War and peace in ancient and medieval Africa: The Arms, Amour and Fortifications of African armies and military systems from antiquity until the 19th century.

Its nearly impossible to discuss African military systems and warfare without first dispelling the misconceptions about African military inferiority which is often inferred from the seemingly fast rate at which the continent was colonized by a handful of European countries in the late 19th century. In truth, colonization itself had for the preceding four centuries been kept at bay after a series of crushing military defeats that African armies had inflicted on early European incursions; most notably along in west-central Africa at the battle of Kitombo in1670. Even going back to the to the medieval era, African states such as Makuria and Aksum had not only kept their independence in the face of formidable Eurasian powers (eg the battles of Dongola in 642/652 when the Nubians defeated the Rashidun caliphate twice) and also managed, in the case of Aksum, to project their power onto another continent establishing colonies in Yemen in the 3rd and 6th centuries. Going even further back, the stereotype of a weak kingdom of Kush is easily dispelled not only by Kerma's military subjugation of 17th dynasty Egypt, but also Kush's extension of its power over both Egypt and parts of Palestine; ruling as the 25th dynasty, including assisting the kingdom of Judah against Assyria, an action which earned Kush praise in the bible; all this rich African military history is conveniently erased with reductive explainers such as the supposed disinterest that foreigners had for Africa which again is easily contested by the expenditure Portugal invested in sending hundreds of its soldiers to their graves on African battlefields like at the battle of Mbanda Kasi in 1623 that reversed portugal’s initial success of conquering Kongo, or the decisive battle of kitombo where Portuguese soldiers were slaughtered by the army of the Kongo province of Soyo and were expelled from the interior of west-central Africa for two centuries, or when Portugal faced off with Rozvi king Changamire at the battle of Mahungwe in 1684 that saw them expelled from the south-east African interior for a century and a half. Not forgetting to mention Africa’s non-European foes such as the Ottoman-Funj wars and the Ottoman-Ethiopian wars, etc that ended in African victory and continued African independence at a time when much of the Americas and parts of southeast Asia where under the heel of European colonialism. It was also not disease that kept invaders out but defeat; its for this reason that Europeans were relegated to coastal forts for which they paid rent to adjacent African states and were often vulnerable to attacks from the interior something that Dahomey’s and Asante’s armies occasionally did to coastal forts.

Support AfricanHistoryExtra by becoming a member of our Patreon community, subscribe here to read more about African history, download free books, and keep this newsletter free for all:

The most damage these misconceptions create is overlooking a very complex history of internal African warfare that is often dismissed as “tribal clashes” despite involving large states with millions of citizens, and armies of tens of thousands of well-trained, well-armed, soldiers that fought; like all states do, for control and defense. Not forgetting the sophisticated battle plans, individual combat abilities, excellent swordsmanship and horsemanship skills; of which they were regularly trained in mock battles, developing unique martial art traditions that impressed and intimidated observers. Another misconception is that of a "Merrie Africa” whose societies were largely egalitarian and peaceful and whose encounter with violence was only foreign, this seemingly well-intentioned misconception has no merit however; African states, like states everywhere, flourished through a complex mix of diplomacy and warfare, primarily to protect their citizens, secure trade routes and for expansion. warfare was almost exclusively a state monopoly, as historian John Thornton writes: "war was overwhelmingly the business of state and Africa was a land of states, if we use the term state to mean a permanent institution that claims jurisdiction over people and sovereignty over defined areas of land, creates and enforces laws, mediates and if necessary settles disputes and collects revenue. Declaring war, calling up armies, and maintaining or controlling the forces so deployed were the business of state, and made war in Africa quite unlike the spontaneous and short-lived affairs often associated in anthropological literature, or Hollywood depictions, with primitive wars.1

Setting aside these reductive theories about Africa’s military past, lets look at the history of warfare in Africa beginning with some select depictions of African warfare by African artists, which will then inform our understanding on the African armies, weaponry, armour and fortifications.

Depictions of African warfare by African artists

While depictions of warfare in African art weren't a very common theme, there are nevertheless a recurring feature in African paintings, engravings, sculpture and illustrations. Some of the most elaborate depictions of war scenes are included among the art catalogues of the of the bronze plaques of Benin, the paintings and miniature illustrations of Ethiopia, the paintings and engravings of Kush, as well as sculptures from the kingdoms of Ife, Asante, Kuba, Loango, and many other African states, plus the "djenne terracottas" of the medieval empires of west Africa.

