The legacy of Kush's empire in global history (755–656BC): on the "blameless Aithiopians" of Herodotus and Isaiah, and race in antiquity

The origin of the positive descriptions of Kush and "Black African" people in classical literature

In the 8th century BC, the kingdom of Kush made a spectacular entrance on the scene of global politics from their heartland in Sudan. The rulers of Kush expanded their control over 3,000 kilometers of the Nile valley and surrounding desert upto the region of Palestine, appearing as the legitimate pharaohs of Egypt which they ruled over for nearly a century. This dynasty of Nubian origin etched their legacy in the annals of history, marking Kush's introduction into classical literature.

Kush was the Egyptian name for the kingdom of Kerma (2500-1500BC) first used in 1937BC1 during Egypt’s “middle kingdom” era, after the 8th century BC, it appears as Kusu in Babylonian and Assyrian literature, as kus in Hebrew2, as Aithiopia and Ethiopia in Greek and later roman literature3 .(This is not to be confused with modern Ethiopia4 and the word "Kushite" as i use it below shouldn't be confused with “cushitic” speakers in the horn of Africa). The literal meaning of the motif Kush/Aithiopia in all classical documents from these places pointed to both the African nation of Kush and its people. It attimes included a particular reference to their skin color and their geographic location as the furthest known place at the time.

From these classical writings, the consensus among historians of classical literature is that the Kush and its people were portrayed in positive light, most notably in the anthropological and political descriptions of Kush written by Greek and Hebrew (biblical) authors. Greek authors’ description of Aithiopians tapers towards a utopian ideal, depicting the people of Kush as “blameless”, “pious”, “visited by the gods”, '“long lived”, “tallest and most handsome of all men” as written by Homer and Herodotus5 in the 8th and 5th century BC. In biblical accounts, Kush is described "throughout the Hebrew bible as politically, economically and militarily strong"6 and Kush’s people as descried as "a nation which tramples down with muscle power", "a people feared far and wide", "a tall, smooth nation" (Isaiah 18) with references to Kush's wealth (Isaiah 43:3, 45:14) and its military prowess (Ezekiel 38:5 and Nah 3:9). Kush’s positive biblical description “reflects the Israelite perception of this black African nation as a militarily powerful people, a feared people with muscle power, tall and good-looking"7

More importantly, these positive descriptions of Kush were written between the 8th and 6th century BC and are often explicitly describing Kush's 25th dynasty (r. 755-656BC). Its rulers Sabacos and Sethos in Herodotus’ “histories”, are the Greek rendering of the names of Kings Shabaqo and Shabataqo of Kush, and the biblical Tirhaka is the Hebrew rendering of King Taharqa of Kush. Classical authors mentioned not just the political history of these kings’ reign but the important role Kush played in the politics of the eastern Mediterranean. In their portrayal of Kush as civilized, some classical authors even claimed that Egyptian civilization is derived from Kush; with Agatharchides of Cnidus writing that: "the customs of the Egyptians are for the most part Aithiopian, for to consider the kings, gods, funeral rites and many other such things are Aithiopian practices, and also the style of their statues and the form of their writing are Aithiopian"8 This positive description influenced scholars as recently as the 19th century who claimed that Meroe (the capital of Kush) was the very origin of not just Egyptian civilization but of Greek and Roman civilization as well! with Hoskins writing that "Aithiopia was the land whence the arts of learning of Egypt and ultimately of Greece and Rome, derived their origin".9

Within these classical author's descriptions of Kush; both realistic and fanciful, lies the legacy of the 25th dynasty. Its power, wealth, the virtuousness of its rulers and character of its people that lingered in classical thought long after Kush itself had withdrawn from Egypt to its heartlands in Sudan. These positive accounts of an “Black-African” state of antiquity stand in marked contrast with later descriptions of African states and people that increasingly came to include sentiments that are considered racialist. The lauding of the Kushites' might, character and appearance also stands in contrast with classical descriptions of foreign states and people in Greek and biblical literature that was often unfavorable10.

This article provides an overview of the political history of the Kushite empire ( 25th dynasty Egypt), explaining why the generally positive memory of imperial Kush and its people was the direct consequence of the role this “Black-African” kingdom played in global politics, creating a legacy that was preserved by classical writers who described them in favorable light.

