State and society in southern Ethiopia: the Oromo kingdom of Jimma (ca. 1830-1932)

Modern Ethiopia is a diverse country comprised of many communities and languages, each with its history and contribution to the country's cultural heritage. While Ethiopian historiography is often focused on the historical developments in the northern regions of the country, some of the most significant events that shaped the emergence of the modern country during the 19th century occurred in its southern regions.

In a decisive break from the past, several monarchical states emerged among the Oromo-speaking societies in the Gibe region of southwestern Ethiopia, the most powerful of which was the kingdom of Jimma. Reputed to be one of the wealthiest regions in Ethiopia, the kingdom's political history traverses several key events in the country's history.

This article explores the history of the kingdom of Jimma from its emergence in 1830 to its end in 1932, reframing the complex story of modern Ethiopia from an Oromo perspective.

Map of Jimma in southwestern Ethiopia

Support African History Extra by becoming a member of our Patreon community, subscribe here to read more about African history, download free books, and keep this newsletter free for all:

Background on the political landscape of southern Ethiopia between the 16th and early 19th century.

Around the 16th century, the Gibe region of south-western Ethiopia was dominated by Oromo-speaking groups, who, through a protracted process of migration and military expansion, created diverse societies and political structures over some pre-existing societies such as the Sidama-speaking polities of Kaffa and Enarea. By the mid-18th century, increased competition for land, livestock, markets, and trade routes, between these Oromo societies led to the emergence of several states in the region.1

At the turn of the 19th century, there were at least five polities in the upper Gibe region that were known by contemporary visitors as the kingdoms of Limmu-Enarea; Gomma; Guma; Gera; and Jimma. The emergence of these kingdoms was influenced as much by internal processes in Oromo society; such as the emergence of successful military leaders, as it was by external influences; such as the revival of Red Sea trade and the expansion of trade routes into southern Ethiopia.2

Initially, the most powerful among these states was the kingdom of Limmu-Enarea founded by Bofo after a successful defense of the kingdom against an invasion by the kingdom of Guma. Limmu-Enarea reached its height during the reign of Bofu's son Ibsa Abba Bagibo (1825-61), a powerful monarch with a well-organized hierarchy of officials. Its main town of Sakka was an important commercial center on the trade route between Kaffa and the kingdoms of Shewa and Gojjam (part of the Ethiopian empire). It attracted Muslim merchants from the northern regions, who greatly influenced the adoption of Islam in the kingdom and its neighbors including the kingdom of Jimma.3

The polity of Jimma was established in the early 19th century by Abba Magal, a renowned Oromo warrior who expanded the kingdom from his center at Hirmata. By 1830, the kingdom of Jimma emerged as a powerful rival of Enarea, just as the latter was losing its northern frontier to the kingdom of Shewa. Jimma's king, Sanna Abba Jifar, had succeeded in uniting several smaller states under his control and conquered the important centers along the trade route linking Kaffa to the northern states of Gojjam and Shewa. In several clashes during the late 1830s and 1840s, Jimma defeated its neighbors on all sides, including Enarea. Abba Jifar transformed the kingdom from a congeries of small warring factions to a centralized state of growing economic and political power.4

Map of the Jimma kingdom in the late 19th century, showing the principal towns and settlements.5

The government in Jimma

Abba Jifar created many administrative and political innovations based on pre-existing institutions as well as external influences from Muslim traders. Innovations from the latter in particular were likely guided by the cleric and merchant named Abdul Hakim who settled near the king's palace at Jiren. However, traditional institutions co-existed with Islamic institutions, and the latter were only gradually adopted as more clerics settled in Jima during the late 19th century.6

Administration in Jimma was centralized and controlled by the king through a gradually developed bureaucracy.

