Self-representation in African art: the wall paintings of medieval Nubia. (ca. 700-1400)

an African portrait of an African society

Many of the representations of Africans in popular art history were made by non-Africans, such as the landmark publication series, 'The Image of the Black in Western Art' which contains thousands of images of Africans drawn by artists living outside the continent. However, most of these artists' representation of Africans reflect an external perspective of African society that doesn't capture authentic African forms of self-representation.

The region of ancient Nubia in what is now northern Sudan was home to some of Africa's oldest art traditions. African artists in the kingdoms of Kerma and Kush, adorned the walls of their temples with paintings of various personalities across Nubian society, from royals to priests to subjects. After the fall of Kush, the kingdom of Makuria dominated medieval Nubia and developed its own art traditions.

Makuria's artists created one of Africa's largest corpus of wall paintings depicting Africans from across the kingdom's social hierarchy. This unique collection of African self-representation provides us with an internal perspective of how Africans perceived their own society. From the paintings of royals and clergy to common subjects, the wall paintings of Makuria are a portrait of a medieval African society as drawn by an African.

This article outlines the history of African self-representation in the wall paintings of medieval Nubia.

Support AfricanHistoryExtra by becoming a member of our Patreon community, subscribe here to read more about African history, download free books, and keep this newsletter free for all:

Brief history on the foundation of Nubian art traditions

Beginning in the 8th century, the kingdom of Makuria developed a dynamic art tradition in the form of vibrant murals which adorned the walls of ecclesiastical buildings. The number of paintings varied according to the size and the religious and political importance of the buildings, and many of the painted scenes located in specific places in the churches and monasteries bear witness to the existence of a basic iconographic program followed by Nubian artists.1

Nubian artists relied in part on iconographic models from the eastern Mediterranean world. These basic models which were widely used throughout the Christian world, were adopted in Nubia during the mid-1st millennium and subsequently modified in the development of local art styles. Arguably the most influential iconographic models during the early centuries of the development of Nubian Christian art came from the Byzantine empire, with which the region was in close contact.2

Recent archeological research indicates that the initial adoption of Christianity by the royal courts of Nubia (Noubadia, Makuria and Alwa) was a protracted process involving the gradual integration of the region into the Mediterranean world3. On the other hand, external accounts explain that Nubia’s Christianization was the result of a competition between the orthodox Byzantine Emperor Justinian and his miaphysite wife Theodora. A priest named Julian who'd been sent by Theodora, reached Nobadia first, then the king of Alwa sent an embassy to Nobadia requesting that Noubadia sends a priest to the southern kingdom. A bishop named Longinus eventually reached Alwa after some difficulty crossing Makuria. The adoption of Christianity in Makuria on the other hand, was a result of an embassy that the kingdom had sent to Constantinople in the reign of Justin II.4

Around the 7th century, the northern kingdoms of Noubadia and Makuria united both their governments and their churches, with Makuria becoming miaphysite. Byzantine Egypt was conquered by the Arabs, which cuts off direct relations between Constantinople and Makuria’s capital Old Dongola, but also closely ties the latter with the seat of the miaphysite/coptic church in Alexandria and the churches of Upper Egypt.5 Beginning in the 8th century, the spread of Christianity across Makuria is a result of the Nubian church, its priests and the royals. The kings of Makuria retain significant influence over the organization of the church, from its archbishops to the rest of the clergy who are often selected by the King at Old Dongola from local monasteries and were of Nubian origin. Churches in Noubadia are rebuilt in Makurian style by local architects such as the cathedral of Faras, and their walls are painted by local artists with various saintly and political figures, in an iconographic program that appears across all Makurian churches.6

The Makurian church became more “naturalized” beginning in the 10th century and by the 11th century, a marriage alliance between the royal families of Makuria and Alwa resulted in the unification of the two states into the kingdom of Dotawo. The same period sees an indigenization of Nubian church and court practices. This includes the widespread introduction of religious texts and documentary forms written in an indigenous Old Nubian script and the adoption of new royal regalia in preference to the older Byzantine styles. These changes are also reflected in the wall paintings of the churches across the region of Makuria, with the innovation of new art styles, and the invention of new motifs and forms of self-representation.7

Basics of Nubian wall painting

Paintings of royals figures are the most commonly attested among Nubian self-representations, followed by depictions of the church elite. However, many of the painted figures in Nubian art also included divine Christian figures such as the Trinity, angels and saints, and while many of these were initially based on Byzantine and Coptic models, they acquired a distinctly Nubian character based on the requirements of Nubian court ceremonies and their perception of the heavenly court8.

