The power of the pen in African history; composing, editing and manipulating history for political legitimation: comparing Ethiopia's Kebrä Nägäst and Songhai's Tārīkh al-fattāsh.

Until recently, Africa was considered by many as a land without writing, where all information about the past was transmitted orally and griots sung praises of ancient kings, and that when a griot dies, “its like a library was burned down". But the discovery, translation and study of the voluminous collections of manuscripts from across the continent has rendered obsolete this inacurate and fanciful description of the African past; from Senegal to Ethiopia, from Sudan to Angola, African scribes, rulers, scholars and elites were actively engaged in the production of written information, creating sophisticated works of science, theology, history, geography and philosophy. The discursive traditions of these african writers weren't restricted to the elite as its often misconceived but was widely spread to the masses to whom these writings were read out orally in public gatherings such that even those who weren't literate were "literacy aware", its within this vibrant intellectual milieu that literacy became an indispensable tool for legitimizing political authority in pre-colonial Africa.

The Tarikh al-fattash and the Kebra nagast are among the most important pre-colonial African works of historical nature, the Tarikh al-fattash is a chronicle that provides an account of history of the west African empires until the 16th century, mostly focusing on the history of the Songhai rulers and their reigns while the Kebra Nagast is a historical epic about the origin of the the "solomonic" dynasty that ruled medieval Ethiopia from 1270AD to 1974. These two documents written by African scribes in what are now the modern countries of Mali and Ethiopia, have been widely reproduced and studied and are some of Africa's best known works of literature. Because of the intent of their production, both share a number of similarities that are essential in understanding the power of the written word in pre-colonial African concepts of authority and its legitimation; they include eschatological themes, claims of divine authority, claims of authorship by high profile scholars, and bold re-tellings and interpretations of historical themes found in major religious texts. While the two differ structurally, and are also different from most historical literature in Africa, the resemblance in their themes, the message they intend to convey and the enigmatic nature of their production, circulation, disappearance and rediscovery sets them apart from the rest of Africa’s historiographical documents.

This article explorers the political context and intellectual projects that influenced the production of these two documents as well as the centrality of literacy in the concepts of power and its legitimation in pre-colonial Africa.

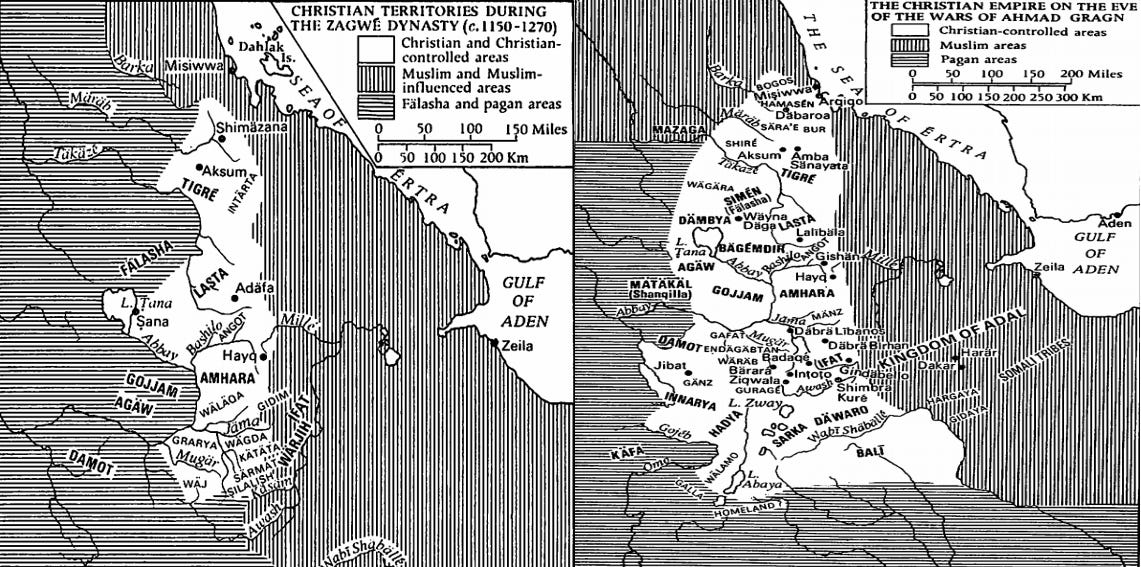

Maps of the Ethiopia in the medieval era and Maps of the Massina empire showing the states, regions and cities mentioned

Support AfricanHistoryExtra by becoming a member of our Patreon community, subscribe here to read more about African history, download free books, and keep this newsletter free for all:

The “Glory of the Kings”: authorship and themes of the Kebra Nagast, and politics in medieval Ethiopia.

