The kingdom of Dahomey and the Atlantic world: a misunderstood legacy

On the mythical "Black Sparta" of Africa.

There's no doubt that the Kingdom of Dahomey has the worst reputation among the African kingdoms of the Atlantic world, "the black Sparta" as it was conveniently called by European writers was an archetypal slave society, and like the ancient Greek city-state of Sparta which was known for its predominantly slave population1, human sacrifice2 and its famed military ethos; Dahomey was said to have been a highly militarized state that lived by slave trade and relished in its human sacrifices; it was described by some as a pariah state dedicated to the capture and sale of people to European slavers, by others as a state so addicted to violence that sale of its victims was an act of mercy, and by the rest as a state involuntarily attracted to the wealth of trade as well as the fear of becoming a victim of it.3 In all contemporary accounts of Dahomey's society, which were written solely by European traders and travelers, the central theme is slave trade, military and ritual violence, and the kingdom’s struggle to adjust to the end of slave trade.

The challenge with accurately reconstructing Dahomey's past became immediately apparent to modern historians, the bulk of written accounts about it prior to the early 20th century came from external observers, the vast majority of whom were actively involved in the slave trade in the 18th century, or were involved in suppressing the trade in the 19th century. And as historians soon discovered, the problem with these accounts is that European observers often assumed that their central concerns in visiting the kingdom, such as slave trade and its abolition, as well as the development of "legitimate commerce", were equally the central concerns of the monarchy; but this was often not the case, as traditional Dahomean accounts of its history seemed more concerned with its independence from its overlords such as Oyo and Allada, as well as the expansion of the kingdom, the consolidation of new territory and its religious customs.4 This was in stark contrast to what the European writers were pre-occupied with, especially the British, whose primary concern at the time was the heated debate about slave abolition between pro-slavery camps and abolitionist camps.

British writers such as William Snelgrav (1734), Robert Norris (1789), and Archibald Dalzel (1793) who belonged to the pro-slavery camp and were concerned with defending the trade, argued that Dahomey was essentially an absolutist and militaristic state, describing its “despotic” monarch who presided over “unparalled human sacrifice” to an extent that made the export of slaves a humane alternative. On the opposite side were writers such as John Atkins (1735) and Frederick Forbes (1851) who were abolitionists and were primarily concerned with proving the negative impact that slave trade had on African societies, they thus argued that it was because of slave demand and the subsequent capture of slaves, that Dahomey's militarism and the autocracy of its kings arose, along with its sacrifices.5

Neither of these camps were therefore concerned with providing an accurate reconstruction of Dahomey's past but were instead pre-occupied with making commentary on Dahomean culture to prove their polemic points in relation to the slave abolition debate, its thus unsurprising that Dahomean elites' response to the debates about the abolition and the European conception of Dahomey was one of astonishment at the brazen mischaracterization; when the king kpengla (r. 1774-89) was informed of the debates about abolition and Dahomey's centrality in them, he replied that Dahomey was in the middle of a continent and was surrounded by other people, and that it was “obliged, by the sharpness of our swords, to defend ourselves from their incursions, and to punish the depredations they make on us . . . your countrymen, therefore, who allege that we go to war for the purpose of supplying your ships with slaves, are grossly mistaken".6

This article provides an overview of the history of Dahomey focusing on the misconceptions about its Militaristic nature, its role in the Trans Atlantic slave trade, its religious practices as well as its transition from slave trade to legitimate commerce.

