Textile trade and Industry in the kingdom of Kongo: 1483-1914.

the social and economic significance of Kongo's iconic raffia velvets

“In this Kingdom of Kongo they make cloths of palm-leaf as soft as velvet, some of them embroidered with velvet satin, as beautiful as any made in Italy; this is the only country in the whole of Guinea where they know how to make these cloths.”

-Duarte Pacheco Pereira, 15051

The kingdom of Kongo was one of Africa's largest textile producers prior to the colonial era. The exceptional caliber of Kongo's luxury textiles attests to the impressive technical abilities developed in the region generations before Western contact, that continued to flourish well into the 19th century.

Textiles were at once omnipresent in Kongo society and crucial in the wielding of power by its elite. From their industrial levels of production that rivalled contemporary textile producers around the world, to the sophisticated system of trade and elaborate display, Kongo's textiles were central to Kongo's social and political economy.

This article explores the history of Cloth making, trade and industry in Kongo, from its earliest documentation in the 1480s to its decline at the turn of the 20th century.

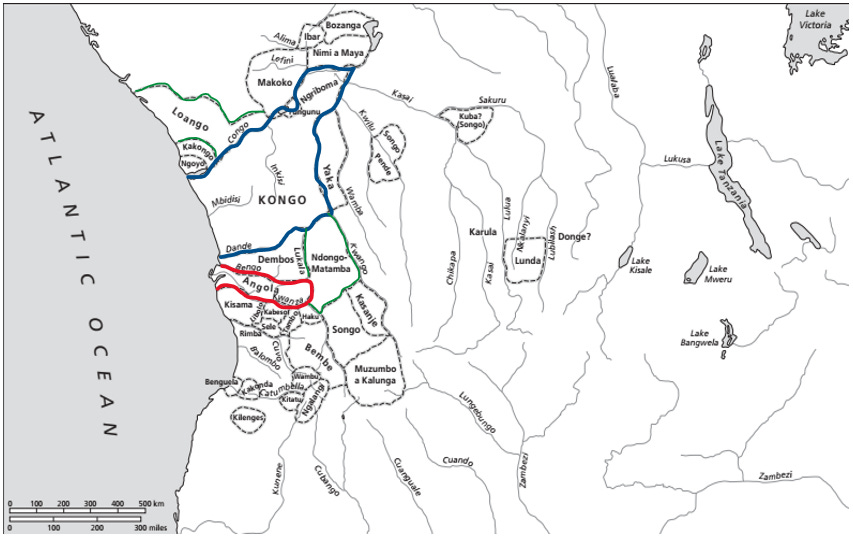

Map of west-central Africa showing the Kingdom of Kongo (in blue) and its neighbors; Portuguese-Angola (red), loango and Matamba (green)

Map showing west-central Africa’s ‘Textile belt’2

Support African History Extra by becoming a member of our Patreon community, subscribe here to read more on African history and to keep this blog free for all:

History of cloth-making in the kingdom of Kongo

The region of west central-Africa was one of the most industrious textile-producing regions on the continent. Since the late 1st millennium, cloth-making in this region relied on the manipulation of raffia threads of the palm tree which grew in the 'textile belt' extending from the mouth of the Zaire river to the western shores of lake Tanganyika. For most of west-central Africa's history, controlling parts of this textile-belt was central to the political strategies of many of the expansionist kingdoms such as Kongo. By the early 16th century, the kingdom of Kongo expanded eastwards into parts of textile producing regions, and would continue to hold them well into the 17th century.3

Unlike most of Kongo’s material culture that is relatively well preserved in archeological contexts, textiles made of plant fiber cannot survive the region’s humid tropical climate. Fortunately, Kongo’s cloth was highly regarded by European visitors who acquired it as part of diplomatic and commercial exchanges with the kingdom since the 15th century. Artifacts produced in Kongo arrived in Europe soon after the Portuguese landed at kingdom’s coast in 1483, chief among these was the intricately patterned raffia cloth made by Kongo’s weavers.

