The creation of an African lingua franca: the Hausa trading diaspora in West Africa. (1700-1900)

Trade networks beyond ethnicity.

Africa is a continent of extreme linguistic diversity. The continents’ multiplicity of languages and ethnicities, created a cultural labyrinth whose dynamic networks of interaction encouraged the proliferation of diasporic communities which enhanced cross-cultural exchanges and trade, from which common languages (lingua franca) such as Hausa emerged; a language that is used by over 60 million people and is one of Africa’s most spoken languages.

Hausa is a linguistic rather than ethnic term that refers to people who speak Hausa by birth.1 The notion of ethnicity itself has been subjected to considerable debate in African studies, most of which are now critical of cultural approaches to ethnicity that interpret through the lens of the interaction between firmly bounded ‘races’, ‘tribes’, or ‘ethnic groups’2. Ethnicity is a social-cultural construct determined by specific historical circumstances, it is fluid, multilayered, and evolutionary, and its denoted by cultural markers such as ‘who one is’ at any one moment in time; also ‘what one does’.3 The Hausa’s relatively inclusivist culture, and their participation in long distance trade, enabled the creation of diasporic communities and subsequently, the spread of the Hausa language as a lingua franca across much of west Africa.

This article sketches the history the Hausa diaspora’s expansion in West Africa, and looks at the role of long distance trade in the emergence of Hausa as a lingua franca

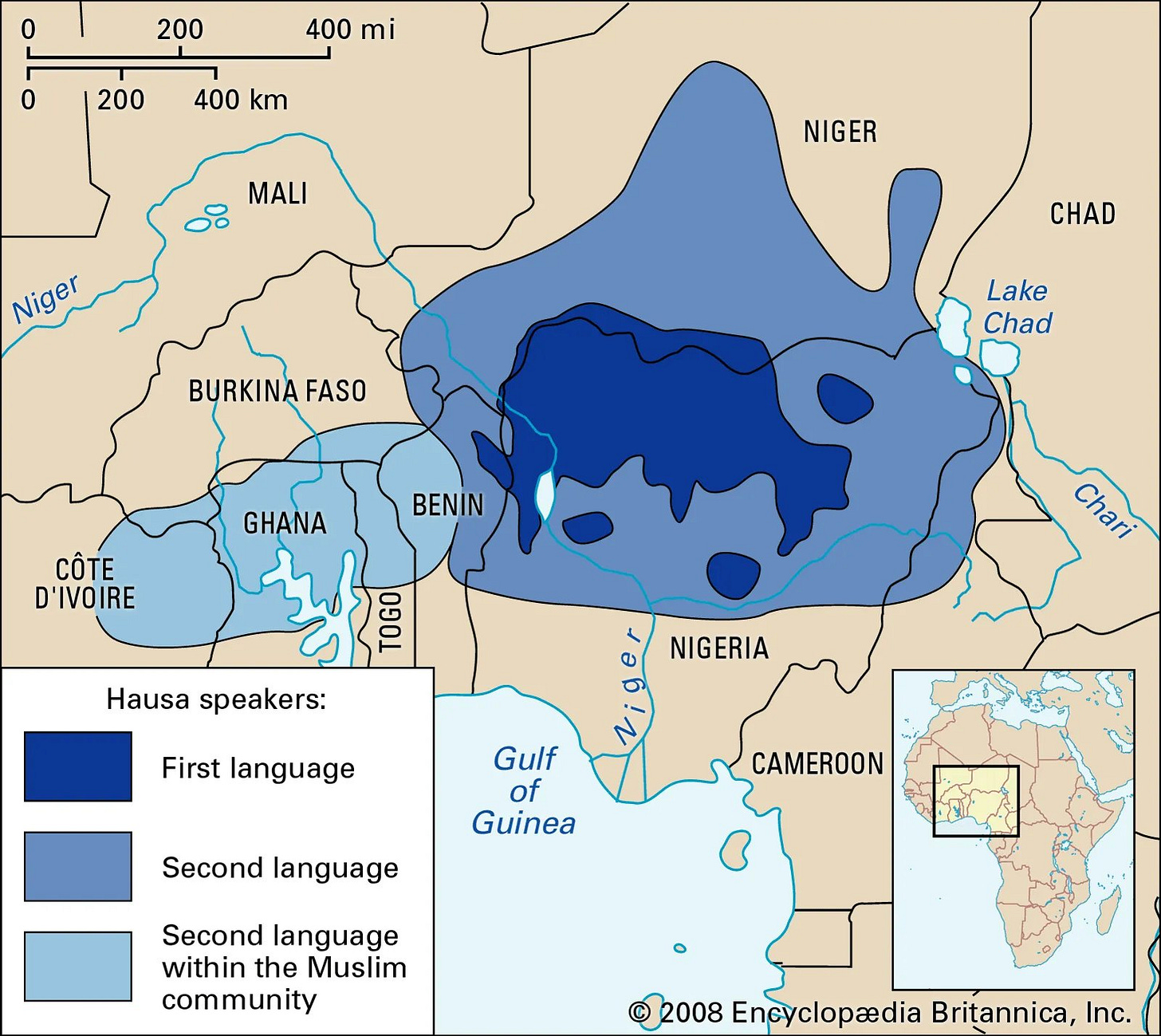

Map of west Africa showing the geographical extent of the Hausa language

Support AfricanHistoryExtra by becoming a member of our Patreon community, subscribe here to read more about African history, download free books, and keep this newsletter free for all:

Brief background on Hausa society

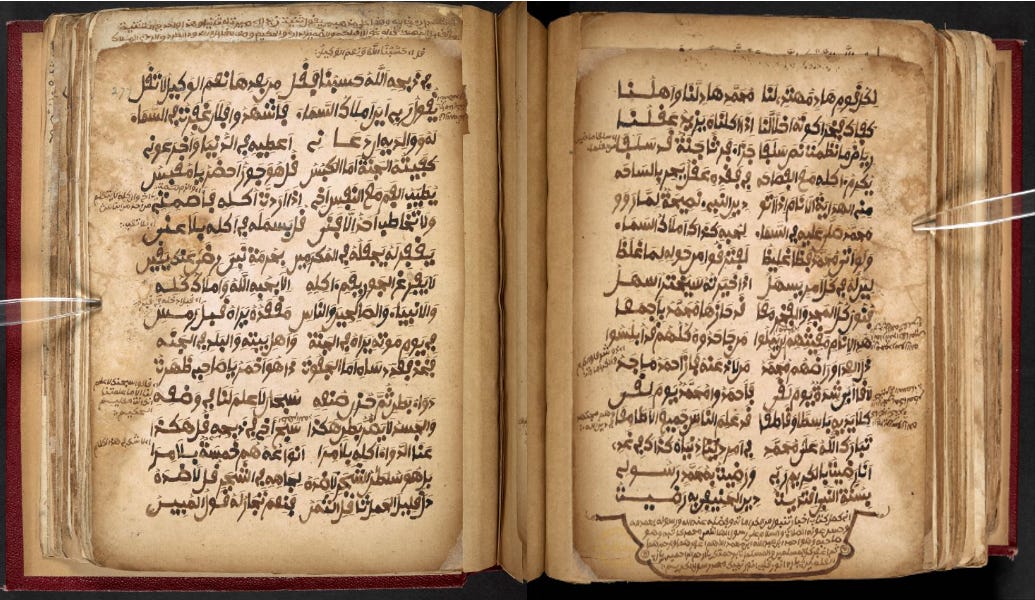

The main internal sources dealing with early Hausa history include several 19th century chronicles such as, the Kano Chronicle, the Daura Chronicle, Wakar Bagauda, Mawsufat al-sudan and ‘Rawdat al-afkar’ (by Sokoto scholar Dan Tafa), and the description of Hausalands (by Hausa scholar Umar al-Kanawi). All contain the political myth of origin of the Hausa states, which sought to describe the emergence, installation and modification of political systems and dynasties alongside other innovations including religion, trade and architecture, they also include the arrival of separate groups of immigrants from the west (Wangara); east (Kanuri); north (Berber/Arab); and south (Jukun), and their acculturation to the Hausa societies.4

The Kano chronicle relates a fairly detailed account of the history of Kano and a few of the Hausa city-states through each reign of the Kano kings from the 10th to the 19th century.5 The Daura chronicle, Wakar Bagauda, Umar’s description of the Hausalands, and Dan Tafa’s works also include these meta-stories of origin that relate to how the different city-states were established and combine themes of autochthony and foreignness.6

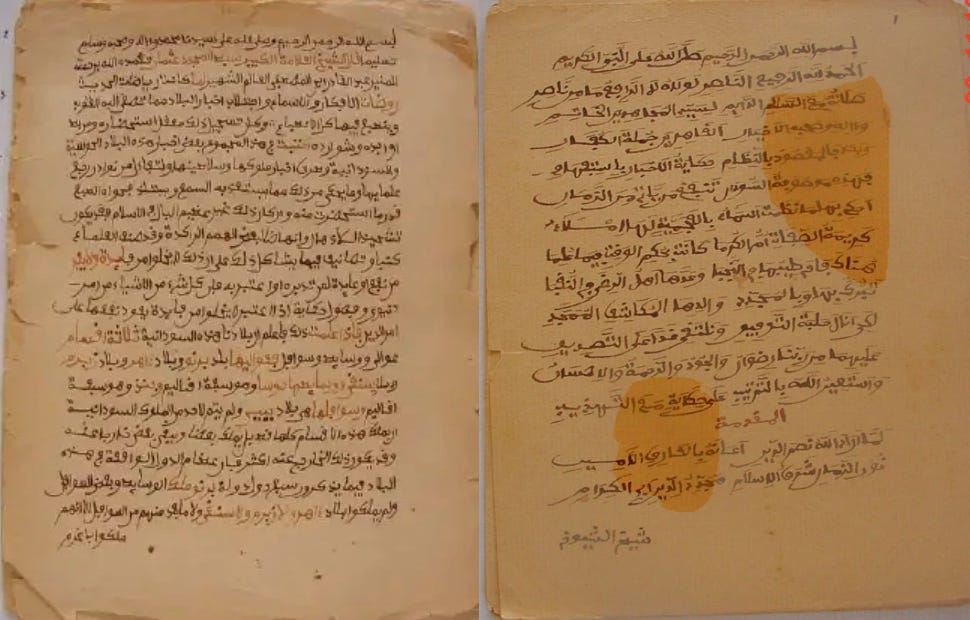

‘Rawdat al-afkar’ (The Sweet Meadows of Contemplation) written in 1824; and ‘Mawsufat al-sudan’ (Description of the black lands) written in 1864; by the west african Historian/Geographer/Philosopher Dan Tafa. (read more about Dan Tafa here and see Umar’s works here)

Hausa linguistic history: From Afro-Asiatic to Chadic.