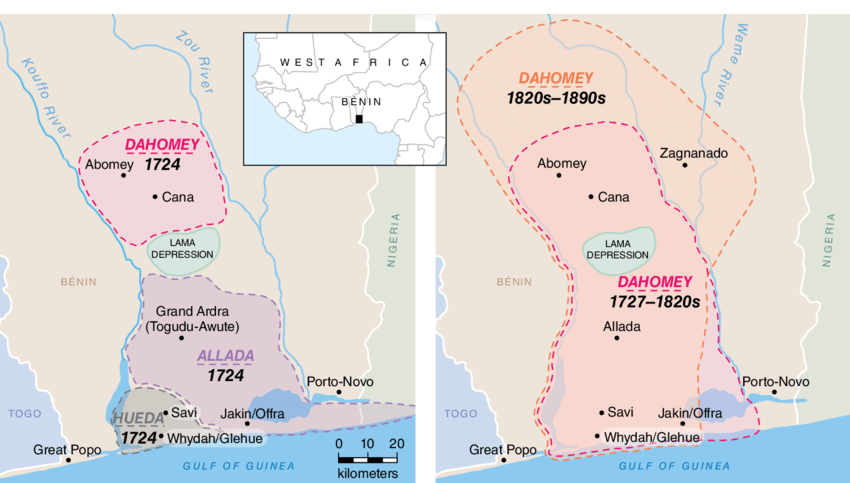

Map showing Dahomey and its neighbors in the Bight of Benin during the late 18th century

Support AfricanHistoryExtra by becoming a member of our Patreon community, subscribe here to read more about African history, download free books, and keep this newsletter free for all:

Dahomey’s origins ; from the emergence of complex societies in the Abomey plateau to the rise of the kingdoms of Allada and Hueda

The Abomey plateau in southern Benin, which was the heartland of Dahomey kingdom, had been settled since the mid 1st millennium by a series of small shifting societies with increasing social complexity. These incipient states were characterized by household production with crafts manufactures including iron smelting, pottery and textile production. They were engaged in long distance trade with the interior and the coast, that was carried out at large markets held every four days where the biggest trade item was most likely iron whose production in the southern Benin region had increased from 5 tones a year in 1400 to 20 tones a year in 1600 making it one of the largest production centers at the time in west Africa.7

The first of the large polities to emerge in the region was the kingdom of Allada in the 16th century with its capital, Grand Ardra housing more than 30,000 people, it exported ivory, cloth, slaves, palm oil, into the Atlantic world, it had a beauractraic system that administered the kingdom under the king with several offices such as a grand captain (prime minister), religious chiefs and a "captain of the whites"; the latter of whom was in charge of trade with the Europeans at its port city of Offra.

Allada’s social and political life included an elaborate annual custom that legitimated royal power and venerated deceased kings and was an occasion where luxury goods were distributed by the King among the state’s title-holders. By the late 17th century, slaves constituted the significant portion of Allada's exports but the King's share of the trade fell from 50% to less than 17% by volume, as private traders (both local and regional) provided the rest of the 83% among the approximately 8,000 slaves who left the region each year.

These private traders may have procured their slaves from the wars that characterized the emergence of Dahomey (which was previously subordinate to Allada), or more likely, these private traders were caravans from the larger kingdom of Oyo which had a well established slave trading system tapping into sources from further inland such as Borgu and Nupe, and which, after Dahomey's rise, seems to have redirected its trade from the Ouidah port to its own ports.8

By the late 17th century, Allada was in decline, and the kingdom of Hueda would emerge as a significant rival, attracting the construction of a number of European "forts", but also possessing a large local market with an attendance of over 5,000 people where a variety of local manufactures, commodities and food was sold for domestic consumption9.

On the Atlantic side of the economy, the export of slaves rose despite the decline of Allada, likely because the Hueda kingdom incentivized the slave caravans coming from long distance routes into the interior states like Oyo and Borgu mostly by reducing taxes paid on each slave to a low of 2.5% of the selling price, rather than through warfare since Hueda was a small polity demographically and geographically, with an equally weak army despite its possession of firearms.

More than 15,000 enslaved people embarked from its port at Ouida annually in the early 18th century making up the bulk of the 20,000 slaves sold in the entire “Bight of Benin” region, this figure was attained after Hueda redirected the trade from the port of Offra which had rebelled against Allada.10

coronation of the King of Hueda in 1725 by Jacob van der Schley

Dahomey was in origin an offshoot of Allada, founded by a prince of the royal house of that kingdom in the interior to the north, and adopted many of Allada’s customs. In the early 18th century, Dahomey emerged as the most powerful kingdom in the area, and invaded and conquered both Allada and Whydah in the 1720s under the reign of King Agaja (r. 1718-1740).