The Kebra Nagast is an Ethiopian epic whose authorship is traditionally attributed to Yeshaq, the nebura-ed of the city of Aksum who is mentioned in the document’s colophon, he worked under the patronage of Ya’ibika Egzi a governor of Intarta (in what is now the Tigrai region of Ethiopia). Yeshaq, a highly learned scholar who was writing around 1322, says that he was translating the document into Ge'ez from Arabic, which inturn was originally in Coptic and written in 1225.1 The most comprehensive study of the Kebra nagast reveals that it wasn't the singe coherent version in the form that survives today but one harmonized and edited over several centuries by several authors after Yeshaq, around a central theme that was in line with the forms of political legitimation that existed in medieval Ethiopia, and that the Kebra Nagast was later adopted by the Solomonic dynasty as their own national epic in the 14th century right upto the fall of the dynasty in 1974.2

The central theme of Kebra nagast is a story about the biblical queen of Sheba whom it is says was the ruler of Ethiopia, she visited Solomon the king of Israel (his reign is traditionally dated to 950BC) with whom she gave birth to a son named David (called Menelik in later versions), this David later returned to Israel to visit his father Solomon and the latter offered David kingship in Israel but he turned it down, so the high priest of Israel, Zadok, anointed him as King of Ethiopia, and Solomon gave David a parting gift of the covering of the ark of the covenant, but the sons of Zadok, moved by divine encouragement, gave David the ark of the covenant itself which they took from the temple and it was carried to Ethiopia, upon arriving home, David received the crown of Ethiopia from his mother and the Ethiopian state abandoned their old faith for the Jewish faith and from then, all Ethiopian monarchs could only rule if they traced their lineage directly to him.3 It also contains eschatological prophesy about Kaleb's sons the first of whom will reign in Israel along with the one of the roman emperor’s sons while the other will reign in Ethiopia, but on Kaleb's abdication, both sons will fight and God will mediate between them for one son to remain reigning over Israel and Ethiopia while the other reigns over the realm of the spirits.4

The kebra nagast largely draws from old testament themes, but also includes materials from the new testament, apocryphal works, patristic sources and Jewish rabbinical literature, but it diverges from most of these by relying less on mythical beings and instead choosing to include citations from real personalities such as the 4th century figures st. Gregory the illuminator (d. 331 AD) and Domitius the patriarch of Constantinople.5 Its composition during the 13th-14th century occurred at a time when the highlands of Ethiopia state were contested by three Christian polities (as well as some Muslim states), the two most important were the Zagwe Kingdom (lasted from 1137-1270) which was in decline, and the incipient Ethiopian empire (lasted from 1270-1974) which was a fledging state in the late 13th/early 14th century, subsuming several smaller kingdoms in the region especially during the reign of Amda Seyon (r. 1314-1344) with whom Yeshaq was a contemporary. The other state was the enigmatic polity of Intarta ruled by Ya’ibika Egzi who is termed as "governor" in the document, he ruled semi-autonomously in the region around the city of Aksum and its suggested that he rebelled against Amda Seyon's empire possibly with ambitions of his own expansion6, it was under Ya’ibika Egzi’s patronage that Yeshaq wrote the earliest version of the kebra nagast.

The oldest extant copy of the Kebra Nagast is the 15th century manuscript (Éthiopien 5) at the Bibliothèque nationale in Paris, (although its this early date is disputed7), other earlier versions include an Arabic version from the 15th century that was written by a christian Arab in Egypt, its mostly similar to the first version but diverges in some parts mentioning that David forced the priests of Israel to carry the Ark of the covenant back to Ethiopia8, another is a 16th century Ethiopian version that was reproduced by a portuguese missionary Francisco Álvares, and an ethiopian version that was written in the late 16th-17th century9. All versions mention the queen Sheba and king Solomon relationship and the Israel-centric origins of the ethiopian empire's dynasty but differ on the relics taken from israel with some versions referring to an Ark, or to stone tablets of Moses.

The political and religious context of medieval Ethiopia: exploring the claims in the Kebra Nagast.

Inclination towards old testament customs in the the late period of Aksum was in place by the 11th century10, the association of queen Sheba's kingdom with the region of Ethiopia was in present in external accounts as early as the 11th century11 , claims of Aksumite lineage as well as the scared status of the city of Aksum may have been present during the Zagwe era although they were not used by the Zagwe rulers themselves but rival dynasties, the conflation of the Kush (biblical Ethiopia) with the kingdom of Aksum and later Abyssinia (modern Ethiopia) was present in external accounts as early as the 4th century, as well as some in some internal accounts12, and the claims of divine rule by kings in the region of Ethiopia were in place during the early Aksumite era both in the pre-Christian and Christian times.13 The existence of an kingdom named saba in the 9th/8th century BC has been confirmed by the dating of the monumental architecture at the city of Yeha as well as inscriptions that list king Saba14. But the first external confirmation most of parts of the Kebra nagast story comes from Abu al-Makarim, a 13th century Coptic priest in Egypt who collected information about Ethiopia under the zagwe kingdom from travelers who had been there (the Zagwe King Lalibela, who ruled in the first decades of the 13th century, would have been his contemporary), he mentions that the Zagwe kings traced their descent from the biblical priestly family of Moses and Aaron and that descendants of the house of david (priests) are in attendance upon an ark in the Zagwe capital adefa (modern city of Lalibela)15 this "ark" was according to his description a small wooden altar containing Christian crosses as well as tablets of stone "inscribed with the finger of god" and it was actively used during the ecclesiastical activities in a manner that was similar to the ethiopian tabot rather than the revered ark of the covenant.16 The “Juda-izing” elements of the Ethiopian state were thus inplace by the reign of Lalibela and were likely deliberately adopted by the Zagwe kings as new forms of legitimacy, Lalibela was the first of the Ethiopian rulers under whom the ark is mentioned, he established relations with the Ayyubid sultan al-Adil I (r. 1200-1218), who controlled Egypt and Jerusalem, and Lalibela’s successor Na'akuto-La'ab built a church at lalibela named after Mount Zion (Seyon), marking the earliest allusion to the holy mountain of Jerusalem in Ethiopia, as well as the origin of the tradition that the Zagwe rulers sought to turn Lalibela into the “second Jerusalem”, their success at this endeavor is evidenced by their veneration as saints in the Ethiopian church.17

