Trans-continental trade in Central Africa: The Lunda empire's role in linking the Indian and Atlantic Worlds. (1695-1870)

Central Africa's international trade as seen through the travelogues of African writers.

Among the recurring themes in Central African historiography is the region's presumed isolation from the rest of the world; an epistemological paradigm created in explorer travelogues and colonial literature, which framed central Africa as a "unknown" inorder to christen explorers and colonists as "discoverers" and pioneers in opening up the region to international Trade. While many of the themes used in such accounts have since been revised and discarded, the exact role of central African states like the Lunda empire in the region’s internal trade is still debated.

Combining the broader research on central Africa's disparate trading networks terminating on the Indian and Atlantic coasts reveals that the Lunda were the pioneers of a vast Trans-continental trade network that reached its apogee in the 18th and 19th century, and that Lunda’s monarchs initiated alliances with distant states on both sides of the continent, which attracted the attention of two sets of African travelers in 1806 and 1844 coming from both sides of the continent, who wrote detailed accounts of their journey across the Lunda's domains from an African perspective —nearly half a century before David Livingstone's better known cross-continental trip across the same routes in 1852.

This article describes the role of the Lunda empire in Trans-continental, international trade in central Africa, and its role in uniting the eastern and western halves of central Africa, through the travelogues of two African writers who visited it.

Map of central Africa showing the routes used by the Ovimbundu trader Baptista in 1806 (Yellow), the Zanzibari trader Said in 1844 (Green) and the Scottish traveler David Livingstone in 1852 (Red)

Support AfricanHistoryExtra by becoming a member of our Patreon community, subscribe here to read more about African history, download free books, and keep this newsletter free for all:

The Lunda state and the African trading groups

The 18th century in Central Africa opened with the emergence of the Lunda Empire and its rapid expansion to both the east and west, ultimately reaching the banks of the Kwango River (in eastern Angola) and the shores of Lake Mweru (in northern Zambia). The Lunda state had been established in the mid 17th century but was ruled by elected titleholders and only full centralized in 1695 with the ascension of King Nawej who then introduced a number of political and commercial innovations that enabled the Lunda to subsume neighboring polities and graft itself into the region’s trade networks. 1

Through the various merchant groups such as; the Yao in the east; the Nyamwezi and Swahili in the north-east; and the Ovimbudu in the west, the Lunda’s trade goods were sold as far as the Mozambique island, the Swahili Coast and the coastal colony of Angola, making it the first truly trans-continental trading state in central Africa.

Map of the Lunda-Kazembe empire with some of the neighboring states that are included in this article

While the inability to use draught animals —due to the tse-tse fly's prevalence— constrained the mobility of long distance trade in heavy goods, the Lunda overcame this by trading only those commodities of low weight and high value that could be carried along the entire length of the caravan trade routes, these were primarily; cloth , copper, and ivory.2 And while their trade wasn’t central to the Lunda’s primarily agro-pastoralist economy nor was controlling the production of export commodities the the sole concern of Lunda’s state-builders, these goods comprised a bulk of its external trade.

The caravan routes that Lunda grafted itself onto were pioneered by various trading groups comprised primarily of a professional class of porters especially the Nyamwezi and the Yao who essentially invented the caravan trade of central Africa.3

Many colonial writers and some modern historians assume that long distance caravan porters were captive laborers. This mischaracterization was a deliberate product of the imperial discourses at the time which were later used to justify the region's conquest and occupation and greatly distorted the realities of the dynamics of trade in central Africa.4 Professional caravan porters were wage laborers and innovators at the forefront of central Africa's engagement with the global economy, they were key players in the development of new social, economic and cultural networks and created the framework of the region's integration and economic development.5

