What were the effects of the Atlantic slave trade on African societies?: examining research on how the middle passage affected the Population, Politics and Economies of Africa

The African view of the Atlantic world.

Debates about Africa's role in the Transatlantic slave trade have been ongoing ever-since the first enslaved person set foot in the Americas, to say that these debates are controversial would be an understatement, the effects of the Atlantic slave trade are afterall central to discourses about what is now globally recognized as one of the history's worst atrocities, involving the forced migration of more than 12.5 million people from their homes to brutal conditions in slave plantations, to live in societies that excluded their descendants from the fruits of their own labor.

Given this context, the climate of discourse on Atlantic history is decidedly against narratives of agency about any group involved in the Atlantic world save for the owners of slave plantations, therefore most scholars of African history are rather uneasy with positions which seem to demonstrate African political and economic autonomy during this era, for fear of blaming the evils of slavery in the Americas on the Africans themselves, despite the common knowledge (and repeated assurances) that the terms "African"/"Black" were modern constructs that were alien to the people whom they described and weren't relevant in determining who was enslaved in Africa (just as they didn't determine who could be enslaved in much of the world outside the Americas). Nevertheless, some scholars advance arguments that reinforce African passivity or apathy without fully grasping the dynamic history of African states and societies, and this may inform their conclusions on the effects of the Atlantic slave trade on pre-colonial Africa.

This article examines the effects of Atlantic slave trade on pre-colonial African states, population and economies, beginning with an overview of debates on the topic by leading scholars of African history and their recent research. I conclude that, save for some social changes in the coastal societies, the overall effects of the external slave trade in west-Africa and west-central Africa have been overstated.

Map of the Transatlantic Slave Trade, 1501–1867 (from Atlas of the Transatlantic Slave Trade by David Eltis)

Support AfricanHistoryExtra by becoming a member of our Patreon community, subscribe here to read more about African history, download free books, and keep this newsletter free for all:

Effects of the Atlantic slave trade on African states: the cases of Kongo kingdom and the Lunda empire, and brief notes of the Asante and Dahomey kingdoms.

Map of west-central Africa in 1750 showing the Lunda empire and Kongo kingdom

Some scholars have often associated the huge number of slaves sold into the trade with major political developments in the interior of Africa, notably with processes of state formation and imperial expansion. They argue that the enslavement and subsequent sale of slaves required such great resources that only rulers who commanded large followers could undertake such activities.

Scholars such as Joseph inikori blame the expansion of slave trading for the collapse of centralized authority in Atlantic Africa; that the "persistent intervention by the European traders, and the vicious cycle of violence from massive slave trading…reproduced fragmentation in many places” and “severely constrained the spread of strong centralized states", citing the case of the Kongo kingdom which he argues had no indigenous institution of slavery prior to the arrival of European traders, and that it was politically "too weak to withstand the onslaught unleashed by Portuguese demand for captives", this he says lead to an internal breakdown of law and order and the kingdom’s collapse. Where centralized states did develop, he attributes their formation to the external slave trade, writing that "no serious attempt to develop centralized states was made until the crisis generated by the slave trade" he cites the cases of Dahomey and Asante, and claims that their "state formation was in part a device for self-protection by weakly organised communities", further arguing that "had strong centralized states like Asante, Dahomey .. been spread all over sub-Saharan Africa .. the balance of power among the states, would have raised the political and economic cost of procuring captives to a level that would have made their employment in the Americas less economic." but this didn’t happen because "european traders consciously intervened in the political process in western Africa to prevent the generalized development of relatively strong large states."1

Others such as Paul Lovejoy, take this argument further by positing a "transformation in slavery" across the African interior as a result of the Atlantic slave trade, which he says resulted in the emergence of African societies ruled by "warlords" perpetuated rivalries that degraded africa’s political development. In west central Africa for example, he argues that the export trade drained population from the productive sectors, concentrating slaves in areas connected with the export trade. The supply mechanism thereby influenced the expansion of a “slave mode of production” across the economy, and that this radical transformation resulted in half the population of Kongo were of servile status. 2

