The kingdom of Kongo and the Portuguese: diplomacy, trade, warfare and early Afro-European interactions (1483-1670)

On the history of a west-central African power in the early Atlantic world and the question of African agency.

The kingdom of Kongo is one of Africa's most recognizable pre-colonial states, but its history is often narrated with the theme of tragedy, from the virtuous and sympathetic king who was betrayed by his shrewd European "brother" that undermined his authority and rebuffed his complaints, to a kingdom torn apart by slavery caused by European interlopers, and to its war with the european musketeers; whose superior technology and military might ultimately ended its independence. The tragedy of Kongo in the 15th and 16th century was seen as the harbinger of what was to befall the African continent with the slave trade that peaked in the 18th century and colonialism of the late 19th century, the appealing theme of the story with its easily identifiable heroes (played by the Kingdom of Kongo) and villains (played by the kingdom of Portugal), is compounded by the colonial atrocities that were committed in the nation of Congo under Belgian rule, an equally tragic nation which inherited the Kingdom’s name.

But the complexities of early Afro-European interactions defy the simplicity of this theme of tragedy and the parallels drawn between the kingdom of Kongo and the colony of Congo are rendered facile on closer examination. The ability of Europeans to influence internal African political processes was very limited up until the late 19th century; whether through conquest or by undermining central authority, their physical presence in the interior of Kongo numbered no more than a few dozen who were mostly engaged in ecclesiastical activities, and their "superior technology and military might" never amounted to much after the first wave of colonialism in the 16th and 17th century ended with their defeat at the hands of the African armies of several states including Kongo. The evolving form of commerce and production in the early Atlantic world that resulted in nearly half the slaves of the Atlantic trade coming from west-central Africa (a region that included the kingdom of Kongo) was also as much about the insatiable demand for enslaved laborers in Portugal’s American and island colonies as it was about the ability of west-central African states like Kongo to supply it. While this slave trade may fit with some of the tragic themes mentioned earlier, especially given that the demand and incentives to participate in the slave trade outweighed the demographic or moral objections against it, it was nevertheless largely conducted and regulated under African law, and as such had a much less negative effect on the citizenry of the states conducting it than on the peripheries of those states where most of the slaves were acquired. Its because of this fact that Kongo was one of the few African states that effectively pulled out of the exportation of slaves to the Atlantic (along with Benin, Futa Toro and Sokoto) in an action that was enabled by Kongo’s capacity to produce and sale its textiles which were exchanged for the same products that had been acquired through slave trade. The slave trade had grown expensive after a while, and involved costly purchases from “middle men” states on Kongo’s peripheries after its military expansionism had ceased by the late 16th century.

The tragic themes used in narrating the history of Kongo undermine the dynamic reality of one of africa’s strongest, and most vibrant kingdoms, a truly cosmopolitan state that was deeply involved in the evolving global politics of the early Atlantic world, with a nearly permanent presence on the three continents of Africa, America and Europe. An African power in the early Atlantic world whose diplomats were active in the political and ecclesiastical circles of Europe in order to elevate its regional position in west-central Africa as well as complement its internationalist ambitions; its within this context that Kongo adopted a syncretistic version of christianity and visual iconography, masterfully blending Kongo's distinctive art styles with motifs that were borrowed selectively and cautiously from its Iberian partner. Kongo was a highly productive economic power with a flourishing crafts industry able to supply tradable goods such as cloth in quantities that rivaled even the most productive European regions of the day, it had a complex system of governance with an electoral council that checked the patrimonial power of the king and sustained the central authority even through times of crises, it had a relatively advanced literary culture with a school system that produced a large literate class, and a military whose strength resulted in one of Europe's worst defeats on the African continent before the more famous Ethiopian battle of Adwa.

This article offers a perspective of Kongo's history focused on its cosmopolitan nature, particularly its interactions with the Portuguese in the fields of diplomacy, trade and warfare that upends the popular misconceptions and reductive themes in which these interactions are often framed. Starting with an overview of the political, economic and social structures of the kingdom of Kongo, to the Portuguese activities in Kongo and Kongo’s activities in Europe; exploring how their economic partnership evolved over the years leading up to their military clashes in the 17th century. These three processes occurred nearly simultaneously but will be treated in stages where each process was the predominant form of interaction.

