The Surgeons and Physicians of pre-colonial Africa: a brief medical history

In 1908, a team of archaeologists surveying Lower Nubia uncovered a collection of remains from elite cemeteries that provided evidence of early medical intervention. Among the finds were the remains of a girl dated to the 7th century, whose forearms bore two sets of splints, suggesting deliberate treatment of fractures.1

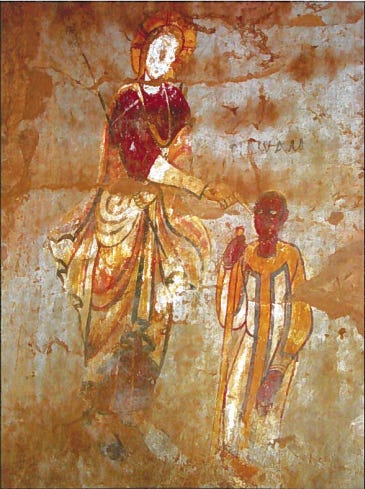

Results from more recent excavations at the monastery of Khom H at Old Dongola, Sudan, indicate that during the 12th century, sections of its North-Western annex were used as a xenon, a type of hospice or hospital more commonly found in the Byzantine world. This indicates that the Nubian monks of Khom H provided medical care alongside their other religious and communal roles. Supporting this interpretation are two distinctive wall paintings: one depicting Saints Cosmas and Damianus receiving bags of medicinal substances from an angel, and the other showing Christ healing a blind man at the Pool of Siloam.2

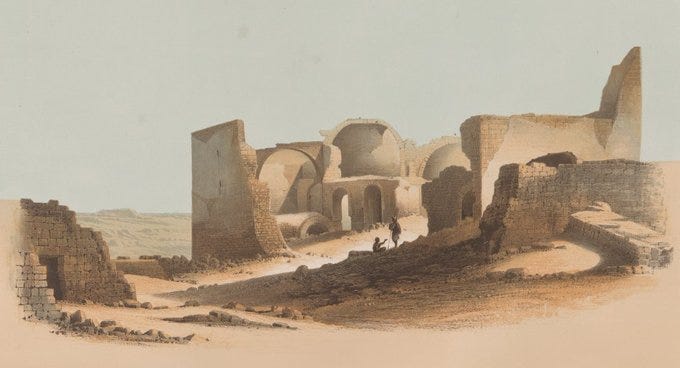

Archaeobotanical research at the monastery of Ghazali, further north, indicated the presence of several plant species in the monastic storerooms, including Euphorbia aegyptiaca, which, due to its antiseptic properties, is still used in herbal medicine to treat inflammations, rheumatism, and arthritis.3

19th-century painting of the ruined monastery of Ghazali, Sudan. (Klosterruine von Wadi Gazâl, Denkmaeler aus Aegypten und Aethiopien, 1849)

Ruins of the Monastery of Ghazali

Christ healing a blind man at the pool of Siloam. Northwest Annex, Khom H Monastery, Sudan. image by Małgorzata Martens-Czarnecka

Support AfricanHistoryExtra by becoming a member of our Patreon community, subscribe here to read more about African history, download free books, and keep this newsletter free for all:

The history of medicine in pre-colonial Africa has been the subject of extensive ethnographic studies, complemented more recently by historiographic and archaeobotanical research.

Most of the ethnographic studies are based on the observations of colonial administrators and missionaries and reflect the cultural biases of their authors. They nevertheless provide crucial insight into African medical traditions.

Arguably, the most significant of these was the practice of inoculation against smallpox, which was introduced to America by enslaved West Africans in the 18th century and was derived from a fairly common practice across the continent.4

