The kingdom of Ndongo and the Portuguese: Queen Njinga and the dynasty of women sovereigns (1515-1909)

The effects of early colonial warfare in central Africa

Founded in the highlands of modern Angola near the Atlantic coast, the kingdom of Ndongo's political history was to be inextricably tied to Portuguese colonial interests in west-central Africa. For nearly a century, the armies of Ndongo battled with Portuguese in multiple wars that resulted in the loss of most of Ndongo's territory, until the rise of Queen Njinga ended the deepest colonial expansion into central Africa.

Njinga of Ndongo is the undoubtedly the best known Queen in pre-colonial Africa's history. During her remarkable reign, she was involved in dozens of wars with the Portuguese, and forged trans-regional alliances with the Kongo kingdom and the Dutch. She skillfully performed and manipulated several legitimating practices to overcome challenges to her rule that were based on her gender, and the precedent she set produced an equally remarkable dynasty of women with atleast 6 Queen regnants succeeding her —an exceptional number in World History.

This article outlines the history of Ndongo's wars with Portugal and the exceptional circumstances through which Queen Njinga managed to preserve her kingdom's autonomy and establish a dynasty of Women sovereigns.

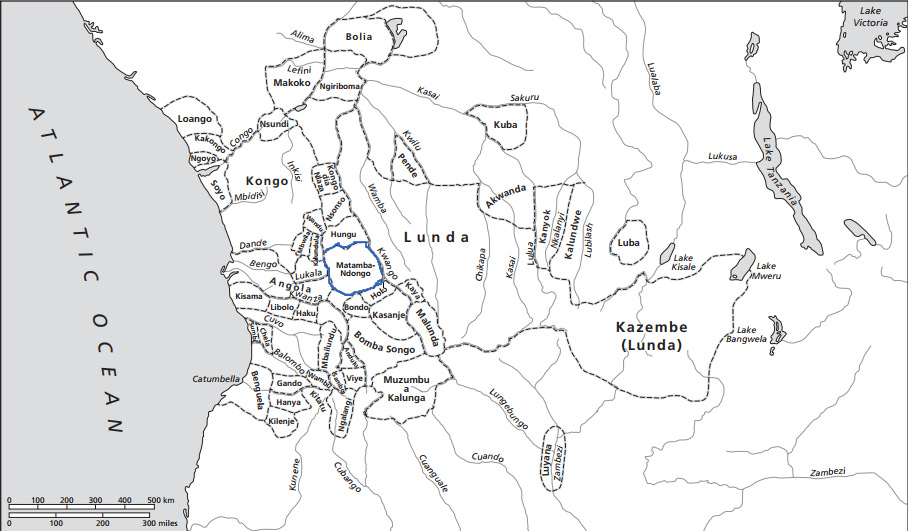

Map showing the kingdoms of Ndongo and Matamba in the early 16th century1

If you like this article, or would like to contribute to my African history website project; please support my writing via Paypal

An early history of the Ndongo and Matamba kingdoms, their relationship with Kongo and initial contacts with the Portuguese (1515-1580)

The kingdoms of Ndongo and Matamba were established in the early 16th century in the area south of the kingdom of Kongo in a region known as “Ambundo” named after its main language; Kimbundu. Ambundo was originally home to many small polities (murindas) of independent rulers that fought to expand their territory, and the most successful of them was Ngola (Angola) Inene whose dynasty ruled Ndongo. Traditions recorded in the 17th century claim Ngola Inene came from Kongo, but its equally likely this was simply meant to establish a prestigious genealogy.2 Both kingdoms were originally vassals of Kongo during its king Afonso I's reign when Matamba is recorded sending tribute of silver manilhas to Mbanza Kongo in 1530, and Ndongo received envoys from Portugal possibly after receiving permission from Afonso in 1520. But the exact nature of this vassalage is ambiguous as both states acted with near complete autonomy.3

