The invention of writing in an African kingdom: a history of the Bamum script (1897-1931)

"Our memories are fallible. We need a way to keep the word, in a way that it will speak for us, even in our absence"

Shortly before the turn of the 20th century and the dawn of colonialism, a ruler of a kingdom in western Cameroon's grassfield's region received a vision in which he was instructed to write. This ruler, who went on to become a renowned scholar and renaissance man, invented a unique script that would create one of the most dynamic literary traditions in west Africa.

For over 30 years, the kingdom of Bamum was the site of one of west-Africa's most remarkable intellectual revolutions. Sheltered from the direct effects of colonialism by its shrewd ruler; king Njoya, a literary tradition emerged that produced thousands of works in the Bamum script, from official correspondence, to educational literature, to epics and judicial proceedings, the writing system of king Njoya permeated all facets of Bamum society.

This article outlines the political and social context in which the Bamum script was invented, exploring the rapid evolution of the script through six stages, and the formation of a unique literary tradition in western Cameroon.

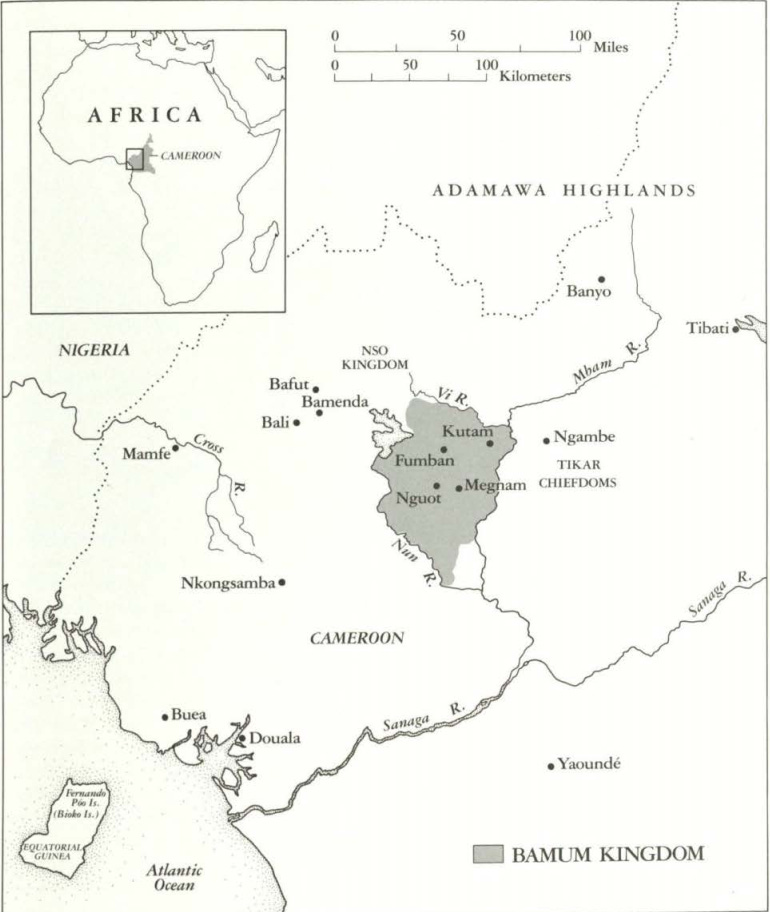

Map showing the Bamum kingdom in the late 19th century

Support African History Extra by becoming a member of our Patreon community, subscribe here to read more about African history, download free books, and keep this newsletter free for all:

A political history of the Bamum kingdom until king Njoya’s reign

The Bamum kingdom was established between the late 16th and early 17th century by king Nchare, a prince of the ruling dynasty in the chiefdom of Tikar, to the east of the Mbam River, and founded the capital of the kingdom at Fumban.1 The kingdom, which was largely comprised of Bamiléké and Tikar speaking groups (both members of the Bantu language family)2, gradually expanded across the region, subsuming smaller polities in western Cameroon. Bamum was at its peak in the early 19th century under king Mbuombuo (r. 1757–1814) who greatly expanded the kingdom over neighboring chiefdoms and took their insignia which became important objects in royal iconography of Bamum.3 He also successfully defended the kingdom against an invasion from a cavalry army of the Pa'arë4, distributed endowments of lands and subjects among the members of the patrilineages, and the kingdom’s expansion was consolidated by his successor Nguwuo (r. 1818–1863). While a succession crisis ensued upon Nguwuo’s death, the kingdom was restored after the ascendance of king Nsa’ngu (1863–1887), who managed to consolidate his power for a while, afterwhich he went to war with Nso’ kingdom in the north, which ended with a disastrous loss and his death.5

King Njoya ascended to the throne soon after his father's death in 1889 but since he was only 12yrs old at the time, his early reign was initially under the regency of the queen-mother Shetfon, Njoya's mother Njapndunke, and the Palace officer Titamfon Gbetnkom Ndombuo. All of whom were shrewd regents that secured Njoya's position against many rivals, until he was able to ascend to rule on his own after 1892.6

But soon after taking full control of the throne, Njoya had to contend with a rebellion started by the former Palace officer Titamfon and the kingdom descended into civil war. In 1895, Njoya decided to form an alliance with Lamido Umaru of Banyo (1893-1902), a provincial governor of the Adamawa emirate of Sokoto. Lamido’s armies were invited into Fumban by 1897 and quickly put down the rebellion, securing Njoya's throne.7

