The kingdom of Mutapa and the Portuguese: on the failure of conquistadors in Africa (1571-1695)

African military history and an ephemeral colonial project.

Among the most puzzling questions of world history is why most of Africa wasn’t overrun by colonial powers in the 16th and 17th century when large parts of the Americas and south-east Asia were falling under the influence of European empires. While a number of rather unsatisfactory answers have been offered, most of which posit the so-called “disease barrier” theory, an often overlooked reality is that European settler colonies were successfully established over fairly large parts of sub-equatorial Africa during this period.

In the 16th and 17th century, the kingdom of Mutapa in south-east Africa, which was once one of the largest exporters of gold in the Indian ocean world, fell under the influence of the Portuguese empire as its largest African colony. Mutapa’s political history between its conquest and the ultimate expulsion of the Portuguese, is instructive in solving the puzzle of why most of Africa retained its politically autonomy during the initial wave of colonialism.

This article explores the history of Mutapa kingdom through its encounters with the Portuguese, from the triumphant march of the conquistadors in 1571, to their defeat and expulsion in 1695.

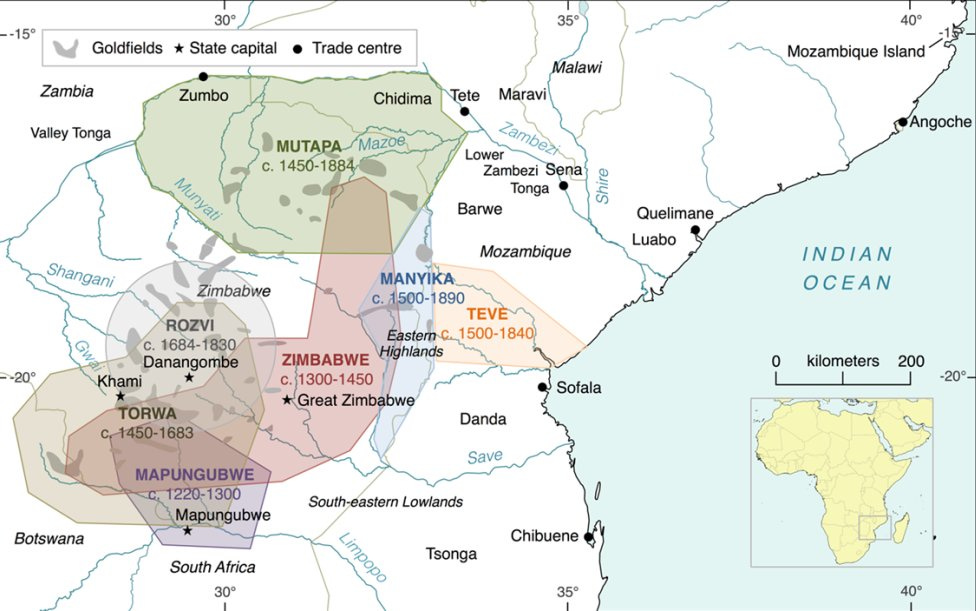

Map of the Mutapa kingdom (green) and neighboring states

Support AfricanHistoryExtra by becoming a member of our Patreon community, subscribe here to read more about African history, download free books, and keep this newsletter free for all:

Early Mutapa: Politics and Trade in the 16th century.

Beginning in the 10th century, the region of south-East Africa was dominated by several large territorial states that were primarily settled by shona speakers, whose ruler’s resided in large, elaborately built dry-stone capitals called zimbabwes the most famous of which is Great Zimbabwe. The northernmost attestation of this “zimbabwe culture” is associated with the Mutapa kingdom which was established in the mid 15th century by prince Mtotoa, after breaking away from Great Zimbabwe.1