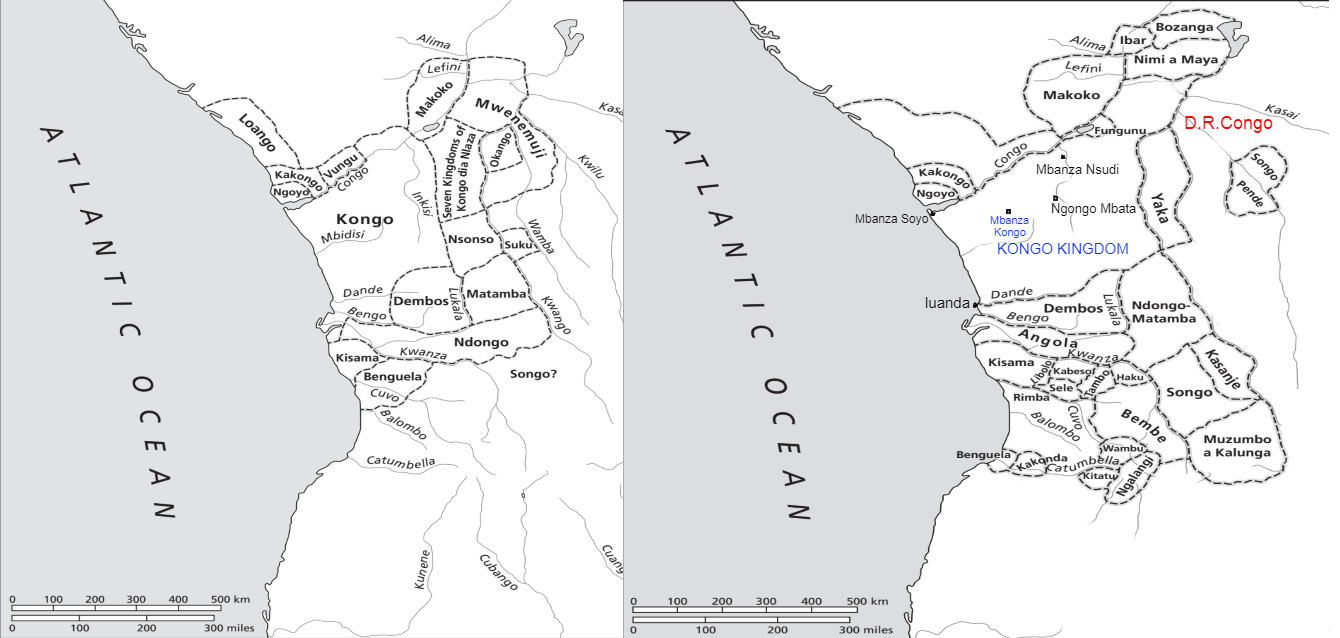

Map of the kingdom of Kongo and its neighbors in 1550 and 1650, showing the cities mentioned

Support AfricanHistoryExtra by becoming a member of our Patreon community, subscribe here to read more about African history, download free books, and keep this newsletter free for all:

Kongo’s Origins from Vungu to Mbanza Kongo: governance, cities and “concentrating” populations

The formation of Kongo begun with the consolidation of several autonomous polities that existed around the congo river in the 13th century such as Vungu, Mpemba and Kongo dia Nlaza, the rulers of Vungu gradually subsumed the territories of Mpemba and Kongo dia Nlaza through warfare and diplomacy, they then established themselves in Mpemba kasi (in what were the northern territories of Mbemba) and allied with the rulers of Mbata (in what was once part of Kongo dia Nlaza) and set themselves up at their new capital Mbanza Kongo around 1390AD as a fully centralized state: the kingdom of Kongo. Over the 15th and 16th centuries, Kongo would continue its expansion eastwards and southwards, completing the conquest of Kongo dia Nlaza (despite facing a setback of the jaga invasion of Kongo in the 1560s as well as losing its northern provinces to the emerging kingdom of loango), and extending its power southwards to the kingdoms of Ndongo, Matamba and the Dembos regions which all became its vassals albeit nominally.1

Kongo was at its height in the 16th century the largest state in west-central africa covering over 150,000 sqkm with several cities such as Mbanza Kongo, Mbanza Soyo, Mbanza Mbata and Mbanza Nsudi that had populations ranging from 70,000 to 30,000 and were characterized by "scattered" rather than “concentered” settlement containing ceremonial plazas, churches, markets, schools and palaces that occupied the center which was inturn surrounded by houses each having agricultural land such that the cities often extended several kilometers2, in Mbanza kongo, the city’s center was enclosed within a city wall built with stone and contained several brick churches, palaces and elite houses as well as houses for resident Portuguese. Kongo’s cities were the centers of the kingdom’s provinces, acting as nodes of political control and as tax collection hubs for the central authorities at Mbanza Kongo3. The king of Kongo (maniKongo) was elected by a council that initially constituted of a few top provincial nobles such as the subordinate rulers of the provinces of Mbata, Mbemba and Soyo, most of whom were often distantly related to the king but were barred from ascending to the throne4, these electoral councilors eventually grew to number at least twelve by the 17th century and the council's powers also included advising the king on warfare, appointment of government officials such as the provincial nobles, and lesser offices, as well as the opening and closing of trade routes in the provinces5. There were around 8 provinces in Kongo in 16th century and each was headed by officials appointed by the King for a three-year office term to administer their region, collect taxes and levees for the military. Taxes were paid in both cash (Nzimbu cowrie shells) and tribute (cloth, agricultural produce, copper, etc) in a way that enabled the maniKongo to exploit the diversity of the ecological zones in the kingdom, by collecting shell money and salt from the coastal provinces (the cowrie shells were “mined” from the islands near Luanda), agricultural produce from the central and northern regions, cloth from the eastern provinces and copper from the southern provinces; for which the kings at Mbanza kongo would give them presents such as luxury cloth produced in the east and other gifts that later came to include a few imported items6. Kongo's rise owed much to its formidable army and the successful implementation of the west-central African practice of “concentrating” populations near the capital inorder to offset the low population density of the region, Kongo achieved this feat with remarkable success since the kingdom itself had a population of a little over half a million in a region with no more than 5 people per sqkm, with nearly two fifths of the of these living in urban settlements7 and nearly 20% of the population (ie 100,000) living within the vicinity of Mbanza Kongo alone!8 dwarfing the rival capitals of the neighboring kingdoms of Loango and Ndongo that never exceeded 30,000 residents.

painting of Mbanza Kongo by Olfert Dapper in 1668. the central building was Afonso I’s palace, the round tower was still standing in the 19th century behind Alvaro’s cathedral of São Salvador on the right, the rest of the prominent buildings were churches whose crosses rose 10 meters above the skyline, interspaced with stone houses of the elite, all enclosed within a 6 meter high wall visible in the centre9

cathedral of Sao Salvador in Mbanza Kongo, Angola, rebuilt by maniKongo Alavro I and elevated to status of cathedral in 1596,10. It measures 31x15 meters, the bishops’ palace, servants quarters and enclosure wall -all of similar construction- measured about 250 meters11.