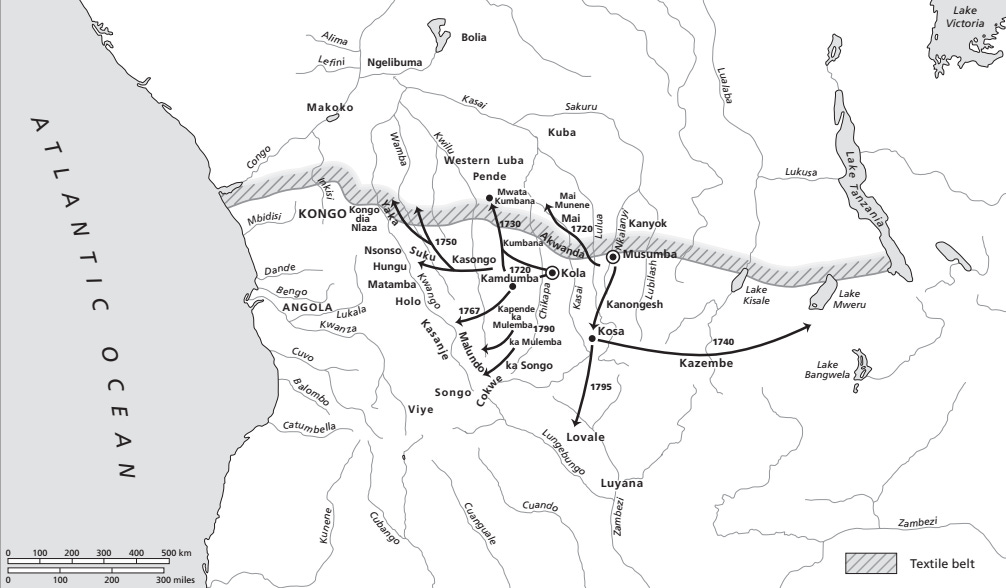

Expansion of the Lunda empire along the “Textile belt” in the early 18th century

The Lunda's earliest major expansion and most significant in the empire's traditions was into the Textile producing regions, and by 1680, the Lunda textile exports were reaching the Imbangala kingdom of Kasanje from which some were sold in the coastal colony of Angola. This trade later came to include copper which by 1808 was being exported to Brazil through Luanda.6 This expansion north was however challenged and Nawej was killed, the Lunda thus expanded west pushing into the Textile belt and increasing its textile trade with Kasanje thus attracting the interest of the Angola-based Portuguese who then sent a mission to Kasanje in 1755 led by Correia Leitão. 7

Cross-continental trade across the Lunda domains was likely already established by then, as Correia Leitão was informed by African merchants in Kasanje that In the east of the Lunda domains were Portuguese trading stations where goods similar to those in Angola as well as “velvet cloth and painted paper,” could be bought. During the formative stages of the Lunda’s emergence, similar accounts had been related to the travelers; Rafael de Castro in his visit to the Lower Kasai region (north of Lunda) in 1600, and to Cadornega in the 1670s.8 But since the well-known trading groups couldn't be identified on either side of the Portuguese stations, its more likely that such trade was segmented rather than direct.

In 1740, the Lunda armies thrust eastwards and south of Lake Meru, partly with the intent of controlling the copper and salt mines of the region. The Lunda king Yavu a Nawej sent his nobles who were given the title “Kazembe’ and ordered to expand the Lunda territory. The Kazembe established their capital south of Lake Meru and instituted direct administration, collecting annual taxes and tribute often levied in the form of copper and salt, and by 1793 the Kazembe were initiating trade contacts with the Portuguese in Tete and Mozambique.9

By the early 1810s, Lunda expansion was at its height under Yavu (d. 1820) and Nawej II (r. 1821-1853) and Muteba (c. 1857-1873). who were eager to establish cross-continental trade. Lunda officials, travelled the breadth of the empire checking caravans, escorting foreign travelers and collecting tribute. 10 This state of affairs was confirmed by the two Ovimbundu traders (described below) who stayed in Kazembe’s capital between 1806-1810 and wrote that the country was peaceful and secure, and the routes were well provisioned.11

19th century Copper trade routes in Kazembe’s domains

The Lunda King Nawej, faced the challenge of maintaining central control over what was then central Africa's largest state, and the powerful eastern province of Kazembe increasingly sought complete autonomy. While Kazembe’s rulers continued to pay large tribute to Lunda as late as 1846, they styled themselves as independent Kings who conducted their own foreign affairs especially in matters of trade, they encouraged long distance Yao and Nyamwezi merchants to extend their trade networks to Kazembe and sent envoys to the Portuguese but also execrised their power by restricting the latter’s movements and blocking their planned travel to Lunda.12

It was the restriction of trade by Kazembe and the redirection of its trade by the Yao from Portuguese domains to the Swahili cities that greatly shaped the nature of Long distance trade and ultimately led to the embankment of two early cross-continental travels in the early 19th century.

