Meroe (where it supposedly originated) and which all fall between 800BC-600BC. As archeologist Augustin Holl writes "the very diversity of African metallurgical traditions escapes a purely taxonomic approach… chronologies that appear to run counter to the prevailing idea of diffusion are often disregarded, the question is whether this rejection is based on reasonable interpretation of the evidence at hand or is simply unwillingness to accept evidence contradicting long held ideas".3

The smelting of other metals such as gold and tin begun slightly later; after the mid 1st millennium AD in various places from Jenne jeno to Mapungubwe, lead smelting appeared in some places like Benue in Nigeria in the late first millennium and the DRC is the seventeenth century. Tin and copper were alloyed to produce bronze in the late first millennium in Nigeria and mid second millennium in south Africa. at Rooiberg where an estimated 180,000 tonnes of rock were mined to extract 20,000 tonnes of Cassiterite 4

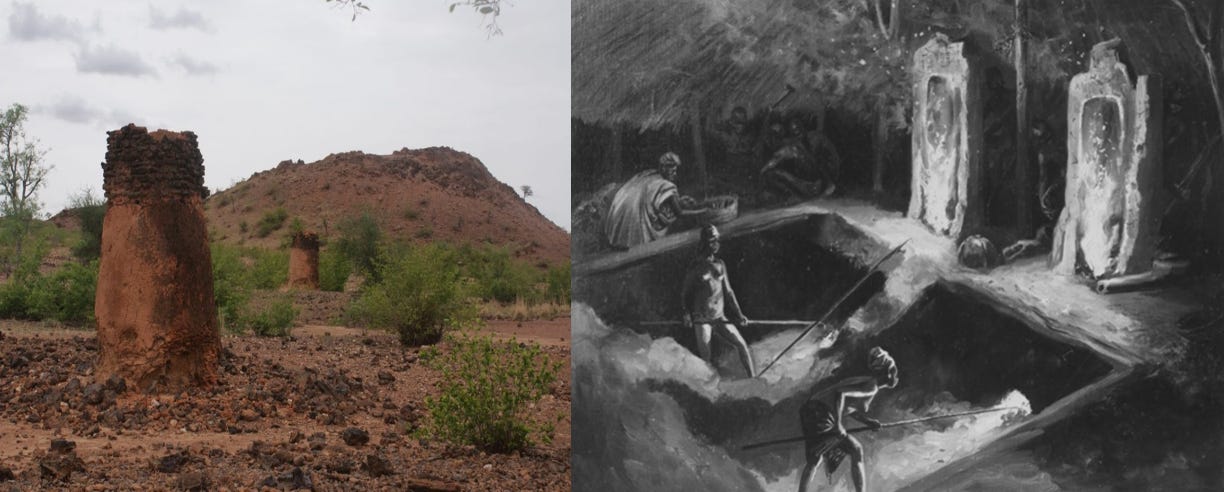

Iron was used for utilitarian purposes while copper and gold were used in ornamental jewellery, besides the high demand for iron weapons and armor from the militaries of African states see my article on "war and peace in ancient and medieval Africa” the largest demand for iron in Africa was for domestic implements from farm and mining tools to kitchenware, this made blacksmithing a fairly common profession in many regions of Africa and turned made blacksmiths a relatively privileged caste in some. Improvements in African furnaces happened in the shift from using shaft and bowl furnaces to using natural draught furnaces by the late first millennium AD which had superstructures upto 7m tall and allowed for the smelters to remove the slag as it accumulated.5

Specialist metal smelting and forging centers could be located within cities such as in the Hausalands, along the Swahili coast and just outside the city of Meroe where 10,000 tonnes of slag were found, and also in rural settings, where the quantities were just as substantial eg 60,000 tonnes of slag were found at Korsimoro in Burkina Faso, more than 40,000 furnaces were located in an 80km belt along the middle Senegal valley6 and Sukur smelters of Northern Cameroon forged over 60,000-225,000 hoes annually.7 Iron was also exported by African surplus producers such as the Swahili who are known to have produced high-carbon crucible steel and cast iron in their bloomeries, according to the historian Al-Idrisi (d. 1165AD), the Swahili cities of Mombasa and Malindi produced large quantities of iron that formed their main export which was shipped primarily to south India.8

<left picture> rural natural draught furnaces in Burkina Faso from the early second millennium, <right picture> an urban two story furnace from ile-Ife, Nigeria illustrated by Carl Arriens in 1913

Another salient aspect of African metallurgical technology was in coinage, jewellery and other forms of ornamentation where African gold, sliver and bronzesmiths achieved the highest level of sophistication and mastery.