Early visitors were astonished to find an excellent variety of raffia cloth which was well-woven with many colors, featuring geometric patterns that were ornamented in high and low relief. Majority of the early chroniclers of exchanges between Kongo and Portugal, such as Rui de Pina (d. 1522), Garcia de Resende (d.1536) and Jeronimo Osorio (d. 1580) underscore the inclusion of such textiles among the gifts sent by the Kong king Joao I (1470-1509) to the Portuguese ruler Joao II.4

However, the earliest surviving Kongo textiles we have today were made slightly later in the mid 16th century, and were widely re-distributed by Kongo's Portuguese, Italian and Dutch commercial partners across western capitals as diplomatic gifts given on royal ceremonies, and as part of collections that indicated their owner's refinement and cosmopolitan inquiry. Kongo's textiles thus appear across various collections from Florence to Prague to Stockholm to Copenhagen as highly valued products whose quality was appreciated by their receivers as much as it was by the producers in Kongo.5

Corroborating earlier Portuguese accounts about the quality of Kongo’s cloth, Italian priests of the capuchin order who visisted Kongo in the early 17th century compared Kongo’s cloth with the best in their own lands, which was at the time, the best in Europe. It was in this context that an Italian visitor named Antonio Zucchelli who in 1705 reached Kongo’s province of Soyo, remarked about their textiles that “they are well woven , and well worked, as colorful as they are, they have some resemblance to the Velvet of opera, and they are strong and durable.”6

This appreciation of Kongo's textile products and the numerous descriptions of its manufacture and popularity, Indicates the importance of cloth in the kingdom's economy prior to the arrival of europeans. Long established traditions in the weaving of cloth from raffia threads are recorded in various travel accounts, and rural communities which exclusively produced and traded cloth across the region were home to some of Kongo’s most active markets.7

Kongo luxury cloth: cushion cover, 17th-18th century, Polo Museale del Lazio, Museo Preistorico Etnografico Luigi Pigorini Roma

Kongo luxury cloth: cushion cover, 18th-19th century, Nationalmuseet Prinsens Palæ

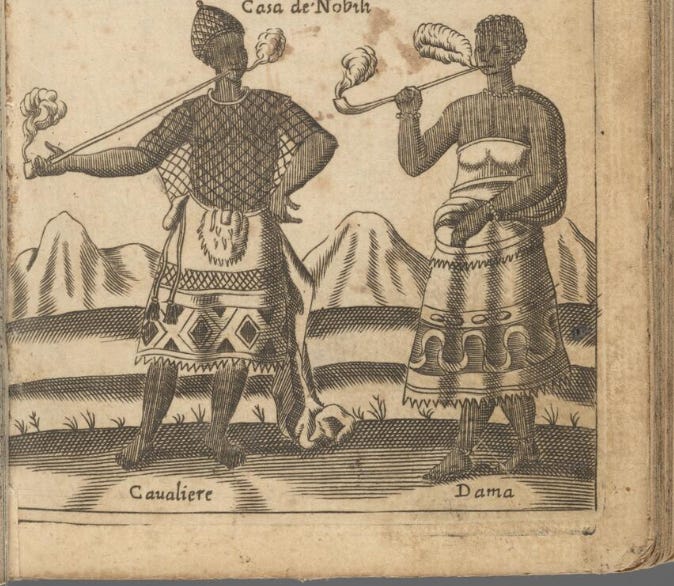

Raffia textiles were a marker of socio-political status. The quality and quantity of the cloth used for a garmet, the number of garmets and the richness of its designed all indicated their wearer's status. In Kongo, as in the neighboring kingdoms of Loango and Matamba, certain types of textiles were reserved for the king and the right top wear them could only be bestowed by him to a few favorite officials. Kongo's elite competed with each other in ostentatious display at public gatherings such as assemblies or dances.8

While most of Kongo's subjects wore plain-weave cloth as their daily dress, the elites and nobility wore a range of different luxury textiles to mark their social-political status. A unit/length of raffia cloth consisted of a single ankle-length or knee-length wrapper, requiring a few of these to make up a complete garmet for a commoner, The elites on the other hand, wore longer and more layers of these wrappers, adding many lengths to hung over the shoulder as well as a nkutu net over the chest, and a mpu cap over the head.9

Costumes for special occasions consisted of various wrappings of layers of lengthy plaited wrappers decorated with vibrant patterns and colors. According to an 18th century account, Raffia cloth was made into long coats resembling togas, velvets, brocades, satins, taffetas, damasks, sarcenets as well as bags and other accessories.10Cloth was not just used for clothing, it was also used lavishly for wall hangings and carpets/mats in houses.11

