The Nsibidi script ca. 600-1909 CE: a history of an African writing system

Nsibidi is one of Africa's oldest independently invented writing systems. It's a semasiographic script comprised of ideograms and pictograms that were used in southeastern Nigeria among the Ejagham, Efik, Igbo, and Ibibio societies.

Nsibidi records, transmits, and conceals various kinds of information using a fluid vocabulary of geometric and naturalistic signs depicted on a wide range of mediums; from pottery dated to the 6th-11th century; to manuscripts; textiles; and inscribed artwork from the 19th century.

The formal world of Nsibidi writing encompassed both simple and complex signs of communication that expressed abstract ideas which carried functional, aesthetic, and esoteric meanings for its users.

This article outlines the history of Nsibidi from the earliest archeological evidence for its invention in the mid-first millennium CE to its development in the 19th century across multiple societies from Nigeria to Cuba.

Late 19th century Brass tray from Calabar, Nigeria depicting a local mermaid figure surrounded by numerous Nsibidi pictograms. now at the Pitt Rivers Museum.

Support African History Extra by becoming a member of our Patreon community, subscribe here to read more on African history and to keep this blog free for all:

The ethnography of Nsibidi: societies of south-eastern Nigeria.

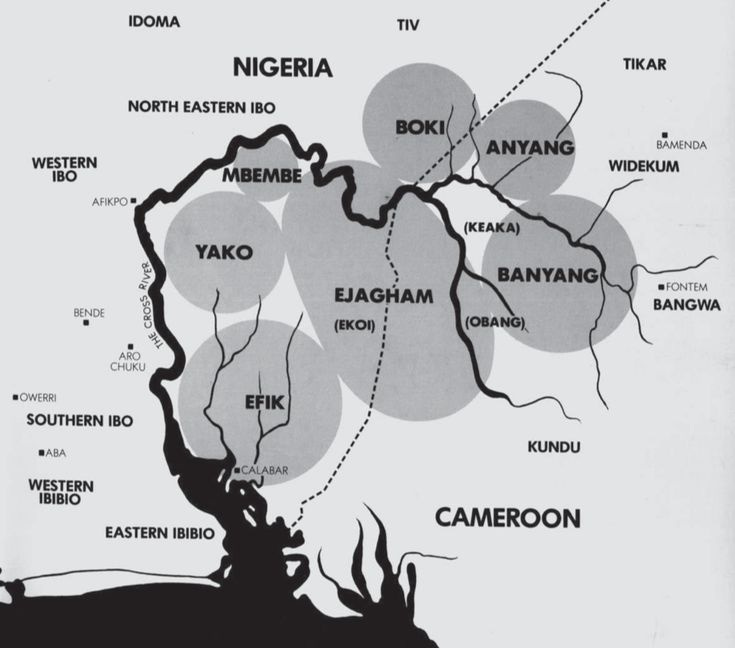

map of the cross-river region on the Nigeria-Cameroon border showing the ethnic groups mentioned in this article who use Nsibidi.

Archeological findings and historical traditions from south-eastern Nigeria's “cross-river” region indicate that the symbolic reservoir from which Nsibidi derived its glyphs was not the product of a single social group, but of many societies. While the Ekpe (Leopard Society) of the Efik people has been the most prominent institution associated with Nsibidi since the early 20th century when the script was first studied, it is not the only one, but most likely superseded the other societies fairly recently.

Traditions of the Ejagham people of south-eastern Nigeria mention the existence of an Nsibidi (or Nchibbidi) Society, which predated the Efik's Ekpe society. A king of Oban in southern Ejagham relates that nsibidi was taught to them by water deities ( mermaids) and that it emerged in the dreams of certain men who thus received its secrets and later presented them to the outside.1

According to the pioneering study of the script by the anthropologist P.A. Talbot, its name was derived from the Ejagham word nchibbi, which he defined as “to turn’, and this has taken to itself the meaning of agility of mind, and therefore of cunning or double meaning”. He adds that it is possible that the Nsibidi writing was developed among the members of the Ejagham’s Ekoi society “as a method of communication or, perhaps with greater likelihood, its use was kept up by them long after it had been forgotten outside their circle”2

Other groups in the cross-rivers region that are now known for writing in Nsibidi include the Bende subgroup of the Igbo speakers; the Ekeya clan of the Okobo subgroup of the Ibibio speakers;3 and the the Ekois who live along the Nigeria-Cameroon border. Nsibidi is therefore common to various populations of the Cross River region in south-eastern Nigeria, through centuries of successive borrowings and exchanges with other societies.4