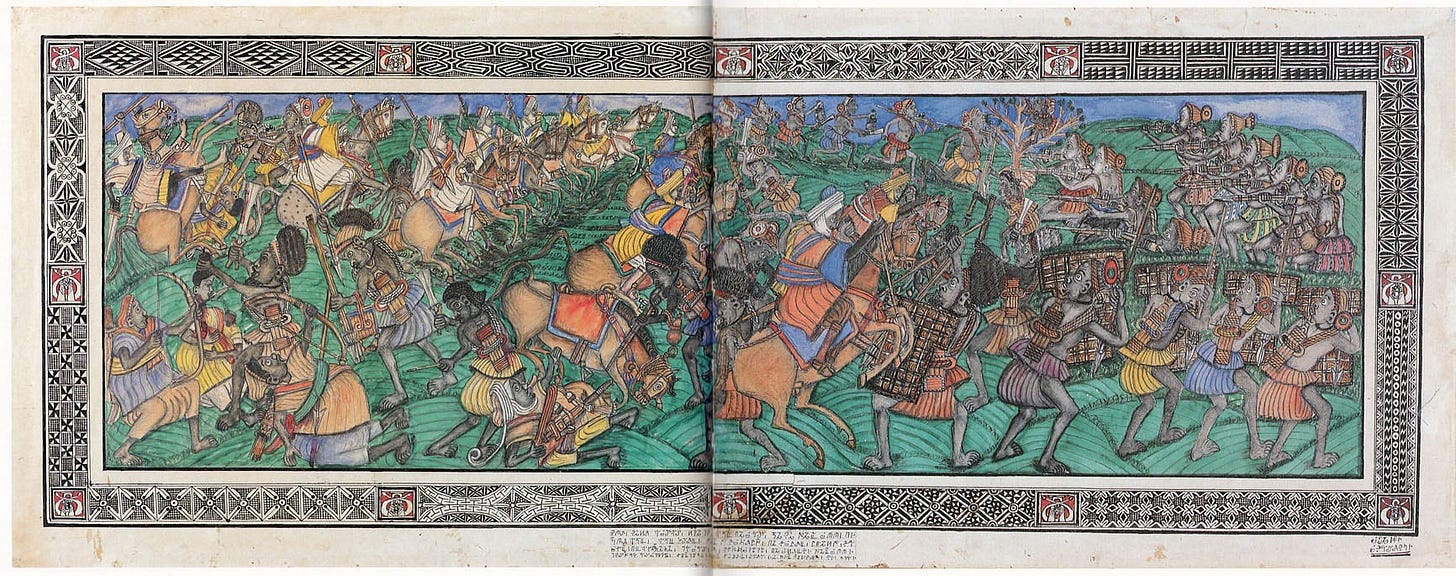

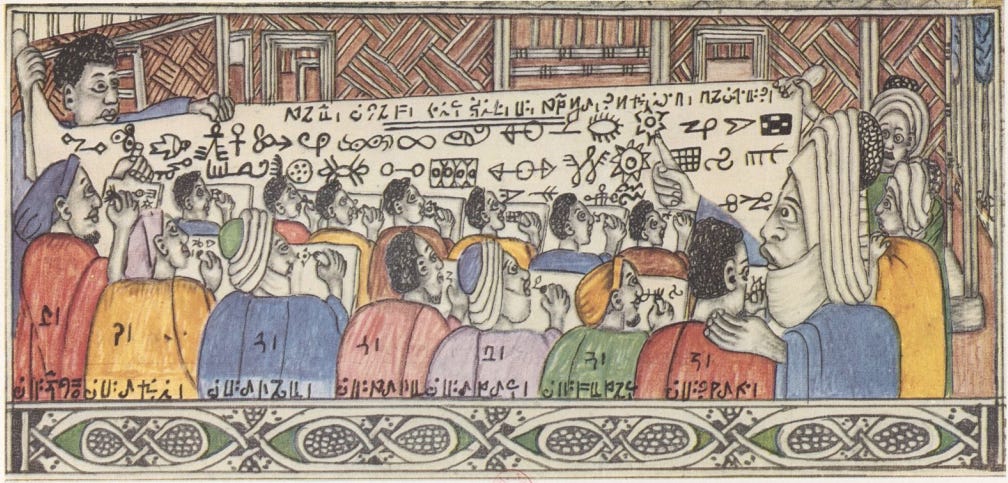

an early 20th century illustration by a Bamum artist depicting the invasion of Bamum by cavalry armies of the Pa'arë.

an early 20th century illustration by a Bamum artist depicting the civil war of the late 19th century at Fumban and the alliance between Adamawa and Bamum to secure Njoya’s throne. (Musée d'ethnographie de Genève Inv. ETHAF 033558)

Njoya had been impressed by the fighting efficiency of Lamido's cavalry which was instrumental in the civil war, which in Bamum was remembered as the ‘victory of the horse’, but even more memorable were the Adamawa force's pre-battle customs of (Islamic) prayer and protective talismans , which was similar to Bamum's own pre-battle customs of taking "war medicine", and upon witnessing the success of Adamawa's "war medicine", the king and his courtiers decided to adopt Islam inorder, albeit superficially.

As one Bamum chronicle about the conversion of Njoya described;

"Njoya decided to take some war medicine from the Fulbe so as to increase the Bamum territory like his predecessor King Mbombwo had done. This was reported to the Sultan of Banyo who sent to the sultan Njoya a large white gandoura, a long turban, a pair of baggy trousers and prayer beads and then told him to pray to God, as it was out of this prayer that the war medicine would come. From then on Njoya started the practice of Moslem prayers, not in the name of God but as a war medicine" 8

Njoya's court thus adopted some external attributes of the power from Adamawa following a secular and coherent internal logic, that included the adoption of Islam from Hausa marabouts, the wearing of long costumes and amulets, as well as marks of precedence (music, griots). Njoya's court demonstrated a renewed interest in the copies of the Koran that had been circulating in Fumban since the reign of King Nsangu, and initiated the construction of mosques.9 Nevertheless, the influence of Njoya's newly-found Muslim allies was largely restricted to the royal sphere, and was confined to a few superficial attributes.

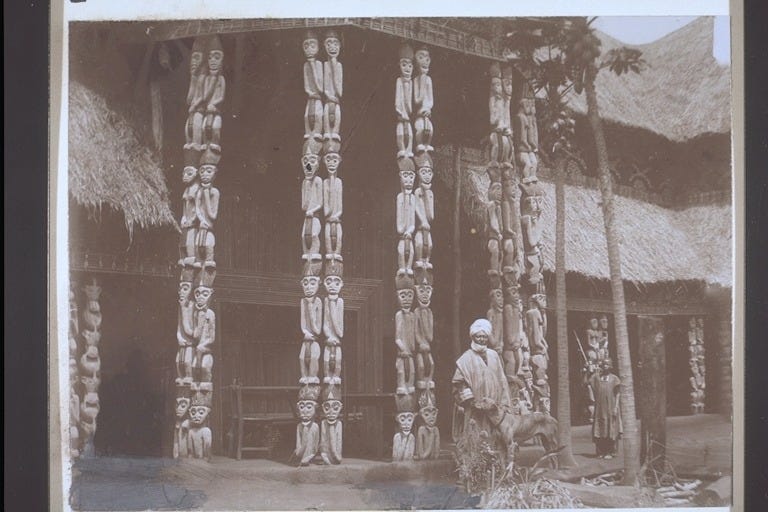

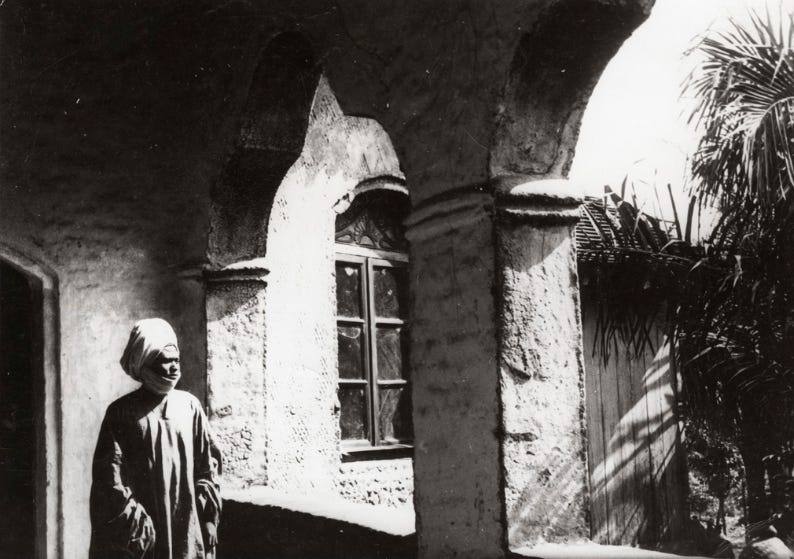

Gate to Fumban, ca. 1920, (defap library)

Njoya in front of his old palace at Fumban, 1907, (basel mission archives)