Reorientation of Yao trade routes from the Portuguese to the Swahili coast.

Among the earliest long distance traders of the trans-continental trade were the Yao. Beginning in the late 16th/early 17th century, they had forged trade routes that connected Kazembe to Kilwa and Mozambique, coming from as far as the Kazembe domains, with its Portuguese trading stations at Tete, undertaking a journey of four months laden with ivory which was sold at Mozambique island between May and October.13

The Kazembe had begun trading in ivory and copper through the Yao as early as 1762, as one account from sena states “The greater part of the ivory which goes to Sena comes from this hinterland and because gold does not come from it, the Portuguese traders (of Sena) never exert themselves for these two commodities (Ivory and copper)”.14 And while the Sena traders were occupied with gold, the Mozambique island and Kilwa were keenly interested in Ivory.

By 1760, Mozambique island —an old Swahili city that was occupied by the Portuguese— is described as the primary market for ivory from the interior, with upto 90% and 50% of it in all Portuguese trading stations coming from the Yao; who had also begun to trade in gold from the Zimbabwe gold fields, with the two items of gold and ivory paying for virtually all of Mozambique's imports from India and Portugal.15

old warehouses on the Mozambique island seafront

Accompanying the Yao were the Bisa traders who carried large copper bars obtained at the court of Kazembe who had also begun to export large amounts of Ivory obtained from the Luangwa valley. By the late 18th century, small parties of these Yao and Bisa traders are said to have travelled beyond Kazembe and Lunda to eastern Angola.16

By 1765 however, the Yao's ivory trade was being redirected to Kilwa and Zanzibar, and the quantities of ivory received at Mozambique island had rapidly fallen from 325,000 lbs, to a low of 65,000 lbs in 1784. In 1795, the Portuguese governor of Mozambique island was complaining that the Yao's ivory trade to Portuguese controlled stations had fallen to as little as 26,000 lbs, writing that the Yao "go to Zanzibar for they find there greater profit and better cloths than ours".17

The high taxes imposed by the Portuguese on ivory trade, the conflict between the Portuguese authorities and the Indian merchants in Mozambique island, and the poor quality cloth they used in trade, had enabled the Swahili of Kilwa (and later Zanzibar) to outbid the Portuguese for the Yao trade.18

Several written and oral traditions in the region also confirm this reorientation of trade. In Kilwa's "ancient history of kilwa kivinje" there's mention of two Yao traders named Mkwinda and Mroka who moved from the lake Malawi to kilwa kivinje in the late 18th century and established a lucrative trade network of ivory and cloth, Other accounts from northern Malawi mention the coming of Yao and Swahili traders likely from Kilwa during this period, controlling an ivory trading network that doubtless extended to Kazembe19

Kilwa’s Makutani Palace, originally built in the 15th century but extended and fortified during the city-state’s resurgence under local (Swahili) rule the 18th century.20

Kazembe and the Portuguese of Mozambique island: a failed Portuguese mission to traverse the coast.

In 1793, the Kazembe III Lukwesa, through the auspices of the Yao and the Bisa traders, sought to establish formal contacts with the Portuguese of Tete and Mozambique island inorder to expand trade in copper and ivory. In response, the Portuguese traders then sent an envoy named Manoel to the Kazembe court, and while no formal partnership was obtained, he confirmed that the Swahili cities were quickly outcompeting the Portuguese trade.21

Lukwesa sent another embassy to the then recently appointed Portuguese governor of Mozambique island; Francisco José de Lacerda, in February 1798. Lacerda had sought to restore Portugal's dwindling commercial hegemony in central Africa following their failed political hegemony after a string of loses including; the Zambezi goldfields to a resurgent Mutapa kingdom and the Rozvi state; the loss of the Swahili cities; and their tenuous control over the coastal colony of Angola. Lacerda also hoped to establish overland communication between Angola and Mozambique island.22

