The desert kingdom of Africa: A complete history of Wadai (1611-1912)

On the Myths and Misconceptions of Trans-Saharan trade.

Tucked along the southern edge of the central Sahara was one of Africa's most dynamic states. The kingdom of Wadai established a centralized political order across a diverse geographic and ecological space straddling the arid Sahara and the rich agricultural lands of the lake chad basin, creating one of the largest states in African history that at its height covered nearly 1/3rd of modern Chad.

The emergence of the Wadai kingdom in eastern Chad was part of the dramatic political renaissance that swept across the region following the collapse of the kingdoms of Christian Nubia at the close of the middle ages, and created the cultural characteristics of the societies which now dominate the region. The kingdom’s history features prominently in debates about the role of Trans-Saharan trade in state formation and the economies of pre-colonial west-African societies.

This article outlines the history of Wadai from the kingdom's establishment in the early 17th century to its fall in 1912 as west Africa's last independent kingdom, exploring the role of Trans-Saharan trade in Wadai’s society.

Map showing the kingdom of Wadai in the 19th century

Support African History Extra by becoming a member of our Patreon community, subscribe here to read more about African history, download free books, and keep this newsletter free for all:

Early history of Wadai:

The period preceding the establishment of Wadai was characterized by the upheaval following the collapse of the medieval kingdoms of Nubia in the 15th century, the gradual adoption of Islam, and the establishment of the enigmatic kingdom of Tunjur in the 16th century by islamized Nubian kings in the region between eastern chad and western Sudan with its capital at Uri and later at Ain Farrah.1

Wadai’s traditions retain memories of Tunjur's legacy which they often cast in unfavorable light (to legitimize Wadai's deposition of its dynasty), but nevertheless contend that the kingdom's founder Abd al-Karim was associated with the Jawama’a sect of teachers from the Tunjur era who were analogous to west Africa's malams/marabouts.2 Following the breakup of the Tunjur state and deposition of its ruling dynasty by local elites in Wadai (as well as Dar Fur), the latter begun to create their own imperial and commercial networks that took over much of the Tunjur polity and adopted many of its institutions.3

Wadai's first king Abd al-Karim is the subject of numerous traditions that link him to both the eastern and western societies of the “central Sudan” (roughly the region between Timbuktu and the Nile), with some linking him to the Ja’aliyyin community of the Funj kingdom’s Dongola region, others to the town of Bidderi (an important learning center in Bagirmi kingdom), and others identify him as a student (or companion) of the prominent scholar al-Jarmiyu (d. 1591) from the Bornu empire. Abd al-Karim is then claimed to have overthrown the last Tunjur king Dawud and established Darfur as an independent kingdom in the years between 1611-1635 at his capital Wara.4

ruins of the 16th century Tunjur capital Ain Fara in DarFur region, Sudan

Map showing the Tunjur kingdom relative to the kingdoms of Wadai and DarFur

Wadai government and society

The Wadai administration that developed over the 17th-19th century was largely dominated by the Maba ethnic group, who are speakers Nilo-Saharan language of eastern chad and from whom Abd al-Karim hailed, but the kingdom was a multiethnic affair comprised of dozens of other ethnicities, many of whom migrated into the kingdoms' center, some of whom were part of smaller states that had been subsumed by Wadai, while others were former prisoners of war that were assimilated into the Wadai social structure and settled in provinces as subjects5. At its height in the 18th century, the kingdom's territory constituted nearly 1/3rd of modern chad including the modern north-eastern chad’s Borkou-Ennedi-Tibesti region, as well as the old states of Kanem and Bagirmi in south-western chad, which were under its political influence.6