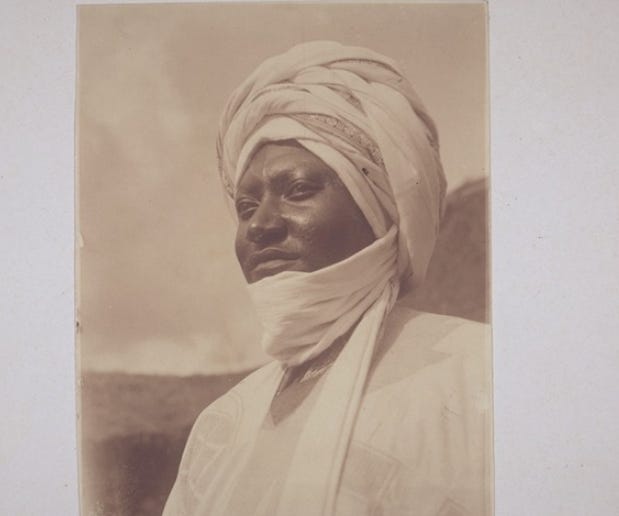

King Njoya of Bamum, 1911, (basel mission archives)

The impetus for inventing a script

Political status and prestige were central to the development of Bamum script. King Njoya was inspired to create writing after a revelatory dream. In Njoya’s retelling, a teacher instructed him to draw an image of a hand on a wooden tablet before washing it off and drinking the water10. According to this same account;

"the king called many people and told them; 'If you draw a lot of different things and name them, I'll make a book that speaks without being heard – What good is it said people, whatever we do we will not succeed” The king himself had made trials on his side. He called Mama and Adzia to come and help him compare the work that had been done on both sides. Five times the king tried, but in vain, to obtain a result; it was the sixth successful attempt. The writing was found"11

This imagery related in the Bamum script's invention is largely similar to the well-established memorizing and healing practices across much of Islamic societies in africa from west africa to sudan. These practices, called "drinking" the Qurʾan involve the writing of Quranic versus on wooden slabs using homemade ink that is fabricated with water, gum arabic, and charcoal, that is then washed off with water to be consumed by the student (for memorizing) or patient (for mild illnesses).12

Such practices were sufficiently familiar to non-Muslim West-African communities such that even the inventor of the Medefaidrin script in south-eastern Nigeria, had a similar inspirational vision which led him to believe that by drinking water he would “receive knowledge washed from a great book written in different colored inks and thus receive the words of God”.13

The Bamum script’s evolution (1897-1910)

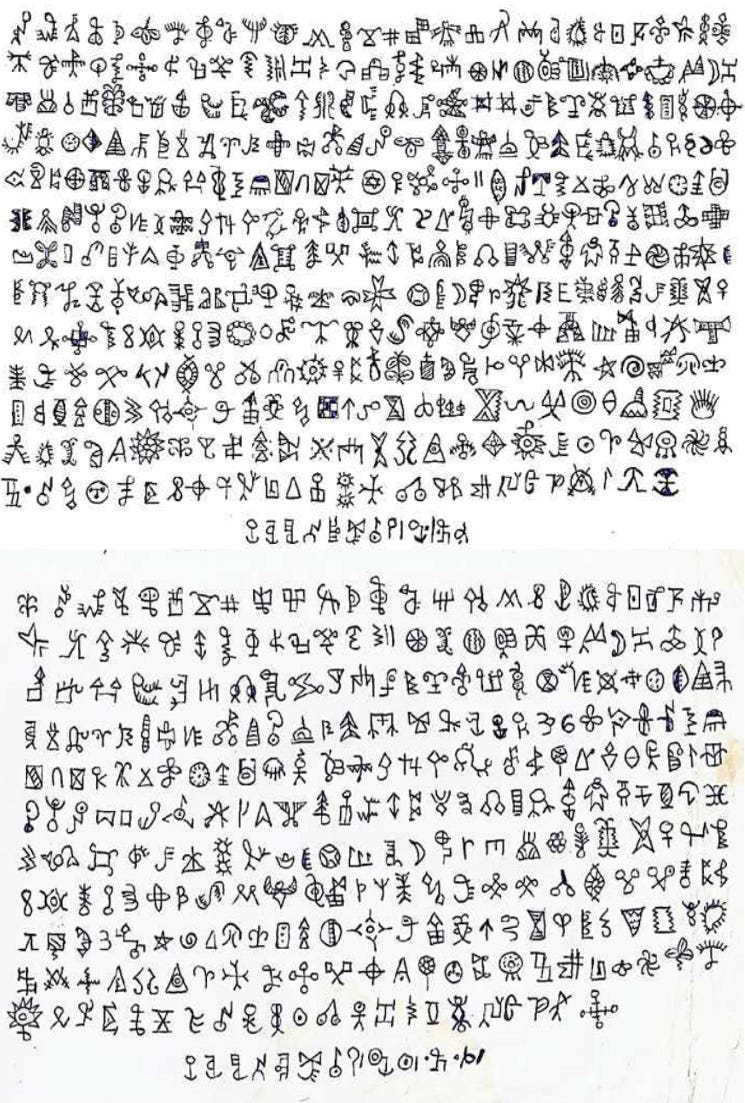

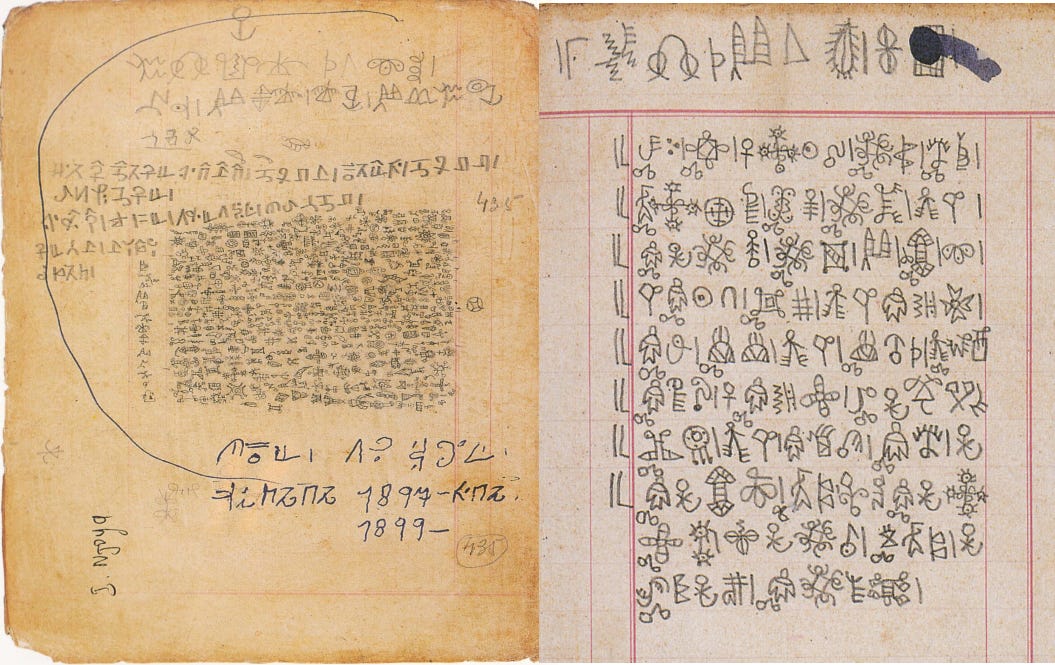

Prior to his first encounter with Adamawa elites, Njoya had begun work on a local script for his native language of Bamilike14. With assistance from at least two of his royal advisors; Nji Mama Pekekue and Adjia Nji-Gboron, king Njoya drafted the first version of the Bamum script, which was called “Lerewa”/”Lewa” and was completed around 1897. With its 700 ideograms and pictograms that represented real objects and actions, Njoya's logographic script, was wholly unlike the consonantal Arabic script used by his newly-found Muslim allies, nor the alphabetic Latin script that was creeping into his kingdom ahead of the approach of the colonial armies.15