In these artworks, African artists represented various battle scenes often emphasizing the following; individual participants such as kings, military commanders and other high-ranking officials; the different types of military units/divisions such as cavalry, infantry; the different weapons used in combat; the various types of armor such as helmets, shields, cloth armor and chainmail; the logistics and modes of transportation such as horses and donkeys; other miscellaneous items of war such as drums and trumpets; plus attimes the topography of the battle scene.

Benin war plaques

16th century Benin plaque depicting a war scene (boston museum: L-G 7.35.2012)

16th century Benin plaque depicting a war scene (british museum: Af1898,0115.48 )

description of the first plaque;

"A Benin war chief pulls an enemy from his horse and prepares to behead him. The enemy, identified by the scarifications on his cheek, has already been pierced by a lance. The war chief and the enemy, the focus of the scene, are depicted in profile, while other figures appear frontally: two smaller enemies (one hovers above the action, the other holds the horse) and three Benin warriors—one with a shield and spear, one junior soldier playing a flute, and one playing a side-blown ivory trumpet."

description of the second plaque;

"Depicts battle scene with three Edo warriors accompanied by a hornblower and emada figure, both at smaller scale. Mounted foreign captive with second captive kneeling above. Central high-ranking warrior, second warrior behind, and hornblower wear helmets of crocodile hide, leopard's tooth necklaces, quadrangular bells, leopard's face body armour, bracelets, and wrap-around skirts. Central warrior carried umozo sword in right hand and holds captive with left. the second warrior carries shield in left hand and short spear in right. Third warrior is similarly dressed but with tall helmet decorated with cowrie shells. Emada figure has shaved head with plaits at either side, naked except for baldric attached to sword and girdle. Holds ekpokin box in both hands. Captive on horseback in profile, with facial scarification, wears domed helmet and leopard skin body armour. Spear through back and separate spear at side. Second small scale foreign captive above, kneeling and in partial profile. Facial scarification, wears peaked helmet, and carries sword on left hip. Hands bound with separate bundle of arrows in front"

Ethiopian war paintings and illustrations

Miniature illustration of a contemporary battle scene in the manuscript titled "revelation of st john" (or 533, British library)

Ethiopian Painting on cotton depicting the Battle of Sagale, (British museum: Af2003,19.2,)

In the illustration, the miniature depicts a battle scene drawn in the gondarine style; in the upper half of the illustration, two men armed with the typical Ethiopian spear and shield are shown felling a rifleman; while the bottom half of the illustration depicts two men on horseback carrying spears advancing towards a figure standing in a field of dead bodies carrying a shield and holding a spear2

The painting depicts the succession battle between the supporters of Empress Zewditu, led by Habte-Giyorgis and Ras Tafari, against the supporters of the uncrowned emperor Lij Iyasu, led by Negus Mikael, depicted are the victors; the empress and the Ras Haile Selassie' forces on the left side and the Negus Mikael forces on the right side plus St. George and the Abuna (patriarch), weapons shown include the machine gun, several cannons, swords and the nobility on horses

African armies and warfare

map of African states in from the medieval era to the late 19th century (with the 20°N, 10°N, and 30°S latitudes sketched over)

African weaponry and armies were dictated by; their environment; the resources which individual states could muster (in-terms of demographics, ability to manufacture and repair weapons, the logistical capacities, etc), and lastly, the regional threats (within Africa) and external threats such as the north African, Arabian and European incursions.

In the Sahel and savannah regions between latitudes 10º and 20º north of the equator (which i will be referring to as the middle latitudes since “Sudanic” and “Sahelian” can be quite confusing), the tsetse free environment, relatively flat terrain and sparse vegetation supported horse rearing which greatly improved the mobility of the army, it is thus unsurprising that this was where the majority of Africa's large empires were found since the improved logistics allowed such states to control vast territories; only one of the about twenty pre-colonial African states that exceeded 300,000 sqkm was located outside these longitudes.