Not long after Lalibela had passed on, the Zagwe kingdom was embroiled in succession disputes and declined, falling to what later became the Ethiopian empire led by Yekuno Amlak (r.1270-1285), by the time of the reign of his successor Yigba Seyon Salomon (r. 1285-1294), the Zion connection in the Ethiopian court was firmly in place evidenced by this king’s adoption of “Seyon” and “Solomon” in his royal name, and a firmer relationship was also established with the Ethiopian community installed at a monastery in Jerusalem likely during his father's reign. The dynasty of Yekuno Amlak therefore, continued the judaizing tradition set by the Zagwe kings but inorder to reject the claims of the Zagwe origins from the priestly lineage of Moses and Aaron, these new kings chose to trace their descent from Solomon and his Ethiopian son David (hence the name “solomonic dynasty”), and its during this time that Yeshaq enters the scene, combining the various traditions circulating in and out of Ethiopia including; the Solomon and Sheba story, the biblical references to Ethiopia and divine rule, into a bold and ambitious project that was initially intended for his patron Ya’ibika Egzi18, but was soon after adopted by the conqueror Amda Seyon who defeated Egzi whom he considered a rebel writing that "God delivered into my hands the ruler of Intarta with all his army, his followers, his relatives, and all his country as far as the Cathedral of Aksum"19.

Completing the Kebra Nagast intellectual project; reception and support of an Ethiopian tradition

After its adoption by the Solomonic dynasty, the stories in the Kebra negast would be crystallized and conflicting accounts harmonized with each subsequent copying, in line with the firmer centralization of Ethiopia’s monastic schools (and thus, its intellectual traditions) that occurred under the king Zera Yacob (r. 1434-1468) which reduced the multiplicity of the competing scholarly communities in the empire.20 The earliest version recorded externally was by the Portuguese missionary Francisco Alvares in the 1520s who says it was first translated from Hebrew to Greek to Chaldean (aramaic) then to Ge'ez, it mentions the story of Solomon and Sheba as well as his son David who departed from Israel to rule Ethiopia, although there is no mention of David taking the ark21, an Ethiopian contemporary of Alvares was Saga Za-ab the ambassador for king Lebna Dengel (r.1508-1540) to Portugal who mentions the existence of the Kebra nagast, the story of Sheba, Solomon and David, saying that the latter bought back "tables of the covenant"22,a later version similar to this was recorded by Portuguese historian Joao de barros in 153923, and another by the jesuit priest Nicolao Godinho in 1615 who presented an alternative account about the origin of queen Sheba whom he conflated with the kingdom of Kush's Candaces (the queens of Meroe) but nevertheless repeated the story of the Ethiopian king David and the Solomonic lineage of the Ethiopian rulers24, arguably the oldest explicit citations of the Kebra nagast in an Ethiopian text was in Galda marqorewos' hagiography written in the 17th century "this history is written in the Kebra Nagast… concerning the glory of Seyon the tabot of the Lord of Israel, and concerning the glory of the kings of Ethiopia (Ityopya) who were born of the loins of Menyelek son of Solomon son of David.25

Needless to say, by the early 16th century the Kebra Nagast had for long been the official account of the national and dynastic saga of the Solomonic rulers of Ethiopia in its current form and had attained importance in the educated circles of Ethiopia and was considered authoritative26, it was also included in a chronicle of King Iyasu I (r. 1682-1706) who consulted the text on a matter of court precedence.27 the central story of the kebra nagast had been formulated quite early by the 14th-15th century and versions of it were edited and harmonized with each newer version becoming the accepted edition over time28.

Palaces of Susenyos built in the early 17th century at Danqaz and Gorgora Nova

Place of Iyasu I built in the 18th century in Gondar

Little, if any challenge of its claims can be gleaned from contemporary Ethiopian texts and it seems to have been wholly accepted by the Ethiopian church and the Ethiopian court, and the majority of the population, its claims proved to be effective with time, as all Ethiopian monarchs claimed Solomonic descent regardless of the political circumstances they were faced with (even during the “era of princes” when the empire briefly disintegrated, only those with true Solomonic lineage would be crowned) . The only voice of critique came from the Portuguese missionaries resident in Ethiopia who reproduced the story but dismissed it as a fable, although their analysis of the kebra nagast was of little importance to the Ethiopians on account of the very negative perception they created of themselves while in Ethiopia. The portuguese priests had converted king Susenyos (r.1606-1632) to catholism in 1625 and until 1632, it was the state religion of Ethiopia but it was poorly received in the empire largely due to the actions of the Jesuit priests whose radical religious reforms were met with strong rejection from the elites, the Ethiopian church and the general population ultimately resulting in a civil war that ended with Susenyos rescinding his imposition of catholism on the state29 and his successor Fasilidas (r. 1632-1667) permanently expelling the Jesuit priests from Ethiopia. These events not only reduced the credibility of the Portuguese and their faith in Ethiopia, but may have buttressed the authority of the Ethiopian church and served to affirm the stories presented in the Kebra nagast which now gained a quasi-biblical status across the empire, and the Kebra nagast would from then on be envisaged as an unchanged, original document. As historian Stuart Munro-Hay writes; "The regal propaganda machine of Solomonic Ethiopia was startlingly effective in its long-term results This book that took several centuries to complete is the living proof of how, in combination with the church, the Solomonic dynasty created a politico-religious manifesto for its rule that remained enshrined in the very heart of the state until 1974. Its basic premises were actually written into the mid-20th century Constitution of the Ethiopian empire.30 Virtually all sections of the Kebra nagast indicate the project's intent of political legitimation, even the apocalyptic rhetoric included in its only section with a historical event (about the Aksumite king Kaleb and his sons) was "employed in a rather unconventional way, not to console a persecuted minority, but to legitimate a new elite, as a means to establish a new political, social, and religious order”31 its for this reason that despite the complex circumstances of its production "There is virtually unanimous agreement among scholars as to the political motive. The Kebra nagast was written to justify the claims of the so-called Solomonid dynasty founded by Yekuno Amlak over against those of the Zagwé family who had held sway for well over a century"32