The kingdom was subdivided into provinces headed by governors of various ranks (Kemakil, and aguids/aqids) who collected tribute/taxes and raised armies7 from the various sedentary agricultural groups at the core (eg the Maba, Kodoi, etc), as well as the nomadic Arab groups in its peripheries (although the Arabs occupied a rather degraded position relative to the rest of the subjects)8. The king was assisted by a council of advisors (Djarma/Jerma) that were responsible for major decisions such as justice (a judge was Faqih), administration of vassals, declaration of war, foreign policy, and an imam to head the religious administration and the scholarly community (Ulema). Below the councilors were the second ranking dignitaries such as the Adjawid (knights), the market administrators, head of craftsmen (sultan el-haddadin) and other officials who implemented the decisions of the court.9

At the center of the capital Wara is a large palace complex enclosed within a 24-acre fortress. The ruins comprise an audience chamber, the sultan’s palace, the palaces of the king’s wives, the main mosque, the so-called house of the marabout, all of which are relatively well preserved within a 4m high, 3m thick defensive wall. Next to these are several building annexes for guards and the king’s courtiers, and a large royal cemetery, that are less well preserved. Most of the constructions were completed by Abd al-Karim’s successor king Kharūt, except the mosque and its originally 12-meter high minaret, that was built in late 18th century.10

Wadai was from its early establishment a major center of learning in the central Sudan and was part of the intellectual network linking scholars from Bornu and Bagirmi with those from Ottoman-Egypt11. In the 1830s, the Tunisian traveler al- Tūnisī, noted that the most lucrative imports to Waddaï and DarFur were gold coins, writing paper, and books of jurisprudence, adding that he knew of no country where Islam was as thoroughly adhered to as in Waddaï12. The German traveler Gustav Nachtigal, in his 1874 account of his visit to Wadai, also claimed that there was a primary school in every village, and 30 schools of higher learning, and that ‘compulsory school attendance’ was on a par with that of his country (Prussia).13

Ruins of the walled complex at the 17th century capital of Wara/Ouara in Chad

19th century Manuscript from a private collection in Abéché, chad (Endangered Archives Programme)

Political history of Wadai from 1655 to 1898

Abd al-Karim was succeeded by his son, king Kharūt (r. 1655-1681) who presided over a relatively prosperous period and is credited in some accounts with the founding of the capital Wara, while other accounts state that he only expanded it. He was succeed by his son Kharif (r1678-1681) who ruled briefly and was killed in a war with a neighboring south-eastern chiefdom of Dar Tama after a long campaign led his soldiers to mutiny, and he was thus succeeded by Ya'qub 'Arūs (r. 1681-1707) who is credited with ending Wadai’s suzerainty to the eastern neighboring kingdom of Darfur.14

Much of the history of Wadai during the 17th century and early 18th century was dominated the relationship with its nominal suzerain the Darfur kingdom whose authority it repeatedly challenged. Wadai had continued to pay tribute to kings of Dar fur during the reign of Darfur king Sulayman, but repeated invasions on the frontier by his successor Ahmad Bukr prompted an invasion of the latter by the Wadai king Ya'qub, whose rapid advance into the center of Darfur was only stopped by Bukr's alliance with Wadai’s southern neighbor, the Bagirmi kingdom as well as the timely procurement of ottoman-Egyptian firearms.15

Wadai continued its expansion under powerful rulers including king Kharüt alşaghir (r. 1707-1747), and his successor Muhammad Djawda Kharif al-Timām (r. 1747-95) who extended Wadai's influenced into the Kanem region, that was taken from the declining empire of Bornu, and the Wadai kings also installed a ruler on the throne of the south-western kingdom of Fitri, which was brought under Wadai's political sphere as a tributary state.16 Darfur invaded Wadai again in retaliation for supporting a rebel prince, but the long war ended with the capture of the Darfur sultan Umar Lel who was confined to the Wadai capital where he later died.17

Djawda is credited with a number of conquests to the south and a period of relative stability in Wadai, when the Darfur king Abu'l-Qasim invaded Wadai in pretext to bury his predecessor, the latter was defeated by Djawda's army and internally deposed in favor of Tayrab, who made a formal peace treaty with Wadai, and created a formal border (tirja) between Wadai and Darfur marked by stone cairns, large iron spikes and walls that ensured peace between the two states for nearly a century. Djawda was succeeded by Şallı Darrit (r 1795-1803) who was relatively weak and his death left as brief succession struggle in Wadai that was won by his son Muhammad Sābūn ibn Saleh.18

