State archives and scribal practices in central Africa: A literary history of Kahenda (1677-1926)

Exercising and negotiating power through writing.

In 1934, one of the most remarkable collections of African literature was opened to the public; a cache of several hundred documents spanning from 1677 to 1926 was taken from the state archive of Kahenda, a small polity in the Dembos region of modern Angola. This carefully preserved corpus was the first of many state archives and thousands of manuscripts that have been found in the region, it contained everything from matters of politics and diplomacy, to lineage history and land sales, all of which was written by local scribes and represented a well-developed documentary practice in west-central Africa.1

The adoption of writing and establishment of a scribal tradition in the state of Kahenda and by other aristocracies in the Dembos marked a decisive change in the negotiation and exercise of political power in a contested frontier zone that was sandwiched between the regional powers of west-central Africa and the colonial enclaves of the Atlantic world.

This article provides an overview of the scribal traditions of Kahenda, and decisive role of writing in the political history of west-central Africa.

Map of West-Central Africa in the mid 17th century showing the Dembos region (green) between the kingdom of Kongo (blue) and the colony of Portuguese-Angola

Support African History Extra by becoming a member of our Patreon community, subscribe here to read more about African history, download free books, and keep this newsletter free for all:

A brief history of the Dembos: from Mbwila to Kahenda (16th-17th century)

The "Dembos" was a region at the southern frontier of the kingdom of Kongo, that was characterized by a rugged terrain which made it easily defensible and difficult for the regional powers to conquer. The Dembo's societies constituted of small, clustered polities predominately settled by Kimbundu speakers, and often loosely united into federations under the leadership of rulers (sobas) who often bore the title "Ndembo", and were nominally loyal to the greater powers of the region; often Kongo, and later; Portuguese-Angola and Matamba2

The names of the polities in the Dembos regions were; "Caculo Cacahenda" (Kahenda), Cazuangongo, Quibaxi Quiamubemba, etc, and the titles of their rules often carried the name of the territory; eg dembo Kahenda, dembo Cazuangongo, etc, with the title being passed on to whoever succeeded to the throne of a given dembo in the same way that the Manikongo title was passed on for the whoever occupied the position of 'king of Kongo'.3

Prior to the gradual expansion of the colony of Portuguese-Angola, the Dembos region was under the vassalage of the kingdom of Kongo, and was repeatedly contested by Kongo and Angola in the early 17th century, as the smaller Dembos polities leveraged their alliances with stronger neighbors to maintain their independence. The strongest of them was Mbwila which had been in Kongo's orbit before it signed treaties with Portuguese-Angola in 1619, but then revoked them to re-sign treaties with Kongo's Pedro II in 1622 (prior to his victory against Portuguese-Angola in 1663). Mbwila later fell under the political orbit of Queen Njinga's Matamba kingdom during the 1640s, but later returned to Kongo briefly, before it was retaken by Portuguese-Angola (after the latter's victory in the war against Kongo in 1665).4

After Portugal's defeat by the armies of Kongo's province of Soyo in 1670, Mbwila remained effectively autonomous as soon as the Portuguese armies left, but its dominance over the other Dembos polities was declining relative to Kahenda, which was challenging the power of Mbwila used Angola's support to take over the another polity named Mutemo a Kinjenga in 1686. Kahenda's ascendance was checked by Matamba's Queen Verónica Kandala, who in 1688 sent her armies in the Dembos to recover her kingdom's lost territories and was received by the dembo Mbwila, but by 1692, her overextended armies were forced to withdraw from the Dembos region after the Portuguese attacked Mbwila but couldn't annex it.5

The dembo Kahenda thus leaned closer into the political sphere of Portuguese-Angola as a nominal vassal, signing vassalage treaties (just like Mbwila) in exchange for military alliance against larger states such as Matamba and payment of tribute, but retained near-complete autonomy over Kahenda's politics and commerce. These vassalage contracts established a relationship of unilateral dependence between both parties, and this relationship was not engendered through violence, but through negotiations, appropriations, recognition and legitimation.6

The history of Kahenda: government, trade and foreign relations

The small state of Kahenda was structured much in the same way as the better known kingdom of Kongo but with less elaborate institutions. The dembo Kahenda was elected by macotas (a state council comprised of lineage heads, some with the title "mane"), with collaboration by muenes (powerful royal women) and he governed from a banza (capital/town). He was assisted by an administration that included subordinate chiefs (sobas), and secretaries, the latter of whom were initially drawn from foreign trading class, but was later displaced by locally-born scribes. If deposed, the formerly reigning dembo Kahenda would be retained as an "honorary dembo" serving as an advisor to the succeeding administration.7

