The political history of the Swahili city-states (600-1863AD): Maritime commerce and architecture of a cosmopolitan African culture

Dotted along the east African coast are hundreds of urban settlements perched on the foreshore, their whitewashed houses of coral rag masonry crowd around a harbor where seagoing dhows are tied, between these settlements are ruins of palaces, mosques, fortresses, tombs and houses; the remains of a once sprawling civilization that tied the African interior with the Indian ocean world.

"Swahili" is one of the most recognizable terms in African culture and history, first as a bantu language -that is one of the most widely spoken languages in Africa with over 100 million speakers- and secondly as a city-state civilization and culture that dominated the 3,000 km long east African coast from Mogadishu in southern Somalia to Sofala northern Mozambique.

The origins of the Swahili city-states are dated to the middle of the 1st millennium AD following the last expansion of the bantu speakers between 100-350 AD that involved small populations of farming and fishing communities who were drawn to the coast from the surrounding interior.1 These "proto-Swahili" communities grew sorghum and millet and subsisted on fish, their architecture was daub and wattle rectilinear houses, a few engaged in long distance trade especially at Unguja Ukuu (on Zanzibar) and Qanbalu (on Pemba) in the early 7th century, by the turn of the 11th century, a number of these villages had grown into sizeable settlements on the archipelagos of Lamu, Kilwa (in Kenya and Tanzania) and Comoros, in the Benadir region of southern Somalia, at Sofala in northern Mozambique and Mahilaka in northern Madagascar. Maritime long-distance trade, while small, begun to increase significantly, a number of local elites adopted Islam and a few timber and mud mosques were built beginning with shanga in 780AD these were later rebuilt with coral stone at 900AD2. From the 12th century onwards, Swahili urban settlements rapidly grew across the coast and nearby islands, state-level societies based on elected elders chosen by a council of the waungwana (elite families) were firmly established on Mogadishu, Kilwa, Zanzibar, Lamu, Mombasa, Barawa, etc, some of the rulers of these city-states took on the title sultan and aggressively competed with other Swahili cities to dominate the increasingly lucrative maritime and overland trade especially in gold from great Zimbabwe, ivory from the interior and the grain-producing agricultural hinterlands and islands. Iron and cloth industries in the cities expanded and substantial construction in coral-stone architecture was undertaken.3

During this time, the ruling elites of the Swahili city states begun to firmly integrate themselves within the wider Islamic world and define their relationships between each other by creating an origin myth for the prominent Swahili cities. This origin myth narrates a story in which a prince (or a princess for the matrilineal Comorians) named Ali, sailed (or fled) from his home in Shiraz in Persia due to his maternal Ethiopian ancestry, he is said to have founded Kilwa, while his brothers (or his seven sons) founded six other towns (the exact list of these towns varies). The oldest version of this origin myth was recorded in the 16th century Kilwa chronicle, subsequent versions would then be written or narrated much later in dozens of cities in the late 19th and early 20th century local chronicles and collections of oral traditions with significant variations in the gender of the founder, the origins of the founders (Shungwaya, Syria and Yemen) and the cities they are claimed to have founded. while early historians first took these origin myths at face value, recent work by archaeologists and linguists has rendered that old simplistic interpretation untenable in light of the overwhelming evidence in favor of autochthonous development that has led them to interpret this mythical origin as representing the tendency of many Swahili to invent conspicuous genealogies for themselves and a way for the Swahili elite to legitimize their Islamic identity by tracing the origins of their founders to Muslim heartlands -which is a common phenomena among Muslim societies across the world. The so-called shirazi and their dynasties were according to the historian Randal Pouwels: "the Swahili par excellence, those original 'people of the coast’ that comprised the original social core of recognized local kin groups, whose claims to residence in their coastal environs were putatively the most ancient".