Wadai was at its height under king Sābūn (r. 1803-1813), he defeated the Bagirmi army and establish influence over the kingdom by installing an allied ruler and imposing tribute19, the frontier state of dār Tama (in the south-east) was brought firmly into Wadai's political sphere, the former following a war that was in retaliation to Tama's raid's into Wadai that had been supported by Dar Fur's king Muhammad al-Fadl.20

Internal conflicts plagued the reign of Sabun's successors, beginning with the short reign of Busata (r. 1813), who was then succeeded by Yûsuf (1813-1829), whose campaigns ended in his defeat and brief evacuation of Wara, and his reign was considered tyrannical such that members of the state council assassinated him and installed his son Rāqib (r. 1829) who reigned for only a year but died, and was succeeded by Abd al-Aziz (r. 1829/30-1834) who spent much of his brief reign crushing rebellions including retaking Wara from the rebellious councilors.21

Upon Aziz's death in 1834, his infant son Adam was installed, but the Dafur sultan al-Fadl took advantage of the succession struggles to mount an ambitious expedition in 1835 to install the exiled brother of Sabun; Muhammad al-Sharif to the throne in exchange for recognition of Darfur's suzerainty over wadai. Upon his installation, al-Sharif immediately turned against his patron, repudiating the agreement he had made to pay tribute to Darfur, he launched his own campaigns including against Bornu, and shifted his capital from Wara to Abeche in 1850, which later became an important trading city with a population of around 28,000 by 1900. Sharif was succeeded by Ali (r. 1858-1874) and Yusuf (r. 1874-1898), both of whose reigns were relatively stable and who undertook a modest transformation of Wadai to consolidate its status as a regional power in response to the declining power of Bornu, the fall of Darfur in 1874, and its growing foreign contacts with the Sanussiya brotherhood in Libya, as well as the French who had arrived in the region in 1897.22

Abéché in the 1920s

Regional and External trade in Wadai’s history, and the kingdom’s relations with North-Africa’s Sanussiya.