Mtotoa’s successors were based in multiple capitals following shona traditions in which power rotated among the different lines of succession.2 They established paramountcy over territorial chiefs whose power was based on the control over subsistence agricultural produce, trade and religion. This paramountcy was exercised through the appointment of the territorial chiefs from important positions within the monarchy, and by a control over the coastal traders (Swahili, and later Portuguese), who were symbolically accommodated into the Mutapa political structure as the kings' wives.3

The economy of Mutapa was largely agro-pastoralist in nature, primarily concerned with the cultivation of local cereals and the herding of cattle, both of which formed the bulk of tribute. Long-distance trade and mining were mostly seasonal activities, the gold dust obtained through panning and digging shallow mines was traded at various markets and ultimately exported through the Swahili cities such as Sofala and Kilwa4. Other metals such as iron and copper were smelted and worked locally, alongside other crafts industries including textiles and soapstone carving, all of which occurred in dispersed rather than concentrated centers of production. Gold mining was nevertheless substantial enough as to produce the approximately 8.5 tonnes of gold a year which passed through Sofala in 1506.5

The Mutapa kings didn’t monopolise all trade activities in Mutapa's dominions, and long-distance trade was decentralized, the production and distribution of commodities destined for international markets in their dominions wasn't closely regulated but traders were nevertheless subject to certain taxes and tariffs. The main tax being the Kuruva which was originally paid by the Swahili traders in order to conduct trade in the state, and was later paid by the Portuguese after they took over the Swahili trading system.6

The ruins of Chisvingo in Zimbabwe, the southern half of the Mutapa kingdom. such zimbabwes served as the capitals of the Mutapa kings, this particular one is part of a cluster of ruins in Masembura that was dated to the 15th century7, with nearby ironworkings showing it continued to flourish until the 17th century.8

The first Portuguese invasion of Mutapa; from conquistadors to “King’s wives”

Beginning in the 1530s, a steady trickle of Portuguese traders begun settling in the interior trading towns and in 1560, an ambitious Jesuit priest travelled to the Mutapa capital to convert the ruler. His attempt to convert the king Mupunzagutu failed and the latter reportedly executed the priest, having received the advice of his Swahili courtiers about the Portuguese who'd by then already colonized most of the east African coast following their bombardment of Kilwa, Mombasa and Mozambique, the last of which was by then their base of operation.9

Long after the news about the priest's execution had spread to Portugal, a large expedition force was sent to conquer Mutapa ostensibly to avenge the execution, but mostly to seize its gold mines and its rumored stores of silver. An army of 1,000 Portuguese soldiers --five times larger than Pizarro's force that conquered the Inca empire-- landed in Sofala in 1571, it was armed with musketeers led by Francisco Barreto , and was supported by a cavalry unit. It advanced up to Sena but it was ground to a halt as it approached the forces of Maravi (Mutapa's neighbor), and while they defeated the Maravi in pitched battle, the latter fortified themselves, and the most that the Portuguese captured were a few cows.10

Another expedition was organized with 700 musketeers in 1573, supported by even more African auxiliaries and cavalry, and it managed to score a major victory in the kingdom of Manica but eventually retreated. A final expedition with 200 musketeers was sent up the Zambezi river but was massacred by an interior force (likely the Maravi). By 1576, the last remaining Portuguese soldier from this expedition had left.11

Following these failed incursions, the Portuguese set up small captaincies at the towns of Tete and Sena and formed alliances with their surrounding chieftaincies controlling the narrow length of territory along the banks of the Zambezi. Like the Swahili traders whom they had supplanted, the Portuguese traders were reduced to paying annual tax to Mutapa, and were turned into the 'king's wives'. 12

Deception and Mortgaging gold mines for power: rebellions in Mutapa

After surviving the Portuguese threat, the Mutapa king Gatsi had to contend with new challenges to his power, which included multiple rebellions led by his vassals. In 1589 a Mutapa vassal named Chunzo rebelled and attacked the gold-mines in the region of chironga and killed Gatsi's captain, but his rebellion was eventually crushed.13