Hausa historiography also relies on linguistics to shed light on the early history of the Hausa, through the reconstruction of linguistic borrowings from the neighboring languages (especially Kanuri), provides important insights into social and cultural histories of the region. 7

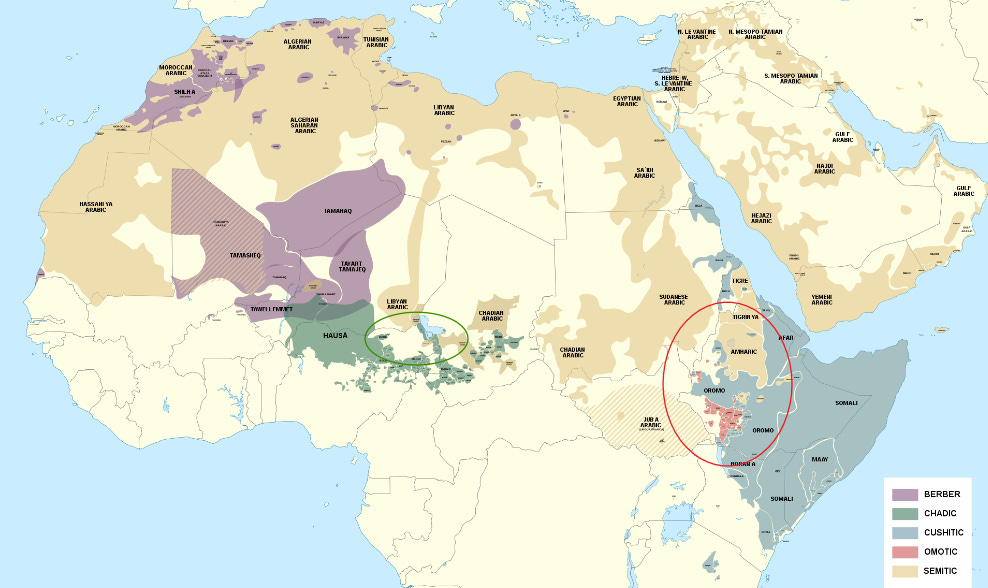

Hausa belongs to the Chadic branch of languages within the larger Afro-Asiatic group of languages (other branches within Afro-asiatic include Semitic languages such as Aramaic, Arabic and Tigrinya, as well as 'Cushitic' languages such as Beja). After the split-up of the Proto-Afroasiatic group, the ancestral core of Chadic spread westwards across the Lake Chad basin around 6,000BP.8

Historically Chadic languages were spoken in the regions west and south of Lake chad (in what is now northwest Nigeria and Chad), and over time some were replaced by Hausa in the west, and by Kanuri and to the east. From its core in the western shores of lake chad, Hausa spread west into what is now north-western Nigeria and southern Niger, and then to the south east into what is now central Nigeria across the early second millennium in the region that is referred to as the Hausalands. The relatively minor dialectical differences among Hausa speakers across west Africa outside the Hausalands “core”, indicates the language's relatively recent expansion over the last three centuries.9

Map of Afro-Asiatic languages showing the ‘ancestral afro-asiatic core’ about 10-15,000BP (in western Ethiopia), and the ‘ancestral chadic core’ around 6,000BP (in the lake chad region)

"Hausa" is itself an exonymous term as the Hausa referred to themselves by the city-states where they hailed (eg Kanawa from Kano, Gobirawa from Gobir, Katsinawa from Katsina, etc). The term ‘Hausa’ first appears in the extant literature in the 17th century as a result of the interaction of two major west African trading networks that separated the Wangara (who dominated the region west of the Niger river), from the region east of the Niger river; which was dominated by a languages that the Wangara referred to as Hausa.10 The trading towns of the Hausaland were cosmopolitan and their rulers, residents, merchants and other itinerant groups spoke Hausa as well as their local language.

Political history of the Hausa states and ‘Hausaization’.

The political systems of the Hausa city-states were informed by a high degree of syncretism and internal heterogeneity, the governance structure took on a form of contrapuntal paramountcy involving power-sharing between the traditional groups (often located in the countryside) and Muslim groups (located in the cities).11

In order to foster their political interests and promote royal cults, Hausa rulers implemented liberal immigration policies that encouraged people from various parts of west Africa and north Africa to move into the cities, a process which ultimately contributed to the incorporation of diverse groups into Hausa ethnicity12. The interplay between the city and the countryside, with its religious implications, is central to Hausa culture and social structures and the construction of Hausa identity (Hausaization).13

Areal view of Kano in 1930 (cc: Walter Mittelholzer), showing the contrast between the walled city (in the foreground) and the countryside (background)

Hausaization was a cultural and ecological process in which the Hausalands and Hausa states developed a distinct Hausa identity; it appears as a centripetal force, strongest in the urban poles with monumental walled settlements where Islamic codes of conduct and worldviews are dominant, and weakest in the countryside, but it also maintained complex dynamic of interaction in which the countryside supported and interact with the urban centers.14

Hausaization is also reflected in the internal diversity of the Hausa world which was accentuated by its inclusivist nature; integration into Hausa had always been easier compared to the majority of its more exclusivist neighbors. Throughout history, various social classes and groups from other parts of Africa, including rulers, traders, immigrants and enslaved persons, identified themselves as Hausa by acculturating themselves into Hausa culture.15

