The Dahlak islands and the African dynasty of Yemen

a complete history of a cosmopolitan archipelago in the red sea (4th-19th century)

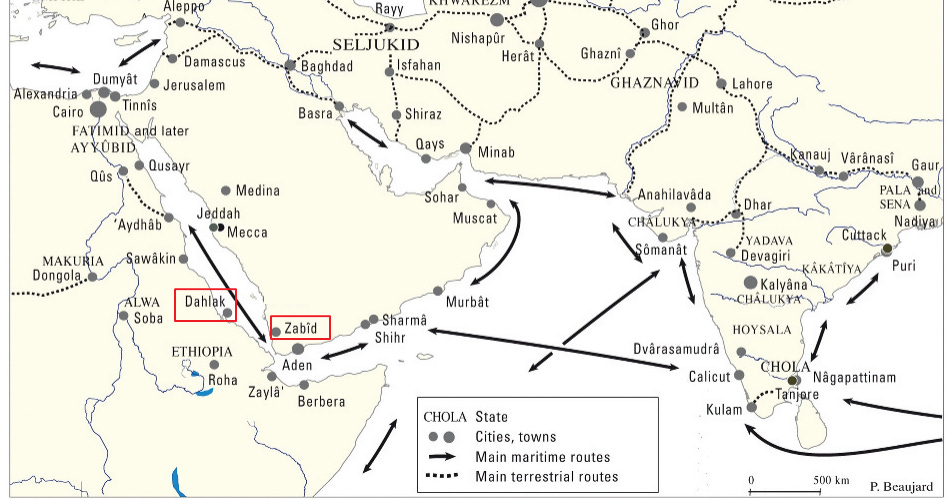

At the height of the middle ages, a small group of islands in the red sea near the Eritrean coast featured prominently in the navigational instructions of merchant ships plying the ocean routes connecting Fatimid Egypt to the Indian ocean world.

Now known for pearl fishing and scuba diving, the Dahlak archipelago was once home to a cosmopolitan community hailing from the African mainland and places as far as the Caspian sea. The islands were the seat of a local kingdom that played a significant role in the regional politics of Ethiopia, Egypt and the Arabian peninsula, and it served as the base for the emergence of an African Mamluk dynasty which ruled southwestern Yemen for over a century.

This article outlines the history of the Dahlak islands, and the Najahid dynasty of Yemen.

Map showing the location of Dahlak in the red sea and indian ocean world1

Support AfricanHistoryExtra by becoming a member of our Patreon community, subscribe here to read more about African history, download free books, and keep this newsletter free for all:

Early history of the Dahlak islands from the Aksumites to the Ziyadids of Yemen (4th-10th century)

The Dahlak archipelago is a group of hundreds of islands off the coast of Eritrea, the largest of which is Dahlak al-Kabīr. The islands were contested territory that was under the control of various powers based on the African and Arabian mainland, before the emergence of an independent kingdom in the 11th century.

The earliest settlement on Dahlak was founded during the Aksumite era, as evidenced by the ruins of a 'Christian church' from the 4th century and the discovery of several Aksumite coins.2The archipelago was most likely predominantly settled by groups from the African mainland but also received substantial numbers of settlers from the Arabian peninsula

After the 7th century wars between Aksum and the early caliphates (Rashidun and Umayyad), the Dahlak archipelago had a Muslim population, and some of the islands became ideal places for exiling rebellious figures in the Umayyad administration beginning in 702, and continuing in 715 and 743-744. This practice continued under the Abbasid empire in the 750 and 760s before the archipelago reverted to the control of the declining Aksumite state in the 9th century, according to al-Yaʿqūbī, who refers to its as “the island of the nejashi".3