Lacerda set off in July 1798 for the Kazembe's court, arriving there a few weeks later and noting that ivory trade had shifted to the Swahili coast, and that despite the rise in slave trade at Mozambique island, the Kazembe "do not sell their captives to the portuguese" as they regarded ivory a much more lucrative. (an observation backed by the relative prices of ivory versus slaves who were in low demand, the former of which fetched more than 7-15 times the price of the latter 23)

Lacerda was however prevented by the Kazembe Lukwesa from travelling west to the Lunda capital and ultimately died of a fever in Kazembe. Lacerda's entourage left a bad impression on the Kazembe, who reduced the kingdom’s trade to the Portuguese almost entirely in 1810, and wouldn't send embassies to the Portuguese at Tete until 1822.24

In 1830, the Portuguese made another attempt to formalize trade with a reluctant Kazembe and sent Antonio Gamito in 1830 to the Kazembe capital. This embassy proved futile and wasn't well received, prompting Gamito to quash any future ambitions by the Portuguese with regards to Kazembe’s trade; noting that Kazembe had no need of the Tete markets since they could obtain cloth from the Swahili coast, and that the Bisa middlemen "do not like trading in slaves".25

The commercial prosperity of Zanzibar in the 19th century confirms Gamito’s observations. The Portuguese at Mozambique island abandoned any ambitions of trading with Kazembe and any plans of cross-continental commerce were left to the African trading groups in the interior especially the Ovimbundu who undertook a near-complete trans-continental travel through Lunda to Kazembe.

Grand audience of the Kazembe (from Gamito and Antonio Pedroso’s “O Muata Cazembe”)

The Ovimbundu merchants and the Lunda: Journey of Baptista across central Africa in 1806.

The 18th century Lunda expansion west and the prospects of greater involvement in a larger trans-continental commercial network drew the Ovimbundu merchants and their kingdoms into closer ties to their east, and they had eclipsed the Imbangala kingdom of Kasanje, and by the late-19th century they had successfully re-oriented the region’s trade south through the coastal city of Benguela, and expanded Lunda's main exports west to include Ivory.26

The Kasanje monopoly over the Lunda trade was such that the Portuguese sought alternative routes, but given their previous failed missions to Lunda, this task was left to the more experienced Ovimbundu traders. In 1806, two pombeiros (also called ‘os feirantes pretos’ ie; black traders) of Ovimbudu ancestry were dispatched, their leader was called João Baptista and he made a fairly detailed chronological journal of their adventures.27

From Kasanje they headed east and were briefly detained at the Lunda capital in the court of King Yavu, after which they were allowed to proceed and they reached Kazembe's capital, where they were detained for four years because of the Kazembe's suspicions and a conflict between the Kazembe and the Bisa traders. The two traders were afterwards allowed to continue and they reached Tete in 1811 and later returned through the same route to Luanda in 1814 with more than 130 tonnes of merchandise.28 After having covered more than 3,000 kilometers not including the return trip.

Besides noting that the Kazembe's sole trade with Tete was in ivory and that no slaves reached the town (and thus Mozambique island), The two men also mentioned that they encountered companies of “Tungalagazas” (ie; Galagansa; a branch of Nyamwezi) at Kazembe's court in 1806-1810.29 thus attesting to the influence of the Nyamwezi in Kazembe’s trade by the early 19th century.