Depictions of the Trinity, the Archangels and the Nubian saint Anna are based on local religious traditions.9 But the initial use of Byzantine art styles may explain why saints continued to be depicted as “colorless” while the portraits of (living) Nubians and(non-Nubian) biblical figures were depicted with a dark-brown complexion10. For example, biblical figures such as the Magi (three wise men) and the shepherds from the nativity story, and other characters like Tobias are depicted as Nubians.11

Nubian art tended towards stylization and ornamentalism, in which images were essentially reduced to the attributes of the depicted archetype. Actual physical distinctions of individual figures weren't supposed to be portrayed as only general types were preferred. As a result, facial features and parts of the body are relatively 'synthetic', being based on specific models used by the different groups of artists from the same workshops.12

Detail of the 10th century nativity scene at Faras depicting the Magi on horseback

Detail of Nativity scenes from Kom H monastery at Old Dongola, showing the Magi (top left) and shepherds, photos by Małgorzata Martens-Czarnecka

Representing Royals in Nubian art: Protection scenes, Symbols of power and Regalia

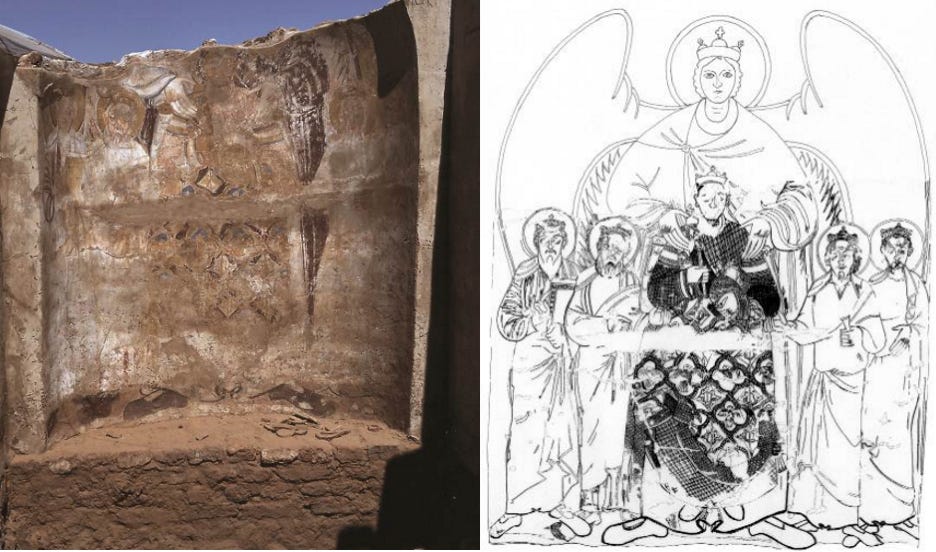

Among the most common paitings of royal figures in Nubian art were the ‘protection’ scenes, in which royals such as Kings, Queen Mothers, princes and princesses are depicted under the protection of holy figures. Although this type of representation had its precursors both in early Byzantine designs, it was greatly transformed in Nubia art where it became a particularly popular theme of murals from the ninth century up to the 14th century13. While portraying kings in the church interiors was relatively common in Byzantine art, representations of the ruler in the area of the sanctuary were extremely rare. On the other hand, the Nubian type of the official royal portrait in the apse of the Church represents a new innovation.14

Scenes depicting Nubian dignitaries protected by saints do not feature in the mural programs prior to the 9th-10th century when the oldest surviving examples of protection scenes of royals were found in the Cathedral of Faras and are first attested.15 These official representations mainly portray Nubian dignitaries under the protection of the Trinity, angels or saints, by depicting the latter standing behind or beside the royal, with their hands touching the shoulder of the royal. Such portraiture developed into an iconographic type that became popular in the wall decoration of Nubian Churches.16

