The Meroitic empire, Queen Amanirenas and the Candaces of Kush: power and gender in an ancient African state

On the enigma of Meroe

The city of Meroe has arguably the most enigmatic history among the societies of the ancient world. The urban settlement emerged in the 10th century BC without any substantial prehistoric occupation of the site, and despite its proximity to the empire of Kush (then the second largest empire of the ancient world), Meroe seems to have remained autonomous, and from it would emerge a new dynasty that overthrew the old royalty of Kush and established one of the world's longest lasting states, as well as the ancient world's least deciphered script (Meroitic), and the ancient world's highest number of female sovereigns with full authority (twelve).1

Despite volumes of documentation written internally in Meroe and externally by its neighbors, all major episodes in its history are shrouded in mystery, from its earliest mention in the 6th to the 4th century BC, it was a scene of violent conflict between the armies of Kush and a number of rebel nomadic groups and it was already serving as one of the capitals of the Napatan state of Kush2, in the 3rd century BC, it was the setting of a very puzzling story about the ascension of a “heretic” king who supposedly killed the priesthood and permanently destroyed their authority3, by the 2nd century BC, it was the sole capital of the Meroitic state, then headed by its first female sovereign Shanakdakheto whose ascension employed unusual iconography and during whose reign the undeciphered Meroitic script was invented under little known circumstances4 and in the 1st century BC, it was from Meroe that one of the world's most famous queens emerged, the Candace Amanirenas, marching at the front of her armies and battling with the mighty legionaries of Rome, her legacy was immortalized in classical literature with the “Alexander Romance” and in the Bible (Acts 8), and it was the city of Meroe that some classical and early modern writers claimed was the origin of civilization.

During the golden age of the Meroitic empire (from late 1st century BC to the early 2nd century AD), 7 of Kush's 13 reigning monarchs were women, two of whom immediately succeeded Amanirenas and altleast 6 of whom reigned with full authority (without a co-regent), an unprecedented phenomena in the ancient world that became one of several unique but enigmatic features of which Meroitic state was to be known : the Candaces of Kush. The title Candace was derived from the meroitic word for sister, and is thus associated with the royal title "sister of the King" a common title for the royal wives (queen consorts) of the reigning monarchs of Kush and Egypt5, by the reign of Amanirenas it was used by Meroitic queen regnants directly after the title Qore (ruler; both male and female) indicating full authority. The peculiar circumstances in which three female sovereigns came to rule the meroitic state in close succession was largely a consequence of the actions of Amanirenas who was in turn building on the precedent set by Shanakdakheto as well as new the ideology of Kingship employed by the Meroitic dynasty of which she was apart.