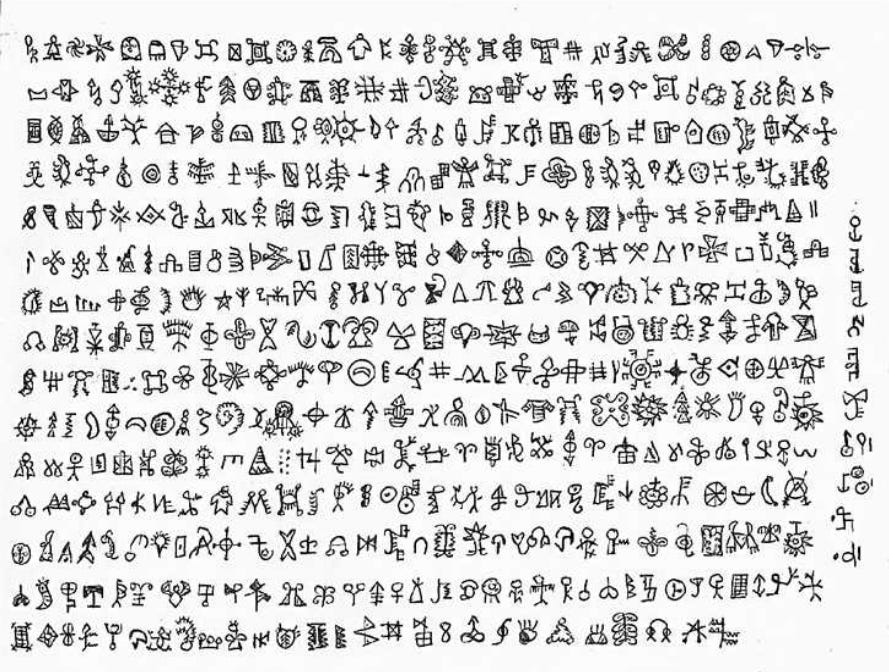

“Lerewa”, the first version of the Bamum script developed around 1897.

some of the major categories of signs in “Lerewa”

The corpus of symbols used for "lerewa" were drawn from the vast iconographic corpus appearing across Bamum's material culture, presented to Njoya by his courtiers. Each of these courtiers proposed symbols from their immediate environment and professional field. The main register came from the richly patterned Ndop textiles, besides these; musicians proposed in priority drawings of musical instruments, the blacksmiths brought symbols from their equipment, and horse-riders drawings of animals. The original 700 characters were eventually brought down to 500 and then to 465, the script was written in all directions , further differentiating it from neighboring scripts.16

Ndop textiles from Fumban, early 20th century, (Portland museum, Michael C. Carlos Museum). This form of textile pattern was also reflected in Bamum’s architecture shown below, and appears in some of the symbols in “Lerewa” above.

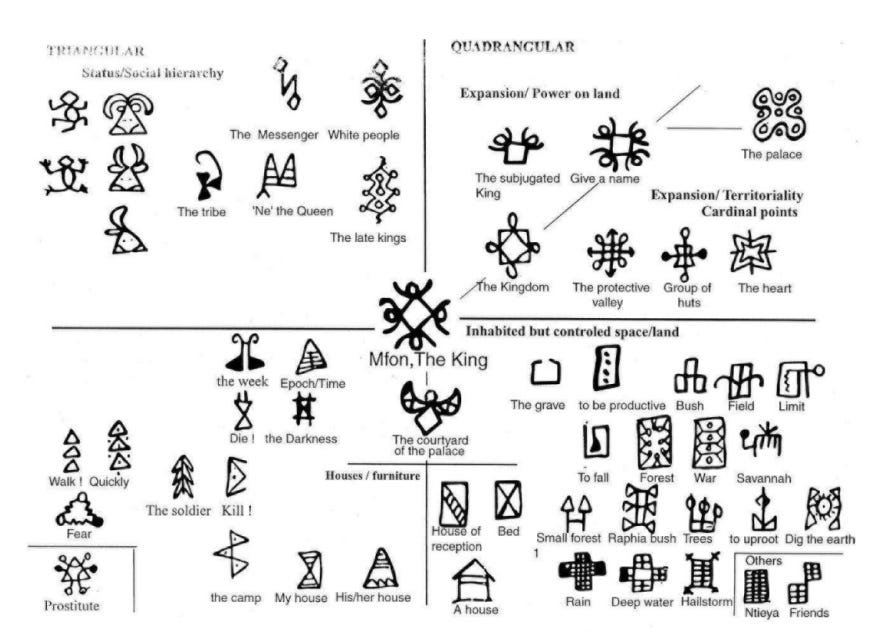

architectural drawing by Ibrahim Njoya showing the Layout of the old palace of Fumban, with writings in Bamum script, ca. 1927, private collection17. (photo above it is from the defap library)

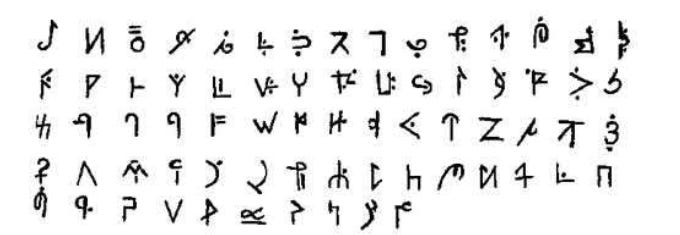

After the end of the civil war, Njoya begun modifying Lerewa, eliminating many characters and introducing a few new symbols bringing the total down from 465 to 437, to end up with a new version that he named “Mbimba”, which means; mixture in Bamilike18 The script was at this stage, transitioning from a logography to a logo-syllabary, in an evolution similar to that followed by the Vai script of Liberia.