14th century painting from Church NB.2.2 in Dongola depicting a Makurian king under the protection of Christ and two archangels, Michael and Raphael. photo by W. Godlewski

Portraits of King Georgios II and King Raphael, from the Church of Sonqi Tino, now at the Sudan National Museum.17

11th century paiting of a Nubian king under the holy patronage of an archangel, surrounded by Apostles. Chapel 3, Banganarti.18

14th century mural of a Nubian royal protected by Christ, from Faras Cathedral now in the National Museum in Warsaw

These protection scenes played an important role in the expression of royal ideology in the iconographic program of the churches. the Nubian ruler, who is depicted under the protection of the Archangel and/or the Apostles, becomes the main figure of the composition under heavenly protection.19 Such Portraits of individuals protected by divine figures can also be regarded also as private expressions of piety. In a symbolic way, the ruler transformed his mortal body into a visual representation. In consequence, the painting becomes not only a medium between image and viewer but also a perfect manifestation of the person’s individual existence as his eternal life in heaven.20

The kings are also depicted wearing the symbols of royal power in Makuria. These include the horned crown often surmounted by a cross on top, a scepter surmounted by a cross or a figure of Christ, and they are shown wearing rich robes that signify their authority. Makurian crowns are of diverse types and were based on a combination of Nubian and Byzantine styles, most of these crowns were worn by Kings but a few appear to have belonged to eparchs and other subordinate officials (although this distinction is still debated).21

12th century portrait of a King in Chapel 2 of Banganarti, the so called Eparch from Abd-el-Gadir Church, now at National Museum of Sudan, Khartoum.

The royal portraits also display another aspect of Nubian self-representation with regards to the clothes worn by the people of Nubia and the Makurian royal fashion. A comparative study of the royal costumes can be divided into two major groups: with early paintings often depicting kings dressed in clothes similar to Byzantine emperors whereas in later paitings, the kings' garments are worn in a Nubian fashion.22

The clothes worn by the 9th-10th century kings; Zacharias III and Georgios II are the most similar to Byzantine imperial attire. The king are depicted wearing a long dress tied with a belt and a cloak which covers his shoulders and left arm. But while Byzantine art differentiates the emperor from the other figures in the paiting using attributes like the crown and the richness of his clothing, In Nubian royal iconography, the costume, like the attributes, is worn only by the king.23

9th-10th century painting of King Zacharias III from Faras now at the Poland National Museum, and King Georgios II from Sonqi Tino, now at the Sudan National Museum.

However, beginning in the 11th-12th century, there was a noticeable evolution of the royal attire in Nubian royal portraits. The king's costume is still comprised of a combined dress and cloak attire, but arranged and styled differently. The kings' dress is often depicted with two sleeves on the wrist and arm, and the whole costume is decorated with geometric motifs. The cloaks are worn diagonally across the torso, folded on one shoulder with the cloak-tail being wrapped around the arm. The king also wears a second dress; in contrast to the portraits of the first group. It appears at the ankles under the “outer” dress, its edges are white, either straight or pleated.24

10th century painting of an unidentified king in the Nativity scene at Faras, now in the Sudan National Museum

12th century painting of King David, in the southern wall of Chapel 1 at Banganarti25

There are also a number of murals depicting high ranking royal figures, often standing alone. Some of these come from the church of Banganarti which was a pilgrimage site that included a sanctuary dedicated to the reigning King. The painting of an unamed royal/hegemon at Banganarti depicts him wearing a horned crown like the Nubian kings but holding a plain stick in the right hand instead of a sceptre.26 A few other paintings of royals come from the Church of Raphael in Old Dongola, where two royals are depicted, one of whom is named Abakuri.

11th century paiting of a Nubian dignitary ( hegemon ?) on the eastern wall of Room 20, Banganarti.