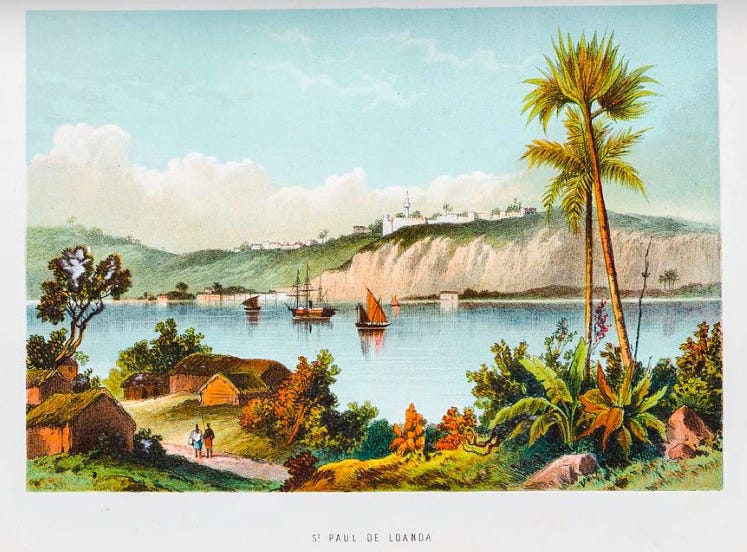

Luanda in the 19th century (from 'The Life and Explorations of Dr Livingstone’)

The Nyamwezi and Swahili: Completion of Trans-continental travel in 1852

As early as 1806, the Kazembe copper trade extended to the lands of the Nyamwezi traders who valued the "red" copper of the Kazembe more than the "white" copper imported from India through the Swahili cities.30 In 1809, the Yao traders told the traveler Henry salt while he was in Mozambique island, that they were acquainted with other african traders called "Eveezi" (Nyamwezi) who had travelled far enough inland to see “large waters, white people and horses". The strong links between Lunda-Kazembe and the coastal colony of Angola (with its white population and horses) make it very likely that Nyamwezi traders had made it to the Atlantic coast.31

While the Yao-dominated Kilwa trade with the interior was gradually declining by the mid 19th century, the Nyamwezi-dominated ivory trade which terminated at Zanzibar was beginning to flourish especially through the semi-autonomous Swahili city of Bagamoyo. Zanzibar was by then under Omani (Arab) control but their hold over the other coastal Swahili cities especially Bagamoyo was rather tenuous due to local resistance but also a more liberal policy of trade that resulted in the city becoming the main ivory entrepot along the Swahili coast from where caravans embarked into the interior. 32

The rapid expansion of the Ivory trade at Zanzibar greatly increased the demand for ivory and in the availability of credit at the coast encouraged the formation of larger caravans often led by Swahili and Arab traders who had access to it rather than the Nyamwezi, leading to the former predominating the trade into the interior while the Nyamwezi etched out their niche as professional class of porters.33

Wage rates for Nyamwezi porters per journey, 1850-190034

The swahili city of Bagamoyo, Street scene in 1889 (Vendsyssel Historiske Museum)

In response to the increased demand for ivory, the Lunda king Nawej II incorporated various Chokwe groups from the southern fringes of his empire, into Lunda’s commercial system at the capital in 1841. The Chokwe were reputed mercenaries and hunters whose lands had been conquered by the Lunda after a series of protracted wars in the 18th century.35

It’s during that 1840s that one of the earliest accounts of a Swahili trader travelling through the territories of Kazembe and across to the Atlantic coast emerges36. The German traveler Johann Ludwig Krapf, while staying in Kilwa kivinje in March 1850, was told of a “of a Suahili (swahili), who had journeyed from Kiloa (Kilwa) to the lake Niassa (Malwai) , and thence to Loango on the western coast of Africa.”37

In 1844/5, a large ivory caravan consisting of several Swahili and Arab merchants with 200 guards and hundreds of Nyamwezi porters left Bagamoyo and arrived in Kazembe a few months later, among the caravan's leaders was one named Said bin Habib (of ambiguous ancestry38) who travelled through Kazembe and arrived at the Atlantic port of Luanda in 1852 marking the first fully confirmed transcontinental travel in central Africa.39 An audacious journey of more than 4,000 kilometers.

