The Art of Power in central Africa: the political and artistic history of the Kuba kingdom (1620-1900)

an iconography of authority.

Central Africa in the 17th century witnessed the efflorescence of one of the continent's most elaborate artistic traditions. Nestled on the edge of the Congo rainforest, the Kuba kingdom developed a sophisticated political and judicial system controlled by a hierarchy of title holders, whose status was defined by their corresponding series of prerogatives, insignia and emblems that were displayed in artworks which they commissioned.

The Kuba are renown in central Africa for their dynamic artistic legacy that was attested across a broadly diverse array of media, a product of the complexity of Kuba's political organization which facilitated a remarkable artistic tradition where artists visualized their patrons' power. The spectrum of Kuba's decorative arts, from intricate wood carvings to cast-metal and velvet-textured cloth, are the legacy of the versatility and skill of Kuba's artists.

This article explores the history of the Kuba kingdom, and the relationship between political authority in the kingdom with its celebrated art traditions.

Support AfricanHistoryExtra by becoming a member of our Patreon community, subscribe here to read more about African history, download free books, and keep this newsletter free for all:

Kuba from the 17th-18th century.

The Kuba kingdom's establishment in the early 17th century was preceded by the movement of the Bushong-speakers who originally lived north of the Sankuru river but migrated south, and gradually incorporated autochtonous groups to create the first chiefdoms. The strongest these, the Bushong and Pyang, Bieeng, and Ngeende eventually subsumed the others, and began a struggle for ritual and political supremacy which culminated with the ascension of Shyaam aMbul aNgoong, who in 1625, defeated the Pyang, and founded the Kuba kingdom as its first king at the capital Nsheng. Over the succeeding centuries, internal dynamics within the multi-ethnic kingdom led to thee innovation of complex administrative and judicial institutions out of pre-existing political systems in the region.1

Shyaam introduced several innovations that he borrowed from neighboring groups, he is credited with establishing a bureaucratic capital, a patrician class of titled office holders, and an elaborate complex of royal symbols and pageantry; although these innovations were likely developed later but were only credited to him as the founder.2 Shyaam's successors, especially king Mboong a Leeng and king Mbo Mboosh whose cumulative reign spanned much of the 17th century, greatly expanded Kuba's territories westwards, concentrating defeated foes within the capital, and consolidating their power by reducing the authority of provincial chiefs. 3

Over the course of the 18th century, Kuba's Kings, mostly notably Kota Mbweeky, Kot aNce and Mbo Pelyeeng aNcé, expanded Kuba southwards for control of the copper-trading routes and the kingdom attained its maximum extent. These kings transformed Kuba's institutions, especially Mbo Pelyeeng aNcé who abolished local cults who represented the different ethnic and lineage groups within the kingdom, in favour of more regional nature cults that represented the kingdom itself. Such was the memory of this that his name was during the early colonial era translated by the Kuba as "God" although not possessing the equivalent monotheistic characteristics of the Christian deity.4

The government of Kuba in the 19th century

Kuba's political structure was characterized by the division and balance of power, with court dignitaries organized in councils that constituted a body which counter-balanced the power of the King. The king shared power with councils the most significant of these was the ishyaaml, which was comprised of around 18 senior titleholders and provincial chiefs that together represented the aristocratic Bushong clans and thus the whole kingdom, this council was in charge of "electing" the King from his matrilineage of potential candidates, it also had the authority on decisions of war and peace, and could veto the king’s orders and edicts. Below this was the Nsheng-based council ; the mbok ilaam, it was in charge of day-to-day administration and the provincial administration, and it was presided over by the King, the titleholders at the capital, and senior military.5

Below the king and councils was a bureaucracy of senior title-holders. There were over 120 distinct titles within the capital and from whom most of the members of the councils were chosen. Their positions were not hereditary as most were selected from candidates elected by their peers. Below these was the provincial administration with subordinate chiefs with similar councils comprised of elected titleholders (county headmen), this provincial administration sent tribute to the capital which was handled by an official , provided labour for crafts manufactures and construction at the capital, and military levies for the army6. “The degree to which the whole Bushong population was represented in this government was perhaps its most remarkable feature. All the titleholders were elected by their peers in council without any royal input, so that the whole council truly represented the population of the capital and the free Bushong villages.”7

Kuba in the 19th century, showing the core of the kingdom (dominated by the Bushong), and the provinces it controls.