Textiles served as main currencies for Kongo's rulers and elites to build and maintain personal networks of patronage. Rulers hoarded all sorts of raffia cloth in their treasury houses along with imported cloth brought to them by European traders but originating from diverse regions, especially India. They collected plain weave cloth as tributes and fines and used it as gifts stipends to officials and clients, and they kept stores of luxury cloth to adorn their palaces and courts. "the luxury market therefore absorbed raffia products from different origins as well as overseas imports from Europe or from west Africa none of which directly replaced another"12

17th century illustration of Kongo king Garcia II (r. 1641-1661) receiving the Capuchin missionaries, by Giovanni Antonio Cavazzi

Aristocrats in the Kongo kingdom, ca. 1692, Houghton Library, Harvard University, photos by Cécile Fromont. The man is wearing a mpu cap and a nkutu cape shown below

Kongo Luxury cloth: cape (nkutu) made of natural-coloured raffia fibre, 19th century, British museum

Kongo woven fiber bag with tufted balls along top and bottom edges, 19th century, Brooklyn museum.

Kongo prestige cap, 19th century, Art institute of Chicago, Prestige cap, 19th century, Atlanta High Museum of Art, prestige cap, early 20th century, smithsonian.

In all regions of west-central Africa, raffia fabrics were associated with rites of passage and were used during rituals of birth, initiation, marriage and burial. This was best attested in Kongo's northern neighbor, the kingdom of Loango, where demand for both local luxury cloth and imported cloth grew significantly during the 18th century as a result of changing cultural practices related to elite funerals. It became customary to wrap the corpse of the ruler, patrician or rich trader in a huge bale composed of pieces of cloth (mostly raffia with a few imports) that were taken from the estate of the deceased or from funeral donations. By the 1780s, such cloth-coffins had become so big that sometimes wagons and a road had to be built to transport the shroud to its grave.13

For much of the late 15th to late 16th century, the Portuguese traders living on the island of Sao Tome and were active along Kongo's coast had seen little commercial success in insinuating themselves into the existing trading patterns since they couldn’t offer adequate products from their home country. The best they could accomplish was to reinvigorate the coastal trade in raffia cloth which they retailed in the interior region of their Angola colony where it quickly became a form of currency. They also begun importing a variety of cloth from the Mediterranean world and India that could match the quality and patterns of locally produced luxury cloths.14

By the turn of the 16th century, Portuguese traders resident in Sao Tome were buying significant quantities of Kongo's decorated cloth, and one of them who died in 1507 left an estate that included many cushions covered in Kongo's cloth.15 Soon Angola-based merchants were traveling across Kongo to the north-easternmost territories claimed by the kingdom. Kongo established customs stations along the route and charged substantial taxes on the commerce. The trade in textiles was in the hands of the long-established merchants of Kongo, and to them was added the newly arrived patrons of Angola. But production remained in the hands of local weavers in Kongo’s north-eastern provinces, and the markets for cloths were retained in these regions as well such as at Kundi and Okanga.16

18th century engraving showing the funeral process of Andris Poucouta, a Mafouk of Cabinda on the Loango coast, made by Louis de Grandpre. The coffin that carried him was at least 20 feet long by 14 feet high and 8 feet thick, the whole was transported by a wheeled wagon pulled by atleast 500 over a road built for the pourpose.

Kongo luxury cloth: cushion cover, ca. 1674, british museum

The production of Raffia cloth in Kongo.

The fiber of Raffia cloth is derived from the cuticle within the leaflets of raffia leaves. In central Africa; the trees most commonly used for raffia were the Raphia textilis welw and Raphia gentiliana De Wild. These raffia trees were native in the regions of eastern Kongo, Loango, and in the 'textile belt' region east of the Kwango river basin. The trees were cultivated in orchards, they were inheritable property and treated with the utmost care.17

The fiber is obtained by cutting the leading fresh topshoot before it unfurls its leaflets, these leaflets are then detached from the midbrib, and their skin is peeled off from the fiber within, leaving a dried fiber about 1 meter long and 3cm wide. The fibers are then processed by soaking them to make them supple before leaving them to dry, afterwhich they are converted into thread by combing them to split them apart into thin threads. Given that thinner threads produce tighter weaves, this combing process is redone multiple times until the thinnest threads can be obtained.18

weaver of cloth in Kongo, detail of a 17th century illustration by a capuchin priest, Virgili Collection (Bilioteca Estense Universitaria), photos by Cécile Fromont