Map of the kushite empire

Support AfricanHistoryExtra by becoming a member of our Patreon community, subscribe here to read more about African history, download free books, and keep this newsletter free for all:

The Origins of Kush: from the kingdom of Kerma (2500BC-1500BC) through New kingdom Egypt (1550BC-1070BC)

The foundations of Kush were laid by the kingdom of Kerma; which from 1750 to 1550BC covered more than 1,200 km of the middle Nile valley between Aswan (in Egypt) and Kurgus (in central Sudan) becoming the "the First Empire of Kush, the largest political entity in Africa"11 and its from Kerma that many of Kush's cultural aspects are derived such as its forms of governance, religious practices and iconography. The kings based at the city of Kerma grew their kingdom through consolidating several Nubian states and by the early 16th century BC had subsumed states as far away as ancient punt (in northern Ethiopia) their growing military power enabled them to march their armies into Egyptian territory as far as Asyut (in central Egypt) and taking over parts of southern Egypt which they controlled for a century12 , by the turn of the 15th century BC however. the less centralized nature of Kerma's control over its vassal states was the catalyst of its downfall as successive Egyptian incursions chipped away parts of its empire until they reached the city itself in 1500BC although it wasn't until late in Thutmose III's reign in 1432BC that the Kerma ceased to exist and was incorporated into "new kingdom" Egypt.13

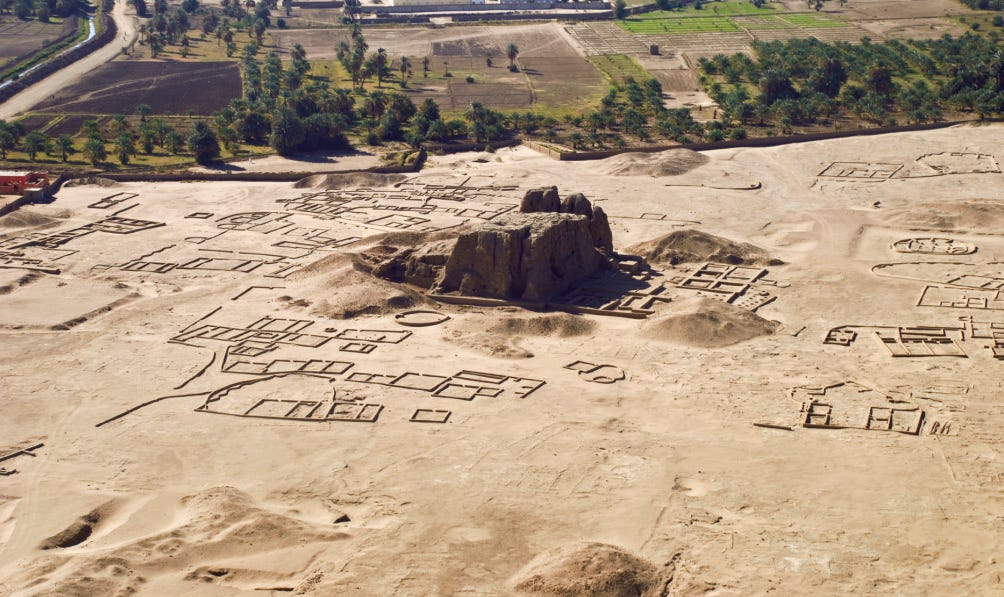

ruins of the city of Kerma in sudan

Under “new kingdom” Egypt, the social stratification and territorial political structures that existed in the Kerma empire were maintained but integrated into the political and economic administration of Egypt's “viceregal” Nubian province (Nubia will be used here to describe the geographical region in Sudan formerly dominated by Kerma) allowing sections of the Nubian elite to engage in what has been described as a "Janus-faced acculturation processes" that involved partial egyptianisation14, although most of the middle and lower class sections continued in their native customs and periodic rebellions fomented by the latter drove attempts by the Nubian elites to re-assert their independence. When the Egyptian control over Nubia declined in the 12th century BC, viceregal Nubian disintegrated into smaller polities identical to its original viceregal units which inturn were based on the vassal states as were organized under Kerma, but given the Nubian elite's experience with imperial administration and the inheritance of social-economic structures that worked best on an imperial scale, a re-integration of these disintegrated Nubian states was begun that would merge them under the authority of autochthonous rulers whose capital was at el-kurru in Sudan in the 10th century BC15.

At el-kurru, the Nubian rulers used bed-burials, tumulus tombs and practiced Nubian funerary rites, all of which were following the ancient Kerma-n customs, they also gradually and consciously begun a process of amalgamating Egyptian customs and iconography into Nubian customs, most notably the pyramid-on-mastaba superstructure (which was unknown in contemporary Egypt but was instead modeled on the pyramids of viceregal Nubian princes)16, and the re-emergence of Nubian ram-headed deity; Amun (of Napata) as part of the royal legitimation process and the new ideology of power17 this amalgamation was complete by the 8th century BC and is first attested under the Kushite king Alara who ordinated his sister Pebatma as the priestess of Amun (an important office that was central to succession in Kush) and begun reconstructing the Amun temple at Napata18. By the time of his reign in the early 8th century BC the kingdom based at el-kurru expanded to control a territory stretching from Meroe in Sudan to Qsar Ibrim in Egypt.

the royal necropolis of el-kurru in Sudan

The Kushite empire: control of Egypt and zenith.

