State building in ancient west Africa: from the Tichitt neolithic civilization to the empire of Ghana (2,200BC-1250AD)

A "cradle" of west african civilization

The Tichitt neolithic civilization and the Ghana empire which emerged from it remain one of the most enigmatic but pivotal chapters in African history. This ancient appearance of a complex society in the 3rd millennium BC west Africa that was contemporaneous with Old-kingdom Egypt, Early-dynastic Mesopotamia and the ancient Indus valley civilization, overturned many of the diffusionist theories that attributed the founding of west African civilizations to ancient Semitic immigrants from Carthage and the near east1, The emergence of the empire of Ghana from the ruins of the tichitt tradition in 300 AD, whose political reach covered vast swathes of west Africa, and whose commercial influence was felt as far as spain (Andalusia), opened an overlooked window into west Africa's past, in particular, the complex processes of statecraft that led to the emergence of vast empires in the region.

Recent studies of the Tichitt neolithic tradition, the Ghana empire, and early west African history in general have proven that the cities, trade connections and manufactures of west Africa were bigger, more sophisticated, and more expansive than previously thought, and that they appeared much earlier than previously imagined. These studies also provide us with an understanding of the novel ways in which early west African states organized themselves; with large states structured as confederations of semi-autonomous polities that paid tribute to the center and recognized its ruler as their suzerain, and with the suzerain maintaining a mobile royal capital that moved through the subordinate provinces, while retaining ritual primacy over his kinglets2. This distinctive form of state-craft was first attested in the Ghana empire and later transmitted to the Mali empire and its successor states in west Africa.

This article explorers the advent of social complexity in west Africa from the little-known Tichitt neolithic to the emergence of the Ghana empire.

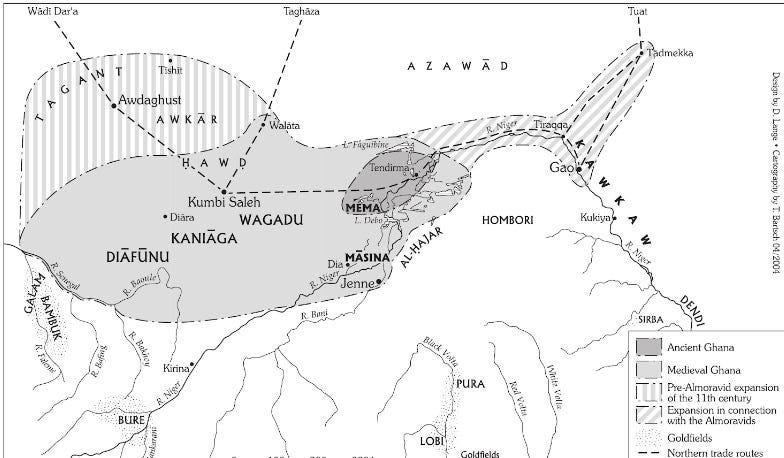

Map of the empire of Ghana at its height in the 12th century

Support African History Extra by becoming a member of our Patreon community, subscribe here to read more about African history, download free books, and keep this newsletter free for all:

A “cradle” of west African civilization: the Tichitt neolithic tradition of southern Mauritania

Map of the tichitt neolithic sites of the 2nd millenium BC and the Inland Niger delta sites of the 1st millenium BC.

The Tichitt neolithic tradition is arguably West Africa’s first large-scale complex society, the 200,000 km2 polity was centered in the dhar tichitt and dhar walata escarpments and extended over the dhar tagant and dhar nema regions in what is now south-eastern Mauritania. The area was permanently settled by agro pastoral communities after 2200-1900BC following a period of semi-permanent settlement that begun around 2600BC. These agro-pastoral groups, who were identified as proto-Soninke speakers of the Mandé language family, lived in dry-stone masonry structures built within aggregated compounds, they raised cattle, sheep and goats, cultivated pearl millet and smelted iron. Cereal agriculture in the form of domesticated pearl millet was extant from the very advent of the Tichitt tradition with the earliest dates coming from the early tichitt phase (2200/1900-1600BC) indicating that the tichitt agriculturalists had already domesticated pearl millet before arriving in the region thus pushing the beginnings of cultivation back to the pre-tichitt phase (2600-2200/1900BC) and were part of a much wider multi-centric process of domestication which was sweeping the Sahel at the time with similar evidence for domesticated pearl millet in the 3rd millennium BC from mali’s tilemsi valley and the bandiagara region, as well as in northern Ghana.3 The classic tichitt phase (1600BC-1000BC) witnessed a socioeconomic transformation during which most of Tichitt’s main population centers developed, with the greatest amount of dry-stone construction across all sites including a clearly defined settlement hierarchy in which the smallest settlement unit was a "compound" enclosed in a high wall (now only 2m tall) containing several housing units occupied by atleast 14 dwellers, the polity was arranged in a settlement hierarchy of four ranks, which included; 72 hamlets with 20 compounds each, 12 villages with 50 compounds each, 5 large villages with 198 compounds each, and a large proto-urban center called Dakhlet el Atrouss-I containing 540 stone-walled compounds with an elite necropolis whose tumuli graves are surmounted by stone pillars and were associated with religious activity. Dakhlet el atrouss housed just under 10,000 inhabitants4, and may be considered west Africa's earliest proto-urban settlement and one of the continents oldest. The size and extent of the tichitt neolithic settlements of this period exceeds many of the medieval urban sites associated with the empires of Ghana and Mali and this phase of the tichitt tradition has been referred to as an incipient state or a complex chiefdom.5 the disproportionately large number of monumental tombs in the vicinity of dhar Tichitt especially at Dakhlet el atrouss attests to an ancient ideological center of gravity and a sense of the sacred attached to dhar Tichitt over the '“districts” of dhar tagant, walata and nema and its status as an ancestral locality may have made it an indispensable dwelling place for elites.6 There's plenty of evidence for iron working in the late phase tichitt sites (1000-400/200BC) including slag and furnaces from the early first millennium at the sites of dhar nema and dhar tagant dated to between 800-400BC, which is contemporaneous with the earliest evidence of iron metallurgy throughout west Africa and central Africa.7 dhar mema also appears to have been the last of the tichitt sites to be settled as the tichitt populations progressively moved south into the ‘inland Niger delta’ region to establish what are now knows as the "Faïta sites" (1300-200 BC), as evidenced by the appearance of classic tichitt pottery, and similar material culture in settlements such as Dia where tichitt ceramics appear in the earliest phases between 800 400BC.8

the Akreijit regional center in the dhar tichitt ruins, the perimeter wall is 2m high and encloses dozens of compounds the smallest measuring 75 m2 and the largest measuring 2,394 m29