Folios from the 15th century Kebra Nagast at the Bibliothèque nationale de France (shelfmark: Éthiopien 5 )

The “chronicle of the Researcher”: the Tarikh al-Fattash and legitimizing power in west africa.

The Tarikh al-fattash is a west African chronicle whose authorship is contested, most west African historians initially regarded it as a work that was compiled over several generations by its three named authors: Mahmud Ka‘ti, a 16th century scholar; Ibn al-Mukhtar, a 17th century scholar; and Nuh al-Tahir, a 19th century scholar.33 But the most recent and comprehensive study of the document reveals it to be a largely 19th century text written by Nuh al-Tahir a scribe from the Hamdallaye caliphate (also called the Massina empire in what is now modern Mali) who substantially rewrote an old 17th century chronicle of Ibn al-Mukhtar called Tarikh ibn al-Mukhtar ( al-Mukhtar was a Soninke scribe from the Dendi kingdom; an offshoot of the Songhai empire after fall to morocco). Nuh al-Tahir greatly re-composed the older text by adding, editing and removing entire sections of it. The chronicle of Tarikh al-fattash is an account of the history of the west African empires of Ghana, Mali and Songhai but mostly focusing on the history of the Songhai heartland from the 11th century (kingdom of Gao) upto the reigns of each of the emperors (Askiyas) of Songhai in the 15th and 16th century (especially Askiya Muhammad r. 1493-1528), through Songhai’s fall to the Moroccans in 1591 and upto the reign of Askia Nuh of Dendi-Songhai in 1599. Its part of a wider genre of chronicles called the “Tarikh genre” that is comprised of three thematically similar documents of west African history that include the “Tarikh al-sudan and the “notice historique”, all three of which were written by west African scribes, whose intent, as historian Paulo de Moraes Farias puts it "aimed at writing up the sahel of west africa as a vast geopolitical entity defined by the notion of imperial kingship". This bold project of the Tarikh genre culminated in the elevation Askiya dynasty of Songhai to the status of caliphs inorder to rival the claims of the caliphs of morocco as well as to persuade the the Arma kingdom (an offshoot kingdom comprised of Moroccan soldiers left over from the Songhai conquest who were now independent of Morocco and controlled the region between the cities of Timbuktu and Gao) to accept a social political pact with the Askiyas and reconcile both their claims to authority without challenging the Arma's rule.34 These chronicles were thus written under the patronage of the Askiyas of Dendi-Songhai with the intent of reconciling their authority with that of the Armas; as stated explicitly in Ibn al-Mukhatr's chronicle, he wrote it under the patronage of Askiyà Dawud Harun (r. 1657 and 1669).35

In the Tarikh al fattash chronicle, Nuhr al-Tahir frames the entire document as a celebration of Aksiya Muhammad above all others, he includes sections where the Askiya, on his pilgrimage to mecca, met with a shariff who invested him with the title "caliph of Takrur" (Takrur was a catch-all term for west African pilgrims in mecca and thus west Africa itself), the Askiya then proceeded to Mamluk Egypt on his return where he discussed with the renown scholar al-Suyuti (d. 1505) who told him that there were 12 caliphs prophesied by the prophet Muhammad and that all ten have already passed but two are yet to come from west Africa one of whom was the Askiya himself and the other would come after him, that he will emerge from the Massina region (central Mali) and from the sangare (a group among Fulani-speakers), and that while the Askiya will fail to conquer the land of Borgo (in south-central Mali), his successor will complete its conquest.36 Nuh al-Tahir also deliberately adds the nisba of al-turudi to the Askiya's name to link him (albeit anachronistically) with the torodbe lineage of fulani clerics that emerged in the 18th century among whom was Ahmad Lobbo37. On his journey back to Songhai the Askiya meets a group of jinn who also repeat al-Sayuti's prophesy, other sections include quotations of similar prophesies by maghrebian scholars such as Abdul-Rahman al-Tha'alibi (d. 1479) and al-Maghili (d. 1505), both of whom are said to have predicted the coming of Ahmad lobbo38, Nuh al-Tahir heavily relies on al-Suyuti's works in which the latter scholar writes about the expected coming of the two caliphs, and other works where he writes about the awaited arrival of the “renewer of the faith” (mujaddid), both of these works were popular in west Africa and widely read across the regions schools.39 Its important to note that Nuh al-Tahir doesn’t construct the story out of thin air, but bases it on the real and documented pilgrimage of Askiya Muhammad, his meeting with the Abbasid caliph of cairo, who made him his vice in the land of Takrur (rather than a meccan sharif), his meeting with al-Suyuti and other scholars in cairo and the his correspondence with al-Maghili (although none contains this prophesy) as well as the Songhai emperor Askiya Muhammad’s legacy as the empire’s most successful conqueror all of which is recorded both internally and externally.40

Nuh al-Tahir and the intellectual project made for his patron; Caliph Ahmad Lobbo of Hamdallaye.