The reign of Kashta (770BC-755BC): the role of religion in Kush’s ascendance

Kashta's reign in Kush begun around 770 BC and his appearance in Egypt was marked by the installation of his daughter Amenirdis I as the "God's wife of Amun elect" at Thebes in 756BC in “upper Egypt” this ‘office of divine adoratrice’ was important in the governance of upper Egypt. Kashta’s appearance in Egypt was determined by the latter’s political fragmentation; from the decline of during egypt’s 21st dynasty in the 11th century BC and the rise of the 22nd dynasty of libyan origins (r. 945-715BC) Egypt had become increasingly decentralized and fragmented polities emerged as a number of independent chieftains established their own dynasties especially in lower Egypt (the Nile delta region) but a faint ideology of unity was maintained by the theology of the Amun's direct kingship hence the importance of the institution of the divine adoratrice of God's wife of Amun of Thebes that secured the legitimacy of Pharaohs of this period19.

Amenirdis's installation therefore marked the formal extension of Kushite power into Egyptian territory not through conquest but by "courting the allegiance of pre-existing local aristocracies and countenancing their cross-regional integration through diplomatic marriages and ritualized suzerainty"20 This style of Kushite governance was most likely analogous to the political system of Kerma and remarkably similar to medieval Sudanic states, it was dictated by ecological, geographical and demographic conditions in the region but was wholly unlike that of the beauractraic Egyptian kingdom which it was now gradually subsuming. In this case, courting the allegiance of local pre-existing aristocracies was done by having the incumbent God's wife of Amun named Shepenwepet I adopt Kashta's daughter and retaining the descendants of the 23rd dynasty (who had ordinated Shepenwepet I) in high social status. The Kushite rule in Egypt is therefore traditionally dated to 755BC with an inscription at elephantine (in Egypt) of a ruler of Kush styled as "king of upper and lower Egypt, lord of the two lands, Kashta" marking the formal beginning of Kush's rule in Egypt, this is also the same year when Kashta's successor Piye ascended to the throne.21

The reign of Piye (755BC-714BC): benevolence and military prowess

On Piye’s ascension, he immediately assumed a five-part Egyptian-style titulary and inscribed this on a monumental stela that he set at Napata in his third regnal year, Piye’s titles were similar to the titles of Pharaoh Thutsmose III (1479-1425C) in which the latter was announcing his victories in Asia and Nubia's surrender - that he also inscribed on a stela displayed in Napata (this is the same Thutmose III mentioned in the introduction as the pharaoh that oversaw the final defeat of Kerma) Piye was openly announcing "a momentous reversal of history"!22

The use of Egyptian titles and Egyptian script as a means of articulating Kushite ideology of power was essential not just for integrating Egypt into the Kushite realm but for enhancing the legitimacy of the Kushite rulers as Pharaoh, and the in this reversal of history "the very symbols that were used by New Kingdom Egypt to integrate Kush into its realm were then re-deployed during the 25th dynasty to integrate Egypt into a Kushite realm"23 .The Egyptian script was far rom a Kushite invention but the copious amount of documentation produced by the Kushite kings of the 25th dynasty compared to their immediate predecessors and successors is perhaps the origin of the classical claim that egypt’s script came rom Kush. In Piye's monumental inscription he declared that "Amun of Napata has granted me to be ruler of every foreign country, Amun of Thebes has granted me to be ruler of kmt (Egypt), He to whom I say "you are chief" he is to be chief. He to who I say "you are not chief" he is not chief…" stating his imperialist perspective of royal power and his duty of expanding Kush, while also allowing for the accommodation of existing rulers who accept his rule as subordinate chiefs.24

Piye’s monumental inscription depicting him receiving the submission of Egyptian chiefs, this is the longest royal inscription written in egyptian hieroglyphs

Piye's armies advanced leisurely into Egypt in his 20th regnal year with him at the head of his army, defeating and acknowledging submission of more than 15 Nile delta chiefs such as Tefkent and Orsokon IV, Piye's kingship was confirmed by all egyptian chiefs, at all the three major Egyptian cities of Thebes, Heliopolis and Memphis and by all three major deities of the Egyptian state: Amun of Thebes, Ptah at Memphis and Re at Heliopolis, Piye went back to his capital at Napatan in Sudan but retained the subordinate Egyptian chiefs in their positions but under his authority.25 Piye's conquest coincided with the aggressive expansion of the Assyrian state under Tiglath-Pileser III in the 730sBC who had absorbed city-states in Syria-Palestine and cemented his rule with mass deportations of their populations, his successor Sargon II then destroyed the (northern) kingdom of Israel by 720BC despite the aid of the Orsokon IV26 the rulers in Egypt and Syria-Palestine watching the advance of these two foreign powers of Assyria and Kush had to choose which camp they should fall and the majority increasingly came under the Kush’s camp. Piye was succeeded by Shabataqo around 714BC.27

Piye’s Amun temple of Napata viewed from the “holy mountain” of gebel barkal in sudan

The reigns of Shabataqo (714BC-705BC) and Shabaqo (705BC-690BC): Kush in Syria-Palestine, archaism and the image of the ideal Kushite ruler.