Gold, which was a major African export throughout the pre-modern era, was refined in places such as in the city of Essouk in Mali managing to attain upto 99% purity, the process of refining it involved crushed glass and this essouk industry flourished between the 9th and 11th centuries9, cast and sheet gold was also fashioned into jewellery in various places on the continent but most notably among the Asante where some of their masterpieces include the soul washers badges, gold weights and ornaments which were made with intricate designs. gold was also struck into coinage in local mints in various cities across the continent, from Aksum in Ethiopia, to Kilwa in Tanzania to Nikki in Benin using various molds that were unique to each city.

Copper alloys were perhaps the most commonly used metals in ornamentations, at Ife, a number of highly naturalistic life size heads were fashioned out of pure copper in the 13th-14th century using the lost wax method, an impressive feat given copper's higher melting point than its alloys and is more difficult to cast with only few sculptures in the ancient world cast in pure copper10. Copper-alloys, especially bronze, were far more common and were the primary material for ornamentation across Africa from Nubia to Igbo Ukwu, from southern Africa to central Africa. The most common manufacturing technologies employed in the casting of African gold, copper-alloy and silver-works were: the cire perdue (lost-wax casting), Repousse casting and riveting. Examples of applications of these casting technologies include the Meroitic bronzes of ancient Kush, the Benin brass plaques, the Akan gold discs, masks and ornaments, the Mapungubwe gold artifacts, etc

<Left picture> gold disk; Asante soul washer’s badge from the 19th century (British museum), <Right picture> bronze wine bowl from Igbo ukwu from the 9th century (NCMM Nigeria)

Glass manufacture: innovation and invention in African glassware

Practical and decorative glass objects are a common occurrence in African history, mostly in ornamentation in the form of glass beads but also in domestic settings eg glass vessels and in architecture eg windows.

Independent invention of glass in Africa was undertaken in the city of ile-Ife in south-western Nigeria beginning in the 11th century, Ife’s glass has a distinctive high lime, high alumina content and was made using local pegmatite sands with manufacturing centers identified at Igbo Olukun and later at Osogobo in the 17th century, the glass beads made in Ife circulated widely in west Africa especially in the ancient capitals of Kumbi-Saleh and Gao in the 12th century, the city of Essouk and at Igbo ukwu.11

HLHA glass beads made at ile-Ife, Nigeria dated to between the 11th century and 15th century

Secondary glass manufacture and repair was a more common industry across Africa, the increasing importation of glass vessels, glass beads, glass panels and their use in ornamentation, domestic settings and elite architecture led to the development of a vibrant local glass industry that produced and reworked glass objects better suited for local tastes. There’s evidence of a glass industry in the kingdom of Kush especially during the Meroitic era with the presence of raw glass at Hamadab and the unique Sedeinga goblets.12 and a similar glass industry in Aksumite Ethiopia based on the presence of raw glass found at Aksum, Ona Negast and Beta Giyorgis 13, and evidence of a glass industry in the kingdom of Makuria as well, based on the presence of numerous fragments of glass vessels and raw glass found at Old Dongola.14

The presence of local glass industry may also be inferred from the recovery of glazed window panes alongside glass vessels and beads many of which were locally reworked in a number of cities such as the palace of Kumbi Saleh (Ghana empire) as reported by al-idrisi (d. 1165), and in archeological digs at Essouk and Gao15 and Ain farah16 (Tunjur Kindom). The most common re-workings of glass across Africa were glass beads, such workshops are attested across virtually all African regions most notably at Gao Saney17 and k2-Mapungubwe in south eastern Africa.18

<Left picture> glass flute made in Kush around 300AD, from Sedeinga, Sudan (at the sudan national museum). <Right picture> glass goblet made in Aksum in the 3th century (at the Aksum archaeological Museum)

Textiles: on the technologies used in African cloth industries

As one of the biggest handicraft industries in pre-colonial Africa cloth making also had some of the most diverse techniques used in manufacturing, the most common being the hand-operated weaver's looms, of these looms, the most efficient was the pit treadle loom which operated with spinning wheels and the vertical loom which operated with foot pedals, others included the ground loom.

The production capacities of African weavers were substantial as I covered in my article on “Africa’s Urban Past and Economy", just one Dutch purchase of benin cloths in 1644 involved 96,000 sqm of cloth from benin which was only a fraction of benin's cloth trade while in west-central africa, exports to the portuguese colony of angola from the kingdoms of kongo and loango involved more than 180,000 meters of cloth annualy rivaling contemporaneous production in other world regions.

<left> Cotton spinning somalia 19th century, <right> hausa weaver working on a vertical loom in Nigeria

Agriculture: On intensive farming in Africa

Several African states and societies used a number of methods of intensive agricultural technologies to sustain their large populations, these methods included, ox-plow agriculture, dry-stone terracing, mechanical water-lifting and other forms of irrigation such as channeling.