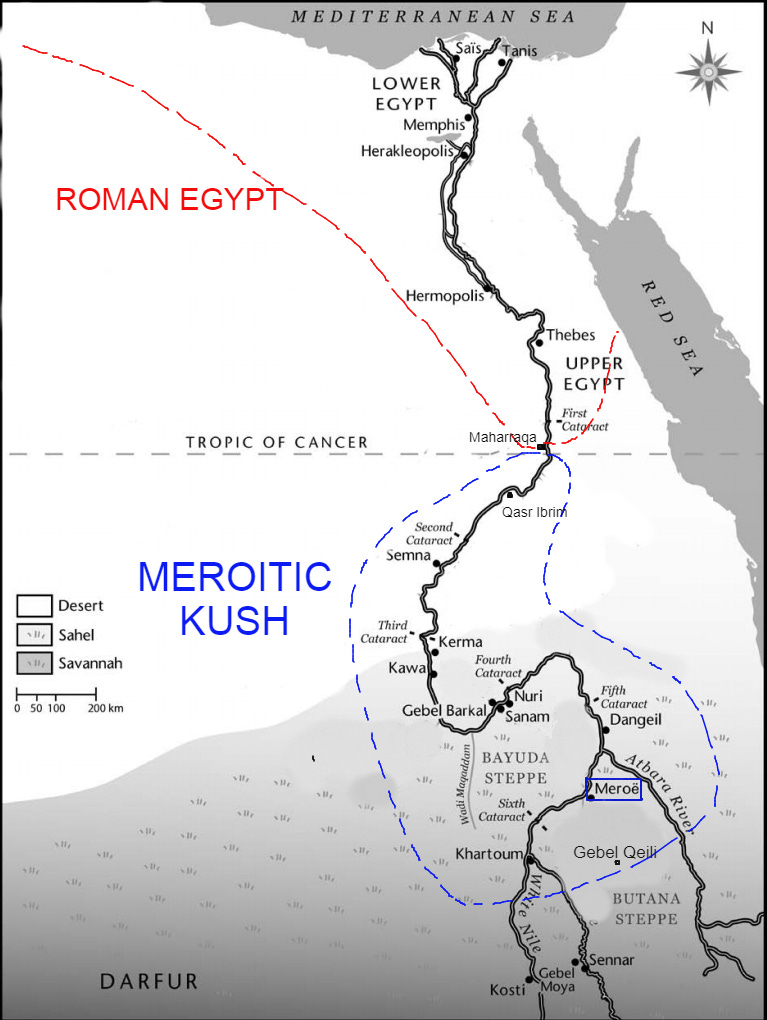

This article provides an overview of the ideology of power of the Meroitic monarchy that enabled the ascendance of famous Candaces of Kush; tracing its faint origin from the Neolithic era through the three successive eras of Kush: the Kerman era (2500BC-1500BC), the Napatan era (800BC-270BC) until their flourishing in the Meroitic era (270BC-360AD), beginning with the appearance of queen Shanakdakheto (mid 2nd century BC) and later with the firm establishment of female dynastic succession under Amanirenas (late 1st century BC) and the actions by which her legitimacy was affirmed including her war with Rome as well as the intellectual and cultural renaissance during and after her reign.

Map of the Meroitic empire during the reign of Queen Amanirenas

Support AfricanHistoryExtra by becoming a member of our Patreon community, subscribe here to read more about African history, download free books, and keep this newsletter free for all:

Origins of female sovereignty in Kush: From the pre-Kerma Neolithic through Queen Katimala to the Napatan-era.

The intellectual and cultural foundations of Kush were laid by the state of Kerma (the first kingdom of Kush), prior to its foundation, the Neolithic cultures from which it emerged possessed a hierarchical structure of power where women occupied the highest position of leadership; the richest grave furnishings from the early Neolithic to pre-Kerma culture (6000BC-3900BC) belong to the burials of women6. (The majority of Neolithic population in the Kerman heartland as well as in the state of Kerma itself, and all its rulers spoke a language called Meroitic, while this confusingly associates it with the city of Meroe, the language was widespread through central and northern Sudan and its speakers originated from the former region around the 4th millennium BC and settled in the latter region to establish the various kingdoms of Kush from Kerma to the Meroitic empire itself7).

While little information about the monarchy of Kerma can be gleaned from the few written sources about it, atleast two of its known rulers were male and the names of their mothers seem to have been closely associated with them8, although there’s little archeological evidence to allow us to understand the position of royal women in Kerma, the exceptional grave of a woman and a child from Dra Abu el-Naga; a royal necropolis near Thebes dating from the 17th dynasty Egypt, contains Kerma material culture which identifies the elite woman as as kerman. The wealth of the burial (which included a gilded coffin and 1/2 pound of jewelry) and its location in a royal necropolis indicates she was part of a diplomatic marriage between Kerma and 17th dynasty Egypt9 and was similar to the Kerman queen Tati’s diplomatic marriage to the contemporaneous 14th dynasty Hyksos rulers.

Coffin of the Kerman queen of the 17th dynasty from the Dra Abu el-Naga necropolis, (Scotland national museum: A.1909.527.1 A)

Kerma fell in 1500BC, after which it territories were controlled by New kingdom Egypt until the 11th century BC when the latter disintegrated enabling the re-emergence of the kingdom of Kush by the 8th century BC, which then advanced onto Egypt beginning with the annexation of the region between the 1st and 2nd cataracts (referred to as "lower Nubia").