Shabataqo ascended to the throne with a fairly complete control of both Egypt and Kush but facing the advance of Assyria to his north east whose army was in 716BC was standing just 120 miles from the city of Tanis in Egypt, Shabataqo thus moved the capital of his empire from Napata to Thebes and crushed the rebellion of Bakenranef in the delta region of Sai who'd succeeded Tefnakht and attempted to assert his independence from Kushite kings, the quelling of this rebellion involved the summoning of Taharaqo (a son of Piye) in 712BC. Shabaqo also extradited Iamani of Ashod to Sargo II of Assyria after the former had rebelled against the latter.28

For now however, Syria-palestine was peripheral to the concerns of Kush and unlike Egypt, wasn't part of the Kushite ideology and royal patrimony, this is reflected in its absence in Kush’s documented history, therefore Assyria's advance to Palestine, the alliances and aid offered by the Kushites and even the battles between its armies and allies in Palestine against Assyria were barely mentioned in Kushite literature, in contrast to the copious amount of documentation that Kushite scribes produced during this time.29 Shabataqo was succeeded by Shabaqo around 705BC.

Shabaqo was heavily engaged in the constriction works and restoration in both Egypt and Kush particularly at Thebes and Napata but the most notable transformation during his rein was the intellectual integration of Kush and Egypt through the identification of his 25th dynasty rulers with the timeless history of Egyptian kingship leading in a process of archaism that is best evidenced by the restoration of the "Memphite theology" whose original copy had been worm eaten when Shabaqo found it, this theology, which presents Memphis as the primeval hill and the original place of creation was salient to Pharaonic kingship.30 Shabaqo also engaged in large-scale building activity in both and Egypt, the erection of statues and carving of reliefs depicting the Kushite rulers. Shabaqo’s archaism which was a revival of concepts and forms of the past and was important to the 25th dynasty King’s ideology but was effected without masking them as traditional Egyptian pharaohs, and their southern origin was iconographicaly emphasized, their royal regalia was distinctly Kushite, enabling them to create their unique image of an idealized Kushite ruler.31

granite heads of Shabaqo with the kushite cap-crown and shabaqo’s restored “memphite theology”

Interlude: war with Assyria and Kush’s rescue of Jerusalem ?

In Syria-palestine, a coalition of Phoenicians, Philistines and the kingdom of Judah had rebelled against Assyria whose emperor Sargon II had died in 705BC and was succeeded by Sennacherib, the latter decided to crush the coalition, which turned to Kush for military aid that Kush honored by sending its armies. Shabaqo’s armies of Kush were led by Taharaqo their commander and the first battle took place at Eltekeh in 701BC and involved Kushite chariots, while the immediate outcome of the battle is disputed by historians but claimed by Assyrians as a victory, Sennacherib went on to divide his army with some besieging Judah’s capital Jerusalem and others taking the rest of the cities, it was this splintered army that Taharqo engaged with, the outcome of which is unknown but the long-term effects were mutually beneficial to all three states involved: Kush, Judah and Assyria, with dynastic continuity in judah (under Hezekiah) and Kush (under Shabaqo and later Taharqo) and the reception of tribute from Syria-palestine that was sent to both Assyria and Kush in the early 7th century BC which points to a kind of settlement between Shabaqo and Sennacherib. This theory is buttressed by the recent discovery of three clay sealings of Shabaqo dated to 700-690 BC in Sennacherib's palace at Nineveh (in Iraq) and another at Megiddo (in Israel)32 which were originally attached to documents (now lost) and one of these seals contains both Assyrian and Kushite seal impressions indicating a two-factor authentication by both seal owners simultaneously (more likely by a Kushite factor in Assyria since Kushite expatriates are mentioned as active at Nineveh in the 8th-6th centuryBC33) attesting to friendly diplomatic relations between Assyria and Kush during the decade immediately succeeding the battle at Eltekeh. This settled outcome has attracted a flurry of publications on Kush's role in the "rescue of Jerusalem" most recently popularized by Henry Aubin’s “The rescue of Jerusalem” and recently supported by group of biblical scholars and Nubiologists one of whom, Jeremy pope, compiled a list of 34 historians that considered Kush either directly or partially responsible for the rescue of judah34. Shabaqo was succeeded by Taharqo in 690BC.