The threads are then taken woven on a single heddle loom, with a fixed tension that is either vertical or oblique and set up within a permanent frame of sturdy timbers or stretched between a horizontal. Several panels of finished cloth were then sewn together to obtain textiles of a larger size. After weaving, the cloth was softened by soaking and pounding it, making it flexible enough for frequent wearing. The quality of the product was largely a result of the skill of the producer, rather than the relatively simple loom that they used.19

The luxury textiles of Kongo are technically and aesthetically distinct from those of the neighboring traditions in which the surface design is embroidered on a plain-weave. Expert weavers in Kongo transformed the knot in which the ends of interlaced strands encircle and enjoin to create a contained form. The two most prominent motifs created are endless interlacing bands and interlocked shapes, and the second is a format of rows and columns in which individual motifs float within a rectilinear frame. The interstitial columns and narrow bands that separate and surround these motifs are usually filled with refined interlaces.20

Interlacing designs and geometric motifs on Kongo’s Luxury cloth: cushion cover, Kongo kingdom, 17th-18th century, Nationalmuseet copenhagen; Prestige cap, kongo kingdom, 16th-17th century, Nationalmuseet copenhagen.

Kongo's textile motifs are also attested in other facets of Kongo's society, from its architecture to its sculptures to its cosmology. The delicately inscribed bands of geometric patterns were derived from Kongo's cosmology, in which this patterned design scheme of a continuous spiral is a visual metaphor for the path taken through time by the dead. It also appears frequently on other diplomatic gifts from Kongo to Europe, especially on the iconic side-blown ivory trumpets, the oldest of which dates to 1533, as well as on Kongo’s ceramics.21

Clockwise; Kongo ceramic bottle, early 20th century, smithsonian; Kongo basket, 19th century, smithsonian; Kongo prestige cap, 19th century, Brooklyn museum; Kongo Oliphant, 1533, Palazzo Pitti, treasury of the grand dukes.

Producers ornamented cloth according to the taste of the customers. Most surviving textiles are ornamented in a straightedged geometric style typical in general for Kongo or loango artefacts. However, illustrations from the Matamba kingdom show curvilinear arabesques (called ‘sona’) which were favored in areas east of the Kwango river, but both were made by the same weavers in eastern Kongo and the neighboring regions. 22

The different ways in which the embroidered sections reflect or absorb light relative to the plain-weave foundation of the cloth creates a rich surface of alternating textures and tonalities in a spectrum of golden hues. This natural colouring was inturn enriched by the addition of other colorants and dyes such as takula (redwood), chalk and charcoal.23

Kongo luxury cloth: cushion cover dyed with natural pigments, 17th-18th century, Pitt Rivers Museum

Cloth Industry and Trade in Kongo

While luxury raffia textiles are most commonly associated with the kingdom of Kongo, the raffia trees did not grow in the Kongo heartland. Most raffia cloth was brought from eastern Kongo and beyond, to be reworked in the core regions of Kongo for local markets within the kingdom and to external markets such as Angola, from where it was further re-exported to the interior kingdoms such as Ndongo and Matamba.

map showing the distribution of raffia trees and trade routes of cloth. (Map by Alisa LaGamma)

According to a Portuguese trader who was active in Kongo between 1578 and 1583 the inhabitants of Nsundi (one of Kongo’s northeastern provinces) “trade with neighboring countries, selling and bartering salt and textiles of various colors imported from the Indies and Portugal as well as currency shells. And they receive in exchange palm cloth and ivory and sable and marten pelts, as well as some girdles worked from palm leaves and very esteemed in these parts” 24

Kongo’s capital Mbanza Kongo imported its cloth from Mbata Malebo Pool and from 1590 onwards from Okango. Between 1575 and 1600 Luanda and the new colony of Angola generated a new demand in which the adjoining regions such as Matamba and Ndongo, took part. Before 1640 most of the supplies came overland from Mbanza Kongo, although quantities of raffia cloth were also shipped directly from Loango coast to Luanda.25

The value of a raffia textile was determined by the number of panels incorporated in the textile, the fineness of the thread indicating the number of combings the raffia fibre went through, as well as the tightness of the weave. Additionally, the value of cloth was enhanced by the decorative motifs used according to the taste of their consumers, the complexity of the execution of those decorations, and the overall level of decoration of the cloth. Therefore a more valuable piece of cloth was more labor-intensive in every aspect of its production sequence.26