“Mbimba”, the second version of Bamum script developed around 1899-1900

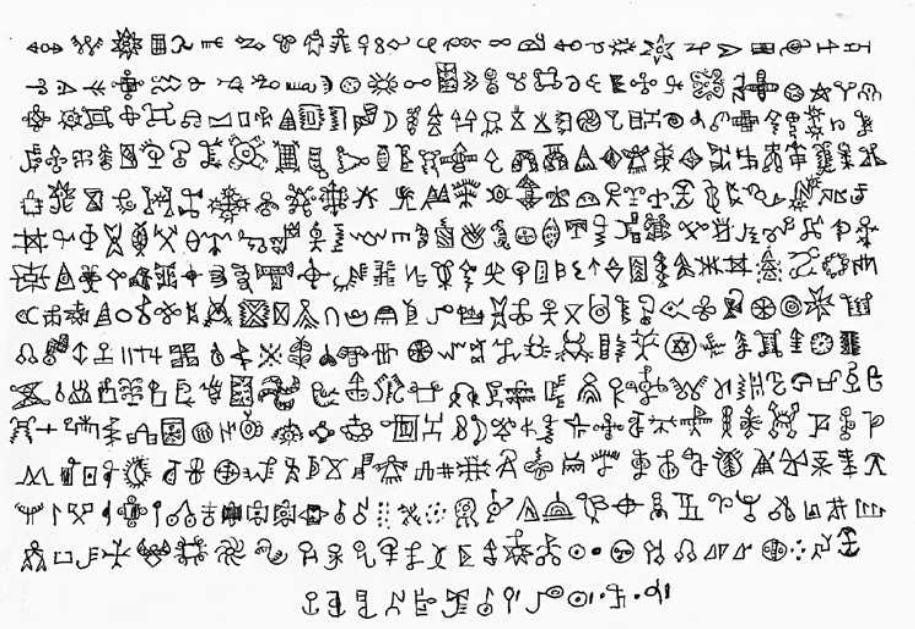

Beginning in 1902, Njoya further transformed the script to create the third version; called “nyi nyi nʃa mfɯˀ” which represented a true syllabary script. The total inventory of characters was reduced from 437, to 381. He later reduced the characters from 381 to 286, in the fourth version called “rii nyi nʃa mfɯ” in 1907, and from 286 to 205 in the fifth version called “rii nyi mfɯˀ mɛn” in 1908, and finally to the standardized version of the Bamum script called “A ka u Ku” in 1910, with its 80 characters.19

Two types of; “Nyi Nyi Fa Fu” and “Ri Nyi Fa Fu” from 1902, and 1907.

The final, standard version of the Bamum script/“A ka u Ku”.20

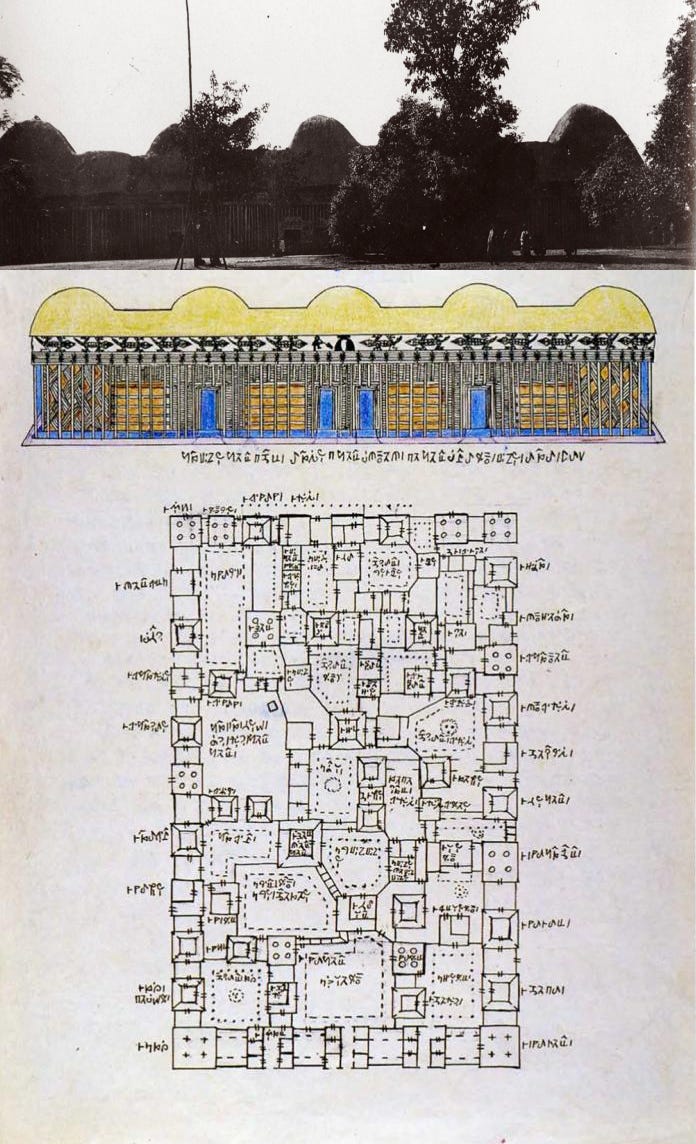

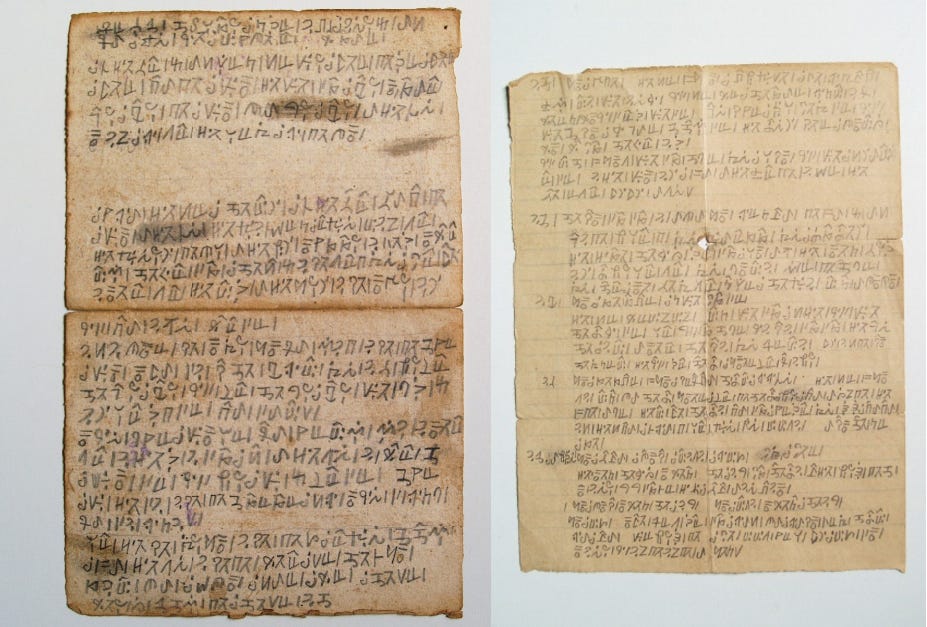

Bamum manuscripts written in the first version of the script, the first one dated in 1897 is credited to King Njoya while the second is credited to his similarly named cousin Ibrahim Njoya

Creating an intellectual revolution in Bamum

The originality of King Njoya's approach in inventing the script was enabled by political will, the mastery of the instruments of power and the speed of his reaction to external stimuli within the rapidly evolving political landscape that Bamum was thrust in the early 20th century. This included the arrival of the German colonial forces in 1902, with whom Njoya negotiated with to retain his kingdom as a semi-autonomous colony21, the establishment of a (Christian) mission school in Fumban in 1906 in which Njoya was actively involved but wasn't converted, and the defeat of the Germans by allied armies in 1916 afterwhich Bamum fell on the French half of the Cameroon colony.22

To promote the use of the script, Njoya founded his own school at the palace in 1898, modeled after Quranic and mission schools, where princes and noble servants were instructed in Bamum writing.23 Njoya began offering formal classes in Bamum history and the Bamum script to both male and female students drawn from leading Bamum families. As these pupils became more adept in the use of script, they were tasked with helping to spread it further by teaching in the growing number of Bamum schools established around the kingdom. By 1918 there were 20 different schools across the kingdom serving more than 300 students, increasing the number of subjects literate in the Bamum script from an estimated 600 in 1907 to over 1,000 by the early 1920s.24