Others, such as Jan Vansina and David Birmingham, in looking at specific cases of African states, argue that the Lunda empire founded by Ruund-speakers, was established by expatriates who had closely interacted with the Portuguese traders of Angola and thus established a large state which extended military activities in the interior in response to the growing demand of slaves, which resulted in the creation of thousands of war captives who were offloaded to slave traders at the coast.3

However, recent research by Domingues da Silva shows that most of the west-central African slaves exported in the late 18th/mid 19th century came from regions and ethnic groups near the coast that were far from the Lunda political orbit which was several hundred kilometers in the interior, and that most of these slaves were kimbundu, kikongo and umbundu speakers coming from the former territories of the then fragmented kingdom of Kongo, as well as the kingdoms of Ngoyo, Kakongo, and Yaka, he thus concludes that the Lunda were responsible for little if any of the external slave trade from west-central Africa in the late 18th century. His research adds to the observations of other scholars such as David Northrup, Ugo Nwokeji, Walter Hawthorne and Rebecca Shumway who argue that the supply of slaves sold on the coast did not necessarily depend on processes of state formation and expansion in the interior, they cite examples of decentralized societies among the Efik, Igbo, and Ibibio in the “Bight of Biafra”, and similar stateless groups in the “gold coast” and in what is now Guinea Bissau that supplied significant numbers of slaves to the external market.4

Map of the west central Africa in the 19th century including the estimated number of slaves leaving West Central Africa by linguistic groups, 1831–18555

The inaccuracies of “victim” or “collaborator” narratives of Kongo political history

As described in the observations by Inikori and Lovejoy, the Kongo Kingdom is often used as a case of the presumed devastating effects of the Atlantic slave trade, one where Portuguese traders are said to have exploited a weak kingdom, undermined its institutions and led to its collapse and depopulation as its citizens were shipped off to the American slave plantations.

The history of the kingdom however, reveals a radically different reality, the Kongo kingdom was a highly centralized state by the late 15th century when the Portuguese encountered it, and the foremost military power in west central Africa with several provincial cities and a large capital. Its complex bureaucracy was headed by a king, and an electoral council that chose the King and checked his powers as well as controlled the kingdom's trade routes.6

Kongo had a largely agricultural economy as well as a vibrant textile industry and copper mining, which supported the central government and its bureaucracy through tribute collected by tax officials in provinces and sent to the capital by provincial rulers who also provided levees for the military and were appointed for 2-3 year terms by the King.7

As a regional power, Kongo’s diplomats were active across west central Africa, western Europe and in the Americas allowing them to influence political and religious events in the Kingdom’s favor, as well as enable it to create military and trade alliances that sustained its wealth and power. All of which paints a radically different picture of the kingdom than the weak, beguiled state that Inikori describes.8

According to Linda Heywood, Ivana Elbl and John Thornton, the institution of slavery and the trade in slaves was also not unknown to the kingdom of Kongo nor was it introduced by coastal traders, but was part of Kongo’s social structure from its earliest formation. These scholars identified local words for different types of slaves, they also used oral history collected in the 16th century, the large volumes of external trade by the early 16th century and documents made by external writers about Kongo’s earliest slave exports to argue that it was unlikely for the Kingdom’s entire social structure to have been radically transformed on the onset of these external contacts.9

Slaves in Kongo were settled in their own households, farming their own lands and raising their own families, in a social position akin to medieval European serfs than plantation slaves of the Americas.10 Internal and external slave trade was conducted under Kongo laws in which the slaves -who were almost exclusively foreign captives- were purchased, their prices were fixed and which taxes to be paid on each slave11. Kongo’s servile population was a consequence of the nature of the state formation in west central Africa, a region with low population density that necessitated rulers to "concentrate" populations of subjects near their political capitals, these concentrated towns eventually grew into cities with a “scattered” form settlement, and were populated by households of both free and enslaved residents.12