Cloth production was a labor intensive process that employed many among Kongo's citizenry. A report in 1668 mentions a village in the province of Mbamba in which the men were so busy weaving that even the arrival of a missionary did not distract them. The entire production process of; extracting and processing thread, setting up the loom, weaving, sewing and tailoring was the work of adult men. Making the cloth flexible for wear and embellishing it with various designs was mostly done by women, while dyeing could be done by both groups.27

One seventeenth century Dutch account estimated that a single panel of high quality luxury cloth took about 15 to 16 days of sustained effort by a highly experienced weaver. This estimate likely included the entire process from obtaining the fiber to dyeing it, considering that the weaving process alone took less than a day. The best estimates held that one man could make 3-4 pieces of plain-weaved cloth of 50cmx50cm in one day.28

Raffia cloth was often worn for no more than 4-6 months, requiring an average of three panels/skirts per individual. Cloth was packed in oblong baskets or mutete, with one full basket weighing about thirty kilograms and constituting a headload. Luxury cloth was also carried in boxes specifically made for the pourposes.29

17th century illustration showing textile trading in the north Kwanza region (Ndongo kingdom), by Giovanni Antonio Cavazzi. the patterned cloth is made of raffia/palm fiber and is carried in a rectangular basket like this one below.

Kongo container measuring 56x35cm, 18th century, Art Institute of Chicago

The available contemporary sources both about the quantities and value of cloth traded stem from Angola. A fiscal official in Luanda named Pero Sardinha twice informed the council of state in Lisbon about this matter in the year 1611 and 1612. He listed the average quantities of cloth coming into Luanda city annually as follows: From Kongo: 12, 500 painted cloths at 640 reis each; 45,000 songa (ie from Songo east of Okanga) cloths at 200 reis each; 35,000 half cundi (ie: from Kundi in Okanga) cloths at 100 reis each. From Loango: 15,000 exfula (mfula) cloth at 200 reis each and 333 ensaca (nsaka) cloth at 1200 reis each.30

Converting this into meters yields 25,038 meters for Loango and 114,400 meters for Kongo. These quantities did not constitute total production or trade from Kongo, but just the legal trade alone from a specific region of Kongo known as Momboares that managed to pass through the customs houses in Lunda.31 These are significant figures and suggest that the huge quantities of cloth testity that for the Portuguese, commerce in raffia was more profitable than the slave trade until 1640, even though both were attimes complementary.32

Cloth trade between Kongo and Angola was disrupted during the kingdom's military alliance with the Dutch against Portugual and the brief expulsion of the latter from Luanda in 1641. But by 1649, the Portuguese returned to Luanda and Angola came to rely less on its cloth trade with Kongo, choosing to import their cloth from the kingdom of Loango. Additionally, the Portuguese took over the Nzimbu shell mines of Luanda, undercutting Kongo's monopoly over the popular currency and forcing the kingdom to use alternative currencies. Kongo would thereafter promote the use of raffia cloth in its kingdom as currency, joining the rest of west-central African kingdoms that had already been doing the same.33

In 17th century Kongo, raffia cloth was in such demand that lengths of plain weave were used as currency in northern and eastern Kongo, on the loango coast and also in Angola where it was adopted by the Portuguese. Textiles were measured by the number of leaves they comprised, which were standardized into sizes of 52x52cm in Kongo and elsewhere. The value was calculated based on the number of lengths per cloth, the type of ornamentation and the tightness of the weave. This textile 'money' was carried in single lengths or in books of lengths sown together at a corner. It was soon adopted by European traders such as the Portuguese in Angola and the Dutch on Loango's coast.34

Raffia cloth was currency with an intrinsic exchange value being equal to its use value, it was a self regulating currency that could maintain its value through being in common usage even without strict regulation.35 While it was used in purchasing most goods and services in Kongo and settle dues of any kind of disputes, it was not used for in other markets such as labour, land and construction. An estimated 90% of the cloth produced was used as clothing, with only a small fraction of it circulating or hoarded as currency. Kongo's cloth was therefore inflation proof, given its use as both a currency and a consumer good.36

Cloth production in Kongo had reached proto-industrial levels in the 17th century. A considerable amount of cloth from Momboares was also exported to Loango where some 700 meters of cloth were included in the Loango King’s burial hoard in 1624. Other cloth went to the southern and central parts of Kongo, and to neighbors like Matamba and beyond. Total production of Momboares is estimated to have exceeded 300-400,000 meters a year, an impressive figure given that its population density was just 3.5 people per sqkm. This easily rivals contemporary European textile producing regions like Leiden (Netherlands) which had a similar population density but produced less.37

