Stone palaces in the mountains : Great Zimbabwe and the ruined cities of southern Africa

Debating a confiscated past

At the end of a torturous trail, after cutting through thick jungles, crossing crocodile infested rivers and battling "hostile" tribes, the explorer Carl Mauch arrived at a massive ruin, its walls, while overgrown, revealed a majestic construction towering above the savannah, and upon burning one of the pieces of wood and finding it smelled like cedar, he was elated, having found unquestionable evidence that "a civilized nation must once have lived here, white people once inhabited the region"1…. Or so the story goes.

Mauch had burned a piece of local sandalwood which he intentionally mistook for cedar (à la the cedar of Lebanon; ergo King Solomon), his publication received minor attention and he retired to his country into obscurity, falling off a ledge in 1875. It was Cecil Rhodes and his team of amateur archeologist yes-men who'd popularize the fable of Great Zimbabwe in the 1890s, tearing through burials and burrowing pits into its floor looking for evidence of a mythical gold-trading empire that controlled the precious metal from King Solomon's mines supposedly near Great Zimbabwe, which they surmised was built by ancient Semitic/white settlers, a grand fiction that they used in rationalizing their conquest of the colony then known as Rhodesia. Their actions sparked a mundane (but intense) debate about its construction, all while they were desecrating the site, melting the gold artifacts they could lay their hands on, exhuming interred bodies and burying colonial "heroes" in their place2. But by the 1930s, professional archeologists had shown beyond any doubt that the ruins were of local construction and of fairly recent origin, and in the late 1950s, one of the earliest uses of radiocarbon dating was applied at great Zimbabwe which further confirmed the archeologists’ findings, but the mundane debate carried on among the european settlers of the colony; what was initially a political project evolved into a cult of ignorance, that denied any evidence to the contrary despite its acceptance across academia in the west and Africa.

"Evidence" which the people of Zimbabwe who were living amongst these ruins had known ever-since they constructed them.

Unfortunately, after the “debate” about Great Zimbabwe's construction had been settled, there was little attempt to reconstruct the region’s past, over the decades in the 1970s and 80s, more ruins across the region were studied and a flurry of publications and theories followed that sought to formulate a coherent picture of medieval south-east Africa, but the limitations in reconstructing the Zimbabwean past became immediately apparent, particularly the paucity of both oral and written information about the region especially before the 16th century when most of the major sites were flourishing. The task of reconstructing the past therefore had to rely solely on the observations made by archeologists, while there’s a consensus on the major aspects of the sites (such as their dating to the early second millennium to the 19th century, their construction by local Shona-speaking groups based on material culture, and their status as centers of sizeable centralized states), other aspects of the Zimbabwe culture such as the region’s political history are still the subject of passionate debate between archeologists and thus, the history of the Zimbabwe culture is often narrated more as a kind of meta-commentary between these archeologist rather than the neat, chronological story-format that most readers are familiar with from historians. The closest attempt at developing the latter format for Great Zimbabwe and similar ruins was by the archeologist Thomas Huffman's "Snakes and crocodiles: power and symbolism in ancient Zimbabwe" but despite providing some useful insight into the formative period of social complexity in south-eastern Africa and on the iconography of the Zimbabwe culture, the book revealed the severe limitations of reconstructing the past using limited information3, and as another archeologist wrote about the book; "Snakes and Crocodiles suggests that we know a lot about the Zimbabwe State and the Zimbabwe culture… this is not so. Very basic information, such as the chronology of the wider region, has not yet been determined, basic archaeological data should be the starting point, not just intricate socio-economic theories or cognitive models derived from ethnography of people who lived centuries later"4. The complete understanding of the Zimbabwe culture is therefore not fully polished but the recent increase in studies of the ruins of south-eastern Africa by many archeologists active in the region, and the extensive research they have carried out that’s focused not just on the walled cities but their un-walled hinterlands has greatly expanded the knowledge about the region’s past allowing for a relatively more coherent picture of the region’s political history to emerge.

This article provides a sketch of the political history of Great Zimbabwe and the a few notable cities among the hundreds of similar ruins across south-eastern Africa; from its emergence in the early 2nd millennium to its gradual demise into the 19th century.

Sketch Map of the political landscape of medieval south-eastern Africa showing the main capitals and the extent of their Kingdom’s direct and indirect control

Support African History Extra by becoming a member of our Patreon community, subscribe here to read more about African history, download free books, and keep this newsletter free for all:

Origins of the “Zimbabwe culture”: the formative era of dry-stone construction, long-distance trade and the rise of complex states.