A recurring dichotomy among Hausa societies is that between ‘Azna’/Maguzawa group (often described as non-Muslim), and the Muslim Hausa (sometimes called ‘dynastic’ Hausa). Azna spiritualism is negotiated by clan-based groups through divination, sacrifice, ritual offerings, possession (bori), and magic, in attempts to influence human affairs and natural processes16. The Azna and Maguzawa also used to be characterized by particular types of facial and abdominal markings called zani, by the preference of living in rural areas rather than in walled towns.17

The ‘Dynastic Hausa’ comprised the bulk of the urban population in the walled towns and the diaspora communities. The Hausa’s adoption of Islam was marked by accommodation and syncretism, and shaped by the agency of individuals, and the religion was fairly influential across all spheres of social and political life in most of the major Hausa centers since at least the 11th-15th century. Its the cosmopolitan, mercantile and urban Hausa who were therefore more engaged in the long distance trade networks from which the diasporic communities emerged.18

Long-distance trade and the creation of a Hausa Diaspora.

The Hausaland underwent a period of economic expansion beginning in the 15th century largely due to the city-state’s participation in long distance trade. A significant textile and leather industry emerged in the cities of Kano, Zaria and Katsina where indigo-dyed cloth, leather bookcases, footwear, quilted armour and horse-equipment were manufactured and sold across west Africa and north Africa. By the 17th century, Kano's signature dyed cloth was the preferred secondary currency of the region, finding market in the states of Bornu and the Tuareg sultanate of Agadez19. However, the majority of this trade involved the travel of itinerant merchants to the Hausalands to purchase the trade items, and rarely involved the Hausa merchants themselves travelling outside to find markets for their products.20

This pattern of exchange shifted with the growth of the Kola-nut trade that saw Hausa merchants venturing into markets outside the Hausalands, and in the process spreading the Hausa language and culture in regions outside the Hausalands creating what is often termed a trading diaspora.

Trade diasporas are described as groups of socially interdependent, but spatially dispersed communities who have asserted their cultural distinctiveness within their host societies in order to maintain trading networks spread across a vast geography.21 The creation of a trade diaspora involved the establishment of networks of merchants that controlled the external trade of Hausa states through their interaction with the dispersed trade centers across the region. These merchants primarily used Hausa as a language of commerce and outwardly adopted aspects of Hausa culture including religion, dress and customs.22 It was in this diaspora that the fluidity of Hausa identity and its easy of social mobility enabled the expansion of the Hausa communities as different groups acculturated themselves to become Hausa, making Hausa-ness a 'bridge' across the ethnic labyrinth of West Africa. The Hausa diaspora in the Volta basin of Ghana for example, also included originally non-Hausa groups who traced their origins to Agadez (Tuareg), Nupe (Yoruba), Bornu (Kanuri), and elsewhere in the Central Sudan, but who came to identify themselves as Hausa.23

The Hausa trading diaspora joined other older established diasporas in the region especially the Dyuula/Juula/Jakhanke (attimes also considered Wangara)24, whose trade was mostly oriented to the regions west of the Niger river (from Timbuktu to Djenne, to the Sene-gambia), to form an interlocking grid of commercial networks, each covering a distinct geographical area and responding to separate market demands, despite extensive overlap. In time, Hausa came to displace Juula as the primary lingua franca in most regions of the Volta basin.25

Kola-nut is a caffeinated stimulant whose plant is native to the west-African forest region especially in the River volta basin (now found in the Ivory coast, Burkina Faso, Ghana, Togo and Benin) and the region was politically dominated by several states including Dagbon, Gonja, Wa, Gyaman, Mamprusi (all of which later came under Asante suzerainty in the 18th century), as well as Borgu and northern Dahomey. The earliest account of Kola-nut trade in the Hausalands comes from the reign of Sarki Abdullahi Burja of Kano (r. 1438-1452) when the trade route to the Gonja kingdom for Kola was first opened.26

19th century manuscript from northern Nigeria identifying the types of Kola and their medicinal and recreational uses. (Ms. Or. 6880, ff 276v-277v British Library27)

But the most significant influx of Hausa merchants begins in the period between the late 17th century and the mid-18th century with the establishment of Kamshegu in Dagbon (northern Ghana) by Muhammad al-Katsinawı28. Hausa merchants arrived in Mamprusi (also in northern Ghana) in the early 18th century where they served as the first four imams of the capital's mosque. In Gonja, they settled at the town of Kafaba (northern Ghana) where a significant Hausa community was in place by the 1780s, In northern Dahomey they settled in the town of Djougou (northern Benin) which grew into a significant commercial capital. 29

While the majority of these Hausa diasporas were established by itinerant merchants, the social classes that comprised the diaspora community were extremely varied and included scholars, mercenaries, craftsmen, and other groups. The term “trading diaspora” should therefore not be taken in the strictest sense to describe the commercial activities of the merchant community alone but in reference to the social complexity of the diaspora community.30

Hausa barber at a market in Bali, Cameroon (c. 1933 Basel Mission Archives)