The collapse of the tichitt traditions is still subject to debate, the region appears to have been gradually abandoned from the middle of the first millennium BC onwards, most likely due to the onset of arid climatic conditions during the so-called “Big Dry” period from 300 BCE to 300 CE, as well as an influx of proto-Berber groups from the central Sahara desert. Some archeologists suggested that there was a violent encounter with the Tichitt polity and these proto-Berber migrations into the region that caused its eventual abandonment, based on evidence from nearby rock art that included depictions of ox-carts, horse-riders and battle scenes10 (although these can’t be accurately dated), recent studies suggest a cultural syncretism between the proto-soninke inhabitants of tichitt and the berber incomers with evidence of a slight increase in population rather than a precipitous decline at dhar nema11, while other studies downplay the syncretism observing the tendency of the proto-berber groups to opportunistically use earlier settlements’ features without initiating a building style of their own, and the distribution of some of their rock-art on the periphery of the tichitt tradition as indicators that they were for the most part, not inhabiting the Tichitt drystone masonry settlements.12 the last observation of which is supported by recent studies of the tichitt rock art that suggest that there were two rock art traditions made by both the incoming proto-berber groups and the autochthonous proto-soninke groups depicting the same events that included mounted housemen and possibly battle scenes.13

“Main panel” of the painted figures on cave wall at Guilemsi, Tagant, Mauritania, 200 km west of the renowned neolithic sites at dhar Tichitt. its observed to stylistically different from the proto-berber horse paintings and was most likely painted by the soninke depicting a battle scene fought with the former on the right.14

The Tichitt neolithic civilization, traverses many key frontiers in the archaeology of West Africa that include; the beginnings of cereal agriculture, early complex societies, the advent of complex architectural forms, the start of west african urbanism and the origins of iron metallurgy. More importantly, the tichitt tradition accomplishes what some contemporaneous African neolithic iron-age traditions failed to attain, that is; the direct transition into a state-level society (kingdoms and empires). The Nok neolithic tradition (1500-1BC)15 of central Nigeria, the Urewe neolithic (800/500BC-500AD)16 in central africa and the (pre-iron age) Kintampo neolithic of Ghana (2,500BC-1400/1000BC)17, are all separated from their succeeding states by a "silent" period of several centuries, while the Tichitt tradition neatly transitions into the inland Niger delta civilizations at the proto-urban settlement of Dia and the city of jenne-jeno, and ultimately into the Ghana empire, all in a region where an easily identifiable "tichitt diaspora" is attested both linguistically and archeologically.18

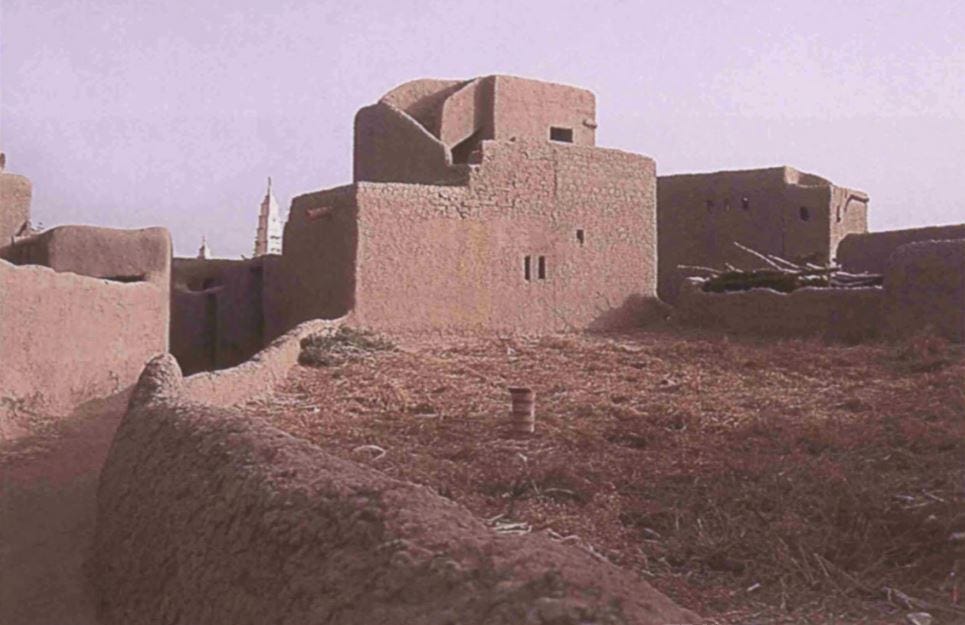

old section of Dia in Mali, the ancient city has been intermittently settled since the 9th century BC

West africa’s earliest state: the Ghana empire

foundations:

The formative period of Ghana isn’t well understood, initially, the extreme aridity of the "big dry" period from 300BC-300AD confined sedentism to the inland Niger delta region where the city of jenne-jeno flourished following the decline of Dia, the return of the wet period from 300-1000 CE, the introduction of camels and increased use of horses enabled the re-establishment of regional exchange systems between the Sahel and the Sahara regions that involved the trade of copper, iron, salt, cereal and cattle. Within these trade networks, a confederation of several competing Soninke polities emerged to control the various trading groups that managed these lucrative exchanges. Ghana established itself as the head of this confederation in the mid 1st millennium AD by leveraging its ritual primacy based on Ghana's centrality in the Soninkes’ "Wagadu" origin tradition; an oral legend about Dinga (the first king of Ghana) and its related serpent/ancestor religion practiced by the Soninke, the formation of Ghana is therefore dated to 300AD.19