In 1860, Said wrote an account of his travels from Bagamoyo to the cities of Luanda and Benguela. Said —who refers to himself as an ivory trader— described the Kazembe's domains as such "The people appear comfortable and contented, the country is everywhere cultivated, and the inhabitants are numerous, The Cazembe governs with mildness and justice, and the roads are quite safe for travellers", he continues narrating the his travelogue across Lunda-Kazembe territory, passing through the town of Katanza (katanga) near the copper mines, to the Kololo regions of Ugengeh (Jenje), to Lui (Naliele ) and then to Loanda (Luanda). 40

The British “explorer” David Livingstone would later use a similar route as Baptista and Said and make many “discoveries” along the way.

Lunda’s successors: The Chokwe traders and Yeke kingdom.

By the 1870s, the already tenuous central control in the Lunda-Kazembe gave way to centrifugal forces, after a series of succession disputes in which rival contenders to the Lunda throne used external actors to exert their power, and led to the disintegration of the empire. Prominent among these external actors were the Chokwe ivory hunters who were initially used as mercenaries by rival Lunda kings, but later established their own commercial and political hegemony over the Lunda and overrun its capital in 1887. 41

Parts of Lunda fell to King Msiri who used his Nyamwezi allies and Ovimbundu merchants to establish his own state of Yeke over Kazembe and the territories just north of the Lunda domains, and dealt extensively in copper trade, producing nearly 4 tonnes of copper each smelting season.42 Msiri retained most of the Lunda’s administrative apparatus and offices and greatly expanded the long distance copper and ivory trade in both directions; to the Swahili coast and to the Angolan coast using the Nyawezi and Ovimbundu intermediaries.43

By 1875, Nyamwezi caravans were a regular sight in the Angola colony at the coast.44 completing the linking of the Eastern and Western halves of central Africa.

The various states that succeeded the Lunda were largely geared towards cross-continental trade, with a significant expansion in the merchant class especially among the Ovimbundu45 and the chockwe46 . The volume of trade expanded as more commodities such as rubber and beeswax were added to the export trade47.

The Lunda’s successor states were however still in their formative stages when the region was occupied by colonial powers and the dynamic nature of political and economic transformation happening throughout that period was largely described through the context of colonial conquest.

18th-19th century copper ignots from Katanga. According to information relating to the 19th century, miners were paid 3 copper crosses weighing 20kg per trading season while titleholders received about 100kg, with a total of 115 tonnes of copper circulating in payments and tribute every year.48

Conclusion: International trade in Central Africa.

The Trans-continental central African trade which connected the Indian ocean world to the Atlantic ocean world, was largely the legacy of the Lunda state whose rulers linked the long-distance routes across the region, and ushered in an era of economic and political transformation. Contrary to the framing of central Africa as the "undiscovered continent" popularized in colonial literature and travelogues like David Livingstone's, the networks and routes these explorers used were created by and for the Lunda, and were known in internal (African) written accounts more than half a century before Livingstone and his peers "discovered" them.

Despite the tendency to view the nature of the external commodities trade through the 'world systems' paradigm that relegates central African states to the periphery exploited by the western "core", the Lunda's commercial initiative contradicts such theories, it engaged the international markets on its own accord and controlled all stages of production and exchange, it initiated and terminated trade alliances, and it managed trade routes and controlled production.

As the historian Edward Alpers puts it "the long distance African trader in Central Africa was a shrewd businessman, keenly aware of the market in which he was operating" .49 It was through Lunda’s policies and the efforts of long-distance traders that Central Africa was commercially linked from coast to coast, and the region integrated itself into the global markets.

Said Habib was one of many 19th century Swahili travelers who wrote about their journeys, others like Selim Abakari went as far as Germany and Russia, read about Selim’s ‘exploration of Europe’ on Patreon

Contribute to African History Extra through Paypal

A History of West Central Africa to 1850 by John K. Thornton pg 217-221)

Slaves, Spices and Ivory in Zanzibar by Abdul Sheriff pg 192)

Carriers of culture by Stephen J. Rockel, The role of the Yao in the development of trade in East-Central Africa by Edward Alter Alpers

Carriers of culture by Stephen J. Rockel pg 12-23

Reinterpreting Exploration: The West in the World by Dane Kennedy

Copper, Trade and Polities by Nicolas Nikis & Alexandre Livingstone Smith pg 908)

A History of West Central Africa to 1850 by John K. Thornton pg 222-226)