In the 10th century BC, lower nubia was ruled by a Queen of Meroitic extract named Katimala (meroitic for "good woman"), she exercised full authority, convened a council of chiefs and reported about her military campaigns in which she led her armies at the front while battling rebels in the gold rich eastern desert, all of which was framed within a strong adherence to the deity Amun. Katimala’s iconography antecedents that which was used by the Napatan queen consorts and Meroitic queen regnants, the queen is shown wearing a vulture crown headdress, facing the goddess Isis (in a role as the goddess of war) and is accompanied by a smaller figure of a princess.

Katimala condemns her male predecessor's inability to secure the polity she now ruled and his lack of faith in Amun, in a usurpation of royal prerogatives, she assumes military and royal authority after claiming that the king couldn't. "Katimala’s tableau may be an appeal to legitimize the assumption of royal office she represents as thrust upon her by the failures of her predecessors and the exigencies of her time"10.

The combination of Katimala's narration of her military exploits, her piety to the deity Amun and the vulture headdress are some of the iconographic devices that would later be used by Meroitic queens to enhance their legitimacy, the commission of the inscription itself antecedents her Napatan and Meroitic era successors’ monumental royal inscriptions and was likely a consequence of the nature of her ascension.

inscription of Queen Katimala at semna in lower Nubia, showing the queen (center) facing the goddess Isis. she is followed by an unnamed princess11

In the 8th century BC, King Alara of Kush (Napatan era) ordinated his sister Pebatma as priestess of the deity Amun and the deity was inturn believed to then grant Kingship to the descendants of Alara's sister in return for their loyalty, his successor Kashta thereafter had his daughter Amenirdis I installed as the "god's wife of Amun elect" at Thebes around 756BC, marking the formal extension of Kush's power over Egypt as the 25th dynasty/Kushite empire. The reigning King's sister, daughter and mother continued to play an important role in the legitimation of the reigning king's authority by functioning as mediators between the deity Amun and the King.12

These royal women were buried in lavishly built and decorated tombs at the royal necropolises of el-kurru/Napata and Nuri along with their kings while others were buried at Meroe. The elevated position of the reigning King's kinswomen to high priestly offices was however not unique to Kush, it was present in Egypt13 and may have been part of Kush’s adoption of Egyptian concepts inorder to legitimize Kush's annexation of Egypt, as part of a wider and deliberate policy of redeploying Egyptian symbols to integrate Egypt into Kush’s realm.14 Included among these “symbols” was the Egyptian script by the Napatan rulers especially King Piye, the successor of Kashta, who composed the longest royal inscription of the ancient Egyptian royal corpus15; the significance of its length connected to Piye's conquest of Egypt and the unification of the kingdom of Egypt and Kush.

Despite the prominent position of the reigning king's kinswomen and the unique way they participated in some royal customs, the kingdom Kush wasn't matrilineal but was bilateral (a combination of patrilineal succession with matrilineal succession) where preference is given to the reigning King's son or brother born of the legitimate Queen mother, the latter of whom was appointed to the priestly office by the reigning king.16 This process greatly reduced succession disputes and explains why there was an unbroken chain of dynastic succession from Alara in the 8th century down Nastasen in the 4th century (the latter tracing his line of decent directly from Alara17), and most likely continued until 270BC when this dynasty was finally overthrown.

statues of the Napatan Queen Amanimalolo of Kush from the 7th century BC, she was the consort of King Senkamanisken (Sudan National Museum)18

Female sovereignty in the Meroitic dynasty: the reformulation of the ideology and iconography of Kingship in Kush.

The emergence of the Meroitic dynasty was related in the story of the cultural hero “Ergamenes, ruler of the Aithiopians” (Greek name for the people of Kush) as told by Agatharchides (d. 145BC), in which he claims that Kush's rulers were appointed by their priests, the latter of whom retained the power to depose the king by ordering him to take his life, this continued until Ergamenes disdained the priest’s authority, slaughtered them and abolished the tradition.