The formative period of state formation in Dahomey, like in the any other state, was a drawn out process, neighbors were conquered, political rivals silenced, and subjects integrated into a new political system, an administrative structure was set up centered at Abomey, which became the kingdom’s capital, as well as at Cana the royal residence, and at Ouidah its “port” city, in the latter, it was headed by the Yovogan (captain of the whites) and a viceroy who was later assisted by other officials and several private merchants. The town of Ouidah housed about 10,000 people, while Abomey had 24,000 people and Cana had 15,000 people in the 18th century11.

Dahomey emerges in the 18th century as a centralized state with a complex bureaucratic apparatus, neither an autocratic bureaucracy nor geared solely toward the Atlantic commerce but incorporating a range of administrative practices and policies that extracted wealth from the kingdom's rural and agricultural activities as well as tribute from subordinate polities and booty from conquests.12 the conquest of the coastal kingdoms was a long process that lasted well into the mid 18th century13

Map of southern Benin in the 18th and 19th centuries

Dahomey’s slave trade and militarism

After Dahomey’s conquest of the coast, slave trade at Ouidah immediately fell from 15,000 slaves in the 1720s to less than 9,000 in the 1750s, further to 5,000 in the 1760s and even further to 4,000 in the 1780s; representing a greater than 70% drop in slave exports despite the general rise in slave exports in the Bight of Benin region which at the time was exporting well over 14,000 slaves a year, and in an era when slave prices were rising.14

The king (or rather, the royal court) only supplied about 1/3 of the slaves of the 4,000 annual figure, this was after an attempt to monopolise the trade from private merchants during king Kpengla’s reign had failed, these private merchants supplied the majority of the slaves sold in Ouidah and it was the effects of the Dahomean policies on these private merchants which explain why slave exports fell after the conquest of the coast, one of these policies was the increase of taxes to 6.5% on each slave sold, from the previous low of 2.5%15

But even this wasn't the only factor because in 1787, the same King Kpengla mentioned that slaves "in the bush" (ie the price at which he bough them from the northern traders) cost less than 10% below the price which the Europeans were purchasing them, leaving Dahomey’s court with an extremely narrow profit margin, and he therefore tried to force the northern traders to sell to him at a lower price but they instead diverted their business from Dahomey’s port of Ouidah to the slave ports of Oyo whose exports now rose from nearly zero to over 10,000 annually16 such as Porto Novo, Badagry and even further to the port of Lagos in the Ijebu kingdom which emerged as the busiest port at the time. “Dahomeans’ lack of commercial and other acumen …and its conquests, disrupted a sophisticated trading network”17 or to put it simply, Dahomey was bad at business and bad for business.

While the decline of slave volumes from private merchants could have been offset by slaves procured from warfare, this alternative wasn't possible because Dahomey itself had a rather unsuccessful army despite its exaggerated reputation as a militarized “Black Sparta”.

The notion that Dahomey was a beleaguered state required to make constant war inorder to survive is a regular theme in Dahomean discussion especially in the correspondence between its kings ad the Europeans; including those involved in debates about slavery abolition such as the English as well as those unconcerned with abolition such as the Portuguese, and Dahomean leaders usually saw their wars as meeting primarily strategic and defensive aims in which the capture of slaves was secondary, this was not only made explicit in King Agonglo’s statement “in the name of my ancestors and myself I aver, that no Dahoman man ever embarked in war merely for the sake of procuring wherewithal to purchase your commodities.” but also in letters written by many Dahomean kings to the Portuguese describing several defensive wars where slavery was never the reason for waging war but appears as an afterthought. That slave capture was marginal to Dahomey’s wars is rendered even more tenable by the fact that Dahomey won only a third of the wars it was involved in.18

Dahomey’s relative military weakness compared to its peers such as Oyo and Asante is also unsurprising since Dahomey lay within a vulnerable region (militarily speaking) called the “Benin gap”, where savannah cut through the forest region down to the coast, allowing the northern cavalry armies such as Oyo’s to invade south but not allowing Dahomey itself to raise horses to defend itself because of it occupied a tsetse fly infested region, worse still was its vulnerability to coastal raiders such as the deposed Hueda kingdom that attacked (and attimes raided) the kingdom’s southern flanks routinely into the late 18th century. the supposed military ethos of Dahomey is more likely a consequence of this vulnerability rather than an inherent cultural trait; as one historian observes "It is not surprising that Dahomey’s rulers lived so much by war, for they were almost incapable of winning any war decisively, and were constantly vulnerable"19, and it was for this same reason that Dahomey was a tributary state of Oyo for much of the 18th century, subject to attacks which often ended in Dahomey’s defeat20 and an annual payment of a humiliating tribute.