Christianity and Kongo's cosmopolitanism: literacy, architecture and diplomacy

When the Portuguese arrived on Kongo's coast in 1483, they encountered a highly centralized, wealthy and expansionist state that dominated a significant part of west-central Africa, but the earliest interaction between the two wasn't commercial or militaristic but religious, which was remarkably different with the other afro-portuguese encounters in the senegambia, the gold coast and Benin where both forms of interaction predominated early contacts and where religious exchanges were rather ephemeral. The early conversion of the Kongo royal court has for long been ascribed to the shrewdness of the reigning maniKongo Nzinga-a-Nkuwu (r. 1470-1509) in recognizing the increased leverage that Portuguese muskets would avail to him in fulfilling his expansionist ambitions or from the wealth acquired through the slave trade, but guns wouldn't be introduced in Kongo until around the 1510s12 and even then were limited in number and were decisive factor in war as often assumed, while slaves weren’t exported from Kongo until around 1512,13 added to this, the ephemeral conversions to christianity by several African rulers in the 16th century such as Oba Esigie of Benin, emperor Susenyos of Ethiopia, prince Yusuf Hassan of Mombasa city-state and the royals of the kingdom of Popo as well as some of Kongo’s neighbors, betrays the political intent behind their superficial flirtations with the religion.

Instead, the process of embracing christianity in Kongo took place in what the historian Cécile Fromont has called the “space of correlation” where Kongo’s and Portugal’s traditions intersected. Prior to this intersection, a few baKongo nobles had been taken to Lisbon in 1483 to teach them Portuguese and basic principles in catholism (a similar pattern had been carried out in most states the Portuguese contacted), these nobles returned in 1485 and after discussions with king Nzinga, he sent them back to Lisbon in 1487 (a year after similar diplomats from the west-African kingdom of Benin had arrived) returning to Kongo in 1490, and by 1491 they had converted Nzinga who took on the name Joâo I and also converted the mwene Soyo (ruler of Kongo's soyo province) as Manuel along with their courtiers, one of whom claimed to have discovered a cross carved in a black stone; which was a visual motif that coincidentally featured prominently in both Kongo cosmology and catholism and was recognised by both the baKongo and Portuguese audiences, thus legitimizing the King’s conversion by providing a common ground on which the baKongo and the Portuguese could anchor their dialogue.14 As historian John Thornton writes: "Miracles and revelations are the stuff that religious change is made of, although their role in confirming religious ideas is problematic to many modern scholars", the iconographic synthesis that resulted from this common ground underlined the syncretistic nature of Kongo's christianity which blended traditional beliefs and catholism and quickly spread under the direction of Joao I's successor Afonso I (r. 1509-1542) who took on the task of institutionalizing the church, employing the services of the baKongo converts as well as a few Portuguese to establish a large-scale education program, first by gathering over 400 children of nobles in a school he built at Mbanza Kongo, and after 4 years, those nobles were then sent to Kongo’s provinces to teach, such that in time, the laymen of Kongo's church were dominated by local baKongo. While his plans for creating a baKongo clergy were thwarted by the Portuguese who wanted to maintain some form of control over Kongo's ecclesiastical establishment no matter how small this control was practically since the clergy were restricted to performing sacraments.15 Nevertheless, the bulk of Kongo's church activity, school teaching and proselytizing was done by baKongo and this pattern would form the basis of Kongo and Portuguese cultural interactions.

Pre-christian crosses of Kongo’s cosmology depicted in rock paintings, textiles, and pottery engravings (Drawn by Cécile Fromont). they were also used by the traditionalist Kongo religion of Kimpasi which existed parallel to Kongo’s church and some of whose practitioners were powerful courtiers.

Christian art made by baKongo artists in Kongo; 17th century brass crucifix (met museum 1999.295.7), 19th century ivory carving of the virgin trampling a snake (liverpool museum 49.41.82), 17th century brass figure of saint Anthony (met museum 1999.295.1).

Kongo's architecture soon followed this synthesis pattern, the timber houses of Kongo's elite in the capital and in the provincial cities were rebuilt with fired bricks, stone and lime, and the original city wall of palisades was replaced by a stone wall 20ft high and 3ft thick that enclosed the center of the urban settlement in which stood several large churches, palaces of the kings, elite residences of the nobility, schools, markets and sections for the few dozen resident Portuguese and itinerant traders16. Kongo’s school system established by Afonso grew under his successors and led to the creation of a highly literate elite, with dozens of schools in Mbanza kongo and atleast 10 schools in Mbanza Soyo. Initially the books circulating in Kongo that were copied and written by local scribes were about christian literature17, but they soon included tax records and tribute payments (from the provincial rulers), language and grammar, law as well as history chronicles. Official correspondence in Kongo was carried out using letters, which now constitute the bulk of the surviving Kongo manuscripts because some of them were addressed to Portugal and the Vatican where dozens of them are currently kept, but the majority were addressed to provincial governors, the baKongo elite and the church elite, and they dealt with matters of internal politics, grants to churches, judgments, and instructions to itinerant Portuguese traders. Afonso I also established a courier system with runners that carried official letters between Mbanza Kongo and the provincial capitals, which greatly improved the speed of communications in the kingdom and increased its level of centralisation.18 Unfortunately, the manuscripts written in Kongo have received little attention and there has not been effort to locate Kongo’s private libraries despite the discovery of over a thousand documents in the neighboring dembos region some dating back to the 17th century19.

