The pyramids of ancient Nubia and Meroe: death on the Nile and the mortuary architecture of Kush

a complete history of an African monument

Sudan is home to the world’s highest number of pyramids —the legacy of the kingdom of Kush, which undertook one of the most ambitious building programs of the ancient world. More than 200 pyramids spread over half a dozen cities were built by the rulers and officials of Kush over a period of 1,000 years.

These grand monuments were the product of centuries of development in the mortuary architecture of ancient Nubia. Their architectural antecedents were set in the bronze-age kingdom of Kerma, their appearance was refined during the New Kingdom era, and their tradition was fully established by the pyramid builders of Kush at their capital in Napata, from where they ruled Egypt and Nubia.

This article provides a complete history of the pyramids of Kush. It outlines the mortuary architecture, religion and cultural practices of the people who lived in ancient Nubia, from their origin at Kerma to their zenith at Meroe.

Map showing Kush at its height in the 7th century BC

Support AfricanHistoryExtra by becoming a member of our Patreon community, subscribe here to read more about African history, download free books, and keep this newsletter free for all:

Antecedents of ancient Nubia's funerary architecture: the mortuary religion of Bronze-age Nubia: 3700BC-1500BC

The largest among the early states which controlled ancient Nubia was the kingdom of Kerma. Known in external texts as the kingdom Kush, its history has been primarily reconstructed from the archeological studies at its largest cities of Kerma and Dokki Gel.

The capital of Kerma was an agglomeration of settlements with palatial, defensive, administrative, domestic, and religious buildings since around 2400BC. Entire quarters in both Kerma and the ceremonial city of Dokki Gel were established for religious purposes, such as the religious precinct near the massive temple of 'Western Deffufa', and the secondary urban complex. These religious settlements featured temples, chapels, and ecclesiastical workshops for preparing offerings for cult installations, all built with stone and mudbrick, accessed via processional avenues, and located near the palaces and temples.1

Kerma's religion featured ancestral veneration where the world of the dead reproduced the hierarchy that existed among the living. This is evidenced not just by its temples dedicated to both chthonic and solar deities, and their associated chapels and workshops to commemorate its rulers, but also by the monumental tumuli tombs in the city's royal necropolis with over 3,000 tombs, and where elaborate mortuary rituals were practiced.2

The largest Kerma tombs spanned 90 meters and contained over 5,000 sacrificial cows and luxury grave goods. They were had large circular superstructures that covered vaulted burial chambers, accessed through corridors and descendary staircases from the chapels attached outside where where funerary offerings were left. The dead were placed in contracted position on wood-and-leather beds of elaborate faunal designs, and the tomb was surmounted with stone stela placed at the roof terrace that was accessed via a staircase.3

Besides the kingdom of Kerma, the mortuary practices and religions of other early Nubian states anteceded those which emerged in Meroitic Kush. The earliest of these states was the A-Group chiefdom (ca 3700–2800BC) located in lower Nubia. A-Group royal tombs featured large tumuli that covered rich burials containing large numbers of sacrificial animals, and attached to the tombs were offering places. A-Group mortuary practices were most likely a continuation of the religious conceptions formed in the shared cultural milieu of the ancient Nile valley civilizations, that are first attested at the prehistoric site of Nabta Playa (c. 5100–4700BC) where similar tumuli tombs with rich burial chambers were found.4

The A-Group chiefdom was succeeded in lower Nubia by the C-Group chiefdom (ca. 2300BC-1550BC), which created featured an even more elaborate mortuary practice than its predecessor. C-group graves, especially at Aniba, included stone stelea and round tumuli superstructures covering rich burial chambers that were accessed through mud-brick chapels. During its later phases, the C-Group chiefdom was conquered by the Kerma kingdom which was expanding into Egypt in the 17th century BC. The chiefdom's mortuary architecture reflected Kerma influences, with large tumuli, stone chapels, vaulted mud-brick chambers, bed burials and the burial of rams.5

Kerma; the royal tomb during excavation, and a reconstruction of the superstructure of the royal tomb, photo and illustration by C.Bonnet

Stelae and stone rings in Cemetery N at Aniba, C-Group chiefdom, photo by Steindorff

It was the above mortuary religions and practices in the ancient Nubian kingdoms that would be gradually modified over several centuries as the kingdoms of Kush and Egypt interacted and expanded. While Kerma kings didn’t build pyramids, they built all the essential features of Nubian mortuary architecture (chapels, descendary, roomed burial chambers, stelae, and superstructure) that would be slightly modified by later tomb-builders who changed the circular superstructure to the right-angled pyramid.