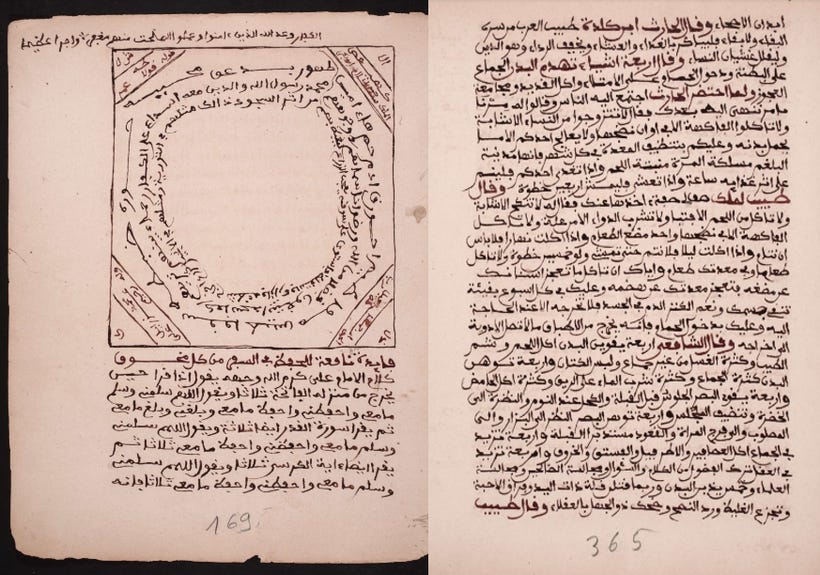

While historical research on African medical writings remains in its early stages, a substantial corpus of medical manuscripts has been recovered from private libraries across West Africa, with the earliest examples dating to the 15th century. These texts contain a wide range of medical knowledge, including records of empirical experimentation, classification of diseases, pharmacological treatises, anatomical descriptions, and a handful of works devoted to eye diseases and surgery.

Shifāʼ al-asqām al-ʻāriḍah (Book on curing external and internal illnesses) by the 17th century scholar Ahmad al-Raqqadi. Mamma Haidara Library. Timbuktu, Mali.

Of particular importance to the development of scientific medicine in Africa are historical accounts of surgical practice. Unlike most therapeutic interventions, surgery requires a sophisticated understanding of anatomy, anesthesia, and asepsis.

Beyond the widely attested treatment of wounds, the management of fractures, and the performance of medical amputations, documentary sources point to a high level of technical proficiency among physicians and surgeons in many parts of Africa. This expertise is especially evident in more complex procedures, including craniotomy (trephination) and abdominal surgery.

Trephination is an ancient surgical procedure that has been documented in many parts of the world and is often regarded as an early form of brain surgery.5 It was primarily used for treating skull fractures, mostly among war casualties, but was also used for other neurological conditions.

The operation was typically performed by general medical practitioners and could last several hours. Patients were ordinarily administered medicinal preparations in advance of the procedure. In simplified terms, the technique involved drilling a small hole into the skull to access the dura mater and relieve increased intracranial pressure.

Survival rates varied greatly, and the operation was upto the late 19th century, regarded by modern surgeons as extremely difficult.6 However, ethnographic accounts and archeological evidence suggest high survival rates for trepanations performed across many African and other non-Western societies, which often surpassed those undertaken by European and American operators in the 19th century.

A series of thirty-two trephinations carried out at St. George’s and Guy’s Hospitals (London) from 1870-77 carried a mortality of about 65%, while field hospitals during the American Civil War had survival rates ranging from 46-56%. On the other hand, survival rates were as high as 75% among the natives of Malenesia, 80% among the pre-colombian Inca, and 95% for the craniotomies performed by the Gusii/Kisii of Kenya.7

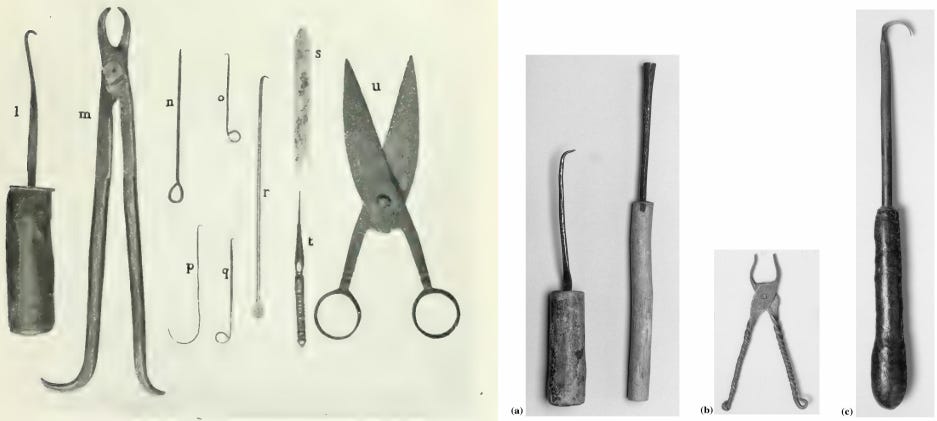

There are numerous ethnographic accounts describing trephination from the early to mid 20th century in different African societies. The most detailed are the accounts of Hilton-Simpson (1922) among the Shawiya of N.E Algeria, Margetts (1967) among the Kisii of Kenya, Dalloni (1935) among the Teda of Chad, Drennan (1937) among the Khoe-San of South Africa, Drake-Brockman (1912) among the Somali, and John Roscoe (1921) among the Basoga of S.E Uganda.8