The capital of Jimma was at Jiren where the palace compound of the King was established in the mid-19th century on a hill overlooking Hirmata, around which were hundreds of soldiers, servants and artisans.7 The building would later be reconstructed in 1870 by Abba Jifar II after a fire.8 Near the palace lived court officials, such as the prime minister, war minister, chief judge, scribes, court interpreters, lawyers, musicians, and other entertainers. There were stables, storehouses, treasuries, workshops, reception halls, houses for the royal family and visitors, servants, soldiers and a mosque.9

The kingdom was divided into sixty provinces, called k'oro, each under the jurisdiction of a governor, called an abba k'oro, whose province was further divided into five to ten districts (ganda), each under a district head known as the abba ganda. These governors supplied soldiers for the military and mobilized corvee labor for public works, but retained neither an army nor the right to collect taxes.10

Appointed officials staffed the administrative offices of Jimma, and none of the offices were hereditary save for the royal office itself. Officials such as tax collectors, judges, couriers, and military generals were drawn from several different categories including royals and non-royals, wealthy figures and men who distinguished themselves in war, as well as foreigners with special skills, including mercenaries, merchants, and Muslim teachers. These were supported directly by the king and through their private estates rather than by retaining a share of the taxes sent to the capital.11

Aba Jifar’s palace in the early 20th century, and today.

Expansion and consolidation of Jimma in the second half of the 19th century

Abba Jifar was succeeded by his son Abba Rebu in 1855 after the former's death. He led several campaigns against the neighboring kingdom of Gomma during his brief 4-year reign but was defeated by a coalition of forces from the kingdoms of Limmu, Gera, and Goma. His successor, Abba Bo'Ka (r. 1858-1864), also reigned for a relatively brief period during which Jimma society was Islamized, mosques were constructed near Jiren and land was granted to Muslim scholars. He also ordered his officials to build mosques in their respective provinces and to support local Sheikhs, making Jimma an important center of Islamic learning in southern Ethiopia.12

Abba Bo'ka was succeeded by Abba Gommol (r.1864-1878), under whose long reign the kingdom's borders were expanded eastwards to conquer the kingdom of Garo in 1875. The latter's rulers were integrated into Jimma society through intermarriage and appointment as officials at Jiren, and wealthy figures from Jimma settled in Garo. After he died in 1878, Gommol was succeeded by his 17-year-old son Abba Jifar II, who was soon confronted with the southward expansion of the kingdoms of; Gojjam under Takla Haymanot; and Shewa under Menelik II.13

mid-19th century manuscript of Sheikh Abdul Hakim, currently at the cleric’s mosque in Jimma.14

Late-19th-century manuscripts of Imam Sidiqiyo (d. 1892) at the Sadeka Mosque15

The old mosque of Afurtamaa (mosque of forty Ulama) was originally built as a timber structure by Abba Bo'ka, but was later reconstructed in stone by Abba Jifar II.16

Jimma during the reign of Abba Jifar II

At the time of Abba Jifar II's ascension, many who visited Jimma accorded him little hope of retaining his kingdom for long in the face of the expansionist armies of Shewa and Gojjam. But the shrewd king avoided openly confronting the armies of Gojjam, which were themselves defeated by the Shewa armies of Menelik in 1882. Abba Jifar then opted to placate Menelik's ambitions by paying annual tribute in cash and ivory, while Jimma's neighboring kingdoms would later become the target of Shewa's expansionist armies. Aside from a brief incident coinciding with Menelik’s enthronement as the Ethiopian emperor in 1889, Jimma remained firmly under the control of Abba Jifar II who would ultimately outlive his suzerain.17

During Abba Jifar II's long reign, trade flourished, agriculture and coffee growing expanded, and Jimma and its king gained a reputation for wealth and greatness. It is described by one visitor in 1901 as "almost the richest land of Abyssinia" and its capital Jiren was visited by 20-30,000 merchants where "all the products of southern Ethiopia are sold there, in many double rows of stalls about a third of a mile long.18 A later visitor in 1911 remarks that Abba Jafir was an intelligent ruler who “takes great pride in the prosperity of his country.” especially road-making19 Another visitor in 1920 observed that “Jimma owes its riches, not to any great natural superiority over the rest of the country, but to the liberal policy which encourages instead of cramping the industry of its inhabitants.”20

The markets of Jimma attracted long-distance caravans and were home to craft industries whose artisans furnished the palace and the army with their products. Hirmata, the trade center of Jimma's capital, was the greatest market of southwestern Ethiopia, attracting tens of thousands of people to it from all directions. Tolls were levied on caravans passing through the tollgates of the kingdom, while markets were under the control of a palace official.21