These chiefs also reported to the capital annually at a major festival, and the whole lattice of administration from the king to the councils and provincial chiefs largely derived their income from tributes (agricultural produce, cowries, tradable goods) and revenue collected from the courts (fees and fines paid in cowries).8 The judicial system consisted of provincial courts and the main court at the capital , and both of these were comprised of senior title holders who were selected depending on the individuals involved and the type of crime. Appeals could be lodged from the provicial level to the capital and to the highest council that sat with the king, but the fees/fines increased with each level, with lesser crimes handled by lower courts while capital offences were handled by the King's coucil. In all cases, compensation in the form of fees and fines went to the state, which therefore incentivized it to enforce peace using a police force, and incentivized the Kuba citizens to became minor titleholders, of which atleast a quarter of adult males were in the late 19th century.9

Kuba's markets were strictly regulated with a representative of the king overseeing law and order, a royal taxcollector who took in sales taxes, and trade disputes were settled by a court on the spot. Transitions were settled not just in cash (cowries) but also on credit and by pawning, the latter forms of exchange often occurred between professional traders who were also engaged in long distance regional trade within the kasai region and to routes that terminated in Luanda. Besides the items traded domestically and regionally including cloth, agricultural products, iron and salt, the Kuba exported cloth, red camwood, Ivory and rubber, that were sold across regional and global markets in exchange for copper and brass, cowrie shells and other commodities.10

At its height between the late 17th to mid-19th century, the kingdom's growing population, increased production and expanding trade created a demand for the services of skilled artisans whose products constituted markers of social differentiation. Under the patronage of Kuba's title-holding elites, professional classes of weavers, embroiderers, carvers, and metalsmiths flourished as they innovated and invented new artistic styles to create a variety of functional and ornate works including richly embroidered cloth and intricately carved sculptures made of copper-alloys, iron and wood.11

“Kuba’s bureaucratic system had the interesting side effect of interesting most men in the operation of the administration and in generating enthusiastic acceptance of the regime.... The system allowed the Kuba to become intoxicated with organization and above all with public honors, insignia, and pageantry..."12

Nsheng became a vibrant center of decorative arts in the region. kuba's Kings commissioned artists to create numerous miniature sculptures in their likeness (ndop) which given their fairly standardized figurative convention with the Kuba's royal regalia, is given a personalized signifier (ibol), the kings also commissioned drums of office (pelambish), and individualized geometric patterns that were to be depicted on Kuba's textiles (although most patterns were created by the artists themselves). Decorative design (bwiin) was the very essence of Kuba's artistic activity and particular design forms, which comprise a corpus of about 200 distinct patterns, were often named after their inventors.13

Ndop figure of king Mbó Mbóosh with drum ibol ca. 1650, Brooklyn museum: 61.33, Ndop figure of king shyaam aMbul aNgoong with a game-board ibol, c. 1630, british museum af 1909, 1210.1

Ndop figure of king Mbo pelyeeng aNce with an avil ibol, ca. 1765, British museum: Af1909,0513.1. Ndop figure of Kot aNce with a drum ibol, ca 1785, royal museum for central africa : EO.0.0.1525614

Kuba Art; Textile and sculpture

Kuba artists manipulated the contrast of four basic properties of; color, line, texture, and symmetrical arrangements of motifs in order to produce a consistent design system which is found on textiles, cast metal, and wood carvings. In the Kuba kingdom, as in much of west-central Africa, possession of large collection of high quality, richly embroidered cloth was considered a symbol of power and the drive for prestige between the titled holders resulted in the amassment of textiles. The most elaborately patterned cloths were worn during important public ceremonials, hang up in homes as wall cloths, they were used to wrap the dead, they were sold across the region's vast textile trade network, were used as currency, and given as tribute.15