Letter from (honorary dembo) D. Sebastiao Francisco Cheque, sent to the (reigning) dembo Kahenda D. Francisco Afonso Da Silva, on 17th October 1794, about the activities of a ‘Muene’ Zangui (Arquivo Histórico Ultramarino, PT/AHU/DEMBOS/0000028)

Kahenda had a largely rural and agricultural economy, but some of its population was also engaged in production of both cotton and raffia textiles (which served also currency and was collected as tribute or redistributed to loyal sobas), as well as other forms of craft industries and trading.9 The Dembos region, on top of being part of the regional trade in textiles, ivory, salt and other commodities, was one of the conduits for the slave trade terminating at Luanda. While the bulk of the slave traffic came from outside the region and peace was more preferable for conducting trade than war (taxes on traders were a less costly source of revenue than war/"raiding"), the fractious nature of the small states ensured a steady supply as a secondary effect of local wars10. Conflicts in the Dembos were a attimes (albeit very rarely) moderated by the intervention of Angolan authorities eg stopping a civil war in Kahenda during 1768/1772, and exiling a local secretary in 1785 at the request of the macota councilors who had accused the secretary of conspiring to depose the reigning dembo Kahenda Sebastião Francisco Cheque (author of the above letter) .11

Letter from a soba named Pedro Damiao Da Silva, sent to the dembo Kahenda Francisco João Sebastião Cheque, on 28th september, 1865, that includes a request for textiles (Arquivo Histórico Ultramarino, PT/AHU/DEMBOS/00002512)

The adoption and evolution of writing in Kahenda: from signing treaties to establishing state archives

The political setting in Kahenda was therefore largely dominated by the contest between the central African powers and the colonial authorities at Angola. It was in this contested space that Kahenda negotiated its autonomy by alternating and overlapping its treaties of vassalage between Kongo and Portuguese-Angola, the former of whose king was considered the founding father of Kahenda (the Dembos inhabitants often called themselves "sons of Kongo"). The vassalage and connection to Kongo, however superficial, legitimated the authority of the dembo, and in exchange for the Kongo kings granting them royal insignia, some of the states in the Dembos region occasionally sent tribute to Kongo well into the late 19th century.13 For the dembo Kahenda, acts of vassalage were valid only as long as they did not threaten his political autonomy, when they did, he would alternate his allegiance depending on whose authority was more distant and less threatening.14"The Dembos area was connected to Angola through vassalage agreements which were frequently ignored, and Portugal’s coercive power was limited"15

Kahenda's act of vassalage to both Angola and Kongo, however nominal, was nevertheless the beginning of a complex chain of political and diplomatic relations, in which writing played a central role. Like in Kongo, the initial establishment of a scribal tradition in Kahenda was associated with political authority (and a syncretic culture that included the superficial adoption of some Iberian titulature), but unlike in the fully independent Kongo where this initial spread of writing was done fully under its authority (notably by king Afonso I), Kahenda's scribal tradition begun with the signing of treaties of vassalage; which served as proof of Kahenda’s relationship with its suzerains (Portuguse-Angola and later Kongo). Written agreements enabled the dembo Kahenda to legitimate his own power, and were an avenue for diplomatic procedure, especially in the use of written correspondence with Angola and Kongo, but also internally within Kahenda and its peers in the Dembos region.16

Declarations made by various dembo Kahendas about the payment of "tithe" (taxes) in 1822, 1850, 1852, addressed to the authorities at Angola (Arquivo Histórico Ultramarino, PT/AHU/DEMBOS/001440, PT/AHU/DEMBOS/001452, PT/AHU/DEMBOS/001419)

But the scribal traditions of Kahenda quickly transcended their initial use in treaty-making, and just as the foreign secretaries were displaced by locally-educated ones, the use of writing became an intellectual instrument that strengthened the bureaucratic organization of power in Kahenda, especially in its correspondence with the ruling classes of the Dembos region (dembo of Mufuque Aquitupa17). Written correspondence included political issues such as; the election of new Ndembu, dispatch of ambassadors, matters of succession, Religious matters between the itinerant clerical orders and the Kahenda elites, and issues of trade such as land sales, and gift-giving between the dembo Kahenda, merchants and subordinate chiefs (such as the dembo Cabonda Cahui18