Horses were present in this region by the late 2nd millennium in Nubia, and around the end of the first millennium in both west Africa3 and the horn of Africa. Armies often had three divisions with the cavalry as the most prestigious division , serving as the main striking force which varied in size from between 20-50% of the armies of Mali, Songhai4 and Ethiopian empires5 to close to 90% of the army in the Kanem empire. The cavalry was at times augmented by "camel corps" that had a much further reach than horses enabling Songhai troops to strike a far north as Morocco6 and Kanem troops to strike into the Fezzan in southern Libya7.

bornu horsemen in the early 20th century

The next army division was the infantry which often formed the bulk of the army and its use and effectiveness was defined by the weapons they used, personal skills in combat and the state’s demographics; with the Songhai and Ethiopian armies mustering as many as 100,000 soldiers as by the 16th century. In antiquity the infantry were primarily archers such as the famous archers of the kingdoms of Kerma and Kush, plus the "pupil smitters” of the kingdom of Makuria. Later, these infantry were primarily swordsmen and spearmen (or at times pikemen) such as in the armies of Amda Seyon in medieval Ethiopia8 and the Sokoto armies9 , these later incorporated units of musketeers the earliest of which were used in the 16th century notably in Mai Idris' Kanem empire10, and in Sarsa Dengel’s Ethiopian empire and Sarki Kumbari

armies of Kano in the 18th century11

The third army-division was the navy, while the middle latitude wasn't well watered, it was nevertheless dominated by the mostly navigable Senegal and Niger river systems in west Africa, the Nile river in Sudan, plus the red sea and the indian ocean, and thus necessitated the need for navies. In antiquity, such navies consisted of a vast fleet of ships such Akum's 100-ship fleet that carried close to 100,000 soldiers in its invasion of Yemen12 as well as the Ajuran fleet (in the Ottoman-Ajuran alliance) that battled with the Portuguese in the eastern half of the Indian ocean. But since most of the African states were land based, their navies were of river fleets in very large canoes that were originally paddled or oared and at times included those powered by two sails eg in the senegambia13, west African navies in particular were quite formidable, successfully defeating several European incursions from the mid 15th to mid 17th century14.

In the lower latitudes between 10º north and 30º south of the equator, most of the environment is tropical characterized by dense forest or forested savannah, while this region wasn’t suitable for horse rearing because of the tsetse fly, it was fairly densely populated and well-watered with several river systems in the regions of west Africa, west central Africa and the "African great lakes region", added to this were navigable coastal waterways which enabled the growth in maritime cultures of the east African coastal civilizations such as the Swahili, Comorians and Malagasy allowed for the development of a fairly advanced navies, while the open grasslands of central Africa allowed for the formation of vast states such as the Lunda empire.

Armies in these latitudes were mostly divided into infantries and navies, because of the primacy of infantry warfare in these regions, the military systems were often fairly bureaucratic such as in Benin, Kongo, Dahomey and Asante armies who maintained a complex mix of conscript and professional soldiers, and the dense population enabled medium sized states to maintain large armies numbering as many as 100,000 for Asante in the mid-19th century, the navies were fairly sophisticated as well especially in eastern Africa, the need to safeguard extensive maritime trade routes necessitated the deployment of armies on sea, with early wars such as when Kilwa seized Sofala from Mogadishu in the 13th century, and the Comoros-Sakalava wars which involved thousands of soldiers fighting at sea and transported to land attimes using the Swahili ships.

a non-combat mtepe ship

The main units of infantry initially consisted of archers, later including spearmen and swordsmen especially in the armies of the Zulu, Kongo, and the Swahili, these were soon augmented by musketeer units as early as the 16th century notably in Kongo, and Wyddah but by the 17th century, soldiers armed with guns constituted the bulk of the army such as the Asante, Dahomey and Kongo's armies and by the 18th century, virtually all African armies of the Atlantic side were completely armed with guns15

For marine warfare, the navies in west and west-central Africa used medium sized watercraft that could carry upto 100 people, while these were primary used as troop carriers, battles at sea, on lakes and near the coast weren't infrequent, in some cases including mounted artillery on the watercrafts of Warri, Allada and Bonny16 , in eastern Africa, the navies were also used as troop carries and for coastal defense, the latter was especially necessary for the Comorians to repel notorious Sakalava incursions and the Sakalava had large armies of upto 30,000 men that were carried on large canoes17, they engaged in fierce naval battles including one where they were defeated by combined Swahili-Omani fleet in 1817 that was fought at sea using the typical square-sail powered ships of the Swahili18In the 18th century, the army of Pate mounted cannons on Swahili ships to attack the Amu on the Kenyan coast.

African arms, training and manufacture

African arms from antiquity to the early modern era included a variety of missile weapons and combat weapons, the most common missile weapons being arrows, javelins, lances, and guns while the most common combat weapons were daggers and axes, swords.

