The history of the Hausa city-states (1100-1804 AD): Politics, Trade and Architecture of an African mercantile culture during west-Africa's age of empire.

an African urban civilization

Hausa language, civilization and culture are all intertwined in the term Hausa, first as a language of 40 million people in northern Nigeria and west Africa and thus one of the most spoken languages in Africa, second as a city-state civilization; one with a rich history extending back centuries and found within the dozens of city states in northern Nigeria (called the Hausalands) that flourished from the 12th to the 19th century characterized by extensive trade, a vibrant scholarly culture and a unique architectural tradition. Lastly as a culture of the Muslim and non-Muslim populations of northern Nigeria and surrounding regions, these populations included traders, scholars, religious students and the Hausa diaspora in north Africa, west Africa (from the upper Volta region of Ghana to Cameroon) and the Atlantic world. 1

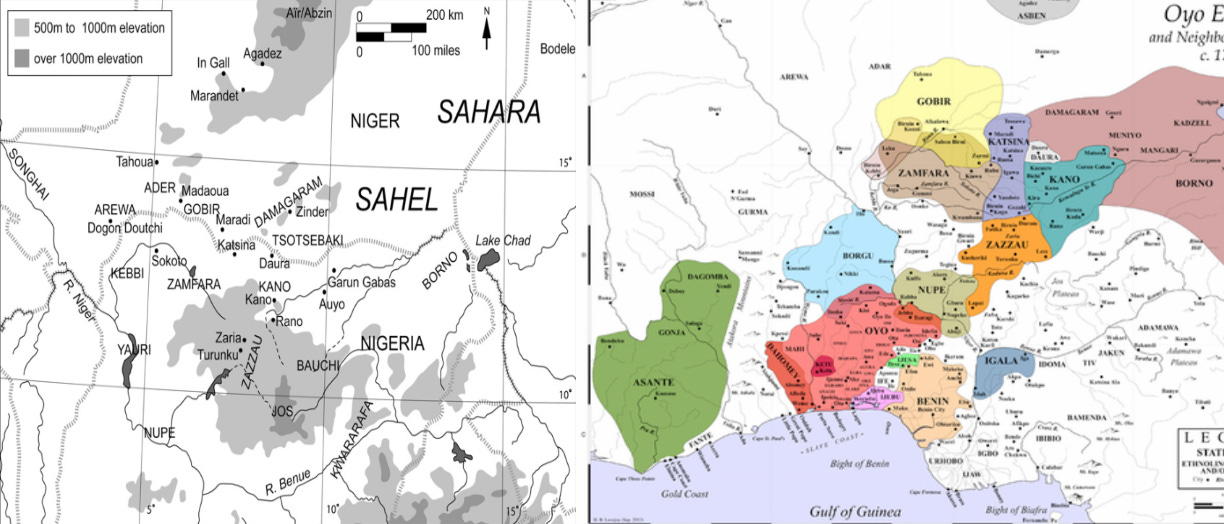

The formative period of state formation in the Hausalands begun in the 12th century with the appearance of the city walls of Kano and the 13th century burials at Durbi Takusheyi. The process of state building and political consolidation of various chiefdoms into large kingdoms in the Hausalands culminated with the emergence of seven “prominent” city states; Kano, Daura, Gobir, Zazzau, Katsina, Rano and Hadeija, along with the "lesser" states; Kebbi, Zamfara, Nupe, Gwari, Yauri, Yoruba (Oyo) the latter of which comprise both Hausa and non-Hausa populations. This process became enshrined in the Hausa origin myth; the so-called Bayajida legend which is a sort of Hausa foundation charter repeated in oral and written history that links the dynasties of the seven Hausa city-states.

Gold earrings, pendant, and ring from Durbi Takusheyi, Katsina State, Nigeria (photo from NCMM Nigeria)

According to the Bayajida legend, a price from the east married a princess from Bornu and the queen of Daura both of whom gave birth to the seven rulers of the seven Hausa cities, he also had a concubine who gave birth to the rulers of the "lesser" states. Interpretation of this allegory is split with some historians seeing it as a reflection of the embryonic Hausa polities2 while others consider the Bornu (empire) elements of the story as an indication of Bornuese influence on early Hausa state formation3 or even outright concoction by Bornu by legitimizing the latter’s imperial claim over the Hausalands,4 while the narrative of seven founding rulers has parallels in several African Muslim societies like the Swahili and Kanem.