The introduction and disappearance of pyramid tombs in Nubia during the New kingdom period. (1500BC-1100BC)

After nearly a century of Kerma's expansion into southern Egypt, the reconstituted state of 'New kingdom' Egypt reversed the equilibrium of power in the Nile valley and expanded south into Kerma, subduing it after several decades of war. It's during the New kingdom era in Nubia that the earliest pyramid structures appeared on tombs to replace the circular tumuli, and these were constructed by Nubian "princes" as well as appointed officials from Egypt. While Egyptian kingship had since abandoned pyramid-building for over 8 centuries, the custom was revived by the Nubians and Egyptians active in New kingdom Nubia's administration.

These Nubian "princes" were taken from the pre-existing dynasties of the chiefdoms that constituted the C-Group state (Wawat in lower Nubia) and the Kerma state (Kush in upper Nubia). One of these pre-existing chiefdoms named Tehkhet had its capital at Serra and Debeira, where atleast 4 of its princes were buried in monumental structures that show a clear transition from the tumulus types of the C-group to the steep pyramid. Most notable among these graves were the mud-brick pyramids of Djehuty-hotep and Amenemhet in Debeira East.6

Besides Debeira, other pyramid burials were attested at Aniba, where the viceroy of lower Nubia lived; also at Soleb which was the center of a royal cult, and at Tombos, where a small mudbrick pyramids were erected for an official named Siamun.7

This was part of the larger processes intended to unite the Nubian and Egyptian sacred geographies, through syncretizing Nubian religious practices, deities and ideologies of power with Egyptian ones. Its best evidenced by the transformation of the pre-existing Nubian ram-gods into Nubian Amun-deities with temple-cults, and the adoption of the Nubian gods like Dedwen into the Egyptian pantheon.8

Map of the middle Nile region showing the pyramid sites of new kingdom nubia

However, the construction of these pyramids and the general participation in Egyptian-temple institutions by the Nubian administrators of the New kingdom era remained confined mostly to Lower Nubia, and even then only among the elite. Most of the pre-existing Nubian institutions were preserved especially in Upper Nubia, and the region’s mortuary cults and other religious practices survived, as attested by the non-Egyptian mortuary rites and tumulus graves of the region.9

During the 20th dynasty, the Egyptians withdrew from Upper Nubia in the reign of Rameses IX (1125–1107BC) and Lower Nubia during the reign of Rameses XI (1098–1069BC). As central control collapsed, local authority and religion were fully reestablished by the Nubians as Egyptian temples with their associated cults were left to ruin.10

The last pyramid of Lower Nubia during the New Kingdom era was built by Panehesy (“the Nubian”) at his capital in Aniba. Panehesy had been appointed viceroy of lower Nubia by Rameses XI but later rebelled and ruled the region until his death. Panehesy’s pyramid grave at Aniba is a telling document of his authority in Lower Nubia, and represents the site's continued cultural importance since it first emerged during the C-group chiefdom.11

Aniba, Pyramidal superstructure of tomb SA34, mud-brick chapel of tomb S3112

The pyramid tradition of New kingdom Nubia ended with the collapse of the Egyptian administration. Whatever its intended political function was, whether by the Nubian princes or by the Egyptian officials, would have been lost to the independent rulers who took over the region and discontinued the building of pyramid graves. The tradition’s re-emergence by the kings of Kush at el-Kurru would therefore follow different prerogatives.

The genesis of the Pyramid tombs of Kush: a chiefdom at el-kurru and the Napatan era of Kush. (9th-4th century BC)

Over a period of three centuries, the fragmented local polities of upper Nubia gradually grew into larger chiefdoms, the biggest of which had its capital at el-Kurru in Sudan around the 10th-9th century BC from where it expanded into lower Nubia and 4th cataract region. The rulers of el-Kurru buried in the tombs labeled (Ku. 2-6) syncretized various Nubian mortuary practices as part of a politically driven process of integrating pre-existing Nubian polities. They combined the circular stone superstructure and contracted body of the C-group type burials, with the bed-burials of the Kerma kingdom, and the pit-and-side-chamber substructure of their el-Kurru population.13

These el-Kurru rulers eventually revived the long-distance routes across north-east Africa, and initiated contacts with the then-divided Egypt through the latter's southern capital of Thebes. It's through these contacts that the el-Kurru rulers (especially beginning with Ku. 6's owner; king Aqomaloye) fused aspects of their syncretized Nubian religion with contemporary Egyptian religion. This is first attested to by the smashing of funeral vessels; a funerary rite which had been abandoned in Egypt but revived by the Nubians of el-Kurru. Aqomaloye's tomb also shows the transition from tumuli tombs to early pyramid-type tombs, as it contains a mortuary cult chapel enclosed within a walled precinct.14