The main users of the Nsibidi are individuals of the Ekpe (or "leopard men") institution which allows social regularization within the Efik group. Composed of an elitist group of male individuals, the esoteric institution imposed the socio-economic rules of the Calabar Region. Through their use of nsibidi, the Ekpe institution gave its signs a strong social and political function by concealing the meaning of certain signs to its affiliates but displaying them in public to show the power of Ekpe.5

While the secret societies were primarily Male fraternal groups, Women were closely associated with the use —and perhaps the invention— of the Nsibidi symbols. The meeting places of women from both the Ejagham and Efik groups were centers for the arts, where women were taught the art of Nsibidi writing, often by other women. Ekpe societies north of the Cross River also encouraged more participation of women in its affairs, indicating that their role in the secret society varied greatly.6

As noted by the British consul Hutchinson while he was in Old Calabar during the 1850s, “the women of Old Kalabar are not only the surgical operators, but are also artists in other matters. Carving hieroglyphs on large dish calabashes and on the seats of stools; painting figures of poeticized animals on the walls of the houses; weaving and dyeing mats, —all are done by them.” 7

According to the art historian R. F. Thompson: “it was the Ejagham female who was traditionally considered the original bearer of civilizing gifts. Ejagham women also engaged in plays and artistic matters. Their “fatting-houses” (nkim) were centers for the arts, where women were taught, by tutors of their own sex, body-painting, coiʃure, singing, dancing, ordinary and ceremonial cooking, and, especially, the art of nsibidi writing in several media, including pyrogravure and appliqué.”8

The various mediums of writing on which Nsibidi symbols are preserved, such as calabashes, wall paintings, and dyed mats/cloths were primarily made by women.

The archeology of Nsibidi: Calabar pottery with proto-Nsibidi glyphs from 6th-14th century CE

The precursors of Nsibidi symbols are attested across the archeological record of Calabar, with the earliest traces of proto-Nsibidi picto-ideograms appearing on pottery dated to the 6th-9th century CE.9

Many of the ceramics found in this region, such as bowls, anthropomorphic vessels, and figurines, are decorated with combinations of carefully rendered geometric designs consisting of similar “families” of patterns that show up repeatedly. These include concentric circles, spirals, arcs, chevrons, lozenges, crosses, stars, grids, and interlaces, which are all motifs that are prominent in later Nsibidi writing.10

While the overall designs often consist of variations of similar motifs, the makers of the ceramics displayed an obvious preference for creating unique works rather than multiple duplicates and maintained a fairly consistent style of impressed decoration. The symbolic function of these Calabar ceramics especially as grave goods and shrine furnishings as well as their elaborate decoration with familiar patterns of symbols and distinctive motifs, is directed related to historical practices and symbolism associated with Nsibidi writing and related artwork.11

Anthropomorphic vessel from the Okang Mbang site, Calabar, ca. 11th-14th century, NCMM Nigeria. The vessel is decorated with a complex cruciform design with 8 corners. images by Christopher Slogar.

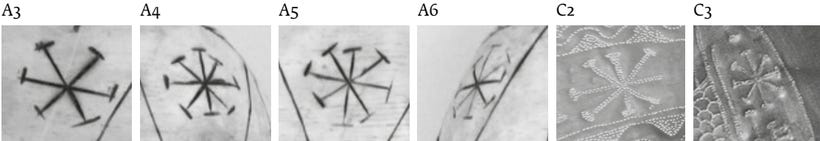

Cruciform designs inscribed with Nsibidi glyphs, taken from a brass tray and wooden crest at the Pitt Rivers Museum. collected ca. 1914-1919. Images by Morgane Pierson.

(L-R) Underside view of a bowl fragment showing the base, Obot Okoho site; Detached base from a bowl, Obot Okoho site; Profile and underside views of a bowl, Okang Mbang site. Calabar, ca. 11-14th century NCMM Nigeria. images by Christopher Slogar.

Nsibidi arc signs on the brass dish and wooden crest at the Pitt rivers museum. these arcs generally represent a person doing various activities. Images by Morgane Pierson.

Wooden crest mask in the form of a bird's head and beak, inscribed with Nsibidi writing. Ejagham artist, Collected between 1904-1914, Pitt Rivers Museum.

