The Swazi kingdom and its neighbours in the 19th century: from the rise of Zulu to the British

an island in the maelstrom

The political landscape of southern Africa in the 19th century was a hotbed of revolutionary states and colonial expansion. Wedged between powerful African kingdoms and an expanding colonial frontier was the Swazi Kingdom which occupied a pivotal position in the region.

Since its establishment in the 18th century, the Swazi kingdom played a critical role in southern Africa's political history. From the meteoritic rise of the Zulu kingdom, to the foundation of the Trekker republics and British colonization, Swazi navigated the era’s extremely fluid political relationships with its neighbors inorder to maintain its autonomy.

This article outlines the history of the Swazi kingdom and its neighbors in the 19th century, and the outsized role that the kingdom played in southern Africa's political history.

Map showing the kingdoms of Southern Africa in the early 19th century

Support AfricanHistoryExtra by becoming a member of our Patreon community, subscribe here to read more about African history, download free books, and keep this newsletter free for all:

Early history of the Swazi kingdom between the Zulu and Ndwandwe kingdoms; 1750-1850

The emergence of large kingdoms in southern African such as the Swazi, Zulu, Pedi, and Ndwandwe, was the culmination of centuries of social and political developments occurring in the pre-existing small-scale states across the region. The history of the Swazi state as recounted by its king-list is among the oldest in the region. Genealogies about the kingdom's ruling dynasty; the Dlamini, posits the dynasty's establishment around the late 1st millennium, but besides a few toponyms about royal burial sites and some corroboration in neighboring king-lists, most of the information in the Swazi king-list is not very reliable until the mid-18th century.1 Its during the 18th century that the nucleus of the Swazi state --known as Ngwane-- was founded in what is now southern Swaziland (etshiselweni) by Nguni speakers, and its the state of Ngwane that would after its expansion northwards produce the Swazi kingdom.2

Prior to the Swazi's ascendance in the early 19th century, the region was briefly dominated by the Ndwandwe kingdom which successfully defeated and subsumed many smaller states during the 1790s and 1810s, in a similar way as Shaka of the Zulu kingdom was expanding his own state to its south, thus setting up a major conflict between the two kingdoms which was ultimately decided in the monumental defeat of Ndwandwe by the Zulu army after the 1819 war3. The Swazi state had during this period, been firmly established under the Kings Ngwane (d. 1780) and Zikode (d. 1815), and was greatly expanded under king Sobhuza (r. 1815-1850) who subsumed many pre-existing polities through diplomacy and conquest, briefly putting his kingdom on collision path with the Ndwandwe kingdom in an destructive series of battles that only ceased after Ndwandwe's fall to the Zulu.4

King Sobhuza's state after Ndwandwe's collapse re-established a precarious form of order, it was constrained by reduced military capacity and the social upheaval of Ndwandwe-Zulu wars but advantaged by strategic political alliances that the king had established through marriage as well as ritual power which brought more polities into the Swazi kingdom. Sobhuza accomplished an exceptional feat of diplomacy with the Zulu king Shaka by employing the same marriage and religious alliances as a nominal tributary state to placate Zulu's dreaded army, but ultimately rebelled and fought off two Zulu invasions in 1827.5

Swazi’s troubles with Zulu continued under Shaka's successor Dingane, who had assassinated the former in conspiracy with his brother Mpande, and then imposed a trade blockade on Swazi in 1834 because the latter state had become prosperous during Zulu’s interregnum. Dingane afterwards sent his forces against Swazi in 1836 and 1839. The two invasions were politically indecisive, the first captured some cattle as Sobhuza had tacitly withdrawn, but the second invasion was decisively defeated ending in a negotiated settlement with the Zulu through the auspices of the Portuguese from Delagoa Bay. Despite Dingane's successful diplomatic overtures to the Portuguese to secure a truce with Swazi, his poor military record eventually undermined his authority relative to his brother Mpande. The upstart Mpande allied with the newly arrived Trekkers (sections of Dutch-speaking Boer settlers fleeing from the British-controlled cape-coast colony) in 1840, and defeated Dingane at the Battle of Maqongqo (although largely using his own forces).6