The revival of pyramid building was gradually accomplished by succeeding rulers. The king buried in Ku. 13 built a round tumulus-on-mastaba tomb, while his successor at Ku. 14 built a steep angled pyramid-on-mastaba. The mortuary architecture of el-Kurru was likely influenced by contemporaneous mortuary architecture at Debeira in lower Nubia, where both tumuli burials were being built (and also where the old pyramid burials of New-kingdom era Nubian princes were located).15

This transformation profoundly altered the mortuary cult of the royal ancestors, and was adopted by the el-kurru rulers to create a unique kingship ideology. The el-kurru rulers appropriated the prerogatives of their Nubian (Kerma) and (new kingdom) Egyptian predecessors, to create a concept of continuity with the past and legitimate their expansionism, initially over Nubia and later over Egypt as the 25th dynasty.16

The later pyramids at el-Kurru, such as Ku. 9 and Ku. 8, belonged to king Alara and his successor Kashta, both of whom reigned in the 8th century and are mentioned by their successors as the direct ancestors the kings of Kush. Their pyramid tombs have fully developed architectural features modeled on his predecessors. Both tombs are the first to be provided with inscribed mortuary stela and an offering table. Alara revived the royal cult of Amun of Napata, who was considered a local, self-standing Nubian deity residing at Gebel-Barkal (Napata), and whose character was inherited his role and features from the ram-cults of Kerma.17

The revival of the Nubian Amun cults and their related temple and mortuary cults, provided the theological legitimacy for Alaras' successors Kashta and Piye to conquer Egypt, and continue to syncretize Nubian and Egyptian mortuary practices with the first real pyramid built by Piye at Ku. 17.18

The cemetery at el-Kurru showing the gradual development from a tumulus to a mastaba and to a pyramid. The main part of the cemetery at el-Kurru, showing the earliest burials 1-6, and the pyramid burials, of Piye (17), Shabaqo (15), and Tanwetamani (16) and Shebitqo (18).

The royal pyramids of el-Kurru

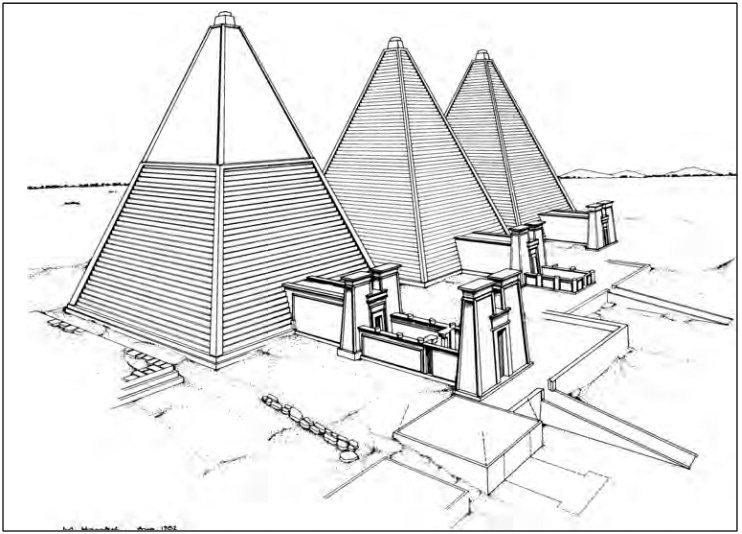

Fully developed at el-Kurru, the royal cemetery was moved to Nuri (opposite Napata) by Taharqo in 664, then to Jebel Barkal (south of Napata) around the 4th century BC during the reign of Aktisanes and finally to Meroe under the reign of Arkamani I in the 3rd century BC. The mummified bodies of Kush's royals were interred in sarcophagi placed on beds in richly painted funerary chambers, with grave material (shawabti, inscribed stelae, offering tables) in multi-chambered sub-structures surmounted by a pyramid superstructure, accessed through an attached chapel and forecourt.19

These pyramids had a steep-sided 60-70 degree slope first attested at el-Kurru, with an average size of 27.50/27.90 by 27.50/27.90 meters, and a height of 30 meters, save for Taharqo's 50-meter high pyramid at Nuri. The pyramids were often erected after the burial of the deceased ruler had been sealed by his successor, save for a few exceptions built by reigning kings. Radical shifts in pyramid sites were often associated with political and dynastic changes, eg the unnamed king of the 4th century BC buried at the large pyramid Ku. 1 instead of at Nuri like his predecessors or the pyramid of Arkamani I at Meroe who established a new dynasty. But minor changes in pyramid sites were made after the original necropolis was filled eg Aktisanes's move to Jebel Barkal.20