Ruins of a church at Ngonto Mbata in DRC and tombs in the cemetery of the Sao salvador cathedral. Ngongo Mbata was a town close to Mbanza Nsudi -a provincial capital in Kongo

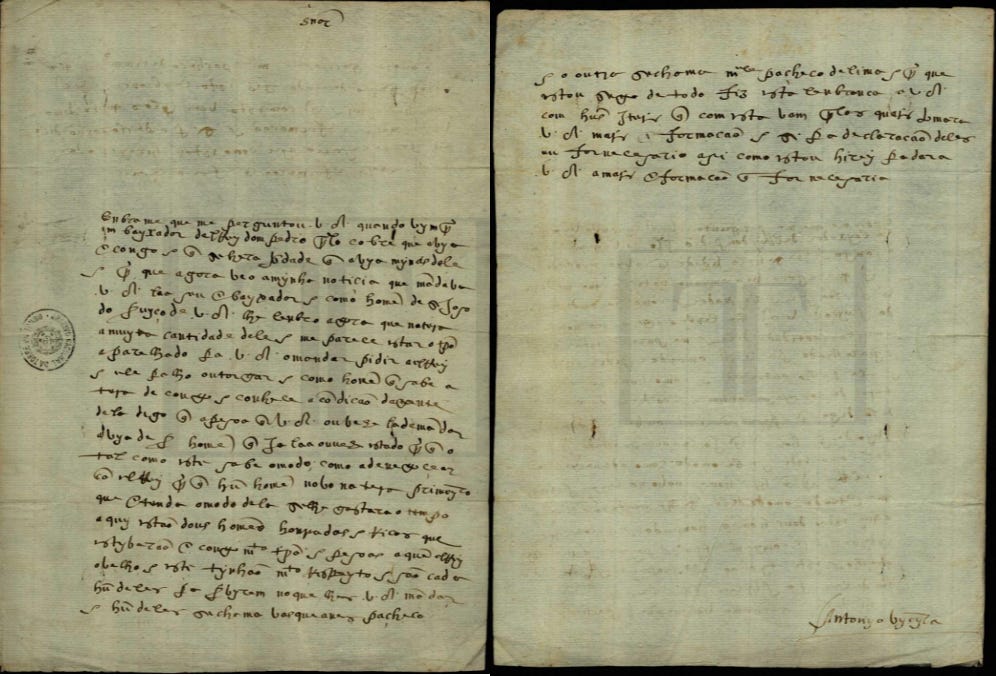

Letters from maniKongo Afonso I and Diogo, written in 1517, 1550 and addressed to portuguese monarchs (Arquivo Nacional Torre do Tombo, Portugal)

letter written by maniKongo Alvalro iii to Pope Paul V composed on 25th July 1617 (from the Kongo manuscript collection in the 'Vatican archives' under the shelf mark Vat.lat.12516, Mss № 70)20

The high level of literacy among Kongo's elite also enabled the creation of an ever-present class of diplomats from Kongo that were active in Europe and south America, the earliest embassy was the abovementioned 1487 embassy to Lisbon under King Joao I's reign and it was led by a muKongo ambassador Joao da silva, this was followed by another led by Pedro da sousa, a cousin of King Afonso I in 1512, and several others sent during his reign including one in 1535 that was sent to Rome. In the early decades of the 16th century these embassies were often accompanied by a number of students who went to lisbon to study before the travel was discontinued after Afonso I established schools in Kongo, but a sufficient presence of baKongo merchants was maintained in Lisbon and a sizeable community of baKongo grew in the portuguese capital and was placed under the maniKongo's factor resident in the city, the first of whom was António Vieira, noble man from Kongo that had arrived in Lisbon during the 1520s and was deeply involved in the affairs of the Portuguese crown eventually serving as the ambassador for maniKongo Pedro I (r. 1542-1545) and marrying into the royal family to Margaryda da silva, who was the lady-in-waiting of Queen Catharina of Portugal, the latter of whom he was politically close particulary concerning Kongo's trade relations with Portugal with regards to the discovery and trade of copper from Kongo’s provinces21. He was succeeded by another Kongo noble, Jacome de fonseca in this capacity, who served under maniKongo Diogo (r. 1545-1561), and during Alvaro II (r. 1587-1614) the office was occupied by another Antonio Vieira (unrelated to the first) who was sent to the Vatican in 1595, Alvaro II later sent another Kongo ambassador António Manuel in 160422. This tradition of sending embassies to various european capitals continued in the 17th century, to include Brazil (in the cities of Bahia and Recife) and Holland where several maniKongos sent diplomats, including Garcia II (r. 1641-1660) in 1643. Most were reciprocated by the host countries that sent ambassadors to Mbanza Kongo as well, and they primarily dealt with trade and military alliances but were mostly about Kongo’s church which the maniKongos were hoping to centralize under their authority and away from the portuguese crown, this was an endeavor that Afonso I had failed with his first embassy to the vatican, as the portuguese crown kept the Kongo church under their patronage by appointing the clergy but Alvaro II, working through his abovementioned ambassador Antonio Vieira, managed to get Pope Clement VIII to erect São Salvador (Mbanza kongo) as an episcopal See, this was after Alvaro I's deliberate (but mostly superficial) transformation of the kingdom to a fully Christian state by changing the nobilities titulature such as (dukes, counts and marquisates) as well as changing Mbanza Kongo’s name to São Salvador (named after the cathedral of the Holy Savior which he had rebuilt and whose ruins still stand )23 Kongo’s diplomatic missions strengthened its position in relation to its christian peers in Europe and were especially necessary to counter Portugal's influence in west-central Africa (and saw Portugal vainly trying to frustrate Kongo’s embassies to the Vatican). Kongo’s international alliances also strengthened its position also in relation to its peers in west-central Africa like Ndongo, its nominal vassal, whose embassies to Portugal were impeded by Kongo, the latter of whose informats told Ndogo’s rulers that portuguese missionaries whom their embassies had requested wanted to seize their lands, it was within this context of Kongo's attempt to monopolise and diplomacy between west-central African states (esp Ndongo) and portugal that Afonso I wrote his often repeated letter of complaint to the portuguese king João III claiming portuguese merchants were undermining his central authority by trading directly with his vassals (like Ndongo) and were “seizing sons of nobles and vassals”; but since there were only about 50 resident Portuguese in Kongo, all of whom were confined to Mbanza Kongo and their actions highly visible, and since Afonso I was granted the monopoly on all trade between west-central Africa and portugal24, this complaint is better read within the context of Kongo's expansionism where Ndongo remained a nominal vassal to Kongo for several decades and was expected to conduct its foreign correspondence and trade directly through Kongo25. As we shall later cover, the maniKongos had the power to recover any illegally enslaved baKongo even if they had been taken to far off plantations in Brazil.