8th-9th century paintings, Representations of members of the royal court in the southeastern part of the naos of the Church of Raphael in Old Dongola.27

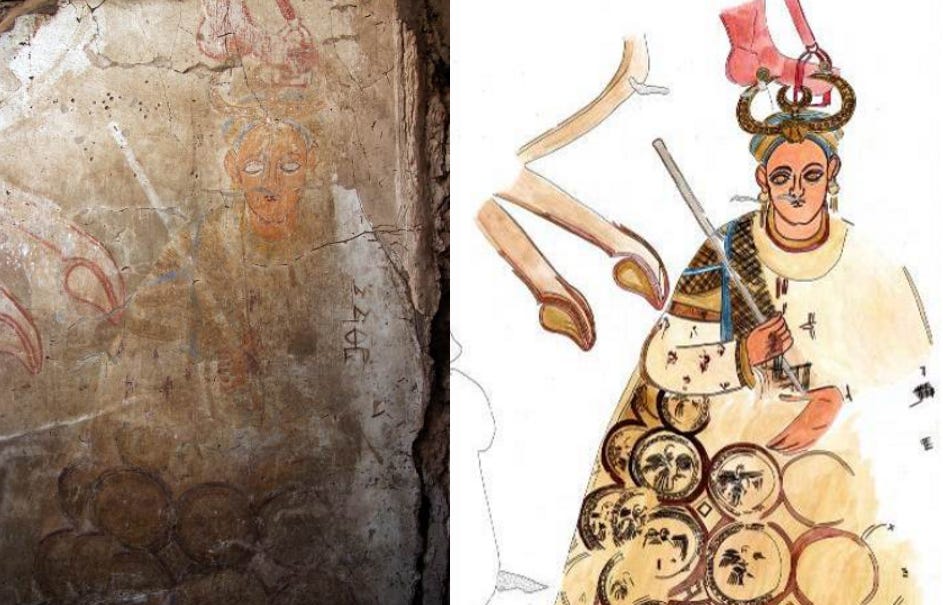

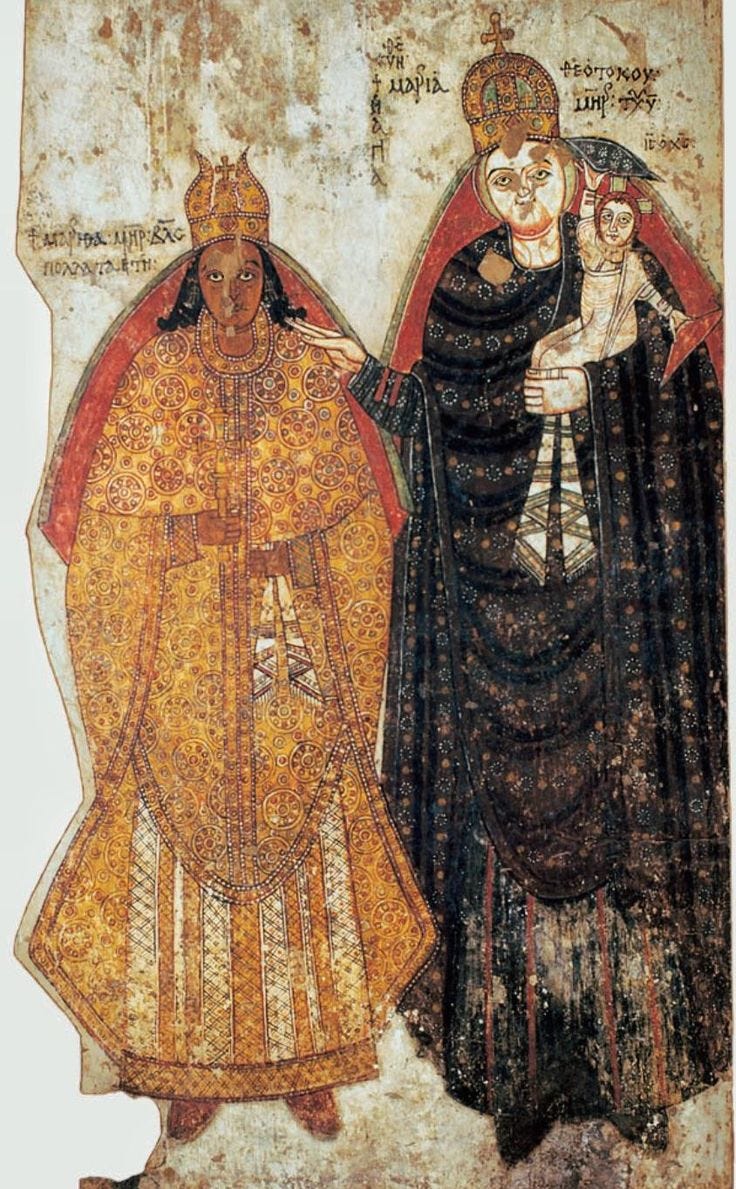

Besides the portraits of the male royals were depictions of prominent women in the Makurian royal court such as Queen mothers and princesses. In the northern nave of the Faras Cathedral, a group of paintings has been identified as representations of the mothers of the kings. This identification was based on the legend accompanying one of these representations, which describes a woman portrayed as a ‘Martha, Mother of the King’ and the similarities of the iconographic features of this painting with other female portraits across the kingdom. Like the depictions of kings, depictions of royal women in Nubian art are closely associated with the ecclesiastical paintings of Nubian female saints, the most prominent of whom was the Virgin Mary.28

11th century painting of The Queen mother (left) protected by the Virgin Mary and child (right) from the Petros Cathedral at Faras, Sudan National Museum

12th century painting of a Makurian princess under the protection of the virgin Mary, Faras cathedral

Depictions of Makurian women reveal more aspects of Nubian self-representation that reflect medieval Makuria’s social structure. The office of King Mother is well attested across the history of ancient and medieval Nubia including in the kingdom of Makuria. Nubian women enjoyed a relatively high social and economic status, they owned churches as patrons, they commissioned wall paintings, and owned property. Besides the office of the Queen Mother, an inscription from Faras also shows that some were deaconesses, making them prestigious members of the clerical staff of the Nubian church.29

Both the office and the representations of Queen Mothers in Nubian art have no equivalent in the Byzantine Empire nor in Coptic Egypt. Nubian depictions of royal women thus constitute a unique official iconographical program that depicted an unconventional ‘succession’ line: from Mary – mother of Christ, to the Mother of the King. By setting the image of the holy mothers and of the kings’ mothers beside each other, a parallel between the queen mother and the Virgin Mary is created: just as Mary was the mother of Christ, the Queen mother was the mother of a future Makurian ruler, Christ’s deputy on earth. It can thus be inferred from the special role of the king and his mother in the mural decoration of Nubian churches that this iconographical custom mirrored a specific social reality in Makuria.30

Representing Ecclesiastical figures in Nubian art