The nuri royal pyramids

The royal pyramids of Jebel Barkal

Initially the preserve of royals of the Kushite kings, the pyramid became a common marker of elite burials around the capital (Napata) and throughout the kingdom. The monument progressively appeared on the graves of non-ruling royal in the cemeteries of the main administrative centers of the kingdom. By the end of the Napatan period and for the entirety of the Meroitic period, the multiplication of pyramids profoundly transformed the religious landscape of Nubia.21

The construction of such pyramids is attested at Sedeinga during the late Napatan era. These were often small constructions using mudbricks instead of stone, and built exclusively for children whose adults were buried in stone pyramids. Despite the ubiquity of pyramid-tombs, the non-elite population of Kush retained the classic tumulus graves. These were constructions consisted an oval-shaped mound covered with a mudbrick dome.22

The Sedeinga necropolis showing both pyramid-graves and tumulus graves

It was therefore during the Napatan era that the pyramid tradition of Kush was established beginning at el-kurru, and would be continuously practiced by the rulers and officials of Kush until the kingdom’s decline.

Map of the middle Nile showing the pyramid sites of Kush during the Napatan and Meroitic eras

The pyramids of the Meroitic kingdom of Kush and Kushite mortuary religion.

The royal mortuary architecture of Meroe followed established traditions of the preceding Napatan era. Studies of the pyramid-tombs reveal aspects of the political history of Kush, its mortuary religion, the function of the Meroitic writing system, the domestic industries of Kush, and its scientific traditions. The multiplication of these funerary structures was a result of the democratization of Kush's social institutions during the Meroitic period, corresponding with the broader change brought by the emergence of the new dynasty.

Around 275BC, king Arkamaniqo overthrew the Napatan dynasty which had been ruling Kush for the five preceding centuries, and established his own dynasty that originated from the Butana region of Meroe. Known as Ergamanes in external accounts, Arkamaniqo's adoption of a usurping king's throne-name hints at the violent circumstances in which his new 'Meroitic' dynasty emerged.23

The new dynasty stressed its connections with the region of the City of Meroe by transferring the royal burial ground from Napata to Meroe, beginning with Arkamaniqo's pyramid at Beg. S. 6. Their ascendance heralded a reformulation of the Kushite state, the re-emergence of the cults of Nubian deities and the re-interpretation the Napatan era's architectural and artistic styles.24

The imagery carved on Meroitic Pyramids also reveals the salient features of Meroitic institutions. These include the organization of the royal court as shown by the composition of the mortuary procession, the Meroitic kingship dogma as shown by the iconography of royal regalia, the nature of royal succession as shown by the relatives placed near the seated ruler, and the relationship between the Royals and provincial governors shown by comparing the royal and non-royal elite pyramids outside the capital.25

The extensive use of cursive Meroitic script in Kush's pyramids and mortuary practices was a result of the tacit agreement between the royal and non-royal authorities regarding the use of former royal prerogatives in funerary contexts. The cursive script was, like the Meroitic hieroglyphic, initially used exclusively by royals in their own mortuary cult, before it was used by non-ruling royals and later by non-royal elites. Literacy was thus no longer exclusively associated with kingship as it now functioned as the decorum of the non-royal elite, the provincial elite, the priesthood of all ranks, local administrators, their wives and children.26

The Meroitic Mortuary cult

The Meroitic cult of the dead is mostly known through the pyramidal monuments, funerary chapels, and their associated liturgical material. Pyramid images displayed the essential mortuary cult of Kush including the donation and consecration of funerary offerings, and the inauguration of the deceased's ancestor cult as witnessed by the procession of priests and relatives. The Meroitic narrative for the deceased's death and rebirth in the afterlife was noticeably transformed from the Napatan era when the Osirian myth was first adopted in Kush.27

The Ritual scenes and texts to sustain the owner’s afterlife were executed in low relief on the interior of the pyramid's chapels, and were covered with plaster and painted in bright colors including using gold leaf to depict jewelry. These Images recorded the preparation and performance of funerary offering rites in which foodstuffs of many kinds -especially drink libations, were prepared and offered.28

Among the deities depicted in the chapel reliefs was Anubis, Isis and Nephthys, who are responsible for offerings, while Thoth recorded and declared them on behalf of the seated tomb owner who watched these activities. Since the pyramids were oriented to the cardinal compass points, ritual scenes and funerary objects in these east-facing chapels were illuminated by 'life-giving rays' of the rising sun.29

The west walls of the royal pyramids had a niche for a stela of the deceased, and the niche was also surmounted by a scene of the day-bark in which the transfigured tomb owner traveled across the heavens in the company of the sun god Ra.30

The deceased person who was commemorated and remembered through their pyramid monument and inscription, could thus become an approachable intercessor between the realm of the gods and the living world.