The region of south-eastern Africa had since the 1st century been occupied by agro-pastoralist groups of bantu-speakers who used iron implements and engaged in long distance trade with the east African coast and the central African interior, overtime, these agro-pastoralist groups clustered in village settlements and produced pottery wares which archeologists labeled Zhizo wares 5, The settlement layout of these early villages had a center containing grain storages, assembly areas, a cattle byre and a blacksmith section and burial ground for rulers, surrounded by an outer residential zone where the households of their wives resided, this settlement pattern is attested at the ruined site of K2 (Bambandyanalo) in the 11th century arguably one of the first dzimbabwes (houses of stone)6; K2 was the largest of the settlements of the Leopard's Kopje Tradition, an incipient state that is attested across much of region beginning around 1000AD when its presumed to have displaced or assimilated the Zhizo groups. By the 1060AD, the cattle byre had been moved to the outside of the settlement as the latter grew and after the decline of K2 in the early 13th century, this settlement pattern seemingly appears at Mapungubwe, a similar dzimbabwe in north eastern south Africa, its here that one of the earliest class-segregated settlement emerged with scared leaders residing on lofty hills associated with rainmaking in their elaborately built stone-walled palaces with dhaka floors (impressed clay floors), which after Mapungubwe’s collapse in 1290 AD was again apparently transferred to Great Zimbabwe7.

the ruins of K2 (bottom right), Mapungubwe Hill (top left) and collapsed walls of Mapungubwe, both in south Africa

Despite its relative popularity, this settlement pattern of reclusive kings residing on rainmaking hills, as well as the supposed transition from K2 to Mapungubwe in the 13th century, then to Great Zimbabwe in the 14th century (and after that to Khami in the 15/16th century and Dananombe in the 17th century) has however been criticized as structuralist by other archeologists. Firstly; because the connection between Mapungubwe and Great Zimbabwe is virtually non existent on comparing both site’s material cultures and walling styles8 (Mapungubwe’s walls were terraces while Great Zimbabwe's were free-standing) but also because the typical dzimbabwe features of stone-walled palaces, dhaka floor houses and hilltop settlements occur across much of the landscape at sites that are both contemporaneous with K2 and Mapungubwe but also occur in some sites which pre-date both of them; for example at Mapela in the 11th century9, at Great Zimbabwe's hill complex in the 12th century10, and in much of south-western Zimbabwe and north-eastern Botswana where archeologists have identified dozens of sites predating both Mapungubwe and Great Zimbabwe. All of which have hilltop settlements, free-standing and terraced dry-stone walls and more importantly; gold smelting which later became important markers of elite at virtually all the later dzimbabwes.

The sites in north-eastern Botswana lay within the gold belt region which both Mapungubwe and Great Zimbabwe fall out of and would have thus required to trade with them to obtain gold, these sites are part of the Leopard's kopje tradition as well and are clustered around the Tati branch of the Shashe river, they include the 12th century site of Tholo, and the 13th century site of Mupanipani, the leopard's Kopje state is itself contemporaneous with the Toutswe chiefdom, an incipient state in north-eastern Botswana whose dry-stone settlements shared some similarities with the leopard's kopje state11.

As the archeologist Shadreck Chirickure observes; given the higher frequency of pre-13th century dzimbabwes in the region of south-western Zimbabwe and north-eastern Botswana compared to the few sites in northern south Africa where K2 and Mapungubwe are found, he concludes that, “the advent of the Zimbabwe culture is evident from the distribution of many leopard's kopje sites most of which remain understudied, it would be somewhat inane to argue that it is possible to identify the first palace in the Zimbabwe culture, the first dhaka floors and the first rainmaking hill, rather it is possible to see a network of actors who exhibit shared cultural traits occasioned by various forms of interaction".12

the ruins of Mapela in Zimbabwe and Mupanipani in Botswana that were contemporaneous with k2 and Mapungubwe

Map showing the pre-1300 dzimbabwes of South-eastern Africa

Putting this all together, the picture that emerges from the late 1st and early 2nd millennium south-eastern Africa is that the political landscape of the region was dominated by several incipient states that competed, conflicted and interacted with one another and whose elites constructed elaborate stone-walled residences often on hilltops with both the free-standing and terraced walls and dhaka floors, these features were soon adopted by surrounding settlements through multiple trajectories and which grew into the centers of relatively larger kingdoms by the 13th century such as Mapunguwe, Zimbabwe, Khami and Thulamela.13

Medieval southern Africa from the 13th to the 16th century: A contested political landscape of multiple states.

The city of Great Zimbabwe emerged around the 12th century and was occupied until the early 19th century, the urban settlement was first established on the hill complex from where it expanded to the great enclosure and the valley ruins14, the built sections cover more than 720ha and they housed both “elite” and "commoner" residences, ritual centers and public forums.