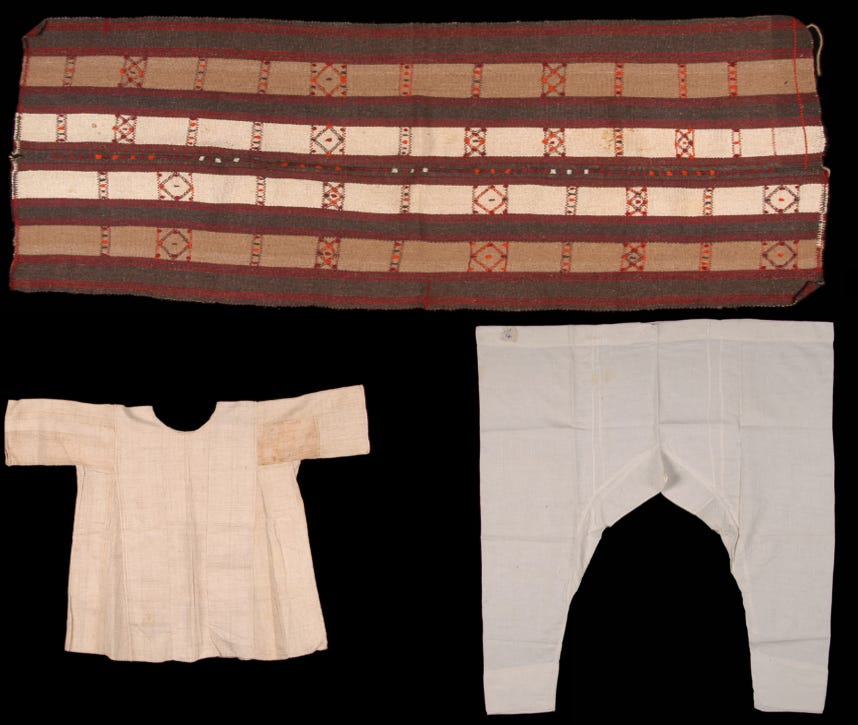

The kingdom's regional and domestic trade was largely based on the region's characteristic farmer-herder exchanges based on ecological variations; with the agricultural products of the Sahel trade for the pastoral products of the Sahara, and supplemented by local specializations in the produce of cloth, leather, iron and copper.23 During the mid-19th century, the Kano market of the Hausalands, was partly supplied by copper from mines south of Darfur, carried west by traders from Wadai.24 Wadai had a significant crafts industry comprised of local metal-smiths and tailors, as well as Hausa leatherworkers25 and Bagirmi craftsmen, its for this reason that most of Wadai's textiles; their accompanying ivory and copper ornaments; leather footwear and horse equipment; weaponry and other implements were made locally, although some was imported west from the Hausalands and Bornu, and north from Tripoli and Egypt.26

Various textiles made in Wadai, early 20th century, Quai branly

Internal trade in Wadai was confined to the main markets held in the capital Abeche and about half a dozen commercial towns across the kingdom, the items sold were mostly agro-pastoral products, as well as locally made textiles and crafts, some regional imports and even fewer Mediterranean imports (less than its neighbors Darfur and Bornu).27 The bulk of Wadai's agro-pastoral trade between the Sahel and Sahara ecological zones that formed the kingdom's main economy, can be gleaned from the various taxes obtained from different provinces which collectively made up the bulk of the state's revenue. With cotton cloths, and riverine produce coming from the south-western provinces, 100-200 loads of ivory and various pastoral products from the southern Arab groups; with horses, camels and grain from the Maba and other groups in the central region of the kingdom; with thousands of head of cattle from the northern Arab groups (cattle, horses and camels appear to have been the most valuable tribute across the region besides grain and formed the bulk of Wadai's external trade to/through DarFur before the 1860s28); with 100 slaves from various southern vassal states including Bagirmi29; and other items including salt, weapons, leather-skins, etc.30

Dyed-leather footwear from Abéché, inventoried in the early 20th century at Quai Branly

Wadai's limited external trade to the Mediterranean markets had for long been directed through DarFur's capital el-Fasher, as Wadai's own northern routes were constrained by its inability to extend firm authority northwards, this challenge which was briefly overcame when a northern merchant stumbled upon Sabun's capital at Wara in 1810, and enabled Sabun to establish a trade route that terminated at the Ottoman-Libyan port city of Benghazi, with trade continuing for about a decade. But this trade later collapsed for extend periods between 1820-1835 as a result of the internal conflicts in Wadai as well as external conflicts with the Ottoman-Fezzan governor of central Libya whose merchants were competing with Wadai, forcing the latter to imprison and/or execute leaders of northern caravans in Wara, confiscate their goods and ban any travelers from the north.31

It was only after the establishment of the Sanūssiyya politico-religious order during the mid-19th century in the region of eastern Libya, and their setting up of well-regulated trade system of trade that the constraints of the Wadai's trade with the northern markets through Beghanzi were removed. The Sanussiya invited many of the nomadic groups north of Wadai into their order; including all kings of Wadai beginning with al-Sharif in 1835, and gradually increased security in the region by mediating merchant disputes.32

The Wadai king Sabun is said to have met with the Sanussiya founder Mohammed ibn al-Sanuss while on pilgrimage to mecca in 1835. From 1836, northern trade was re-established, and every two to three years, a caravan with about 200–300 camel loads of ivory, leather-skins, and some slaves reached the port of Benghazi. But external threats to Wadai primarily from as a result of raids on its caravans from northern nomadic groups such as the Tubu and Fezzan-Arab groups who blocked northern routes beginning in 1842, an action that likely involved the Jallaba trading diaspora, forcing al-Sharif to reinstate the anti-northern policies of his predecessors by imprisoning and executing northern caravan traders, such that Wadai was effectively cut off from the northern markets. (explaining the "xenophobic" reputation of the kingdom which Nachtigal claimed characterized al-Sharif's reign)33