Owing to their position between the storied empires of the “western Sudan” and “central Sudan” ie: the Mali and Songhai empires to its west and Kanem-Bornu empire to the east, the Hausa developed into a pluralistic society, assimilating various non-Hausa speaking groups into the Hausa culture; these included the Kanuri/Kanembu from the 11th century (dominant speakers in the kanem-bornu empire), the Wangara in the 14th century (Soninke/Malinke speakers traders from the Mali empire), the Fulani in the 15th century, and later, the Tuaregs, Arabs, Yoruba and other populations5. It was within this cosmopolitan society of the Hausalands that the Hausa adopted, innovated and invented unique forms of social-political organization especially the Birni -a fortified city which became the nucleus of the Hausa city-states.6

Birni Kano in the 1930s, Nigeria (photo by Walter Mittelholzer)

Support AfricanHistoryExtra by becoming a member of our Patreon community, subscribe here to read more about African history, download free books, and keep this newsletter free for all:

By the mid-15th century the Hausa urban settlements had developed into large mercantile cities commanding lucrative positions along the regional and long distance trade routes within west Africa that extended out into NorthAfrica and the Mediterranean, transforming themselves into centers of substantial handicraft industries especially in the manufacture of dyed textiles and leatherworks, all of which were enabled by a productive agricultural hinterland that supported a fairly large urban population engaged in various specialist pursuits and other groups such as scholars, armies (that included thousands of heavy cavalry), large royal households in grand palatial residences and vibrant daily markets where all articles of trade were sold.

A Brief overview of Hausa political and military history

maps of the hausalands and the surrounding states in the 16th-18th century

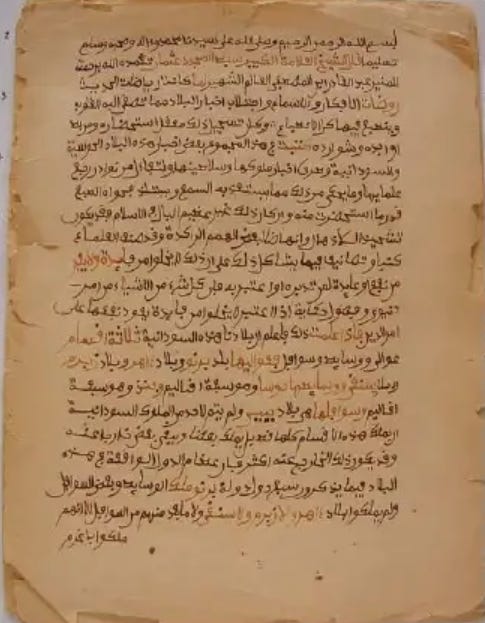

Hausa Historiography

Most of Hausa history is documented in the various chronicles, king lists and oral traditions of the city-states that were written locally, most notably the Kano chronicle, the Katsina chronicle, the song of Bagauda, the Wangara chronicle, and the Rawdat al-afkar. Its from these that the early Hausa history has been reconstructed. Although much of the information contained in them relates to the three of the most prominent city-states of Kano, Katsina and Zaria, with only brief mentions of Gobir, Kebbi, Daura and other city-states.

Rawdat al-afkar (The Sweet Meadows of Contemplation) written by Dan Tafa in Salame, Nigeria. 1824

Early Hausa (from the 10th to 13th century)

The establishment of early Hausa societies was characterized with expansion and consolidation, first with an expansion from their core area west of lake chad then followed by an expansion from the northwest to the south east region of central Nigeria7. This non-deliberate expansion involved both diplomacy and warfare. At this stage, the polities were small chiefdoms which would later be consolidated as kingdoms such as at bugaji and durbi in Katsina, at dala in Kano and at karigi and gadas in Zaria. During this period, a common designation of Hausa was unknown and the people that came to refer to themselves as Hausa/Hausawa were only referring to themselves by the distinct states of which they belonged.8 During this period, the embryonic Hausa polities were protected from the two west African powers of Mali and Kanem-Bornu that would feature prominently in the later centuries. It was also during this time that the Hausa first appear in external sources with the first mention of Kebbi by Arab historian Al-Idrisi (d. 1165AD) which he calls Kugha9

An old section of kano’s city wall

Middle period (from the 14th-mid 16th century

The formative period ended by the late 14th century by which time, the Hausa city-states had been firmly established, with their fortified capitals, royal dynasties and trade routes now in place. The borders of each city-state then begun to meet and with them, their armies which then set off a series of extensive military campaigns and aggressive expansion beyond their borders directed against other Hausa city-states and non-Hausa states alike.