Strictly speaking however, production was not organized in the form of a modern industry since capital wasn’t invested in the acquisition of equipment nor in obtaining the raw raffia, as both often involved the use of subsistence or family labor. Nevertheless, early modern textile industries like in Leiden utilized both urban and rural labor in a way that wasn’t too dissimilar Kongo textile workers that could be found both in the capitals and in the villages. Kongo’s political adminsitration had a remarkably efficient capacity to transfer large quantities of cloth produced beyond immediate needs, and concentrate it at central points such as political capitals, where it was used to pay tributes, tolls and fines.38

Stagnation and decline of Kongo’s cloth-making industry.

In the mid-17th century, Kongo begun to lose some of the customers of its cloth such as the Portuguese of Angola. After 1648 a new route from Luanda to the cloth market of Okanga in the Kwango river basin was developed which completely bypassed the heartland of Kongo to the east and which also provided the then flourishing capitals of Matamba and Cassange further southeast with raffia cloth. While this trade expanded overall cloth production in the region, it partially reduced Kongo's role as the middle-man in reworking the cloth for export.39

Internal process in the kingdom which culminated in the civil wars of the late 17th century doubtlessly affected the laborious industry of cloth-making and is unlikely to have been fully restored to its pre-civil war levels when the kingdom re-united in 1709. Coincidentally, as Loango displaced Kongo in the late 17th century, alternative sources of luxury cloth such as Indian textiles were increasingly imported from European traders at the coast due to an uptick in slave trade in the northern coast beyond Kongo. Indian cloth had for long been incoporated into Kongo's local textile markets for its variety of designs and colors that resembled Kongo's own designs, in contrast to European cloth. While these Indian textiles never displaced Kongo's textiles, the kingdom's stagnation opened is markets to more varieties of cloth that Kongo's own traders were now selling in increasing quantities across the region.40

18th century painting of a capuchin missionary blessing a wedding, Bernardino d’Asti, Biblioteca Civica Centrale, Turin. The Kongo elites are shown wearing a mix of imported and local clothing.

Kongo’s access to Angola’s cloth market was likely restored in the mid 18th-century, As late as 1769, a report from Luanda noted that the ordinary money in Angola was “cloths of straw made in Kongo,” and nzimbu shells, that were used by every merchant after a failed attempt by the colonial government to introduce copper coinage in 1694 had collapsed within less than a year. Despite the decline of Kongo and the increased importation of foreign cloth, the very gradual shift of displacing locally produced textiles with foreign cloth didn’t begin until the mid-19th century when steamships from Europe began making regular stops in Africa, and for the first time in history it was possible to ship bulk commodities cheaply.41

Contemporaneous advances in European and American manufacturing technology allowed for the mass production of brightly coloured and patterned cotton cloth. While the quality of these cotton cloths was generally accepted to be low by African consumers, the range of colors and styles allowed for greater personal expression. The so-called 'Manchester cloth' and European imitations of Indian cloth, steadily replaced the finer imported Indian cloth of the earlier centuries as well as the locally made luxury cloth, beginning in the coastal region and very slowly advancing into the interior.42

But even by the last quarter of the 19th century -and despite the now widespread use of cloth imported from Europe, local raffia cloth was still brought from the interior to the coastal area of Kongo and Angola. Accounts from the 1880s to the first decade of the 20th century still contain frequent mentions of a lively trade in local cloth in the Kongo heartlands such as at the market of Kilembela, just northeast of Kongo’s capital. A visitor to Kongo’s capital in 1879, observed that only a handful of men were dressed in European cloth, while the rest still wore locally produced textiles, and it would take another decade of bulk commodity trade for this to change significantly.43

Photographs of royal coronations as late as 1911 show Kongo’s rulers still wearing a combination of local and imported textiles, symbolizing the convergence of old and new customs.44 It was only when the Kongo kingdom was disrupted by political unrest and collapsed in 1914, that the highly elaborate weaving know-how, considered one of the Kongo kingdom’s trademarks both in Africa and Europe, vanished.