Bust of António Manuel ne Vunda, 1629 at Santa Maria Maggiore Baptistery, Rome, Portrait of a Kongo Ambassadors to Recife (Brazil), ca. 1637-1644 by Albert Eeckhout at Jagiellonian Library, Poland. António is one of Kongo’s ambassadors mentioned above that was sent to Rome in 1609 by King Alvaro II, the ambassadors to Recife were sent during the period when Kongo allied with the Dutch

Letter written by Antonio Vieira written in 1566, addressed to Queen (regent) Catherine of Portugal and king Sebastian about the copper in Kongo ( Arquivo Nacional Torre do Tombo PT/TT/CART/876/130 )

Trade and industry in Kongo: cloth currency, copper, ivory and slaves.

Kongo's eastern conquests had added to the kingdom the rich cloth-producing regions that were part of west-central Africa's textile belt, in these regions, raffia was turned into threads that were delicately woven on ground looms and vertical looms to produce luxurious cloth with tight weaves, that were richly patterned, dyed and embroidered with imported silk threads26. Under Kongo, this cloth was manufactured in standard sizes, with unique patterns and high quality such that it served as a secondary currency called libongo that was used alongside the primary currenct of cowrie shells, and given cloth's utilitarian value, its importance in Kongo's architecture as wall hangings, its cultural value in burial shrouds (in which bodies were wrapped in textiles several meters thick), Kongo’s cloth quickly became a store of value and a marker of social standing with elites keeping hoards of cloth from across west-central Africa, as well as imported cloth from Benin kingdom and Indian cloth bought from portuguese traders. Libongo cloth was also paid to the soldiers in portugal’s colony of Angola because of its wide circulation and acceptance, the portuguese exchanged this cloth for ivory, copper and slaves in the other parts of the region where they were active, its from these portuguese purchases from Kongo that we know that upto 100,000 meters of cloth were imported annually into Luanda from Kongo's eastern provinces in 1611, which was only a fraction of the total production from the region and indicated a level of production that rivaled contemporaneous cloth producing centers in europe27. Another important trade item was ivory , while its hard to estimate the scale of this trade, it was significant and firmly under the royal control as King Garcia II had over 200 tusks (about 4 tonnes) in his palace in 1652 that were destined for export and were likely only fraction of Kongo’s annual trade28, copper was also traded in significant quantities although few figures were record, and between 1506 and 1511, Kongo exported more than 5,200 manilas of copper29 that weighed around 3 tonnes, most of which was initially destined for the Benin kingdom to make its famous brass plaques but much of it was later exported to Europe since the metal was in high demand in the manufacture of artillery.30

Kongo luxury cloth and a pillow cover inventoried in 1709, 1659 and 1737 at Museo delle Civiltà in rome, Ulmer Museum in Germany and Nationalmuseet in Copenhagen31

intricately carved side-blown ivory horn made in Kongo around 1553 as a diplomatic gift (Treasury of the Grand Dukes, italy). Close-ups on the right shows the typical Kongo patterning used on its textiles and pottery.