Nuh al-Tahir was born in the 1770s, he travelled across west Africa for his education moving as far as Sokoto (an empire in northern Nigeria) where he was acquainted with Uthman fodio (founder of the Sokoto caliphate) he then moved to the town of Arawan, north of Timbuktu, where he was acquainted with the Kunta (a family of wealthy merchants and prominent scholars in the region), he later joined the scholarly community of the city of Djenne as a teacher thereafter joined Ahmad Lobbo's political-religious reform movement for which he was rewarded, becoming the leader of the great council of 100 scholars that ruled the Hamdallaye caliphate with Ahmad lobbo, selecting provincial rulers, mediating disputes and regulating the empire’s education system and his surviving works indicate he was a highly learned scholar41 Ahamd Lobbo was born in 1771 near Ténenkou in central Mali, he studied mostly in his region of birth and later established himself just outside Djenne where he became an influential scholar42 He maintained close correspondence with Uthman Fodio and his Sokoto empire, the latter was part of the growing revolution movements sweeping across west africa in the late 18th and early 19th century that saw the overthrow of several old states ruled by warrior elites and patrimonial dynasties that were replaced by the largely theocratic states headed by clerics.43 Its from Sokoto that Lobbo drew his inspiration and he likely also requested a flag from Uthman Fodio as a pledge of allegiance to the latter's authority (although Lobbo’s success in establishing his own state in the region would later affirm his independence from the Sokoto movement).44 Lobbo agitated for reform from the region’s established authorities: the Segu empire’s rulers and the Fulani nobility who controlled a state north of segu and the Djenne scholars, he gathered a crowd of followers and the clashes with the authorities over his teachings eventually resulted in all out war , this culminated in a battle in 1818 where he defeated the coalition of Segu, Fulani and Djenne forces, and established his empire which stretched from Djenne to Timbuktu and founded his capital in 1821 at Hamdallaye. he then expanded north to defeat the Tuareg army and seize Timbuktu in 1825.45 Lobbo’s newly founded empire was constantly at war to its west and south especially against the state of Kaarta as well as the empire of Segu46, and his independence was also denied by the Sokoto caliphate whose rulers claimed that his initial allegiance to Uthman Fodio effectively made Hamdallaye another province of Sokoto, but Lobbo contested these claims strongly, writing a number of missives in response to Sokoto’s demands for him to renew his allegiance, he cited various medieval Islamic scholars in his letters to Sokoto, especially on matters of politics claiming that his empire’s distance from Sokoto made the latter’s claim over Hamdallaye as fictional as if it were to claim al-Andalus (Muslim Spain), Lobbo aslo enlisted the support of the Kunta clerics and set his own ulama of Hamdallaye in direct opposition to that of the Sokoto ulama (west-africa’s intellectual landscape was characterized by a multiplicity of competing scholarly communities). The relationship between the two powers oscillated throughout the 1820s and 30s between periods of cordial association and episodes of tensions, Lobbo would later on not only assert his independence but in a complete reversal, now demanded the Sokoto rulers to pledge allegiance to him as their caliph. The first of these requests was made in the heat of the succession disputes that followed death of the Sokoto caliph Muhammad Bello in 1837, Lobbo made a second similar request in 1841, asking that the Sokoto ruler Abubakar Atiku (r.1837-1842) to pledge allegiance to him and accept his Lobbo’s authority as caliph, but Atiku consulted his ulama and this request was rejected with a lengthy and meticulously written reply from Sokoto’s most prominent scholar named Dan tafa, the latter castigated both Lobbo and Nuh al-Tahir (whom he mentioned in person), saying that their request of allegiance was "an issue of sin because you are asking them to be disobedient and break allegiance with their imam"47 it was in this context of Hamdallaye’s contested legitimacy that the Tarikh al-fattash was composed.

ruined sections of the original 5.6km long wall that enclosed the 2.4 sq km city of Hamdallaye, Mali