The basis of the domestic economy in Jimma, like in the neighboring states, was agro-pastoralism, concentrating on grains such as barley, sorghum, and maize, as well as raising cattle for the household economy. The main exports from Jimma to the regional markets included ivory and gold that were resupplied from the south, and coffee that was grown locally.22

While Coffee hardly featured in the agricultural products of Jimma in the 1850s23, it had become the dominant export by the late 19th century. In 1897, another visitor to Jimma observed "very extensive" farming of Coffee with "almost no fallow land", adding that the farmers produced "not only to meet local needs and pay taxes but also for export of bread [grain]" The economic prosperity of Jimma brought about by its better-managed coffee production relative to neighboring Ethiopian provinces attracted migrant farmers, and would later become a major source of conflict between the kingdom, its neighboring provincial governors, and its suzerains at Addis.24

High-class Oromo farmers in south-western Ethiopia, ca. 192025

section of the Jiren market in 1901, with baskets containing agricultural produce

The fall of Jimma in the early 20th century

In the later years, Abba Jifar's kingdom was surrounded on all sides by Ethiopian provinces directly administered by Menelik's appointees who intended to add Jimma to their provinces by taking advantage of Menelik's withdrawal from active government. Abba Jifar thus strengthened his army by purchasing more firearms and recruiting Ethiopian soldiers. The era of Menelik's successor Lij Iyasu (r. 1913-16) offered temporary respite. Still, relations became tense under Iyasu’s successor Empress Zewditu, as Haile Sellassie gradually took control of the government and eventually succeeded her in 1930. He then began centralizing control over the empire, especially its rich coffee-producing south.26

By 1930, the aging king retired from active rule and left the government in the hands of his grandson Abba Jobir, who was faced with a combination of increased demand of tribute to Addis, the appointment of an Imperial tax collector, and falling coffee prices. Abba Jobir’s attempts to assert his autonomy by directly confronting the Imperial armies were stalled when he was imprisoned by Haile Selassie and a rebellion broke out in Jimma that was only suppressed in 1832. After this rebellion, a governor was directly appointed over Jimma, ending the kingdom's autonomy.27

During the Italian occupation, Abba Jobir was freed and appointed sultan of the province of Galla-sidamo albeit without full autonomy. He was later re-imprisoned after the return of Haile Selassie who would later free him. By then, the kingdom of Jimma had been subsumed under the Ethiopian province of Kaffa, and is today part of the Oromia region.

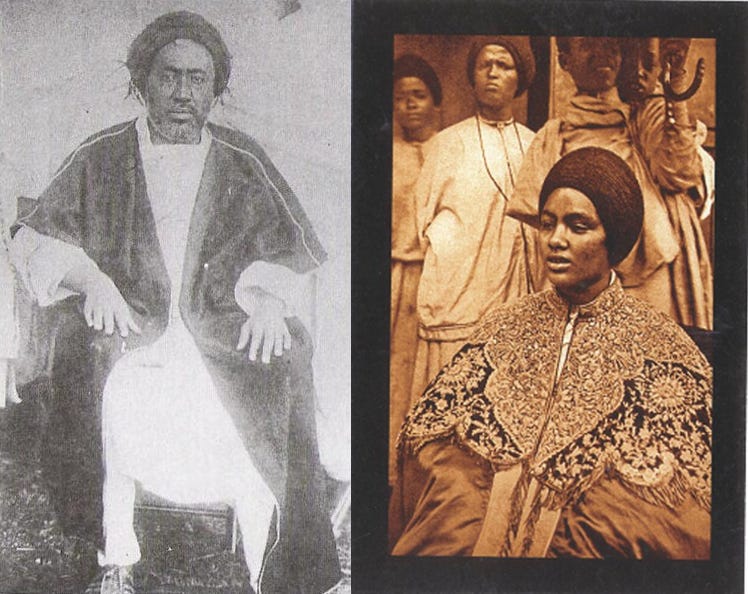

Portrait of Aba Jifar II, and his wife, early 20th-century photo

Many cultural developments along the East African coast are often thought to have been introduced by foreigners from southwestern Asia who migrated to the region, but recent research has revealed that East Africans regularly traveled to and settled in Arabia and the Persian Gulf where they established diasporic communities