This account, while largely allegorical, contains some truths, but given the Meroitic monarchy's unbroken association of its authority as derived from the deity Amun and the fact that Kush’s priestly class remained firmly under the control of the King in both the Napatan and Meroitic eras rather than the reverse, this story wasn't about the "heretic" nature of Ergamenes but was instead about the deposition of the old dynasty of Kush through a violent coup d'etat.

Ergamenes appears as Arkamaniqo in Kushite sources and took on throne names that were directly borrowed from those of Amasis II -a 26th dynasty Egyptian king who had also usurped the throne, Arkamaniqo then transferred the royal capital from Napata to Meroe as the first King of Kush to be buried in the ancient city thus affirming his southern origins in the Butana region around Meroe city, in contrast to the old dynasty of Kush which was from the Dongola reach around Kerma/Napata city.19

This “Meroitic” dynasty emphasized its own deities: Apedemak, Arensnuphis, and Sebiumeker who had hunter-warrior attributes, which they stressed in a new, tripartie royal costume that represented the ruler as a warrior and hunter, and the iconography of “election” in which Amun and all three deities, divinely "elect" the crown prince as heir to the throne by symbolically touching his shoulder or his crown ribbons.20 The new ideology and iconography of kingship was represented in the monumental temple complex of Musawwarat es sufra, built by the Meroitic kings beginning in the 3rd century and dedicated to these three deities.21

The 64,000 sqm temple complex of Musawwarat es-sufra built by Meroitic King Arnekhamani in the second half of the 3rd century BC dedicated to the deity Apedemak, as well as Arensnuphis, and Sebiumeker.

Coinciding with the ascent of the Meroitic dynasty was a military incursion into lower Nubia by the Ptolemaic rulers of Egypt. lower Nubia was the most important conduit for trade between Kush and the Mediterranean and had since the 3rd millennium BC oscillated between periods of Kushite and Egyptian control usually involving Kush weakening Egypt's control of upper Egypt by supporting rebels of the former or by extending its control over lower Nubia, which was then followed by an Egyptian retaliation to reaffirm its control of parts of the region and was often followed by a period of increased trade and cultural exchanges between the two states.22

In the last iterations of this oscillation, Napatan-era Kush had lost the region to egypt since the withdraw of the 25th dynasty in 655 BC but attempted to extend its control over the region in the 5th and 4th centuries until the 3rd century when the Ptolemies of Egypt annexed the entirety of lower Nubia in 274BC (the whole region from the 1st to the 2nd cataract appears in Greek literature as Triakontaschoinos, while the first half of the region immediately south of the 1st cataract upto the city of Maharraqa was called the Dodekaschoinos).

This annexation occurred just before the ascension of Ergamenes, but Meroitic Kush regained the entire region in 207BC under king Arqamani and his successor, Adikhalamani by supporting local rebels, they also built a number of temples in the region, this lasted until 186BC when the region was again lost to the Ptolemies, only to be regained in 100BC and remain under Meroitic control until the roman invasion of Egypt in 30BC, after which the romans advanced south and took control of the region, intending on conquering Kush itself.23

The temples of Dakka and Dabod built by Kushite Kings; Arqamani and Adikhalamani during Meroe’s two-decade long control of the Triakontaschoinos, because of flooding, they were relocated with the Dabod temple now in spain while the Dakka temple is in Wadi es-Sebua, Egypt24

The war between Rome and Kush: Queen Amanirenas’ two battles and a peace treaty

The Meroitic ruler at the time of Rome's southern march to Kush was Teriteqas who had moved his forces to secure control of lower Nubia that had been rebelling against roman control with Kush's support; the rebels looted the region and pulled down the statues of the roman emperor Augustus sending his severed bronze head to Kush. Teriteqas died along the way and by the time the romans were facing off with Kush's forces, the latter were led by Queen Amanirenas who was accompanied by her son Akinidad.