The city is comprised of three major sections that include the hill complex located at the top of a 100m-high hillrock: this labyrinthine complex was the earliest of the city's sections, its walls rise over 10 meters with pillars surmounted with stone monoliths, it extended over 300meters on its length and 150 meters on its breadth, inside are the remains of house floors grouped in compounds that were separated by high drystone walls and accessed through a complex maze of narrow passages with paved floors and staircases, as well as ritual sections with ceremonial objects such as soapstone birds and bronze spearheads.

The entire section's walls are built along precipitous cliffs and take advantage of the naturally occurring granite boulders. The second section is the great enclosure with its 11 meter high walls built in an elliptical shape, it encloses several smaller sections accessed through narrow passages one of which leads to a massive conical tower and a stone platform at the center, lastly are the valley ruins that are comprised of several low lying walled settlements next to the great enclosure, and they contained hundreds of houses.15

The ruins of Great Zimbabwe; the Hill complex (first two sets of photos), the Great enclosure (next two sets of photos) and the Valley ruins (last photo; right half)

Previous studies suggested that the hill complex at Great Zimbabwe (and similar prominent sections in other dzimbabwes) were used for rainmaking rituals, with limited occupation save for the king and other royals, and that the valley housed the wives of the ruler, and that the city had an estimated population of around 18,000-20,00016.

But this approach has since been criticized given the evidence of extensive occupation of the hill complex site from the early 2nd millennium which goes against the suggestion that it was reserved as the King's residence, as well as the valley ruins which evidently housed far more than just the King’s wives. The Hill complex’s supposed use as a rainmaking site has also been considered a misinterpretation of Shona practices "Based on logic where rain calling is part of bigger ideological undercurrents related to fertility and performed in the homestead and outside of it, arguing that the hill at Great Zimbabwe was solely used for rain making and was not a common settlement is similar to arguing that Americans built the White House for Thanksgiving"17.

Further criticism has been leveled against the population estimates of Great Zimbabwe, as that the region of south-east Africa generally had a low population density in the past and Great Zimbabwe itself likely peaked at 5,00018 rather than the often-cited 18,000-20,000, and the entire site was never occupied simultaneously but rather different sections were settled at different times as a result the region’s political system where each succeeding king resided in his own palace within the city; this was best documented in the neighboring northern kingdom of Mutapa, and is also archeologically visible in similar sites across the region such as Khami, where power would attimes return to an older lineage explaining why some sections were more heavily built and occupied longer than others.19

The autonomous ruling elites of the overlapping states of medieval southern Africa also shared a complex inter-state and intra-state heterarchical and hierarchical relationship between each other with power oscillating between different lineages within the state as well as between states..20 This form of political system was not unique to south-east Africa and but has been identified at the ancient city of Jenne-jano21 in Mali as well as the kingdom of Buganda22 in Uganda. Both long distance trade and crafts production such as textiles, iron, tin and copper tools and weapons, pottery, sculptures at the site were largely household based rather than mass produced or firmly regulated under central control explaining the appearance of imports and "prestige goods" in both the walled and un-walled areas in Great Zimbabwe23 as well as Khami24, although the sheer scale of construction at Great Zimbabwe nevertheless shows the extent that the kings could mobilize labor, especially the great enclosure with its one million granite blocks carved in uniform sizes and stacked more than 17ft wide, 32ft high.25

The abovementioned reduction in Great Zimbabwe’s population estimates has also led to the paring down of the estimated size of the kingdom of Zimbabwe, far from the grandiose empire envisioned by Rhodes’ amateur archeologists that was supposedly centered at Great Zimbabwe in which the other ruins in the region functioned as "forts built by the ancients to protect their routes"26, the kingdom of Zimbabwe instead flourished alongside several competing states such as the Butua kingdom at Khami in the south-west, the Kingdom of Thulamela in the south27 another state based at Danangombe, Zinjaja and Naletale 28 (which later became parts of the Rozvi kingdom) as well as other minor states at Tsindi and Harleigh Farm29.

The kingdom of Zimbabwe is thus unlikely to have extended its direct control beyond a radius of 100km, nevertheless it controlled a significant territory in south-eastern Zimbabwe especially between the Runde and Save rivers with nearby settlements such as Matendere, Chibvumani, Majiri, Mchunchu, Kibuku and Zaka falling directly under its control, these sites flourished between the 13th and 15th centuries and feature free-standing well-coursed walls similar to great Zimbabwe’s albeit at a smaller scale30.

the Matendere ruins

The ruins of Chibvumani and Majiri

As one of the major powers in south-eastern Africa that controlled the trade routes funneling gold, ivory and other interior commodities to the coast, Great Zimbabwe traded extensively with the coastal city states of the Swahili (a bantu-speaking group that built several city-states along the east African coast) with which it exchanged its products especially gold (estimated to have amounted to 8 tonnes a year before the 16th century31) for Indian ocean goods such as Chinese ceramics and Indian textiles; the discovery of a Kilwa coin at great Zimbabwe32 as well as the flourishing of a string of settlements along the trade routes through Mozambique and its coast eg Manyikenyi and Sofala between the 12th and 15th century33 was doubtlessly connected to this trade. It also traded extensively with the central African kingdoms in what is now DRC and Zambia from where copper-ingots were imported34.