Trade was gradually revived under Mohammed al-Sharif's successor king Ali who encouraged Kanuri and Hausa merchants from the west to trade with Wadai, and was also closely associated with the Jallaba traders from the east through his wife. Despite king Ali's best efforts however, Wadai's northern route wouldn't be re-opened until 1873 when the first caravan arrived, and it wasn't until the 1890s that northern trade reached its apogee with 17 caravans with 548 tonnes of merchandise departing for Abeche in 1893-1894, and a Sanussi representative named Mohammed al-Sunni, being permanently stationed at the Wadai court to handle the Sanussiya's trade with Wadai. By 1907, 20% of Benghazi's ,£240,000 imports and 33% of its £304,000 of exports were for Wadai, an earlier estimate in 1873 placed the value of Wadai's trade with Benghazi at 16,700 MTT (less than £1,000) showing its dramatic rise. The bulk of this trade was in ostrich feathers, ivory, indigo-dyed cloth, leather-skins, and slaves, the latter of whose share of trade was declining as their demand had all but ended by their ban in most of the Ottoman markets by then.34

In the late 19th century, Benghazi was exporting 700 slaves a year and retained 200 locally, all of whom were obtained from the routes through Wadai and the Fezzan35, (which was a relative small trade at the time compared to the Atlantic slave ports36). Given the highly irregular nature of the Wadai-Benghazi route, its status as the only remaining route after the 1870s in which all the northern-directed slave export trade was confined (after the closure of both the Bornu route through Tripoli, and the Mahdist-Sudan trade to Ottoman-Egypt), and considering the tribute of slaves that Wadai collected form vassals like Bagirmi, it's unlikely that any significant fraction of the export traffic came from Wadai itself.37 The majority of captives (who were a secondary effect of war) were likely retained locally, as there are several slave officials who appear within the Wadai administration in the 19th century where they held positions of influence, as well as in the military as soldiers directly under the King.38

A large caravan with over 600 camels near Kufra in the 1930s. located in south-eastern Libya, Kufra was home to a major Sanussiya lodge in the late 19th century39

The fall of Wadai (1898-1912)

The last decades of Wadai's history were spent in the shadow of the looming threat from the advancing French colonial forces that had colonized Bagirmi in 1898, and Kanem in 1901, chipping away Wadai's power. Before the appearence of the French, Wadai's King Yusuf (r. 1874-1898) had managed to preserve the kingdom's influence in its eastern frontier throughout several upheavals in which DarFur was conquered by the Ottoman-Egyptians (1874), who were inturn overthrown by the Mahdists (1881) that were inturn overthrown by the reestablished kingdom of DarFur (1898) just before his death. Yusuf's foreign policy with the Mahdi was particularly antagonistic, and culminated with Wadai’s conquest of several former Mahdist vassals in the south-east40

Letters written by Wadai king Yūsuf ibn Muḥammad Sharīf in 1891 and 1895, addressed to his various dependencies in Sudan. (Durham University Library Archives, Reginald Wingate’s collections)

States on south-eastern border of Wadai that were brought under its control by King Yusuf

Yusuf's son Ibrāhim (r. 1898-1900) was installed by the royal council that had initially considered him the easiest of the candidates to control, until he turned against them and in the ensuing revolt with the nobility, he was deposed by internal factions backed by the re-instated king of DarFur Ali Dinar41, and replaced by Ahmad Abu Ghazali (r. 1900-1901) who was also eventually caught up in internal strife, that ended with the ascendance of Muhammad sālih (known as Dud Murra), the last king of Wadai (r. 1901-1911). Dud Murra restored central control in Wadai and revived its regional trade with Darfur kingdom until relations with the latter deteriorated in 1904-542, Dud Murra expanded his arsenal of firearms through his Sanussiya connections and ivory trade, in preparation for the inevitable war with the French.43