Njoya designed a professionalized teaching system. Formalizing the different subjects to be taught in his schools in which students were awarded diplomas signed by their teachers and the king himself. The major school division/"department" heads (besides history, religion, cartography and art which Njoya and many of his courtiers took up for themselves) included Medicine, calligraphy, carving and casting, weaving, and other crafts which were essential in Bamum's domestic economy; with students often writing down their work using the Bamum script.25

Njoya’s later Palace, completed in 1922 after his first palace had burned down. (Defap library)

King Njoya's school in Fumban, 1905, (basel mission archives)

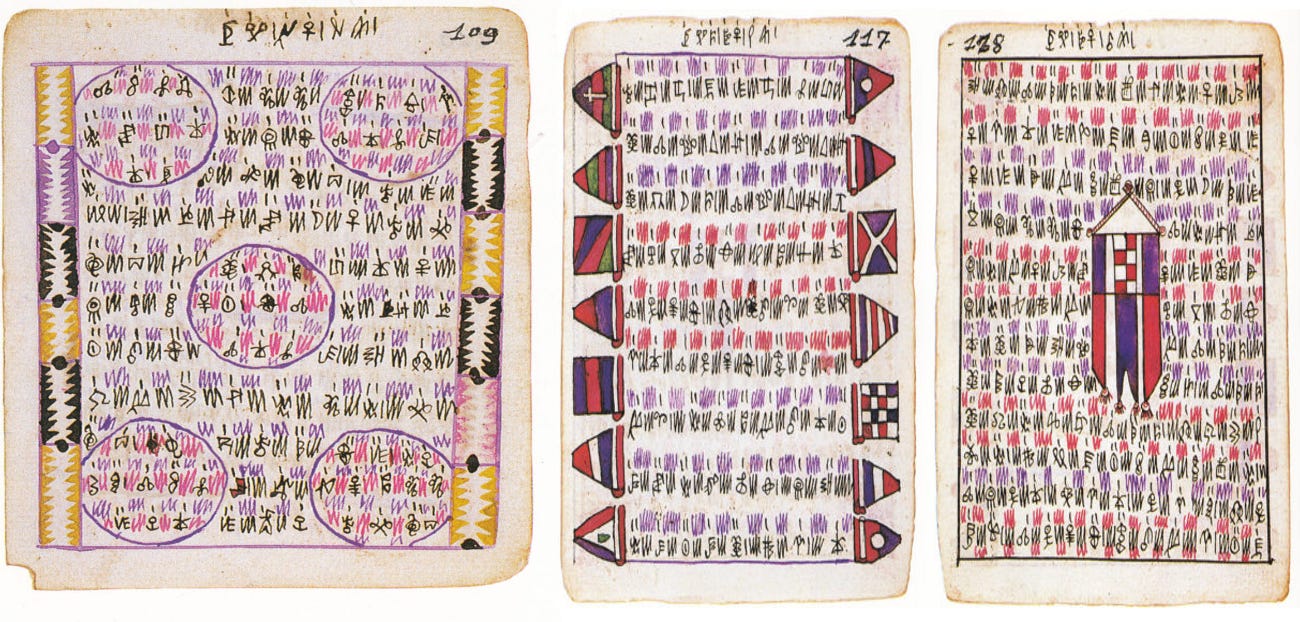

Njoya furthered the spread of the script by writing many books (Libonar), including chronicles about the Bamum kingdom’s history such as the 548-page “Libonar Oska” (The History of the Laws and Customs of the Bamum in 191226) , instructional texts specifying the hierarchy of signs in Bamum metaphysics such as “Libonar Da Lerewa Njuem” (book of interpretation of dreams27), pharmacopeia such as “Libonar Pu Lewa fu nzut fu libok” (the book of healing remedies, written in 190828), others include fables, descriptions of Bamum customs, and books about the syncretic religion Njoya invented named "nuǝt nkuǝtǝ" (Pursue to Attain, written 1916).29 He also invented a "royal" version of the Bamum script called shü moum in the late 1900s for the exclusive use of palace officials. His courtiers and officials also began to keep Judicial records, maps30, landsales, births, deaths, and marriages in the Bamum script.31