Training in the use of such weapons was undertaken regularly especially for professional units such as the the mounted soldiers of the hausa (and other central sudanic armies of the Kanem and Bagirmi) whose durbar festivals involve mock battles and showcases of horsemanship19 The swordsmen were trained as well such as in the Ndongo armies who were often practiced mock combat warfare20 and similar training in Asante swordsmanship developed into a unique form martial arts called akrafena and in south eastern Africa, the war dances of the Zulu involved mock battles as well21, later on by the 18th century, armies such as the Alladah, conducted parades and drills with muskets.22

Durbar festival in northern Nigeria

Descriptions of African weapons

Missile weapons.

Arrows, javelins and lances were for most of antiquity and the early medieval era the primary missile weapon; the legendary archers of Kush were renown since old kingdom Egypt and the depictions of the Kerma army in the 16th century BC included several carrying bows, this prominence of archers continues through successive kingdoms of ancient and medieval Nubia especially Makuria In the 7th century whose archers' accuracy in their defeats of Arab invasions earned them the nickname 'the pupil smitters'. In most of west Africa and west-central Africa, battles begun with archers showering down arrows down onto enemy targets eg; Songhay's conquest of Djenne in 1480 begun with such and the Portuguese invasion in senegambia was defeated with these same arrows whose poisoned tips only needed to hit any part of the body and ultimately assured the death of an enemy foe better than musket fire. This was then followed by cavalry charges but oftentimes by an assault from the infantry both of whom wielded javelins and lances the former of which they threw within the course of the battle. While most armies near the Atlantic had adopted guns by the 18th century, the restriction of gun sales to the interior meant most sahelian armies in west Africa used lances and arrows even in the 18th century but their effectiveness wasn't undermined by this absence of guns; Segu armies and Tuareg armies who were primarily armed with such successfully defeated the Arma musketeers several times in the 18th century. In the horn of Africa, arrows were less common, so javelins and lances were the main missile weapon in Ethiopian and surrounding armies, while in south east Africa, Rozvi and Mutapa armies were renown for their archery

Swords

These was the primary weapon of close combat across virtually all African armies; in west-Africa, west-central Africa, eastern Africa and the horn, the swords of various African armies include the ida sword of Benin, the akrafena sword of the Asante, the takuba sword of the sahelian groups (Tuareg, Hausa, Fulani, etc), the kaskara sword of Sudan, the shotel sword of the Ethiopians, the upanga sword of the Swahili, and the various swords of west central africa like the kongolese and loango swords.

16th-19th century sword from the kingdom of kongo (brooklyn museum)

Guns

The majority of guns in west Africa and west-central Africa from the 15th century were muskets (smooth-bore muzzle loaders) until the introduction of breech-loading rifles in the late 19th century, the former were initially matchlocks, followed by wheel-locks then flintlocks. Muskets and cannons were first used in Kongo, Benin, Ethiopia, and Kanem in the the early 16th century23, soon after becoming the primary weapon Atlantic west Africa, but restricted supply across in the interior meant that guns appeared infrequently. In the horn, guns were likely first used in 1527-1540 during the Abyssinia-Adal wars in which the Adal armies armed with several cannons and Turkish muskets, briefly conquered much of the empire24 from then, Ethiopia became a big importer of arms and so did several states in the horn eventually developing the ability to manufacture some arms by the mid 19th century, while in eastern and southern Africa, guns were first used in the 16th century by the Swahili soon after the Portuguese sack of Kilwa and Mombasa although most cities armies were primarily armed with swords, guns would later reach the interior in suffice numbers in the early 19th century where the Nyamwezi king had around 20,000 in his arsenal25

Weapons Manufacture

the manufacture of these weapons involved considerable resources especially iron; eg; a horseman in the senegambia region required a sword, a broad-bladed spear, and seven or eight smaller throwing spears, not including the horses' bits, which in all weighed about 2kg, with an estimated 15,000 of such horsemen for the region needing at least 30 tonnes of iron annually, not including the much larger infantries that doubled this figure26 to produce such weapons required alot of well organized and skilled labor especially blacksmiths; in west Africa, the blacksmiths were numerous and worked in closely organized guilds, forging the hundreds of thousands of lances, swords and arrowheads which were then stored in royal armories,27 in southern Africa during Zulu king Cetshwayo’s reign "zulu blacksmiths would be as busy as any European munitions factory in the time of war, forging assegais by the thousand"28 , Across various African states, arrowheads, helmets, cloth, lances, javelines, axes and other weapons were locally manufactured so too were swords although high ranking soldiers used foreign made swords, at times inscribed with the names of their wielders eg the kaskara swords of the Darfurian and Mahdist armies.