In Kano, this expansion begun with the reign of Sarki (king) Yaji (r. 1349-1385AD) who attacked Rano in 1350 and clashed with the Jukun of Kwararafa (these later featured prominently among the non-Hausa foes). These campaigns were continued by Sarki Kananeji (r. 1390-1410AD) during whose reign the Wangara, who'd come from Mali under his predecessors' reign, now became prominent at Kananeji's court; introducing the mailcoat armour, iron helmets and quilted armor for cavalry (this unit of the army would became central to warfare in the Hausalands and apart of Hausa culture). Prosperity set in with the reign of Sarki Rumfa (r. 1463-1499AD) who is credited with several political and social innovations in Kano such as the Kano state council, the extension of the city walls and construction of the largest surviving west African palace, it was during this time that the scholar Al-Maghili (d. 1505AD) briefly resided in the city.10

Gidan Rumfa, the 15th century palace built by Sarki Rumfa in Kano, Nigeria

In Zazzau (which often referred to by its capital: Zaria), this phase of expansion begun during the reign of Sarki Bakwa in the 15th century who consolidated his kingdom later than his peers and established his capital at Turunku, north of the city of Zaria, the latter city was built by his daughter named Zaria and later became the capital of the city-state. Bakwa’s more famous daughter, Amina, is noted for campaigning extensively to the south, warring against the Nupe and kwararafa and reportedly reaching as far as the Atlantic ocean. Her conquest of kwararafa cut off Kano's source of wealth albeit briefly11 and she is purported to have subjected neighboring Hausa states to tribute and extended the city walls of Zaria and the walls other towns in the kingdom, of which she is personified. Writing in 1824, the historian Dan Tafa says this about her:

"the government of Zaria was the kingdom of Amina the daughter of the Amir of Zaria, who made military expeditions throughout the lands, Kano and Katsina were subject to her. She made military expeditions throughout the lower Sudan, until she reached the encompassing ocean to the south and west but she didn't conquer any part of the upper sudan"12

A section of Zaria’s walls and one of its gates in the 1920s (photo from quai branly)

In Katsina, this phase of expansion was initiated by Sarki Muhammad Korau (d. 1495AD) who extended the walled city, subjected neighboring chiefs to tribute and expanded his territory southwards campaigning against Kano and the Nupe. He is credited with the construction of the katsina palace, the Gobarau mosque and minaret and receiving various scholars from both west and north Africa including the abovementioned Al-Maghili13

A section of Katsina’s walls in the 1930s (photo from quai branly)

West-African empires in the Hausalands (1450 to 1550AD)

During the mid 15th century, west African imperial states were reorienting their political and trade centers which brought them closer to the Hausalands, this reorientation begun in the east of the Hausalands with the empire of Kanem-bornu that was shifting its capitals west of lake chad to the region known as Bornu, later establishing its capital at Ngazargamu in the 1480s, while to the west of the Hausalands, the songhai empire in the late 15th century which had its capital at Gao, was starting to campaign closer to the Hausalands. The most important political turning point was the flight of a deposed Mai (emperor) of Bornu named Othman Kalnama to Kano between 1425-1432AD, he brought with him clerics, who greatly augmented the nascent scholarly community in Kano, Othman was briefly left in charge of administering Kano by Sarki Dawuda (r. 1421-1438 AD) while the latter was out campaigning. This action attracted the attention of the Bornu emperors and beginning with Mai Ibn Matala (r. 1448-1450 AD) imposed an annual tribute on Kano, along with the city-states of Daura and Biram.