Slaves too, became one of Kongo's most important exports, the social category of slaves had existed in Kongo as in west central Africa prior to Portuguese contact as the wars Kongo waged in the process of consolidating the kingdom produced captives who were settled (concentrated) around the capitals and provincial cities in a position akin to serfs than plantation slaves since they farmed their own lands32 and some of them were integrated into families of free born baKongo. A slave market existed at Mbanza Kongo (alongside markets for other commodities) and it was from here that baKongo elites could purchase slaves for their households, the market likley expanded following the establishment of contacts with portugal and the latter's founding of the colony on the Sao tome and the cape verde islands whose plantations and high mortality created an insatiable demand for slaves.33 While figures from this early stage are disputed and difficult to pinpoint the exact origin of slaves, Kongo begun supplying Sao tome with slaves in significant quantities beginning around 1513 although Ndongo was already a big supplier by the end of that decade such that around 200 slaves arrived annually from west-central africa in the 1510s and by the 1520s, the figure rose to 1,000 a year34, some of the slaves were purchased in the Mbanza Kongo market and passed through its port at Mpinda and nearly all were derived from Kongo's eastern campaigns, but with growing demand, slave sources went deeper into foreign territory and Kongo had to purchased from its northeastern neighbors such as the kingdom of Makoko 35 . It was with the opening of this slave route that Kongo was able to export upto 5,000 in the 1550s before the trade collapsed, moving from Mpinda to Luanda, even then, Ndongo outsripped Kongo, exporting over 10,000 slaves a year 36. The slave trade in free-born baKongo was strictly prohibited for much of the 16th and 17th century as well as for most of the domestic slaves; and the maniKongos went to great lengths to ensure both group’s protection including going as far as ransoming back hundreds of enslaved baKongo from Brazil and Sao tome in two notable episodes, the first was during the reign of Alvaro I (r. 1568-1587), after the Jaga invasion of Kongo in which several baKongo were captured but later returned on Alvaro’s demands,37 and secondly, during the reign of the maniKongo Pedro II (r. 1622-1624) when over a thousand baKongo were returned to Kongo from Brazil as part of the demands made by Pedro following the portugal’s defeat by Kongo's army at Mbanda Kasi in 1623.38 Added to this was Kongo’s ban on both the export and local purchase of enslaved women39 which similar to Benin's initial ban on exporting enslaved women that soon became a blanket ban on all slave exports40. Because Kongo mostly purchased rather than captured its slaves in war after the mid 16th century, it was soon outstripped by neighbors such as Ndongo and Loango (the latter of which diverted its northeastern sources) and then by the Portuguese colony of Angola which was the main purchaser of slaves that were then exported from Luanda, its capital, such that few slaves came from Kongo itself in the late 16th and early 17th century and much of the kingdom’s external commerce was dominated by the lucrative cloth trade.41 but following the civil wars and decentralization that set in in the late 17th century, Kongo became an exporter of slaves albeit with reducing amounts as it was weakened by rival factions who fought to control the capital, and by the 18th century, a weaker Kongo was likely victim to the trade itself42, after the 17th century it was from the colony of Angola and Benguela rather than Kongo where most slaves were acquired, most of whom were purchased from various sources and totaled over 12,000 a year by the early 1600s, although only a fraction came from Kongo because long after the kingdom’s decline in the 1700s when its territory was carved up by dozens of smaller states, the slave trade exploded to over 35,000 a year.43

The Kongo-Portuguese wars of the 17th century and the Portuguese colony of Angola.

In the mid 16th century, an expansionist Portugal was intent on carving out colonies in Africa probably to replicate Spanish successes in Mesoamerica where virtually all the powerful kingdoms had been conquered and placed under the Spanish crown. Coincidentally, Kongo was under attack from the jaga, a group of rebels from its eastern borders who sacked Mbanza Kongo and forced the maniKongo Alvaro I to appeal for portugal's help, an offer which king Sebastião I of portugal took up, sending hundreds of musketeers to drive out the rebels in 1570 in exchange for a few years control over the cowrie shell “mines” near luanda44. Not long after this attack, Álvaro I was secure enough on his throne to reclaim control over Luanda and ended the extraction of shells by Portugal45 he also sent a force to take control of Ndongo, but the latter adventure failed and a portuguese soldier named Dias de Novais, who had been given a charter to found a colony in Ndongo used this opportunity to form a sizeable local force that conquered part of Ndongo which he claimed for the portuguese crown as the colony of Angola, Dias had used luanda as his base and it was initially done with Alvaro's permission but Dias’ more aggressive successors loosened Kongo's grip over the city by the late 16th century and saw some successes in the interior fighting wars with small bands in the Dembos region (see the 2nd map for these two states south of Kongo), even though an attack into the interior of Ndongo was met with a crushing defeat at the battle of lukala in 1590 after Ndongo had allied with Matamba (another former vassal of Kongo). The portuguese recouped this loss in 1619 by allying with the imbangala bandits, who sacked Ndogo and carried away slaves before queen Njinga reversed their gains in the later decades.46

Swords from the Kingdom of Kongo made between the 16th and 19th centuries, (British museum, Brooklyn museum, Ethnologisches Museum Berlin, Royal central Africa museum, Belgium)

After their sucesses in Ndongo in 1619, the governors of Angola then set their sights on Kongo beginning by invading Kongo's southern province province of Mbamba intent on marching on the capital and conquering the kingdom, the duke of Mbamba's army met them at Mbumbi in January 1622 but was outnumbered 1:10 by the massive Portuguese force of 30,000 infantry that was swelled by imbagala bandits who were ultimately victorious over Mbamba's 3,000-man force, but not long after this engagement, Kongo's royal army battled the portuguese at Mbanda Kasi with a force of 20,000 men under the command of maniKongo Pedro II who crushed the Portuguese army, sending the surviving remnants streaming back to Angola. The itinerant Portuguese traders in Mbanza Kongo were stripped of their property by the locals despite the king's orders against it, and the governor of Angola Correia de Sousa, was forced to flee from Luanda after protests, but he was captured and taken to Portugal where he died penniless in the notorious Limoeiro prison47. As mentioned earlier, thousands of baKongo citizens were brought back from brazil where they had been sent in chains after the defeat at Mbumbi.

After his victory at Mbanda Kasi, the maniKongo Pedro II allied with the Dutch; making plans to assault Luanda with the intention of rooting out the Portuguese from the region for good, but died unexpectedly in 1624 and his immediate successor didn’t follow through with this alliance as there were more pressing internal issues such as the increasing power of the province of Soyo48. Three maniKongos ascended to the throne in close succession without being elected; Ambrósio I (r. 1626-1631), Álvaro IV (r. 1631-1636) and Garcia II (1641-1660)49 and while their reigns were fairly stable, they made the political situation more fragile and undermined their own legitimacy in the provinces by relying on the forces of afew provinces to crown them rather than the council, these [provinces were often ruled by dukes who were closely related to the reigning King and this set a precedent where powerful provincial nobles marched onto the capital to install their own kings, and the political insecurity of the appointed offices made by the increasingly absolutist Kings led to increased taxation by the nobles across the kingdom that caused tax revolts and a general distrust of central authority50. This erosion of legitimacy weakened the state’s institutions and affected the royal army’s performance which was routinely beaten by some of its provinces such as Soyo and continued weakening it to such an extent that when portuguese based at Angola wrestled with Kongo over the state of Mbilwa ( a nominal vassal to Kongo) it ended in battle in 1655 that resulted in the defeat of Kongo's army led by King Antonio who was beheaded by Portugal's imbangala allies.51 The province of Soyo took advantage of this loss and the precedent set by the ascent of unelected kings to back atleast two of the 6 Kings who were crowned in Sao salvador within the 5 years following Kongo’s loss, this was until a King hostile to Soyo was crowned, the soon-to-be manikongo Rafael enlisted the aid of portuguese forces from Angola to defeat the Soyo puppet king Álvaro IX and install himself as king. The Portuguese army, hoping to capitalize on their newfound alliance, marched onto Soyo itself but were completely annihilated at the battle of kitombo in 18 October 1670, the few portuguese captives that weren't killed in battle were later slaughtered by the Soyo army after turning down the offer to remain in servitude in Soyo. This formally marked the end of portuguese incursions in the interior of kongo until the late 19th century.52