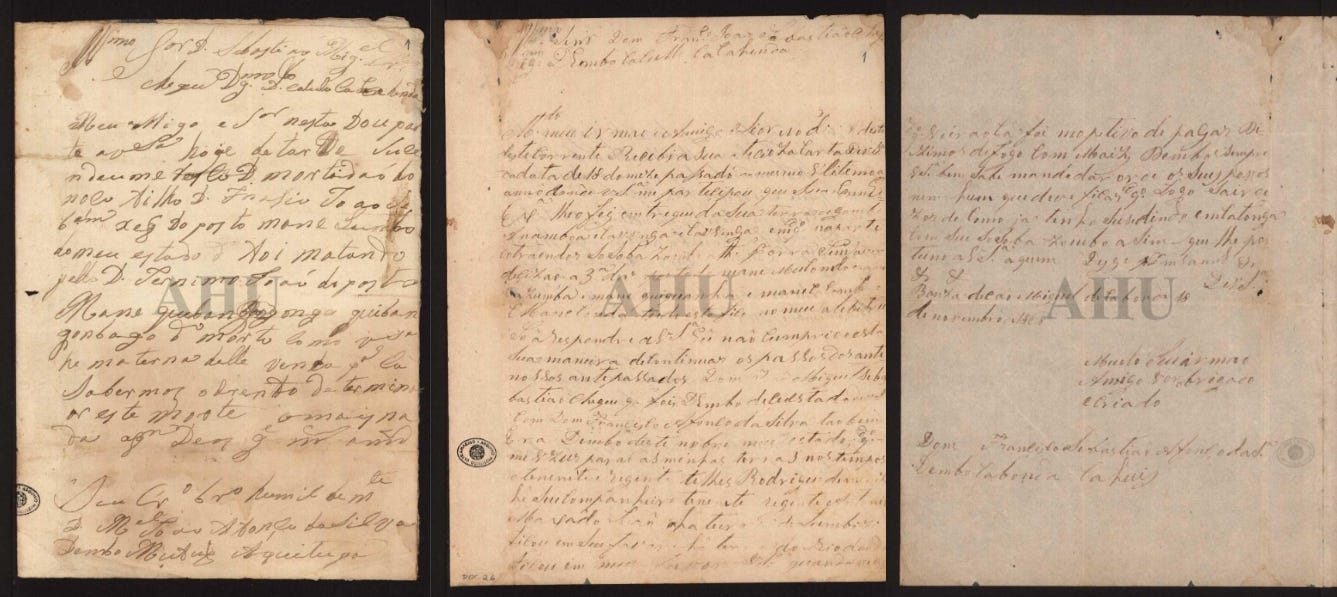

(1) Letter by the dembo of Mufuque Aquitupa named D. Miguel Vieira Afonso da Silva to the dembo Kahenda named Miguel Francisco, dated 28th, September 1865, in reply to a letter from the latter to the former, dated 24th September 1865. Discussing issues of patrilineal and matrilineal succession in the chiefdom of 'Mufuque Aquitupa' (Arquivo Histórico Ultramarino, PT/AHU/DEMBOS/00002419) (2-3) Letter by the dembo of Cabonda Cahui named D. Francisco Afonso da Silva to the dembo of Kahenda named D. João Miguel Sebastião Cheque, dated 11th November, 1868, About the former's gratitude for receiving land (Arquivo Histórico Ultramarino, PT/AHU/DEMBOS/00002620)

Various letters written in 1853, 1855, 1868, 1856, dealing with land sales, requests for gunpowder, matters about confession and baptism in the Dembos (Arquivo Histórico Ultramarino, PT/AHU/DEMBOS/000191, PT/AHU/DEMBOS/000180, PT/AHU/DEMBOS/000094, PT/AHU/DEMBOS/000042)

The elites of Kahenda and their peers in the Dembos region, set up state archives, referred to as trastesalio - a word independent of both the Kimbundu and Portuguese languages but coined by the Dembos archivists to refer to "things of the state"21. The establishment of state archives was a consequence of the creation of bureaucratic structures based on registers and written correspondence in which the state secretaries (or scribes), the dembo Kahenda, and the councilors (macotas) played a key role both as the writers of the documents in those archives but also as the custodians of the state's official correspondence. The secretaries in particular also served as teachers for the children of the elite in an individualized system of education.22