The institution of the Church in Makuria was closely associated with “secular” authority at the Royal court. Some of the most prominent Nubian Church leaders such as the 11th century Archbishop Georgios were of royal birth, other bishops such as Marianos had royal ambitions. Church officials in Makuria commissioned paintings, contributed to the construction of churches and monasteries, owned property and engaged in political and religious matters within the kingdom and with its foreign partners.31

Like the royals, the Nubia clergy were also represented under the protection of saints and holy figures, but were more often depicted alone. They are shown holding items that indicate their office such as headdresses with crosses, long staffs terminating in a cross, gospel books, and censers. These ecclesiastical garmets and symbols of authority were often adopted by the wider Eastern Christian world, with which Makuria closely interacted. For example, staffs were not common parts of the Makurian episcopal garments, as they don't appear in some of the paitings of bishops, the item was likely based on early representations of monastic saints in 6th century Egypt. Depictions of Books on the other hand, would have been based on gospel books that were commonly composed within Nubia itself.32

12th century painting of Bishop Georgios of Faras protected by the virgin Mary and Christ (upper left corner), Sudan National Museum, Khartoum

10th century painting of Bishop Petros protected by St. Peter the Apostle, from Faras Cathedral now in the National Museum in Warsaw

11th century painting of Bishop Marianos of Faras with virgin Mary and child, from Faras cathedral now at the national museum Warsaw

Members of the Nubian clergy were depicted in ecclesiastical vestments which represented local fashion traditions. Bishops and presbyters are shown wearing vestments that were commonly used by the liturgy of the Eastern Church and reflect the ecclesiastical influences of the eastern meditteranean. These influences led to the evolution of an original fashion style that characterized Makuria’s clerical society.33

All painted figures in Nubian art are clad in garments that indicate their position in the Nubian social hierarchy. Certain rules governed the choice of garmets for specific figures and the type of decoration featured on them. Some figures were portrayed with a wealth of imperial splendor (especially the Archangles and Royals), others are shown in religious vestments, while others were depicted in modest attire of monks and common subjects.34

11th century portrait of arch presbyter Marianos, from Old Dongola, Portrait of an unknown bishop from Old Dongola.