The account of John Roscoe describing the skill of ‘native surgeons’ in the kingdom of Busoga, who were often called to operate on skull fractures caused by the sling-shot, indicates that such operations were undertaken multiple times:

“The accuracy with which they aim these missiles is proved by the dented skulls of many victims. The surgeons, therefore, get much practice in this kind of work, and they have learned how to remove splinters of bone from the brain and thus restore men, who would otherwise die or live insane, to life and reason.”9

(Left) Dental and Ophthalmic instruments, for eye surgery, used by the Shawiya Berbers of Algeria. Images by Hilton-Simpson. (right) Medical instruments collected from Ankole (Uganda) by J Roscoe, and Hausaland (Nigeria). Image by Peter A.G.M. De Smet.

(left) grooming kit; tweezers, a kohl stick, a probe, a hooked probe, and a razor. Ballana, Lower Nubia, late Meroitic period. The Institute for the Study of Ancient Cultures, The University of Chicago. (Right) Gold necklace in the form of a grooming kit. Akan peoples, Ghana. 1895–1905. Houston Museum of Fine Arts.

Early ethnographic accounts of the Maasai (along the Kenya/Tanzania border) indicate that their surgeons and physicians were exceptionally skilled in the management of fractures and the performance of abdominal surgical procedures.

The colonial administrator Harry Johnston, who visited Masailand in the late 19th century, wrote :

“The Masai possess several therapeutical and empirical remedies, they are acquainted with laxatives, tonics, sudatories, and excitants. With regard to surgery, they are able in a rough-and-ready fashion to deal with the cure of wounds, the arresting of hemorrhage, and the mending of broken bones. When a large wound has been inflicted, the two sides are brought together by means of the long, white thorns of the acacia, which are passed through the lips of the wound like needles. A strip of fibre or bass is then wound round the exposed points of the thorns on each side of the wound, just as a boot might be laced up. A fractured limb is straightened as far as possible so that the broken ends of the bone may come together, and is then tightly bandaged with long strips of hide.”10

The relatively detailed description of Maasai medical practice provided by the German ethnographer Moritz Merker, who reached Maasailand in the late 1890s, goes further than that of Johnston. Merker’s account indicates that the Maasai had a professional class of surgeons whose medical knowledge was grounded more in empirical and practical principles than in religious ritual, and who regularly carried out surgical procedures with a high rate of success.

“Unlike other ethnic groups, the Maasai never attribute the origin of internal illnesses to the actions of evil spirits, they see the causes of illness in external or internal influences harmful to the person.

Surgery is the domain of specialized surgeons (ol abáni, el abak). The profession is generally passed down from father to son. Only the son of an el abani (surgeon) who understands how to practice the art is an ol abani (surgeon), and only as long as he practices it. If, exceptionally, someone whose father is not a surgeon learns the art, he thereby becomes a surgeon. The surgeon thus practices a liberal profession. As payment for services rendered, the ol abani receives, depending on the severity of the case or the amount of work he has done, a head of livestock, ranging from a cow down to a young goat or a lamb. It is also worth mentioning the noteworthy arrangement that he can only claim payment if his treatment has been successful and that the patient is not entitled to payment before complete recovery.”11

Among several examples of the operations undertaken by Masai surgeons, Merker describes one that occurred in November 1901, in which a boy who had broken his right tibia close to the knee, was successfully operated upon by a local surgeon. The latter cut the lower leg on the tibia to just above the knee, and peeled away the lower end of the bone to the same extent. He then broke it off about ten centimeters above the lower joint, removed the rotting marrow from the remaining bone, cleaned the wound with warm water and its upper part by scraping it, and sutured it. Three months later, the boy was already able to walk around and resume his work as a herder.

Other surgeries involved arrows and spearheads that were lodged in the lungs or abdomen. The surgeon carefully extracted the arrowhead, sewed the severed abdomen and internal organs using a thread, or washed them with warm water in case they were exposed, before setting them back in place and sewing the inner and outer edges of the now enlarged entry wound, and closing it with a looped suture.12

This brief outline of pre-colonial African surgeons and physicians demonstrates the level of development of scientific medicine across the continent that has often been overlooked in broader African historiography.