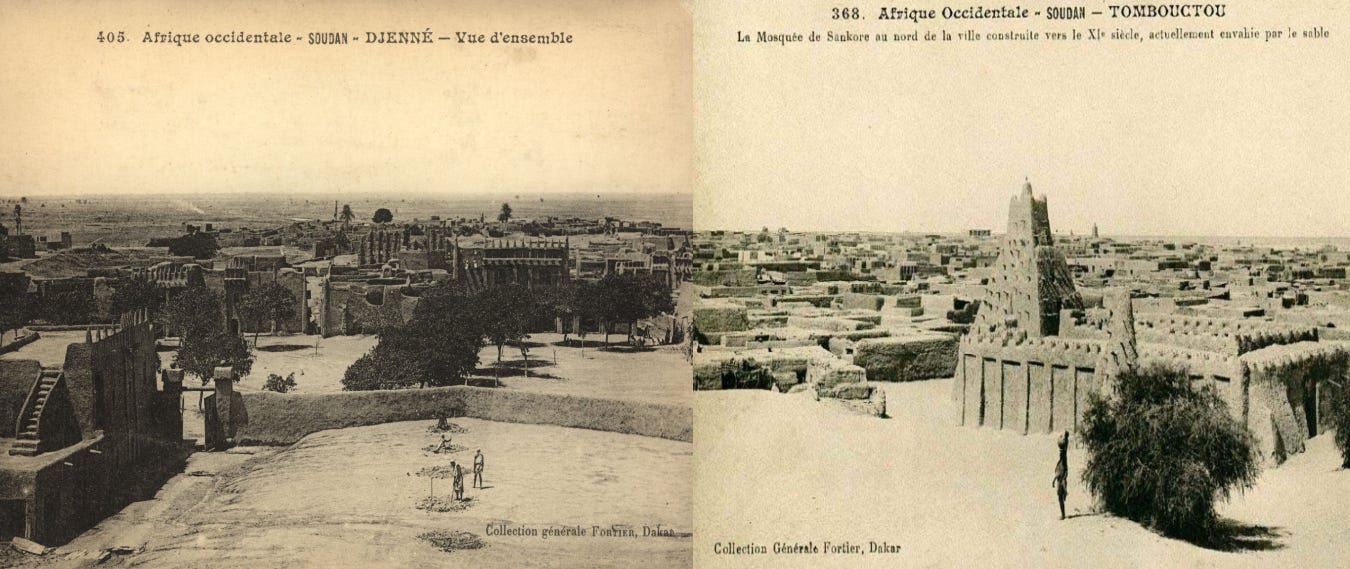

The cities of Djenne and Timbuktu in the 1906

In 19th century West Africa the significance of the terms “caliph” and “caliphate” lay in both terms' rejection of the secular term Malik ( i.e. “king”),48 the west african social and religious landscape was a world with saints, prophecies, and eschatological expectations circulating among both the learned elite and non-literate populations who expected the arrival of various millenarian figures in Islam such as the 12th caliph, the Mahdi and the Mujaddid, prominent leaders of the era attimes encouraged these beliefs inorder to augment their authority, entire communities moved east because that's where the Madhi was expected to emerge and many scholars wrote refutations against the claims of several personalities that referred to themselves as Mahdi who popped up across the region in the 19th century, the most spectacular of these millenarian movements occurred in what is now modern Sudan, where a Nubian Muslim named Muhammad Ahmad claimed he was the Mahdi and flushed the Anglo-Egyptian colonizers out of the region, establishing the “Mahdiyya” empire of sudan49. Therefore the authority of Ahmad Lobbo, as with most west african rulers of the time, rested on a network of claims that were political as well as religious in nature and he proceeded to tap into the circulating millenarian expectations as one way to legitimize his authority along with claims of the ruler’s scholarly knowledge, sainthood, and divine investiture. the Tarıkh al-fattash portrays Ahmad Lobbo as Sultan, the authoritative ruler of West Africa, and the last of a long line of legitimate rulers modeled on Askiyà Muhammad (the most famous of the emperors of the Songhay); it also portrays Lobbo as the 12th of the caliphs under whom the Islamic community would thrive (according to a hadith ascribed to the Prophet muhammad); and also claims that Lobbo was the Mujaddid (the “renewer” of Islam, who is sent by God to prevent the Muslim community going astray").50

Circulation, reception, critique and support of the Tarikh al-Fattash across west Africa

Nuh al-Tahir's ambitious project; the Tarikh al-Fattash, was put to work immediately after its composition when it made its first appearance (likely in the abovementioned request of allegiance made by Lobbo to Sokoto in 1841), while the chronicle itself wasn't circulated in its entirety, Nuh al-Tahir wrote a shorter manuscript titled Risala fi zuhur -khalifa al-thani (letter on the appearance of the 12th caliph) summarizing the Tarikh al-fattash’s central arguments, and its this Risala that is arguably one of west africa's most widely reproduced texts appearing in many libraries across the region with dozens of copies found across the cities and libraries of Mauritania and Mali. In the Risala, Nuh al-Tahir cites the authority of Mahmud Kati's scholarship (whom he claims was the sole author of the original Tarikh al-fattash in the 16th century) and his prophesies about Ahmad Lobbo on his status as caliph, Nuh al-Tahir addressed this Risala to various North african and west african rulers and ulamas including: the senegambia region of the Trarza kingdom, the southern Mauritanian towns of Tichitt, Walata and Wadan; the Moroccan sultanate and its domains in Fez and Marakesh; the Ottoman Pashas of Tunis, Algiers and Egypt; and to various unnamed regions of west africa (excluding Sokoto). This manuscript (like most documents in west Africa intended for a pubic audience) was read out loud at pubic gatherings and the information in it was widely disseminated, as the author himself encouraged all who received the letter to copy it and pass it on.51 The intellectual milieu which required and enabled west-African leaders to legitimize their claims of authority in writing was a product of centuries of growth in the robustness of west Africa's scholary tradition in which literature became an important tool not just for governance but for accessing power itself, this was especially true for the revolutionary states like Hamdallaye in which provincial rulers, councilors, and all government offices could only be attained after a candidate had reached an acceptable level of scholarship determined by his peers in the great council of 100.52