It wasn't until Oyo's collapse in the early 19th century that Dahomey was able to decisively defeat its former suzerain in the 1820s, during this time, large groups of Yoruba speakers fleeing the disintegration of Oyo occupied Dahomey's eastern flanks establishing large settlements such as Abeokuta in its south-east which became the focus of a number of failed invasions from Dahomey in 1851 and 1864 proving yet again Dahomey's relative military weakness.21 as historian Edna Bay concludes "Dahomey was neither a military state nor a state with warring as its raison d’ ê tre. A military spirit was part of a larger pattern of ritual and political strategies to promote the well-being of the state"22 Given its status as a tributary state from the mid 18th to the early 19th century, it even harder to argue for the case of a full dominant and autonomous Dahomey state prior to the 1820s.

Dahomey religion and the question of human sacrifice

As with most religions, the principle of sacrifice was central to Dahomey’s religious beliefs, and while various animal sacrifices offered by the majority of the Dahomey society, human sacrifice was considered an extraordinary offering and was virtually restricted to the rulers.

The nature of human sacrifice in Dahomey as well as in some west African societies, was related to their religious beliefs in which the dead were commonly believed to exercise an influence over the world of the living, and humans were offered, among other sacrifices, inorder to secure the favor of supernatural beings that included both ancestors and deities (both of whom were considered interchangeable), added to this was the deliberate effect of sticking terror into those armies it had conquered, for example, the "Oyo customs" that started in King Gezo’s reign after Dahomey’s defeat of Oyo took place at Cana after the annual season of war, they commemorated the freeing of Dahomey from the suzerainty of Oyo that happened in the 1820s, and involved the ceremonial reenactment of the humiliating tribute Dahomey was forced to pay to Oyo, only this time the tribute carriers were 4 Yoruba captives from Oyo, after which they were ritualistically killed.23

The practice of human sacrifice was tied directly to the Dahomey’s ancestor veneration, Dahomey's religion recognized thousands of vodun, majority of which were said to link people to their deified ancestors, these vodun occupied the land of the dead (kutome) in a kingdom that mirrored the visible world of the living where the same royal dynasty reigned in both worlds and people enjoyed the same status and wealth in Kutome as in the visible world. The living King had power to influence the position of a person in the visible kingdom as well as in the Kutome and a living person who elevated their status had the power to elevate their status in the Kutome as well, and communication between the two worlds was mediated by diviners.24

The bulk of the sacrificial victims were often criminals of capital offences and their sacrifice was essentially an execution postponed to a singular date along with others25, these were also supplemented by war captives, as one observer in 19th century Dahomey noted: "what were commonly taken as human sacrifices 'are, in fact, the yearly execution, as if all the murderers in Britain were kept for hanging on a certain day in London".

The issue with contextualizing human sacrifice in west African history is interpreting the contemporary European accounts from which we derive most of our information on the practice, as the historian Robin law writes: "European observers undoubtedly, through ignorance or malice, often interpreted as human sacrifices killings which were really of a different character for example, judicial executions, witchcraft ordeals, or even political terrors, European sources therefore unquestionably give a greatly exaggerated impression of the incidence of human sacrifice in West Africa, and have to be used with the greatest caution".26

We therefore have no reliable estimates of how many were sacrificed at the annual customs, in the 18th century, the total annual customs are said to have involved between 100 to 200 victims, peaking at 300 in the early 19th century before falling to 32 in the mid to late 19th century.27 But these figures are at best guestimates that rose and fell depending on how each Dahomean ruler was perceived to be conceding to British demands of ending the tradition, the true figures rose and fell depending on the military successes achieved in war.28

The exclusiveness of the tradition of human sacrifice to the royals was linked to legitimating the ideology of royal power, perhaps more importantly for the funeral sacrifice when the King died, the vast majority of the sacrificial victims; all of whom participated in the custom voluntarily, were closest associates of the deceased king who wielded the most influence in his government, these included some of his relatives, wives, guards and powerful officials.