Such isolated knowledge of African historical surgery and scientific medicine is best exemplified by the remarkable account of a caesarean section performed in 1879 in the town of Kahura, in what is today central Uganda.

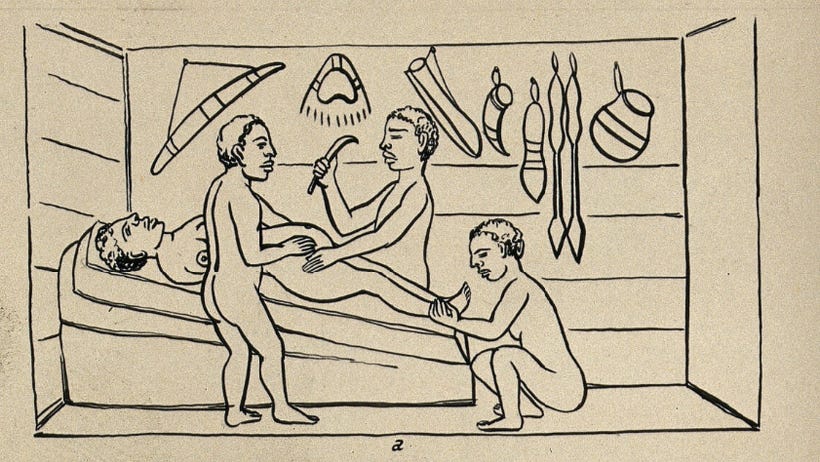

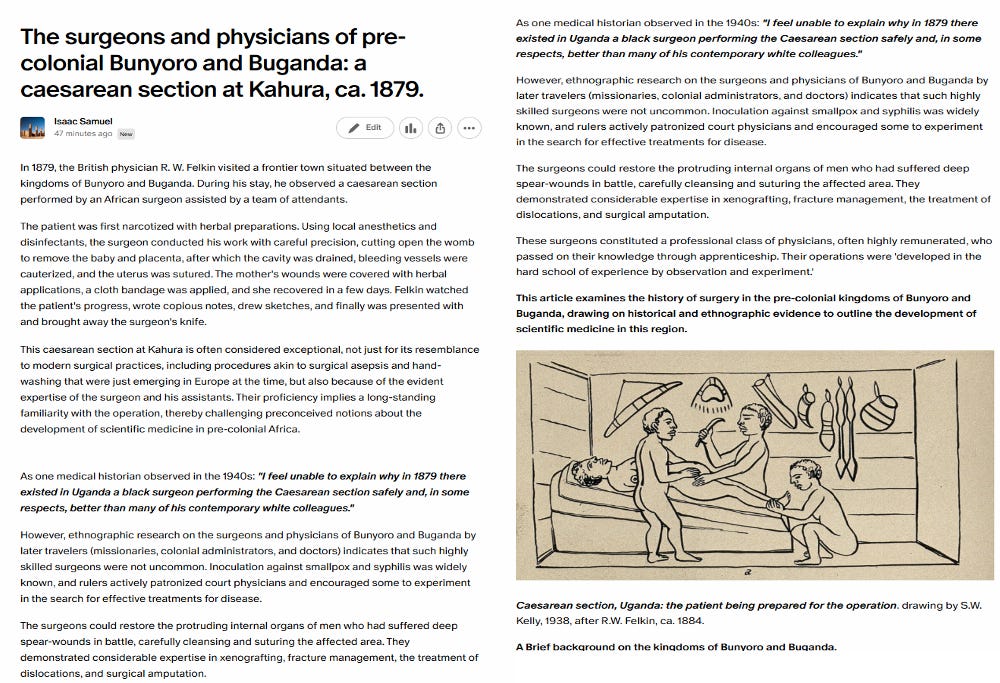

In 1879, the British physician R. W. Felkin visited a frontier town situated between the kingdoms of Bunyoro and Buganda. During his stay, he observed a caesarean section performed by an African surgeon assisted by a team of attendants.

The patient was first narcotized with herbal preparations. Using local anesthetics and disinfectants, the surgeon conducted his work with careful precision, cutting open the womb to remove the baby and placenta, after which the cavity was drained, bleeding vessels were cauterized, and the uterus was sutured. The mother’s wounds were covered with herbal applications, a cloth bandage was applied, and she recovered in a few days. Felkin watched the patient’s progress, wrote copious notes, drew sketches, and finally was presented with and brought away the surgeon’s knife.