Ngola Inene was succeeded in by Ngola Kiluanje (r.1515–1556) who established his capital at Kabasa, and expanded Ndongo's control over the lands north of the Kwanza River, bringing more Ambundo states under its orbit and away from Kongo, but he still accepted Kongo's nominal suzerainty including sending ambassadors to Afonso in 1518 to become Christian, before sending them to Portugal. By the 1520s, Ndongo occasionally bolstered its military with Portuguese mercenaries during its earliest expansion. The Portuguese had begun trading around Luanda and up the Kwanza river but Kongo's Afonso was opposed to their involvement in Ndongo which he considered a vassal. During the time of Ndongo's expansion which saw the conquest of the provinces of Ilamba and Kisama, Afonso is recorded launching campaigns to the same region in 1513 and 1516 in reaction to this expansion.4

In 1525 the Portuguese embassy that had arrived in Ndongo 5 years earlier was detained by Afonso, ostensibly, to protect them. It was soon after this that he sent his now famous letter to the Portuguese king complaining about the Portuguese traders' subversive activities among his vassals and that they were seizing “our natives, sons of the land and the sons of our noblemen and vassals and our relatives.” This complaint has often been misinterpreted by some scholars who see Afonso as a forerunner to the anti-colonial African leaders of the 19th century, but this interpretation bestows on Afonso a motive and sense of purpose which he would have had difficulty in recognizing, as Kongo was not a Portuguese colony, nor would Portuguese attempt any colonial invasions in central Africa until 1571. Afonso's letter was instead intended to assert Kongo's claim over Ndongo inorder to control the latter's foreign relations by directing Portuguese activities to Ndongo solely through Kongo. Afonso and his successor Diogo's attempt at controlling Ndogo's politics were fruitless, even after Diogo's campaigns to pacify Luanda included Portuguese traders among the war captives he took back in 1548 and 1549.5

Undeterred, Ndongo's king Kiluanje sent another embassy to Portugal in 1549 for religious and political reasons, as well as to sever Kongo's claim over the coastal region adjacent to it but the mission was detained for 9 years in Sao Tome, the response mission arrived in 1560 to find that King Kiluanje had been replaced by Ndambe (r.1556–1561), and later by Ngola Kiluanje kia Ndambe (r.1561–1575).6 The mission however, only consisted of priests and thus didn't achieve all that Kiluanje hoped for but king Ngola Kiluanje kia Ndambe nevertheless hosted it generously. Diogo's successor Bernardo sent Ngola Kiluanje kia Ndambe a letter in 1562 warning him that the Portuguese were only there “to see if Ndongo had silver or gold in order for the King of Portugal to take the land” and that only he (Diogo) should be incharge of of trade with them. Despite the clearly selfish motive of the warning, Ngola Kiluanje kia Ndambe heeded Diogo's advice as the religious mission was of little use to him, he detained and later expelled the Portuguese, save for a few priests. He continued expanding the kingdom westwards to the Atlantic, and southwards to the Benguela kingdom, which he conquered in 1563 although his successors had lost it by 1586. By this time, Matamba had fully broken off from Kongo in 1560 but its relationship with Ndongo was unclear.7

The kingdom of Ndongo was by the mid-16th century a relatively centralized state compared to the preceding Ambundo polities it had subsumed, but less so compared to the Kongo kingdom. Its administration consisted of core provinces ruled by subordinate royals controlling conquered polities, and in its peripheries were subordinate kings who sent soldiers and tribute but otherwise had local sovereignty8. Like many states in west-central Africa, it was largely established by concentrating populations around a central core ruled by a hierarchical administration including '"makotas” who elected the King, “sobas” who led the provinces, and a litany of officials. The King's legitimacy, as considered by the electors, rested on a complex mix of practices including his lineage, his capacity to archive victories in war and accumulate resources for redistribution among the nobles, and his spiritual position in Mbundu cosmology.9