A History of West Central Africa to 1850 by John K. Thornton pg 230)

A History of West Central Africa to 1850 by John K. Thornton pg 234-235, 269-270)

Central Africa to 1870 by David Birmingham pg 112)

A History of West Central Africa to 1850 by John K. Thornton pg 312-313)

A History of West Central Africa to 1850 by John K. Thornton pg 270-271, 320-321)

European Powers and South-east Africa by Mabel V. Jackson Haight pg 92)

The role of the Yao in the development of trade in East-Central Africa by Edward Alter Alpers pg 141

European Powers and South-east Africa by Mabel V. Jackson Haight pg 93)

European Powers and South-east Africa by Mabel V. Jackson Haight pg 92, The role of the Yao in the development of trade in East-Central Africa by Edward Alter Alpers pg 142

European Powers and South-east Africa by Mabel V. Jackson Haight pg 94-95)

The role of the Yao in the development of trade in East-Central Africa by Edward Alter Alpers pg 240-1

Ivory and Slaves in East Central Africa by Edward A. Alpers pg 164),

Kilwa: A History of the Ancient Swahili Town with a Guide to the Monuments of Kilwa Kisiwani and Adjacent Islands by John E. G. Sutton

European Powers and South-east Africa by Mabel V. Jackson Haight pg 94)

European Powers and South-east Africa by Mabel V. Jackson Haight pg 96)

Ivory and Slaves in East Central Africa by Edward A. Alpers pg 246

European Powers and South-east Africa by Mabel V. Jackson Haight pg 97,244)

European Powers and South-east Africa by Mabel V. Jackson Haight pg 99)

The Cambridge History of Africa, Volume 6 pg 81, A History of West Central Africa to 1850 by John K. Thornton g 337)

see full text of their travel account in “The Lands of Cazembe: Lacerda's Journey to Cazembe in 1798” pg 203-240

Portuguese Africa by James Duffy pg 191, European Powers and South-east Africa by Mabel V. Jackson Haight pg 97

Ivory and Slaves in East Central Africa by Edward A. Alpers pg 180,“The Lands of Cazembe: Lacerda's Journey to Cazembe in 1798” pg 188

The Rainbow and the Kings By Thomas O. Reefe, Thomas Q. Reefe pg 172)

Ivory and Slaves in East Central Africa by Edward A. Alpers pg pg 180)

Making Identity on the Swahili Coast By Steven Fabian pg 80-96, 50

The Island as Nexus by Jeremy Presholdt pg 321

Carriers of culture by Stephen J. Rockel pg 224

A History of West Central Africa to 1850 by John K. Thornton pg 311, 317-318)

There are earlier accounts of Swahili traders in the late 18th century undertaking a similar crossing.

Travels, Researches, and Missionary Labors by krapf pg 350)

Said is often called “Arab” with the quotations) in most accounts but it was a rather mutable social category due to the nature of identity in 19th century swahili cities (see my previous article)

Carriers of culture by Stephen J. Rockel pg 51)

“Narrative of Said Bin Habeeb, An Arab Inhabitant of Zanzibar” in Transactions of the Bombay Geographical Society 15 pg 146-48)

Heroic Africans by y Alisa LaGamma pg 187)

The Rainbow and the Kings by Thomas O. Reefe, Thomas Q. Reefe pg 173)

Africa since 1800 By Roland Oliver, Anthony Atmore pg 80, Chasseurs d'ivoire: Une histoire du royaume Yeke du Shaba By Hugues Legros

The Cambridge History of Africa, Volume 5 pg 247

Trade and Socioeconomic Change in Ovamboland, 1850-1906 by Harri Siiskonen

Cokwe Trade and Conquest in the Nineteenth Century by Joseph C. Miller

Terms of Trade and Terms of Trust by Achim von Oppen

Kingdoms and Associations: Copper’s Changing Political Economy during the Nineteenth Century David M. Gordon pg 163

The role of the Yao in the development of trade in East-Central Africa by Edward Alpers pg 55)

Thank you for this interesting article.

Well articulated with facts, maps and references.