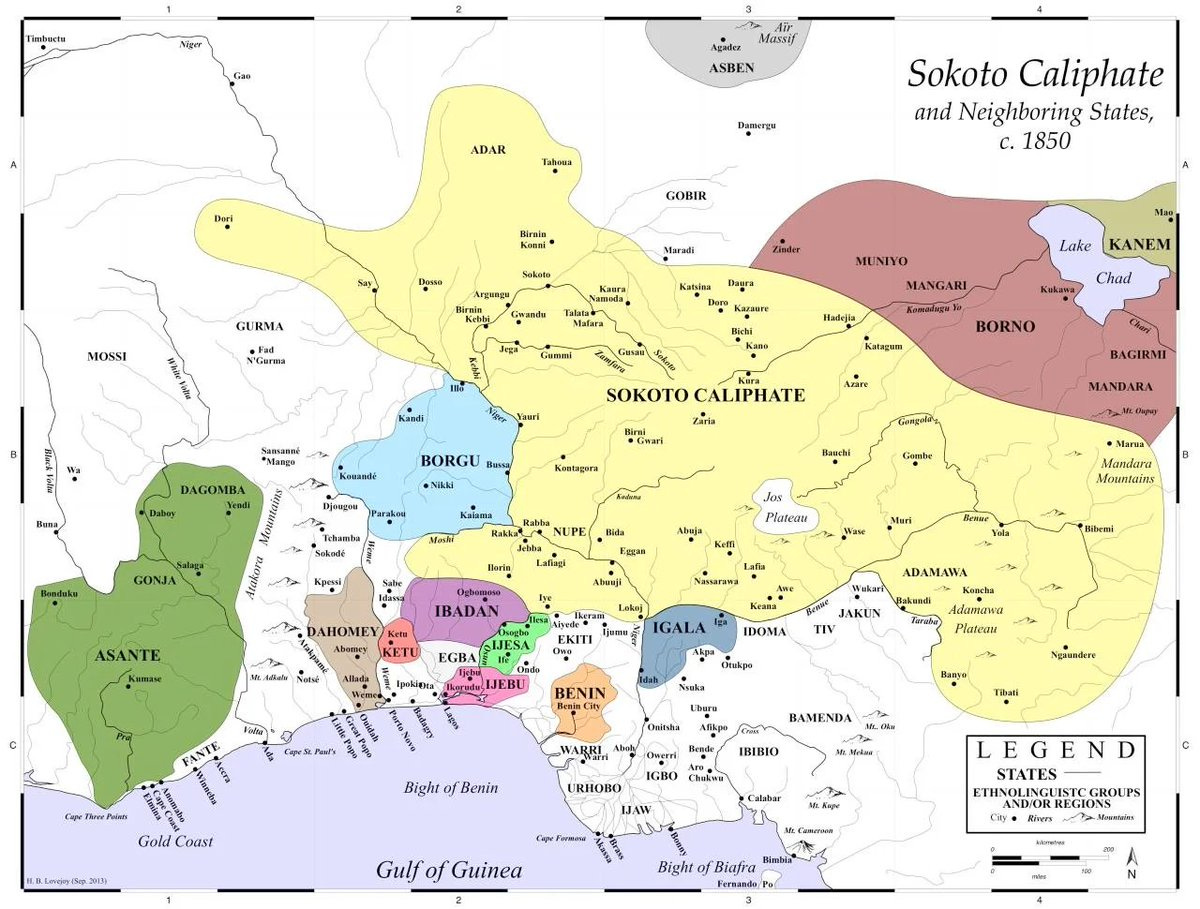

In the early 19th century, the consolidation of the Asante state's northern provinces, and the establishment of the Sokoto caliphate (which subsumed the Hausalands), gave further impetus to the expansion of the Hausa diaspora and entailed major demographic and commercial changes. The effects of the both political movements in Asante and Hausalands were two-fold, first was the expansion of the already-existing Hausa diaspora in the Volta river Basin, and second; was the creation of new Hausa diasporas in the region of what is now north-western Cameroon and later in Sudan.

West-Africa’s political landscape in the mid 19th century showing the two dominant states of Asante and Sokoto (including the latter’s province of Adamawa)