Dinga, the first king of Ghana according to Soninke traditions, is also associated with various cities in the middle Niger such as Jenne-jeno and Dia, through which he passed performing various ritualistic acts involving the serpent cult before proceeding to Kumbi Saleh where he established his capital, the interpretation of this oral account varies but the inclusion of these cities situates them squarely within the early period of Ghana and has prompted some scholars to locate the early capital of the empire in the Mema region20 before it was later moved to Kumbi Saleh in the late first millennium where the earliest radiocarbon dates place its occupation in 500AD. This northward settlement movement of people from the Inland Niger delta region into what was formerly a dry region of southern Mauritania is also attested in the ruins of the tichitt tradition with the reoccupation of a number of tichitt sites around the 5th and 8th centuries that would later grow into the medieval oasis towns of tichitt and walata.21 By the 7th-8th century, Ghana’s political economy had grown enormously through levies on trade, and tribute, and the regional trade networks whose northern oriented routes had been confined to the central Sahara now extended to the north African littoral, specifically to the Aghlabid dynasty (800-909AD) in northern Algeria and southern Italy, where the earliest evidence of west African gold is attested.22 the Ghana empire’s political organization at this stage constituted a consolidated confederation of many small polities that stood in varying relations to the core, from nominal tribute-paying parity to fully administered provinces.23 and its during the 8th century that Ghana is first mentioned in external sources which provide us with most of the information about Ghana’s history until the 14th century.

Ghana first appears in external sources by al-Fazri (d. 777) who mentions it in passing as the “land of gold”. A century later in 872, al-Yaqubi writes that Ghana's king is very powerful, in his country are the gold mines and under his authority are several kingdoms, importantly however, al-Yaqubi's passage begins with the kingdom of Gao (kawkaw), that was located farther east of Ghana and which he describes as the "greatest of the realms of the sudan" thus summarizing west African political landscape in the 9th century as dominated by two large states.24 Its in the 10th and 11th century that Ghana reaches its apogee, with Ibn Hawqal in 988 describing Ghana's ruler as "the wealthiest king on the face of the earth", in the same passage where he describes Ghana’s western neighbor, the city of Awdaghust, which served as the capital of a Berber kingdom whose ruler maintains relations with the king of Ghana, and by the middle of the 11th century, the king of Ghana had conquered the city.25 In 1068, the most detailed description of Ghana is provided by al-Bakri, he names Ghana’s ruler as Tunka-Manin in 1063 whom he says "wielded great power and inspired respect as the ruler of a great empire", he also describes the empire’s capital Kumbi Saleh that was divided into a merchant section and a royal section which contained several palaces and domed buildings of stone and mud-brick; he describes Ghana's serpent/ancestor cult practices, its divine kingship, matrilineal succession, and royal burials. al-Bakri says that while many of Tunka-Manin’s ministers were muslims, he and his people venerated royal ancestors, he also mentions Ghana's south-western neighbor, the kingdom of Takrur and its eastern neighbor, the city of Silla with which Ghana was at war, and he adds that both of the latter are Muslim.26 al-Bakri also describes Ghana's wealth and opulence that “the sons of the [vassal] kings of his country wearing splendid garments and their hair plaited with gold.” and its military power that the king could “put 200,000 men in the field, more than 40,000 of them archers” in his battles against the kingdom of Takrur.27

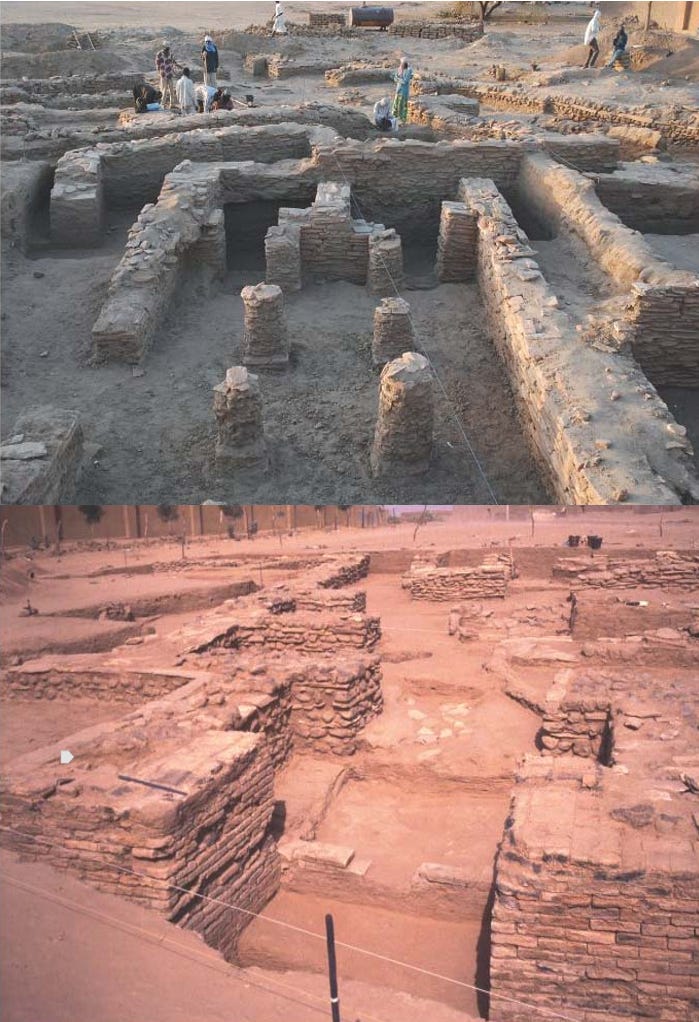

10-12th century ruins at Kumbi saleh of an elite house; and the great mosque. the earliest settlement at the city is dated to the 6th century AD, many of its houses were continuously rebuilt or built-over with more recent constructions until the 15th century when it was abandoned28

10th-13th century ruins at Awdaghust. the city’s earliest settlement is dated to the 7th century but extensive construction begun in the late 10th century.

Interlude: The adoption of Islam in west Africa, and Ghana's relationship with the Almoravid empire, the kingdoms of Takrur and Gao.