In ancient Kush and medieval Nubia, intensive irrigation farming involved the use of the saqia water wheel, this animal-powered wheel could lift Nile river water upto 8 meters, enabling the sustenance of agriculture in an otherwise semi-arid Kushite territories of upper nubia and later in the Dongola reach which was Kush’s heartland, added to this were the older water harvesting methods called Hafirs; these were large artificial water reservoirs measuring up to 250m in diameter and storing as much as 200,000 m3 that were dug in arid regions of the kingdom of Kush, with as many as 800 of them constructed in Sudan between the 4th century BC and 3rd century AD, these Hafirs significantly extended the kingdom's reach into the surrounding desert regions. Kush’s intensive agricultural tradition continued into the medieval Nubia era and the muslim era under Darfur and Funj kingdoms where extensive plantations were sustained using various forms of irrigation. similar water conservation systems were built during the aksumite era such as the safra dam in eritrea.19

<left> A Nubian sakia wheel in the mid-19th century, <right> Safra dam in Qohayto, eritrea

In Aksum and Ethiopia, oxdrawn plows, drystone terracing was well established between the 1st and 4th centuries AD, increasing in the medieval era, agricultural productivity was the backbone of medieval Ethiopia's economy especially in the highland regions. In eastern Africa, intensive agriculture was carried out by both state level and non-state level societies, primarily using dry-stone terracing and furrow irrigation most notably at Engaruka in Tanzania. In southern Africa, the most notable intensive agriculture occurred at Nyanga in Zimbabwe and the Bokoni of South Africa, using dry-stone terracing and irrigation, these regions supported substantial settlements with an estimated 57,000 people in a narrow 150km corridor along the highveld escarpment in Mpumalanga that exported surplus grain to surrounding regions. In west Africa, intensive farming was used in a number of regions most notably; flood recession and water-lifting farming in the inland Niger delta (this region was the agricultural heartland of the Mali and Songhai empires) and the dry stone terraces of northern Cameroon particularly at DGB.20

The construction and maintenance of these intensive farming methods across these African states involved significant amounts of labor, a degree of mechanisation and an understanding and documentation of seasonal variations in rainfall, this was perhaps best documented in the kingdom of Kush where floods were recorded21 and the level of the Nile was measured to predict planting seasons and floods.

Warfare: On the technology of African weapons, armor and fortifications

As covered in my article on "War and peace in ancient and medieval Africa" some of the most robust application of science and technology were employed in African warfare involving both the invention and innovation of weapons, armor and defensive systems. These innovations and inventions can be seen from the early use of ancient missile weapons such as flaming and poisoned arrows, to the adoption of cross-bows, muskets and cannons, from the the various inventions of close-combat swords, lances and daggers to the adoption and manufacture of gunpowder, and lastly defensive/static warfare technologies can also be seen from the construction of massive fortification systems across Africa including towering city walls sheltering hundreds of square kilometers of residential and agricultural land, these fortresses were attimes sieged and taken by armies using raised platforms on which were stationed musketeers or archers, and in a few cases, the walls and gates were blown up using gunpowder and cannon fire.

Construction: On the technology used in African architecture and engineering

African architecture involved various materials and techniques in the construction of large residential, palatial andreligious buildings, many of Africa’s architects and masons applied standardized measurements and instruments in construction, this was especially evident when the materials for construction was sandstone, fired-brick, coral-stone, mud-brick, mortared stone and dry-stone which were used across the continent in hundreds of African cities. As covered in my article on African architecture in "Monumentality, Power and functionalism in Pre-colonial African architecture" the different styles of African architecture were dictated by various functional needs, aesthetic choices, building materials and the levels of; cosmopolitanism, population and urbanisation. Depending on the construction material and climate, some of the earliest African roofs were flat roofs that were used across various regions eg in southern Mauritania, the inland Niger delta in Mali, the Hausalands, Lake chad basin, ancient and medieval Nubia, Aksum and medieval Ethiopia, the Benadir coast and the swahili coast, other African roofs were high pitched set ontop of rectilinear houses eg in southern Nigeria, Ghana, most of west central Africa and parts of southern and eastern Africa all of which are in more humid climates. These rectilinear houses allowed for more living space and the need to house even higher populations with the confined spaces of large African cities required the construction of storey buildings, this was enabled by the use of mortar (although storey construction could be achieved without mortar eg at Aksum), such superstructures were supported using columns of both stone and timber, and thick walls.

In the inland Niger delta region, southern Mauritania and the Niger bend, the two-storied house became a staple for elite housing best attested in the cities of Djenne, Dia, Timbuktu, Mopti, Segu and Gao. Such buildings typically used the terraced upper floors as living quarters and lower floors as servants quarters and receptions. The same pattern of construction for storey buildings can be observed in the Hausalands, while in ancient and medieval Nubia, houses, dormitories and castle-houses had multiple stories especially in the cities of old Dongola, Karanog and Faras, the same was also observed in the Ethiopian cities of the Aksumite era especially at Adulis and Aksum itself, and a number of medieval settlements in the northern regions especially in Tigray and later more famously at Gondar. Perhaps the most ubiquitous occurrence of similar multistory housing was in the cities of the east african coast especially Mogadishu, Pate, Kilwa, Lamu, Mombasa and Zanzibar.