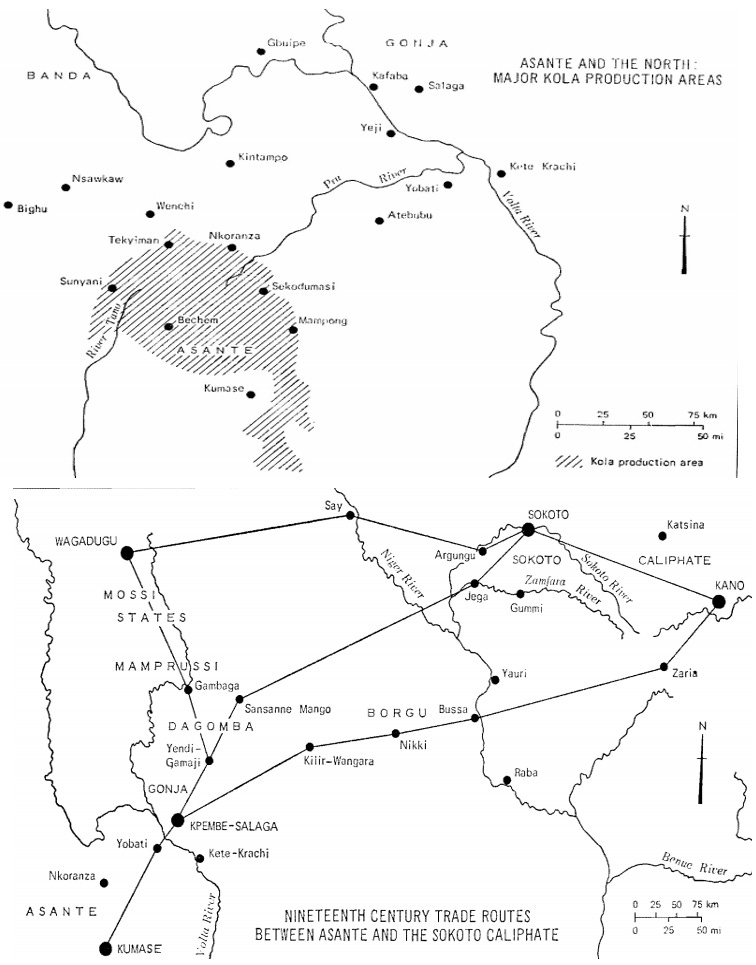

The Asante kingdom centralized the Kola-nut trade through royal agents and northern merchants (that included the Hausa), and developed Salaga into the principal metropolis which connected the Kola-nut producing region then fully under Asante control, with the Hausalands.31 The rapid expansion of the Kola-nut trade between Asante and Sokoto, resulted in the establishment of trade towns across the northern provinces of Asante and the emergence of the Hausa network as the dominant commercial system throughout Borgu and the Volta basin and the adoption of the Hausa language as the lingua franca in all the towns and cities along the trade routes.

the Kola-nut producing regions within Asante and the trading towns and the trade routes between Asante and Sokoto32

several Hausa merchant-scholars are attested in the Volta region, such as Malam Chediya from Katsina, who established himself at Salaga in the early 19th century where he became a prominent landowner.33 By the 1820s, the city of Salaga and Gameji (in north-western Nigeria) were reportedly larger than Kumasi the Asante capital due to the influx of trading diasporas such as the Hausa.34 In the town of Yendi, Hausa scholars such as Khalid al-Kashinawi (b. 1871) from Katsina established schools in the town and composed writings on the region's history among other literary works. 35 another was Malam Ma'azu from the city of Hadejia who established himself at the town of Wenchi in the mid 19th century36, The Hausa diaspora grew cross the central and southern Asante domains in Ghana, these communities were often called ‘zongo’37 and from them, emerged prominent Hausa who were included in the Asante central government (often with the office title ‘Sarkin’ which is derived from Hausa aristocratic titles) and most were employed in making amulets.38 and by the late 19th century, a Hausa diaspora had been established in coastal Ghana including in the forts of Accra and cape-coast, with prominent Hausa merchant-scholars such as Malam Idris Nenu who came from Katsina and established a Hausa community in Accra39

Malam Musa, the Sarkin Zongo of Kumasi, Ghana from 1933-1945, (c. 1936 Af,A15.4 british museum) the ‘Sarkin Zongo’ was one of several offices in Asante but both words are derived from Hausa and were often occupied by Hausa title-holders continuing into the colonial era and independent ghana40

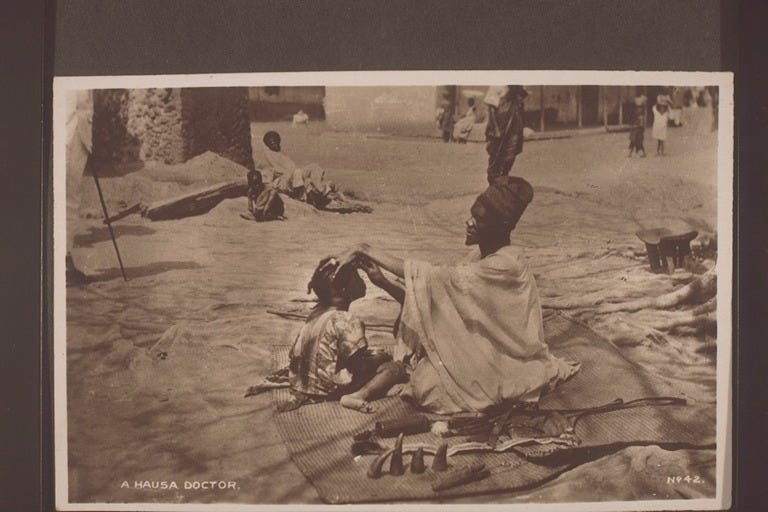

a Hausa doctor in cape-coast, Ghana ( c. 1921 Basel Mission Archives)

In northern Togo, the Hausa settlement at kete-Kratchi was established following the decline of Salaga after the Anglo-Asante war of 1874, and by 1894 Kete had a large market described by the explorer Heinrich Klose "all goods a heart could wish for are offered here, besides the european materials from the coast, the most important are the Hausa cloths coming from inland., often one can see the busy Hausa tailor sewing his goods on the spot. The beautiful and strong blue and white striped african materials are brought by the caravans from far Hausa lands".

Kete was also home to the Hausa scholar Umar al-Kanawi (b. 1856) his extensive writings about Hausa societies, history and poetry did much to establish Hausa, definitively, as a literary language in much of the Greater Voltaic Region. 41

photo from 1902 showing a rural mosque under construction at Kete-Krachi in Ghana (then Kete-Krakye in German Togo), Basel Mission archives

The Hausa Diaspora in Cameroon and Sudan: the Kingdoms of Adamawa and Bamum.