Ndongo's subjects primarily included the "ana murinda" (citizens), who paid taxes/tribute, and the "kijiko" (Serfs) who were dependents of the citizens, living in their own villages and farmed for both themselves and the royal court but couldn't be sold. It also included "mubika" (captives) acquired during its wars of expansion/rebellion that could be retained or sold. The very fragmented nature of the Ambundo region in which Ndongo was just one of many expansionist states, explains why the region was a major source of captives. Ndongo’s economy however, like all others in the region, was largely rural and agricultural, with significantly more cattle rearing than in Kongo, and a small specialist industry in textiles.10

The kingdoms of Ndongo and Matamba in 1550, and their known neighbors

Ndongo’s wars with Portugal and the founding of the Angola-colony

Internal threats in Kongo forced Álvaro's to request Portugal's assistance, and the latter sent two missions that would lead to a greater military engagement by Portugal in west central Africa. Kongo had granted Luanda in exchange for Portugal’s assistance, and also offered to assist the second Portuguese mission in its objective of colonizing Ndongo. (The number of Portuguese soldiers for these two missions was 600, assisted by 10-12,000 African auxiliaries, i won't be quoting each force's might for each battle below so assume an average force of 300-400 Portuguese, and 8-12,000 Africans allies, against an average force of 10-15,000 soldiers and 300 musketeers of Ndongo or Kongo). The commander of the first Portuguese mission to Kongo went back after assisting Kongo in 1574, leaving his forces to be used by both Kongo and Ndongo as mercenaries. Additionally, the region of Luanda was returned to Kongo by 1576, although it would later be retaken by Portugal to serve as their colonial capital for Angola.11

Portugal's second mission under Dias de Novais saw slightly more success since a succession crisis in Ndongo that saw Njinga Ngola Kilombo (r.1575–1592) rise to the throne, made the king to request Novais' assistance to quash rebellions in Ilamba province, but just like Kongo's king Alvaro had done, Ndongo's king Kilombo turned on the Portuguese as soon as he was secure. His army killed the Portuguese in their ranks, with only few surviving to flee back to Novais' camp12. Seeing that they were weak, Alvaro offered to assist the Portuguese hoping to conquer Ndongo himself, but the combined Kongo-Portugal army was crushed by Ndongo in May 1580 at the battle of Bengo.13

Novais nevertheless managed to ally with Ndongo's rebels in Ilamba and other provinces near the coast, prompting Ndongo to attack the alliance in August 1585 at the disastrous battle of Kasikola which Ndongo lost, leaving ilamba under Portuguese control. The Portuguese then built a small fort at Massangano. The Portuguese commander Novais was succeeded by Luis Serrão as governor of Luanda after his death in 1589, and the latter continued his predecessors' plans to colonize Ndongo. the kingdom of Matamba also reappears at this point in an alliance with Ndongo, and the two armies, led by Ndongo's king Kilombo descended upon the Portuguese and their allies at Lukala river in December 1589 and nearly annihilated them, forcing them back to Massangano.14

The Portuguese at Luanda under Francisco de Almeida would send another force in 1594 to Ndongo's southernmost province of Kisama but this too was defeated.15 To its south, Ndongo had its brief control over Benguela which by 1586 had sent a mission to Novias' camp but the mission was intercepted by Ndongo and defeated in 1587, although Benguela remained independent16. In Benguela's immediate hinterland, a new marauding political force called the Imbangala emerged that profoundly altered the region. The Imbangala weren't sedentary but wandered from place to place and lived by pillaging palm wine, seizing cattle, and recruiting soldiers and they acquired a very reputation in the west-central African kingdoms. They attacked Ndongo's vassals in 1600 and reached the coast where they sold some of their captives and some formed alliances with the Portuguese. However, the Imbangala never formed a permanent alliance with any party and would frequently change sides as it suited them17.