The term Shirazi (wa-shirazi) was thus used endonymously as a distinctive (self) designation by the people of the coast now known as Swahili.4 The term Swahili on the other hand is exonymous, being derived from the Arabic word for coast, it was first used by Arab writers to refer to the area within the bilad al-zanj (land of the zanj) which they described as beginning at Mogadishu and ending at Sofala. the center/heartland of the zanj was located on the Pemba island by Ibn Said (d. 1275AD) and later by ibn Battuta (visited 1331AD).5

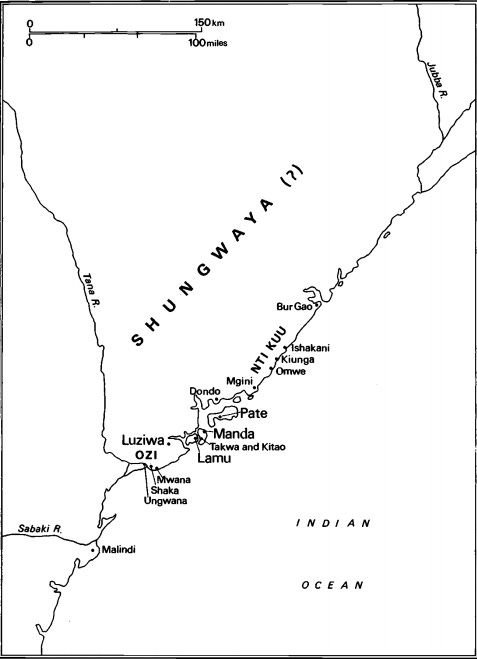

Map of the swahili city-states mentioned in this article (and detailed maps on the Lamu and Zanzibar archipelagos)6

It was during this so-called "wa-shirazi era" that the Swahili cities were at their peak roughly from 1000-1500AD. This golden age ended by the time the Portuguese interlopers arrived in 1498, their predations along the coast and the sack of Kilwa, Mogadishu and Mombasa and brief occupation led to the rapid deterioration of the cities' wealth and the abandonment of several towns, a period of political upheaval followed as multiple imperial powers notably the Ottomans and Omani Arabs, tried to lay claim on the cities while the latter played each of these powers against the other; a number of Swahili cities remained independent until the 19th century when they increasingly came under Omani suzerainty, culminating with the fall of Siyu in 1863.

This article focuses on prominent Swahili cities for each period and weaves their individual threads down to the Omani occupation in the 19th century.

Support AfricanHistoryExtra by becoming a member of our Patreon community, subscribe here to read more about African history, download free books, and keep this newsletter free for all:

On Swahili historiography and writing the political history of the Swahili

The bulk of pre-16th century Swahili historiography is taken from the Kilwa chronicle, the chronicle was written in the mid 16th century and a version of it was copied in Décadas da Ásia by João de Barros in 1552AD and slightly later, an Arabic version of it was written, the latter was then copied in 1837AD and is currently in the British library number "Or. 2666". Sources for post-16th century period include chronicles written in the late 19th and early 20th century such as the kitab al-zunuj from the 1880s, the Mombasa chronicle from 1899, and the chronicles of pate, Lamu, Vumba kuu, Ngazija, Anjouan, Zanzibar and many others (one catalogue of Swahili chronicles found as many as 90 chronicles and traditions from dozens of towns).7 most of which have been translated and published but unfortunately remain undisguisedOther sources for reconstructing Swahili history are the inscribed coins from Shanga, Pemba, Zanzibar, Mafia, Mombasa and Kilwa most of which include the names of Swahili rulers and their dates of issue allowing for a comparison with the written sources.

The Mombasa chronicle, written in 1899 by a Swahili scribe in Mombasa (now at SOAS)

Early Swahili era (500-1000AD)

Swahili urban foundations in the 6th to the 11th century: from Shungwaya to Shanga

The east African coast was already inhabited by the 1st century mostly by a mixed farming and fishing group of bantu speakers among whom a number of proto-urban settlements are mentioned to have been built during the early 1st millennium AD, most notably the entrepot of Rhapta and Menouthias in (Tanzania and Kenya), but these two remain archeologically elusive and predate the distinctive emergence of the Swahili.

The formative period of Swahili history in the second half of the 1st millennium AD was characterized by expansion and migration from their core region of Shungwaya. Shungwaya was a region just north of the Tana river in Kenya that included the coast, offshore islands and the immediate hinterland, terminating at the jubba river in Somalia. This region is attested in the ethnoliguistic history of many of the Sabaki-bantu languages (a sub-group that includes Swahili, Comorian and Majikenda) as their original ancestral homeland from which they eventually migrated southwards along the coast. This is also attested archeologically in the similarity of the "early tana tradition" wares from Mogadishu in the north and asfar south as Chibuene in Mozambique which are ubiquitously present in the earliest levels of all early urban settlements on the coast such as Shanga and Manda (on the Lamu archipelago) in the 8th century8, Tumbe and Kimimba (on Pemba island) in the the 7th and 8th century9 and Unguja Ukuu in Tanzania in the 6th century10. At this stage, some imported pottery, glassware from china, south India and the Arabian coast is found, although dwarfed by local pottery (96% vs 5%), a substantial iron industry developed and most of the elite buildings were rectilinear and built with timber and daub.