12th century painting of Georgios from Old Dongola, 9th century painting of a group of Nubian clergymen, National Museum in Warsaw

Representing subjects in Nubian art: A portrait of a cosmopolitan society

Representations of Nubian subjects are relatively few in the corpus of wall paintings of Makuria. The majority of Nubian murals described above were commisioned by donors including royals and clergy. These donors hired local artists (often monks from monasteries) to decorate the walls of churches and other buildings whose construction some of them had sponsored. They often appear in paintings as smaller figures of the larger figure which they commisioned, that is drawn beside them. While most of the donors were secular and religious elites, a few donors were drawn from the rest of the Makurian population.35

For example, the paintings below depict donors who were possibly clergymen, and are depicted wearing clothes that are slightly different from those worn by Bishops and royals. One of the donors is depicted holding a book in his left hand and a staff in his right hand rather than a scepter. Another donor is depicted standing with raised hands in a gesture of prayer, his clothing is similar to the garments worn by monks in both Nubia and Egypt.36

12th-13th century paintings of an archpresbyter depicted as a donor, and Two figures depicted as deacons, from Old Dongola, photos by Małgorzata Martens-Czarnecka

Conversely, there are also depictions of female donors in Southwest Annex of the Monastery on Kom H in Dongola. These women’s position in the church hierarchy is unclear, they could have been deaconesses such as the one recently discovered from an inscription at Faras,37 or were related to the royals and clergy depicted in church murals (either as wives or mothers). These female donors are often shown holding a distaff or a palm leaf. They wear voluminous robes that are richly decorated and their heads are often veiled.38

12th-13th century paintings of female donors from Southwest Annex, photos by Małgorzata Martens-Czarnecka

The Southwest Annex of the Monastery on Kom H in Dongola has a number of features that indicate a relation with womanhood. These include the many depictions of the Virgin Mary, the wall paitings donated by women, and the graffito which were written by women.39 One painting in particular depicts a dance scene whose accompanying inscriptions show that involves that its donor invokes the virgin Mary in the context of the Queen sister’s pregnancy.40

The painting includes two groups of men dancing next to an image of the Virgin Mary and child. The men constitute two types of figures in different attires, some have animal masks on their faces, the others are clad in sleeveless chitons and long galigaskins, skirts, shawls and turbans with bands. In the scene of dance, and the attires of men and their folk dance give evidence that the Nubian society was multicultural, reflecting its African roots and contemporary Islamic influences.41

12th-13th century painting of a dance scene from Old Dongola. Photos by Małgorzata Martens-Czarnecka

Representation of Nubian subjects in church murals was a product of the broader social changes and innovations in the kingdom of Makuria. As indicated by the painting above, the Nubian art styles of the post-11th century included less homogenous paiting themes, allowing greater freedom in selection of subjects, smaller sizes of portraits and different compositions of the representations. Its during this period that a few 'Islamic' influences begun to appear in Nubian art.42

Another exceptional painting depicting what appears to be Nubian subjects comes from the Southwestern Annex from Old Dongola. It depicts two men seated on the wide bed in the interior behind a folded curtain, behind the two men (or between them) is another standing figure (likely a servant). Below that composition, another servant skins a lamb, while more lambs are shown enclosed within a round fence. Above the main scene is another man seated on the semi-round sofa with his hand outstretched as if in a gesture of greeting towards an approaching couple, a man and woman clad in white robes.43

Like all Nubian paintings, this mural was inspired by biblical stories but depicted them in a contemporary Nubian setting. Local painters understood the purposes of the paintings that were being commissioned, often taken from Christian dogma as conveyed in the scriptures, as well as from the teachings of the Church fathers and from the Apocrypha.44

12th-13th century painting from Southwestern Annex from Old Dongola Monastery, photo by Małgorzata Martens-Czarnecka

Detail of the above painting showing a financial transaction between the two seated men, with one giving the other a handful of gold coins

Detail of the painting showing two figures (likely Tobias and Sara) being greeted by a seated figure (likely Raguel)