Queen Shanakadakheto’s pyramid Beg. N 11, eastern portion of north wall, showing rite of leading in the calves taken from temple scenes and the Judgment before Osiris.

Inscribed offering table of Prince Tedeken showing Nephthys and Anubis pouring libations on altar with fruits and flowers, Beg W. 19, 200–100 B.C, Boston Museum of fine Arts, No. 23.873

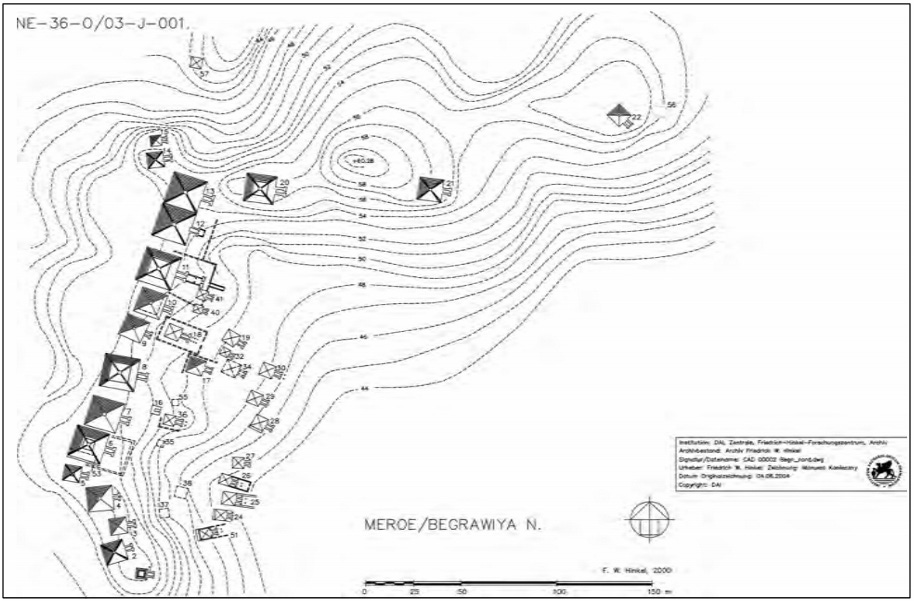

Arrangement of the royal pyramid-complexes around Meroe

There were three main Royal necropolises around the city of Meroe, the Southern cemetery, the Northern cemetery, and the Western cemetery. The Southern Cemetery was chosen for the first royal burials at Meroe after the ascendance of the Meroitic dynasty, while the Western Cemetery became the burial ground for non-ruling members of the royal family, and when the Southern cemetery filled, the Northern Cemetery was opened to its north.31

The western cemetery is the oldest and largest of the three royal necropolis complexes at Meroe. It had been used to bury both the residents of Meroe and the non-ruling royals of Kush since the 9th century BC, when the city was gradually incorporated into the expanding Napatan kingdom of Kush.32

It contains over 800 graves of which 171 had pyramid superstructures dating from the Meroitic era, among which are 82 pyramids while the rest are indeterminate. The cemetery was home to the burials of non-ruling Meroitic queens, princes, and members of the extended family, the latter of whom attimes squeezed their pyramid graves next to the pyramid of their deceased relative, in a practice used across all cemeteries of Kush.33

Meroe, Plan of Western Royal Cemetery, map by Dunham

Meroe, the Western Cemetery, photo by Carsten ten Brink

The southern cemetery was first used around the 8th century BC to bury residents of Meroe, before it was turned into the Royal cemetery of Meroitic rulers. It contains 220 burials including 90 with superstructures, of which atleast 24 were pyramids. The first pyramids belong to non-ruling royals buried during the transition between the late Napatan and early Meroitic period, before King Arkamaniqo officially moved the royal necropolis from Napata (Jebel Barkal) to Meroe.34

Meroe, The Southern Royal Cemetery, map by Dunham

Meroë Pyramids, Southern Cemetery, photo by tobeytravels

The Northern Cemetery was first used around the 3rd century for burying the Queen-consorts of the Meroitic kings buried in the southern cemetery, before it too became home to the pyramids of the ruling Kings and Queens of Kush after the southern cemetery became overcrowded. It contains 41 pyramids belonging to 30 kings, 8 Queen-regnants, and 3 crown princes. The largest of these pyramids, whose style was followed by its successors, was Beg. N. 11 measuring 26m high, belonging to Queen Shanakdakhete, the first female ruler (Kandake) of Kush (c. 170-150 BC). It had the most elaborate chapel design with two decorated forecourts in front, and its pylons were carved with large triumphal images of the ruler.35

Meroe, the Northern Royal Cemetery, map by Dunham

Meroe, northern cemetery, photo by Sophie Hay

Construction of the Meroitic pyramids and a description of their exterior and interior features.