Map of the kenyan coast showing the possible location of shungwaya

The first Swahili rulers attested locally were the two issuers of silver coinage from Shanga in the 8th and 10th centuries named Muhammad and Abd Allah respectively11, the sophistication of its silver coinage, the substantial construction of coral stone buildings -which were the earliest of all Swahili cities and by the 14th century numbered more than 200- made shanga the most prominent city of this early period. Shanga was sacked in the 11th century and despite its resurgence in the 14th century, it never became one of the major trading centers of the Swahili coast in the later era but it doubtlessly played an important role in the origin of the culture of the Swahili city states notably, the issuance of coinage and the construction in coralstone. Interpretations of the shirazi myth which suggest that wa-Shirazi were from the Lamu archipelago and migrated to the south therefore position Shanga at the center of Swahili origins.12

Contemporaneous with Shanga was Ras mkumbuu on Pemba island. This city was visited by al-Masudi in 916AD, he referred to it as Qanbalu, and mentioned that it was an important trading town; "among the inhabitants of the island of Qanbalû is a community of Muslims, now speaking the language of the Zanj, who conquered this island and subjected all the Zanj on it" the word “zanj” being a catch-all term for the local east African coastal people. Masudi also noted the trade items of the Swahili particularly gold re-exported from Sofala and iron exports to India, Masudi's observation of Pemba is confirmed archeologically at Ras mukumbuu with its numerous stone houses and tombs and a 10th century coral-stone mosque, the second oldest after Shanga. this was the first mention of Sofala as an economic power-player on the coast: whichever city controlled its trade became the most prosperous. later writers like al-Sîrâfî (d. 979AD) noted a failed attack on Qanbalu by the waq-waq, Buzurg ibn Shahriyar also describes the same group with a massive fleet of 1,000 vessels attacking “many towns and villages of the Zanjis in the Sofala country” in 945-946AD. The waq-waq were an Austronesian group related to the Sakalava of Madagascar, the latter of whom were formidable foes to the Comorian and Swahili city-states in the 18th century.13 Ras Mukumbuu later faded into obscurity by the 15th century.

Ras Mkumbuu’s 11th century mosque and 14th centuy pillar tombs

Classical swahili era (1000-1500AD)

Overview of the 12th-13th century

From the 11th to the 13th centuries, dozens of swahili cities expanded, more than half of the known Swahili cities were established in this period; including Pate, Unguja Ukuu, Mkokotoni, Anjouan, Kisimani Mafia, Kilwa, Manda, Munghia, Gezira, Chibuene; in the 12th century and then Mogadishu, Merka, Barawa; Faza, Lamu, Ungwana (Ozi), Malindi, Gedi, Mnarani, Kilepwa, Mombasa, Chawaka Kizimkazi, Zanzibar town, Kaole, Kunduchi, Jongowe, Mtambwe Mkuu, Ras Mkumbuu, Mkia wa Ngombe, Mduuni, Sanje ya Kati and kilwa.