The outcome of this first battle in 25BC suggests a roman victory which was followed by a roman attempt at conquering all of Kush in 24BC by campaigning in its northern territories was met with disastrous results in a little documented battle between the queen's forces and the romans, this loss forced the romans to withdraw to Qasr Ibrim (near the 2nd cataract) which they then heavily fortified in anticipation of Kush’s advance north following the retreating roman army. The roman forces at Qasr Ibrim were soon faced again with Amanirenas’ army in 22BC, described by Strabo as a large force comprising of thousands of men, its likely the Kushites besieged the fortress as it was only in 21/20BC that the roman emperor Augustus chose to negotiate with them for unknown reasons and signed a peace treaty between Kush and Rome on the island of Samos.

The peace treaty was heavily in favor of Kush and the lower Nubian rebels that it had supported, it included the remission of taxes from the lower Nubians and the withdraw of roman border further north to Maharraqa (ie” rather than controlling the the entire Triakontaschoinos, Rome only controlled the Dodekaschoinos ) the Roman campaign which begun with intent of conquering Kush ended with a peace treaty and the loss of parts of lower Nubia to Kush.25.

The war with Rome and the peace treaty was interpreted as a victory for Kush, the Queen commissioned two monumental inscriptions in the Meroitic script, one of these two inscriptions was about the war with Rome26, and another by her sucessor Queen Amanishakheto depicts a roman captive among Kush’s vanquished enemies27, Amanirenas also commissioned wall paintings in a temple at Meroe (later called the “Augustus temple) that shows a Roman prisoner kneeling infront of her.28 And it was this same queen who received the severed bronze head of Augustus among the war booty from the lower Nubian rebels, which she declined to remit to Augustus during the peace treaty negotiations, she (or her later successor, Queen Amanitore) buried it under the steps of a minor temple at Meroe to symbolically trample over the Roman empire.29

The immediate outcome of the peace treaty was the cultural and intellectual renascence in Kush for nearly two centuries, with heavy investment in monumental building activity, crafts manufacture and arts, an increase in urban population and a proliferation of towns in the Meroitic heartland, as well as the large scale production and distribution of luxury wares all of which was stimulated by the lucrative long-standing trade with their now friendly northern neighbor: Rome.30

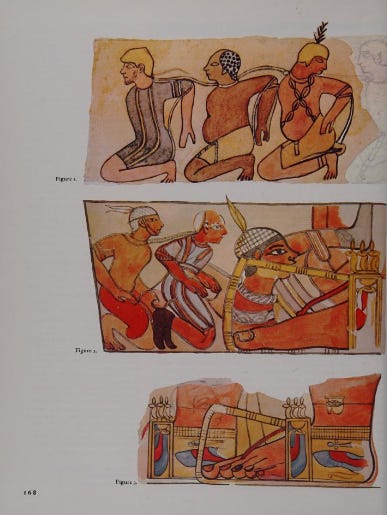

Murals from Queen Amanirenas’ “Augustus temple” at Meroe depicting prisoners bound before the Queen (only shown by her foot and sandals): the first prisoner is a Roman figure wearing a Grecian helmet and stripped tunic, behind him is an African prisoner, an Egyptian figure with a roman helmet and another roman prisoner with the same attire, the second photo also has a roman prisoner at the center without the helmet but with roman-type slippers and tunic. “bound figures” are common in Kushite art and a keen interest is shown in representing different populations/ethnicities through clothing, headresses, hair and skin tone.31

Detail from Queen Amanishakheto’s stela from Naga (REM 1293) showing a bound Roman prisoner with a helmet, tunic and a “European phenotype”, an inscription identifies his ethnonym as “Tameya”: a catch-all term the Kushites used for northern populations that weren’t Egyptian. A stela made by Queen Amanirenas describes the Tameya’s raid directed against an unidentified region; possibly a reference to Kush’s war with Rome or its prelude 32

The “Meroë Head” of Roman emperor Augustus found buried in a temple at Meroe (British museum: 1911,0901.1)

The enigma of Queen Amanirenas’ succession and Akinidad’s princeship, the self-depictions of Kush’s Queens and the invention of the Meroitic script.