The construction of the pyramid begun by making its architectural plan, as shown by the architectural design of a pyramid preserved on a wall of the cult chapel of pyramid Beg. N. 8, that was intended for pyramid Beg. N. 2 (King Arnanikhabale) in the middle of the AD 1st century.36

The main construction material was sandstone, quarried from the city's hinterland.37 The pyramid's outer mantle consisted of dressed sandstone blocks covering an interior built with sandstone rubble, with the exception of a few that were built entirely with sandstone blocks like their Napatan predecessors. The pyramids were built using a shaduf, an ancient lever-based lifting device used to lift water from irrigation canals.38

The exteriors of the pyramids were embellished since limestone plaster and paintings has been found on pyramids of both royal and non-royal elites. Most pyramids were crowned by capstones of various fashions that were placed on their truncated summits, in Meroe these had a circular base with two holes, probably to insert a bronze solar disk.39

architectural plan of a pyramid incised on the chapel of Beg. N. 8, interpretation of the pyramid drawing’s measurements, drawing showing the use of a shaduf in pyramid construction, illustrations by L Torok and M. Hinkel

Meroe, underground galleries and supporting pillars in quarry Q41, photo by Brigitte Cech

As many as three burial chambers were dug beneath the pyramids and accessed by a stepped descendary with a barrel vaulted roof, and cut in front of the chapel or underneath it. Once interment was completed, the doorway into the burial chambers was blocked and remnants from the final funeral ceremonies were placed in front of the blocked door and in the stairway.40

Decorated stone offering chapels completed the features shared by all Meroitic pyramids. The chapels of royal pyramids were constructed against the monument's eastern faces, and they typically had pylons on which were inscribed images of the King or Queen smiting enemies followed the established iconography appearing on Meroitic temples and palaces. The chapel served as a bridge between the deceased's grave and their living relatives; a place where rituals could be performed and prayers conveyed to the other world. Chapels held various grave materials related to the mortuary rituals including inscribed offering tables, stelae, and luxury grave goods.

The Meroitic offering tables were fashioned after those used during the Napatan era when the tradition had been revived. Their surface decoration alternates between carved and incised scenes with representations of offerings and the figural scenes where divinities perform a libation. The Meroitic offering tables were initially made for chapels of royal families, as their table scenes represented miniature versions of the extended scenes inscribed on the walls of the Kings and Queens of Kush whose large pyramid-chapels obviated their need.41

Mortuary rituals involved the pouring of libation poured on an offering table placed on a small pedestal made with mudbricks, after which the libation would overflow through an apex and spill onto the ground. Through this process, the water would magically convey the prayers and the food offerings carved on the table, directly to the dead.42

The funerary stela placed in Meroitic pyramid-chapels followed established traditions of grave stelae used in the Napatan period that had been reserved for royals but became democratised by the Meroitic elite. These meroitic stelae display a remarkable diversity, their surfaces were inscribed with texts about the deceased's lineage as well as invocations addressed to Isis and Osiris, and they contained painted/carved figural scenes representing the deceased.43

The lintels of non-royal funerary chapels were made in an archaic style, with a winged sun disc flanked by two uraeus-serpents following the established architectural traditions of most Meroitic buildings. This particular symbol legitimated the status of Meroitic elites, since its appearance on a private edifice mimics the appearance of the official temples. When decorated, the doorjambs of the chapels visually opposed the abovementioned deities Anubis and Isis or Nephthys, one on each side of the door, pouring a libation for the dead.44

Queen Shanakadakheto’s chapel and forecourt, Beg. N 11, photo by shutterstock, Reconstruction drawing of Beg. N 11 showing its pylon, two forecourts, and chapel with pylon, illustration by M. Hinkel

The interiors of pyramid graves often contained selected mortuary equipment meant to accompany the deceased through their journey to the aferlife.

The deceased's coffin or burial shroud was lain on a bed for most royals, while non-royals were placed on a funerary bench made of stone or on the floor. There seems to have been no deliberate mummification of the corpse before it was placed in its coffin, although the cadavers were often washed or scented with oils and preserved from insects with incense-like substances, and the dry desert ensured that most of the body remained intact. Meroitic coffins were based on models used during the Napatan period and must have constituted a significant local industry, alongside the cotton burial shrouds that used local textiles and were retained by the kingdoms which succeeded Kush.45

Grave goods were placed in the chapel or ontop of the body of the deceased, and they often constituted personal belongings of the deceased and the remains of the funerary banquet brought by their relatives. These included amulets of the deities Apedemak, Amun, Bes and Isis and excellently painted pottery. The fine quality Gold and silver jewelry, as well as the bracelets, armlets, shield rings and pendants richly decorated with gold wire, granulation and fused-glass inlays demonstrate the continuity of late Napatan and Meroitic goldsmith's art.46