Paradoxically, to exempt these high officials from the death requirement gave them life but also reduced their status within the political system of the succeeding king underscoring the prestige attached with the act of dying with the king, the sacrifices were also politically convenient as the officials knew their fate even before taking office, thus proving their loyalty to the King knowing that they will have to die with him.29

Dahomey and the so-called "crisis of adaptation": the era of Legitimate commerce

The ending of the slave trade and the replacement of slave exports with "legitimate trade" commodities exports such as palm oil, gum Arabic and groundnuts has generated a wealth of theories about its effects on the political and economic structures of the Atlantic African states, this era initially studied by pioneering researchers who described it as “a crisis of adaptation” in which coastal African states such as Dahomey were thought to have struggled to transition from the royal monopoly of slave exports to the less centralized agricultural exports like palm oil.

Recent studies of the era have however have challenged if not wholly discredited this theory of “crisis”, showing that Atlantic states transitioned into the era of legitimate commerce without significant economic or political repercussions, for Dahomey in particular the historian Elisée Soumonni concludes that “the transition from slaves to palm oil was a relatively smooth process, and the 'crisis of adaptation' was successfully surmounted”30

That states such as Dahomey were able to "transition" successfully into legitimate commerce was doubtlessly enabled by the rise in palm oil prices throughout the mid 19th century but also the apparent marginality of slave trade to the economies of the region.

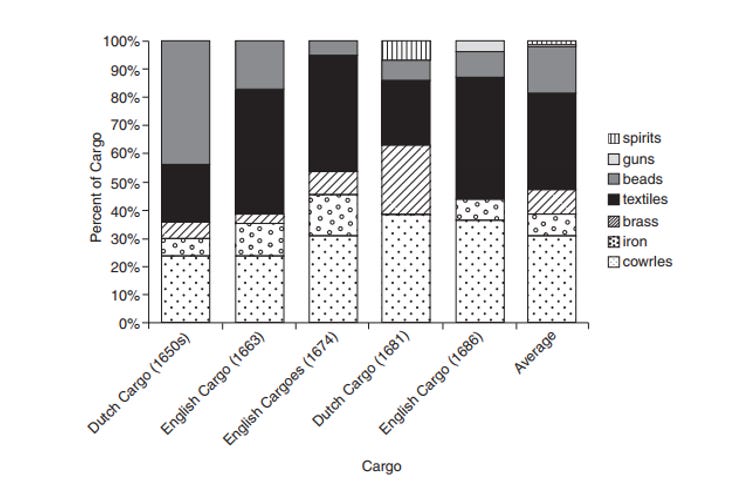

In his sweeping study of the African Atlantic economy, the historian John Thornton shows that African states imported items that were non-essential to their economies with the vast majority being produced (or could be procured) locally, such as textiles, glass-beads and iron as well as cowrie shells which had for long trickled in from the north through the Sahel, the majority of the items could not meet domestic African demand especially iron and textiles which at best contributed less than 2-10% of the domestic demand, he therefore concludes that the African side of the Atlantic trade "was largely moved by prestige, fancy, changing taste, and a desire for variety" and the imports were far from disruptive as its often assumed31

estimates of cargo sold in the bight of Benin in the late 17th century showing the importance of glass beads, textiles, cowries and iron all of which were also acquired locally32

Recent studies of pre-colonial Africa's textile trade also reveal that rather than being displaced by European imports, textile production expanded concurrently with them, well into the 20th century and that regions which were large importers of cloth (including the bight of Benin) were also large exporters of cloth33, and Dahomey traditions also reveal that imported textiles and other goods weren’t primarily serving local markets but instead served a symbolic purpose; they "provided a means by which the monarchy and powerful persons in the kingdom solidified their patronage".34

procession of the King’s wealth, Abomey, 1851 (illustration by Frederick Forbes)