Ndongo was under a succession crisis after the death of king kilombo, who was succeeded by Mbande a Ngola Kiluanje (r.1592–1617), his provincial armies were engaged in battles with the Portuguese and their allies who built another fort at Cambambe in 1603.18 In 1617, King Mbande was assassinated by his nobles. And while the electoral council of Ndongo had chosen its own successor, one of the deceased king's sons named Ngola a Mbande seized the throne and killed the nobles who opposed him. Sensing opportunity to conquer Ndongo, the Portuguese under Mendes de Vasconcelos formed an alliance with the Imbangala bands including Kasanje, and a rival candidate for the Ndongo throne named Mubanga who'd allowed them to build a fort at Ambaca (the furthest control in the interior). In 1618, they defeated Ndongo's forces and forced the king to flee, he later returned and besieged the Portuguese forts, prompting them to send another campaign in 1621 that forced him out to the Kindonga Islands, the imbangala went further inland, pillaging Matamba and selling captives to the Portuguese.19

The Portuguese failed to place a puppet on Ndongo's throne as no candidate had sufficient support while the king was at large. Taking advantage of the arrival of a different Luanda governor, King Ngola Mbande sued for peace in 1622, sending his three sisters Njinga, Kambu (Barbara), and Funji (Graça) to negotiate for him in Luanda, regaining his throne and provinces in exchange for peaceful relationship. Njinga had shrewdly chosen to convert as a way of assuring the Portuguese but this turned out to be superficial. The roaming Imbangala remained a threat to Ndongo, but King Ngola Mbande managed to ally some Imbangala bands such as Kasanje against other bands.20

Njinga’s baptism in 1622, by Antonio Cavazzi, ca. 1668

Furthest extent of Portuguese expansion into the interior of west-central Africa for over three centuries.21

“Forte de Nossa Senhora da Vitória de Massangano"22. at the height of the Ndongo invasions, such forts usually held a few hundred Portuguese soldiers surrounded by thousands of African allies.

The reign of Queen Njinga (1624-1663)

The chosen successor of King Ngola Mbande was his 7-year old son who he had left with the support of the Kasanje band leader named Kasa; even though Njinga was the more capable candidate, especially since she had fought to defend Matamba during the 1620s invasion, turned some more enemy Imbangala into allies, and secured a peace treaty with Portugal.23 Unlike Ndongo's earlier succession crisis however, the Portuguese chose not to intervene because of a number of defeats they had suffered during this time. Emboldened by their victory over Ndongo in 1618-1620 and their newfound Imbangala allies, the Portuguese thought they could invade Kongo as well. They sent an army in 1622 that after a small initial victory at Mbumbi, was crushingly defeated by Kongo's royal army at the battle of Mbanda Kasi.24

Njinga had been involved in military campaigns so that she was well known in the army, was allowed her to sit in on affairs of state, and her skill as a diplomat was widely known, but some elites balked at the idea of a female ruler. Judging her candidature to be weak, Njinga initially chose to rule as a regent to the boy-king, styling herself as “Lady of Ndongo” rather than Queen. But when the boy-king died by 1625, Njinga, who was widely suspected to have been responsible, took on the title of Queen and begun to rule with full power. While she faced challenges to her legitimacy as a woman —with few historical precedents in both the traditional and Christianizing states of the region of a woman sovereign— her skillful manipulation of several legitimating devices gradually enabled her rule to be accepted, and arguably the most significant of these would be her wars against the Portuguese.25

Njinga's rule was opposed by Mubanga (mentioned above) who allied with another powerful noble named Hari a Kiluanje, who inturn allied with the Portuguese of Luanda under Fernão de Sousa and occupied the Ambaca fort. The Ndongo kingdom was invaded by de Sousa's allied force in 1626, forcing Njinga out of the kingdom, and enthroning Hari a Kiluanje's son Ngola Hari (after the former had died)26. But unable to hold the country, the Portuguese withdrew a year later enabling Njinga to return and send several embassies to Luanda and Kongo pressing her claim. Kongo's king Ambrósio accepted it and sent gifts recognizing her but the Portuguese made plans for war.27