The mid-11th century political landscape of west Africa was a contested space, initially the states of Ghana and Gao controlled the inland Niger delta region and Niger-bend region respectively, as well as the lucrative trade routes that extended north Africa to west Africa, but the rise of the Takrur kingdom along the Senegal river (in Ghana’s south-west) and the city of Tadmekka (north-west of Gao) as important merchant states undermined the economic base of Ghana and Gao, but within a century, Ghana remained the sole political power in the region after a dramatic period of inter-state warfare, the adoption of Islam, shifting alliances and the meteoric rise and collapse of the Moroccan Almoravid empire.

west africa’s trade routes in the 17th century, most of these were already firmly established by the 11th century

The adoption of Islam in west Africa.

After centuries of trade and contacts between the west African states and the north African kingdoms, the west African rulers gradually adopted a syncretic form of Islam in their royal courts, the institution of this pluralist form of religion is explained by the historian Nehemiah Levtzion who observes that the religious role of west african kings necessitated that they cultivate and perform the cults of communal and dynastic guardian spirits as well as the cult of the supreme being, and for or the latter, they drew selectively from Islam. The religious life of the rulers was thus a product of the adaptation of a unified cosmology and ritual organization, and imams that directed the rituals for the chiefs were part of the court, like the priests of the other cults.29

Gao kingdom and the city of Tadmekka:

The earliest mention of islam's adoption in west Africa was the king of Gao in the 10th century. In the tenth century, al-Muhallabi (d. 985) writing about the kingdom of Gao, mentioned that "their king pretends before them to be a Muslim and most of them (his subjects) pretend to be Muslims too" He added that the ruler's capital (ie: Gao-Ancient) was west of the Niger river and that a Muslim market town called Sarna (ie: Gao-Saney) stood on the east bank of the river. Writing in 1068 al-Bakri states that, rulership in the Gao kingdom was the preserve of locals who he classified as Muslim, that when a new ruler was installed, he was handed "a signet ring, a sword, and a copy of the Qur'an" and that the reigning king was a “Sudanese” called Qandā (Sudan was the arabic label for black west-africans, besides Gao, it was also used for the rulers of Ghana, Mali, Takrur, etc but not for Awdaghust). but he also noted that the ruler's meals were surrounded by non-Islamic taboos and that many of Gao's professed muslims continued to venerate traditional objects.30 Gao flourished from the 8th to 10th century with a vibrant crafts industry in textiles, iron and copper smelting, and secondary glass manufacture, the city had massive dry-stone constructions including two palaces built by its songhai kings in the early 10th century at the site of “Gao-Ancient” but abandoned at the turn of the 11th century, when the region around it was settled by a new dynasty that was associated with the Ghana and Almorvaid empires.31 Gao’s trade faced competition from Tadmekka, its north-western neighbor. Tadmekka (also called Essuk) was founded in the 9th century and its inhabitants were reported by Ibn Hawqal as a mixed population of Berbers and west africans who were engaged in the lucrative gold trade of striking unstamped gold coins that were sold throughout north Africa. According to al-Bakri, no other city in the world resembled Mecca it did, and its very name was a metaphor comparing the religious and commercial role this town played in the Sahel to Mecca's role in Arabia, the city also possesses the oldest internally dated piece of writing known to have been produced in West Africa. 32Excavations at Essuk reveal that the city was established in the 9th century and flourished as a cosmopolitan settlement of Berbers and west Africans into the 10th century when it developed a vibrant crafts industry in gold processing, and secondary glass manufacture, by the 11th century. Tadmekka was a wealthy, well constructed town of dry-stone and mudbrick buildings containing several large houses and mosques occupied by a diverse population. Tadmekka’s Muslim population which was originally of the ibadi sect, later came to include other sects, hence the commissioning of Arabic inscriptions on cliffs and tombstones from 1010AD to 1216AD. The city was continuous occupied in the 13th and 14th centuries although its trade disappears from external references.33 Like Gao, the ruler of Tadmekka in the 11th century is described as Muslim.

10th century palaces at gao-ancient which became the capital of these songhai kingdom of gao after moving north from Kukiya-Bentya. These are the oldest discovered royal palaces in west africa, the large quantity of glass beads, copper ingots, iron goods and iron slag, crucibles, spindle whorls and earthen lamps, all demonstrate the extent of craft industries and trade at Gao34

Takrur kingdom, early Mali and the emergence of the Almoravid movement.

Al-Bakri also mentions the conversion of the king of Malal (an early Malinke polity that would later emerge as the empire of Mali) as well as the conversion of the Takrur ruler Wārjābī b. Rābīs (d. 1040) and the majority of his subjects who are all described as Muslims. while Takrur hadn't been mentioned in any of the earlier sources in the 10th century, it appears for the first time as a fully-fledged militant state that was fiercely challenging Ghana's hegemony from its south western flanks. al-Bakri writes that Wārjābī "introduced Islamic law among them”, and that "Today (at the time of his writing in 1068) the inhabitants of Takrur practice Islam."35 Takrur soon became a magnet for Islamic scholarship and a refugee for Muslim elites in the region, one of these was Abd Allāh ibn Yāsīn, a sanhaja Berber whose mother was from a village adjourning kumbi saleh,36 he had joined with another Berber leader named Yaḥyā b. Ibrāhīm in a holy war that attempted to unite the various nomadic Berber tribes of the western sahara under one banner —the Almoravid movement, as well as to convert them to Islam. This movement begun in 1048, one of their earliest attacks was on the Ghana-controlled Berber city of Awdaghust in 1055 (which is covered below), but they soon met stiff resistance in the Adrar region of central mauritania and Yaḥyā was killed in 1056 and the entire movement quickly collapsed, forcing ibn Yāsīn to contemplate a retreat to Takrur: "when Abdallah ibn Yasin saw that the sanhaja turned away from him and followed their passions, he wanted to leave them for the land of those sudanese (takrur) who had already adopted islam".37 Takrur's armies led by king Labi then joined the Almorvaids in 1056 to suppress rebellions and in the decades after and later contributed troops to aid the Almoravid conquest of morocco and Spain in the late 11th century. Takrur's alliance with the Almoravid movement influenced Arab perceptions of west African Muslims to the extent that until the 19th century, all Muslims from the so-called bilad al-sudan (land of the blacks) were called Takruri.38