Imported Paper was acquired through diplomatic gifts and trade, and it arrived alongside other goods that included writing materials (ink and quills), Royal documents often contained seals marked with the royal arms of the senders as well as stamps and red waxes, the language of writing was both Portuguese and Kimbundu, often with annotations in the latter. The formalization of Kahenda's scribal tradition (and in the rest of the Dembos) was such that one observer remarked that; "there is no dembo chief who does not have wax, seal and scribe".23

Letter from D. Domingos António da Silva sent to the dembo Kahenda D. Francisco João Sebastião Cheque, in 1865. it includes a request for ink. (Arquivo Histórico Ultramarino, PT/AHU/DEMBOS/00002224)

Letters addressed to various dembo Kahendas, from 1863, 1878, 1870, responding to requests for paper to use in Kahendo, (Arquivo Histórico Ultramarino, PT/AHU/DEMBOS/000039, PT/AHU/DEMBOS/000088, PT/AHU/DEMBOS/000089)

Kahenda in the 19th and early 20th centuries.

By the mid-19th century, the reigning dembo Kahenda; (named Francisco João Sebastião Cheque) had refused to fulfill any of the clauses of his vassalage (such as the payment of tribute, return of fugitives and protection of Portuguese traders), and while this refusal had repeatedly occurred in the past as Kahenda was only nominally under Portuguese authority (which was barely exercised outside the occasional receiving of “tithe”), it came at a time when the Portuguese authorities were increasingly asserting their claims of authority to ward off the threat from other European imperial powers (read about; the “rose-coloured map").

The dembo Kahenda repeatedly asserted his autonomy from Portuguese-Angola by claiming vassalage to Kongo's king Pedro V (r. 1851-1891), using written correspondence between himself and the latter as proof, and forcing the Portuguese to communicate through Pedro as a mediator.25 The state of Kahenda had also become a refuge for runaway slaves and fugitives from Portuguese-Angola whom the dembo Kahenda refused to hand over, and when a Portuguese column was sent to pacify it in 1872, its soldiers deserted and were settled in Kahenda. A second Portuguese column under Colonel Gomes de Almeida was later sent to finish the failed mission of the first, but the Portuguese resolved to sign a peace treaty with the dembo Kahenda, and this uneasy peace was maintained with regular correspondence until 1907-1909 when two more campaigns failed to pacify the region. The dembo Kahenda only agreed to become a nominal vassal of Portuguese-Angola in 1910, after being recognized as a vassal of Kongo, and wasn't until 1918 (4 years after the Portuguese annexation of Kongo) that Kahenda was formally brought under the colony of Angola.26

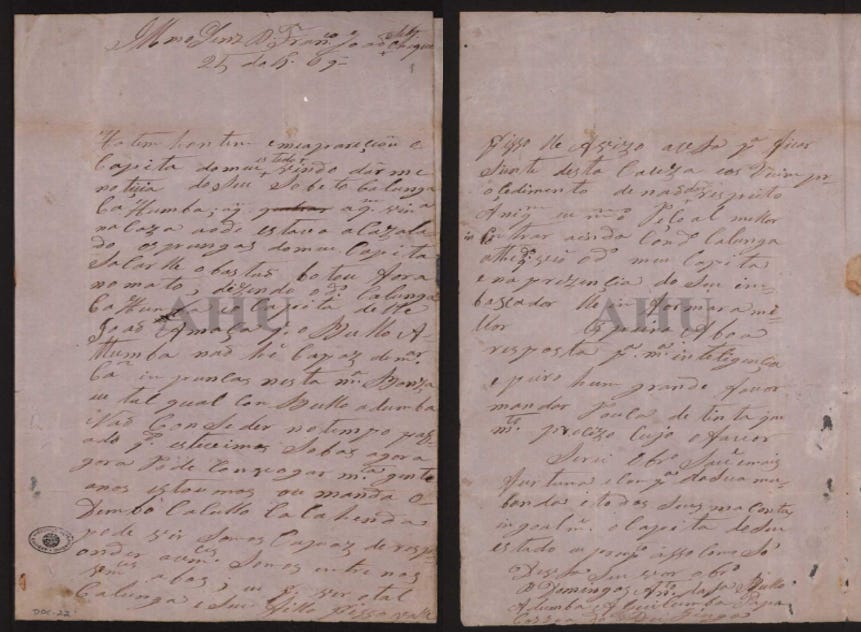

Three letters written between 1868-1869 written by dembos allied to Portuguese-Angola, on conflicts about vassalage in the region, the king of Kongo, and tobacco trade (Arquivo Histórico Ultramarino, PT/AHU/DEMBOS/000805, PT/AHU/DEMBOS/000807, PT/AHU/DEMBOS/000823)