Kongo’s textile handicraft industries also reveal the flaw in Lovejoy’s “slave mode of production”. Kongo’s cloth production was characterized by subsistence, family labor who worked from their homes or in specialist villages within its eastern provinces. These textiles later became the Kingdom's dominant export in the early 17th century with upto 100,000 meters of cloth were exported to Portuguese Angola each year beginning in 1611, while atleast thrice as much were retained for the local market.13

As a secondary currency in west central Africa, many of the Kongo textiles bought by the Portuguese and were primarily used to pay of its soldiers (these were mostly African Levées from Ndongo and the Portuguese colony of Angola), as well in the purchase and clothing of slaves bought from various interior states. Its thus unlikely that the export trade in slaves significantly transformed Kongo's social and economic institutions because despite the expansion of textile production and trade in its eastern provinces now, production remained rural based, without the growth of large towns or "slave plantations", and without "draining" the slave population in the provincial cities of the kingdom such nor from the capital Mbanza Kongo which retained the bulk of the Kingdom's population.14

Kongo had several laws regulating the purchase and use of slaves, with a ban on the capture and sell of Kongo citizens, as well as a ban on the export of female slaves and domestic slaves who were to be retained in the kingdom itself, leaving only a fraction of slaves to be exported. Kongo went to great lengths to enforce this law including two instances in the late 16th century and in 1623 when the Kingdom’s officials repatriated thousands of Kongo citizens from Brazil, these had been illegally enslaved in Kongo’s wars with the Jaga (a foreign enemy) and the Portuguese, both of whom Kongo managed to defeat.15

Throughout this period, Kongo's slave exports through its port at Mpinda were estimated at just under 3,100 for years between 1526–1641 and 4,000 between 1642–1807,16 with the bulk of the estimated 3.9 million slaves coming from the Portuguese controlled ports of Luanda (2.2 million) and Benguela (400,000), as well several northern ports controlled by various northern neighbors of Kongo (see map). That fact that the Kongo-controlled slave port of Mpinda, which was active in the 16th and 17th century, doesn't feature among the 20 African ports which handled 75% of all slave exports, provides further evidence that Kongo wasn't a major slave exporter itself despite being the dominant West-central African power at a time when over a million slaves were shipped from the region between 1501-167517, and its further evidence that the internal Kongo society was unlikely to have been affected by the export slave trade.

These recent estimates of slave exports from each African port are taken from David Eltis’ comprehensive study of slave origins and destinations, and they will require that scholars greatly revise earlier estimates in which Kongo’s port of Mpinda was thought to have exported about 2,000-5,000 slaves a year between 1520s and 1570s, (which would have placed its total at around 200,000 in less than half a century and thus exaggerated its contribution to the slave exports).18 Furthermore, comparing the estimated "floating population" of about 100,000 slaves keep internally in the Kongo interior vs the less than 10,000 sold through Mpinda over a century reveals how marginal the export trade was to Kongo's economy, which nevertheless always had the potential to supply far more slaves to the Atlantic economy than it did. And while a counter argument could be made that some of Kongo’s slaves were sent through the Portuguese-controlled port of Luanda, this was unlikely as most were documented to have come from the Portuguese colony of Angola itself and several of the neighboring kingdoms such as Ndongo19, and as I will explain later in the section below on the demographic effects of slave trade, the Angolan slave exports would result in a stagnated population within the colony at a atime when Kongo and most of the interior experienced a steady increase in population.

Map of the major Atlantic slave ports between 1642–1807, and 1808–1867

List of largest Africa’s largest slave exporting ports

The internal processes that led to Kongo’s decline.