Section of the Old palace at Daura

Between 1512-1513 AD, the Songhai emperor Askiya muhammad (r. 1493-1528 AD) launched a war east to the Hausalands, allying with Zaria and Katsina to attack Kano which he took, and later seized the former two as well. Songhai's domination of the three principal Hausa cities was short-lived lasting until around 1515AD around the time when the Askiya attacked the Tuareg capital of Agadez, among his generals in this battle was Kotal Kanta who was later disappointed with his treatment by the Askiya and revolted, defeating a Songhai army sent to crash his revolt in 1516AD, Kanta then set about establishing his own empire whose capital was at the city of Kebbi, he conquered the Hausa city-states previously taken by Songhai and briefly ruled the entire Hausalands (Kano, Gobir, Katsina, Daura, Zaria, etc) and built another walled capital at Surame. This state of affairs lasted until his death in 1550AD allowing two of the principal Hausa city-states of Kano and Zaria to re-assert their independence from all three imperial states (Bornu, Songhai and Kebbi), these two were later joined by Katsina and Gobir in 1700AD, this independence continued well into the 18th century.14

Late period (from the mid 16th to late 18th century)

This was the golden age of the Hausa city-states, with increasing trade contacts particularly with the Gonja region of northern Ghana for kola nuts, gold dust and the rapid expansion of the local textile industry with the signature indigo-dyed cloths of Kano now serving as currencies in much of the region. There are a number of notable political events during this time such as the wars between Katsina and Kano from the late 16th and early 17th century that intensified during this time as each sought to upend the other's prominence. These interstate wars never led to the definitive conquest of one city-state over another despite either states often sieging the city-walls of their foes15. The Hausa city-states also saw increasing attacks by the Jukun of Kwararafa which overturned their previously subordinate relationship with Kano, Zaria and Katsina and inflicted devastating defeats on all three and took plunder, although not reducing them to tributary status, these Jukun also attacked the Bornu empire but were defeated at their siege of Ngazargamu in 1680AD breaking their military power and ending their attacks against the Hausalands.16

During this period, there was struggles for power between the Sarki and the electoral council that saw oscillating periods of increasing and decreasing centralization of political authority in Kano, while in Zaria, a protracted civil war had ended with a political settlement, this period was also marked with increasing cosmopolitanism and growth of the Hausa scholarly communities. Katsina finally upended Kano's trade prominence after the latter's economic downtown caused by an inflation in cowrie shell money and heavy taxation of traders and city-dwellers alike, the latter of which had been introduced by Sarki Sharefa (r. 1703-1731 AD) and forced many traders to flee from Kano to Katsina, swelling the latter's population. In the early 18th century, the rising power of Gobir brought it into contact with Kano, with the former increasingly attacking the latter but never defeating it, they later both came under Bornu’s suzerainty in the 1730s but the wars between the two continued well into the century.17

In the 17th century, Kano and Zaria had a population of around 50,000 people, and later In the 18th century, Katsina attained a peak population of 100,000.18 these two had became arguably the most important trading cities in west Africa following the decline of Timbuktu and Jenne and were now well known in external documentation as well, as noted by Italian geographer Lorenzo d'Anania (d. 1609AD) who described Kano, with its large stone walls, as one of the three cities of Africa (together with Fez and Cairo) where one could purchase any item.19

Kano’s dye pits in the 1930s (from quai branly)

Throughout this period, the pluralist Hausa city states maintained an equilibrium between the largely muslim oriented urban population and the traditionalist rural hinterland within the capital's control, but the increasing power of the muslim scholarly community in the late 18th and early 19th century across westAfrica tipped the scales against the traditionalists whose authority declined along with the pluralist states that they influenced. This started in Futa Jallon in 1725 AD and continuing into the mid 19th century and resulted in a number of old west African states being toppled; in the Hausalands, this movement was led by Uthman dan Fodio between 1804-1810 AD, who subsumed the Hausa city-states under the Sokoto empire ending their centuries-long independence beginning with Kebbi in 1805AD. Many of the deposed Hausa sovereigns would go on to form independent city-states north and south of the Sokoto empire such as Maradi and Abuja, the latter of which is now the capital of Nigeria.20

the 19th century palace at Maradi

Trade and economy in the Hausalands

The Hausa city-states had substantial economic resources and were at the center of strategic trade routes which, added to their competitive city-state culture enabled them to grow into the trading emporiums of west Africa from the mid 16th to the late 19th century. Central to this prosperity was the agricultural productivity of the cities’ hinterlands particularly Kano and Katsina, which controlled a bevy of smaller towns and villages within their respective states (such as Dutse and Rano in Kano city-state) that paid tribute in various forms and supplied the city's markets with agricultural produce, supporting their large urban populations and enabling the growth of several industries and specialist crafts the list of which includes dyed textiles, leatherworks, smithing, tanning, construction , copyists, and carpentry, among others.21