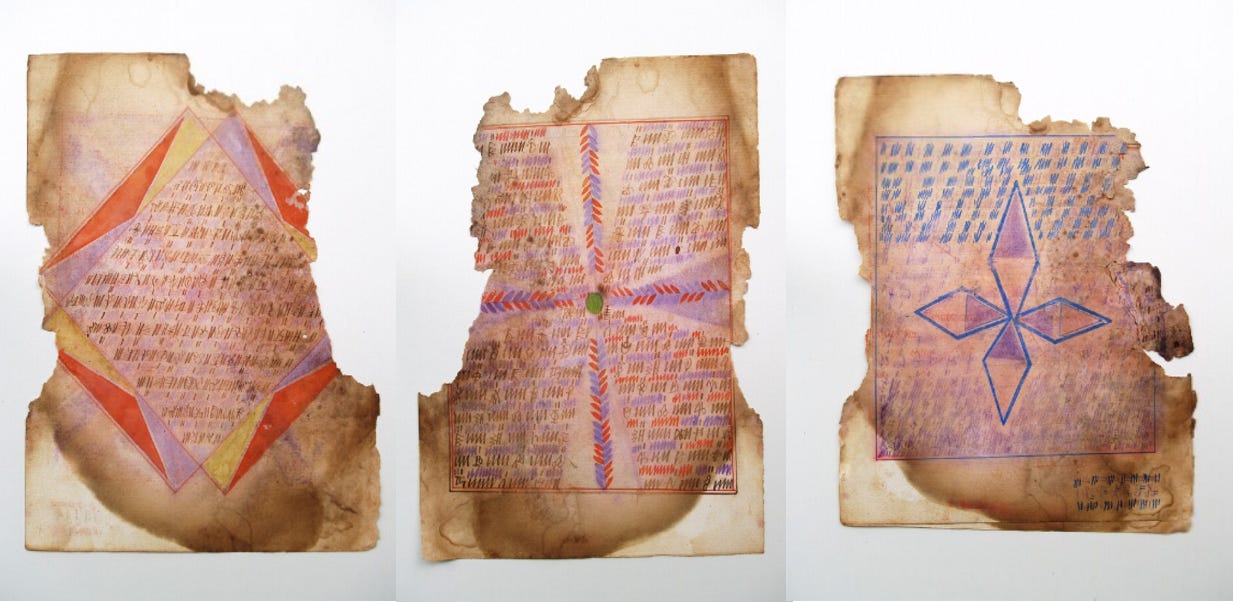

various folios from Njoya’s religious book; “nuǝt nkuǝtǝ”, private collection32

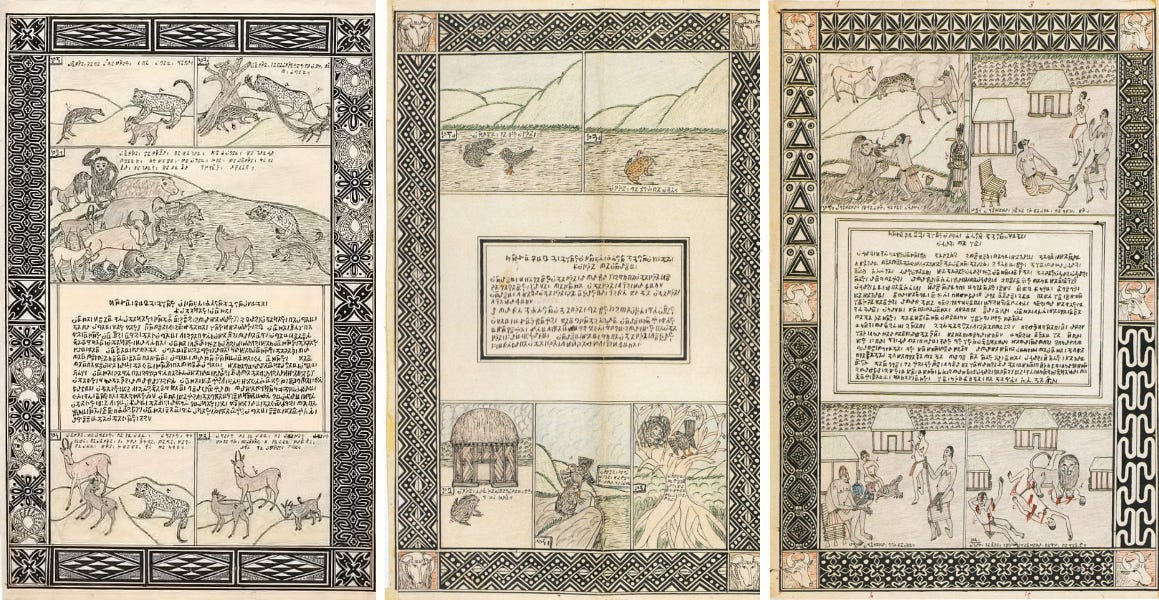

Storyboards with illustrations drawn by Ibrahim Njoya showing various fables from Bamum; The Tale of the Leopard and the Civet, Tale of the Frog and the Kite, Tale of Mofuka and the Lion. (Musée d'ethnographie de Genève Inv. ETHAF 033557)

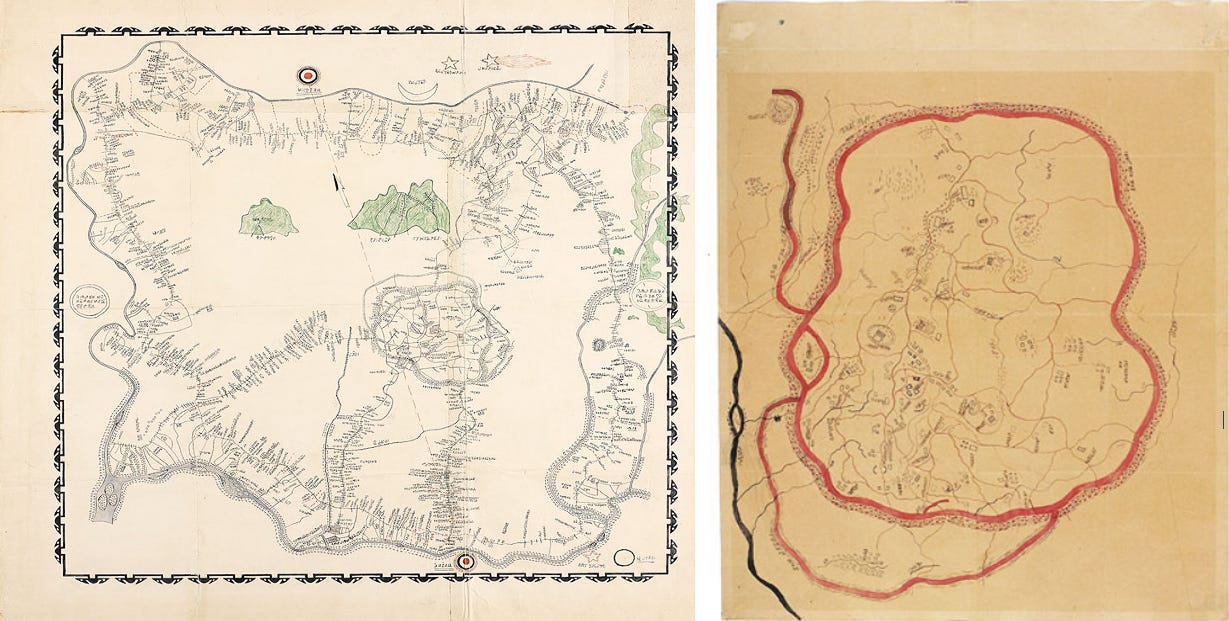

Map of Bamum kingdom, Map of its capital Foumban, drawn by Ibrahim, 1920-1930, with notes in Bamum script specifying the organization of space and the world. (Musée d'ethnographie de Genève Inv. ETHAF 033553, ETHAF 023023)

To further increase the pace of producing Bamum language texts, in 1913 Njoya approached the German administrator at Fumban about developing a printing press for his script, When the Germans failed to respond, he commissioned his favorite craftsman named Kpumie Pinu, (who had made him a corn mill earlier on), to cast the printing press which the latter eventually accomplished after a great effort. Unfortunately, the printing press took nearly 7 years to complete and by the time it would have been operational, Njoya was deeply embroiled in political conflict with a rival contender to the Bamum throne named Yeyap, who was inturn allied with the French colonial administration. For this reason, the printing press, along with many other initiatives by Njoya, were the causalities of this conflict, with the king being forced to destroy it shortly after completion in 1920.33