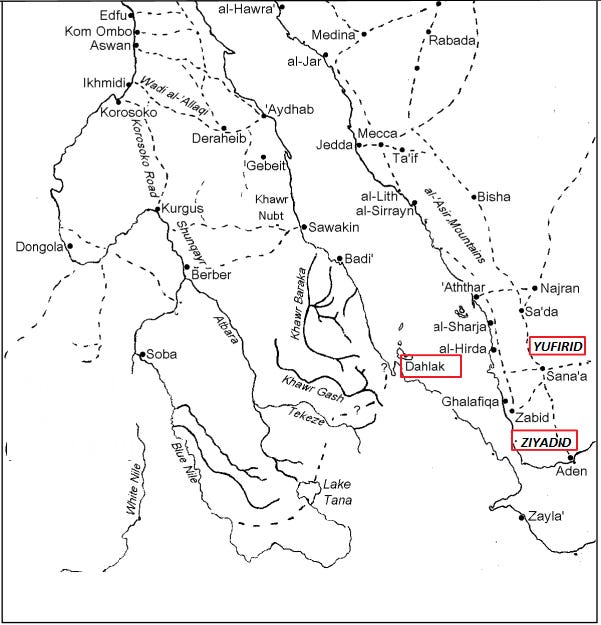

By the turn of the 10th century during the disintegration of the rump Aksumite state, the archipelago came under the political orbit of the Ziyādid dynasty of Zabīd in south-western Yemen to which it paid tribute consisting of amber, panther skins and captives from various sources on the mainland. The exact nature of the Ziyadid's authority over Dahlak is unclear, it's likely that the island settlers simply maintained a policy of deference to their more powerful neighbor, as most contemporary writers only mention of special treaties between the Ziyadid rulers and Dahlak’s settlers rather than direct control.4

The period of Ziyādid influence over Dahlak and the southern red sea region was relatively short and was likely connected to the Sudanese gold trade in which Dahlak also features as one of the places where gold dust from the Shunqayr mines could be bought according to Yemeni geographer al-Hamdānī (d. 945). 5 The archipelago retained its status as a cosmopolitan hub under Aksumite and Ziyadid influence. For the period between 864 and 1010, the necropolis of Dahlak contains 89 stelae that refer to diverse groups of people claiming exogenous origins from Arabia, to Iran to Byzantium.6

engraved tombstones from the necropolis of Dahlak7

The ‘sultanate’ of Dahlak and the Mamluks of Yemen in the 11th century

The first local king (sultan) of Dahlak appears in the 11th century, coinciding with the establishment of the dynasty known as the Najāḥids. The Najāḥids were a dynasty whose founder was Najah; a military slave of "Abyssinian" origin. The term Abyssinian/Habsha as used in the Arabian peninsula during the middle ages was a catchall term for people from the northern Horn of Africa region, not necessary confined to the boundaries of modern Ethiopia .

Enslaved soldiers were central figures in the armies of Islamic world from the 9th century; a phenomenon that was rather unexceptional in world history, being inherited from the social institutions of the preceding empires. These soldiers, who were initially favored for their neutrality in internal factionist politics, eventually gained tremendous influence and power through their military and political service.8

Military slaves of African origin were relatively rare in the Islamic empires outside Africa —the bulk of the captives in the Muslim empires of western and central Asia were often taken from a diverse range of sources extending from eastern Europe to central Asia and northern India, depending on the location of the state and the trade routes9. Some of the military slaves that would eventually become prominent in Islamic politics of the middle ages were derived from the campaigns of the Mongol empire across central Asia and eastern Europe. The Mongol campaigns invigorated the slave routes which preceded them, and fed large numbers of captives to meet both domestic demand and demand from its southern neighbors in Delhi and Egypt, where contemporaneous slave dynasties (Mamluks) were later established in the 13th century when the slaves had gained significant political power.10