chiefdoms that made up the Swazi kingdom, 18207

The Swazi kingdom between the Boer republics and the Zulu kingdom: 1850-1877

The arrival of the trekkers on the borders of the Swazi kingdom would have profound effects on the regions' political history especially after they established a short-lived republic called Natalia in 1839 whose capital was at Natal just south-west of Zulu. But Swazi’s prior interactions with European traders and missionaries provided the state with a slight advantage over its peers. King Sobhuza had already established trade contacts with the Portuguese at Delagoa Bay in response to the burgeoning ivory and cattle trade, and had recognized the value of firearms which he deployed in his own forces using the service of Portuguese mercenaries to put down rebellions. In 1834, he contacted the Wesleyan missionaries in the cape colony, with a request for the latter to proselytize in a disputed region between the Swazi and the Zulu, inorder to create a buffer zone against the latter. Just prior to the Zulu civil war between Mpande and Dingane, Swazi envoys were also sent to the trekkers to form an alliance against the Zulu king Dingane, and the Swazi-Natal relationship continued after Dingane’s defeat in 1840, when the Swazi brought the remains of Dingane to confirm their support.8

Coinciding with the trekkers' arrival in the region were the expanding British colonial interests. The war that brought the Zulu king Mpande into power elevated Natalia's position in the region's politics relative to the British’s cape colony, and this prompted the British to invade and annex the Natalia republic in 1842-3.9 Wars were often followed by the migration of the defeated parties and their possessions, but attempts at forcefully recovering these risked escalation to war. In the period following Sobhuza’s death, the Swazi kingdom was embroiled in succession crisis as rival candidates to the throne sought Zulu and Trekker assistance to install them and depose the young king Mswati. Since the trekkers had moved north of Swazi in 1845, the newly installed Swazi king Mswati (r. 1850-1865) juggled alliances between them and the British in Natal, against the Zulu kingdom, while the Zulu king leveraged his own regional alliances among neighboring trekkers and African states, and tried to create a pretext through Swazi's succession disputes to repatriate defeated Zulu factions in Swazi, while also placating the British at Natal who intended to invade the Zulu. In 1852, the Zulu armies invaded Swaziland but later withdrew after the action had strengthened Swazi's ties with the British in Natal.10

Having fended off the Zulu threat, the Swazi state then continued its gradual expansion, it turned Portuguese dependencies in the Delagoa bay into its own vassals after a series of wars during 1855-8 and 1862-3, brought many small states in the region into its orbit as tributaries.11 Swazi was also engaged in extensive commodities trade with the Transvaal republic --one of the states formed by the trekkers to its northwest. While the initial trekker movement in the 1830s represented a formidable force, their dispersion into disparate communities by the 1840s soon reduced them to minor players in the largely African-dominated political economy of the region. The different trekker communities’ isolation and their resulting military weakness, forced them into relations of symbiotic dependence with neighboring African kingdoms for trade and security. Transvaal required Swazi assistance against Venda kingdom in 1867 and Pedi kingdom in 1876.12 So while Transvaal republic was granted land in 1855 by Swazi to serve as a buffer against Zulu, their dependence on Swazi for military and commercial needs meant that effective occupation remained with the Swazi, since treaties were effectively inconsequential if not backed by military capacity to enforce them.13