Njinga was again faced with a Portuguese invasion in 1629 but some of her allies had abandoned her; including the Kasanje leader Kasa who went north to Kongo but was driven back. Her forces were defeated after a lengthy battle, her sisters were taken as hostages, and she was forced to flee to join with Kasa's forces. But since Kasa as an Imbangala leader would only accept Njinga into his band without her forces, she chose to become an Imbangala herself, accepting recruited soldiers into a separate command under her senior commander ('Njinga Mona') who became her subordinate and was expected to succeeded her according to Imbangala custom28. Njinga thus turned to Matamba, the old ally of Ndongo, and brought it under her control by 1630. She then launched a re-conquest of Ndongo facing off against the Portuguese in several battles and skirmishes nearly every year from 1630-1650. By the year 1635 retaken the islands of Kindonga. Njinga begun holding Portuguese traders hostage to release her sisters and sent agents to Luanda in 1637 to normalize relations. some of her former kasanje allies moved south and established their own state.29

After the Portuguese lost to a combined Kongo-Dutch force in 1642, Njinga pressed her forces forward and retook nearly all of Ndongo, but this drove the Portuguese to create new allies to prepare for war, choosing Ngola Hari as their candidate for Ndongo's throne.30 Njinga faced off with a Portuguese force in 1644 and defeated it taking many captive including Portuguese soliders and missionaries, but the Portuguese counter-attacked in 1645-6 and while she had driven them off and captured their supplies, her dispersed army was attacked and defeated. Njinga returned with a much bigger allied army that included Kongo's forces and the Dutch, the combined allied army defeated the Portuguese and their allies at Kumbi in October 1647, again at Ilamba in August 1648, and laid siege to their river fort of Massangano for a month. After Portuguese reinforcements arrived and bombarded Luanda, the Dutch signed (another) peace treaty with them, the relief force's commander Correia de Sá sent letters to Kongo's king Garcia and Ndongo's Njinga imploring them to make peace, judging his forces insufficient to retake the interior.31

Queen Njinga with captured missionaries32

Map showing the Ndongo-Matamba kingdom during Njinga’s reign

Feeling secure in her position as Queen of Matamba and Ndongo, Njinga begun rebuilding her kingdom. Since her former allies of Kasanje had turned hostile in the 1630s, so she encouraged runaway slaves and mercenaries to join her army thus drew the few remaining Imbangala to serve under her command.33 Hoping to solve her succession conflict with Ngola Hari (who was pushing his Portuguese allies to invade Ndongo), and institutionalize the Imbangala, Njinga devised an elaborate religious strategy to convert to Catholicism through the auspices of a Kongo missionary whom she captured in 1648. She requested more missionaries to come in 1651, proposed a peace treaty with Luanda in 1654, and documented miraculous apparition that she claimed were incomprehensible to her traditional religious advisors but that compelled her to convert to Christianity. The Luanda governor eventually signed a peace treaty with Njinga, released her sister in 1656, withdrew support of her rival Ngola Hari, and the Queen became Christian.34

In January 1657, Njinga summoned her army and informed it that she had ceased the endless campaigns after signing a peace treaty with Portugal, and except a skirmish with Kasanje in 1661, the kingdom of Ndongo-Matamba remained at peace until her death in 1663.35 In her ceremonies in Ndongo-Matamba, and in negotiations with the Portuguese in 1655 she was careful to demand that all recognize her sister Barbara as her heir, and knowing that neither she nor Barbara would have any children, she promoted a royal named Joao Guterres Ngola Kanini as Barbara’s husband inorder to ensure that a member of the nobility related to her would continue to rule instead of her very powerful Imbangala general Njinga Mona.36

Queen Njinga with bow and arrow and battle ax, by Antonio Cavazzi, ca. 1668

Letter written by Queen Njinga’s to Father Serafno da Cortona, August 15, 1657

Njinga’s successor Queens: the kingdom of Ndongo-Matamba from 1663-1909

Njinga was succeeded by her sister Barbara who, already old, reigned only briefly upto 1666 when she died. A succession dispute involving a complex set of alliances brought Njinga Mona briefly in power until 1669 when he was ousted in favor of Barbara's husband João Guterres, but his death led to the brief return of Njinga Mona before he was ousted again in favor of Francisco in 1671. During this time, the southernmost provinces of Ndongo we split between the Portuguese and the Matamba-Ndongo king Francisco after a peace treaty and the capture of João II, the successor of Ngola Hari, now a former ally-turned-rebel. This ended direct Portuguese campaigns against Ndongo for nearly a century.37