Brass dish made locally from a recycled sheet of brass salvaged from a shipwreck. Efik artist. collected between 1915 and 1919 from Old Calabar, Nigeria, for the Pitt Rivers Museum, U.K.12

The dish is decorated with hammered designs and depicts a mermaid in the center with a forked scaly tail and wearing a crown, encircled by nsibidi symbols. The mermaid is adorned with intricate body-painting or wears an elaborate long-sleeved bodice decorated with geometric patterns. She holds a comb in her right hand and a mirror in her left hand. In the space above her right shoulder there is a bottle and a glass on a table, and above her left shoulder there is what appears to be a flower in a pot or vase. She is accompanied by a fish and a lizard.

Drawing of the brass dish highlighting the Nsibidi symbols. image by Morgane Pierson

The rim of the dish is divided into eight sections, four decorated with images of birds on foliage, the four longer ones with other nsibidi pictograms. The Nsibidi symbol next to the mermaid’s left fishtail that is in the form of a ball with the feathers on top (C10) represents the Nkanda calabash. Nkanda is the highest class in Ekpe society to which all Ekik men aspired. The oval with a double outline and several circles inside (located on the C11 rim and in the C12 inner circle), represents the primordial sign of the Nsibidi corpus and is found in many media in association with Ekpe rituals.13

There is a similar object at the Glasgow Museum that depicts fish leopards with checkerboard skin next to a mermaid with a chewing stick. The appearance of mermaids on brass dishes with Nsibidi writings corroborates the traditions associating the script with supernatural aquatic metamorphoses.14

Objects with Nsibidi inscriptions are not simply decorative items, but mediums in which powerful forces can be perceived by those with the necessary cultural knowledge.

Calabash with Nsibidi inscriptions, ca. 1910, Calabar, Nigeria. British Museum

an elaborately decorated bowl from the Old Marian Road site, ca. 6th-8th century, Calabar, NCMM Nigeria. Anthropomorphic vessel from Okang Mbang site. ca. 11th-14th century, Calabar, NCMM Nigeria. images by Christopher Slogar.

The archeological findings outlined above point to the significance of the city of Old Calabar in the development of the Nsibidi writing system. The cosmopolitan city is home to three major ethnic groups—the Efik, Qua, and Efut—who are in turn each closely related to other groups located throughout the basin, from the Ibibio and Oron in the south to the Ejagham in the north. However, the pottery presented here predates the arrival/formation of these groups, who don’t claim to be autochthonous to the region, despite utilizing the Nsibidi script in the later periods. Nevertheless, the Calabar archaeological material presents an important opportunity to consider the possible ancient roots of the widely used communication system called nsibidi.15

Fragment of a decorated bowl with proto-Nsibidi glyphs, Okang Mbang site. Near Calabar, Nigeria. ca. 11th–14th century. NCMM Nigeria. image by Christopher Slogar

Deciphering the Nsibidi writing system.

Nsibidi at the time of its discovery was likely undergoing a process of standardization.

Its semasiographic (or; pictorial) characters denote meaning and logic like the Maya glyphs and other Mesoamerican writing systems, rather than the more common glottographic scripts which denote the exact notation of sound and speech such as the Arabic and Latin scripts. That is to say that while the letters used in the alphabetic scripts only have meaning through correlation with another letter, the pictograms only refer to a single object that they represent.16

Nsibidi is a fluid system containing more than 1,000 signs that can be divided between the basic glyphs including pictographic signs (such as; a manilla, leopard and mirror) and abstract signs (such as; an arc, cross, grid, circle, and spiral). The signs can be traced with the finger, tinted, carved into the wood, hammered into metal, and the diversity of mediums explains why the length of the lines, their width or their orientation are adjustable.17

Nsibidi primarily represents communication on several hierarchies. The same sign can have multiple interpretations, and thus context plays an essential differentiating role.

First, there were signs most people knew, regardless of initiation or of rank in a given secret society, signs representing human relationships, communication, and household objects.18 For example, an arc symbol in Nsibidi generally indicates a person, so a combination of arcs describes different sorts of personal relationships and activities. Hence, the sign of two intertwined arcs signifies conjunction, love, or marriage.19

Nsibidi glyphs and their approximate translations

Other symbols such as double gongs and feathers are attributes of leadership, and manillas represent currency, while signs circumscribing radial accents indicate the complexity of initiation into the secret societies. Some of the symbols are purely abstract and refer to a given secret society's ideology. For example, The “dark signs,” were symbols of danger and extremity in the Abakuá society of Afro-Cubans mentioned below.20

Small repeating triangles refer to the leopard’s claws and therefore signify the group’s power, while concentric rectangles may refer to the society meeting house.21

The fluidity of Nsibidi writing made it a very economical writing system compared to alphabetical scripts. This can be demonstrated by the translation of a trial proceeding shown below, which utilized just 14 blocks of Nsibidi signs compared to the over 158 words, or 800 signs required for its English/French translation.22

According to the linguist Simon Battestini, it seems that some signs correspond to lexemes, that is to say a unit of meaning and sound fixed in a language (for example in French, the words ‘mangent’ and ‘mangeront’ are forms of the same lexeme "manger"). While others would only be read with the help of more or less numerous groups of signs corresponding to our noun phrases, as a more or less complex thought group.