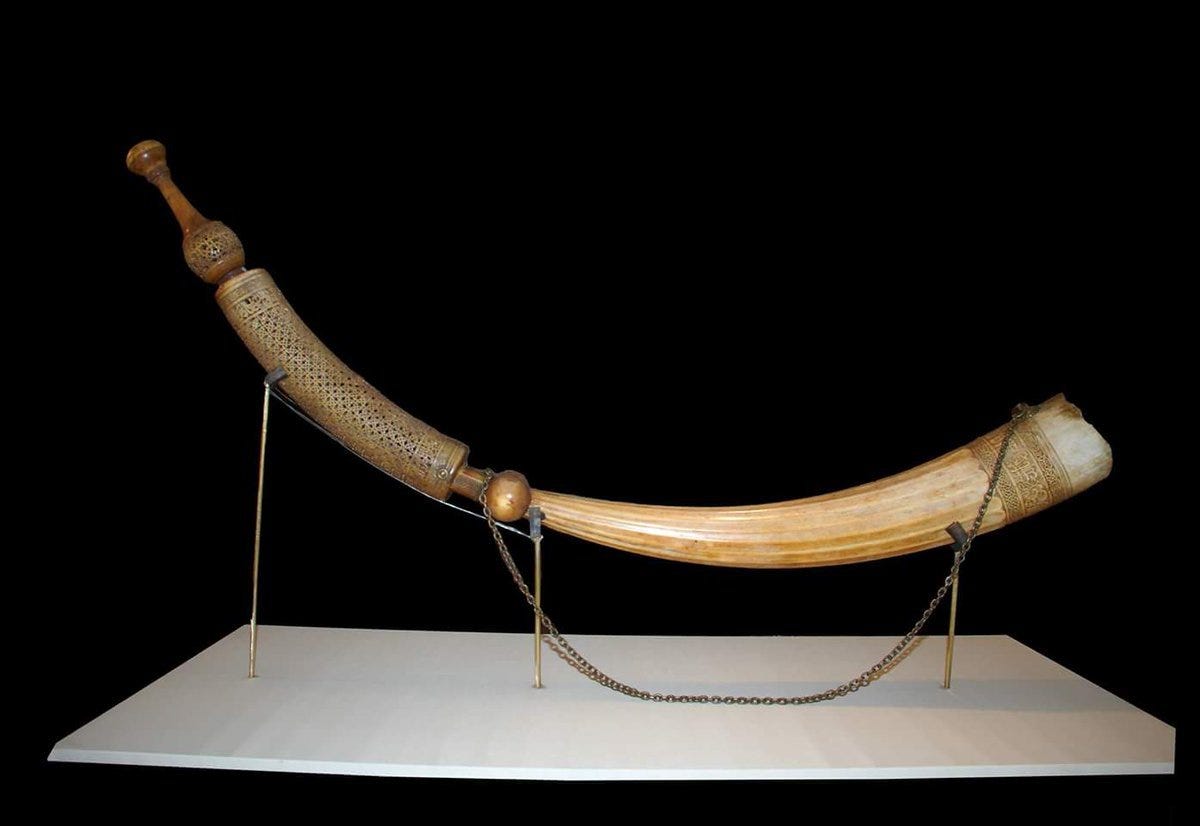

It was in during this early period in the 11th and 12th centuries that the Swahili elites became islamised although largely superficially; the rulers kept the pre-islamic regalia like royal drums, the side-blown siwa, royal spears, medicine bag14, etc. some practiced facial scarification and tooth filing15 is attested and the 15th century Swahili palace of Makame Dume at Pmeba which had a traditionalist segeju shrine built under it16, all of which are common across various African groups.

Lamu’s Siwa (side-blown ivory horn) from the 17th century

The Arabic script was widely adopted, the earliest dated inscriptions come from this era at Barawa in 1104AD and at Kizimkazi in 1106 AD17, and the Swahili became maritime sending both diplomatic and trading missions across the Indian ocean to arabia and as far as china; in the 11th century, An unanmed ruler of Zanzibar (the city called Cengtan/Zangistân ) with the title Amîr-i-amîrân sent an emissary to Song dynasty china in 1071AD, and another arrived at the same court from Mogadishu in 1101AD. by the early 16th century Swahili ships and merchants were active in the Malaysian city of Malacca.18 While none of the Swahili city-states dominated the other politically, a few gained prominence such as Kilwa, Pemba, Zanzibar, Barawa and Mogadisghu; the largest among these cities was Mogadishu in the northern regions and Zanzibar in the southern region.

illustration of a 'mtepe' swahili ship dated to 1277AD from Al-Hariri's Maqamat19

The Swahili from the 12th century to the 13th century: Mogadishu and Zanzibar

Mogadishu was first settled in the 12th century, its described by Yakut (d. 1229AD) as the most important town on the Zanj Sea, governed by a council of elders, while al-Dimashqi (d. 1327AD) refers to it as as the capital of the zanj people belonging to the coast of Zanzibar. Mogadishu’s description as “zanj”, its traditions which hold that the first Mogadishu dynasty was shirazi and its oldest section -shangani, being of bantu derivation, establishes it as the northernmost Swahili city. By the 12th century it had supplanted the neighboring city of Merca as the most prominent city in the benadir region (the southern coast of somalia). Mogadishu's traders had in the early 13th century established ties with the southernmost Swahili city of Sofala that had begun re-exporting gold from the k2-mapungubwe region in south-east Africa, the prosperity that followed this trade is attested by the three oldest mosques which date from this era especially the Fakhr al din mosque built in 1269AD. Mogadishu was visited by Ibn battuta in the mid 14th century who described it as ruled by a Somali (“barbara”) sheikh who spoke maqdishi (a Swahili dialect) and who had by then replaced the council-style government described by Yakut earlier.20