Amanirenas was originally the queen consort of King Teriteqas while Akinidad was the viceroy of lower Nubia and general of Kush's armies (one or both of these titles was acquired later), the circumstances by which he was passed over as successor in favor of Amanirenas are uncertain but he remained central in the affirmation of the queens' rule as well as that of her successor; Queen Amanishakheto, who was also originally a consort of Teriteqas. Queen Amanishakheto is thus also shown receiving her royal power (ie: being “elected”) by Akinidad who also accompanies her in performing some royal duties but he is depicted without royal regalia.33

This “election” iconography of a prince crowning the reigning queen was borrowed from Queen Shanakdakheto; in the latter’s case, the unnamed prince is shown conferring royal power to her by touching her crown, and the same iconography was used by Amanishakheto's immediate successor as well; Queen Nawidemak who was “elected” by prince Etaretey34

The queens Shanakdakheto, Amanishakheto and Nawidemak legitimation by the princes, the first two queens are “elected” by the princes (Shanakdakheto’s unnamed prince, Amanishakheto’s prince Akinidad) while Nawidemak is shown receiving mortuary offerings from prince Etretey35

While these four queens were all shown with male attributes of Kingship such as the tripartite costume representing the ideal hunter-warrior attributes of a Meroitic King, as well as images of them smiting enemies, raising their hands in adoration of deities and receiving the atif-crown of Osiris36, their figures were unquestionably feminine, with a disproportionately narrow waist, broad hips and heavy thighs and an overall voluptuous body. More importantly, the royal and elite women of Meroitic kush preferred this self-depiction as the motif is repeated and increasingly emphasized throughout the classic and late Meroitic period (100BC-360AD) 37 This self-depiction by the royal women of Kush was also inline with latter accounts of idealized female royal body in the region of Sudan (and much of Africa) such as James Bruce's account about the King’s wives in the kingdom of Funj38.

This ideal female body depiction in Kush’s art was wholly unlike that of the Egyptian women (of which Kushite art is related) that showed much slimmer figures, nor is it similar to that of the few Egyptian queen regnants (4 out of the 500 pharaohs of Egypt were women) all four of whom are shown to be androgynous with decidedly masculine decorum39, nor is shown by the Egyptian goddesses in Kush’s art such as Isis who retain a slim thin body profile in a way that is dichotomous to the Kushite royal women whom the goddess is paired with but who are shown with much fuller bodies. This iconography begun with Queen Katimala in the 10th century BC and continues to the Naptan era but was greatly emphasized during the Meroitic era. The presence of these voluptuous (and occasionally bare-breasted) female figures in Kushite art since the Neolithic era has been interpreted as associated with fertility and well-being.

Stela and reliefs of the Queens Amanishakheto (first photo, center figure between the goddess Amesemi and the god Apedemak) and Amanitore (last two photos; first one from Wad ban naga, second from Naqa showing her smiting vanquished enemies)

Along with the introduction of new deities, new iconography and new royal customs was the invention of the meroitic script in the late 2nd century BC. The introduction of meroitic writing (both hieroglyphic and cursive) occurred under Queen Shanakdakheto and coincided with her abandonment of the five part titulary (one of the “symbols” from Egypt used by the Napatan dynasty to integrate it into Kush) which was replaced a singular rendering of the royal name in Meroitic, this innovation, added to her new iconography of election was related to her unprecedented ascendance as the first Queen regnant of Kush.40

The cursive meroitic script was used more widely than Egyptian script had been under the Napatan era, this was a direct consequence of the need for wider scope of communication by the Meroitic rulers in a language spoken by the population from which the dynasty itself had emerged, an audience that didn’t include Egyptians and thus obviated the need for continued use of the Egyptian script41.

The copious documentation in cursive meroitic used by Amanirenas also affirmed her legitimacy in a manner similar to Katimala and the length of her inscriptions, both of which narrate her war with Rome as well as donations to temples bring to mind the great inscription of Piye with its focus on military exploits and piety42. The nature of Amanirenas' ascension as well as her successor queen Amanishaketo over the would-be crown-prince Akinidad as well as the shifts in burial ground during this time alludes to some sort of dynastic troubles that ultimately favored both these consorts to assume authority of the kingdom in close succession and with full authority.43

Amanirenas’ assumption of command over Kush's armies and her appearance at the head of the armies in the all battles with Rome served to affirm her leadership in the image of an ideal Kushite ruler (as well as act as evidence for her divine favor), she was therefore similar to Katimala leading her armies form the front44, as well as Piye and Taharqo both of whom famously led their armies from the front45.