Reception of the Tarikh al-fattash was mixed but in Sokoto its claims were rejected outright by the ulama. The sharpest refutation against Nuh al-Tahir's claims came from Abd al-Qadir al-Turudi (the abovementioned Dan Tafa; born 1804 - died.1864), this eminent scholar was a philosopher, geographer and historian was highly educated in various disciplines and wrote on a wide range of subjects including statecraft. Dan Tafa’s meticulous and eloquently written response rejected the claims made by Nuh al -ahir, using the same works of al-Suyuti that Nuh al-Tahir had employed, he rejected the claim that Lobbo was the expected caliph on grounds that the last caliph would be a Mahdi (a claim which Nuh wasn't asserting for Lobbo), he rejected the claim that Lobbo could be the Mujaddid because Lobbo's movement didn’t emerge in the 12th century A.H (ie: 1699-1785 AD) which was when he would have been expected, he also rejected Nuh al-Tahir's connections between Askiya Muhammad and Ahmad Lobbo saying that the bestowal of the caliph status to the Askiya couldn't be transferred to Lobbo53. Lobbo’s claims were also rejected in the communities in the highly contested region of the Niger bend (Timbuktu and its northern environs) which had been changing hands between the forces of Hamdallaye and the forces of the Tuaregs. However in the regions of Walata and Tichitt, and much of the western sahel, claims of Ahmad Lobbo's status were accepted and some leaders paid allegiance to him, recognizing him as Caliph54.

The ancient city of walata and the ruins of the city of wadan, both in southern Mauritania

The collapse of an intellectual project, and the resurfacing of the chronicle of the researcher.

The Tarikh al-Fattash was an ambitious project, but just like the Tarikh genre from which it drew its inspiration, its death knell was the passing of Ahmad Lobbo in 1845, which happened soon after its circulation, as well as the decline of Hamdallaye under his successors which effectively rendered its grand claims obsolete, culminating in the fall of the empire to the forces of Umar Tal in 1862, and unlike the Kebra negast that was soon appropriated by later conquerors, the Tarikh al-fattash wasn’t of much importance to Umar Tal who relied on other forms of legitimacy, copies of it taken from the Hamdallaye libraries were added to the collection of manuscripts in Umar’s library at the city of Segu (after his conquest of the Segu empire as well), the collections in Umar’s library were later seized by the French forces in 1892 during the conquest of Segu, other copies of the Tarikh al-Fattash in Timbuktu were collected by the French for the colonial government (ostensibly to assist in pacifying the colony) and deposited in various institutions in the colony. All who initially encountered the Tarikh al-Fattash immediately pointed out the propagandist nature of its themes which its author made on behalf of his patron Amhad Lobbo, but the various folios of it were collected in different parts and some of these parts came to include folios that belonged to a different manuscript entirely: the 17th century chronicle Tarikh ibn al-Mukhtar, in 1913, the French translators Houdas and Delafosse combined the two under the title La chronique du chercheur and the majority of the present copies of the Tarikh al-Fattash have been derived from it.55

folios of the folio from the 19th century Tārīkh al-Fattāsh, from the Mamma Haidara Commemorative Library, Timbuktu, Mali

Copy of the 17th century Tarikh Ibn al-Mukhtar at the Bibliothèque Nationale de France (shelmark MS B/BnF 6651)

Conclusion : the power of the written word in pre-colonial Africa’s politics.

An analysis of these two documents reveals the robustness of African literally productions that were actively created, manipulated and reproduced to legitimize power using concepts and traditions understood by both rulers and their subjects, and mediated through religion and scholarship, as Munro-Hay writes: “the written word has enormous power. It can be produced with a flourish as material evidence when necessary. The older it grows, the more venerable, even if modern textual criticism can often result in an entirely different story. An old book, claiming even older origins via exotic places and languages, and written, allegedly, by authors of revered status, gains ever more respect"56 The circumstances around the composition of both the Kebra nagast and Tarikh al-fattash and their supposed disappearance and recovery was deliberately shrouded in myth and given an aura of the unattainable, the scholars credited for their composition were men of high repute, and both document’s bold retelling of themes found in religions that were “external” to their region, show the extent to which Christianity and Islam were fully “indigenised” by Africans who adopted both religions on their own terms and established them within their states as truly African institutions. In the case of the Kebra nagast; its much older age , its firmer collaboration with an even older religious institution of the 1700yr old Ethiopian orthodox church (including claims of possessing the “Ark of the convenant”), its existence in an a state whose intellectual traditions weren’t characterized by multiplicity (and its claims could thus not be challenged) and the continuity of the Ethiopian empire for 700 years guaranteed its longevity, authenticity and popularity as arguably the most widely known African epic, which eventually inspired religious movements such as Rastafarianism.