Mogadishu's rulers are attested from the early 14th century on its coinage whose issue continued into the 16th century. Mogadishu first dynasty was replaced in 16th century by the Mudaffar dynasty. Portuguese sources from the early 16th century described as a large city with houses several floors high flourishing on ivory and gold exports and locally manufactured textiles, it was soon bombarded by the Portuguese in in 1499 and in 1518, afterwhich Mogadishu (and the cities of Merca and Barawa) came under the orbit of the mainland Ajuran sultanate in the mid 16th century but remained largely autonomous.21 it gradually declined until 1624 and it was taken by the darandolla (somalis of the Hawiye clan) who established themselves at shangani, this fall continued into the 18th century as Mogadishu’s population and prosperity declined along with the neighboring cities of Merca and Barawe that had by then been reduced to villages, it was then bombarded and taken by the Omanis in 1828AD.22

The most prominent of the southern cities in the 12th and 13th centuries was Zanzibar. Yaqut, writing in 1220AD, described Zanzibar as a center of trade and Tumbatu as the new location of the people and seat of the king of the Zanj, its reach expanding to Shangani, and to Fukuchani, it also traded with the hinterland cities of Kunduchi and Kaole23 that were flourishing at the time, Zanzibar rapidly declined by the early 14th century and Ibn battuta passed it without mention most likely because the ruling elites at Tumbatu moved to Kilwa after having deposed Kilwa's previous dynasty in a coup d'état at the end of the 13th century24. It was never an important power in the later centuries until its occupation by the Omanis in the mid 18th century. (we shall return to this below)

Old town Mogadishu, the 12th century mosque at Tumbatu

The Swahili from the 13th to the 14th century: Kilwa

The city of Kilwa was first settled in the 9th century but had grown significantly in the second half of the 11th century under its first attested ruler Ali bin al-hassan, he issued silver coins with his names engraved on them and rebuilt the old Kilwa mosque with coralstone. Kilwa extended its control to the island of Mafia by the 13th century and later Songo mnara, Sanje ya kati and much of the "southern Swahili coast”. Kilwa took sofala from Mogadishu in the late 13th century and prospered on reexporting gold that was now controlled by the kingdom at Great Zimbabwe. At the turn of the 14th century, Kilwa’s first dynasty was deposed by the Mahdahali dynasty from a nearby swahili city of Tumbatu under the new ruler, al-Hassan Ibn Talut, the most illustrious ruler of this dynasty was al-Hassan bin sulayman who reigned in the early 14th century, he issued trimetallic coinage and built the gigantic ornate palatial edifice of Husuni Kubwa, expanded the great mosque, made a pilgrimage to mecca (the first of several Kilwa sultans) and hosted the famous Moroccan traveler Ibn Battuta who described the city as elegantly built entirely with timber and the inhabitants as Zanj with facial scarifications25Ibn Battuta’s account was accurate for Kilwa which in the early 14th century whose houses at the time were mostly built with wood save for the great mosque and the palace (and unlike Shanga, Pemba, Tumbatu, Mogadishu, Gede and a few other cities where a significant number of houses had already been built in coralstone).

Kilwa's fortunes briefly decline in the second half of the 14th century due to the collapsing gold prices on the world market and the black death but revived at the turn of the 15th century with heavy investment in coralstone building around the city and the nearby island on Songo mnara, during this century, the city-states of Mombasa and Malindi rose to prominence challenging Kilwa's hegemony and setting off the latter's gradual decline.26

In 1505 kilwa was sacked by the Portuguese, the first of a number of assaults on the city including one from the mainland Zimba in 1588 that further impoverished the city, the Portuguese took Sofala and gold exports plummeted from 5-8 tonnes a year to 0.5 tonnes under Portuguese control.27, no buildings were constructed through the century while Kilwa was under Portuguese suzerainty the latter of whom had established themselves at Mombasa. The city fell into political turmoil and a number of assassinations, invasions and rebellions are recorded in the first half of the 17th century. By the end of the 17th century, the Portuguese had been expelled from much of the coast by a combined Swahili and Omani force.28