Monumental inscription of Queen Amanirenas depicted in a two-part worship scene: on the left she is shown in the center wearing sandals with large buckles, the figure standing behind her is the bare-footed prince Akinidad, both face the deity Amun, the image is reverse on the right where they face the goddess Mut. (British museum photo)

Queen Amanitore, and King Natakamani’s temples of Apedemak, Hathor and Amun. the pylons of the Apedemak temple (at the extreme left) show both rulers smiting their enemies

Conclusion: On gendered power in Ancient and medieval Africa’s highest position of leadership; the case of Amanirenas, Queen Njinga, the Iyoba of Benin, Magajiya of Kano and elite women in Kongo.

Amanirenas ruled the Meroitic empire of Kush at a pivotal time in its history when the kingdom's existence was threatened by a powerful and hostile northern neighbor, her ascent to Kush's throne in the midst of battle, the favorable peace treaty she signed with Augustus, the intellectual and cultural renaissance she heralded establishes her among the most powerful rulers of Kush. The enigmatic nature of her enthronement doubtlessly set a direct precedent for her immediate successors and was part of the evolving changes in the concepts supporting royal legitimacy in Meroitic Kush which enabled the rule of female sovereigns with full authority, the “election” of these Queens was initially legitimized by princes and in a few instances they ruled jointly with their husbands (although both reigned with full authority) but by the time of the reigns of the later Queens of the 2nd-4th century, this legitimizing prince figure was removed and the regency of Queens was was now interpreted in its own terms46.

The ascendance of women to the throne of Kush was therefore contingent on the ideology of Kingship/Queenship brought by the Meroitic dynasty, this stands in contrast with the earlier periods of Kush's history and the medieval kingdoms of Nubia and Funj where kingship was strictly male, and it also stands in opposition to the common misconception about female sovereigns in Africa being determined by matrilineal succession or ethnicity because Kush was bilateral and was dominated by Meroitic speakers for all its history.

Queenship in Africa was instead determined by ideology of the monarchy in a given state; this is strikingly paralleled in the west-central African kingdom of Ndongo&Matamba where Queen Njinga (r. 1583-1663AD) had to quash doubts about the legitimacy of her rule which had been challenged based on her gender and her ability to rule, she countered this by initially acting as a regent for the crown prince, but later assuming full authority of the Kingdoms, she then took on attributes associated with Kings and engaged in "virile pursuits" such as her famous wars with the Portuguese that resulted in the successful defeat of their incursions into her kingdom. Her momentous reign set an immediate precedent for her female successors who didn't face challenges to their rule based on their gender and needed not assume male attributes to affirm their legitimacy thus making Njinga’s Guterres dynasty the second in African history with the highest number of female sovereigns.47

This is also similar to the creation of the powerful queen mother office in the kingdom of Benin due to the actions of Idia the mother of Oba Esigie (r. 1504 –1550)who led armies into battle to secure her son's ascension and directly led to the creation of the Iyoba office which was occupied by the Oba’s kinswoman and was as powerful as the offices of the town chiefs who were directly below the Oba (king) and were all male48, a similar situation can be seen from the actions of the Queen mothers of Kano with the establishment of the Maidaki and Magajiya office after the political performance of Hauwa and Lamis in the reigns of Abdullahi (1499-1509) and Kisoke (r. 1509-1565)49, and in Kongo, where elite women rose to very influential offices of the state’s electoral council effectively becoming Kingmakers during the upheavals of the dynastic struggles in the Kingdom between 1568 and 1665AD 50 although neither Benin, nor Kano nor Kongo produced Queen regnants.

The issue of Female sovereignty in Africa is a complex one that goes beyond the reductive clichés about gender and power in precolonial Africa, the actions of Amanirenas and Njinga allow us to understand the dynamics of pre-colonial African conceptions of gendered authority which were in constant flux; enabling the rise of Queen regnants to what had been a largely male office of King, and successfully leading to the establishment of dynasties with a high number of Women rulers in a pattern similar to female sovereignty in Eurasia51.