While al-Bakri made no mention of Ghana's king as Muslim (unlike all its west african peers) he nevertheless mentions the existence of a Muslim quarter in the merchant section of Kumbi saleh that most likely constituted local converts and itinerant traders from the Sahara and from north Africa. Around 1055, the combined army of Takrur and the Almoravids attacked the city of Awdaghust and sacked it as graphically described by al-Bakri; "Awdaghust is a flourishing locality, and a large town containing markets, numerous palms and henna trees This town used to be the residence of the King of the Sudan.. it was inhabited by Zenata together with Arabs who were always at loggerheads with each other... The Almoravids violated its women and declared everything that they took there to be booty of the community…The Almoravids persecuted the people of Awdaghust only because they recognized the authority of the ruler of Ghana".39

The interpretation of this account about the conquest of Awdaghust is a controversial topic among west Africanists, not only for the graphic description of the violent attack and destruction of Awdaghust (which was similar to other violent descriptions of Almoravid conquests in morocco written by al-Bakri, who dismissed the Almoravids as a band of people lost at the edge of the known world whom he claims practiced a debased form of islam40), but also for the implication of Ghana's conquest based on the mention that Awdaghust had been the king's residence. The destruction of the city however isn't easily identifiable archeologically as the excavations show a rather gradual decline of the town that only starts in the late 12th century,41 by which time its collaborated by external accounts such as al-Idrisi’s in 1154 who writes that Awadaghust is "a small town in the desert, with little water, its population is not numerous, and there is no large trade, the inhabitants own camels from which they derive their livelihood". Nevertheless, the Almoravid conquest of Awdaghust probably triggered its downward spiral.42 But the claim that the Almoravids conquered Ghana on the other hand has since been discredited not only because of al-Idrisi’s 12th century description of Ghana at its height as a Muslim state but also its continued mention in later texts which reveal that it outlasted the short-lived Almoravid empire.

The Almoravid episode in Ghana's history.

Map of the Almoravid empire (1054-1147) and Ghana empire in the late 11th century

While Ghana was clearly not a Muslim state in al-Bakri's day, despite containing Muslim quarters in its capital, it did become a Muslim state around the time the Almoravids emerged. al-Zhuri gives the date of Ghana’s conversion as 1076 when he writes that "They became Muslims in the time of the Lamtunah (almoravids), and their Islam is good, today they are Muslims, with ulama, and lawyers and reciters, and they excel in that. Some of them, chiefs among their great men, came to the country of Andalusia. They travelled to Mecca performing the pilgrimage"43 Contemporary sources of the Almoravid era describe the circumstances by which Ghana adopted Islam which were unlikely to have involved military action or any direct dynastic change involving Almoravid nobles, because the rulers of Ghana continued to claim descent from a non-Muslim west African tribe44, the sources instead point to a sort of political alliance between Ghana and the Almoravids, the first of which was a letter from the king of Ghana addressed to the the “amir of Aghmat” named Yusuf ibn Tāshfin (who reigned as the Almoravid ruler from 1061-1106), the letter itself is dated to the late 1060s just before Yusuf founded his new capital Marakesh45. More evidence of a political alliance between Ghana and the Almoravids is provided by al-Zuhri who writes that Ghana asked for military assistance from the Almoravids to coquer the cities of Silla and Tadmekka with whom Ghana's armies had been at war for a period of 7 years, and that the "population of these towns became muslim"; this latter passage has been interpreted as a conversion from their original Islamic sect of Ibadism to the Malikism of the Almoravids (which was by then followed by Ghana as well), since both cities had been mentioned by al-Bakri as already Muslim several decades earlier.46

Lastly, there's evidence of an Almoravid-influenced architecture and tradition of Arabic epigraphy in the Ghana capital of Kumbi saleh (and in the city of Awdaghust), first is the presence of 77 decorated schist plaques with koranic verses in Arabic as well as fragments of broken funerary stela, while these were made locally and for local patrons, they were nevertheless inspired by the Almoravids.47 Secondly was the construction of an elaborately built tomb at Kumbi saleh between the mid 11th and mid 13th century where atleast three individuals of high rank (most likely sovereigns) were buried, this tomb had a square inner vault of dry-stone masonry measuring 5mx5m whose angles were hollowed out and contained four columns, its burial chamber, located 2 below, was accessible through an entrance and a flight of steps on the southwest side. While the design of this tomb has no immediate parallels in both west Africa and north Africa, a comparison can be made between al-Bakri's description of the tumuli burials of the Ghana kings, and the kubbas of the Almoravids, revealing that the “columns tomb” of Ghana combines both characteristics.48

the 11th/12th century columns tomb at Kumbi saleh, the remains of three individuals buried in this tomb were dated to between 1048-1251AD49

The dating of Ghana’s columns tomb to the 11th/12th century coincides with the dating of the slightly similar but less elaborately constructed kubba tomb at Gao-saney that was constructed in 1100, and is associated with the Za dynasty which took over the city after its original Songhai builders had retreated south.50 The sudden appearance of epigraphy in 12th century Gao may also provide evidence for theories which posit an extension of Ghana's political and/or religious influence to Gao51 Gao's epigraphy also confirms its connections with Andalusia (which in the 12th century was under Almoravid control). while the marble inscriptions from Gao-Saney were commissioned from Almeria (in Spain), their textual contents were composed locally and they commemorate three local rulers, they also commemorate a number of women given the Arabic title of malika ("queen"), not by virtue of being married or related to kings but serving in roles parallel to that of kings as co-rulers, a purely west-African tradition that parallels later descriptions of high ranking Muslim women in the empire of Mali and the kingdom of Nikki (in Benin), and conforms to the generally elevated status of west African Muslim women compared to their north African peers as described by Ibn Battuta in the 14th century.52

12th century commemorative stela of the enigmatic Za dynasty of Gao-Saney, inscribed in ornamental Kufic, The first is of king while the second is of a queen