Kilwa's prosperity was revived in the late 17th and early 18th century, under sultan Alawi and then queen (regent) Fatima bint Muhammad's reign when ivory trade with the Yao (an interior group) expanded, a fortified palace was built on top of the 15th century palace and the grand mosque was repaired, Kilwa’s influence extended to the cities of Mafia and Kua. late in the 18th century, a series of weak rulers saw the city declining and increasingly coming under Omani suzerainty who built the Gezera fort around 1800, In the early 19th century and focus shifted to Kilwa kivinje and Kilwa’s last ruler, sultan Hassan, was exiled by the Omanis in 1842.29

gold coins of Kilwa sultan al-Hassan Sulayman from the 14th century

Kilwa’s great mosque built in the 11th century and a 14th century elite house in Songo Mnara

Late Swahili era 1500-1850

The Swahili from the 15th to the 16th century: Mombasa and Malindi

From the 15th to 17th century the most prominent Swahili cities were Mombasa and to a lesser extent, Malindi. They both derived most of their prosperity from the agricultural bases in their hinterlands and surrounding islands such as the growing and exportation of rice and millet, mangrove wood for construction, exportation of locally made iron and the manufacture and trade of cotton textiles.30 Such prosperity based on controlling the hinterland agricultural produce is first utilised in the nearby hinterland cities of Mnarani and Gedi but especially the latter, which reached its apogee in the 13th and 14th century when heavy investment in monumental coralstone architecture was undertaken with hundreds of stone houses constructed, before it gradually declined by the 16th century likely due to the ascendance of the neighboring cities of Malindi and Mombasa. Mombasa’s prosperity stagnated while it weathered a succession of catastrophic Portuguese attacks in 1505, 1528/29 and 158931, its internecine wars with Malindi and against the hinterland groups; the Zimba and Segeju forced it into a period of gradual decline by the end of the century when it became the Portuguese seat on the coast following the construction of fort Jesus. This fort was in the late 17th century wrestled from the Portuguese by a Swahili-Omani force, Mombasa was thereafter ruled by an alliance of the old council and the Mazruis of Oman origin. The latter gradually supplanted the former and the city’s prominence was slowly revived by the 1770s controlling the agriculturally rich Pemba island and their immediate hinterland, but the Mazrui’s meddling in the affairs of the neighboring city-state of Lamu’s led to a war in 1812-14 which it and its allied city of Pate, was defeated by Lamu allied which was allied with the Busaid Omanis. the latter took the city in 1837.32

Mombasa beachfront in the 1890s, Malindi 15th century Pillar tomb

Interlude: Portuguese, Ottoman and Oman imperial claims on the Swahili coast in the 16-17th century

The 16-17th century was a time of great social and political upheaval on the Swahili coast that witnessed radical shifts in trade relations as the city’s wealth attracted the attention of multiple imperial powers such as the Ottomans, Portuguese and Omanis, who sought to dominate the coast. The Swahili cities allied with some of these powers against the others and against other Swahili foes, for the southern Swahili cities: old trade kingdoms like great Zimbabwe and Mutapa collapsed and were replaced by the Maravi and Yao who were much closer them, the Omanis had sacked fort Jesus in 1696 and expelled the Portuguese but the Swahili soon grew weary of their former partners who had garrisoned Pate, Mombasa, Zanzibar and Kilwa; the Swahili threw them out of fort Jesus by the turn of the century and all cities were afterwards largely autonomous, this state of affairs lasted until the resumption of Busaidi-Omani expansions in the mid-18th century33. This period also witnessed the ascendance of the Comorian city states whose development, culture and customs mirrored the Swahili city states and whose language was closely related.