clay seal of shabaqo found in sennacharib’s palace in nineveh (iraq) depiciting the pharaoh sticking a foe as well as a depiction of an Assyrian man before an assyrian god

the reign of Taharqo (690-665BC): the great builder and restorer of temples

Taharqo presided over a relatively long period of prosperity in kushite empire especially in the first two decades of his rule between 690 and 671BC, allowing him to devote himself to major reconstruction and building activity in both his northern and southern realms, and thus becoming one of the "great builders of Egypt"35, his constructions in Kush included temples at Sanam, Napata, Kawa, Tabo, Kerma, Buhen, Gezira, Faras, Qasr Ibrim, and in Egypt he built and reconstructed temples at Philae, Edfu, Mata'na, Luxor, Medinet, Memphis Athribis, Tanis and Karnak (the last of which he is credited individually with the construction and restoration of over a dozen temples)36 while his predecessors had also commissioned construction works, none were to the scale of Taharqo, his building activity was only matched by the Pharaohs of the new kingdom. This monumental building activity couldn't have been possible without the prosperity derived from trade between Kushite empire and Syria-palestine for the luxurious and bulk goods of the latter especially "Asiatic copper" and "true cedar of lebanon" that were important to Kush's economy and royal redistribution system and are explicitly referenced in construction works of which both items were used to build and decorate temples as Montuemhat (a high official under Taharqo's government), wrote in an autobiographical inscription that he, too, had used “true cedar from the best of the Lebanese hillsides”37

Taharqo’s Kawa and Sanam temples (in Sudan), and his “kiosk” and “nilometer” in the Karnak temple complex (in Egypt)

Taharqo in the eastern Mediterranean and the Esarhaddon’s attack of Kush

Syria-Palestine now became part of Kush's political theatre, there was some military action taken by Taharqo in 680's BC in Syria-Palestine and the latter was subject to Kush as a tributary state (now referred in Kush's documents as “Khor”), as mentioned in an inscription by Taharqo at Sanam, this is affirmed by depictions of conquered "Asiatic principalities" in the Sanam temple reliefs38 and the tribute of viticulturists drawn from the nomads of Asia but Khor wasn't central to Kush's politics and Kush’s foreign policy in the region was motivated by long distance trade and border security. In 681BC, the Assyrian King Sennacherib died and was succeeded by his son Esarhaddon, the latter reversed his father's foreign policy, while Sennacherib had destroyed Babylon and chosen to come to settle with Kush, Esarhaddon resolved to restore Babylon and instead advance towards Kush, Esarhaddon begun by systematically advancing through Syria-Palestine culminating in the destruction of Sidon, surrender of Tyre and effective Assyrian control over Palestine and by 673 BC faced off with Taharqa's army but the latter defeated the Assyrian force in what was considered one of Assyria’s worst losses and Esarhaddon retreated to Nineveh. He returned in 671 BC inflicting a defeat on Taharqo's army and the latter retreated to Napata, Esarhaddon appointed the same subordinate chiefs that had served under Taharqo as his vassals, these chiefs switched sides to Taharqo who reappeared in Egypt immediately after Esarhaddon had left. In 667BC, Esarhaddon’s successor Assurbanipal invaded again and the chiefs switched sides, Taharqo retreated south again to Napata, after Esarhaddon left, the chiefs appealed for Taharqo to return but he remained in Napata, and the chiefs were slaughtered by Esarhaddon, Taharqo passed away in 665BC and was succeeded by his son Tanwetamani.

On Tanwetamani ascension, he received the acknowledgement of Amun sanctuaries of Napata and Thebes and went onto affirm his rule in the delta region whose chiefs again welcomed the Kushite king except Necho the Assyrian vassal who was defeated, on receiving this information, Assurbanipal set out for Egypt again, and Tenwetamani, judging his nascent and fragmentary position not strong enough retreated to Napata and the Assyrians sacked Thebes and Psamtik was chosen as the succesor of the slain vassal Necho, while Tanwetamani never reppeared in egypt, the God's wife of Amun elect was still a Kushite princess: Amenirdis II (Taharqo's daughter) who, along with the acting God's wife Shepenwepet II (Piye's daughter) ritually adopted Nitocris (daughter of Psamtik) in 656BC, making the formal end of the Kushite rule in Egypt and with it, the fall of imperial Kush.39 The kingdom of Kush however, went on to outlive Egypt under the Napatan and Meroitic eras (656BC-360AD) and its prosperity is well attested in the cities of Meroe, Musawwarat, Naqa and dozens of others as well as its extensive trade and warfare with Egypt's subsequent colonizers beginning with the Persians, the Ptolemaic Greeks, and the Romans all of whom failed in conquering it with Rome famously signing one of the longest lasting peace treaties with the Kushite queen Amanirenas in the 1st century BC.