In Yemen, enslaved soldiers also came from diverse origins despite the region's proximity to the African mainland. Military slaves are attested in the region since the late 1st millennium, continuing until the early modern period. "Abyssinian" soldiers initially constituted the bulk of these military slaves during the Ziyadid era (818-1018), but were largely replaced by Turkish and Circassian slaves by the time of the Ayyubid (1171–1260), Rasulid (1229–1454) and Tahirid (1454–1517) dynasties. While these Turkish and Circassian slave soldiers remained a formidable political group in Yemen's politics especially in 1250, 1322, 1442 and 1451 when they played king-maker, they never managed to seize authority like their peers had in Egypt and Delhi. It was only the Abyssinians who managed to establish an independent Mamluk dynasty in Yemen.11

Prior to the ascendance of Najahids in 1021, the south-western coast of Yemen and Saudi Arabia (Tihama) was dominated by two competing kingdoms since the 9th century; the Yufirids in the city of Sana'a, and the Ziyadids in the city of Zabid. After the death of sultan Ishaq the last powerful Ziyadid ruler in 981, Zabid was attacked by the Yufirids in 989, but the kingdom was saved by the intervention of al-Husayn bin Salamah. The latter was an Abyssinian official who served as vizier (governor) during the interregnum and raised the young prince of the deceased sultan. Al-Husayn was then succeeded as vizier by another Abyssinian official named Mardjan, who entrusted the regency to his Abyssinian administers Nafis and Najah, but the former conspired with Mardjan to kill the boy-king and assume the title of sultan. In 1021, Najah entered Zabid and executed both Nafis and Mardjan, and assumed the office of sultan.12

The southern red sea region during the 10th century13

The Najahid dynasty of Yemen from 1021-1159

However, this early history about the fall of the Ziyādid and the rise of Najah as narrated by Jayyash (Najah's son) to a local Yemeni historian named Umara is partly contradicted by the discovery of coinage mentioning atleast two of Ishaq’s successors named Ali b Ibrahim, and his sons; al-Muzaffar Alï and Alï al-Muzaffar between Ishaq’s death, re-dated to 974, and the first appearance of Najah’s coins around 1032 that also bore the last Ziyadid sultan’s name. While the role of the Abyssinian officers was likely true -since similarly high-ranking officials continue to wield significant influence during the Najahid era, the story about the regency was likely embellished by Jayyash for legitimacy. Najah did receive the recognition of the Abbasid caliph who granted him the titles al-Mu'yyadd Nasr al-din, and he ruled as nearly independent sovereign of the former Zayidid realm extending from Tihama to Zabid. This honorific title is also attested on the coins struck jointly by Najah and the last Ziyadid ruler Alï al-Muzaffar, who likely had little formal authority at the time.14

While Najah controlled the coastal regions of south-western Yemen, his power on the mainland was contested by the rise of the Sulayhids whose founder Ali al-Sulayhi took over Sana'a from the Yufirids and challenged Najah's authority in a conflict that culminated with Najah's assassination by poisoning in 1060. Ali then occupied Zabid and forced Najah's two sons Sa'id and Jayyash to flee to Dahlak which they turned into their capital.15 Sa'id and Jayyash then plotted to avenge their fathers' death, and in 1081, they returned to Zabid and executed Ali. Sai'd was installed using the support of the military, which primarily consisted of Abyssinian soldiers. While Sa'id was briefly forced out in 1083 by Ali's son al-Mukarram, he returned in 1086 and established the city of Hays which he populated with Abyssinian soldiers. But in 1088, al-Mukrram returned with a large force that invaded Zabid and killed Sa'id, forcing his brother Jayyash to flee to exile in India.16

Jayyash returned to Zabid in 1089 disguised as an Indian merchant, accompanied by his son Fatik born to an Indian woman. Jayyash plotted with the Abyssinian soldiers left by his brother and regained power in 1089, ruling peaceful until his death in 1105. He was succeeded by his son Fatik who had a relatively short reign marked by a succession conflict with his brothers that continued after his death in 1109. Fatik was succeeded by his son al-Mansur who fled the conflict between his uncles and sought support from the Sulayhids. He was eventually installed as a client of the Sulayhids in 1111 but was challenged by his vizier who he replaced in 1123 by another named Mann Allah, but was killed by the same in 1130. al-Mansur's wife had Mann Allah executed, and using her own viziers, installed her son with al-Mansur named Fatik II who reigned until 1137. Fatik II was deposed during conflicts between the various viziers and was replaced by his cousin Fatik III who had a relatively long reign though effective power remained with the viziers. By 1159, a new and short-lived Mahdid dynasty which had replaced the Sulayhids in Sana'a, advanced into Zabid and executed Fatik III, assuming power for a few years before the Ayyubids of Egypt conquered Yemen.17