Ghana’s resurgence and golden age

Ghana underwent a resurgence in the 12th century, and many of the formally independent polities and cities of west Africa are mentioned as falling under its political orbit. One of these polities now under ghana’s control was Qarāfūn (later called Zāfūn) al-Zuhri writes that "their islam was corrected by the people of ghana and they converted… and that they depended on Ghana because it is their capital and the seat of their Kingdom"53 Zāfūn had also been mentioned earlier by al-Bakri in 1068 as a non-Muslim state that followed the serpent/ancestor cult of Ghana54. next was the city of Tadmekka where al-Idrisī’s 1154 report noted that the khuṭba (or sermon usually delivered at Friday mosque and on other special occasions) was now delivered in the name of Ghana’s ruler, following the earlier mentioned attack on the city in the 1080s55. also included are the cities of Silā, Takrūr and Barīsā which now fell under the control of Ghana as al-idrisi writes that "All the lands we have described are subject to the ruler of Ghana, to whom the people pay their taxes, and he is their protector".56

The king of Ghana, according to al-Idrisi, was a serious Muslim who owed allegiance to the Abbasid caliph but at the same time having the prayer said in his own name in Ghana, and that the capital of Ghana was the largest, the most densely populated, and the most commercial of all the cities of the Sudan, he then continues to describe the warfare of the people of Ghana, the wealth of the empire and the new palace of the king about which he said "his living quarters are decorated with various drawings and paintings, and provided with glass windows, this palace was built in 1117AD"57, This is collaborated by archeological surveys at Kumbi saleh where the first dispersed form of settlement between the 8th and 10th century gave way to a period of intensive construction and dense urbanization from the 11th century and continuing into the 12th century, with large, dry-stone and mudbrick houses and mosques as well as a centrally located grand mosque, until the 14th century when the city when the city was gradually abandoned, estimates of the population of Kumbi Saleh range from 15,000 to 20,000 inhabitants and make it one of the largest west African cities of the 12th century.58

Many of the western Saharan oasis towns also flourished during the heyday of the Ghana empire, the majority of these cities were founded by speakers of Azer, a soninke language and were part of the confederation of soninke polities that were under Ghana’s control. The oldest among these oasis towns was Walata (Oualata) founded between the 6th century AD and originally named Biru, it became a regional market in the 13th century and competed against Awdaghust which was in decline at the time, it soon become a center of scholarship during the 13th century before its scholars moved to Timbuktu. The second oldest was Tıshit (Tichit) which was settled in the 8th century AD by the Masna (a soninke group that originally spoke Azer) not far from the neolithic ruins of dhar tichitt, it flourished in the 13th century and reached its apogee in the 15th century as a major exporter of salt. the last among the oasis cities was Wadan (ouadane) which was founded by Azer-speaking soninke groups in the late first millennium and became a veritable saharan metropolis by the late 12th century, the town's heyday was in the 16th century when it grew into a cosmopolitan city of 5,000 inhabitants that included a jewish quarter and a short-lived Portuguese outpost established in 1487, Wadan was only supplanted by its northern berber neighbor of shinqiti (chinguetti) in the 19th century. These three towns’ remarkable growth from the 12th/13th century onwards attests to the prosperity of the Ghana empire and its successor states during its "muslim era".59

ruins of the old town section of Walata, Mauritania. Walata was the first city of the Mali empire when approaching from the desert according to Ibn Battuta

ruined sections of the medieval town of tichitt and the old mosque which likely dates to between the 15th and 17th century.

the ruins of Wadan in Mauritania. most of its constructions, including the mosque in the second picture are dated to between the 12th and 16th century during its golden age, it was the focus of several Moroccan incursions in the 18th century but was only abandoned in the 19th century

Later writers such as Abu Hamid al-Gharnati, (d. 1170) continued to mention the prosperity of Ghana, referring to its gold and salt trade and that the subjects of Ghana made pilgrimages to Mecca60. The power of the ruler of Ghana is reflected in the respect accorded to him by the Almoravids who were commercially dependent on the fomer’’s gold; one of Ghana's kinglets, the ruler of Zafun, travelled to the Almoravid capital Marakesh, his arrival was recoded by Yaqut in 1220 but was doubtlessly describing events in the early 12th century "The king of Zafun is stronger than the latter (the Almoravids) and more versed in the art of kingship, the veiled people acknowledge his superiority over them, obey him and resort to him in all important matters of government. One year this king, on his way to the Pilgrimage, came to the Maghrib to pay a visit to the Commander of the Muslims, the Veiled King of the Maghrib, of the tribe of the Lamtuna (titles of the Almoravid rulers). The Commander of the Muslims met him on foot, whereas the King of Zafun did not dismount for him. A certain person who saw him in Marrakeh on the day he came there said that he was tall, of deep black complexion and veiled. He entered the palace of the Commander of the Muslims mounted, while the latter walked in front of him" some scholars have interpreted this as relating to the period of Almoravid decline when war with the emerging Almohad state increasingly undermined central authority at Marrakesh forcing the Almoravid rulers to seek support from their westAfrican ally; Ghana. Unfortunately for the Almoravids, the succession disputes that followed the death of their last great ruler Alî Ibn Yûsuf in 1143 eventually led to their empire's fall to the Almohads in 1147.61

Ghana maintained uneasy relations with their new northern neighbor, the Almohads, on one hand there was evidence of movement of scholars throughout both territories; west Africa's earliest attested scholar Yaqub al-Kanemi was educated in Ghana and later travelled to Marakesh in 1197 where he was recognized as a grammarian and poet and taught literature in the city's schools after which he moved to Andalusia62, but there was also political tension between Ghana and the Almohads, a letter from the Governor of the Moroccan city of Sijilmasa (an important entreport through which Ghana's gold passed) addressed to the king of the Sūdān in Ghāna was reproduced by al-Sarakhsi in 1203, saying; "we are neighbours in benevolence even if we differ in religion", the governor then complained of the ill treatment of his merchants in Ghana63, while some scholars have interpreted the "differ in religion" as Ghana having abandoned Islam, the written correspondence between Ghana and Sijilmasa which only started after the 1060s (as mentioned earlier) was conducted between Muslim rulers of equal might and could therefore only have been addressed to another Muslim, this is why other scholars interpret the complaint as part of the regional geopolitical contests in which Ghana’s ruler, by having the khuṭba delivered in his own name while evincing nominal fealty to the Abbasid caliph in Baghdad, effectively rejected Almohad suzerainty, especially since the Almohads didn't recognize the Baghdad caliph's authority unlike their Almoravid predecessors .64