Classical literature on Kush’s empire: the view from Greek and biblical scribes

Greek authors on Kush: the ideal ruler and the blameless Aithiopian

In the years after the fall of the 25th dynasty, classical authors begun to collect and write down accounts about the empire of Kush, its rulers and its people. Herodotus (d. 425BC) received his information about Kushite history from Egyptian priests of Ptah temple at Memphis40 while he says that the ethnographic accounts about the people of Kush were collected from other people (in Egypt), Herodotus's accounts of both Egypt and Kush's history are limited by his own curiosities and his perceptions but nevertheless preserve some historical truths, he thus claims that the he was informed of the names of “360 Egyptian monarchs 18 of whom were Kushite" but conflates Shabaqo's reign with the entirety of the 25th dynasty. He praises Shabaqo’s judiciousness and pragmatic nature for sparing the defeated chieftain of the delta and says that Shabaqo ceded power once once a prophesy of an oracle showed him the end of his rule. Herodotus's information of Shabaqo's personality and reign derives from "a combination of the traditional Egyptian image of ideal regency with the image of the ideal Kushite ruler of the Twenty-Fifth dynasty"41, this same image underlines the characterization of the other Kushite/Aithiopian rulers that Herodotus describes such as the Aithiopia ruler who faced off against the Persian King Cambyses, where Herodotus accords moral superiority to Kushite rulers and people over the Persians42, which is in line with his characterization of the idealized Kushite ruler Sabaqos and proves that the source of Kush's positive image in Herodotus' descriptions came directly from the Egyptian priests and their very positive memory of 25th dynasty rule. as Laszlo Torok writes "Egyptian historical memory preserved an ambiguous image of the Kushite dynasty: the Nubian rulers were remembered both as invaders and legitimate kings who reunited Egypt, restored the temples of her gods, and were then overthrown by a cruel conqueror" this heightened nostalgia of Kushite rule heightened under Persian rule as the Egyptians contrasted the “tyrannical” and “godless” Persian conquer with the “benevolent” and “pious” Nubian kings, the priests then conveyed these sentiments to Herodotus who also shared with them a hatred of the Persian ruler Cambyses II (r. 529–522BC) and in Herodotus’ description of the Kushites/Aithiopians he affirmed not just Homer's “pious, blameless and handsome” Aithiopian but complemented it with more realistic accounts about Kush’s history, its rulers and its people at the time of Cambyses II’s conquest of egypt.43 Herodotus’s positive descriptions who then be repeated by later Greek authors Agatharchides of Cnidus (200BC) who i quoted in the introduction and Diodorus Siculus (d. 30BC) the latter of whom spoke highly of the Aithiopians as the first people to worship the gods and the origin of Egyptian civilization44, both of these views originated from Herodotus.

Biblical scribes on Kush and how Aksum became Ethiopia: Kush as a strong and honorable “gentile” nation.

The biblical authors of Isaiah (37:9) and 2 kings (19:9), composed these books the late 6th century and 5th century BC respectively45 the writers explicitly refer to Kush and its ruler as Tirhakah marching out to fight Sennacherib who had besieged Jerusalem, (the chroniclers conflate Taharqo’s generalship and his kingship because Taharqo became king not long after this battle), as mentioned earlier, the documentary evidence from Kush places him at the head of the Kushite army as early as 712BC under Shabataqo and he would have been the leader of the Kushite army that faced off with Sennnacharib. The archival material used by biblical authors to compose these books was likely contemporary with the events described but combined at a later date, and unlike Herodotus, the informants of biblical scribes were local (in Judah itself) and were relating events from their perspective rather than the Egyptian perspective, but they nevertheless thought it necessary to include colorful remarks about a foreign/"gentile” nation (Kush) and its people, this positive portrayal was a result of Kush's military aid to Judah, but was also as a rhetorical tool for religious purposes; after all, the defeat of Sennacharib's siege of Jerusalem is attributed to God striking down his army.46

It was this morally superlative portrayal of Kush/Aithiopia in biblical literature that influenced rulers of the kingdom of Aksum (in modern Ethiopia) to deliberatly appropriate the noun “Aithiopia” as their own self-identification “Ityopyis”/”Ityopya”

which they did for geopolitical and religious purposes; first, with the intent of writing themselves into the grand narratives of classical history where Kush/Aithiopia features prominently and secondly by figuring in the messianic and eschatological role Ethiopia has in the bible primarily the Psalm 68:31 "Envoys shall have arrived from Egypt but Aithiopıa will be the first to extend her hand to God" which positions Ethiopia as the first among the "gentiles" in the sight of God47 and this appears again in Acts 8 with the conversion of the Ethiopian eunuch, which many Christians claim as a “fulfillment of the prophecy” in Psalms, the Aksumite therefore had a strong incentive to consciously self-identify as “Ityopya” which they did beginning in the 4th century and coinciding with Aksum's emperor Ezana's conversion to Christianity in 340AD and Ezana's sack of Meroe in 360AD that formally marked the end of the ancient kingdom of Kush. That the Aksumites were successful in rebranding themselves as Ethiopians (instead of their endonym ‘Habasha’) is reflected in external sources which thereafter referred to Aksumites as Ethiopians beginning with the historian Philostorgius (d. 439AD) and continuing to this present day.48 a product of the legacy of the “strong and powerful” Kushite empire, the “first among the gentiles”.