Old city of Zabid, Yemen

The Dahlak archipelago during the Najahid era

Like the rest of South-western Yemen, the Dahlak archipelago reached its height as an international trading hub under the Najaḥid period (1022-1159). The market of Dahlak was an important stop-over point for the long distance maritime trade between Fatimid Egypt and the western Indian ocean. This trade was often segmented with individual ships following fixed routes between ports, as evidenced by the route taken by Joseph Lebdi between Cairo and India in 1097–98 which didn't call at the port Aden but chose the port Dahlak instead.18

Besides the transshipment trade from which it drew the bulk of its wealth by taxing merchant ships, Dahlak also provided commercial services including clearing customs, as well as serving as a base of rescue and salvage operations. The island authorities minted their own gold coins and used them in international trade especially with the Fatimids of Egypt. The rulers of Dahlak were themselves merchants and according to Geniza documents, they exported a marine product named drky which, along with pearls constituted a lucrative trade.19

The political relationship between Dahlak and the Najahids was unclear but its likely to have been more direct than their predecessors, with the exiled Najahids reportedly 'practicing treachery against the Prince of Dahlak'.20

Many of the ruins found on the islands date back to this period. They include large houses built of carved coral blocks, two mosques, funerary monuments, and an extensive water supply system comprising numerous cisterns. There are also more than 62 stelae recovered from this period, belonging to a diverse group of travelers, religious figures and merchants, claiming origins from various regions. Despite the appearance that Dahlak's population was transient, it's likely that the bulk of the settlers were of local origins, since the epithets used on the tombstones only claimed distant connections to a place that didn't necessarily reflect the persons' immediate provenance.21

Dahlak also maintained some contacts with the African hinterland, with a few of its families also settled at Bilet (Kwiha in Tigray, Ethiopia) where more than 40 funerary stelae have been recovered including some exceptional ones belonging to individuals from southern Egypt's Wādī ʿAllaqī mining region.22

The mosque and necropolis of Dhalak23

Carved basalt tombstones of Abi Harami al-Makki (d. 1188) and Salim al-Sawakini (d. 1210) at the British museum (No. 1928,0305.1, 1928,0305.2) while the nisba of al-Makki gives this person a likely origin in mecca, the nisba of al-Sawakini is evidently of eastern-Sudanese origin associated with the Beja and Hadariba inhabitants of Suakin

The Dahlak islands from the 13th-19th century

The commercial prosperity of Dahlak declined beginning in the 12th century, as the archipelago was transformed from a trans-oceanic hub connecting the red sea and western Indian ocean, into a regional hub whose activities were confined to the southern red sea region. In the 13th century, Ibn Said mentions that the king of Dahlak was an Abyssinian Muslim who maintained his independence from the ruler of Yemen24. Stele found on the archipelago dating from the 12th century to 13th century mention the presence of merchants who styled themselves as 'sultans' in an imitation of the Najaḥids but had little political authority. Most claim exogenous origins except one 'Ethiopian' named Rizqallāh al-Ḥabašī (d. 1214). And according to Abū al-Fidāʾ (d. 1331), the island was ruled by a local "Abyssinian" Muslim who maintained contacts with the Mamluk dynasty of Egypt and the Rasūlid dynasty of Yemen.25