Succession crises in Swazi after the death of Mswati in 1865 created a power vacuum during the regency of the boy-king Ludvonga (1865-1874) in which Transvaal attempted to turn the tables on Swazi. Around 1867, a more permanent settlement called 'new Scotland' was established by McCorkindale south of Swazi state in the buffer zone claimed by Transvaal but effectively controlled by the Swazi. McCorkindale's interests were to establish direct trade to Delagoa bay through Swaziland and his assertive demands forced the Swazi court to send an embassy to the British in Natal objecting to McCorkidanle's plans. While McCorkidanle died in 1871, he had stirred expansionist sentiments in Transvaal, which moved to make its settlement south of Swazi formal in 1869, but abortive military campaigns failed to make this practical. Other plans were made by Transvaal officials to build a rail-line through Swaziland to Delagoa Bay in 1871-1872 but these too were abandoned due to lack of capacity, their only effect being to force the Swazi to place even more pressure on the British to mediate on their behalf.14

Internal conflicts in Swazi had culminated in the assassination of the boy-king Ludvonga in 1874 and the installation of Mbandzeni (r.1874-1889) despite the protests of the Swazi councilors. During this Swazi interregnum, the discovery of diamonds in Kimberly in 1866 had strengthened British resolve to advance further inland and colonize the entire region, this threatened to engulf Swazi and their African and Boer neighbors who thus sought to break the gridlock by creating larger states to counter the British threat. In 1875, the Zulu king Cetshwayo attempted to invade Swaziland but Swazi’s military ally, Transvaal, used this as a pretext to force less favorable terms on Swazi kingdom with intention of annexing it, forcing Swazi to shrewdly play competing British interests in a pact against Transvaal. In 1876, Transvaal used Swazi forces to invade the Pedi kingdom of king Sekhukhune, but left most the fighting to them, disappointed by the trekker’s “cowardice” in battle, the Swazi forces withdrew. Transvaal’s army was defeated by the Pedi, and soon after Transvaal was defeated by the British as well who annexed its territory in 1877.15

Map of colonial warfare in late 19th century southern Africa.

The Swazi kingdom and the British (1877-1902)

True to the fluid nature of its alliances, Swazi's newfound relationship with the British remained deliberately ambiguous as the Swazi courtiers had as much reason to fear being engulfed by the British just as much as their more proximate enemy; the Zulu kingdom. Swazi declined to assist the British in their war against the Pedi kingdom in 1878, and sent its councilors Sandlane Zwane and Mbovane Fakudze to attend the Queen's birthday celebrations in Natal (an event intended for the newly colonized chiefs to pledge fealty to the British), but they refused to be lumped together with others as subjects, instead stressing their independence. While the response the councilors received from the British governor Theophilus Shepstone all but threatened to colonize the Swazi kingdom, more urgent internal matters in Natal, and the break out of the Anglo-Zulu war in 1879 gave the Swazi some temporary reprieve.16

At the onset of the Anglo-Zulu wars, Swaziland was on the frontline of the conflict and the Swazi king Mbandzeni was aware of his state's vulnerability. The Zulu kingdom was the unchallenged military power of the region, and the Swazi were obliged (by their earlier pact with the British against Transvaal) to provide troops to assist the British in the war against the Zulu. This obligation however, was never met, and like in the 1878 British wars against Pedi, the Swazi kingdom’s official communications to the British commanders MacLeod and Wolseley and various colonial officials, employed a mix of deception and delay throughout the entire course of the campaigns and avoided sending their armies into Zulu. "The Swazi performance during the war had been a truly masterly display of fence-sitting. Without actually doing anything they had managed to project an image of loyalty, which won them tributes from all sides once the fighting ceased".17 Free from the Zulu threat, Swazi forces now joined the British in the war with the Pedi in 1879, and despite the Transvaal's victory in their rebellion against the British in 1881, Swazi managed to secure the recognition of its independence from both states.18

The persistent convergence of imperial interests in southern Africa continued to threaten Swazi autonomy, at a time when internal Swazi contests of power between the king Mbandzeni and the councilors were at their height. The discovery of gold in north-western Swaziland in 1875, and the granting of temporary grazing and mining concessions to different settlers as a contest of authority between the King and the councilors, increasingly created a new threat to Swazi's political cohesion. These concessions were essentially rent-paying land leases for short periods of time and were deemed less costly to the Swazi court than exploiting the minerals itself. All concessions were initially fully under Swazi law (given its capacity to enforce or nullify them) and many were not utilized (since mining grants were speculative and many settlers lacked capital), but their existence would eventually prove to be very damaging19.