While the demographic impact of slave trade on Dahomey itself hasn't been studied, the estimates in the region of west-central Africa (where half of all slaves were procured) reveal that the dispersed nature of procuring slaves (through private merchants along long distance routes) meant that there wasn’t a depopulation of the region but quite the opposite, there was instead a natural population growth that continued uninterrupted from the 16th to the 19th century in Kongo35

Some historians of Dahomey have also challenged the theory that slave trade depopulated the region by pointing out that older theories ignored the slave supply of interior kingdoms in Dahomey's north east such as Oyo and Borgu which constituted the bulk of private supplies offsetting the need for procuring them nearby, contending that even in the case of more localized enslavement, such as after Dahomey’s wars with Mahi kingdom, "the effects of the loss of a fair percentage of the male population may not necessarily affect radically the rate of natural increase".36 It should be noted that Dahomey had strict laws against enslaving its own citizens and protecting them from enslavement was a constant pre-occupation of the Dahomey rulers.37

(read this for more on the effects of the Atlantic slave trade)

The political effects of the Abolition of slave trade: the figure of Francisco de Souza

The historiography of the transition to legitimate commerce used to be preoccupied with the correspondence between the Dahomey Kings Gezo (r. 1818-1858) and Glele (r. 1858-1889) and the Europeans especially the British who were concerned with ending the slave trade and to a lesser extent, human sacrifice, both of which Gezo seems to have reduced.

But the policies of Gezo were complicated and unlikely to have been dictated nor even influenced by British demands, for example his predecessor Adandozan (r. 1797-1818) whom he deposed is according to tradition said to have reduced the export of slaves and the number of human sacrifices which Gezo is claimed to have reversed. Gezo also initially actively pursued alternative buyers of slaves after the British ban but later reduced these exports, and the fact that Gezo's coup was supported by the Brazilian slave trader Francisco Felix de Souza is often used to point to an influence of the Atlantic trade, but such violent successions were the norm rather than the exception in Dahomey’s history; with palace skirmishes often following the death of each king.38

Francisco Félix de Sousa

The position of De Souza in Dahomey’s politics has been greatly exaggerated by later historians based on an uncritical reading of contemporary accounts written by european travelers who at times dealt with him directly in correspondence rather than the king, not only was De Souza not an important figure in Dahomey politics, but he was also not a singularly powerful figure in the town of Ouidah itself where he lived, with the Yovogan Dagba remaining the paramount local authority.

The Yovogan Dagba belonged to an aristocratic family in Abomey and served the office for 50 years at Ouida in reward for his support of Gezo's coup and is unlikely to have had his power overshadowed. De Souza's position was also largely commercial rather than political, but even in this field he was not the greatest among his peers because there were several private merchants flourishing at the same time he was active in Ouidah such as the Adjovi and Houenou families who were much older and had even stronger ties to the Abomey court than De Souza.

The irony in De Souza's supposed influence on Gezo is that the trader spent his later life as a pauper and was deeply in debt to Gezo on his death to a tune of $80,000 (about $280,000 today), with his son having to borrow to pay for his funeral expenses!

It turns out that of all the traders active during the era of legitimate trade, it was De Souza who suffered the "crisis of adaptation"; while the rest were planting palm oil, De Souza’s slave ships were being seized by the British navy, his slaves freed and the rest of his wealth confiscated. The coup of Gezo and his reign “owed his success to the support, not of de Souza alone, but of the Ouidah merchant community” and the singular focus on De Souza is therefore a product of European exaggeration and later historian's accounts that, which, added to the family's prominence in the colonial era as well as recently as a tourist site, resulted in overstating the role of De Souza in Dahomey’s history.39

Brass ceremonial staff (Asen) from the mid 19th century depicting the Yovogan with his attendants (barbier mueller museum)

Conclusion : on Dahomey’s mischaracterization, retrospective guilt and Atlantic legacies

The reconstruction of Dahomey's history has been plagued by the general mischaracterization of the African past in which historians paint a European image of Africa that is decidedly more European than African, an image that is largely determined by and changed in accordance with European preconceptions, rather than African realities. The pre-occupation that European writers had with the African export goods such as slaves, ivory or gold was assumed to be central to African economies and politics but this was often not the case, historians in south east Africa for example have shown that gold and ivory exports were peripheral to the economies and political life of the regions' states40, so have historians in west Africa and west central Africa argued against the presumed centrality of slave exports to these regions economies, not just qualitatively in terms of the share of the trade to the domestic economy, but also qualitatively in terms of the effects its ban had on the politics of the legitimate trade.41