Read more about this history of East African travel to Arabia here:

The Galla State of Jimma Abba Jifar by Herbert S. Lewis pg 323-322)

The Emergence and Consolidation of the Monarchies of Enarea and Jimma in the First Half of the Nineteenth Century by Mordechai Abir pg 206-208, The Islamization of the Gibe Region, Southwestern Ethiopia from c. 1830s to the Early Twentieth Century by G Gemeda pg 68-70)

The Cambridge History of Africa vol 5 pg 85, The Emergence and Consolidation of the Monarchies of Enarea and Jimma in the First Half of the Nineteenth Century by Mordechai Abir pg 208-210)

The Emergence and Consolidation of the Monarchies of Enarea and Jimma in the First Half of the Nineteenth Century by Mordechai Abir pg 217-218, Jimma Abba Jifar, an Oromo Monarchy: Ethiopia, 1830-1932 By Herbert S. Lewis pg 41 )

Map by Herbert S. Lewis

Jimma Abba Jifar, an Oromo Monarchy: Ethiopia, 1830-1932 By Herbert S. Lewis pg 41-42, The Islamization of the Gibe Region, Southwestern Ethiopia from c. 1830s to the Early Twentieth Century by G Gemeda pg 69-71)

The Journal of the Royal Geographical Society: JRGS, Volume 25 By Royal Geographical Society pg 212

Heritages and their conservation in the gibe region (Southwest Ethiopia): a history, ca. 1800-1980 by Nejib Raya pg 73-77

Jimma Abba Jifar, an Oromo Monarchy: Ethiopia, 1830-1932 By Herbert S. Lewis pg 68-76, The Galla State of Jimma Abba Jifar by Herbert S. Lewis pg 238)

The Galla State of Jimma Abba Jifar by Herbert S. Lewis pg 331-332)

The Galla State of Jimma Abba Jifar by Herbert S. Lewis pg 329-330)

Jimma Abba Jifar, an Oromo Monarchy: Ethiopia, 1830-1932 By Herbert S. Lewis pg 43, The Islamization of the Gibe Region, Southwestern Ethiopia from c. 1830s to the Early Twentieth Century by G Gemeda pg 72)

Jimma Abba Jifar, an Oromo Monarchy: Ethiopia, 1830-1932 By Herbert S. Lewis pg 43-44)

photo by Nejib Raya, reading: Heritages and their conservation in the gibe region (Southwest Ethiopia): a history, ca. 1800-1980

photo by Nejib Raya

Photo by ‘Jiren’ on Facebook, further reading: History of Islamic education in Jimma from 1830 to 2007 by Abdo Abazinab

The Rise of Coffee and the Demise of Colonial Autonomy by Guluma Gemeda pg 53-54, Jimma Abba Jifar, an Oromo Monarchy: Ethiopia, 1830-1932 By Herbert S. Lewis pg 45, Between the Jaws of Hyenas - A Diplomatic History of Ethiopia (1876-1896) By Richard Caulk pg 166

From the Somali Coast Through Southern Ethiopia to the Sudan By Oscar Neumann pg 390

A Journey in Southern Abyssinia by C. W. Gwynn, pg 133

Through South-Western Abyssinia to the Nile by L. F. I. Athill pg 355

The Galla State of Jimma Abba Jifar by Herbert S. Lewis pg 333-334)

The Galla State of Jimma Abba Jifar by Herbert S. Lewis 325-326)

On the Countries South of Abyssinia by CT Beke pg 260

The Rise of Coffee and the Demise of Colonial Autonomy: The Oromo Kingdom of Jimma and Political Centralization in Ethiopia by Guluma Gemeda pg 60-61)

Photo by L. F. I. Athill

The Rise of Coffee and the Demise of Colonial Autonomy: The Oromo Kingdom of Jimma and Political Centralization in Ethiopia by Guluma Gemeda pg 55-57)

The Rise of Coffee and the Demise of Colonial Autonomy: The Oromo Kingdom of Jimma and Political Centralization in Ethiopia by Guluma Gemeda pg 62-66)

I love your essays. Thank you for these insightful posts on African history.