Kongo's fall was largely a result of internal political processes that begun in the mid-17th century as power struggles between powerful royal houses, each based in a different province, undermined the more equitable electoral system and resulted in the enthronement of three kings to the throne through force rather than election, these were; Ambrósio I (r. 1626-1631), Álvaro IV (r. 1631-1636) and Garcia II (1641-1660).20

These rulers, who were unelected unlike their predecessors, depended on the military backing of their royal houses based in the different provinces. Their actions weakened the centralizing institutions of Kongo such as its army (which was defeated by the rebellious province of Soyo in several battles), and loosened the central government’s hold over the provinces, as tax revolts and rebellious dukes unleashed centrifugal forces which culminating in the breakaway of Soyo as an independent province. The weakened Kongo army was therefore unsurprisingly defeated in a Portuguese-Angloan invasion of 1665, but the initial Angolan victory turned out to be inconsequential as the Portuguese army was totally annihilated by the Soyo army in 1670 and permanently ejected from the Kongo interior for nearly three centuries.

However, the now autonomous province of Soyo failed to stem the kingdom's gradual descent and further contributed to the turmoil by playing the role of king-maker in propping up weak candidates to the throne, leading to the eventual abandonment of the capital Sao Salvador by the 167821. Each province of Kongo then became an independent state, warring between each other and competing of the control of the old capital, and while the kingdom was partially restored in 1709, the fragile peace, that involved the rival royal houses rotating kingship, lasted barely half a century before the kingdom disintegrated further, such that by 1794 when the maniKongo Henrique II ascended to the throne “he had no right to tax, no professional army under his control”, and had only “twenty or twenty five soldiers,” his “authority remains only in his mind,” as real power and wealth had reverted to the provincial nobles.22

In none of these internal political process was external slave trade central, and the kingdom of Kongo therefore diverges significantly from the many of the presumed political effects of the transatlantic slavery, its emergence, its flourishing and its decline were largely due to internal political processes that were not (and could not be) influenced by Portuguese and other European traders at the coast, nor by the few dozen European traders active in Kongo’s capital (these european traders barely comprised a fraction of the city's 70-100,000 strong population).

The social institutions of Kongo’s former territories were eventually partially transformed in the 18th and 19th century, not as a result of the external slave trade but the political fragmentation of Kongo that begun in the late 17th century, which lead to the redefinition of “insider” vs “outsider” groups who could be legally enslaved, which is the reason why the 18th century map above came to include Kikongo speakers.23 but even after Kongo’s disintegration, the overall impact of the slave trade on Kongo’s population was limited and the region’s population continued to grow as I will explain below.

Examining the founding of Asante and Dahomey within their local contexts.

Map of of west africa in the 18th century showing the Asante and Dahomey kingdoms located in the so-called “gold coast” and “ slave coast”24

A similar pattern of African political autonomy and insulation from the presumed negative effects of the external slave trade can also be seen in other kingdoms, such as the kingdoms of Asante and Dahomey which according to Inikori and other scholars, are thought to have undergone political centralization as a result of slave trade. According to Ivor Wilks and Tom McCaskie however, Asante’s political history was largely dictated by internal dynamics growing out of its independence the kingdom of Denkyira in a political process where external slave trade was marginal, and none of the Asante states’ institutions significantly depended on the export of slaves into the Atalntic.25

Furthermore, Dalrymple-Smith’s study of Asante state’s economic and political history shows that few of the Asante military campaigns during this period were directed towards securing lucrative slave routes, with most campaigns instead directed towards the the gold producing regions as well as trade routes that funneled this gold into the trans-Saharan trade, adding that the gold-coast "region’s various polities in the seventeenth century were always focused on the control of gold producing areas and the application of labour to mining and extraction".26 Making it unlikely that external slave trade or the presumed violence associated with it, led to the emergence of the Asante state in defense against slave-raiders.