(1) letter from Colonel Gomes de Almeida to D. Francisco João Sebastião Cheque , written in September 1872, about the latter's delay in signing the peace agreement. (2) One of the last letters addressed to a dembo Kahenda, written in March 1907 (Arquivo Histórico Ultramarino PT/AHU/DEMBOS/000858, PT/AHU/DEMBOS/001023)

After their careful storage for nearly three centuries, the elites of the former dembo Kahenda gave*27 some of their documents in their state archives to the anthropologist António de Almeida in 1934. This was the first of many similar archives from the Dembos that were opened for study in the Dembos region, including the archives of; Dembo Mufuque Aquitupa, Dembo Ndala Cabassa and Dembo Pango Aluquem, all of which ultimately numbered several thousand documents, the vast majority of which cover internal political and social relations and are an invaluable source of African history.28

Conclusion: Kahenda's scribal traditions and the Ndembu Archives in African history

The scribal traditions of the Dembos region are a testament to the diversity in the use of writing in Africa. Due to the mostly political nature of its adoption, the use of writing in Kahenda was not intended to recount legendary epics but instead represents a very formalized description of a west central African society, from which one is able to identify real actors, who convey information only intended for immediate utility.

The importance Ndembu state archives to the historiography of west-central Africa challenges the way in which African history is written, and is yet another example of Africa as a continent whose writing traditions have not been studied.

royal seal of the dembo Kahenda, 1836

During the 17th century, the East African coast was the site of a major intellectual revolution, with the writing of works on Philosophy, Poetry and History,

Read about the history of Swahili literature on my Patreon

Africæ monumenta: Arquivo Caculo Cacahenda by Ana Paula Tavares, Catarina Madeira Santos

A History of West Central Africa to 1850 by John Thornton pg 23, 102)

O dembo caculo cacahenda by Daiana Lucas Vieira pg 13

A History of West Central Africa to 1850 by John Thornton 114, 135 , 163, 182)

A History of West Central Africa to 1850 by John Thornton pg 209-210)

“Sempre Vassalo Fiel de Sua Majestade Fidelíssima” by Ariane Carvalho da Cruz pg 69)

Les archives ndembu (XVIIe -XXe siècles) by Catarina Madeira Santos pg 780-781)

link to the letter in the collection at Arquivo Histórico Ultramarino (for the other letters, simple go to “simple search” at the top of the same page and type in the reference number that i have provided)

O dembo caculo cacahenda by Daiana Lucas Vieira pg 38)

A History of West Central Africa to 1850 by John Thornton pg 294-295

Les archives ndembu (XVIIe -XXe siècles) by Catarina Madeira Santos pg 781)

Les archives ndembu (XVIIe -XXe siècles) by Catarina Madeira Santos pg 792-793, Kongo in the Age of Empire, 1860–1913 by Jelmer Vos pg 38)

O dembo caculo cacahenda by Daiana Lucas Vieira pg 79)

A History of West Central Africa to 1850 by John Thornton pg 251-252

Les archives ndembu (XVIIe -XXe siècles) by Catarina Madeira Santos pg 775-779)

Les archives ndembu (XVIIe -XXe siècles) by Catarina Madeira Santos pg 794

Africæ monumenta: Arquivo Caculo Cacahenda by Ana Paula Tavares, Catarina Madeira Santos pg 422

Les archives ndembu (XVIIe -XXe siècles) by Catarina Madeira Santos pg 794

Les archives ndembu (XVIIe -XXe siècles) by Catarina Madeira Santos pg 780, 783)

Les archives ndembu (XVIIe -XXe siècles) by Catarina Madeira Santos pg 773-774, 788)

O dembo caculo cacahenda by Daiana Lucas Vieira pg 79, Kongo in the Age of Empire, 1860–1913 by Jelmer Vos pg 38

O dembo caculo cacahenda by Daiana Lucas Vieira pg 94-106)

* the exact circumstances in which António de Almeida found and took the first batch of documents from the “caculo cacahenda archive” weren’t ethical, and most remained inaccessible to scholars until fairly recently

Les archives ndembu (XVIIe -XXe siècles) by Catarina Madeira Santos pg 771-772)

A fascinating read! Thank you for the writeup.