The Swahili and Comoros from the 17th to the 18th century: the rise of Anjouan

A number of Comorian city-states rose to prominence during the 15th to 18th century. the Comoros archipelago had been settled by Comorian-bantu groups in the second half of the 1st millennium, these comprise the bulk of its current population on the four islands of Ngazidja/Grande Comore, Mayotte, Mwali and Nduzuani/Nzwani, they practiced mixed farming and fishing and participated in trade with the Swahili cities and the Indian ocean. The Matrilineality of Comorian inheritance (which existed in some Swahili groups as well) created a curious version of the Shirazi myth where instead of the founder (prince Ali) being a man, it was a two unammed Shirazi princesses who are said to have came to Ngazidja34 and Mayotte and intermarried with local elites such that succession followed their line.35 the cities of Old sima and Domoni grew into important towns between the 11th and 14th century including the construction of coralstone houses and mosques and trade based on exportation of the commodities rice, millet and chlorite schist flourished. The islands came under Kilwa's orbit in the 15th century, an offshoot Kilwa elite then founded the sultanate of Anjouan at Nzwani island in the early 16th century and substantially expanded the capital Domoni, later moving it to Mutsamudu and uniting most of the island. Anjouan owed its wealth inpart to its better harbor which by the 17th century was a favorite stopover for French, Dutch and English ships whose demand for food surpluses further led to the economic prominence of the state represented by the construction of more stone houses, public squares and baths and a large fortress. Anjouan later declined due to Sakavala raids in the late 19th century the other islands eg Ngazidja were mostly divided under many local rulers most prominent being those of Bambao whose capital was Iconi, these sultanates were then united in the late 19th century on the eve of French colonialism.36

The 18th century fortress at Mutsamudu on Nzwani and the 16th century palace of the Bambao ruler at Iconi in Grand Comore/Ngazidja

The Swahili in the 18th century: Pate and the rise of Lamu

Lamu and Pate's ascendance in the late 16th century owed much to Mombasa's decline, Pate in particular secured a standing as the most important supplier of ivory on the coast and managed to establish trade relations with mecca and the red sea by 1569AD avoiding the then Portuguese controlled Mombasa. Skippers from Pate plied their seagoing trade north to Barawa, Merka and Mogadishu, The 18th century saw a marked resurgence in relations between the central Swahili core (the Lamu and Zanzibar archipelagos) and the northerly Swahili of the Benadir region especially the city of Barawa37; the latter of whom were reportedly ancestors of the shomvi Swahili clan prominent in the Rufiji delta region of Tanzania, these revived the collapsed cities of Kaole and Kunduchi in the 18th century and founded Bagamoyo in the 19th century38 The same century was a period of renewed prosperity for the Swahili cities especially Lamu, Pate as attested by elaborate coral construction, detailed plasterwork in mosques and homes, and voluminous imported porcelain.

By the late 18th century succession disputes at Pate led to Lamu upending Pate's position as the most prominent city on the coast (although sharing this position with the newly emerging city of Siyu). Lamu's wealth was based on the same agricultural economy as Mombasa involving patron-client relationships with hinterland cultivators, coupled with its better harbor. Lamu had a typical Swahili council-style government of waungwana where an elder from the two main factions was chosen rather than a sheikh. The city's population grew to around 21,000 in the early 1800s, its preeminence was cemented following the ‘battle of Shela’ in 1812-14 when Lamu defeated a combined Pate and Mombasa force, later placing itself under the protection of the Busaidi Oman sultan Sayyid Said who was increasingly setting his eyes on the coast, Pate was thereafter reduced to a small village by 1840s.39

18th century elite house in the city of Pate, Lamu beachfront

Swahili epilogue in the early 19th century: the Omani capital at Zanzibar and the fall of Siyu.

While Zanzibar had flourished before the 14th century, it was for a minor town for much of the succeeding period, it too switched alliances between the Omani and Portuguese during the 16th/17th century upheavals and attained autonomy at the turn of the 18th century under their local ruler titled Mwinyi Mkuu, this lasted until 1744 when the Busaid Omanis installed a governor on Zanzibar who initially shared power with the local ruler but increasingly used Zanzibar as a base to conquer the rest of the Swahili cities and the Mwinyi mkuu was soon reduced to a ceremonial figurehead. The victory of Omanis’ Lamu allies at the battle of shela established them as the dominant power of the coast, they then went on to seize the island of Pemba (which was Mombasa's agricultural base for rice) to weaken the Mazruis of Mombasa, the latter sought to ally with the British against the Busaidi Omanis who had now surrounding them but the Omanis had much firmer ties with the British, in the end, Mombasa became tributary to the Omanis who blockaded it leading to its collapse in 1837.40

The last major Swahili holdout was Siyu whose origins date to the 15th century. Siyu had flourished alongside Lamu in the late 18th/early 19th century with a population of more than 20,000 it was as major scholarly city and the center of a substantial crafts industry under its ruler Bwana Mataka. The Omani sultan attacked Siyu several times starting in the late 1820s prompting Bwana Mataka to build the Siyu fort, the Omanis then launched another attack in the late 1840s but this too was repulsed, it was only after the last attack in 1863 that Siyu finally capitulated after a 6 month-long siege by Sultan Seyyid Majid,41formally marking the end of Swahili independence.