This textual organization is characterized in reading first of all by a preliminary search for the main blocks of meaning and then a detailed reading according to the logical succession of ideas. This is where the differences in size of certain glyphs can be important as the variations in scale between the glyphs allow the reader to identify, even before starting an in-depth reading, the context of certain important words and/or sentences.23

Corpus of Nsibidi signs and symbols. image by Elphinstone Dayrell, 1911

Mediums for representing Nsibidi writing.

Nsibidi Cloth and wood:

The ukara cloth is among the more prominent examples of Nsibidi used by groups such as the Leopard society on formal occasions. The composition of ukara is usually in the form of a grid that makes a wrapper, with each section containing a symbol in white set against an indigo background. The symbols depicted include images of Leopard Society masquerades and powerful creatures associated with the group, such as the leopards and crocodiles, as well as easily recognizable symbols like Arcs, arrows, circles, and crosses, which are often in combination.24

20th century, Ukara cotton cloth of the Ekpe society with Nsibidi symbols, Brooklyn museum

20th century, ukara cloth of the ekpe society with Nsibidi symbols, Houston museum of fine arts

Nsibidi Wooden Fans.

Ritual fans bearing pyrograved Nsibidi called effrigi, were used in contexts involving initiation into secret societies. These signs are often neatly rendered with the heated end of a metal.25

Igbo or ibibo fan dated to 1859, Now at the national Museums Scotland

Cross River/Ejagham, Effrigi ritual initiation fan displaying Nsibidi signs, NCMM Nigeria, dated 1950.

Nsibidi Manuscripts;

While Nsibidi signs in south-eastern Nigeria weren't written on paper until the early 20th century, descendants of enslaved people who carried the knowledge Nsibidi and Ekpe society rites to the Island of Cuba, utilized paper to render its glyphs in writing.

Nsibidi signs emerged in Cuba as early as 1812, used by a free black militia leader jose Antonio Aponte, whose manuscripts were seized after his arrest. Another incident in 1839 resulted in the confiscation of Nsibidi manuscripts from Margarito Blanco, a black dock worker whose premises had been raided by the Havana police. These manuscripts were emblazoned with Nsibidi ideographs and signatures of high-ranking priests of the "Abakuá" secret society which is largely derived from the Ekpe society.26

Nsibidi Manuscript written in 1877 by an Abakua society member in Cuba, private collection. It’s about a written declaration of war between Efik rulers of Calabar

19th century Nsibidi Manuscript written by an Abakua member in Cuba, private collection.

Nsibidi wall inscriptions and Body tattoos

Painted Nsibidi patterns decorated Leopard Society meeting houses and homes of Leopard Society members. A description by Tomas Hutchinson, who was in Old Calabar in the 1850s, provides one of the earliest descriptions of Nsibidi wall inscriptions inside the house of Efik trader and leopard society member Antika Cobham ;

“Whilst seated on one of these (Sofas) my eyes wandered over the place. The walls all round the court are adorned with a variety of extravagant designs of apocryphal animals; impossible crocodiles, possessing a flexibility in their outlines as is never seen in the living specimens; leopards with six feet; birds with horns from their tails. Diamond, and crescent, and cruciform shapes of varicolored hues abound wherever there is a spot to paint them on”27

Depiction of Nsibidi inscriptions on the walls of an Igbo hut by P. A Talbot in 1917

Nsibidi Tattoos:

Leopard Society members paint their bodies with Nsibidi glyphs in preparation for important occasions. They decorate their bodies with Nsibidi for other transitional events, such as the initiations and funerals of fellow members and the installation of new paramount rulers, who are often chosen from the ranks of Leopard Society members, especially in Calabar.28

Nsibidi body tattoos and Ukara cloth with Nsibidi glyphs, both shown in a procession of Ekpe Leopard Society members of the igbo group; during the burial of an initiate in Arondizuogu town 1988, and in Arochukwu region in 1989