Amanirenas' legacy looms large in the history of Africa's successful military strategists, but her other overlooked accomplishment is the legacy of the Candaces of Kush; their valour, piety and opulence appears in classical literature with an air of mystique, much like the enigma of Meroe.

pyramid tombs of queen Amanitore and Queen Amanishakheto at Meroe

Read more about the history of Kerma and download free books about the history of Kush on my patreon

The Kingdom of Kush by László Török pg 204-206).

The double kingdom under Taharqo by J.Pope, pg 33 and The kingdom of kush by L. Torok pg 367-70, 379,380

The kingdom of kush by L.Torok pg 420-23

The kingdom of kush by L. Torok pg 211-12, 443-444, The Image of the Ordered World in Ancient Nubian Art by L. Torok pg 261, 451-456

The kingdom of kush by L Torok pg 214)

Between two world by L. Torok pg 26-29)

The meroitic language and writing system by Claude Rilly pg 177-178

The oxford handbook of ancient nubia pg pg 185

The Political Situation in Egypt During the Second Intermediate Period pg 180,Gilded Flesh pg 45

The inscription of queen katimala by John Coleman Darnell pg 7-63

The inscription of queen katimala by John Coleman Darnell pg 7-12

The kingdom of kush by L.Torok pg 234-241)

Dancing for hathor by Carolyn Graves-Brown pg 48)

Sudan: ancient kingdoms of the nile by bruce williams, pg 161-71)

The Kingdom of Kush pg 162

The Kingdom of Kush, pgs 255-261 and Royal sisters and royal legitmization in the nubian period by roberto gozzoli pgs 483-492

The kingdom of kush by L Torok pg 57)

The Image of the Ordered World in Ancient Nubian Art by L. Torok pg 303

Hellenising art in ancient nubia by L. Torok pg 13-18)

Hellenising art in ancient nubia by L. Torok pg 209-213)

Image of the ordered world by L Torok, pg 177)

The kingdom of kush László Török pg 424-425

Between Two Worlds by László Török pg 377-434)

Between Two Worlds by László Török pg 393

The kingdom of kush by L. Torok pg 451-455)

The kingdom of kush by L. Torok pg 456-457)

Les interprétations historiques des stèles méroïtiques d’Akinidad à la lumière des récentes découvertes Claude Rilly

Between Two Worlds by László Török pg 455-456

Headhunting on the Roman Frontier by Uroš Matić pg 128-9

The kingdom of Kush pg 463-466

Studies in ancient Egypt, the Aegean, and the Sudan by Charles C. Van Siclen pgs 167-171

photo from “Les interprétations historiques des stèles méroïtiques d’Akinidad à la lumière des récentes découvertes by Claude Rilly”

The image of ordered world in ancient nubian Art by Laszlo Torok pg 217-219)

The kingdom of kush by L. Torok pg 455-458, 443-444)

Fontes Historiae Nubiorum vol 3, pg 803

The kingdom of kush pg 460, The oxford handbook of ancient nubia pg 1022

The oxford handbook of ancient nubia pg 10026, 638-639)

An Interesting Narrative of the Travels of James Bruce, Esq., Into Abyssinia by james bruce pg 368-369

Dancing for hathor by Carolyn Graves-Brown pg 129)

The kingdom of kush pg 212)

Image of the ordered world in ancient nubian art pg 455)

the kingdom of kush pg 161-163

The kingdom of kush pg 460-61

The inscription of queen Katimala pg 30)

The kingdom of kush pg 159

The kingdom of kush pg 469)

Legitmacy and political power queen njinga by J.K.Thornton pg 37-40)

Royal Art of Benin by Kate Ezra pg 14

the government in kano by M.G.Smith pg 136, 142-143

Elite Women in the Kingdom of Kongo by J.K.Thornton pg 437-460

The Rise of Female Kings in Europe, 1300-1800 By William Monter