The pervasive eurocentric conception of African past has led to the creation of an arbitrary moral campus on which African rulers and states are measured based on their participation in the slave trade, with some kingdoms/rulers held up as opponents of slave trade while others are vilified as “bloodthirsty patrons of the slave trade”.42 This myopic exercise in moralizing history is a lazy attempt at retrospectively ascribing guilt for what was then a legal activity and a deflection from the the true crime of slave trade; which is its legacy, this is the point where African slave societies and American slave societies diverge, because while African slave societies assimilated former slaves into their societies, and the colonial and independent states that succeeded them were able to establish a relatively equal society for both its slave descendants and free descendants43, the American slave societies created robust systems of social discrimination which ensured that the decedents of slaves continued to occupy the lowest rungs of society, depriving them of any economic and social benefits that were realized by the descendants of free-born citizens once these states transitioned from slave society to free societies.44

While the debates about slavery, abolition and reparations are beyond the scope of this article, the eurocentric interpretation of Dahomey's history has dragged it into these discourses with themes of African "culpability" and African "agency" in which detractors point to Dahomey’s slave selling history as a counter to the accusations leveled against the European slave buyers and the settler states which they established with slave labor, but besides the deliberate misdirection of such debates, the basis of the arguments which they use against Dahomey are often pseudohistorical.

African states, were not defined by phenomena happening in Europe nor its colonies, their economies weren't dominated by European concerns and their political trajectory owed more to internal factors than coastal business. A faithful reconstruction of the African past should be sought outside the western-centric conceptual framework, or as one historian puts it crudely, it should be divorced from the "incestuous relationship between history and what is traditionally called Western Civilization" that binds Africanists into an apologetic tone and forces them to compare the subjects of study to the European ideal45. The religion, practices, customs of Dahomey don't subscribe to the fictional moral universalism defined by European terms but rather to the world view of the Fon people of Benin, and its these that created and shaped the history of their Kingdom.

In his observation of the modern Beninese wrestling with Dahomey's past, its legacy and its position in the republic of Benin, the writer Patrick Claffey concludes that "Dahomey is a narrative of Pride and suspicion, but it's equally a narrative of pain and division"46 its history remains as controversial and as exotic as it was in the 19th century polemics; "the Black Sparta" of Africa.

ruined entrance to the palace of Abomey, Artworks taken from the Palace (now at the Quai Branly museum in France)

Read more on Dahomey and the Slave trade in these books on my Patreon account

Slaves and Slavery in Ancient Greece By Sara Forsdyke

Human Sacrifice in Ancient Greece By Dennis D. Hughes

The Precolonial State in West Africa By J. Cameron Monroe pg 15-19

Wives of the leopard by Edna G. Bay 27-39

The pre-colonial state in west-africa by J. Cameron Monroe pg 15-16)

Abolitionism and Imperialism in Britain , Africa, and the Atlantic Derek R. Peterson pg 55

The pre-colonial state in west-africa by J. Cameron Monroe pg 36-42)

Slave Traders by Invitation by Finn Fuglestad pg 96-101)

Ouidah The Social History of a West African Slaving 'port' 1727-1892 by Robin Law pg 28-40

Ouidah The Social History of a West African Slaving 'port' 1727-1892 by Robin Law pg 46-49)

Ouidah The Social History of a West African Slaving 'port' 1727-1892 by Robin Law pg 73)

The pre-colonial state in west-africa by J. Cameron Monroe pg 73)

Ouidah The Social History of a West African Slaving 'port' 1727-1892 by Robin Law pg 59-70)

Ouidah The Social History of a West African Slaving 'port' 1727-1892 by Robin Law pg 123-124)

Ouidah The Social History of a West African Slaving 'port' 1727-1892 by Robin Law pg 112-118)

Ouidah The Social History of a West African Slaving 'port' 1727-1892 by Robin Law pg 145)