Of the local manufactures, Hausa crafts-workers produced both for sale at the local market and for the royal court, the crafts industries particularly metal-works, leather-works and textile-works were regulated through appointed crafts heads. With metal-works, most of the smiths worked to supply the local market with the various articles of metal purchased for household use, among these the most famed were the Takuba swords made by Hausa smiths and used across the central region of westAfrica, these smiths were exempted from taxes but instead being tasked with making the weapons and armor needed for warfare. The leatherworkers and tanners produced the shields and quilted armor for the royal court and also sold footwear, leatherbags, waterskins, book covers, saddles and other leather goods in the local markets.

Hausa leather shoes and sandals, inventoried 1899 at quaibranly

Textile workers such as dyers and embroilers were the biggest industry among the Hausa cities, cotton was grown in surrounding towns and villages in the Hausalands and brought to the cities, where thousands of weavers worked with treadle looms to make cloths, dyers dipped these cloths in indigo pits and embroiderers added unique geometric patterns to each robe. Cotton was grown in the Hausalands as early as the 10th-13th century with textile production and dyeing following not long after, by the 15th century textile production and cotton growing had already come to be associated with the Hausa cities as noted by historian leo Africanus in 1526 AD who wrote about the abundance of cotton around Kano and Zamfara22.

embroidered Hausa cotton robes inventoried in 1886 at quaibranly

The textile dominance of the Hausa was such that from the 18th century, most of the central and western Sudan (from Senegal through Mali, Niger and northern Nigeria) was clothed in trousers, robes and shirts made in the Hausa cities, as noted by the explorer F. K. Hornemann in the 1790s, every item of Tuareg attire was manufactured in the Hausa cities.23 Initially, textile production and trade in the Hausalands was dominated by the Wangara and the Kanuri both for clothing and partially as currency but both were supplanted by the local Hausa producers in the 16th century and as currency by the 18th century.

The signature indigo dyed cloths of the Hausa made in dye pits that dotted sections of the city were well established by the 16th century, and Hausaland exports begun reversing the flows of cloth trade such that Kano and Katsina begun exporting to Bornu, to the formerly wangara-dominated western Sudan, and to the Tuaregs.24

Hausa embroiderer, Northern Nigeria 1930s

External (caravan) trade came through three main routes with one running north from/through Agadez, another running east from/to Ngazargamu, and one coming from the west to/from Gonja and the Asante (see map for these regions). This caravan trade was well regulated with an official responsible for their accommodation and supply who directed them to hostels and other lodging places where a host/broker would help them conduct their trade, change their currencies and provide credit among other things.25

Hausaland imports included manufactures such as paper, luxury cloth, muskets, gunpowder, steel blades and cloth (which mostly came from north Africa and the Mediterranean), and commodities such as salt from the Saharan fringes (controlled by Bornu and the Tuaregs), kola nut and gold dust the upper-volta region (controlled by Dagbon and Gonja) and cowrie shells from the yorubalands (controlled by Oyo and Nupe), the most lucrative of these routes was the western trade with Gonja which brought in kola nut and gold dust, and where Hausa traders were active as early as the 15th century during Sarki Yakubu's reign (r. 1452-1463 AD).26

Hausaland Currencies

The Hausa city-states used various forms of currencies, primarily; gold dust, cowrie, cloth strips and the thaler coins. Gold dust was used not long after the establishment of the trade route to Gonja in the 15th century , from where it was exported north and used also used as a medium of exchange.27

Cowries arrived in the hausalands in the 16th century, initially from trans-saharan routes dominated by Songhai and Bornu, they were first introduced in Kano, and soon after in Katsina, Zamfara, Gobir and other Hausa cities as well. While the cowrie inflation that was associated with Sarki Sharef came from those cowries introduced via the southern (Atlantic) sources with more than 25 tonnes of cowries being brought into Gobir from the Nupe between 1780-1800 AD.28

The use of cloth strips as currency proliferated during the 17th century across the “central sudan” region, they were made to be uniform in size, weave and dye and were primarily produced in Kano, Zaria and Rano which were best suited for cultivation of cotton and indigo, the price of the cloth currency varied seasonally and corresponded with its value as clothing.29