a city section in djenne with double-storey residential homes

sections of the cities of Zanzibar (Tanzania) and Kano (Nigeria) showing double-storey residential houses

Inorder to maximise open space, African architects also used vaulted and domed ceilings, such were present in the Hausalands, in ancient and medieval Nubia, in Aksumite and gondarine Ethiopia, and in the Benadir and Swahili coastal cities the arches, domes and vaults being constructed using coral stone and mud-brick.

the great mosque of kilwa, Tanzania built in the 11th century, with a barrel vaulted ceiling

Inorder to maintain sanitary cities, various designs of indoor lavatories, bathrooms, under-floor heating are attested in a number of African cities. The combination of these three was a feature of medieval Nubian and Aksumite elite housing; Nubian toilets were made of fired-clay ceramic bowls, with one serving as a water closet and another for seating, the refuse was flushed out with hot water through a ceramic pipe into a vaulted cesspit underground22, while an indoor toilet and bathroom superstructure, built over deep latrines and/or cesspit were a feature of urban construction in the Swahili cities (eg at Shanga and Gedi23), the cities of ancient Ghana (eg Kumbi saleh24), in the Inland Niger delta cities (eg jenne-jeno25) and Niger-bend cities (eg Timbuktu and Gao26) and the Asante cities (especially in Kumasi27). Other aspects of African construction are the construction of defensive and monumental architecture like the walls of great Zimbabwe and the palatial residences of Husuni Kubwa, Kano, Gondar and the palaces of Benin, Kumasi and Dahomey, the baths of Meroe, Gondar, the rock-hewn temples of Lalibela and the public courtyards of the Comorian cities.

<left> top story toilet in a house at Kumasi, Ghana from Thomas Bowdich’s illustration, <right> a lavatory a house at Gedi, Kenya (archnet photo)

Transportation: On technological innovations in African maritime and overland travel

The bulk of African innovation in transport occurred in water-borne transportation, particularly along the eastern African coast where maritime trade was important for the coastal states from Aksum in Ethiopia to Adal and Mogadishu in Somalia, down to the Swahili coast; both for commercial and military purposes (for African maritime warfare, see the section on African armies and warfare in “War and Peace in ancient and medieval Africa”) . a number of ship-building centers existed especially at the Aksumite port of Adulis in the 6th century28, and along the Benadir and Swahili coasts from the early 1st millennium29, Aksumite ships sailed as far as sri-lanka30 while Swahili mtepe ships and Somali beden ships travelled well into the Indian ocean to southern Arabia, southern India and possibly the Indonesian islands where Swahili traders from Mogadishu, Kilwa and Mombasa were active at Malacca the 16th century31, the ships varied in size and number of sails, the most common mtepes had square sails and had a capacity of 20 tonnes.