The Swazi kingdom's council had decided to choose a single concessioner named Arthur Shepstone to regulate the activities of the others, but the decision was vetoed by the king who feared the potential threat to power posed by one concessioner. King Mbandezi instead preferred to grant many different settlers whose divided interests he could control —the Boers got grazing rights while the British got mining rights thus keeping them at loggerheads with each other. Its for this same reason that the king had also refused the British's demand for Swazi to house a British resident in the Swazi capital who would have collected taxes and effectively turned Swazi into a British colony.20

But unlike earlier occasions when Swazi could play off various competing interests, the re-established Transvaal republic after 1881 was a much stronger state with little need for Swazi military assistance, and the British protection pact with the Swazi was now subject to the impossible demand that a British resident be set up in the Swazi capital. So when Transvaal's vice-president Landdrost Krogh requested a large concession from the Swazi king in 1885 (acting in both official and private capacity with threats of annexation) it was granted to him.21

Aware of the threat that Transvaal-backed concessionaries would create in Swaziland, king Mbandzeni decided to invite Arthur Shepstone in 1886 inorder to regulate the activities of the concessionaries from falling under Transvaal's control. While initially successful, opposition from some concessionaries allied to the different Swazi councilors opposed to Mbandzeni, and Shepstone's diplomatic inability to secure Swazi's eastern possessions from Portuguese claims, undermined any attempts at curtailing concessionary activity. Swazi had exhausted its diplomatic arsenal.22

Rather than mediating the emerging colonial and commercial pressures, Swaziland found itself the object of their attentions. Mbandzeni spent the last years of his reign terminally ill and barely able to function as a king, internal conflicts between the councilors led to a spell of a executions. concessioners increasingly became unruly and the Swazi court was forced to establish a committee to oversee their activities in 1888 although many objected to joining it. King Mbandzeni died in 1899, and Transvaal gained more control over the swazi kingdom in 1890 and would formally divide it in 1893 between Swazi and British control, and this political situation continued through the 1899-1903 Anglo-Boer wars and ended with the British's formal occupation of Swaziland in 1902.23

Map of the Swazi kingdom showing the mineral concessions that had been granted by 1889

Conclusion: Swaziland in African history.

The Swazi kingdom's history provides a prism through which southern African history can be observed. From its establishment in the midst of the region’s political revolutions, to its skillful manipulation of European rivalries, the Swazi kingdom was able to survive the cataclysmic collapse that befell its neighbors, using its expertise in the intricacies of southern Africa’s diplomacy.

But the fundamental changes sweeping southern Africa that were precipitated by the discovery of minerals, profoundly altered the symbiotic nature of Swazi's relationship with its neighbors that had enabled it to survive for so long, and these changes eventually brought an end to its precarious autonomy.