Conclusion: Kongo’s decline, its legacy and early afro-European interactions.

The Kingdom of Kongo was reunited in 1709 by King Pedro IV, but it gradually declined as its central authority was continuously eroded by centrifugal forces such that by the 19th century, Kongo was but one of several kingdoms in west central Africa and before its last King Manuel III was deposed in 1914, he was no more wealthy that a common merchant. The capital Sao Salvador wasn't completely abandoned but became a former shell of itself and never exceeded a few thousand residents although it retained its sacred past; with its ruined churches, palaces and walls reminding the baKongo of the kingdom's past glory "like the medieval romans, inhabitants of sao salvador lived amidst the ruins of a past splendor of whose history they were full conscious"53 its ruins now buried in the foundations of the modern city of Mbanza Kongo, save for Alvaro’s cathedral of Sao salvador, known locally as NkuluBimbi: “what remained of the ancestors…”

The trajectory of Kongo’s growth was mirrored by a number of the medieval African states that interacted with Europeans in the early Atlantic era; with an export trade firmly under the control of African states which initially comprised of a mix of commodity exports such as gold and ivory and later slaves; a process of cultural synthesis between African and European traditions that was dictated and regulated by the choices of African patrons; and full political autonomy on the side of African states that successfully defeated the first wave of colonization as Portugal was flushed out of the Kongo and Ndongo heartlands in the 17th century, at the same time it was forced out of the Mutapa and Rozvi interior in south-eastern Africa and the Swahili coast of east Africa, relegating them to small coastal possessions like Luanda and the island of Mozambique from which they would resume their second wave of colonization in the late 19th century.

The misconception about the “tragedy of Kongo” gives an outsized role to Portuguese actions in influencing Kongo’s politics that aren’t matched by the reality of Kongo’s history in which, despite their best efforts, Portuguese were only minimal players; failing to control its church, failing to monopolise its trade and failing to conquer it. The successes and challenges faced by Kongo were largely a product of internal processes within the Kingdom where interactions with Europeans were peripheral to its main concerns and the cultural synthesis between both worlds was dictated by Kongo. Ultimately, the legacy of Kongo was largely a product of the efforts of its people; a west-central African power in the Atlantic world.