Initial attempts by Wadai to take back its southern territories of Kanem and Bagirmi from the French in 1904-5 were reversed, and the French then went on the offensive in 1906-7 using the pretext of installing a pretender named Asil in favor of Dud Murra, they skirmished with the latter’s provincial forces but didn't face the bulk of army that was concentrated in the south-eastern regions.44 After two battles in 1908-9 however, the French captain Fiegenschuh defeated Wadai's provincial forces and entered Abeche, but Dud Murra had fled the capital, meeting Fiegenschuh's forces outside in Jan 1910 where he annihilated them and killed their captain. This forced Fiegenschuh's commander; colonel Maillard, to attack with his own men in November 1910, but they too were defeated by Dud Murrah's cavalry forces and all were killed -making Dud Murrah a widely disdained figure in the French press. It wasn't until October 1911 that another French force managed to force Dud Murrah to surrender, and permanently occupied Wadai in 1912, marking the end of west Africa's last independent kingdom.45

illustration in a French newspaper of the armies of Dud Murra made in February 1911, shortly after the wadai sultan had defeated the French in December 1910.

Horsemen of Wadai

Conclusion: the view of Trans-Saharan trade from Wadai

The history of Wadai allows us to better understand pre-colonial African societies within their context. Despite Wadai’s prominent position in the discourses which overstate the role of external trade in the formation of African states, the available research on the kingdom’s history overturns these simplistic causative arguments. The growth of Wadai, and its peers in the eastern Sudan "was not dictated by the exigencies of long-distance trade"46; Wadai had reached its apogee long before king Sabun pioneered the kingdom’s direct access to Mediterranean markets, but even this access was never consistently maintained, as it was routinely closed due to internal factors in Wadai and because external trade was relatively trivial to Wadai's economy which was primarily dominated by domestic exchanges between its Sahelian and Saharan groups.

Rather than ‘living and dying’ by Trans-Saharan trade, Wadai flourished by exploiting the diverse geographic and ecological environment in which it was established. In contrast to its peers who were marginally engaged in long-distance trade, Wadai was firmly situated within its local geographic context at the edge of the Sahara; the desert kingdom of Africa.

Abéché, 1920

Despite its reputation as the world’s most inhospitable region, the Sahara desert was not a formidable barrier between North-Africa and “Sub-Saharan” Africa as its often presented. Read about the history of the Kanem-Bornu empire’s conquest of southern Libya on Patreon

<subscribe to my Patreon for this and more indepth research on African history>

The Oxford Handbook of Ancient Nubia By Bruce Williams pg 895, 900-901

The Oxford Handbook of Ancient Nubia By Bruce Williams pg 902-903

Kingdoms of the Sudan by RS O'Fahey pg 115-116

The Cambridge History of Africa, Vol. 4 pg 137-138, UNESCO General History of Africa, Vol. V pg 511

Sahara and Sudan by Gustav Nachtigal pg 165-171

Des pasteurs transhumants entre alliances et conflits au Tchad by Dangbet Zakinet 109-112)

Sahara and Sudan by Gustav Nachtigal pg 180

Des pasteurs transhumants entre alliances et conflits au Tchad by Dangbet Zakinet 81-84, for a similar position of ‘Arabs’ in various parts of the central and eastern sudan see; Ethnoarchaeology of Shuwa-Arab settlements by Augustin Holl.

Des pasteurs transhumants entre alliances et conflits au Tchad by Dangbet Zakinet pg 75-79,

Conservation et valorisation du patrimoine bâti au Tchad : cas des ruines de Ouara by Eric Bouba Deudjambé pg 28-37, Travels of an Arab merchant in Soudan by al-Tunusi 1954, pg 126-129

Arabic Literature of Africa, Volume 2. pg 426-432

Travels of an Arab Merchant in Soudan pg 250

Sahara and Sudan IV by Gustav Nachtigal pg 189

A Political History of the Maba Sultanate of Wadai by Jeffrey Edward Hayer pg 15-16)