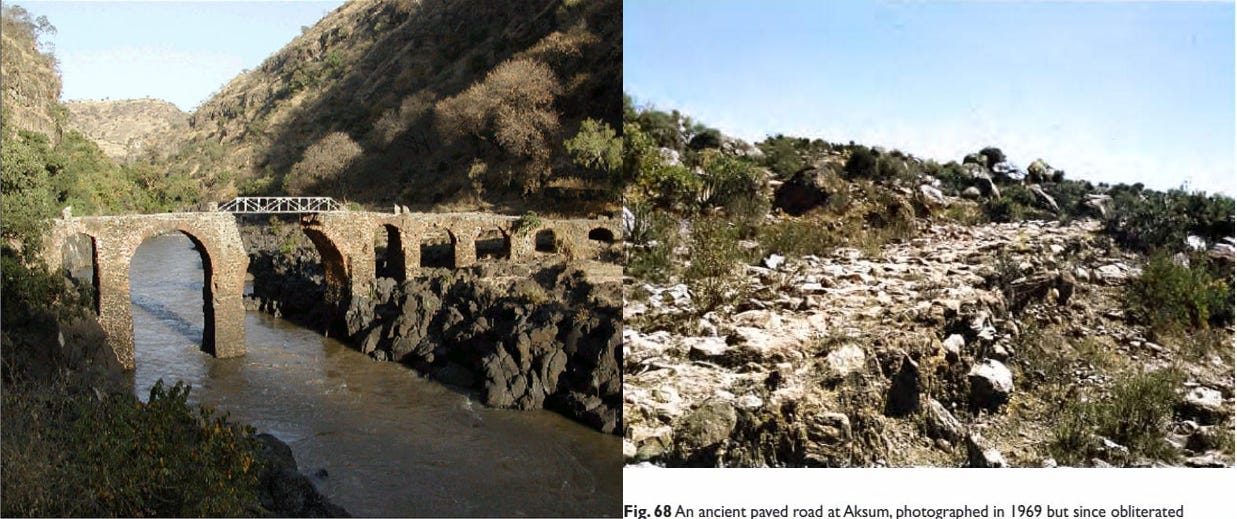

In overland transportation extensive road networks were constructed by the Aksumites and the Asante. Aksum’s roads were paved and ran along interior trade routes eg the road described in the Monumentum Adulitanum that ran from Aksum to the Egyptian border (likely at philae) and along the red sea coast these roads were primarily for centralizing the state and keeping conquered tributaries in check but may have also served commercial purposes 32. Asante’s roads radiated out of kumasi and served to secure trade routes and centralize Asante's power, these roads -which consisted of 8 major roads/highways and dozens of minor roads- were constructed at state expense which endeavored to repair them annually and maintain a highway police that was stationed along major roads to keep them secure, these roads also had rest-places for lodging travelers.33 In gondarine Ethiopia, several bridges were built to enhance the capital's prominence, ease transportation of armies from the capital to the various provinces and improve trade routes.34

<left> a gondarine-era bridge on the blue Nile, built by emperor fasilidas in 1660 but blown up during the Italian invasion of 1935, <right> an ancient paved road at Aksum; both in Ehiopia

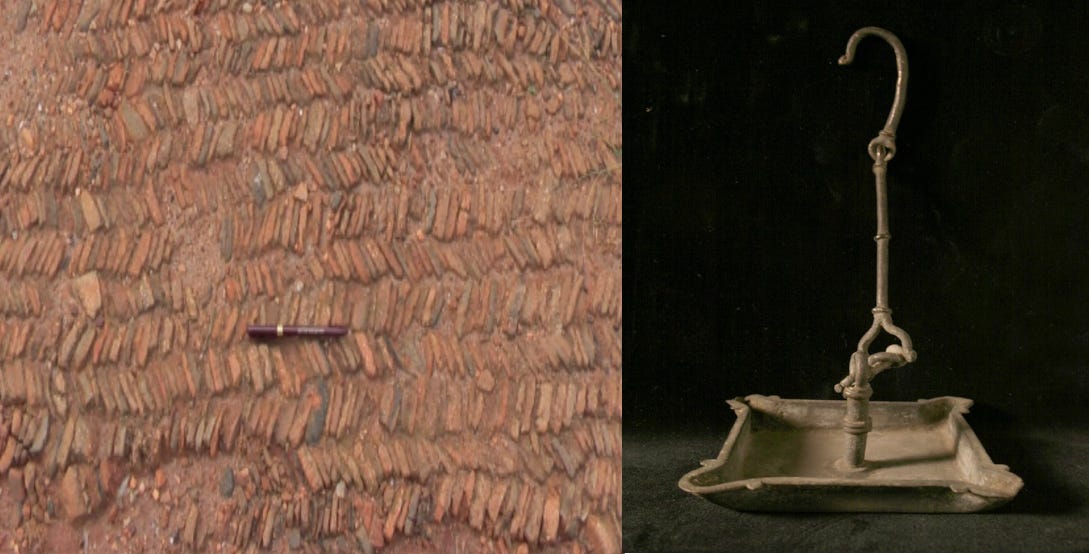

Extensive street paving was used in many west African cities, wide streets were raised and their surfaces fitted with broken potsherds that were neatly laid using various patterns, the technology may have originated in the ancient city of ile-Ife and occurs widely in both the Sahel and the forest region of west Africa from Jenne-jeno in Mali to Dikwa in north eastern Nigeria35. Other miscellaneous feats include street lighting in Benin city and indoor lighting in various Swahili and eastern African cities that included wall niches for placing lamps.

<left> potsherd paved street in Ife, <right> oil lamp from Benin city; both in Nigeria

Science; On the documentation and study of scientific disciplines in Africa.

As shown by its application above, science was a central feature of African society, both written and oral accounts attest to its study, innovation and application. Scientific disciplines were part of the school curriculum in west Africa, Sudan, Ethiopia, the horn of Africa and the east African coast, these disciplines taught included mathematics, astronomy, medicine and Geography, and these are just from the written records, the oral history also attests to a disciplined undertaking of the study of sciences especially in medicine and astronomy across a wide variety of african cultures, and the archeological evidence from African ruins also attest to the existence of a rigorous application of learned sciences especially mathematics in construction.

Mathematics: On the documentation and application of mathematics in Africa

Archeologically, one of the best evidences for the application of mathematics in Africa comes from the kingdom of Kush where a large engraving depicting a pyramid was drawn on the chapel of a pyramid (number BEG N8), the engraving measures about 1.68meters in height (ie it was reduced to the scale of 1:10 compared to the normal Meroe pyramid height), and it depicts 48 perfectly straight lines running vertically across the pyramid separated at a distance of 5.25cm (ie: a tenth of a cubit) and two diagonal lines climbing from the base of the engraving to a capstone at the top, angled at about 72 degrees, thus giving a base to height ratio of 8:5 (ie: the golden ratio, that was used for structural and aesthetic purposes in ancient architecture) based on this plan, the engraving was drawn for the construction of pyramid BEG N2 for King Amanikhabale, thus dating it to around 40BC. The center line in the engraving was also essential to the construction of the pyramid as supervisors of pyramid masons used this line to maintain symmetry and structural integrity of the pyramid during construction. The sheer number of Meroitic pyramids, their fairly uniform construction and this engraving are all evidence of the extensive use of mathematics in Kush's architecture.36 and as discussed below, this application of mathematics in Kush also extended to astronomy. I discussed the mathematics of this pyramid in detail on my patreon.