In Cameroon, both trade (in Kola-nut and Ivory) and proselytization encouraged the expansion of Hausa trading diaspora into the region in the decades following the establishment of the Adamawa province by the Sokoto rulers in 1809. Before the 19th century, the region of what is now north-western Cameroon had been ruled by loosely united confederacies of Kwararafa and Mbum, both of which had been in contact with the Hausa since the 15th century,42 and had adopted certain aspects of Hausa culture including architecture and dressing, in a gradual process of acculturation and syncretism which continued after the Sokoto conquest of the region.43

By 1840, Hausa traders had established themselves in south-central and northern Cameroon where there were major kola-nut markets44, and had formed a significant merchant community in Adamawa's capital Yola by the 1850s45 (Yola is now within Nigeria not far from the Cameroon border). By the 1870s, the Hausa quarter in Yola included scholars, architects (such as Buba Jirum), craftsmen, mercenaries and doctors.46 The Hausa connected the regions’ two main caravan trade routes; the one from Yola to Sokoto, with the one from Yola to the Yorubalands (in what is now south-central Nigeria), where the Niger Company factories were located at Lakoja.47 becoming the dominant merchant class along these main routes.

By the late 19th century, Hausa merchants and scholars were established in the Bamum kingdom's capital of Fumban. The first group of itinerant Hausa merchants came to Bamum during the reign of King Nsangu (r. 1865-1885) to whom they sold books, and textiles48. More Hausa groups settled in Fumban and established a fairly large diasporic community, especially after the invitation of the King Njoya following Adamawa's assistance in suppressing a local rebellion in Bamum. Njoya had been impressed with the Adamawa forces' performance in battle and chose to adopt elements of their culture including the adoption of Islam (that was taught to him by a Hausa Malam), and Njoya’s eventual innovation of a unique writing system; the Bamum script, that was partly derived from the Ajami and Arabic scripts used by his Hausa entourage.49

Hausa musician in Fumban, Hausa teacher in Fumban ( c. 1911, 1943, Basel Mission Archives)

Islam had for long provided the dispersed commercial centers with a unity crucial in maintaining the autonomy of individual settlements and in allowing the absorption of other groups.50 By 1900s, there was a significant level of syncretism between the Bamum and Hausa culture particularly in language, dressing and religion, and Hausa merchants handled a significant share of Bamum's external trade; as one Christian mission wrote in 1906 "When we entered Bamum, it was just market [day]. We saw well above two hundred people. The soul of these markets are of course the Hausa. One can simply buy everything in this market, cloth, Hausa garments, shoes, leather, then all kinds of foods, also fresh beef, rancid butter, firewood, and shells which take the place of money, and much more".51

While the Hausa language’s relatively recent introduction in western Cameroon didn’t enable it to became the sole lingua franca of the region, the trade networks augmented by the Hausa merchants eventually made Hausa an important trade language in the region.

a small party of Hausa traders in north-west cameroon with their donkeys. (c. 1925, BMI archives) the long-distance caravans usually had over 1,000 people and an equal number of pack animals, smaller trading parties such as this one were mostly engaged in regional trade.

The Hausa Diaspora in Sudan.

A similar (but relatively recent) Hausa diaspora was established in Sudan beginning in the late 19th century in the towns of el-Fashir and Mai-Wurno, This Hausa diaspora in Sudan was the product of the use of the old Pilgrimage route through Sudan, as well as the Anglo-Sokoto colonial wars of the early 20th century which forced some Hausa to move to Mai-Wurno along with the Sokoto elite. a number of Hausa scholars were employed in the Darfur kingdom of Ali Dinar (r. 1898 -1916 ) shortly before it fell to the British, however, most Hausa arrived in the Sudan when it was already under British occupation. The Hausa Diaspora in Sudan is thus the eastern-most Hausa community from the pre-colonial era.52

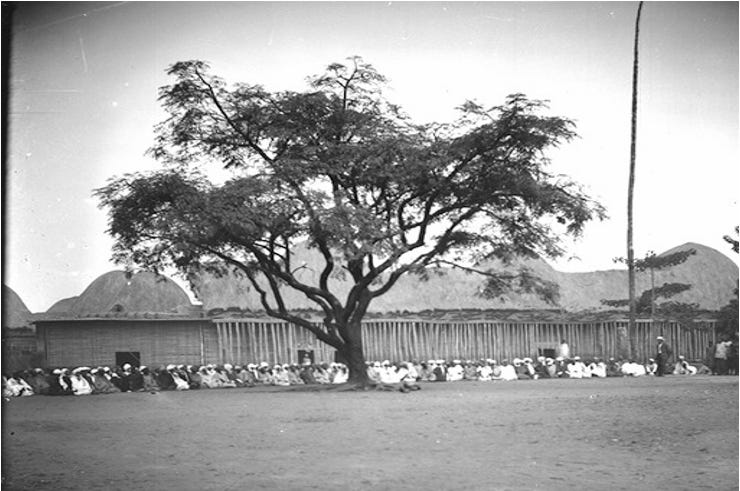

‘Hausa at prayer’ in Bamum, Cameroon (c. 1896 Basel Mission archives)

Conclusion: the role of the Hausa diaspora in creating a west African lingua franca.

The relatively vast geographical extent of the Hausa language is a product of the dynamic nature of the Hausa diasporic communities and culture. Trade diasporas such as the Hausa’s, are a core concept in African history particularly in west Africa where spatial propinquity and ethnic diversity necessitated and facilitated the development of common linguistic and cultural codes. 53

The Hausa diaspora presents an example of a relatively recent but arguably more successful model of a dispersed community in West Africa. The nature of the Hausa states’ political systems which encouraged the acculturation of diverse cultural groups into assuming a Hausa identity, and their participation in long distance trade, encouraged the emergence of robust diasporic communities, and ultimately enabled the rapid spread of Hausa language into becoming one of the most attested languages in Africa.