Related to the above criticism, Great Zimbabwe is thus shown to have flourished well into the 16th and 17th century35 which overlapped with the height of the neighboring kingdoms of Butua, Mutapa, Thulamela as well as similar sites such as Tsindi and Domboshaba36, and the supposed transfer of power from Great Zimbabwe to Khami and the kingdom of Mutapa is rendered untenable, so is the suggestion that environmental degradation caused its collapse37. The political landscape of south-eastern Africa from the 13th to the 16th century was thus dominated by several states with fairly large capitals ruled by autonomous kings.

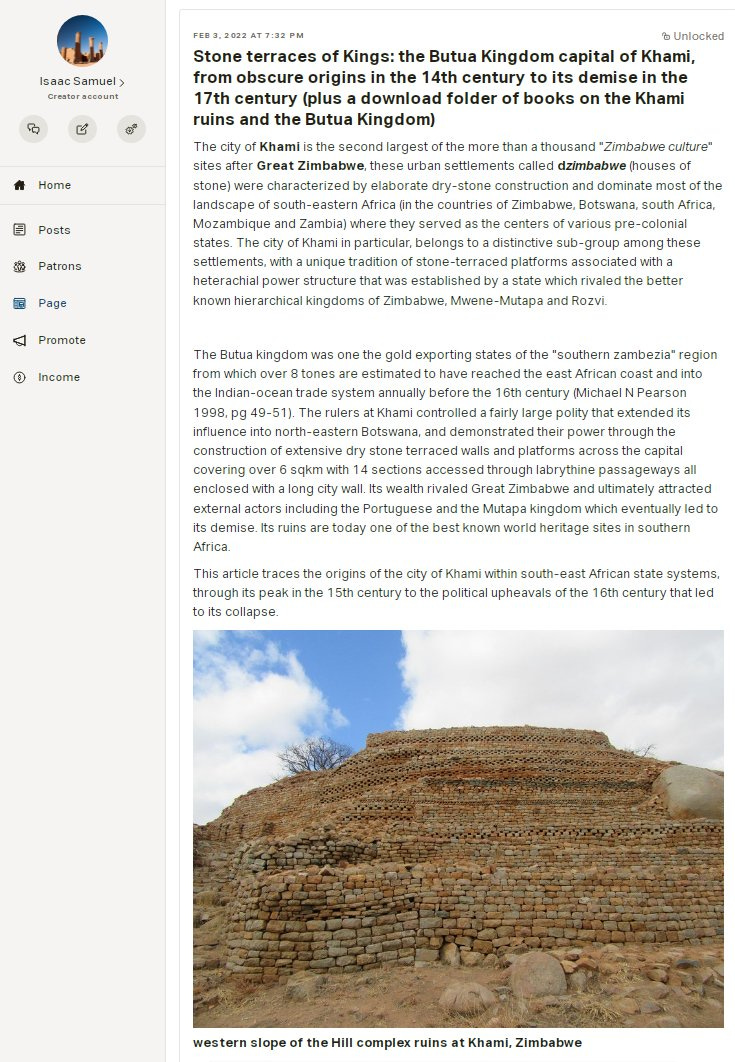

The ruins of Khami in Zimbabwe; the Hill complex, Passage ruin and the Precipice ruins

The ruins of Naletale in Zimbabwe

The ruins of Danangombe in Zimbabwe

the ruins of Tsindi in Zimbabwe

The ruins of Majande and Domboshaba in Botswana

Garbled history and the silence of Great Zimbabwe: claims of a 16th century Portuguese account of the city, and the beginning of the Great Zimbabwe debate.

The appearance of the Portuguese in the early 16th century Mutapa as well as the northern Zimbabwe region's better preservation of oral accounts provide a much clearer reconstruction of its past; showing a continuity in the Zimbabwe culture architectural forms of dry-stone construction, the rotational kingship, the rain-making rituals, the agro-pastoralist economy, the gold trade to the east African coast and the crafts industries38, but unfortunately, little can be extracted from these accounts about the history of the southern kingdoms where Great Zimbabwe, Khami, Danangombe and Thulamela were located.