Hinkel’s illustration of the Meroe engraving and its interpretation

More common evidence for mathematics in Africa were the mathematical manuscripts especially those dealing with "magic" squares, one of the extant works on these was that written in 1732 AD by an astronomer and mathematician named Muhamad al-Kishnawi al-Sudan, who was born (and studied) in Katsina (Nigeria). The work is titled :"Mughni al-mawafi an jami al-khawafi" and it deals with formulas for solving magic squares with odd number of rows; 5×5, 9×9, 11×11 and is specifically addressed to math students with encouraging words: "Do not give up, for that is ignorance and not according to the rules of this art. Those who know the arts of war and killing cannot imagine the agony and pain of a practitioner of this honorable science. Like the lover, you cannot hope to achieve success without infinite perseverance", al-Kishnawi was taught mathematics by his tutor Muhammad Alwali of the kingdom of Bagirmi in Chad37 Similar magic squares can be found across various African scholarly centers eg in Ghana (especially from Kumasi), in guinea (at Timbo), in Mali at Djenne and Timbuktu, in Ethiopia at Harar, and in Kenya and Tanzania at Lamu and Zanzibar.

al-Kishnawi’s “Mughni al-mawafi” (now at the Khedive library cairo)

Astronomy: On an African astronomical observatory and astronomical manuscripts

Astronomy perhaps the oldest attested science in African history, occurring from as early as the 9000BC Nabta playa and the various stone circles and monuments across the continent, and continuing well into the era of African states in antiquity most notably in the kingdom of Kush and extending into the medieval and modern era with the creation of various solar and lunar calenders and the study of astronomy as a discipline in the various intellectual centers of Africa eg Djenne and Timbuktu in Mali and Lamu in Kenya.

On the world's oldest observatory; a building complex dedicated to the study of stars in the city of Meroe

Archeologists discovered a set of three buildings constituting a complex that was exclusively dedicated to the study of star movements in the ruins of the city of Kush. The top building in this complex served as the observatory and had engravings of quadratic equations written in cursive meroitic on one side of its walls, on another wall was an engraving of two figures with one sited and another assisting to handle a large wheeled instrument pointed at the sky, and a lastly on the room’s floor was a square pillar on which was inscribed a bisected isosceles triangle angled at around 76 degrees. All archeologists who worked on the site and historians who studied the engravings and the building complex concluded that it was strictly of astronomical nature, this was first identified by John Garstang immediately during excavation of the site in 1914, and later by nubiologist Bruce Williams in 1997, egyptologist Leo Depuydt in 1998 and the nubiologists Thomas Logan and Laszlo Torok in 2000 and 2011 respectively, Torok also identified an office of an official state astronomer who was tasked with measuring the hours and lengths of the day and nights and the seasons, as well as timing the Nubian feasts38. Also found in the lower rooms were large sandstone basins which according to Torok were used to preserve pure Nile water drawn at the exact time of inundation. The building is dated to the 1st century BC and is therefore seven centuries older than the Cheomseongdae observatory in Korea. I discuss the entire observatory and Meroitic astronomy in detail on my Patreon. including photographs of the site and building plans.