During the course of this rebellion, a Mutapa general named Chicanda rebelled and invaded Gatsi's capital, but was later pardoned and permitted to stay as a vassal. He rebelled again in 1599 --ostensibly after Gatsi had one of his generals executed for not fighting Chunzo--, and this time Gatsi called on the Portuguese stationed at TeTe for assistance and the latter sent an army of 2,000 with 75 musketeers to crush Chicanda's rebellion. A successor of Chunzo named Matuzianhe rose up against Gatsi and drove the king out of his capital, reduced to desperation, Mutapa Gatsi mortgaged his kingdom's mines to the Portuguese at Tete in exchange for the throne.14

By then, the former vassal chiefdoms of Mutapa in the east such as Manyika, Barwe and Danda, broke away from the central control in order to wrestle control of the gold trade and gain direct access to the imported wealth.15 The Portuguese would later came to Gatsi's aid after Matuzianhe had attacked Tete, they drove off the rebel vassal, defeated many of his well-armed rebellious vassals from 1607-1609 by constructing fortifications, and constructed a permanent for with a garrison of soldiers at Massapa in 1610.16

After he was reinstalled in the capital, Gatsi quickly weaned himself off Portuguese control, he deceptively buried silver ores in his territory to lure his Portuguese allies, and exploited the divisions among the latter (whose stations at Tete, Mozambique and Goa were in competition), to expel them from the goldmines. After Gatsi demanded the kuruza annual tax from the very Portuguese who'd reinstalled him, the latter then turned to support his rivals, and in 1614, they mounted a failed attack on Mussapa. Gatsi had regained all the territories that Mutapa had lost and was in firm control of the state by the time of his death in 1623.17

Map of south-east Africa showing the distribution of its resources18

Map of Zimbabwe showing the distribution of Portuguese trading towns. the furthest among them are located more than 500km from the coast and were until the 19th century, the furthest settlements of Europeans in the central African interior.

Portuguese loop-holed field fort built on Mt. Fura near Baranda (massapa) in northern zimbabwe, to control the gold trade during the civil wars of the 1600s19

From the “king’s wives” to Conquistadors: the Portuguese conquest of Mutapa

king Gatsi had allowed Portuguese traders to establish several trading posts in the heartland of the Mutapa state called feiras, or trading markets, such as Dambarare, Luanze and Massapa. Most of them were built in areas under the control or influence of local rulers who had a stake in the trade and the Mutapa king could closely monitor the Portuguese' activities, as well as leverage the allied Portuguese in the feiras, against potential Portuguese invaders in TeTe and Mozambique island.20

Following the death of king Gatsi in 1624, his son Kapararidze ascended to the throne, but his legitimacy was challenged by Mavhura (the son of Gatsi's predecessor) and this dispute was quickly exploited by the Portuguese who supported the latter over the former. When Kapararidze ordered the execution of a Portuguese envoy for breaching protocol on travelling to the kingdom in 1628, the Portuguese retaliated with a massive invasion force of 15-30,000 soldiers and 250 musketeers in May 1629 that drove off Kapararidze and installed Mahvura.21

Mahvura was forced to sign a humiliating treaty of vassalage to the King of Portugal that effectively made Mutapa its colony on March 1629. The treaty allowed the Portuguese traders and missionaries complete freedom of activity without having to pay taxes, giving them exclusive rights over all the gold and (potential) silver mines in Mutapa, permanently expelling the Swahili traders who were competing with the Portuguese, and converting the entire court to Catholicism by the Dominican priests —the last of which was received with great enthusiasm by the papacy in Rome.22

The general population of Mutapa was strongly opposed to this, they rallied behind Kapararidze in a massive anti-colonial revolt, that attacked nearly all Portuguese settlements across the kingdom between 1630-1631, killing 300-400 armed settlers and their followers with only a few dozen surviving in Tete and Sena, and spreading into the neighboring regions of Manica and Maravi upto the coastal town of Ouelimane, which was besieged, driving the survivors back to the coast. They also captured and executed the Dominican priests who had converted Mavhura, an act that outraged the Portuguese colonial governor of Mozambique island.23