Historians have previously interpreted these texts in a way that is devoid of their authors intent, seeing them as caché of historical information instead of engaging them as complex discourses of power. While such “cachés of historical facts and information” exist in Africa’s intellectual traditions such as the dozens of royal chronicles written by the Ethiopian emperors, and the dozens of west african chronicles written by many scribes including the Tarikh ibn al-mukhtar, the search for historical information mustn't disregard the political context that dictated their composition with their precise rhetorical plans and authorial intentions.57 In the quest for the “original” old chronicles, historians ignore later additions as mere forgeries that corrupted the transmition of historical information and this ultimately leads them to create an incomplete picture of the African past. These chronicles weren't simply repositories of hard facts that their authors where hoping to relay to a future researcher, but were creative reconstructions of the past dictated by the political-ideological exigencies of their time.

for more on African history and to download some of the books cited in this article, subscribe to my Patreon account

The Ark of the Covenant by Stuart Munro-Hay pg 19, 80-81, 84-85)

The Ark of the Covenant by Stuart Munro-Hay pg 182

The Ark of the Covenant by Stuart Munro-Hay pg 18-19)

The Apocryphal Legitimation of a “Solomonic” Dynasty in the Kǝbrä nägäśt by Pierluigi Piovanelli pg 17-18, The Ark of the Covenant by Stuart Munro-Hay pg 63-66

The Ark of the Covenant by Stuart Munro-Hay pg 23)

Church and State in Ethiopia by Taddesse Tamrat 1972: 72–74)

The Apocryphal Legitimation of a “Solomonic” Dynasty in the Kǝbrä nägäśt by Pierluigi Piovanelli pg 9, The Ark of the Covenant by Stuart Munro-Hay pg 207)

The Ark of the Covenant by Stuart Munro-Hay pg129-130)

The Ark of the Covenant by Stuart Munro-Hay pg 205)

The Ark of the Covenant by Stuart Munro-Hay pg 183)

The Ark of the Covenant by Stuart Munro-Hay pg186)

How the Ethiopian Changed His Skin by D Selden pg 339-340, Aksum and nubia by G. Hatke pgs 94-97, 52-53

Foundations of an African Civilisation by D. W Phillipson pg 84

Foundations of an African Civilisation by D. W Phillipson pg 26-39

The Ark of the Covenant by Stuart Munro-Hay pg 51

The Ark of the Covenant by Stuart Munro-Hay 76-77)

The Ark of the Covenant by Stuart Munro-Hay pg 183-184)

The Ark of the Covenant by Stuart Munro-Hay pg 66, 86

The Ark of the Covenant by Stuart Munro-Hay pg 91

Church and State in Ethiopia by Taddesse Tamrat pg 206-248

The Ark of the Covenant by Stuart Munro-Hay pg p 108-109)

The Ark of the Covenant by Stuart Munro-Hay pg 113)

The Ark of the Covenant by Stuart Munro-Hay pg 114)

The Ark of the Covenant by Stuart Munro-Hay pg 115),

The Ark of the Covenant by Stuart Munro-Hay pg 127)

The Ark of the Covenant by Stuart Munro-Hay pg 183)

The Ark of the Covenant by Stuart Munro-Hay pg 140)

The Ark of the Covenant by Stuart Munro-Hay pg 187)

The Ark of the Covenant by Stuart Munro-Hay pg 120)

The Ark of the Covenant by Stuart Munro-Hay 182

The Apocryphal Legitimation of a “Solomonic” Dynasty in the Kǝbrä nägäśt by Pierluigi Piovanelli g 11-12

The Ark of the Covenant by Stuart Munro-Hay 182 85)

Sultan, Caliph, and the Renewer of the Faith by Mauro Nobili pg 58-70)

The meanings of timbuktu by Shamil Jeppie pg 104-105)

Sultan, Caliph, and the Renewer of the Faith by Mauro Nobili 94-95)

Sultan, Caliph, and the Renewer of the Faith by Mauro Nobili pg 80-82, 103-4, 108)

Sultan, Caliph, and the Renewer of the Faith by Mauro Nobili pg 101)

Sultan, Caliph, and the Renewer of the Faith by Mauro Nobili 105-106)

Sultan, Caliph, and the Renewer of the Faith by Mauro Nobili pg 111-112)

Timbuktu and the Songhay Empire by John Hunwick pgs 105-106

Sultan, Caliph, and the Renewer of the Faith by Mauro Nobili pg 84-88)

Sultan, Caliph, and the Renewer of the Faith by Mauro Nobili pg 132-135)

Sultan, Caliph, and the Renewer of the Faith by Mauro Nobili pg 15-16)

Sultan, Caliph, and the Renewer of the Faith by Mauro Nobili pg 136-7, 184)

Sultan, Caliph, and the Renewer of the Faith by Mauro Nobili pg 157-158)

Sultan, Caliph, and the Renewer of the Faith by Mauro Nobili pg 11-13)

Sultan, Caliph, and the Renewer of the Faith by Mauro Nobili pg183-199)

Sultan, Caliph, and the Renewer of the Faith by Mauro Nobili pg 7)

Sultan, Caliph, and the Renewer of the Faith by Mauro Nobili pg 228-230)

Sultan, Caliph, and the Renewer of the Faith by Mauro Nobili pg 24-25)

Sultan, Caliph, and the Renewer of the Faith by Mauro Nobili pg 208-211)

Sultan, Caliph, and the Renewer of the Faith by Mauro Nobili pg 213)

Sultan, Caliph, and the Renewer of the Faith by Mauro Nobili pg 220-222)

Sultan, Caliph, and the Renewer of the Faith by Mauro Nobili pg 223-225)

Sultan, Caliph, and the Renewer of the Faith by Mauro Nobili pg 52-57

The Ark of the Covenant by Stuart Munro-Hay pg 182)

Sultan, Caliph, and the Renewer of the Faith by Mauro Nobili pg pg 29-30)