Swazi warriors at the incwala festival, 1935

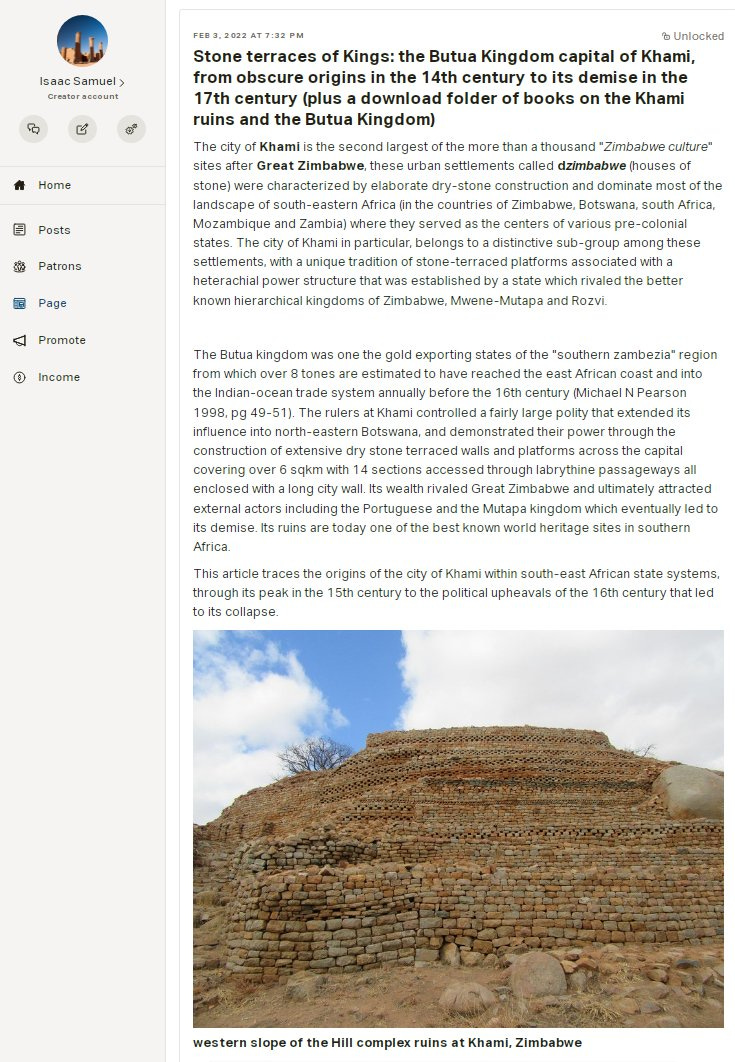

Southern Africa was home to many dynamic states including the Butua kingdom and its monumental capital at Khami, read about it here on Patreon

Kingdoms and Chiefdoms of Southeastern Africa by EA Eldredge pg 1. 92-95

The Kingdom of Swaziland by D. Hugh Gillis 9-10

Kingdoms and Chiefdoms of Southeastern Africa by EA Eldredge pg 207-212)

Kingdoms and Chiefdoms of Southeastern Africa by EA Eldredge pg 231-232, Kings, Commoners and Concessionaires by P. L. Bonner pg 27-29)

Kings, Commoners and Concessionaires by P. L. Bonner pg 34-37)

Kings, Commoners and Concessionaires by P. L. Bonner pg 42-44)

P. L. Bonner

Kings, Commoners and Concessionaires by P. L. Bonner pg 45)

An exposition of the clash of Anglo-Voortrekker interests at Port Natal leading to the military conflict of 23-24 May 1842 by A.E. Cubbin

Kings, Commoners and Concessionaires by P. L. Bonner pg 49-63)

Kings, Commoners and Concessionaires by P. L. Bonner pg 95-101)

Kings, Commoners and Concessionaires by P. L. Bonner pg 66-72, 80-84)

The Kingdom of Swaziland by D. Hugh Gillis pg 30-31

Kings, Commoners and Concessionaires by P. L. Bonner pg 117-122)

Kings, Commoners and Concessionaires by P. L. Bonner 128-145, The Kingdom of Swaziland by D. Hugh Gillis pg 32-33

Kings, Commoners and Concessionaires by P. L. Bonner pg 148-150)

Kings, Commoners and Concessionaires by P. L. Bonner pg 150-158)

The Kingdom of Swaziland by D. Hugh Gillis pg 34-36

The Kingdom of Swaziland by D. Hugh Gillis pg 48-53

Kings, Commoners and Concessionaires by P. L. Bonner pg 171-174)

Kings, Commoners and Concessionaires by P. L. Bonner pg 174-178)

The Kingdom of Swaziland by D. Hugh Gillis pg 38-40, Kings, Commoners and Concessionaires by P. L. Bonner pg 183-196

The Kingdom of Swaziland by D. Hugh Gillis pg 60-80

Brilliant, really interesting and filled in many gaps.

A lot of details.