In response to this challenge of their authority, the Portuguese sent a massive army in 1632 under Diogo Meneses comprising of 200-300 Portuguese musketeers and 12,000 African auxiliaries, the invading force quickly reestablished Portuguese control over Quelimane and Manica, and marched into Mutapa, it succeed in defeating Kaparidze’s forces and reinstalling Mavura.24

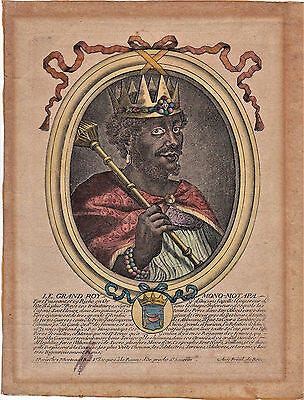

engraving titled; ‘Le grand Roy Mono-Motapa’ by Nicolas de Larmessin I (1655-1680) depicting a catholic king of Mutapa

The Portuguese colonial era in Mutapa.

The half-century that followed Meneses' campaign was the height of Portuguese authority in Mutapa and central Africa, with hundreds of traders across the various mining towns, and dozens of Dominican priests with missions spread across Mutapa and neighboring kingdoms, sending Mutapa princes to Goa and Portugal (some of whom married locally and settled in Lisbon25). The Portuguese also made a bold attempt to traverse central Africa with the goal of uniting their colonies that now included coastal Angola, coastal east Africa and most of north-eastern Zimbabwe and Mozambique.26

When Mavhura passed on in 1652, the priests installed king Siti as their puppet. Their power in royal succession remained unchallenged in 1655 with the ascendance of Siti's successor king Kupisa, who reigned until 1663 until he was assassinated, likely by an anti-Portuguese faction at the Mutapa court associated with his successor Mukombwe —a shrewd ruler increasingly behaved less like a vassal. Mukombwe recovered some of the lands and mines that his predecessors had handed over to the Portuguese, he invited Jesuit priests to counter the Dominicans, and threatened the Portuguese position in Mutapa so much that the governor of Mozambique island planned to invade Mutapa and depose him.27

But Mukombwe's shrewdness couldn't tame the decline of Mutapa. Like his predecessors, he failed to confine the Portuguese traders to the feiras, and the Portuguese settlers and traders are said to have devastated the Mutapa interior searching for slave labour to mine the goldfields and guard their settlements, as well as raiding the vassal chief's cattle herds for regional trade and to acquire more land and followers.28 .Catastrophic droughts are reported to have occurred in the mid 17th century accompanied by other natural disasters which depopulated north-eastern Zimbabwe and further undermined Mukombwe's position relative to his vassals.29

One Portuguese writer in 1683 described the sorry state of Mutapa during this period;

“Mocaranga (Mutapa) has very rich mines, but the little government, and the great domination of the Portuguese with whom the natives used to live together, has brought it to such an end, that it is depopulated today and consequently without mines. Its residents ran away, and the king appointed them other lands for them to live as it pleased him. The larger part of this kingdom remained without more people than the Portuguese and their dependents and slaves. It now looks the same that Lisbon will look with three men, but not to look completely deserted: the wild animals came in instead of the residents, and it has so many that even inside the houses the lions come to eat people.”30

portuguese governor's residence in Tete, by John Kirk c. 188031. This was constructed late in the 18th century, despite its importance to the portuguese the town remained rather modest

Decline of Mutapa and Changamire Dombo ‘s expulsion of the Portuguese.