With the threat of a hostile state of Kasanje still looming in Ndongo-Matamba's south, Francisco used the opportunity of succession dispute to place an ally on its throne in 1680, but this was short-lived, and a rival candidate gathered allies including the Portuguese to fight Franscico's forces but the Portuguese were defeated in battle in 1681 and their captain was killed. Franscisco also died shortly after this war and was succeeded by his sister Verónica Kandala ka Ngwangwa (r.1681-1721). Veronica revised her alliance with the Portuguese inorder to isolate Kasanje in a treaty she signed in 1683. The queen initiated further expansion by moving against Kahenda in the Dembos region (between Kongo and Angola-colony) in 1688, but decided to consolidate Ndongo-Matamba.38 While few of her successors were engaged in further expansion, the kingdom that Njinga and Verónica left behind was no longer the weak, beleaguered state that was about to be swallowed up by the Portuguese colony; instead, Ndongo-Matamba would remain a major central African power in the 18th century, surviving the expansion of the Lunda empire.

Verónica’s succession marked a continuation of female rule begun by Njinga, as her successors included the Queens; Ana II (r.1742-1756) , Verónica II (r. 1756-1759), Ana III (1759-1764) and Kamana (1800-1810)39Matamba had again faced off with the Portuguese early during the reign of Ana II in 1744 partly due to rival factions requesting for Portuguese aid but also because the kingdom had blocked trade and attacked the Portuguese market at Cabambe, the Portuguese sent a large force of 26,000 but Ana had retreated from her capital. As the Portuguese were running short of supplies, Ana's envoys were sent to negotiate a treaty, which was accepted and the Portuguese withdrew.40 Matamba would continue attacking Portuguese markets in 1755, but the Portuguese were unable to retaliate with any degree of success, the 1744 campaign would be the last major invasion into Matamba until 1909.

Map of west-central Africa in 185041

Conclusion: Ndongo’s place in African history

The kingdom of Ndongo presents us with many exceptions in African history. As the site of the first and longest-lasting European colony outside north-Africa, the politics of Ndongo were determined as much by internal factors as they were by external actors. The Portuguese had advanced more than 150km into the interior where they would remain for over three centuries, and their colonial threat had a significant influence on the trajectory of Ndongo's history. The devastating invasions in which Ndongo's land was seized and many subjects were enslaved, created the unusual circumstances for the rise of Queen Njinga.

Once Njinga had secured her power by permanently ending the Portuguese advance and uniting Ndongo with Matamba, her remarkable feat legitimized her contested reign as Queen. Njinga's shrewd political maneuvers in empowering her sister Barbara as her successor, established a dynasty that successfully preserved Ndongo-Matamba's hard-worn independence, and her precedent enabled the uncontested rule of women as sovereigns.

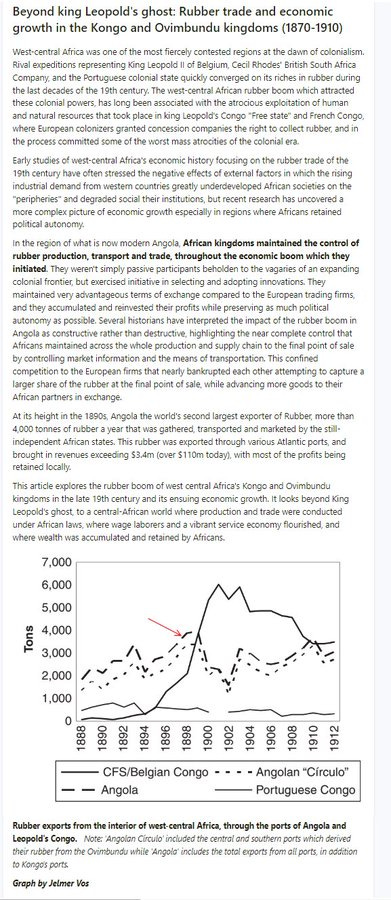

While King Leopold was brutally exploiting African labour of the ‘congo free state’ to obtain rubber, the same commodity was bringing alot of wealth to Africans in the independent kingdoms of Kongo and Ovimbundu, right next door.