This mural is most likely based on the biblical story of Tobias in the ‘Book of Tobit’. In one of the episodes, Tobias travels with a friend named Azarias to claim payment for a debt owed to his father by a man named Gabael. Tobias recovers the debt, and he meets and marries Gabael's niece Sarah. Azarias turns out to be the archangel Raphael sent by God to answer the prayers of Sarah as well as Tobias’ father. The families of the newlyweds then celebrate with a sumptuous feast. The theological message of this story expressing God's care, the archangel's protection, the payment of debts and the marriage bond, likely inspired a donor to commission the painting.45

The depiction of the figures in the contemporary Nubian style and its influences reflects local forms of self-representation. The increasing Islamic influences as shown by the clothing which also appears in the abovementioned dance scene, were a prelude to the gradual Islamization of Nubian society. As the political and social life in the kingdom of Makuria became increasingly intertwined with Mamluk Egypt, Nubian society gradually lost its Christian character and took on a new Islamic character that is seen in modern Sudan.46

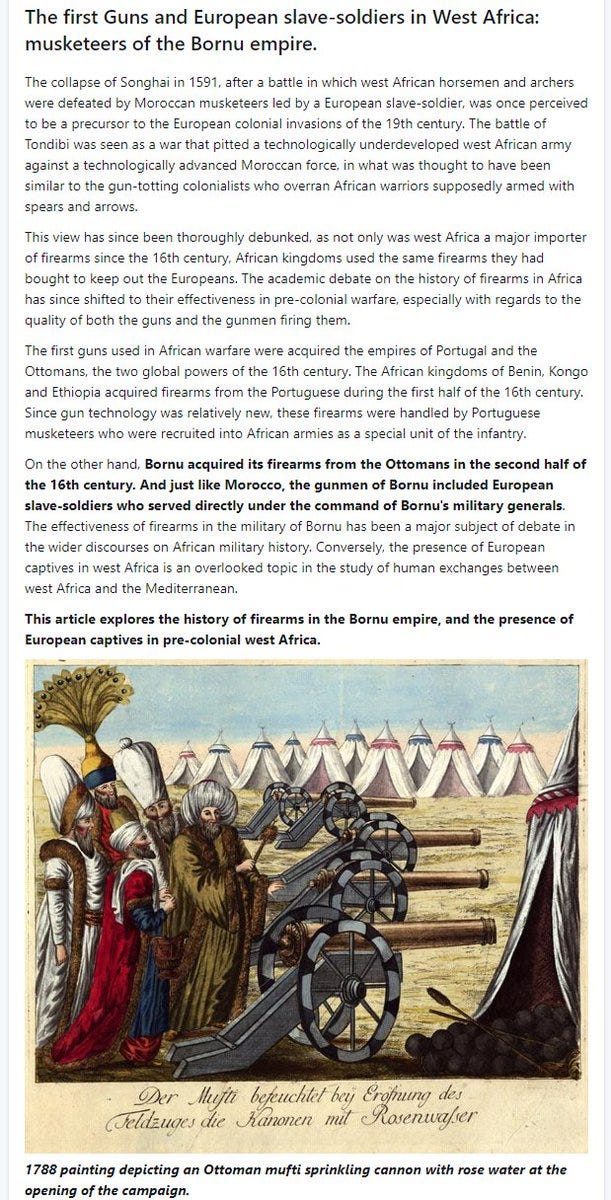

Beginning in the 1500s, African states acquired guns from the Ottomans and the Portuguese to create their own gun-powder empires. The west african empire of Bornu obtained guns and European slave-soldiers whom it used extensively in its campaigns. Read more about it here:

Études des peintures murales médiévales soudanaises de 1963 à nos jours by Magdalena M. Wozniak

The Wall Paintings from the Monastery on Kom H in Dongola by Małgorzata Martens-Czarnecka pg 108-109

Short history of the Church of Makuria by W Godlewski pg 599-601

The Oxford Handbook of Ancient Nubia by Bruce Williams pg 760)

The Oxford Handbook of Ancient Nubia by Bruce Williams pg pg 762-763)

Short history of the Church of Makuria by W Godlewski pg 602-609, Bishops and kings. The official program of the Pachoras (Faras) Cathedrals by W Godlewski pg 262-383

Archbishop georgios of dongola. socio-political change in the kingdom of makuria by W Godlewski pg 663-675