When majority of African armies on the Atlantic-side and in the horn were armed with guns, the biggest requirement was the need for their repair and attimes their manufacture, eg in Zinder in 1850s, where; gunpowder, muskets, cannon mounted on carriages, and projectiles were manufactured locally, equipping its army with 6,000 muskets and 40 cannon29, In Asante, guns were repaired and brass blunderbusses were manufactured30, in eastern Africa, in the mid 19th century, the Ethiopian emperor Tewodros used foreign missionaries to build him a large cannon called sebastopol and several other smaller cannons and guns31

Tewodros’ sebastopol

Transport and Logistics of African armies

As African armies were often fairly large numbering 15,000-100,000, and fought at considerable distance from the place of recruitment in a region that was sparsely inhabited, the logistical and provision challenges they were faced with were significant requiring them to devise several ways to solve this;

The armies in the middle latitude made extensive use of draught animals such as mules, donkeys, camels, oxen and camels, in medieval Ethiopia, soldiers were obligated to bring a donkey with them, they also took with them servants or family members who carried their provisions for the duration of war32 , in the lower latitudes where such animals were less common, porterage was used instead; in Dahomey as many as 10,000 people carried the provisions and baggage of an army about a third smaller, while in Kongo, conscripts and soldier's wives carried the army provisions forming a baggage train stretching for considerable distance at the back of the army, in eastern and southern Africa, the Zulu armies had their provisions carried named izindibi.

Types of African Armour

The cavalry armies of the armies in the middle latitudes were often fitted with quilted cotton arrow-proof armor and chainmail, and the warhorses were attimes outfitted with breastplates, the most notable use of such armor was used in the Hausa armies33 and the Ethiopian armies34 such armor was introduced to the the hausa in the 15th century from the Mali empire and was also adopted by the Sokoto armies in the 19th century, other armies with similar armor included the Songhay, Kanem, Wadai, Darfur and Mahdist armies, other armor included iron helmets, shields, saddles, and horse trappings, the armies of Benin and ife wore leather and arrow-proof cloth armor, carried heavy shields and wore helmets, as shown by the 14th century archer from jebba, large shields were also used in west-central Africa and south eastern Africa in the armies of Kongo, Mutapa and the Zulu.

Quilted armour of the Mahdiya from the 19th century, sudan

African Fortifications

Extensive use of fortifications was a feature of static African warfare in all regions; the construction of which varied according to a given society's architectural traditions and frequency of warfare. These included high enclosure walls some reaching upto 30ft, the ditch and rampart system which was often had enclosure walls at its crest; fortresses for garrisoning soldiers, castle-houses, stockades and palisades, etc. Both permanent fortifications such as walled cities and temporary field fortifications such as fortified war camps existed across Africa especially in the middle latitude regions; present as early as the kingdom of Kerma where one of the earliest buildings in the capital city of Kerma was a square fortress 80x80m built in 2500BC, the entire city of Kerma was also surrounded by an elaborate system of defensive enclosure walls with projecting bastions, and very thick walls, the inside of the city itself contained several forts which served as military barracks35. this fortification tradition was developed intensely in the kingdom of Kush and later in the kingdoms of Christian Nubia where the nearly impregnable fortress of Old Dongola forced the Arab invaders to retreat in 652, and the Nubian castle-houses of the late medieval and early modern era served to protect small settlements in the middle Nile region.

late medieval fortress at el-khandaq in sudan

In the horn of Africa, fortress consisted of both the permanent and semi permanent types, of the former, there are the walled cities of medieval Somalia such as Mogadishu and the the interior cities of Nora and Harar; these city walls were built between the 12th and 16th centuries using granite, sandstone or coral-stone36, these enclosure walls were typically over 15ft high, with several gates and watchtowers that made such cities resemble a large fort, while in medieval Ethiopia the earliest fortifications were the mobile royal camps (katama) that were usually semi-permanent (used for a few decades) and constructed with palisades, the fortification systems became more elaborate in the 16th century with the construction of the fortified palace of Guzara by emperor Sarsa Dengel in the 1570s37 although although its unclear whether this castle, or the more famous Gondar castles it inspired, ever served a military function despite their military inspired architecture. Other ethiopian fortresses such as emperor Tewodros' magdala fort were largely built in the medieval style with palisades, taking advantage of the natural geographical features, in the Somali region, fortress building became more extensive in the late 19th and early 20th century most notably the large fort complex at Taleh built by Somali dervish leader Mohammed Abdullah Hassan in the first decades of the 20th century.