Hausa Architecture

Hausa architecture's design is uniquely local in origin but also incorporates construction methods found within the wider west-African “sudano-sahelian” architecture. The Hausalands contain some of the oldest architectural monuments in west Africa, including the oldest surviving west African palace; the Gidan Rumfa and Gidan Makama (both built in the 15th century by Sarki Rumfa of Kano), the oldest surviving city walls and gates; the walls and gates of Kano built between the 12th-15th century, and the unique innovation of constructing vaulted ceilings and domed roofs with mudbrick, a difficult feat only attested in few societies such as ancient Nubia and the Near-eastern civilizations.

gidan makama, the first palace of Sarki Rumfa built in the 15th century

House facades in kano (photos from the mid 20th century)

Primary materials for construction were sun-dried conical mudbricks called tubali, palmwoods such as Hyphaene thebaica and Borassus aethiopum called ginginya/garuba and a select type of swamp and earth clay that was used for mortaring and plastering called tabo, kasa. Most Hausa monuments such as the city walls, palaces and mosques were built by professional masons; architects/master-builders who belonged to crafts-guilds, technical expertise was acquired by students through an apprenticeship of at least ten years under a successful master where they were first taught the making of tubali bricks, then taught plastering, exterior decoration and constructing walls, and lastly taught how to construct vaulted roofs and ceilings.30 The explorer Hugh Clapperton met such a Hausa architect in 1824, most likely the famous Muhammadu Dugura, who built the domed Zaria mosque in the mid 19th century.31

interior and exterior of the mosque of Zaria built in 1832 in typical Hausa style

the 19th century palace at Dutse

Conclusion: the Hausa as an African urban civilization

Hausa cities belonged to a type of state system that is often overlooked in discourses on African history in favour of large territorial empires. such African city-states include the Swahili, the Yoruba, the Banaadir and close to a dozen others that traded, warred and competed with each other to grow into what were arguably the most dynamic and cosmopolitan African urban settlements. Characterized by significant handicraft manufacturing bases, large markets and pluralist societies, and whose prosperity attracted traders, scholars and imperial powers alike. These cities provide us with an understanding of Africa’s economic history and their assimilationist cultures offer an alternative form of social organization which was uncommon in the pre-modern era.

for more on African history, Free book downloads and ancient African astronomy, subscribe to my Patreon account

Being and Becoming Hausa by A. Haour, pgs 5-12

Towards a less orthodox history of Hausaland by J. Sutton, pg 195-199)

Some considerations relating to the formation of states in Hausaland by A. Smith pg 336)

The affairs of Daura by M.G Smith pg 56

UNESCO General History of Africa, Vol. IV by D. T. Niane pg 112

A. Smith pg 338-345)

A. Haour pg 48

The Beginnings of Hausa Society by M.G.Smith, pg 342-345

A. Haour pg 9

Government in kano by M.G.Smith, pgs 116-121, 129-136

M.G.Smith pg 124)

Translation of the Rawdat al-afkar by muhammad sheriff

D.T.Niane, pg 108

M.G.Smith, pg 137-141

A Comparative Study of Thirty City-State Cultures by M. H. Hansen, pg 500-501

M.G.Smith, pg 162

M.G.Smith, pgs 168-172

3000 Years of Urban Growth by T. Chandler, pg 47

A. Haour pg 10

Jihād in West Africa during the Age of Revolutions by P. E. Lovejoy

D.T.Niane, pg 116

Cloth in west african history by C. E. Kriger, pg 78

The Desert-Side Economy of the Central Sudan by P.E.lovejoy, pg 555

A. Haour, pg 193-194

M.G.Smith, pg 41-42

M.G.Smith pg 128

Timbuktu and the Songhay empire, J.Hunwick, pg xxix

The shell money of the slave trade by J. S. Hogendorn, pg 104-105)

M.G.Smith pg 23

maximizing mud by by S.B. Aradeon, pg 206)

Hausa Urban Art and Its Social Background by F. W. Schwerdtfeger pg 109

I'm a history student, and currently, your article is what's helping me for my assignment study. It is, for sure, a very lucrative, self explanatory and elaborate one as well. Thank you 🥂