illustrations of the Meroe astronomical observatory’s engravings

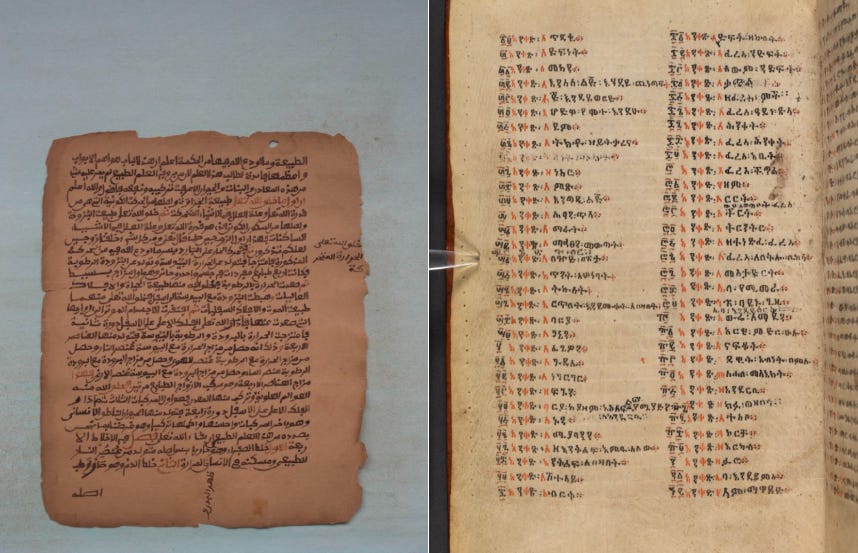

The better documented studies of African astronomy come from the medieval intellectual hubs of Africa, while few of the manuscripts have been studied, an estimated hundreds of them deal specifically with the discipline of astronomy especially on recordings of astronomical events such as the meteor shower of august 1583 AD that was recorded by the chronicler Muhammad al-kati in the Tarikh al fattash. The teaching of astronomy in African schools was necessitated by the need to make accurate calendars, guiding caravans across the Sahara and the seafarers in the Indian ocean, and determining prayer times. Astronomical manuscripts produced in Gao, Djenne, Timbuktu and Lamu often include illustrations of planetary orbits, the solar system, tabulation of days, weeks, months, star positions, directions to mecca, and other details.39

<left> Astronomical manuscript from Lamu, Kenya in the 19th century, astronomical manuscript from Gao, Mali in the 18th century <right>

Medicine; on the practice and documentation of medicine in Africa

Africa has an old history of medical traditions that grew out of African scientific observations of the environment and disease. Ethnographically and archeologically a wide variety of treatments, surgeries and healing practices have been recorded across a large number of African societies. The intellectual documentation of medicine in African history is also fairly robust with medical manuscripts making up a significant share of African scribal production especially in the old cities of Sokoto and Kano, Djenne, Timbuktu, in Ethiopia and the on the east African coast

Ethnographically, a number of cataract surgeries, inoculations (especially against smallpox) were observed to be widespread across most of Africa40 , treatments for malaria, guinea worm, treatment of wounds from poisoned arrows and gunshots, medical care for horses, diagnosis and treatment of hemorrhoids and eye infections, venereal diseases and skin diseases were also observed and written by African scholars.41

But perhaps the most famous of African medical practices witnessed was a caesarian section surgery performed in the kingdom of Bunyoro in western Uganda, involving banana wine both as an anesthetizer and a sterilizer for the expectant woman and the surgeon, a sharp blade was used by the surgeon to effect the cut across the abdomen, the baby was removed and the bleeding was stopped by careful cauterization using a hot iron, the wound was stitched together using small iron spikes and covered in a clean cloth. This process was observed by Robert Felkin, a British medical student during a missionary expedition to the kingdom, he later followed up with the mother and her baby; both of whom fared well during this time with the mother's stiches had been removed within 3-6 days. The surgeon worked with a team of two assistants who in all their operations, exhibited a high level of precision that could only have been achieved through years of experience. similar medical feats in Bunyoro were also observed in inoculation and medicine experimentation.42

illustration from Robert Felkin showing the young woman lying on the operating table, with the surgeon's assistant holding her ankles, as published in the Edinburgh medical journal in 1884

Africa’s written accounts on medicine, diseases and their treatment are also equally extensive, there are dozens of published and translated manuscripts from the 18th and 19th century on the treatments of eye diseases, skin diseases, venerial diseases and hemorrhoids using local medicinal plants by scholars such as al-Tahir al-Fallati an 18th century scholar from Bornu, and the Sokoto trio Abdullahi Fodio (d. 1828), Muhammad bello (d. 1837) and Muhammad Tukur (d. 1894) . These three scholars differed in approaches to medicine, with Bello and Tukur not objecting to the use of both Islamic and traditional medicine (especially Hausa medicine) while Abdullahi strongly recommended that practitioners stayed within the realm of Islamic medicine.43 In Ethiopia, several documents attest to an old medical tradition in the state, with lists of medicinal plants and herbs, lists and treatments of diseases, common ailments, wounds, etc. A number of these from the 18th and 19th centuries have been studied.44

Medical manuscripts from Sokoto, Nigeria written in the 19th century <left> and from shewa, Ethiopia written in the 18th century

Geography; On documentation of Topography, Mapmaking and descriptions of occupied space in Africa

A few manuscripts on geography from west Africa have recently received academic attention, particularly two that were written by a scholar from Sokoto, the first being ‘Qataif al-jinan’ (The Fruits of the Heart in Reflection about the Sudanese world" written by the philosopher, geographer and historian Dan Tafa (d. 1864) , the work provides a detailed account of the topography and history of West Africa, North Africa, Arabia, South India and the East African coasts. Dan Tafa uses information derived from pilgrims and travelers for the regions closes to him (west Africa and north Africa) and he quotes multiple medieval Arabic authors in his descriptions of the regions far from his homeland in northern Nigeria.45 Another geographical work was written by the same author titled ‘Rawdat al-afkar’ (The Sweet Meadows of Contemplation) written in 1824. Geographical writings were also produced in Ethiopia although none have been studied sofar46 Secondary information from explorers also attests to a knowledge of geography and Mapmaking by Africans especially the maps that were drawn by west African scholars who had been visited by the explorers Heinrich Barth in Sokoto and Thomas Bowdich in Kumasi.