Ghana may have continued expanding in the mid 13th century, when al-Darjini, writing in 1252, mentioned that the town (or capital) of Mali (ie Malal) was in the interior of Ghana, which reflected the suzerainty of Ghana over Mali, he also attributed the conversion of Mali's ruler from Ibadism to Maliki Islam by Ghana65, other writers such as Al-Qazwini (d.1283) continue to make mention of Ghana's wealth in gold and Ibn Said in 1286 who refers to Ghana's ruler as sultan (making this one of the earliest mentions of such a title on a west African ruler) and also mentions to him waging wars66. Despite some anachronistic descriptions, Ghana seemingly continues to exist throughout most of the 13th century at a time of great political upheavals that are mentioned in local traditions about its fall to the Soso and the subsequent rise of the Mali empire.

The gradual decline of Ghana in the 13th century is a little understood process that involved the empire’s disintegration into several successor states previously ruled by kinglets subordinate to Ghana, these states however, retained the imperial tradition of Ghana and Islam and continued to claim the mantle of Ghana which may explain the contradiction between the continued external references to Ghana in 13th and the political realities of the era, one of these successor states was the kingdom of Mema whose king was titled Tunkara (a traditional label for the ruler of Ghana) and another was Diafunu which some suggest corresponds with Zafun. Most of these sucessor states were subsumed by the expansive state of Soso, a non-Muslim Soninke kingdom from Ghana's southern flanks which was ultimately defeated in 1235 by Sudiata Keita, (the founder of the Mali empire), after his brief sojourn at the capital of the kingdom of Mema from where he took the legitimacy of the direct descendant of Ghana.67

By the time of Mansa Musa's pilgrimage to mecca in 1324, Ghana was a subordinate realm (together with Zafun and Takrur) within the greater empire of Mali as recorded by al-Umari (d. 1349) and latter confirmed by Ibn Khaldun in 1382.68 Mansa Musa is said to have rejected the title “king of Takrur” used by his Egyptian guests on his arrival at Cairo, because Takrur was only one of his provinces, but Ghana retained a special position in the Mali administration, with al-Umari writing that "No one in the vast empire of this ruler [of Mali] is designated king except the ruler of Ghana, who, though a king himself, is like his deputy"69 After this mention, Ghana and its successor states disappear from recorded history, its legacy preserved in Soninke legends of an ancient empire that was the first to dominate west Africa.

conclusion: the place of Dhar Tichitt and Ghana in world history.

The rise of social complexity in ancient west Africa is a surprisingly overlooked topic in world history despite the recent studies of the ancient polity at Dhar Tichitt that reveal its astonishingly early foundation which is contemporaneous with many of the “cradles” of civilization, and its independent developments that include; a ranked society, cereal domestication, metallurgy and monumental architecture, proving that the advent of civilization in west Africa was independent of “north-African” influences that were popular in diffusionist theories.

The continuity between the Tichitt neolithic and west African empires of Ghana and Mali, and latter’s unique form of administration which combined hierachial and heterachial systems of organization further demonstrates the distinctiveness of west African state building and how little of it is understood. As the athropologist George Murdock observed in 1959 "the spade of archaeology, has thus far lifted perhaps an ounce of earth on the Niger for every ton carefully sifted on the Nile", not much has changed in more the half a century that would situate Dhar Tichitt in its rightful place within world history;

the cradle of west Africa’s civilizations remains hidden away in the barren escarpments of the Mauritanian desert.

if you liked this article and wish to support this blog, please donate to my paypal

Read more about early west african and download books on my Patreon account

Encyclopedia of African History 3-Volume Set by Kevin Shillington pg 563

Sahel: Art and Empires on the Shores of the Sahara by Alisa LaGamma pg 49-55, reconceptualizing early ghana by SKntosh pg 369-371)

The Tichitt tradition in the West African Sahel by K MacDonald pg 505)

Background to the Ghana Empire by A. Holl pg 92-94)

The Tichitt tradition in the West African Sahel by K MacDonald pg 507)

Dhar Nema: from early agriculture to metallurgy in southeastern

Mauritania by K MacDonald etal pg 44)

Dhar Nema: from early agriculture to metallurgy in southeastern Mauritania by K MacDonald pg 42)

Betwixt Tichitt and the IND by KC MacDonald pg 66-67)

Dhar Tichitt, Walata and Nema: Neolithic cultural landscapes in the South-West of the Sahara by Augustin F.-C. Holl

Before the Empire of Ghana by KC MacDonald

Dhar Nema: from early agriculture to metallurgy in southeastern Mauritania by K MacDonald pg 44-45)

Time, Space, and Image Making: Rock Art from the Dhar Tichitt (Mauritania) by Augustin F. C. Holl pg 115)

Funerary monuments and horse paintings by William Challis pg 467-468)

Funerary monuments and horse paintings pg 465-466

A Chronology of the Central Nigerian Nok Culture – 1500 BC to the Beginning of the Common Era by Gabriele Franke

An Urewe burial in Rwanda by John Giblin

The Archaeology of Africa: Food, Metals and Towns by Bassey Andah pg 261

The Tichitt tradition in the West African Sahel by K MacDonald pg 510-512)

reconceptualizing early ghana by SK McIntosh pg 348-368)

The Peoples of the Middle Niger by Roderick James McIntosh pg 254-260)

Dhar Nema: from early agriculture to metallurgy in southeastern

Mauritania by K MacDonald pg 31)

Engaging with a Legacy: Nehemia Levtzion (1935-2003) by E. Ann McDougall pg 152

reconceptualizing early ghana by SK McIntosh pg 369-371)

Ancient Ghana and Mali by Nehemia Levtzion pg 15)

West African Early Towns by Augustin Holl pg 138-139)

Ancient Ghana and Mali by Nehemia Levtzion pg 16-28)

African Dominion: A New History of Empire in Early and Medieval West Africa by Michael A. Gomez pg 35-36)