Conclusion: “Race” and Political paradigms

The ascendance of the 25th dynasty and the formation of the Kushite empire was a momentous event in world history, Kush became the second largest empire and a major global power, reversing centuries of decline and political fragmentation in Egypt and presiding over a period of prosperity by reviving trade with Syria-Palestine, the might of Kush in uniting Egypt and defending Syria-palestine, the benevolence and piety of its rulers in treatment of subordinate chiefs, their devotion to religion, and the character of its people were contrasted with other foreign rulers (and nations) who were often negatively portrayed in Egyptian, Biblical literature and Greek literature in general.49

The positive descriptions of Kushites/Aithiopians (and thus the first unambiguous literary descriptions of black African people in antiquity) was therefore not a general tolerance/openness towards foreign people in classical literature but was instead a direct consequence of the role Kush played in global affairs as the ideal foreign rulers, which was contrasted with the "brutish" foreign ruler such as the Assyrians in biblical literature and the Persians in both Egyptian and Greek literature. What had been Kushite ideologies of governance and border defense inadvertently became the templates for exemplary leadership in the eyes of external observers. Classical writers were infact ambivalent towards foreign people at best and hostile at worst, early Egyptian portrays of Kush were often negative because of the rivalry with Kerma (ie: Kush) which was referred to as "vile kush' or "wretched kush", a stark contrast to the image of Kush that the Egyptian priests were conveying to Herodotus.

However, the conditions that enabled Kush's imperial ascendance to the global political arena couldn't be replicated in the latter centuries as successive empires centered their control in the eastern Mediterranean and northern Egypt, confining Kush to Sudan and southern Egypt despite several incursions into Egypt by the Kushite armies in the later centuries, by the time Kush fell in 360AD, embryonic concepts of race and racism were being formulated in late antiquity between the 1st and 5th century AD, characterized by an increasing the literary focus and commentary on the “curse of Noah” to his grandson Canaan which scholars begun to instead direct at Ham (Canaan’s father) hence the “curse of Ham”, and exclusively identifying Ham with Kush and claiming the curse itself was slavery and blackness. Therefore between Philo in the 1st century AD, the Palestine and Babylonian Talmuds in the 4th century AD, and the medieval Arabic writers in the 10th century, the foundations were laid for later anti-blackness seen in medieval literature and the portrayal of Kush (and thus Africans in general) in negative light. By then, writers were no longer describing African rulers and states that played an active part in their history but peripheral foreigners the majority of whom came not as Kings or military generals but at-best as merchants and at-worst as slaves.50

Proponents of the view that the world of classical antiquity wasn't racist have been criticized by some for “closing their eyes to obvious expressions of anti-black sentiments”, a critique that is blunted when one attempts to define what anti-black sentiment is, while such debates are beyond the scope of this article, the evidence provided here shows that the positive depiction of Kush’s 25th dynasty in classical literature was a direct consequence of the role its rulers and people played in the politics of the societies where those positive sentiments about them were written. And the evidence of the negative descriptions of Kush before its ascendance and after its fall shows how views about “foreign” people were informed by the nature of interactions they have with those writing about them which are dictated by the prevailing political paradigms. The interactions classical writers had with the 25th dynasty and the people of Kush were colored by the political paradigms of the 8th/7th century BC in which Kush was seen as a liberator and its people were remembered as pious, these positive sentiments were then reflected in classical descriptions of Kushites: “the blameless, strong and handsome Aithiopian”.