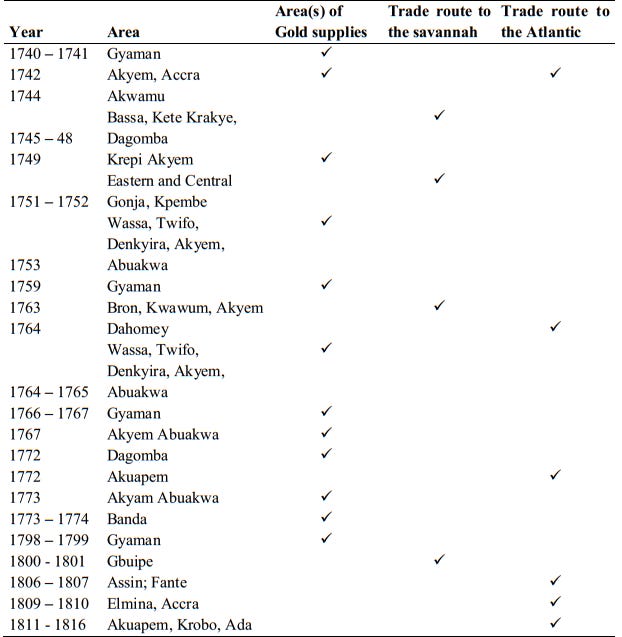

Location of major Asante military campaigns 1740–181627

The Dahomey kingdom, according to the scholars Cameron Monroe, Robin Law and Edna Bay started out as a vassal of the more powerful kingdom of Allada in the 17th century, from which it adopted several political institutions and rapidly expanded across the Abomey plateau in the early 18th century at the expense of its weaker suzerain, before it marched south and conquered the kingdoms of Allada in 1724 and Hueda (ouidah) in 1727.28

Its expansion is largely a result of its rulers successful legitimation of power in the Abomey plateau region through popular religious customs and local ancestor deities, enabling early Dahomey kings to attract followers and grow the kingdom through “the manipulation of local allegiances and overt conquest”29 in which external slave trade was a secondary concern. Dahomey's conquest of the coastal kingdoms in the 1720s led to a drastic fall in slave exports by more than 70% from a 15,000 slaves a year annually in the 1720s to a low of 4,000 slaves annually in the 1780s, leading to some scholars such as Adeagbo Akinjogbin to claim that Dahomey conquered the coast to abolish the slave trade,30 and recently Joseph Inikori who says that "Dahomey invaded the coastal Aja states in the 1720s to bring all of them under one strong centralized state in order to end the slave trade in the region".31

But these observations have been discounted by most scholars of Dahomey history who argue that they are contrary to the political and economic motivations and realities of the Dahomey Kings. For example, Cameron Monroe argues that unlike Dahomey’s interior conquests which were driven by other intents, the objectives of the coastal conquests were largely driven by the control of the external slave trade, despite the rapid decline in slave exports after the fact32, This view is supported by other scholars such as Robin Law who argues that the Dahomey kings wanted to monopolize the trade rather than end it, writing that “although Agaja was certainly not an opponent of the slave trade, his policies tend to undermine it by disrupting the supply of slaves into the interior”,33 and Finn Fuglestad who writes that the theory that "the rulers of Dahomey consciously limited the slave trade, can be safely disregarded" as evidence suggests they were infact preoccupied with restoring the trade but failed because "Dahomeans’ lack of commercial and other acumen" and "the apparent fact that they relied exclusively on their (overrated) military might".34

Robin Law’s explanation for why Ouidah’s slave exports declined after Dahomey’s conquest of the coast shows how internal policies destroyed Dahomey’s slave export trade, he suggests that the increased taxes on slave exports by Dahomey officials, which rose from a low of 2.5% to a high of 6%, and which were intended to restrain wealth accumulation in private hands, forced the private merchants from the interior (who had been supplying between 83% to 66% of all slaves through Ouidah) to shift operations to other ports on the slave coast.35