the silsilat fort complex at taleh in somaliland

Sahelian westAfrica contained perhaps had the most numerous of the African fortifications, the earliest were the ditch and rampart system of Zilum in the late 1st millennium BC and the enclosure wall of jenne-jeno in the late 1st millennium AD, but it was during the preceding centuries that fortifications became ubiquitous, the formidable mudbrick walls of the Hausa city-states were in place by the 12th century, the fortified cities along the routes of Kanem empire such as Djado, Djaba were in place by the 13th century, while the enclosure walls of Djenne famously defied both Mali and early Songhay assaults until it fell to the later in the 15th century reportedly after a 7 year-long siege. The 17th-19th century was the period of intensive fortress building, the enclosure walls of west-African cities now consisted of both inner and outer walls and enclosed several square miles of residential and agricultural land protecting cities with populations as high as 100,000 in Katsina and Kano, and over 20,000 for dozens of others, even smaller cities and "hamlets" had massive walls with rounded bastions and platforms for archers and gunners. From the senegambia to the southern chad, both internal accounts and explorer accounts described the typical west African city as strongly fortified, surrounded by a high wall with a several bastions and large gates that were well guarded and occasionally shut.

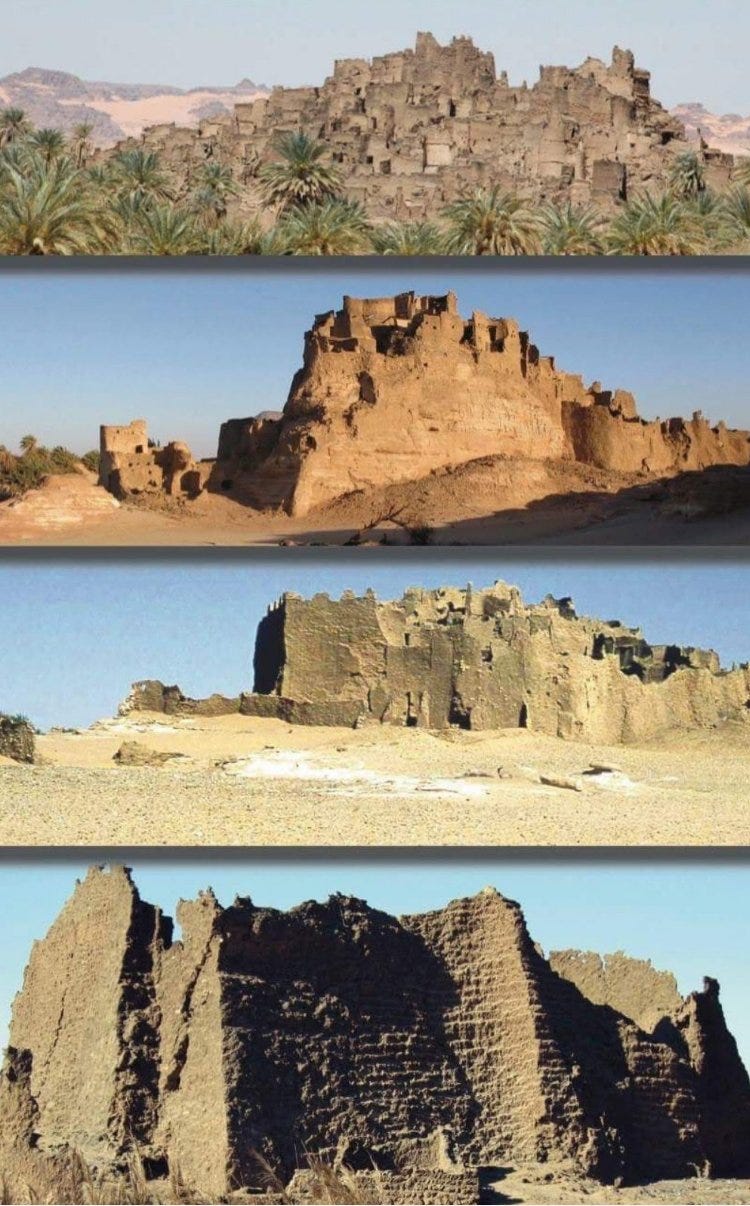

the fortified oasis towns of the kanem empire; djado, djaba, dabassa, seggedim in Niger