Kingdoms of the Sudan by RS O'Fahey pg 128)

A Political History of the Maba Sultanate of Wadai by Jeffrey Edward Hayer pg 16, 69, Des pasteurs transhumants entre alliances et conflits au Tchad by Dangbet Zakinet pg 120-122)

A Political History of the Maba Sultanate of Wadai by Jeffrey Edward Hayer pg 16, State and Society in Dār Fūr By Rex S. O'Fahey pg 78)

Society in Dār Fūr By Rex S. O'Fahey pg 82, A Political History of the Maba Sultanate of Wadai by Jeffrey Edward Hayer pg 17

The Cambridge History of Africa, Vol. 4 pg 141)

State and Society in Dār Fūr by Rex S. O'Fahey pg 85)

Sahara and Sudan IV by G. Nachtigal pg 216-217, A Political History of the Maba Sultanate of Wadai by Jeffrey Edward Hayer pg 23-25)

Sahara and Sudan IV by G. Nachtigal pg 220-226, A Political History of the Maba Sultanate of Wadai by Jeffrey Edward Hayer pg 30-39 )

State and Society in Dār Fūr by Rex S. O'Fahey pg 147, Cows and the sharīʿah in the Abéché Customary Court by Judith Scheele pg 31

The Cambridge History of Africa, Vol. 4 pg 141)

A Political History of the Maba Sultanate of Wadai by Jeffrey Edward Hayer pg 39

Sahara and Sudan by Gustav Nachtigal pg 195-196

Sahara and Sudan IV by Gustav Nachtigal pg 119

Mahdish Faith & Sudanic Traditio By Kapteijns pg 199,173

Sahara and Sudan IV By Gustav Nachtigal pg 214 n3, but other dependencies were likely no more than a few dozen, Mahdish Faith & Sudanic Tradition By Kapteijns pg 111-112

Des pasteurs transhumants entre alliances et conflits au Tchad by Dangbet Zakinet pg 81-88, Sahara and Sudan by Gustav Nachtigal pg 182

Eastern Libya, Wadai and the Sanūsīya by Dennis D. Cordell pg 22-23)

Eastern Libya, Wadai and the Sanūsīya by Dennis D. Cordell pg 29)

Across the Sahara by Klaus Braun pg 156, Eastern Libya, Wadai and the Sanūsīya by Dennis D. Cordell pg 24, Sahara and Sudan IV by G. Nachtigal 43, 49, 136)

Eastern Libya, Wadai and the Sanūsīya by Dennis D. Cordell pg 21,30 Across the Sahara by Klaus Braun pg 158-160)

The Trans-Saharan Slave Trade by John Wright pg 111-112

Slave Traders by Invitation by Finn Fuglestad pg 96

The Trans-Saharan Slave Trade by John Wright pg 105, 124 Across the Sahara by Klaus Braun pg 229

A Political History of the Maba Sultanate of Wadai pg 84, Des pasteurs transhumants entre alliances et conflits au Tchad by Dangbet Zakinet pg 76-77

Across the Sahara by Klaus Braun pg 52

Mahdish Faith & Sudanic Traditio By Kapteijns pg 107-113

An Islamic Alliance: Ali Dinar and the Sanusiyya, 1906-1916 By Jay Spaulding pg 12-13

An Islamic Alliance: Ali Dinar and the Sanusiyya, 1906-1916 By Jay Spaulding pg 20-21

A Political History of the Maba Sultanate of Wadai by Jeffrey Edward Hayer pg 39-41

A Political History of the Maba Sultanate of Wadai by Jeffrey Edward Hayer pg 42-43

The Roots of Violence: A History of War in Chad By M. J. Azevedo pg 51-52

State and Society in Dār Fūr By Rex S. O'Fahey pg 147

Hi thank you so much for writing about my culture, I didn’t even know most of these things!! May god bless you

I want to learn about the transatlantic slave trade from the African side. I am a black American and I need to know. Yes, I Need to know.