Bilan en 1977 des recherches archéologiques à Tegdaoust et Koumbi Saleh (Mauritanie)

The History of Islam in Africa by Nehemia Levtzion pg 65-66)

Architecture, Islam, and Identity in West Africa by Michelle Apotsos pg 63)

Discovery of the earliest royal palace in Gao and its implications for the history of West Africa by Shoichiro Takezawa and Mamadou Cisse, Excavations at Gao Saney: New Evidence for. Settlement Growth, Trade, and Interaction on the. Niger Bend in the First Millennium CE by M Cissé

Sahel: Art and Empires on the Shores of the Sahara by Alisa LaGamma pg 119-220)

Essouk - Tadmekka: An Early Islamic Trans-Saharan Market Town pg 262-265)

Discovery of the earliest royal palace in Gao and its implications for the history of West Africa by Shoichiro Takezawa et Mamadou Cisse

A Geography of Jihad: Sokoto Jihadism and the Islamic Frontier in West Africa by Stephanie Zehnle pg 118)

Ancient Ghana and Mali by Nehemia Levtzion pg 33)

Ancient Ghana and Mali by Nehemia Levtzion pg 44)

A Geography of Jihad: Sokoto Jihadism and the Islamic Frontier in West Africa by Stephanie Zehnle pg 119)

the view from awdaghust by EA McDougall pg 8)

Sahel: Art and Empires on the Shores of the Sahara By Alisa LaGamma pg 118

West African Early Towns by Augustin Holl pg 134-135)

West African Early Towns by Augustin Holl pg 141-142)

Medieval West Africa: Views from Arab Scholars and Merchants pg 23)

The Conquest that Never was: Ghana and the Almoravids, 1076 by D Conrad pg 25)

The Conquest that Never was: Ghana and the Almoravids, 1076 by D Conrad pg 30)

The Conquest that Never was: Ghana and the Almoravids, 1076 by D Conrad pg 26-27)

Islam, Archaeology and History: Gao Region (Mali) Ca. AD 900-1250 by Timothy Insoll pg 70, almoravid inspiration see “Landscapes, Sources and Intellectual Projects of the West African Past” pg 194

First Dating of Columns Tomb of Kumbi Saleh pg 73

First Dating of the Columns Tomb of Kumbi Saleh (Mauritania) by C Capel

Excavations at Gao Saney: New Evidence for. Settlement Growth, Trade, and Interaction on the. Niger Bend in the First Millennium CE by M Cissé pg 13)

Ancient Kingdoms of West Africa pg 500-519)

Sahel: Art and Empires on the Shores of the Sahara By Alisa LaGamma pg 120-122),

The Conquest that Never was: Ghana and the Almoravids, 1076 by D Conrad pg 27)

The Golden Rhinoceros: Histories of the African Middle Ages by François-Xavier Fauvelle pg 78)

African Dominion: A New History of Empire in Early and Medieval West Africa by Michael A. Gomez pg 27)

Medieval West Africa: Views from Arab Scholars and Merchants pg 35

Medieval West Africa: Views from Arab Scholars and Merchants pg 32)

West African Early Towns by Augustin Holl pg pg 12-13)

"Saharan Markets Old and New, Trans-Saharan Trade in the Longue Duree" pg 81-87of ‘On Trans-Saharan Trails’ by Ghislaine Lydon

The Conquest that Never was: Ghana and the Almoravids, 1076 by D Conrad pg 28-29)

African Dominion: A New History of Empire in Early and Medieval West Africa by Michael A. Gomez pg 77)

Arabic Literature of Africa: The writings of central Sudanic Africa by John O. Hunwick pg 18)

The Conquest that Never was: Ghana and the Almoravids, 1076 by D Conrad pg 30)

African Dominion: A New History of Empire in Early and Medieval West Africa by Michael A. Gomez pg 40)

The Conquest that Never was: Ghana and the Almoravids, 1076 by D Conrad pg 33)

The Conquest that Never was: Ghana and the Almoravids, 1076 by D Conrad pg 33-34)

The peoples of the niger by Roderick James McIntosh pg 262)

The Conquest that Never was: Ghana and the Almoravids, 1076 by D Conrad pg 42)

From c. 500 B.C. to A.D. 1050 by J. D. Fage, Roland Anthony Oliver pg 379)

Amazing Article! I feel like Ghana is always given the short end of the stick and it's contribution to the states of the Niger bend that succeeded it is downplayed. Same with the fact the Almoravid myth has literally distorted so much of Ghana's history on the internet. There is a lot of things said in this article that shocked me. I did not know Ghana emerged to even become a stronger state, so much to the point that one of their kinglets asserted influence over the Almoravid king. I think in general, the history of the early Western Sudan is understudied and often misunderstood or just purposely distorted. Understanding the history of states like Ghana, Takrur, Gao and Tadmekka are central to understanding later Western Sudanese history. What is amazing is that the Soninke were still able to remain very influential even after the fall of Ghana, the ruling class of the Songhai empire was basically Soninke. I wonder however if there is a parallel to Ghana's contribution to the states of the Niger bend with the medieval Central Sahara (Garamantes, Zuwila, Kanem etc).

It is probably a lot more complex situation then west Africa since the kingdom of Zuwila was relatively a weak kingdom but had a lot of influence on early Kanem and vice versa. Kanem definitely was influenced greatly by the Fezzan, Kanem Oasis towns almost look extremely identical to Garamante towns (compare Djado to Garama for example) but overall Kanem asserted a lot more influence on the Fezzan then vice versa, not to mention the Tripoli-Bornu route that probably predates Islamic influence. Perhaps what the Ghana empire was to Mali was what the Garamantes were to Kanem (lets not forget the Garamantes also expanded as far as Nubia according to ptolemy).

and was there contact between the Garamantes and tichitt? don't know why but something like that could have very well been possible, do not remember where but I remember reading that the Ancient Fezzan and Tichitt could have influenced one another. Anyways, this was a amazing article, keep up the good work.

Brilliant, I am a soninke and extensively read about my origins but this is one of the most compelling,

best researched and most comprehensive essay about ancient Ghana/Wagadu.