the city walls of zinder in Niger

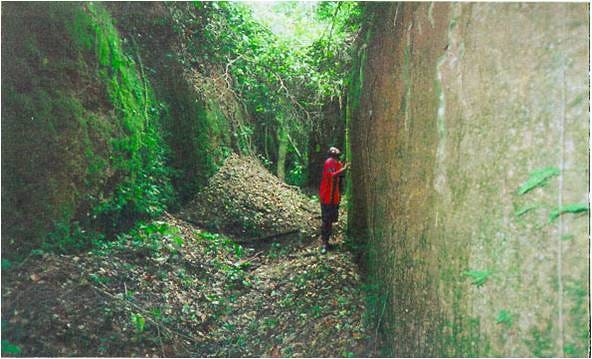

In the Atlantic west Africa and west central Africa, the most most elaborate fortification systems were built in south-eastern Nigeria most notably the rampart and moat system of the city of Benin built between the 13th and 15th century, described as the most extensive man-made earthwork in the world, at the crest of these moats was a high wall made of palisades filled with earth which served as the city wall with several high watchtowers adjacent to the city gates that were guarded with archers and gunners38 this system of digging deep moats and raising earthen walls of palisades at their crests was common in many of the forest region in cities such as Ijebu and Ife, and in the kingdom of Dahomey and Oyo39 and in west-central Africa, the city of Mbanza Kongo was surrounded by a high city wall; 20ft high and 3ft thick, built in stone around 152940 but the most common fortification in this region were the palisades walls such as in the kingdoms of loango and Ndongo.

sungbo’s eredo moats of Ijebu

In eastern and southern Africa, the Swahili, Comorian and northern Madagascar cities were fortified as early as the late first millennium at Qanbalu in Tanzania with high coral-stone walls and several towers at its corners, it was "surrounded by a city wall which gave it the appearance of a castle"41 construction of fortifications increased during the classic Swahili phase (1000-1500AD) the typical Swahili city such as Shanga, Kilwa, Gedi, were surrounded by fairly high city walls built with coral-stone. Field fortresses were rare but were also built eg at Kilwa, the Husuni Ndogo fort measuring 100m by 340m was constructed in the 14th century, such fortresses building became more extensive from the 16th to the 19th century especially during the rise of Oman's imperial power along the east African coast, these Omanis and their Portuguese predecessors had built a number of fortresses to secure their possessions, prompting cities such as Mutsamudu in comoros, and Siyu in kenya to construct their own fortresses.42

Fortress of mutsamudu in comoros

In south eastern Africa, the hundreds of Great-Zimbabwe type walled cities have since been interpreted as ostentatious symbols of power rather than defensive fortifications. Despite this interpretation, some of the walled settlements from the Mutapa kingdom eg the hill-forts of Nyangwe and Chawomera, and some of the stone-walled Tswana cities likely served as defensive walls or fortresses.

Fortress defense: Peace in the pre-colonial African warscape.

African armies devised many ways of besieging and taking walled cities and fortresses, including mounting musketeers on high platforms, tunneling under the walls, scaling the walls using ladders, shooting incendiary arrows to raze the interior, drawing out the defenders for pitched battles through various means or settling in for long sieges43 . But in general, the defenders had the advantage over their attackers primarily because the walled cities were often self-sufficient in provisions with enough agricultural land and water; for example in Kano, only about a third of the enclosed territory was built up, the rest being cultivated farmland, and , save for the infrequent use of cannons along the east African coast and in west Africa, the late entry and infrequent use of such artillery in assaulting walled cities meant that the construction of such fortifications became the norm across the various African regions, the fortifications themselves serving as a deterrent from attack.