Slave Traders by Invitation by Finn Fuglestad pg 97

Africa's Development in Historical Perspective by Emmanuel Akyeampong et al. pg 444-458)

Warfare in Atlantic Africa, 1500-1800 by John Kelly Thornton pg 76)

Warfare in Atlantic Africa, 1500-1800 by John Kelly Thornton pg 75-79)

Wives of the Leopard by Edna G. Bay pg 185-186)

Wives of the Leopard by Edna G. Bay pg 130)

Wives of the Leopard by Edna G. Bay pg 215

Wives of the Leopard by Edna G. Bay 22-23),

Human Sacrifice in Pre-Colonial West Africa by R LAW pg 57-59)

Human Sacrifice in Pre-Colonial West Africa by R LAW pg pg 60)

Human Sacrifice in Pre-Colonial West Africa by R LAW pg 68-69)

Wives of the Leopard by Edna G. Bay pg 266-267, )

Wives of the Leopard by Edna G. Bay 162-164 269)

From Slave Trade to 'Legitimate' Commerce by Robin Law pg 1-20)

Africa and Africans in the Making of the Atlantic World by John Thornton pg 44-53)

The pre-colonial state in west-africa by J. Cameron Monroe pg 44

Twilight of an Industry in East Africa by Katharine Frederick

Wives of the Leopard by Edna G. Bay pg 123-126)

Demography and History in the Kingdom of Kongo, 1550–1750 by John Thornton

Slave Traders by Invitation by Finn Fuglestad pg 100)

Africa's Development in Historical Perspective by Emmanuel Akyeampong pg 455

Wives of the Leopard by Edna G. Bay pg 159-165)

Ouidah The Social History of a West African Slaving 'port' 1727-1892 by Robin Law `165-178)

see Port Cities and Intruders Michael N. Pearson and The Zimbabwe Culture by Innocent Pikirayi,

A History of West Central Africa to 1850 by John K. Thornton and From Slave Trade to 'Legitimate' Commerce by Robin Law, although the effects of slave trade on african economies is still subject to debate see Joseph E. Inikori, Paul E. Lovejoy and Nathan Nunn

Abolitionism and Imperialism in Britain, Africa, and the Atlantic by Derek R. Peterson pg 38-58)

for Dahomey’s case on the fate of slaves in colonial benin and independent republic, see “Conflicts in the domestic economy” in Slavery, Colonialism and Economic Growth in Dahomey by Patrick Manning

there’s plenty of literature on this but “Born in Blackness” by Howard W. French provides the best overview of American slave societies and their modern legacy.

Slave Traders by Invitation by Finn Fuglestad pg 54)

Christian Churches in Dahomey-Benin By Patrick Claffey pg 99-113

Although I was late to reading this article, I want to thank you for posting this article. What I have noticed on the internet time and time again is that there is often an agenda to try and portray every west-central African society that participated in some form or another in the Trans-Atlantic slave trade, as being dependent on the Trans-Atlantic slave trade economically to the point of their own destruction. Which is just not true, I mean, just look at all of the articles concerning Benin. The kingdom of Benin barely participated in the Trans-Atlantic slave trade yet most articles on Benin portray a kingdom that was dependent on the slave trade to it's own destruction. Hell, the claim that African kingdoms were completely depopulated because of the Trans-Atlantic slave trade is still pretty popular on the internet even though there is no proof to back that up. But not only do west-central African kingdoms like Kongo, Benin, Dahomey etc. get this treatment. But even the Sahelian kingdoms as well.

I have seen multiple articles try and convince me that the Trans-Saharan slave trade was the most crucial aspect of the empires of the Western Sudan (even though the main exports of Mali, Ghana and Songhai wasn't slaves). And the history of the Trans-Saharan and Indian ocean slave trades are both heavily exaggerated in order to make it parallel with the Trans-Atlantic slave trade(sometimes they are even claimed to be larger than the Atlantic slave trade, that is obviously a gateway to try and downplay the horrors of the Atlantic slave trade). It blatantly seems to me that people want to reduce Africa's history to slavery as much as they can, which I think is apart of how much colonial ideas still impact African historiography.

Anyways, very informative article.