In response to the political upheavals of the Portuguese era, several Mutapa vassals rebelled, one of these was Changamire Dombo, who had been granted lands and wealth by the king Mukombwe in the 1670s likely to pacify him. Changamire used the wealth to attract a large following and raise his own army primarily comprised of archers unlike most rebels of the time who were keen to acquire muskets. Mukombwe sent Mutapa's army to crush his rebellion but Dombo defeated them.32

In 1684, the emerging Rozvi kingdom's ruler Changamire managed to score a major victory against the Portuguese musketeers at Maungwe. Facing an army of hundreds of Portuguese musketeers and thousands of African auxiliaries, Dombo’s archers withstood the firepower in pitched battle, they crushed the Portuguese force and seized their firearms and trade goods33. Dombo then moved south to conquer the cities of Naletale and Danangombe, the latter of which became his capital the Rozvi kingdom.34

When king Mkombwe died in 1692, the Portuguese pushed to install their preferred catholic candidate named Mhande to the throne of Mutapa, instead of Mukombwe's brother Nyakunembire who was the more legitimate choice. The latter prevailed and his fist move was to appeal to Dombo for military aid to punish the insolate priests and traders. In 1693, Dombo's armies descended upon the Portuguese settlements of Dambarare whose destruction was so total, that the rest of the Portuguese who weren't captured by Dombo, and their peers across the kingdom, fled to Tete and Sena.35

Mhande later received Portuguese assistance in 1694 and managed to drive off Nyakunembire, who was instead installed as king of Manyika by Dombo. As the Portuguese were trying to re-establish their position in the interior, Dombo's forces descended on Manica in 1695 and sacked the Portuguese settlements there, sending refugees scurrying back to Sena.36

While Portuguese priests would continue attempting to influence the succession of Mutapa's rulers, the once large kingdom had been reduced to a minor chiefdom on the fringes of the vast Rozvi state, the latter would then assumed the role of Mutapa as the preeminent regional power in the interior and competed with the Portuguese to install puppets on Mutapa’s throne. In 1702 and 1712, the Rozvi deposed Portuguese-backed kings and installed their own candidates, this pattern continued until the Portuguese formally pulled out of Mutapa's politics in 1760,37 but Mutapa survived and recovered some of its power in the early 19th century.38

The Rozvi instituted a policy against Portuguese interference in regional politics including within their vassal chiefdoms. Their Portuguese captives from the 1695 wars were permanently settled in the interior and were to have no contact with the coast, despite repeated attempts to ransom them39. The Rozvi continued gold trade with the Portuguese traders, but confined the latter's activities to the feiras, enforcing this policy strictly using its fierce armies in I743, I772, and I78I by protecting the towns, greatly reversing the balance of power in the region.40

In the Rozvi's neighboring kingdom of Kiteve, Portuguese traders were expelled and their puppet king deposed in the early 18th century after rumors that he was planning to hand over its gold mines to them. The last of the Portuguese trading towns in the kingdom of Manica would later be razed in the early 19th century, and it would be nearly 60 years before the Portuguese resumed colonializing the region and finally completed their occupation of Mutapa in 1884.41

the ruins of Naletale

The ruins of Danangombe

one of four muzzle loading cannons from the Portuguese settlement of Dambarare found in the ruins of Danangombe long after it had taken by Changamire’s forces in 1693.

Conclusion: The military factor in African history.

It's difficult to overstate the formidable challenge that early conquistadors encountered on the African battlefield. While the initial losses of 1571 invasion force could be put down to their inexperience, which they made up for by recruiting African auxiliaries, their defeat by Changamire's forces in the 1690s and his destruction of Portuguese settlements in the region comprised the largest loss of European life in African war until the Italian loss in Ethiopia.

While disease may have presented a challenge to the Portuguese in Mutapa, it was never a sufficient barrier to prevent the kingdom's conquest; nor the permanent stationing of Portuguese garrisons in Tete; nor the unrestrained activities of Portuguese settlers in various mining towns deep in the interior of Africa. The principal factor behind the European retreat from south-east Africa was their military defeat --the same factor that had enabled their initial establishment.