Siyu fort

Conclusion

The Swahili city-states are the archetype of African cosmopolitanism, their political system of “oligarchic republics” governed by a council of elders was fairly common on the African mainland especially in west-central Africa, as well as their traditionalist regalia and customs, their spatial settlement -whose enclosures followed the style of the kayas of the Majikenda- and their architecture which expresses forms derived from local materials such as mangrove poles, coralstone, thatch and coral-lime. Yet the Swahili were also cosmopolitan adopting and indigenizing elements from across the Indian ocean littoral. Swahili social structure was defined by diversity and ethnic multiplicity and its political life was characterized by binaries organized around principles of inclusiveness versus exclusiveness. Its this aspect of Swahili dynamism that confounds some observers whose interpretations of Swahili history and culture are reductive; preferring to misattribute Swahili accomplishments to other groups. Swahili society preserves the legacy of Africa's integration into the Indian ocean system and its wealth is a testament to the active role Africa merchants and commodities played in global history.

for more on African history, please subscribe to my Patreon account

The East African Coast c. 780 to 1900 CE by R. Pouwels pg 253

The Swahili World by Stephanie Wynne-Jones et.al, pg 140-145

The swahili city state culture by N. T. Hakansson pgs 470-472

Horn and cresecnt by R. Pouwels pg 34-37

The swahili by M. Horton pg 16

this map is taken from “The Swahili World” by Stephanie Wynne-Jones et.al

A History of Swahili Prose, Part 1 by J. D. Rollins, pgs 29,30

R. Pouwels, pg 10-16

Stephanie Wynne-Jones et.al, pg 163

Stephanie Wynne-Jones et.al, pg 169

Shanga by M. Horton, pg 377

The swahili horton, pg 50

Stephanie Wynne-Jones et.al, pg 234, 369, 370

R. Pouwels, pg 27,28

China and East Africa by M. Kusimba, pg 73

Swahili Archaeology and History on Pemba, Tanzania by A. LaViolette, pgs 149-151

Swahili Origins by J. de V. Allen, pg 183

Stephanie Wynne-Jones et.al, pg 433, 376

Trade in the Ancient Sahara and Beyond by D. J. Mattingly et.al, pg 147

medieval mogadishu by N. chittick pg 48-50)

J. de V. Allen pg 156

Muqdisho in the Nineteenth Century by Edward A. Alpers, pg 441-445

Southern Africa and the Swahili World by Felix Chami pg 15

Stephanie Wynne-Jones et.al, pg 242

The Indian Ocean in World History By Edward A. Alpers pg 52

Kilwa a history by J.E.G sutton pg 123-132)

Port cities and intruders by M. Pearson, pg 49

Ivory & Slaves in East Central Africa by Edward A. Alpers, pg 61-62

A Revised Chronology of the Sultans of Kilwa in the 18th and 19th Centuries by Edward A. Alpers pg 160

R. Pouwels, pg 7

Stephanie Wynne-Jones et.al pg 233

R. Pouwels, pg 98-100

Stephanie Wynne-Jones et.al, pg 519-523

Becoming the Other, Being Oneself by Iain Walker pg 60-65

Islands in a Cosmopolitan Sea by Iain Walker, pg 34-39

The Comoro Islands in Indian Ocean Trade before the Nineteenth Century by M. Newitt pgs 145-160

R. Pouwels, 39-41

Historical Archaeology of Bagamoyo by Felix Chami

The battle of shela by R. L. Pouwels pgs 370-372

Slaves, spices, & ivory in Zanzibar by Abdul Sheriff, pg 26-30

Omani Sultans in Zanzibar by Ahmed Hamoud Maamiry, pg 16

This is article should be widely shared. It is one of the best and most comprehensive ever written of the Swahili Nations. Please also refer to Prof. Chap Kusimba's works.

Not sure about the 'diversity' elements being something worth emphasising about the Swahili given that the evidence presented in this article suggests a pretty homogeneous culture that resisted and absorbed what elements it liked from conquerors and others, and eschewed the rest.

That said this was a pretty good article, love learning about the Swahili people.