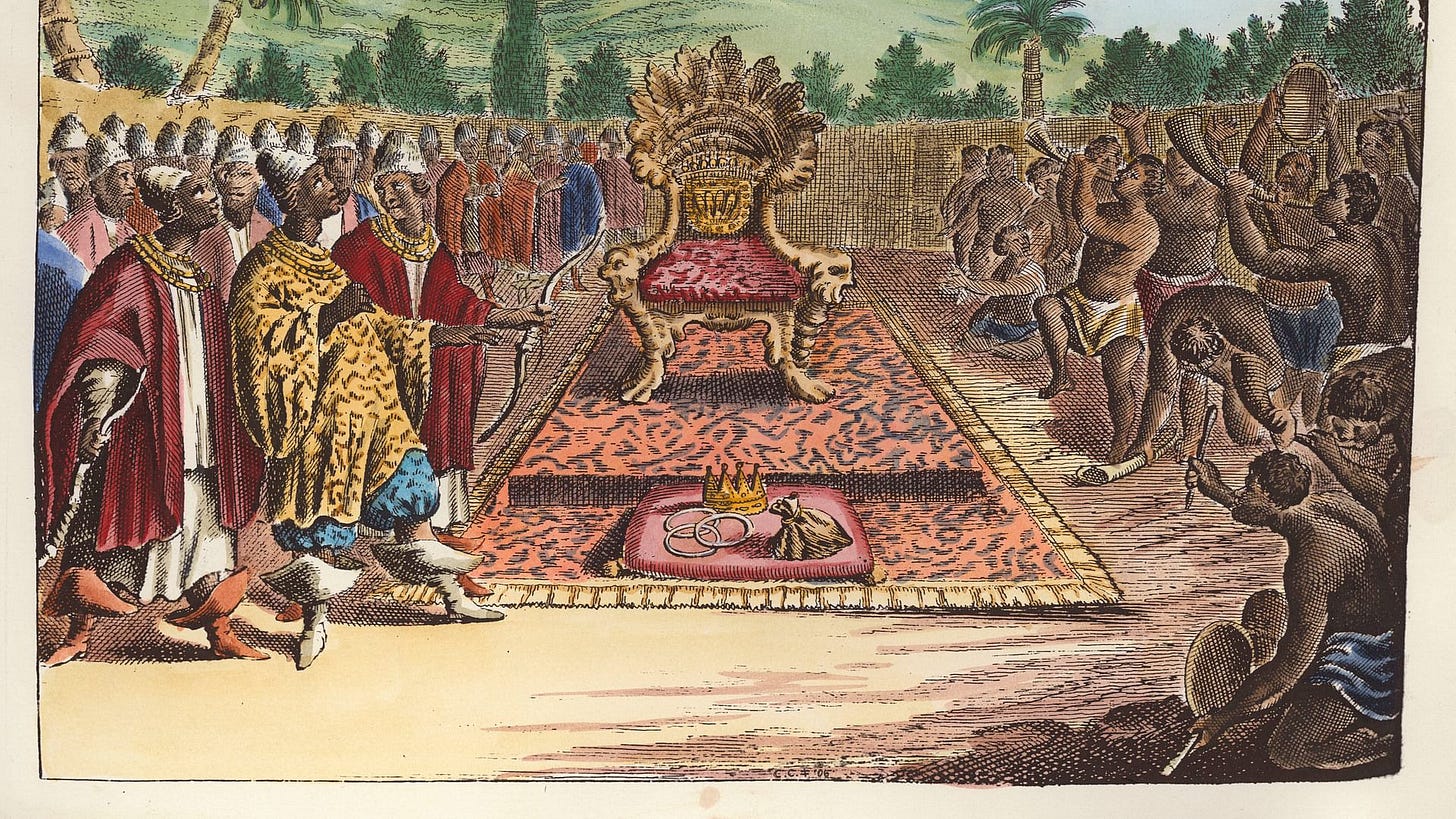

The throne of Kongo awaiting its King. (painting by olfert dapper, 1668)

for free downloads of books on Kongo’s history and more on African history , please subscribe to my Patreon account

The kongo kingdom by Koen Bostoen, Inge Brinkman, pg 36- 41.

the elusive archaeology of kongo’s urbanism by B Clist, pg 377-378

The elusive archeology of kongo urbanism by B Clist, pg 371-372

A History of West Central Africa to 1850 by J. K. Thornton, pg 34

The Kingdom of Kongo. by Anne Hilton, pg 38

The Kingdom of Kongo. by Anne Hilton, pg 34-35

Demography and history in the kingdom of Kongo by J.K.Thornton, pg 526-528

The Atlantic World and Virginia, 1550-1624 by Peter C. Mancall, pg 214

The Art of Conversion by C. Fromont pg 190-192, Africa's Urban Past By R. Rathbone, pg 70

Multi-analytical approach to the study of the European glass beads found in the tombs of Kulumbimbi (Mbanza Kongo, Angola) by M. Costa et al, pg 1

The Art of Conversion by C. fromont, pg 194-195

warfare in atlantic africa by J.K.Thornton, pg 108

the volume of early atlantic slave trade, pg 43

Under the sign of the cross in the kingdom of Kongo by C Fromont, pgs 111-113

Afro-christian syncretism in the Kingdom of Kongo by J.K.thornton, 53-65

Africa's urban past by David M. Anderson, pgs 67-70

The kongo kingdom by Koen Bostoen, Inge Brinkman, pg 218-224

The Kingdom of Kongo. by Anne Hilton, pg 79-84

Arquivos dos Dembos: Ndembu Archives

The Atlantic world and Virginia by Peter C. Mancall, pg 202-203

A History of West Central Africa to 1850 by J. K. Thornton, pg 108-109

A History of West Central Africa to 1850 by J. K. Thornton, pg 81

early-kongo Portuguese relations by J.K.Thornton, pg 190-197

A History of West Central Africa to 1850 by J. K. Thornton, pg 55

A history of west-central africa by J.K.Thornton, pg 12

pre-colonial African industry by J.K.Thornton, pg 12-13

A History of West Central Africa to 1850 by J. K. Thornton, pg 174

The Kingdom of Kongo. by Anne Hilton, pg 55

Red gold of africa by Eugenia W. Herbert pg 201, 140-141

Patterns without End: The Techniques and Designs of Kongo Textiles - met museum

A History of West Central Africa to 1850 by J. K. Thornton, pg 6-9, 72

the volume of early atlantic slave trade, pg 72

the volume of early atlantic slave trade, pg 72

The Kingdom of Kongo. by Anne Hilton, pg 57-59

Transformations in slavery by P.E.Lovejoy, pg 40

Slavery and its transformation in the kingdom of kongo by L.M.Heywood, pg 7

A reinterpretation of the kongo-potuguese war of 1622 according to new documentary evidence by J.K.Thornton, pg 241-243

Slavery and its transformation by L.M.Heywood, pg 7

A Critique of the Contributions of Old Benin Empire to the Trans-Atlantic Slave Trade by Ebiuwa Aisien, Felix O.U. Oriakhi

Africa and africans in making the atlantic world by J. K. thornton, pg 110-111

Slavery and transformation in the kingdom of Kongo by L.M.Heywood, pg 18-22

Transformations in slavery by paul lovejoy, pg 53-54, 74

A History of West Central Africa to 1850 by J. K. Thornton, pg 76-78

A History of West Central Africa to 1850 by J. K. Thornton, pg 82

A History of West Central Africa to 1850 by J. K. Thornton, pg 92, 118-20.

A History of West Central Africa to 1850 by J. K. Thornton, pg 128-132

The kongo kingdom by Koen Bostoen, Inge Brinkman, pg 115-116

A History of West Central Africa to 1850 by J. K. Thornton, pg 149-150, 160, 164

A History of West Central Africa to 1850 by J. K. Thornton, pg 176

A History of West Central Africa to 1850 by J. K. Thornton, pg 182

A History of West Central Africa to 1850 by J. K. Thornton, pg 185.

Africa's urban past by David M. Anderson, pg 73