Nsibidi Esotericism: Secret societies in south-eastern Nigeria

Knowledge of some Nsibidi signs may be restricted to members of certain groups. For example, members of the pan-regional Leopard Society are proscribed from discussing with outsiders the full meanings of particular Nsibidi signs.29

The oldest among the secret societies associated with Nsibidi were the Nnimm society of women among the Ejagham people. This society is said to have received the signs from mythical beings ( water deities/mermaids) and shared them with the Ngbe (leopard) society of Ejagham men. From the Ejagham, the knowledge of Nsibidi was spread to the Efut people, who adapted and disseminated Ejagham art and culture and sold its secrets to the Efik of Calabar around the mid-18th century, the latter of whom renamed it Ekpe.30

In Calabar, Nsibidi is generally associated with the Efik men’s Leopard Societies which wielded great legislative, judicial, and executive power In the precolonial era. The power of the Leopard Societies was maintained in part through the esoteric use of Nsibidi, which members learned more deeply as they advanced in rank within the society.31

According to historians and anthropologists Ivor Miller and Matthew Ojong, ekpe played four major roles in pre-colonial life. First, it was the institution that granted or denied citizenship status and thus the right to make important decisions in society. It also represented executive authority and therefore the power of punishment. For example, if a member disobeyed the law, the institution could choose to confiscate his property. Ekpe members also took care of entertainment such as dancing, music or organizing masquerades. Finally, the ekpe institution was an esoteric school where members gave teachings on the meaning of life and the cyclical process of regeneration and therefore reincarnation of the being.32

A transcript of a court proceeding written in Nsibidi inscriptions was preserved by one of the Ekpe members, copied and translated for the missionary J.K Macgregor who was active in Calabar during the early 20th century and wrote a monograph on the Nsibidi script in 1909.33

His translations are now used in the process of deciphering the script.

Nsibidi glyphs and their translation by J.K Macgregor.

By their use of the Nsibidi, the Ekpe society gave the script a strong social and political function, and while some signs are only known to its members, the uninitiated recognized them as the insignia of the institution and respected the people or places that were covered with them.34

As noted by J.K Macgregor : “A wide-spread use is to give public notice or private warning of anything,-to forbid people to go on a certain road, an nsibidi sign, far more powerful than any constable, is made on the ground: to warn a friend that he is to be seized, the sign of a rope is chalked where he cannot fail to see it, and he at once flees: to convey the wishes of a chief to all who may come to visit him, signs are set on the walls of his house.”35

Conclusion: the Nsibidi script as a new frontier in studies of Africa’s intellectual history.

While the Nsibidi writing system has recently attracted significant scholarly interest as one of Africa's oldest independently invented scripts, the script remains poorly understood and is only partially deciphered, partly because of the secrecy surrounding pictorial-ideograms, and its contextual form of interpretation.

The discovery of old ceramics with proto-Nsibidi glyphs in the Calabar region, and recent studies of manuscripts written by Afro-Cubans who originated from south-eastern Nigeria have pushed back the age of the Nsibidi script, revealing a rich African intellectual heritage whose significance has only begun to be appreciated.

The above essay on the Nsibidi script was first posted on Patreon,

My latest Patreon article explores the function of West Africa’s rural castles and fortress-houses that were recently elevated to UNESCO World Heritage status, and the history of the communities which built them.

Please subscribe to read about it here:

Flash of the Spirit: African and Afro-American Art and Philosophy by Robert Farris Thompson pg 298, Compass - Comparative Literature in Africa edited by Maduka, Chidi T., Ekpo, Denis, pg 229

Early Ceramics from Calabar, Nigeria Towards a History of Nsibidi by Christopher Slogar pg 21

Flash of the Spirit: African and Afro-American Art and Philosophy by Robert Farris Thompson pg 301

Étude typographique du système d’écriture nsibidi, des pictos-idéogrammes du Nigeria by Morgane Pierson pg 7

Étude typographique du système d’écriture nsibidi, des pictos-idéogrammes du Nigeria by Morgane Pierson 11

Flash of the Spirit: African and Afro-American Art and Philosophy by Robert Farris Thompson pg 280, Étude typographique du système d’écriture nsibidi, des pictos-idéogrammes du Nigeria by Morgane Pierson pg 13

Impressions of western Africa, 1858: With Remarks on the Diseases of the Climate and a Report on the Peculiarities of Trade Up the Rivers in the Bight of Biafra, by T.J Hutchinson, pg 160