This caesarean section at Kahura is often considered exceptional, not just for its resemblance to modern surgical practices, including procedures akin to surgical asepsis and hand-washing that were just emerging in Europe at the time, but also because of the evident expertise of the surgeon and his assistants. Their proficiency implies a long-standing familiarity with the operation, thereby challenging preconceived notions about the development of scientific medicine in pre-colonial Africa.

As one medical historian observed in the 1940s: “I feel unable to explain why in 1879 there existed in Uganda a black surgeon performing the Caesarean section safely and, in some respects, better than many of his contemporary white colleagues.”13

Caesarean section, Uganda: the patient being prepared for the operation. drawing by S.W. Kelly, 1938, after R.W. Felkin, ca. 1884.

However, ethnographic research on the surgeons and physicians of Bunyoro and Buganda by later travelers (missionaries, colonial administrators, and doctors) indicates that such highly skilled surgeons were not uncommon. Inoculation against smallpox and syphilis was widely known, and rulers actively patronized court physicians and encouraged some to experiment in the search for effective treatments for disease.

The surgeons could restore the protruding internal organs of men who had suffered deep spear-wounds in battle, carefully cleansing and suturing the affected area. They demonstrated considerable expertise in xenografting, fracture management, the treatment of dislocations, and surgical amputation.

In an effort to reconcile their own observations of highly skilled African physicians with prevailing racial prejudices, later travelers and colonial officials frequently attributed such knowledge to diffusion from ancient Egypt rather than to local intellectual traditions.

As one colonial administrator in Bunyoro wrote in the 1910s:

“The simple knowledge of surgery possessed by the Banyoro was evidently acquired through the Egyptians. Vaccination for small-pox was known long before European influence reached them. It seems humiliating to find that some of our boasted modern methods of surgery were known and practised by these half-savage tribes.”

The history of surgeons and physicians of pre-colonial Bunyoro and Buganda is the subject of my latest Patreon article. Please subscribe to read more about it here:

The Oxford Handbook of Ancient Nubia, edited by Bruce Williams et al, pg 1054, The Most Ancient Splints by GE Smith. The archaeological survey of Nubia: report for 1907-1908 by George A. Reisner et al pg 13-14

The Medieval Kingdoms of Nubia: Pagans, Christians and Muslims along the Middle Nile by Derek A. Welsby, pg. 104

The monasteries and monks of Nubia by Artur Obłuski pg 209

Smallpox Inoculation in Africa by Eugenia W. Herbert

Most brain surgery isn’t about fixing the brain itself, but is, in fact, skull surgery done to protect the brain tissue from compression by creating space for it to survive swelling from trauma or bleeding

On Trephination, see A Hole in the Head by Charles Gross

Primitive Surgery by Erwin H. Ackerknecht, pg 32-33

The Early History of Surgery By William John Bishop pg 24. Trepanation Procedures/Outcomes: Comparison of Prehistoric Peru with Other Ancient, Medieval, and American Civil War Cranial Surgery by David S. Kushner et al.

African Folk Medicine Practices and Beliefs of the Bambara and Other Peoples By Pascal James Imperato pg 182-184

‘Hat on – hat off’: trauma and trepanation in Kisii, western Kenya by Sloan Mahone pg 333

The Uganda Protectorate by Harry Johnston pg 831

Die Masai : ethnographische Monographie eines ostafrikanischen Semitenvolkes by Moritz Merker pg 193-5

Die Masai : ethnographische Monographie eines ostafrikanischen Semitenvolkes by Moritz Merker pg 179-197

Primitive Surgery by Erwin H. Ackerknecht, pg 32

This was phenomenal, and as a physician-scientist, I’m grateful for how rigorously you dismantle the “medicine arrived with Europe” myth using concrete, checkable examples (archaeologic evidence of intervention, documented fracture care, and the famous Bunyoro/Buganda C-section account). What lands hardest is the implication for how we teach “medical progress.” Your post shows that surgical technique, procedural sterility logic, and preventive practices (e.g., inoculation/vaccination practices) weren’t a one-directional diffusion from “civilized” to “uncivilized”; they emerged in multiple places, adapted to local constraints, and were then selectively recognized (or dismissed) through a colonial lens.

There’s also a modern clinical echo here: when we erase Indigenous and African medical histories, we don’t just distort the past, but we weaken today’s trust architecture in global health by implying expertise is imported rather than locally rooted. Posts like this do something quietly important: they restore epistemic dignity while staying grounded in evidence.

This is incredible. Never knew the African countries in medieval times did such awesome medical practices. Knowledge is indeed powerful.