The political landscape of the northern horn of Africa was transformed by the emergence of the Solomonic state in the late 13th century, which expanded to the red sea region by the early 14th century and sacked the Dahlak archipelago several times during its wars with various Muslim polities in the region. But these wars may not have contributed significantly to its decline because in 1393, the ruler of Dahlak sent a gift of several elephants to the Mamluk sultan of Egypt according to al-Maqrizi.26

The archipelago had sank further into decline by the early 16th century and it was under the rule of a local sultan named Aḥmad b. Ismāʿīl when the Portuguese arrived and briefly occupied it during hegemonic wars with the Ottoman empire. Aḥmad b. Ismāʿīl later joined the Adal-Ottoman alliance that invaded the Solomonic state in 1526 and received the coastal province of Ḥǝrgigo as reward. By 1541, the Dahlak archipelago was under the control of the ruler of Massawa on the coast of Eritrea.27

In 1557, Dahlak and the mainland port of Massawa were occupied by the Ottoman empire. The region became a neglected province of secondary status to the Ottomans, who nevertheless constructed some more stone houses. Dahlak Kebir gradually declined in importance under the late Ottoman era, being described as a modest collection of villages in the 18th century.28 This situation that prevailed throughout the 19th century, when the islands were home to a vibrant economy based on pearl-diving, just prior to its colonization by the Italians.29

Centuries before the African dynasty of Yemen, an Aksumite general named Abraha controlled a vast kingdom across most of the Arabian peninsular, ruling over a diverse Christian and Jewish population a century before the emergence of Islam.

read about it here;

Map by Philippe Beaujard

Dahlak Kebir, Eritrea:FromAksumite to Ottoman. by Timothy Insol pg 45-46)

The Cambridge History of Africa, Vol. 3 pg 118)

The Cambridge History of Africa, Vol. 3 pg 119)

The Red Sea during the 'Long' Late Antiquity by T. Power pg 255)

A Companion to Medieval Ethiopia and Eritrea by Samantha Kelly pg 90)

photo by @GhideonMusa on twitter

The Cambridge World History of Slavery: Volume 2 pg 343, Slave Soldiers and Islam by Daniel Pipes pg 45-51

for a broad outline on military slavery in the medieval islamic world see; chapter 4-5, and 14-16 in The Cambridge World History of Slavery: Volume 2

The Cambridge World History of Slavery: Volume 2 pg 88-91)

The History and Monuments of the Tahirid Dynasty of the Yemen by by VA Porter pg 25-26, 40)

A history of the Ziyadids through their coinage by A Peli 253, 257-258

Map by Timothy Power

A history of the Ziyadids through their coinage by A Peli pg 254-256

Encyclopedia of Islam, volume 7 pg 861)

Encyclopedia of Islam, volume 7 pg 861, The History and Monuments of the Tahirid Dynasty of the Yemen by by VA Porter pg 39)

Encyclopedia of Islam, volume 7 pg 861)

The Red Sea during the 'Long' Late Antiquity by T. Power pg 277)

Aden and the Indian Ocean Trade by Roxani Eleni Margariti pg 166-167, Thieves or sultans, Dahlak and the rulers and merchants by Roxani Eleni Margariti pg 159)

The Cambridge History of Africa, Vol. 3 pg 120)

Thieves or sultans, Dahlak and the rulers and merchants by Roxani Eleni Margariti pg 157-158)

A Companion to Medieval Ethiopia and Eritrea by Samantha Kelly pg 92)

photo by @GhideonMusa

Islam in Ethiopia. By J. Spencer Trimingham pg 61

A Companion to Medieval Ethiopia and Eritrea by Samantha Kelly pg 92,

The Archaeology of Islam in Sub-Saharan Africa By Timothy Insoll pg 51

A Companion to Medieval Ethiopia and Eritrea by Samantha Kelly pg 93)

Dahlak Kebir, Eritrea:FromAksumite to Ottoman. by Timothy Insol pg 41)

Red Sea Citizens by Jonathan Miran pg

Thanks for yet another great write-up of a fascinating region.