The famous mid-16th century account of the Portuguese historian João de Barros whose description of a dry-stone fortress called Symbaoe located to the south of the Mutapa kingdom, surrounded by smaller dry-stone fortress towers, and seemingly alluding to Great Zimbabwe was is fact an amalgamation of several accounts derived from Portuguese traders active in the Mutapa kingdom but with very distorted information since the traders themselves hadn't been to any of the southern regions having confined their activities to Mutapa itself.39

The archeologist Roger summers has for example argued that the Matendere ruin is likely the best candidate for de Barros’ description rather than Great Zimbabwe40, yet despite this attempt at matching the textual and archeological record, De Barros’ mention that Symbaoe was located within the “Torwa country” of the “Butua kingdom” (which are traditionally associated with the terraced city of Khami rather than the free-standing walls of Great Zimbabwe) further confuses any coherent interpretation that could be derived from this account. Unfortunately however, Duarte's inclusion of a claim that Symbaoe was “not built by natives” but by “devils” (which is a blatant superimposition of European mythology about the so-called “devil’s bridges”41) marks the beginning of the debate on the city’s construction, as colonial-era amateur historians and archeologists held onto it as proof that it wasn't of local construction despite other Portuguese writers’ description of similar dry-stone constructions surrounding the palaces of the Mutapa King eg an account by Diogo de Alcacova in 1506 describing a monumental stone building at the Mutapa capital, as well as a more detailed description offered a few decades later by Damiao de Goes, a contemporary of de Barros (its hard to tell who plagiarized the other) who instead associates the great fortress of Symbaoe to the king of Mutapa42.

Later Portuguese accounts such as Joao dos Santos in 1609 would distort the above descriptions further by weaving in their own fables about King Solomon's gold mines which they claimed were located near Sofala43 (ironically nowhere near Great Zimbabwe) but likely as a result cartographers of late 16th century such as Abraham Ortelius in 1570 making maps that were labeling King Solomon's mines (the biblical Ophir) as “Symbaoe” and placing them in south-east Africa44. The 16th century Portuguese claims of a gold-mine in the interior was part of the initial wave of the Portugal's expansionist colonial project to conquer the Mutapa kingdom as they had developed a deep interest in its gold, seizing Sofala (the region’s main seaport), briefly conquering much of the Swahili coastal cities in the mid 16th century, as well as establishing a string of dozens of interior settlements —exclusively as mining towns— in the Mutapa kingdom, and also founding trading stops in the region of northern Mozambique.

By the 17th century, many western European maps, from England to Italy, already identified the legendary Ophir as Symbaoe in south-eastern Africa, even literary works such as John Milton’s Paradise Lost (1667) referred to “the Ophir of southern Africa”, and the idea of a dry-stone city in the interior of southern Africa built by some "foreigners", a "ancient lost tribe" or "devils" continued well into the 18th century, with the Portuguese governor of Goa (in India) in 1721 writing about a large dry-stone fortress in the capital of the Mutapa kingdom, which he claims wasn't constructed by the locals.45

After this however, interest in the ruins of Zimbabwe was followed by a century of silence until the elephant hunter Adam Renders was guided to the ruins in 1868 and later the explorer Karl Maunch "stumbled upon” the ruins after being directed to them by Renders, their “discoveries” coinciding with a second wave of colonial expansionism in south-eastern Africa.

golden rhinoceros, bovine and feline figures, scepter, headdress and gold jewelry from the 13th century site of Mapungubwe (University of Pretoria Museums, Museum of Gems and Jewellery, Cape Town) .The total Mapungubwe collection weighs alittle over 1kg but its dwarfed by the gold jewellery stolen from Danangombe that weighed over 18kg and a total of 62kg of such artefacts were smelted down by Cecil Rhodes’ Ancient ruins company and their value to archaeology lost forever.

Gold jewelry from Thulamela (originally at the Kruger National park)

Warfare, diplomacy and conquest in 17th century south-east Africa: Civil strife in Mutapa, the sack of Khami, the rise of the Rozvi kingdom and the decline of Great Zimbabwe and Thulamela

Let’s now turn back to the initial wave of Portuguese colonial expansion in the 16th and 17th century, this was a period of political upheaval in south-east Africa with large scale warfare seemingly at a level that wasn't apparent in the preceding era, marked by the proliferation in the construction of "true" fortifications with loop-holes for firing guns and other missile weapons especially across northern Zimbabwe in the Mutapa heartland which was a direct consequence of the succession crises in the kingdom caused by several factors including; rebellious provinces whose claim to the throne was as equal as the ruling kings, Mutapa rulers leveraging the Portuguese firepower to augment their own, Portuguese attempts to conquer Mutapa and take over the mining and sale of gold, and migrations of different groups into the region46. But since the Mutapa wars are well documented, ill focus on the southern wars.