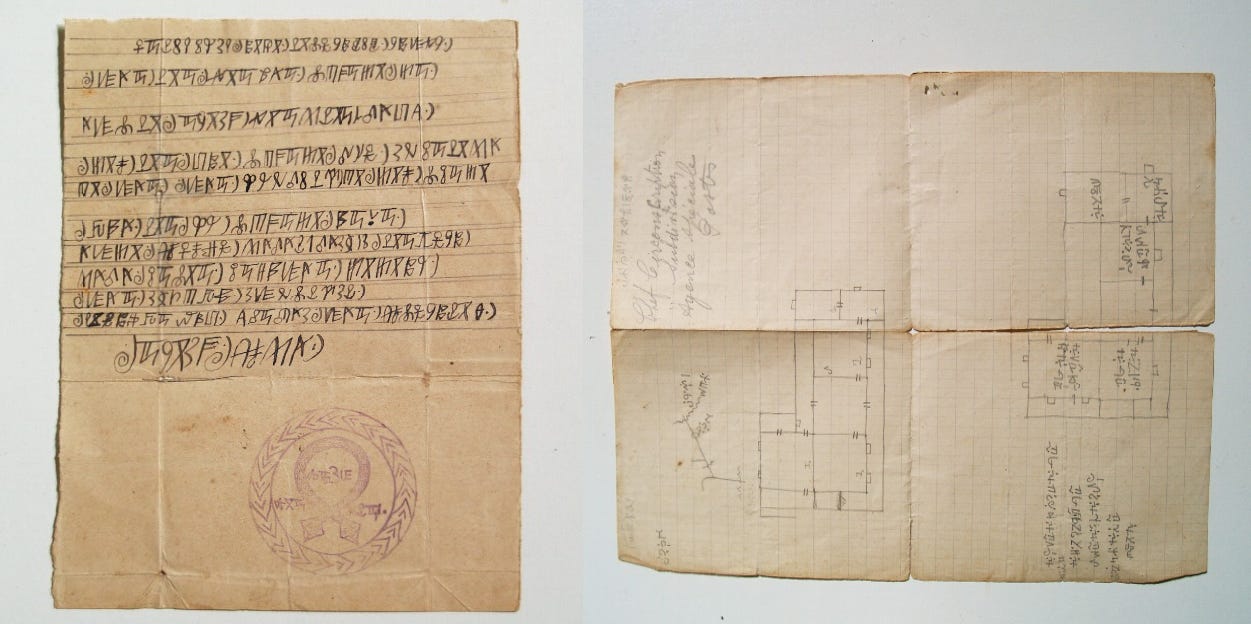

Chronicle of the Bamum kingdom, written in 1900, Archives du Palais des Rois Bamum, Fumban, Cameroon34

Note on the Trial of the case of Monta and Shikue, written in 1910, Archives du Palais des Rois Bamum35. Plan with architectural designs for the construction of a house with proportions labeled in Bamum script, written in 1910 Archives du Palais des Rois Bamum.36

Instructions on various medicinal remedies for removing poison from the body, written around 1945, Archives du Palais des Rois Bamum.37 Treatise on Protective Medicines to guard against Leprosy and Small Pox, written around 1910, Archives du Palais des Rois Bamum.38

Colonial policy and the end of the Bamum script.

The growing French colonial government's hostility to Njoya beginning in 1919, started undermining the kingdom's semiautonomous status by ending its tribute system, and creating various titled governors within the kingdom that answered to the colonial government at Yaounde rather than the king at Fumban, persistently challenged royal authority. While Njoya made all efforts to prove as adaptive to the French rule as he had to the Germans, including constructing a large palace in 1922 that doubled as a museum inorder to store books written in the Bamum script and showcase Bamum's art and rival Yeyap's own museum39, the colonial administration increasingly saw Njoya and his schools, as an impediment to their political objectives of ; direct rule, the use of French (and its Latin script), and assuming full economic control of the colony. With a decline in Njoya's political power as his kingdom was divided, and declining financial capacity to support the propagation of the script, enrollment in Bamum script schools gradually declined over the 1920s as students moved to colonial schools, such that by 1930, one administrator mentioned that the Bamum script "was no longer used except by the sultan and his courtiers”.40

Njoya in his Palace, ca. 1925 (defap library)

Njoya’s power was rapidly curtailed and reduced, he was forced to cut his palace administration by 1,127 in 1920, forced to cease the collection of tribute which was replaced by a meager salary from the colonial government that had placed Bamum’s provinces under their control in 1924, and had his craftguild removed from the palace in 1927.41 When the king learned that the French had killed their own king in 1789, he became convinced that their continued comments about limiting royal power in Bamum were simply a prelude to his eventual destruction.42 After a number of rebellions by some of his subjects to restore Njoya's power, the king was arrested by the colonial government and sent into exile in Yaoundé, where he died two years later on May 30, 1933. The Bamum script was only saved from near extinction in 1985 when a school teaching it was reopened by king Njoya's successor Seidou Njimoluh. Beginning in 2005, the over 7,000 Bamum documents held in the palace of king Njoya were digitized and are currently available online.43

Illustration from 1938, king Njoya teaching the Bamum script to members of his court

The NSIBIDI script of south-eastern Nigeria is west-africa’s oldest indigenous writing system, read about its invention and see some Nsibidi manuscripts written in cuba in the 19th century.

Peoples of the Central Cameroons part 9 by Merran Mcculloch

Linguistic Survey of the Northern Bantu Borderland: Volume Two By Irvine Richardson

Le Royaume Bamoum by Claude Tardits pg 110,112

Les invasions Pa'arë ou Baare-Tchamba et l'émergence du royaume bamoun au XIXe siècle by Eldridge Mohammadou

African Crossroads: Intersections Between History and Anthropology in Cameroon by Ian Fowler pg 142-144)

Images from Bamum : German colonial photography at the court of King Njoya by Christraud M. Geary pg 16)

Fulani Hegemony in Yola (Old Adamawa) 1809-1902 By M. Z. Njeuma pg 36-37)

African Crossroads: Intersections Between History and Anthropology in Cameroon by Ian Fowler pg 145)

De l'iconographie à l'écriture, première analyse du système graphique bamoun by Galitzine-Loumpet pg 2)

The Invention, Transmission and Evolution of Writing by Piers Kelly pg 194

De l'iconographie à l'écriture, première analyse du système graphique bamoun by Galitzine-Loumpet pg 3)

The Walking Qur'an: Islamic Education, Embodied Knowledge, and History in West Africa by Rudolph Ware pg 57-58)

The Invention, Transmission and Evolution of Writing by Piers Kelly pg 194)

Le roi Njoya: créateur de civilisation et précurseur de la renaissance africaine by L'Harmattan pg 243-244

Njoya’s Alphabet by Kenneth J. Orosz pg 46

De l'iconographie à l'écriture, première analyse du système graphique bamoun by Galitzine-Loumpet pg 7-9, Le roi Njoya: créateur de civilisation et précurseur de la renaissance africaine by L'Harmattan pg 244

Art, Observation, and an Anthropology of Illustration by Max Carocci pg 88

Le roi Njoya: créateur de civilisation et précurseur de la renaissance africaine by L'Harmattan pg 248-249

The Invention, Transmission and Evolution of Writing by Piers Kelly pg 195

Le roi Njoya: créateur de civilisation et précurseur de la renaissance africaine by L'Harmattan pg 254

Njoya’s Alphabet by Kenneth J. Orosz pg 48

African Crossroads: Intersections Between History and Anthropology in Cameroon by Ian Fowler pg 146-147)

Le roi Njoya: créateur de civilisation et précurseur de la renaissance africaine by L'Harmattan pg 257

Njoya’s Alphabet by Kenneth J. Orosz pg 49)

Le roi Njoya: créateur de civilisation et précurseur de la renaissance africaine by L'Harmattan pg 258

World Art and the Legacies of Colonial Violence by DanielJ. Rycroft pg 33-34

Le roi Njoya: créateur de civilisation et précurseur de la renaissance africaine by L'Harmattan pg 256

Écriture et texte: contribution africaine by Simon Battestini pg 356)

African Crossroads: Intersections Between History and Anthropology in Cameroon by Ian Fowler pg 157-163

La cartographie du roi Njoya by Alexandra Galitzine-Loumpet

Le Royaume Bamum by Claude Tardits 36-52 ).

Les dessins bamum: Marseille-Foumban (Cameroun) pg 48, 68

L'écriture des Bamum by Idelette Dugast, Mervyn David Waldegrave Jeffreys pg 29-30

World Art and the Legacies of Colonial Violence by DanielJ. Rycroft pg 38

Njoya’s Alphabet by Kenneth J. Orosz pg 55-59)

World Art and the Legacies of Colonial Violence by DanielJ. Rycroft pg 40-41

Njoya’s Alphabet by Kenneth J. Orosz pg 55