Is Jared Diamond’s “GUNS, GERMS AND STEEL” a work of monumental ambition? or a collection of speculative conjecture and unremarkable insights.

My review Jared Diamond myths about Africa history on Patreon

if you liked this Article and would like to contribute to African History, please donate to my paypal

A Political History of Munhumutapa, C1400-1902 by S Mudenge pg 37-38

When science alone is not enough: Radiocarbon timescales, history, ethnography and elite settlements in southern Africa by Shadreck Chirikure, pg 365

A History of Mozambique by Malyn Newitt pg 80

New Perspectives on the Political Economy of Great Zimbabwe by Shadreck Chirikure pg 25-30

Port cities and intruders by Michael Pearson pg 49

A Political History of Munhumutapa, C1400-1902 by S. Mudenge, pg 182

Excavations at the Nhunguza and Ruanga Ruins in Northern Mashonaland by P.S. Garlake

Chisvingo Hill Furnace Site, Northern Mashonaland by M.D. Prendergast

A History of Mozambique by Malyn Newitt pg 55)

Portuguese Musketeers by Richard Gray, pg 534

A History of Mozambique by Malyn Newitt , pg 57-58)

A History of Mozambique by Malyn Newitt pg 59-60)

A History of Mozambique by Malyn Newitt pg 81)

The Zimbabwe Culture by Innocent Pikirayi pg 187)

Palaces, Feiras and Prazos by Innocent Pikirayi pg 165

The Zimbabwe Culture by Innocent Pikirayi pg 189)

A History of Mozambique by Malyn Newitt pg 85-88)

New Perspectives on the Political Economy of Great Zimbabwe by Shadreck Chirikure

Palaces, Feiras and Prazos by Innocent Pikirayi pg 175

Palaces, Feiras and Prazos by Innocent Pikirayi pg 166, A History of Mozambique by Malyn Newitt pg 99)

The Dominican Friars in Southern Africa by Philippe Denis pg 26)

The Dominican Friars in Southern Africa by Philippe Denis pg 27)

A History of Mozambique by Malyn Newitt pg 90, Portuguese Musketeers on the Zambezi by Richard Gray pg 532)

A History of Mozambique by Malyn Newitt pg 91-92)

A History of Mozambique by Malyn Newitt pg 95)

A Political History of Munhumutapa, C1400-1902 by S. Mudenge pg 274)

The Dominican Friars in Southern Africa by Philippe Denis 35, A Political History of Munhumutapa, C1400-1902 by S. Mudenge pg 275-277)

Portuguese Settlement on the Zambesi: Exploration, Land Tenure and Colonial Rule in East Africa by Malyn Newitt pg 62)

A Political History of Munhumutapa, C1400-1902 by S. Mudenge pg 277)

The Shona and the Portuguese 1575–1890. Volume I: 1570–1700, by David Beach pg 162

The Zimbabwe Culture by Innocent Pikirayi pg 210)

Portuguese Musketeers by Richard Gray, pg 533, A Political History of Munhumutapa, C1400-1902 by S. Mudenge pg 286

The Zimbabwe culture by Innocent Pikirayi pg 212-214, 205-208

The Dominican Friars in Southern Africa by Philippe Denis pg 36

The Dominican Friars in Southern Africa by Philippe Denis pg 38, A History of Mozambique by Malyn Newitt pg 104)

Portuguese Settlement on the Zambesi: Exploration, Land Tenure and Colonial Rule in East Africa by Malyn Newitt pg 72)

The Zimbabwe culture by Innocent Pikirayi pg 193

The Role of Foreign Trade in the Rozvi Empire: A Reappraisal by Mudenge pg 387

A History of Mozambique by Malyn Newitt pg 201

Portuguese Settlement on the Zambesi: Exploration, Land Tenure and Colonial Rule in East Africa by Malyn Newitt pg 72-75)

This was a very well written and infromative read. Thank you for sharing and including your sources I will be doing more reading into old emipres in Southern Africa!