Hints of violent intra-state and interstate contests of power between the old kingdoms of region are first related in a late 15th century tradition about a rebellion led by a provincial noble named Changamire (a title for Rozvi chieftains in the Mutapa kingdom) against the Mutapa rulers, using the support of the Torwa dynasty of the Butua kingdom, but this rebellion was ultimately defeated. Around 1644, a succession dispute in the Butua kingdom between two rival claimants to the throne ended with one of them fleeing to a Portuguese prazo (title of a colonial feudal lord in south-east africa) named Sisnando Dias Bayão from whom he got military aid, both of them arriving at Khami with cannon and guns where they defeated the rival claimain’s army and sacked the city of Khami.

Dias Bayão was assassinated shortly after, and the new Butua ruler made brief attempts to expand his control north into a few neighboring Portuguese settlements. By the 1680s, a new military figure named Changamire Dombo led his armies against the Mutapa forces whom he defeated in battle, he then turned to the Portuguese at the battle of Maungwe in 1684 and defeated them as well, when succession disputes arose again in Mutapa in 1693, Chagamire sided with one of the claimants against the other who was by then a Portuguese vassal, Changamire's armies descended on both Mutapa and Portuguese towns such as Dambarare and killed all garrisoned soldiers plus many settlers, razing their forts to the ground and taking loot, the few survivors fled north and tried to counterattack but Changamire's forces defeated them again in Manica in 1695, expelling the Portuguese from the interior permanently.47

While its claimed that Chagamire Dombo was supported by the Butua kingdom (in a pattern similar to the 15th century Chagamire rebellion), this time Khami wasn't spared but the city was razed to the ground by Changamire's forces in the mid-1680s and depopulated48, there's abundant archeological evidence of burning at Khami's hill complex with fired floors and charred pots, as well as ceremonial devices and divination dices left in situ, as its inhabitants fled in a hurry abandoning the ancient city to its fiery end49. Coinciding with this political upheaval was the abandonment of Thulamela in the 17th century, this town had flourished from the 13th century and peaked in the 15th and 16th century with extensive gold working and imported trade goods, just as Khami and Great Zimbabwe were at their height50.

As Changamire's Rozvi state moved to occupy the cities of Danangombe, Naletale and Manyanga with their profusely decorated walls and extensive platforms where he constructed his palace and in which were found imported trade objects and two Portuguese canon seized from one of his victories51 , Rozvi's armies are reputed to have campaigned over a relatively large territory parts of which had previously been under the control of the Butua Kingdom and Mutapa kingdom , its unlikely that Great Zimbabwe was out of their orbit, a suggestion which may be supported by the decline in its settlement after the 17th century, but the extent of Rozvi control of the region is unclear and recent interpretations suggest that stature of the Rozvi has been inflated.52

The ruins of Thulamela in south Africa

The ruins of Taba zikamambo (Manyanga) in Zimbabwe

muzzle loading cannon from the Portuguese settlement of Dambarare found at Danangombe after it was taken by Changamire’s forces

In the early 18th century, succession disputes led to the migration of some of his sons to found other states which would be mostly autonomous from the Rozvi, one went to in northern South Africa where he established his capital at Dzata in the 18th century53, another moved to the region of Hwange in north-western zimbabwe and established the towns of Mtoa54 Bumbusi and Shangano55 in the 18th and early 19th centuries, there was no building or settlement activity at great Zimbabwe by this time and occupation had fallen significantly.

The ruins of Mtoa and Bumbusi in Zimbabwe

The ruins of Dzata in south Africa

Map of 103 of the better known dzimbabwes until the 19th century, their total exceeds 1,000 sites.

Disintegration, warfare and decline: the end of the Zimbabwe culture in the 19th century

The early 19th century witnessed another round of political upheaval and internecine warfare associated with the migration (Mfecane) into the region by various groups including Nguni-speakers, Tswana-speakers and Ndebele-speakers, who came from the regions that are now in south Africa and southern Botswana and were migrating north as a result of the northward migration of the Dutch-speaking Boer settlers who were themselves fleeing from British conquests of the cape colony, coupled with the increasing encroachment of the Portuguese from Mozambique into parts of eastern Zimbabwe, the rising population in the region and the founding of new states that eventually extinguished the last of the dzimbabwes; with the flight of the last Changamire of Rozvi kingdom occurring in the 1830s after he had been defeated by the Nguni leader Nyamazama, and by the 1850s, the Ndebele took over much of the Rozvi heartland, absorbed the remaining petty chiefs and assimilating many of the Rozvi into the new identity in their newly established state which was later taken by the advancing British colonial armies under Cecil Rhodes in the 1890s.56

Cecil Rhodes’s expansionism was driven by the search of precious minerals following the discovery of diamonds at Kimberly in 1869 and gold in the highveld in 1886, as well as the flurry of publications of the fabled mines of king Solomon supposedly near the dry-stone ruins across the region, By then only a small clan occupied Great Zimbabwe57, the last guards of southern Africa's greatest architectural relic.