When Europe was engulfed in one of the history’s deadliest conflicts in the early 17th century, the African kingdoms of Kongo and Ndongo took advantage of the European rivaries to settle their own feud with the Portuguese colonialists in Angola. Kongo’s envoys traveled to the Netherlands, forged military alliances with the Dutch and halted Portugal’s colonial advance. Read more about this in my recent Patreon post:

Esmeraldo de Situ Orbis by Duarte Pacheco Pereira pg 144

Maps by J.K.Thornton

A History of West Central Africa to 1850 by John Thornton pg 63-64, 140-142)

Kongo: Power and Majesty by Alisa LaGamma pg 135

Kongo: Power and Majesty by Alisa LaGamma pg 137-158)

Relazioni del viaggio, e missione di Congo nell' Etiopia inferiore occidentale by Antonio Zucchelli pg 149

African art and artefacts in european collections by Ezio Bassani and M.D. Mcleod)

Raffia Cloth in West Central Africa, 1500–1800 by Jan Vansina

The Kongo Kingdom by Koen Bostoen, Inge Brinkman pg 175)

Raffia Cloth in West Central Africa, 1500–1800 by Jan Vansina pg 266-267)

A History of West Central Africa to 1850 by John Thornton pg 12

Raffia Cloth in West Central Africa, 1500–1800 by Jan Vansina

Power, Cloth and Currency on the Loango Coast by Phyllis M. Martin pg 5-7

Portugal and Africa By D. Birmingham pg 40-41, A History of West Central Africa to 1850 by John Thornton pg 94

Raffia Cloth in West Central Africa, 1500–1800 by Jan Vansina pg 264, Kongo: Power and Majesty by Alisa LaGamma pg 135)

A History of West Central Africa to 1850 by John Thornton pg 94-95

Raffia Cloth in West Central Africa, 1500–1800 by Jan Vansina pg 274, Power, Cloth and Currency on the Loango Coast by Phyllis M. Martin pg 1-2

Raffia Cloth in West Central Africa, 1500–1800 by Jan Vansina pg 265-7).

The Kongo Kingdom by Koen Bostoen, Inge Brinkman pg 171, A History of West Central Africa to 1850 by John Thornton pg 13

Kongo: Power and Majesty by Alisa LaGamma pg 135)

The Kongo Kingdom by Koen Bostoen, Inge Brinkman pg 171, Kongo: Power and Majesty by Alisa LaGamma pg 133, 138)

Raffia Cloth in West Central Africa, 1500–1800 by Jan Vansina

Power, Cloth and Currency on the Loango Coast by Phyllis M. Martin pg 2

The Kongo Kingdom by Koen Bostoen, Inge Brinkman pg 149

The Kongo Kingdom by Koen Bostoen, Inge Brinkman pg 174

The Kongo Kingdom by Koen Bostoen, Inge Brinkman pg 175)

Precolonial African Industry and the Atlantic Trade, 1500-1800 by John Thornton pg 14

Kongo: Power and Majesty by Alisa LaGamma pg 135)

Raffia Cloth in West Central Africa, 1500–1800 by Jan Vansina

Raffia Cloth in West Central Africa, 1500–1800 by Jan Vansina

Precolonial African Industry and the Atlantic Trade, 1500-1800 by John Thornton pg 12, Raffia Cloth in West Central Africa, 1500–1800 by Jan Vansina

The Kongo Kingdom by Koen Bostoen, Inge Brinkman pg 174)

Portugal and Africa By D. Birmingham pg 59-60)

Raffia Cloth in West Central Africa, 1500–1800 by Jan Vansina, Power, Cloth and Currency on the Loango Coast by Phyllis M. Martin pg 4

Power, Cloth and Currency on the Loango Coast by Phyllis M. Martin pg 4

Raffia Cloth in West Central Africa, 1500–1800 by Jan Vansina

Precolonial African Industry and the Atlantic Trade, 1500-1800 by John Thornton pg 13-14

Raffia Cloth in West Central Africa, 1500–1800 by Jan Vansina pg 280-281)

Raffia Cloth in West Central Africa, 1500–1800 by Jan Vansina

Precolonial African Industry and the Atlantic Trade, 1500-1800 by John Thornton pg 18, The Kongo Kingdom by Koen Bostoen, Inge Brinkman pg 242-243, for a similar process in Loango, see Power, Cloth and Currency on the Loango Coast by Phyllis M. Martin pg 7-9

A History of West Central Africa to 1850 by John Thornton pg 290, 351

Interpretations of Central African Taste in European Trade Cloth of the 1890s by James Green pg 82)

Kongo in the Age of Empire, 1860–1913 by Jelmer Vos pg 47, 54

Kongo in the Age of Empire, 1860–1913 by Jelmer Vos pg 106