Read more about the history of Kerma and download free books about the history of Kush on my patreon

Between Two Worlds by László Török pg 87

The Curse of Ham by DM Goldenberg pg 17

The kingdom of kush by László Török pg 69-73)

on how Aksum became Ethiopia; hence the modern country, see “Aksum and Nubia” by George Hatke pg 52-53

Herodotus in Nubia by László Török pg 33,38,49, The Oxford Handbook of Ancient Nubia

by Bruce Williams pgs 702

Jerusalem's Survival, Sennacherib's Departure, and the Kushite Role in 701 BCE by Alice Ogden Bellis pg 41

DM Goldenberg pg 40

The Image of the Ordered World in Ancient Nubian Art by László Török pg 483

The double kingdom under taharqo by Jeremy Pope pg 5

for descriptions of “the foreign” in classical literature see “The Invention of Racism in Classical Antiquity” by Benjamin Isaac

The Oxford Handbook of Ancient Nubia by Bruce Williams pg 184

Between Two Worlds by László Török pg 109)

Between Two Worlds by László Török pg 165-166)

Between Two Worlds by László Török pg 274

The kingdom of kush by László Török pg pg 111-112

The kingdom of kush by László Török pg 121

The kingdom of kush by László Török pg 122

The kingdom of kush by László Török pg 125-126

The kingdom of kush by László Török, pg 147

The double kingdom under tahaqo by Jeremy pope, pg 275-91

The kingdom of kush by László Török, pg 145

Between Two Worlds by László Török. pg 324)

Sudan: ancient kingdoms of the nile by bruce williams, pg 161-71)

The kingdom of kush by László Török, pg 155)

The kingdom of kush by László Török, pg 160)

The Oxford Handbook of Ancient Nubia by Bruce williams, pg 419-420)

(the exact dates of Kush’s reigns are still debated but recent revisions place Shabataqo before the better known Shabaqo and assign the former relatively shorter reign)

sennacherib's departure and the principle of laplace by jeremy pope, pg 119-20, 114)

Beyond the broken reed by Jeremy pope, pg 153-4, 112-117)

The kingdom of kush by László Török, pg 169)

The kingdom of kush by László Török, pg 195)

Sennacherib's Departure and the Principle of Laplace by Jeremy Pope pg 114

The Horses of Kush by LA Heidorn

sennacherib's departure and the principle of laplace by jeremy pope, pgs 100-123)

The Oxford Handbook of Ancient Nubia by Bruce williams pg 421

The kingdom of kush by László Török, pg 141-142),

Beyond the broken reed by Jeremy pope, pg 119

Beyond the broken reed by Jeremy pope, pg 119

The kingdom of kush by László Török 180-188

Herodotus in Nubia by László Török pg 56

Herodotus in Nubia by László Törökpg 79

Herodotus in Nubia by László Török pg 99

Herodotus in Nubia by László Török pg 123-125

the negro in ancient greece by Frank Snowden pg 37

Jerusalem's Survival, Sennacherib's Departure, and the Kushite Role in 701 BCE pg 172

Jerusalem's Survival, Sennacherib's Departure, and the Kushite Role in 701 BCE, pg 22-40

How the Ethiopian Changed His Skin by D Selden pg 339-340

Aksum and nubia by G. Hatke pgs 94-97, 52-53

for racism in antiquity in greco-roman texts, see “the invention of racism in classical antiquity by Benjamin Isaac

for the evolution of anti-black racism in late antiquity to the medieval era, see “The Curse of Ham by David M. Goldenberg pgs 150-156, 160-175”

As a layperson who loves reading about ancient Egypt, and ancient cultures in general, this was great! I feel like many folks are taught history as if different places exist in their own bubbles, but this piece really demonstrates the connection and spread of ideas between these civilizations.

As someone that is Sudanese this touched me. I’ve always knew that Kush had a major impact in the Mediterranean world considering that so many classical writers spoke so highly of Kush. But about racism and the curse of ham in the medieval world. Reading about what medieval Arabs writers wrote about black Africans, a lot of early medieval Arab writers tried to justify their hate for black Africans by using the curse of ham (aka saying that hams descendants were cursed with black skin) and I’ve always just assumed that this was Due to the slave trading of black Africans in the arab world. Cause prior to the 7th century the african states of Axum and kush were spoken of very highly by classical writers and both had a impact on the world, but with the arrival of Islam, you see many medieval writers express there anti black racism by using the curse of ham (al-Jahiz also says that before the advent of Islam, arabs looked up to Axumites/abyssinians and the “Zanj” but after the advent of Islam, arabs began to express more anti-black sentiments). What you wrote about the curse of Ham explains a lot and now, makes a lot more sense to why a lot of early arab writers all of the sudden started using the curse of ham theory (what’s also interesting is that a few Arab writers such as Ibn Khaldun, Al-Jahiz and Ibn al-jawzi all criticise the curse of ham theory and say that it’s not proven). And the Talmuds also explain why Europeans started using the curse of Ham theory as well. This theory clearly has a long legacy concerning certain origins to anti-black sentiments. It was also acknowledged by Ahmed-Baba too, a Timbuktu scholar. But other than that, this article on the kushite impact on the world is fascinating. I feel like Kush doesn’t get the attention it deserves, and I know many that study Kush and Nubia feel the same way. Either way thank you for this wonderful read. It was really eye opening and I am looking forward to other articles you put out in the future.