Great Zimbabwe: a contested past

The ruin of Great Zimbabwe is arguably Africa’s most famous architectural monument after the ancient pyramids and they were for many decades in the 20th century at the heart of an politically driven intellectual contest for the land of Zimbabwe instigated by the colonial authorities and the european settlers’ elaborate attempt at inserting themselves in a grand historical narrative of the souhern african past, inorder to support their violent displacement and confiscation of land from the African populations whom they had found in the region, this begun with the infamous colonial wars fought between the Matebele kingdom and the Cecil rhodes’ British South Africa Company that involved nearly 100,000 armed men rising to defend their kingdom against a barrage of machine gun fire, after more 2 wars involving many battles, Rhodes took over what became the colony of Rhodesia. He had by then established the ancient ruins company in 1895 (after the first Matebele war) with the exclusive objective of plundering of the ancient ruins of south-east Africa —as the name of the company clearly states-- this included Great Zimbabwe, from where his “treasure hunters” took several soapstone birds, but the largest loot was taken from Danangombe where more than 18kg of gold was stolen from elite graves in 1893 by the American adventurer F.R. Burnham, and another 6kg taken from the Mundie ruin not far from Danangombe by Cecil rhodes’ colleagues, both loot were sold to Cecil Rhodes; which prompted the formation of the formation of the ancient ruins company, which by 1896 had stolen another 19.8kg of gold in just six months, resuming after the second Matebele war to steal even more gold from over 55 ruins totalling over 60 kg, which included jewelry, bracelets, beads and other artifacts that they melted and sold.58 before the company was closed in 1900 after attracting rival looters and doing irreparable damage to the sites.

Photos of some of the Gold objects and jewelry stolen from the ruins of Danangombe and Mundie (from: The ancient ruins of Rhodesia by Richard Hall)

Earlier in 1891 on his first visit to Great Zimbabwe, Rhodes told the ruler of Ndebele; King Lobengula (whose armies his company would later fight) that “the great Master has come to see the ancient temple which once upon a time belonged to white men"59Rhodes then begun an intellectual project with his army of amateur archeologists such as Theodore bent and Richard Hall (whose “digs” he sponsored)60 with the intent to deny any claims of the Africans’ construction of great Zimbabwe, by weaving together the vague references to the Solomon’s mines from Portuguese accounts, with the diffusionist and Hamitic-race theories popular at the time to create a story in which him and the European settlers he came with could legitimize their plunder by claiming that their right to settle the lands of Zimbabwe was stronger than the Africans whom he found.61 But having no real academic background or training in archeology, Bent and Hall’s findings —published in 1902 and 1905— were disproved almost immediately by the professional archeologist Randal Mc-Iver in 1906 who proved Great Zimbabwe’s African origin, writing that "the people who inhabited the elliptical temple belonged to tribes whose arts and manufacture are indistinguishable from those of the modern Makalanga”62 (the Kalanga are a shona-speaking group), although consensus wouldn’t shift to his favor until his studies were confirmed by Gertrude Caton-Thompson in 1931 after her extensive digs in several ruins across the region proved beyond doubt that the ruins were of local construction, effectively ending the “debate” at least in academic circles63.

The so-called Great Zimbabwe debate was therefore nothing more than an obtuse fiction intended to legitimize Rhodes’ conquest of Zimbabwe, but one which retained a veneer of authenticity among the Rhodesian settlers, a “cavalcade of fact and fantasy” re-enacted by Rhodesian apologists and a few western distracters to deny African accomplishments, its specter looming over modern professional debates that seek to reconstruct the Zimbabwean past, and clouding our understanding of one of the most fascinating episodes of African history.

for more on African history including the history of the Butua kingdom of Khami as well as free book downloads on south-east africa’s history, please subscribe to my Patreon account

The Lost White Tribe by Michael F. Robinson pg 112-113)

Great Zimbabwe: reclaiming a 'confiscated' past · by Shadreck Chirikure pg 9

Reviewed Work: Snakes and Crocodiles: Power and Symbolism in Ancient Zimbabwe by Thomas N. Huffman; Review by: David Beach, M. F. C. Bourdillon, James Denbow, Martin Hall, Paul Lane, Innocent Pikirayi and Gilbert Pwiti.