rampart and ditch of the kano walls

Conclusion

Pre-colonial African military systems defy the simplistic interpretations in which they are often framed, and while their relative military strength is difficult to gauge save for the few that are familiar with African military history, it's quite easy to observe that African military strength compared favorably with the European colonial armies especially during the first (failed) phase of colonization in the 17th century; as Historians Richard Gray44 and John Thornton45 have observed, European colonial armies had no decisive advantage over African armies, neither guns nor naval power nor strategy gave them battle superiority; they were flushed out of the interior and relegated to small coastal enclaves. The second phase of colonization was initially not any more successful for European armies than the first had been, as military historian Robert Edgerton observed; British and Asante forces were initially equally matched in the early 19th century46, it was therefore unsurprising that Asante won the first major battles in its nearly-100 year long wars with the British, but by the close of the century, African armies couldn't match the longer range, rapid fire modern artillery of the Europeans; this wasn’t because Africans had chosen not to acquire them, but they were essentially embargoed from purchasing them especially after the Berlin conference. While firearms didn't offer a significant advantage in the preceding centuries, these modern rifles did, but few African armies were able to acquire them in significant quantities; the most notable exceptions being Menelik's Ethiopian army that had 100,000 modern rifles by the time it defeated the Italians at Adwa (the same rifles he had ironically bought from them a few years earlier), this arsenal had been rapidly built up after Tewodros' disastrous defeat by the British in 1868. African armies strength must also be weighed against the less-than-favorable demographics of the late 19th century when the entire continent had about as many people as western Europe, yet despite this Africans didn't simply sign off their land for trinkets is commonly averred, rather, they rallied their troops time and again in fierce battles to defend their home; the list of colonial wars is endless (besides the better known ones i mentioned that were fought by large states) and this "martial spirit" of Africans continued well into the colonial era and saw at least five African countries fighting their colonial powers in protracted wars, ultimately winning their independence (these include; guinea Bissau, Angola, Namibia, Zimbabwe and Mozambique).

African military history should therefore not be understated in understanding both African history and modern African politics.

for more on African history, please subscribe to my Patreon account

Warfare in Atlantic Africa, by J. Thornton, pg 15

secular themes in ethiopian ecclesiastical manuscripts by Pankhurst, pg 47)

The Archaeology of Africa by Bassey Andah, pg 92

J. Thornton, pg 27

church and state by T. Tamrat, pg 93

Timbuktu and the songhay by J. Hunwick, pg 242)

Warfare & Diplomacy in Pre-colonial West Africa by R. Smith, pg 91

T. Tamrat. pg 94

warfare in the sokoto caliphate by M. Smith, pg 10

R. Smith, pg 82

M. Smith, pg 15

The throne of adulis by Glen Bowersock ,Pg 78,

J. Thornton, pg 29)

Africa and Africans in the Making of the Atlantic World by John Thornton, pg 37-38

warfare in atlantic africa by J. Thornton, pgs 45,63 109

J. Thornton, pg 83-84

Islands in a Cosmopolitan Sea by I. Walker, pg 77-79

Ivory and Slaves in East. Central Africa by E. Alpers, pgs235

The History and Performance of Durbar in Northern Nigeria by Abdullahi Rafi Augi

J. Thornton pg 105

The Annals of Natal: 1495 to 1845, Volume 1, pg 334

J. Thornton, pg. 80

R. Smith pg 82)

Ethiopia's access to the sea, by F. Dombrowski, pg 18-19

Arming the Periphery by E. Chew pg 143)

Africa and Africans in the Making of the Atlantic World, by J. Thornton, pg 48)

R. Smith pg 65

Zulu victory by R. Lock

M. Smith pg 99

The fall of the Asante pg 67

guns in ethiopia by R. Pankhurst pg 28-29

an introduction to the history of the Ethiopian army by R. Pankhurst. pg 7,167

M. Smith, pg 46

R. Pankhurst, pg 5

black kingdom of the nile by C. bonnet pg 11-21, 32-34)

The Archaeology of Islam in Sub-Saharan Africa by T. Insoll, pg 78

Three Urban Precursors of Gondar by R. Pankhurst

The military system of Benin Kingdom by B. Osadolor, pg 119-123

J. Thornton, pg 84-88

Africa’s urban past by R. Rathbone pg 68

Swahili pre-modern warfare and violence in the Indian Ocean by S. Pradines

Siyu in the 18th and 19th centuries by V. Allen

M. Smith pg 111

Portuguese Musketeers on the Zambezi by R. Gray

Early Kongo-Portuguese Relations by J. Thornton

“Britain and Asante: The Balance of Forces” in The Fall of the Asante Empire by R. Edgerton