Flash of the Spirit: African & Afro-American Art & Philosophy by Robert Farris Thompson pg 230

Early Ceramics from Calabar, Nigeria Towards a History of Nsibidi by Christopher Slogar pg 23, Étude typographique du système d’écriture nsibidi, des pictos-idéogrammes du Nigeria by Morgane Pierson pg 7

Early Ceramics from Calabar, Nigeria Towards a History of Nsibidi by Christopher Slogar pg 23)

Early Ceramics from Calabar, Nigeria Towards a History of Nsibidi by Christopher Slogar pg 24

Étude typographique du système d’écriture nsibidi, des pictos-idéogrammes du Nigeria by Morgane Pierson 29-31

Étude typographique du système d’écriture nsibidi, des pictos-idéogrammes du Nigeria by Morgane Pierson 31.

Compass - Comparative Literature in Africa edited by Maduka, Chidi T., Ekpo, Denis 229-230,

Early Ceramics from Calabar, Nigeria Towards a History of Nsibidi by Christopher Slogar pg 28

Étude typographique du système d’écriture nsibidi, des pictos-idéogrammes du Nigeria by Morgane Pierson pg 19

Étude typographique du système d’écriture nsibidi, des pictos-idéogrammes du Nigeria by Morgane Pierson pg 21

Flash of the Spirit: African and Afro-American Art and Philosophy by Robert Farris Thompson pg 299)

Early Ceramics from Calabar, Nigeria Towards a History of Nsibidi by Christopher Slogar pg 19)

Flash of the Spirit: African and Afro-American Art and Philosophy by Robert Farris Thompson pg 300-302

Early Ceramics from Calabar, Nigeria Towards a History of Nsibidi by Christopher Slogar pg 20)

Étude typographique du système d’écriture nsibidi, des pictos-idéogrammes du Nigeria by Morgane Pierson pg 23

Étude typographique du système d’écriture nsibidi, des pictos-idéogrammes du Nigeria by Morgane Pierson pg 23

Early Ceramics from Calabar, Nigeria Towards a History of Nsibidi by Christopher Slogar pg 20)

Flash of the Spirit: African and Afro-American Art and Philosophy by Robert Farris Thompson pg 300)

The Relationship between Early Forms of Literacy in Old Calabar and Inherited Manuscripts of the Cuban Abakuá Society by Ivor L. Miller pg 169)

Impressions of western Africa, 1858: With Remarks on the Diseases of the Climate and a Report on the Peculiarities of Trade Up the Rivers in the Bight of Biafra, by T.J Hutchinson pg 124)

Early Ceramics from Calabar, Nigeria Towards a History of Nsibidi by Christopher Slogar pg 120)

Early Ceramics from Calabar, Nigeria Towards a History of Nsibidi by Christopher Slogar pg 19)

Flash of the Spirit: African and Afro-American Art and Philosophy by Robert Farris Thompson pg 293)

Early Ceramics from Calabar, Nigeria Towards a History of Nsibidi by Christopher Slogar pg 20)

Étude typographique du système d’écriture nsibidi, des pictos-idéogrammes du Nigeria by Morgane Pierson pg 11

Some Notes on Nsibidi by J. K. Macgregor pg 212)

Étude typographique du système d’écriture nsibidi, des pictos-idéogrammes du Nigeria by Morgane Pierson pg 11)

Some Notes on Nsibidi by J. K. Macgregor pg 212

Fascinating stuff thanks. Over the years I've seen many social media posts celebrating such African writing systems, which is great but I can't help thinking there's a kind of implied sense of inferiority of oral culture in saying, "look Africa had writing too"! I'm not sure I've ever seen a post celebrating the greatness of oral culture as a whole, which seems a tragic omission. The occasional mention of griots was about all I've ever seen. Whole societies and empires functioned perfectly well in Africa without a single word ever having been written down. No one should ever look upon it as inferior. Song, dance, music and storytelling functioned perfectly well in recording and transmitting information. Oral cultures tended to generate prodigious memory skills that written cultures inhibited. Some drum languages were sufficiently complex to recite poetry, is just one example of how evolved these systems could be. I know some academic work has been done on the subject but almost certainly not enough. Given how predominant written culture is becoming in Africa it would be nice to see oral culture celebrated and protected in the way it deserves. If you've written on the subject before could you provide any links please, if not I hope it might inspire a future article.

Thanks for curating and sharing this! Informative.