The origin of Zimbabwe Tradition walling by by C Van Waarden pg 72)

The Zimbabwe culture by Innocent Pikirayi pg 77-83)

Theory in Africa, Africa in Theory by Stephanie Wynne-Jones pg 116-120)

Theory in Africa, Africa in Theory by Stephanie Wynne-Jones pg 120-125)

The origin of Zimbabwe Tradition walling by by C Van Waarden pg 57-68)

Zimbabwe Culture before Mapungubwe by S Chirikure pg2)

Dated Iron Age sites from the upper Umguza Valley by Robinson, K. R, pg 32–33),

The origin of Zimbabwe Tradition walling by by C Van Waarden 59-71)

zimbabwe Culture before Mapungubwe by S Chirikure pg 17)

New Pathways of Sociopolitical Complexity. in Southern Africa. by Shadreck Chirikure pg 356, 361

Great Zimbabwe: reclaiming a 'confiscated' past · by Shadreck Chirikure pg 102-104)

The Zimbabwe culture by Innocent Pikirayi pg 129-140)

Snakes & Crocodiles by Thomas N. Huffman

Great Zimbabwe: reclaiming a 'confiscated' past · by Shadreck Chirikure pg 230-232)

What was the population of Great Zimbabwe (CE1000 – 1800)? by S Chirikure pg 9-14)

When science alone is not enough by M. Manyanga and S. Chirikure

No Big Brother Here by Shadreck Chirikure, Tawanda Mukwende et. al pg 18-19)

Beyond Chiefdoms: Pathways to complexity in Africa by S.K McIntosh

Mapping conflict: heterarchy and accountability in the ancient capital of Buganda by H Hanson

New Pathways of Sociopolitical Complexity. in Southern Africa. by Shadreck Chirikure pg 359)

The chronology, craft production and economy of the Butua capital of Khami, southwestern Zimbabwe by Tawanda Mukwende et al. pg 490-503)

Great Zimbabwe by Peter S. Garlake pg 31

The Zimbabwe culture by Innocent Pikirayi pg 141

Late Iron Age Gold Burials from Thulamela

Landscapes and Ethnicity by LH Machiridza pg

When science alone is not enough by M. Manyanga and S. Chirikure pg 368-369)

The Zimbabwe culture by Innocent Pikirayi pg 142-147)

Port Cities and Intruders by Michael N Pearson pg 49-51

The Swahili World by Stephanie Wynne-Jones pg 449

The Swahili World by Stephanie Wynne-Jones pg 179, 308

The Zimbabwe culture by Innocent Pikirayi pg 145-146, 148)

Elites and commoners at Great Zimbabwe by S. Chirikure pg 1071

New Pathways of Sociopolitical Complexity. in Southern Africa. by Shadreck Chirikure pg 355-356

Great Zimbabwe: Reclaiming a 'Confiscated' Past By Shadreck Chirikure pg 229

A Political History of Munhumutapa, C1400-1902 by S. I. G. Mudenge

The Mutapa and the Portuguese by S. Chrikure et.al

Ancient Ruins and Vanished Civilisations by Roger Summers 49-51)

Christian Mythology: Revelations of Pagan Origins By Philippe Walter

The Zimbabwe Culture: Ruins and Reactions by G. Caton-Thompson. pg 86)

The Lost White Tribe by Michael F. Robinson pg 111

The Lost White Tribe by Michael F. Robinson pg 111-112

The Zimbabwe Culture: Ruins and Reactions by G. Caton-Thompson pg 88)

The Zimbabwe culture by Innocent Pikirayi pg pg 184-195)

A History of Mozambique By M. D. D. Newit 102-104

The Archaeology of Khami and the Butua State by by T Mukwende pg 14)

Great Zimbabwe: Reclaiming a 'Confiscated' Past By Shadreck Chirikure pg236)

Late Iron Age Gold Burials from Thulamela by M Steyn pg 84)

The Zimbabwe culture by Innocent Pikirayi pg 212-214, 205-208)

The Silence of Great Zimbabwe By Joost Fontein pg 35-40

The Zimbabwe culture by Innocent Pikirayi pg 215, Belief in the Past: Theoretical Approaches to the Archaeology of Religion by by David S Whitley pg 200-202

Mtoa Ruins, Hwange National Park, Zimbabwe By Gary Haynes

Heritage on the periphery by M. E. Sagiya

The Zimbabwe culture by Innocent Pikirayi pg 217-219)

The Silence of Great Zimbabwe pg 19-30

Palaces of Stone By Mike Main

Great Zimbabwe, by P. S. Garlake pg 66

Great Zimbabwe: Reclaiming a ‘Confiscated’ Past By Shadreck Chirikure pg 8-9

The Silence of Great Zimbabwe pg 5-8

Medieval Rhodesia by Randall-MacIver pg 63

The Silence of Great Zimbabwe pg 8