Kuba cloths are made by stripping white raffia-fibers which are then separated, combed, warped, and weaved on a heddle loom by men, while the women took over the patterning, dyeing and embroidering of the cloth, using low pile plush to produce a tight weave and join many stitches to create raised motifs. The usual colour range included Red, yellow, black and white; with the red dye obtained from camwood; the yellow dye from the brimstone tree, the black dye from charcoal and the white dye from kaolin.16

textiles, 19th century, British museum, Af1999,07.9, Af1999,07.8

Textiles, 19th-20th century, Brooklyn museum, 22.1523, 1989.11.6, 1989.11.7

The raffia palm tree (raphia textilis welw) from which these textiles were obtained was a central item in Kuba's crafts-making; "They found a use for absolutely every part of the tree, be it for construction, for roofing, for crafting furniture, as strong string for sewing, as tinder, and even as a medium from which to harvest edible grubs"17

Kuba house under construction, 1920s, boston museum

The tree was especially appreciated for its wine, which was the most popular beverage drunk at social gatherings and on other occasions. Intricately carved palm wine cups were a high prestige item among the Kuba and those carved in the anthropomorphic forms and inscribed with elaborate geometric designs were often owned by Kuba's title-holders.18

anthropomorphic wooden cup depicting a figure whose hairstyle is associated with royalty, 19th century, brooklyn museum, 56.6.37

anthropomorphic cups made of wood decorated with copper, 19th century, Brooklyn museum 22.1487, British museum; Af1949,46.399, Af1949,46.397

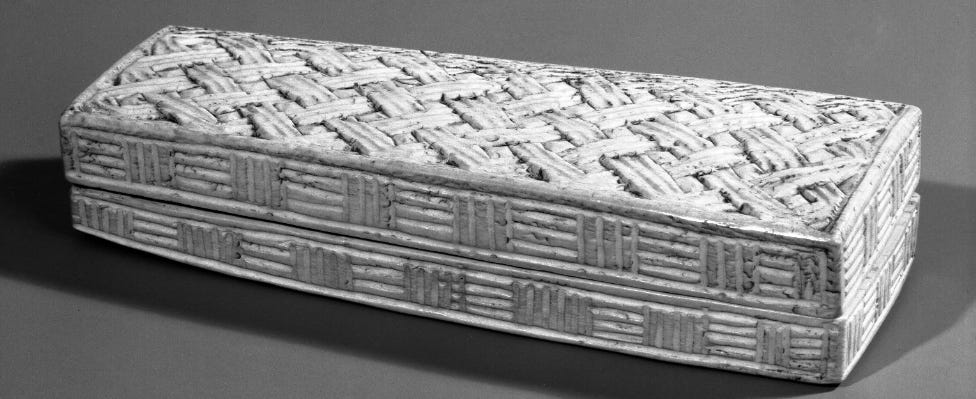

Among other carved artworks were the cosmetic boxes whose skillful carving with anthropomorphic features, classic Kuba patterns and an deceitful imitation of other objects illustrate the Kuba desire for prestige. These crescent-shaped and cylindrical-shaped carved boxes held a red powder called twool which was obtained by grating the wood of pterocarpus soyauxii, it was used to anoint the body and thought to enhance its vitality. This powder was acquired through Kuba cloth's trade with its northern neighboring groups.19

Besides the textiles and carvings, the Kuba were excellent smiths who made a variety of cast metalworks with functional and artistic aspects. The majority of the corpus includes a broad range of Kuba swords that are often classified as combat swords or ceremonial swords (but with considerable overlap between them) All types of swords are primarily comprised of iron blades that are often embellished with incised patterning, while the hilts are made with copper alloys, and carved wood, both of which feature intricately inlaid patterns found across other Kuba visual mediums.20

carved wood cosmetic boxes with anthropomorphic features and geometric patterns, 19th century, British museum, Af1913,0520.6, Af1908,Ty.7.a

carved ivory cosmetic box, 19th century, Brooklyn museum, 74.33.4a-b

carved wood drum and drinking horn, 19th century, British museum, Af1909,0513.265