Other ornaments were placed on the side of the body such as weapons, containers and utensils such as beautifully painted, wheel-thrown pottery ceramics. The smaller ornaments were locked in small caskets of wood such as small metallic utensils, kohl tubes and glass containers. Unfortunately, all Meroitic cemeteries were pillaged before modern excavations, the grave robbers mostly left the less valuable objects.47

Bracelet with image of Hathor from Gebel Barkal, pyramid 8, 250–100 B.C, Boston Museum of fine Arts No. 20.333, Necklace with lion heads representing Apedemak, 185–100 B.C. Boston Museum of fine Arts No. 24.488

The non-royal pyramids of Meroitic Kush.

The monumental tombs of provincial officials followed models already established by non-ruling members of the royal family. Initially showing similarities with royal models, the elite pyramids soon diverged from the royal pyramids. The pyramid chapel, its capstone, accompanying texts, and statuary gradually changed over time. In Lower Nubia, the monument came to be accompanied by an offering chapel and elaborate grave material including stele, an inscribed offering table, paintings, a ba-bird.48

The pyramid of a prince Tedeqene dated to the late 2nd century BC in the West cemetery at Meroe was the earliest to have a full panoply of funerary cult objects (offering table and stela) typically found in chapels of the ruling royals. Tedeqene's pyramid shows how the abovementioned Meroitic mortuary practices and inscription formulae that was initially associated with the royal were quickly adopted by non-royal provincial elites, not just at Meroe, but also across the kingdom in the northern territories at Karanog, Faras, Sedeinga, and Sai Island.49

Profusely inscribed and painted Stela also appear frequently in the northern territories of Kush. At sedeinga, a pyramid belonging to a provincial ruler named Natemakhora who served as the sleqene (a provincial office) of Sedeinga in the late 2nd century, was found with funerary texts carved on the stela, the lintel, and the threshold of the chapel. Such texts emphasized the rank of the deceased.50

A funerary statue called the 'ba-statue' was usually placed on top of the chapel of non-royal elites, down from their initial location at the top of the pyramid's capstone. The ba-bird was adopted from the Egyptian concept which represented is the soul of the deceased, but while the Egyptian ba figure represented a bird with a human head, the Meroitic ba was represented by a human figure with bird's wings. The design of the anthropomorphic ba-statues was influenced by the representation of the Meroitic royals depicted on the walls of palaces, and temples, first appearing on Queen Shanakadakheto royal pyramid in its bird-form, its transformation occurred in lower Nubia.51

Penn museum model of a governor’s tomb in Karanog (the site is currently lake Aswan)

Karanog ; ba statue of a winged male representing a governor of Akin, painted stela, 100-300AD, Penn museum

The non-elite tumulus tombs of Kush, and the decline of the Meroitic state

The mortuary practices of the lower stratum of Kush's society were influenced by the mortuary religion of the upper classes and Kushite theology of the learned priesthood in the cult temples who were also responsible for the purity of the performance of the mortuary rites. But non-elite funerary architecture was nevertheless quite different from royal funerary architecture, especially during the late Meroitic period, and shows a seemingly unbroken cultural continuity with the mortuary practices of ancient Nubia.52

At the site of Jebel Makbor near Meroe with about 1,000 graves, four tumuli were built in close proximity and style with each other, and their dating cuts across the span of Nubian history. With one dated to the proto-historic period, one from the Meroitic period and two from the post-Meroitic period.53

The elite tumuli at El-Hobagi, which began around the 4th century, shows that the tradition of tumuli building had never been abandoned, and would be reinstated by the rulers who succeeded the last kings buried under pyramids at Meroe.54

The kingdom of Meroe went into decline around the 4th century, as shown by the pyramid burials of the last generations which indicate signs of a rather sudden economic decline. One of the last known royal pyramids was built by Queen Amanipilade (Beg N. 25) in the middle of the 4th century, just before the Aksumite invasion of Meroe by king Ezana.55

While the central government at Meroe collapsed, new capitals sprung up across the region, especially at Qustul and Ballana which contain rich tumuli graves for the rulers of the emerging kingdom of Noubadia. The pyramid tradition which had lasted over 1,000 years in Kush, staggered on for a short while, with the non-royal pyramids of Soba-east and Gebel Adda, before it was finally abandoned.56

Like its pyramids, the kingdom of Kush was home to one of the world’s oldest and most dynamic religions. By the Meroitic era, it had a pantheon with dozens of gods and goddesses, many of which were Nubian in origin.