Byzantine influence on Nubian painting by Magdalena Łaptaś pg 252-253

The Holy Trinity in Nubian art by Piotr Makowski 302-307, Anna, the first Nubian saint known to us by Adam Łajtar, The position of the Archangel Michael within the celestial hierarchy by Magdalena Łaptaś

The Wall Paintings from the Monastery on Kom H in Dongola by Małgorzata Martens-Czarnecka pg 110

The Wall Paintings from the Monastery on Kom H in Dongola by Małgorzata Martens-Czarnecka pg 137-138

The Wall Paintings from the Monastery on Kom H in Dongola by Małgorzata Martens-Czarnecka pg pg 116)

Nubian Scenes of Protection from Faras as an Aid to Dating by Stefan Jakobielski pg 44)

The Iconography of Power – The Power of Iconography: The Nubian Royal Ideology and Its Expression in Wall Painting by Dobrochna Zielinska pg 946

The Iconography of Power – The Power of Iconography by Dobrochna Zielinska pg 943-944

Nubian Scenes of Protection from Faras as an Aid to Dating by Stefan Jakobielski pg 45-50, 943-944)

Royal iconography: contribution to the study of costume by Magdalena M Wozniak pg 930

Banganarti on the Nile, An Archaeological Guide by Bogdan Zurawski pg 32

The Iconography of Power – The Power of Iconography by Dobrochna Zielinska pg 944)

The Holy Trinity in Nubian art by Piotr Makowski pg 303)

The Crown of the Eparch of Nobadia by Magdalena Łaptaś, Horned Crown – an Epigraphic Evidence by Stefan Jakobielski

Royal Iconography: Contribution to the Study of Costume by Magdalena Wozniak pg 929-932)

Royal Iconography: Contribution to the Study of Costume by Magdalena Wozniak pg 933)

Royal Iconography: Contribution to the Study of Costume by Magdalena Wozniak pg 935

Banganarti on the Nile, An Archaeological Guide by Bogdan Zurawski pg 26-28

The chronology of the eastern chapels in the Upper Church at Banganarti, Banganarti on the Nile by Bogdan Zurawski pg 41

Dongola 2015-2016: Fieldwork, Conservation and Site Management pg 129

The Iconography of Power – The Power of Iconography by Dobrochna Zielinska p pg 947)

Female diaconate in medieval Nubia: Evidence from a wall inscription from Faras by Grzegorz Ochała pg 7-8)

The Iconography of Power – The Power of Iconography by Dobrochna Zielinska pg 947-948)

Short history of the Church of Makuria by W Godlewski pg 610-612

Monks and bishops in Old Dongola, and what their costumes can tell us by Karel C. Innemée pg 417-419

The Wall Paintings from the Monastery on Kom H in Dongola by Małgorzata Martens-Czarnecka pg 113)

The Wall Paintings from the Monastery on Kom H in Dongola by Małgorzata Martens-Czarnecka pg 112)

The Wall Paintings from the Monastery on Kom H in Dongola by Małgorzata Martens-Czarnecka pg 221-225

Monks and bishops in Old Dongola, and what their costumes can tell us by Karel C. Innemée pg 420-421)

Female diaconate in medieval Nubia: Evidence from a wall inscription from Faras by Grzegorz Ochała

The Wall Paintings from the Monastery on Kom H in Dongola by Małgorzata Martens-Czarnecka pg 224-225)

Women in the Southwest Annex by Van Gerven Oei Vincent W. J. and Łajtar Adam pg 75-76

A Dance for a Princess by Vincent van Gerven Oei pg 131-135

The Christian Nubia and the Arabs by Małgorzata Martens-Czarnecka pg 253-254

The Wall Paintings from the Monastery on Kom H in Dongola by Małgorzata Martens-Czarnecka pg 110

The Christian Nubia and the Arabs by Małgorzata Martens-Czarnecka pg 253

The Wall Paintings from the Monastery on Kom H in Dongola by Małgorzata Martens-Czarnecka pg 108-109

The Wall Paintings from the Monastery on Kom H in Dongola by Małgorzata Martens-Czarnecka pg 124-125)

The Christian Nubia and the Arabs by Małgorzata Martens-Czarnecka pg 253-255