Ceremonial swords made of iron, copper, wood, brass, 19th century, british museum, Af1909,0513.191

Epilogue

The Kuba kingdom had never been invaded since its establishment in the 17th century and the robustness of its government, which greatly regulated and restricted the movements of ivory traders in the late 19th century but profited from the trade, attracted the attention of the Belgian King Leopold's colonial agents during his brutal conquest of what would later become the Congo colony. In 1899 and 1900, three invasion forces routed the army of the Kuba, the first in a surprise attack, the second with a trap of title holders that were then massacred and and the last sacked the capital Nsheng. 21

Despite this destruction, the Kuba title-holders restored a semblance of order once they were reinstalled after a major rebellion in 1904-5 during the chaotic early colonial era, and the Kuba artists’ celebrated artistic traditions continued largely unadulterated, preserving the kingdom's three centuries old legacy of Power through its Art.

Students at the Nsheng art school in 1973, D.R.C

The city of TIMBUKTU was once one of the intellectual capitals of medieval Africa. Read about its complete history on Patreon;

from its oldest iron age settlement in 500BC until its occupation by the French in 1893. Included are its landmarks, its scholarly families, its economic history and its intellectual production.

If you liked this Article and would like to contribute to my African History website project, please donate to my paypal

Paths in the Rainforests by Jan Vansina pg 123, 230, Kuba Chronology Revisited by Jan Vansina pg 134-135 )

Heroic Africans: Legendary Leaders, Iconic Sculptures by Alisa LaGamma pg 164

A History of West Central Africa to 1850 byJohn K. Thornton pg 215-216, Kuba Chronology Revisited by Jan Vansina pg 143

A History of West Central Africa to 1850 byJohn K. Thornton pg 236, The history of god among the kuba pg 35-36)

Kuba Chronology Revisited by Jan Vansina pg 135, The Early State by H. J Claessen pg 367, 371-372)

The Early State by H. J Claessen pg 370-371

Being Colonized: The Kuba Experience in Rural Congo by Jan Vansina pg 46

The Early State by H. J Claessen pg 368)

The Early State by H. J Claessen pg 373-374)

The Early State by H. J Claessen pg 363-364, 376)

Heroic Africans: Legendary Leaders, Iconic Sculptures by Alisa LaGamma pg 156)

The Children of Woot by Jan Vansina pg 132

Heroic Africans: Legendary Leaders, Iconic Sculptures by Alisa LaGamma pg 161-163)

Heroic Africans: Legendary Leaders, Iconic Sculptures by Alisa LaGamma pg 166

Design Categories on Bakuba Raffia Cloth by DK Washburn pg 11)

Design Categories on Bakuba Raffia Cloth by DK Washburn pg 23, African Textiles by John Picton pg 39)

Being Colonized: The Kuba Experience in Rural Congo, 1880–1960 By Jan Vansina pg 121

Art of central Africa by Hans-joachim Koloss pg 48

The Doyle Collection of African Art by Sarah Brett-Smith pg 13

African Arms and Armour by Spring Christopher pg 144, Collecting African Art: 1890s-1950s by Christa Clarke pg 46

Being Colonized: The Kuba Experience in Rural Congo, 1880–1960 By Jan Vansina pg 69-85)

“Decorative design (bwiin) was the very essence of Kuba's artistic activity and particular design forms, which comprise a corpus of about 200 distinct patterns, were often named after their inventors.”

I love how the Kubq were protecting the “IP” of artists if you will. I hope I’ve interpreted that correctly? The level of organization in every aspect of the kingdom is just amazing!

Legacy is the right framing. I like that. Thank you.