read about it here;

If you like this article, or would like to contribute to my African history website project; please support my writing via Paypal

taken from Linda Heywood’s ‘Njinga of Angola’

A History of West Central Africa to 1850 by John Thornton pg 23, 43, 56-57

Njinga of Angola: Africa’s Warrior Queen by Linda Heywood pg 7

A History of West Central Africa to 1850 by John Thornton pg 58, 54)

A History of West Central Africa to 1850 by John Thornton pg 55, 67)

Njinga of Angola: Africa’s Warrior Queen by Linda Heywood pg 19

A History of West Central Africa to 1850 by John Thornton pg 68-70)

Legitimacy and Political power by J.K.Thornton pg 29

Njinga of Angola: Africa’s Warrior Queen by Linda Heywood pg 9-14

A History of West Central Africa to 1850 by John Thornton pg 70-74, 94)

A History of West Central Africa to 1850 by John Thornton pg 82).

Central Africans, Atlantic Creoles, and the Foundation of the Americas by L. Heywood pg 86

A History of West Central Africa to 1850 by John Thornton pg 85

A History of West Central Africa to 1850 by John Thornton pg 87-89, pg 92-93, Njinga of Angola: Africa’s Warrior Queen by Linda Heywood pg 28

A History of West Central Africa to 1850 by John Thornton pg 101)

A History of West Central Africa to 1850 by John Thornton pg 103)

Converging on Cannibals by Jared Staller pg 76-102, Legitimacy and Political power by J.K.Thornton pg 32

Njinga of Angola: Africa’s Warrior Queen by Linda Heywood pg 35-36

Njinga of Angola: Africa’s Warrior Queen by Linda Heywood pg 46-48

A History of West Central Africa to 1850 by John Thornton pg 117-122)

this and other maps in the article are taken from Linda Heywood’s ‘Njinga and Angola”

Njinga of Angola: Africa’s Warrior Queen by Linda Heywood pg 60-61

A History of West Central Africa to 1850 by John Thornton pg 130-131)

Legitimacy and Political power by J.K.Thornton pg 37-40

Njinga of Angola: Africa’s Warrior Queen by Linda Heywood 79-84

A History of West Central Africa to 1850 by John Thornton pg 150-152

Legitimacy and Political power by J.K.Thornton pg 32

Njinga of Angola: Africa’s Warrior Queen by Linda Heywood pg 114 A History of West Central Africa to 1850 by John Thornton pg 151-156)

A History of West Central Africa to 1850 by John Thornton pg 165)

A History of West Central Africa to 1850 by John Thornton pg 169-170, Njinga of Angola: Africa’s Warrior Queen by Linda Heywood pg 140-157

this and other pictures are taken from Linda Heywood’s “Njinga of Angola”

Njinga of Angola: Africa’s Warrior Queen by Linda Heywood pg 160-162

Njinga of Angola: Africa’s Warrior Queen by Linda Heywood pg 165-192

A History of West Central Africa to 1850 by John Thornton pg 178-182)

Legitimacy and Political power by J.K.Thornton pg 33

A History of West Central Africa to 1850 by John Thornton pg 186-188)

Conflitos na dinastia Guterres através da sua cronologia pg 28-31, A History of West Central Africa to 1850 by John Thornton pg 208-209)

Conflitos na dinastia Guterres através da sua cronologia pg 37

A History of West Central Africa to 1850 by John Thornton pg 240-241

J.K.Thornton

Great article, and a useful source