Subscribe to my Patreon account for more on African history and Free books on the Hausa Diaspora

Huge thanks to ‘HAUSA HACKATHON AFRICA’ which contributed to this research.

Rural Hausa: A Village and a Setting By Polly Hil pg 3

Planta Slavery in the Sokoto Caliphate: A Historical and Comparative Study By Mohammed Bashir Salau pg 33

Being and Becoming Hausa by Anne Haour pg 3

Some considerations relating to the formation of states in Hausaland' by A. Smith

A Historical 'Whodunit' by JO Hunwick

A Geography of Jihad by Stephanie Zehnle pg 179-180)

Towards a Less Orthodox History of Hausaland by J. E. G. Sutton pg 182

Being and Becoming Hausa by Anne Haour pg 47

Being and Becoming Hausa by Anne Haour pg 38-48, 47 )

Being and Becoming Hausa by Anne Haour pg 67-69)

A Reconsideration of Hausa History before the Jihad by Finn Fuglestad pg 338-339, Government In Kano, 1350-1950 by M. G. Smith pg 154

Plantation Slavery in the Sokoto Caliphate: A Historical and Comparative Study By Mohammed Bashir Salau pg 34

Being and Becoming Hausa by Anne Haour pg 18

Towards a Less Orthodox History of Hausaland by J. E. G. Sutton by 184

Being and Becoming Hausa by Anne Haour pg 6)

Histoire Mawri by M. H. Piault pg 46–47)

Islam and clan organization amongst the Hausa by J Greenberg 1947 pg 19565)

Caravans of Kola: The Hausa Kola Trade 1700-1900 by P.E. Lovejoy pg 39-40

The Desert-Side Economy of the Central Sudan by Paul E. Lovejoy and Stephen Baier pg 555-556

Government In Kano, 1350-1950 by M. G. Smith pg 22-24

“Cultural Strategies in the Organization of Trading Diasporas,” by (Abner Cohen,

Caravans of Kola: The Hausa Kola Trade 1700-1900 by P.E. Lovejoy pg 31)

The Formation of a Specialized Group of Hausa Kola Traders in the Nineteenth Century by P. Lovejoy pg 634).

The History of Islam in Africa by Nehemia Levtzion Pg 94

Caravans of Kola: The Hausa Kola Trade 1700-1900 by P.E. Lovejoy pg 33-34)

Government In Kano, 1350-1950 by MG. Smith pg 124)

Arabic Literature of Africa, Volume 4 by J. Hunwick pg 541

Caravans of Kola: The Hausa Kola Trade 1700-1900 by P.E. Lovejoy pg 36)

The Hausa Factor in West African History by Mahdi Adamu pg 15-17

Caravans of Kola: The Hausa Kola Trade 1700-1900 by P.E. Lovejoy pg 18-19)

Caravans of Kola pg 16

Caravans of Kola: The Hausa Kola Trade 1700-1900 by P.E. Lovejoy pg 38)

Caravans of Kola: The Hausa Kola Trade 1700-1900 by P.E. Lovejoy pg 39)

Arabic Literature of Africa, Volume 4 by J. Hunwick pg 59

Asante in the Nineteenth Century by I Wilks pg 297

People of the zongo by Enid Schildkrout

Asante in the Nineteenth Century By Ivor Wilks pg 230-270

Landlords and Lodgers: Socio-Spatial Organization in an Accra Community By Deborah Pellow pg 47-48

Islam and identity in the Kumase Zongo by Kramer, R.S, pgs 287-296, in “The cloth of many colored silks: Papers on history and society, Ghanaian and Islamic in honor of Ivor Wilks”

Nineteenth Century Hausaland: Being a Description by Imam Imoru of the Land, Economy and Society of His People by Douglas Edwin Ferguson pg 20-23)

Beyond the World of Commerce: Rethinking Hausa Diaspora History through Marriage, Distance, and Legal Testimony by H O'Rourke pg 148)

Conquest and Construction by Mark DeLancey pg 19-21)

African Crossroads: Intersections Between History and Anthropology in Cameroon by Ian Fowler, David Zeitlyn pg 135)

Fulani hegemony in Yola (Old Adamawa) 1809-1902 by M. Z. Njeuma pg 120-121)

Fulani hegemony in Yola (Old Adamawa) 1809-1902 by M. Z. Njeuma pg 60)

Fulani hegemony in Yola (Old Adamawa) 1809-1902 by M. Z. Njeuma pg 139)

The Assumption of Tradition: Creating, Collecting, and Conserving Cultural Artifacts in the Cameroon Grassfields (West Africa) by Alice Euretta Horner pg 176)

African Crossroads: Intersections Between History and Anthropology in Cameroon by Ian Fowler, David Zeitlyn pg 144)

Caravans of Kola: The Hausa Kola Trade 1700-1900 by P.E. Lovejoy pg 39)

African Crossroads: Intersections Between History and Anthropology in Cameroon by Ian Fowler, David Zeitlyn pg 170)

Hausa in the Sudan: Process of Adaptation to Arabic by Al-Amin Abu-Manga

see chapter: ‘Strangers, Traders’ in “Outsiders and Strangers: An Archaeology of Liminality in West Africa” By Anne Haour

I am particularly happy with this project because I believed that it's through the study of our language, culture and history we can develop and contribute to human civilization.