Conclusion

Africa has a rich history of science and technology which unfortunately, has been largely neglected by academia. Few of the hundreds of manuscripts of scientific nature from west and eastern Africa have been studied and there have hardly been any studies on African architecture and engineering on Africa’s ancient ruins beyond cursory observations and mentions by archeologists. Discourses on African technologies and sciences, for example in metallurgy, should move beyond debates on its genesis and instead explore the extent of the production and use of metals in past African societies and early industries, African medical manuscripts should also be studied to complement modern medical practices. Africa’s scientific and technological legacy offers us not just a peek into the African past but a foundation on which modern innovations and studies in STEM can be situated better within the African context.

A special thanks to the generous supporters of this blog on my Patreon and Paypal, i’m grateful for your contributions.

Read more on African history and African astronomy and download books on African history on my Patreon account

Science and Technology in World History, Volume 1 by D. Deming, pg 7

A global perspective on the pyrotechnologies of Sub-Saharan Africa by D. Killick pg 79

Ancient African metallurgy by A. F. C. Holl et al. pg 12-16

D. Killick, pg 75

metals in past societies by S. Chirikure pg 65-67

D. Killick, pg 72

Aspects of African Archaeology, pg 197

Society, Culture, and Technology in Africa, Volume 11 by S. T. Childs, pg 64

Refining gold with glass by T. Rehren, S. Nixon

Art and Risk in Ancient Yoruba by S. P Blier, pg 273

Chemical analysis of glass beads from Igbo Olokun, Ile-Ife (SW Nigeria) by A. B. Babalola

'Glass from the Meroitic Necropolis of Sedeinga. by J. Leclant, pgs 66-68. and; The Oxford Handbook of Ancient Nubia By B. Williams, pg 528

Foundations of an African Civilisation by D. W Phillipson pg 162-165

The Oxford Handbook of Ancient Nubia by B. Williams pg 853

Essouk - Tadmekka by Breunig, Magnavita, Neumann, pg 158

Sudan Notes and Records, Volume 33, pg 259

Trade in the Ancient Sahara and Beyond by D. J. Mattingly et al, pg 110

The Emergence of Social and Political Complexity in the Shashi-Limpopo Valley of Southern Africa, by CM Kusimba pg 48

State formation and water resources management in the Horn of Africa by F Sulas pg 8

The Archaeology of Agricultural Intensification in Africa by Daryl Stump

The Double Kingdom Under Taharqo by J.Pope pg 133

The Medieval Kingdoms of Nubia by D. A. Welsby, pg 171

Shanga by M.Horton pg 58

Recherches Archéologiques Sur la Capitale de L'empire de Ghana by Sophie Berthier

Excavations at Jenne-Jeno, Hambarketolo, and Kaniana (Inland Niger Delta, Mali) by S. McIntosh pg 45,

Discovery of the earliest royal palace in Gao … by S. Takezawa

Mission from Cape Coast Castle to Ashantee by T. Bowdich, pg 306

economic history of ethiopia By R. Pankhurst pg 276-278

The Archaeology of Seafaring in Ancient South Asia By H. P. Ray, pg 59-62

D. W Phillipson, Pg 200,

East africa and the dhow trade by E. gilbert

D. W Phillipson, Pg 179-80, Aksum and Nubia by G. Hatke, pg 59-61

Asante in the Nineteenth Century by i. Wilks, pg 1-42

R. Pankhurst, pg 74-75

Mobility and archeology along the eastern arc of Niger by A. Haour

The Royal Pyramids of Meroe by Friedrich W. Hinkel

Africa counts by C. Zaslavsky pg 138-151

The Kingdom of Kush by L. Torok, pg 473

African cultural astronomy by J. Holbrook pg 179-187

African ecolongy by C. A. Spinage pg 1244-8)

The history of islam in africa by N. Levtzion pg 480)

The development of scientific medicine in the African kingdom of Bunyoro-Kitara by Davies J.

Islam, Medicine, and Practitioners in Northern Nigeria by A. Ismail pg 98-114

An Introduction to the Medical History of Ethiopia Richard Pankhurst

A Geography of Jihad. Jihadist Concepts of Space and Sokoto Warfare by Stephanie Zehnle pg 85-123

Catalogue of the Ethiopic Manuscript Imaging Project, by Melaku Terefe, pg xix

I just read this, fascinating work. I wonder if we can get more literary descriptions of innovation and technology, as opposed to archeological evidence, from Arabic sources. From homegrown writing in Ajami and probing into the forest regions earlier than usually discussed I mean.

Fantastic essay as usual Isaac!