If you like this article, or would like to contribute to my African history website project; please support my writing via Paypal

The Black Kingdom of the Nile by Charles Bonnet pg 1-17, 22-25)

The Black Kingdom of the Nile by Charles Bonnet pg 32, 37-38, 41-43, 47, Between Two Worlds by László Török pg 141-2

The Black Kingdom of the Nile by Charles Bonnet 65-68, Between Two Worlds by László Török pg 143-144)

Between Two Worlds by László Török pg 45-46)

Between Two Worlds by László Török 64-66, 166)

Between Two Worlds by László Török pg 264-266, 268)

Wretched Kush by Stuart Tyson Smith pg 138-145, Between Two Worlds by László Török pg 280,

The Image of the Ordered World in Ancient Nubian Art by László Török pg 188)

Between Two Worlds by László Török pg 264, 282-3

The Kingdom of Kush by László Török pg 82-121

The Kingdom of Kush by László Török pg 105-107

Structures and realities of the Egyptian presence in Lower Nubia from the Middle Kingdom to the New Kingdom by Claudia Naser pg 560

Between Two Worlds by László Török 305, 311-312)

Between Two Worlds by László Török pg 306-307

Between Two Worlds by László Török pg 308- 309,

The Kingdom of Kush by László Török pg pg 117-120

Between Two Worlds by László Török pg 314-17, 250-251

The Kingdom of Kush by László Török pg 153, 165-6)

The Kingdom of Kush by László Török pg 326-327,

The Kingdom of Kush by László Török 356-357, 390, 395)

Death and Burial in the Kingdom of Meroe by Vincent Francigny pg 590

Closer to the Ancestors. Excavations of the French Mission in Sedeinga 2013-2017 by Claude Rilly and Vincent Francigny

Hellenizing Art in Ancient Nubia by László Török 13-19

Between Two Worlds by László Török pg 390-392)

The Royal and Elite Cemeteries at Meroe Janice W. Yellin pg 563

Between Two Worlds by László Török pg 415-419, The Kingdom of Kush by László Török pg 442-443)

The Kushite Nature of Early Meroitic Mortuary Religion by Janice W. Yellin pg 396-37, 403, Between Two Worlds by László Török pg 418-419)

The Royal and Elite Cemeteries at Meroe Janice W. Yellin pg 568-569, 577)

The Kushite Nature of Early Meroitic Mortuary Religion by Janice W. Yellin pg 400-401

The Royal and Elite Cemeteries at Meroe Janice W. Yellin pg pg 577

The Oxford Handbook of Ancient Nubia by Bruce Williams pg 566

The Double Kingdom Under Taharqo by Jeremy W. Pope pg 14-15

The Royal and Elite Cemeteries at Meroe Janice W. Yellin pg pg 570, 573-4)

The Royal and Elite Cemeteries at Meroe Janice W. Yellin pg 575-77)

The Oxford Handbook of Ancient Nubia by Bruce Williams pg 579-580)

The Kingdom of Kush by László Török pg 522-523)

The Quarries of Meroe, Sudan by Brigitte Cech

The royal pyramids of Meroe, Architecture construction and reconstruction of a sacred landscape by F. Hinkel

The Royal and Elite Cemeteries at Meroe Janice W. Yellin pg 568)

The Royal and Elite Cemeteries at Meroe Janice W. Yellin pg 569

Death and Burial in the Kingdom of Meroe by Vincent Francigny pg 597)

Death and Burial in the Kingdom of Meroe by Vincent Francigny pg 595, 596-7)

Death and Burial in the Kingdom of Meroe by Vincent Francigny pg 597)

The Oxford Handbook of Ancient Nubia by Bruce Williams pg 596)

Death and Burial in the Kingdom of Meroe by Vincent Francigny pg 601-602)

The Kingdom of Kush by László Török pg 528-529)

The Oxford Handbook of Ancient Nubia by Bruce Williams pg 601, 569)

The Kingdom of Kush by László Török pg pg 498)

Between Two Worlds by László Török pg 420-421 The Oxford Handbook of Ancient Nubia by Bruce Williams pg 597)

Between Two Worlds by László Török pg 494-495)

Between Two Worlds by László Török pg 422-424)

The Kingdom of Kush by László Török pg 515)

Death and Burial in the Kingdom of Meroe by Vincent Francigny pg 593)

The Oxford Handbook of Ancient Nubia by Bruce Williams pg 593)

The Kingdom of Kush by László Török pg pg 484)

The Archaeology of Late Antique Sudan pg 28-29)

The Nubian civilizations are woefully underappreciated in comparison to Egypt imo, so much to learn and study, plus in many ways they outlasted their Northern neighbors far longer and had a more consistent military and political autonomy.