Yet despite their conquest of the coast in relation to the external slave trade, most of Dahomey's wars weren't primarily motivated for the capture of slaves for export. This view was advanced by John Thornton based on the correspondence between Dahomey’s monarchs and Portuguese colonists in Brazil , who, unlike the British audiences, weren’t influenced by debates between the opposing Abolitionist and pro-slavery camps, and are thus able to provide less biased accounts about the intentions of the Dahomey rulers. In most of these letters, the Dahomey monarchs describe their conquests as primarily defensive in nature, revealing that the capturing slaves was marginal factor; “a given in any war, but rarely the reason for waging it”. Which confirms the declarations made by Dahomey kings’s to the British that “Your countrymen, who allege that we go to war for the purpose of supplying your ships with slaves, are grossly mistaken.”36

Effects of the Atlantic slave trade on Africa’s Population and Demographics

Studies of the trans-Atlantic slave trade's impact on Africa’s population have long been central to the debates on the continent’s historical demographics, economic size, level of ethnic fractionation and state centralization, which they are often seen as important in understanding the continent’s current level of development.

Scholars such as Patrick Manning argue that, the population of West Africa would have been at least twice what it was in 1850, had it not been for the impact of the transatlantic slave trade.37 But Manning also admits the challenges faced in making historical estimates of populations in places with little census data before the 1900s, writing "the methods used for these population estimates rely on projections backward in time" (which typically start in the 1950s when the first true census was undertaken) and to these estimates he makes adjustments based on his assumption about the population effects of the slave trade.38

His findings also diverge from the estimates of Angus Madison who argues for a gradual but consistent increase in African population from the 18th century, the latter's findings were inturn based again on backward projections from the mid 20th century, and his assumption of a more dynamic African economy. Madisson's estimates were in turn similar to John Caldwell’s who also derived his figures from population data on projected backwards from the mid 20th century statistics, and his assumption that African populations grew as a result of introduction of new food crops.39

Nathan nunn who, basing on backwards-projected population estimates and his assumption that the Atlantic trade led to a fall in africa’s population, goes even further and associates Africa’s historical population data with the continent's modern level of development. Using a map of "ethnic boundaries" made by Peter Murdock in 1959, he argues that external slave trade correlates with modern levels of GDP, and one of the measures central to his argument is that parts of africa that were the most prosperous in 1400, measured by population density, were also the most impacted by the slave trade, leading to ethnic fractionization, and to weak states.40

Charts showing the various estimates of africa’s population as summarized by Patrick Manning41, the chart on the right is by Manning as well.42

These speculative estimates of pre-colonial African populations which primarily rely on backwards projection of data collected centuries later, and individual authors' presumptions about the effects of slavery, the level of economic development and the level of food production, have been criticized by other scholars most recently Timothy Guinnane who argues that the measurement errors in their estimates are transmitted from continental estimates to regional estimates and down to individual African countries (or ethnic groups as in Nunn’s case), which leads to a very wide variation in the final population estimates between each scholar. For example, the differences between the implied estimates of Nathun Nunn's figure for Nigeria's population in 1500 to have been 6.5 million, while Ashraf Quamrul estimates it to have been 3.9 million.43

A better approach for those hoping to make more accurate estimates of Africa’s population would be to begin with estimates of smaller regions where data was more available. One such attempt was made by Patrick manning to measure the population growth/decline of the "slave coast" (a region along the west african coast that now includes Benin, Togo and south-western Nigeria), which he estimates suffered a 2- 4% annual population loss in the 18th century, and that this population decline was higher than its rate of natural increase. But his findings have been regarded as "impressionistic" by scholars such as Robin Law, who argues that Manning’s estimates aren’t derived from "rigorous statistical proof", because they were based on assumptions about the original population of the region that he arrived at by projecting the modern population figures backwards.44

Population data from west-central Africa and the demographic effects of slave trade in the coastal colony of Angola.

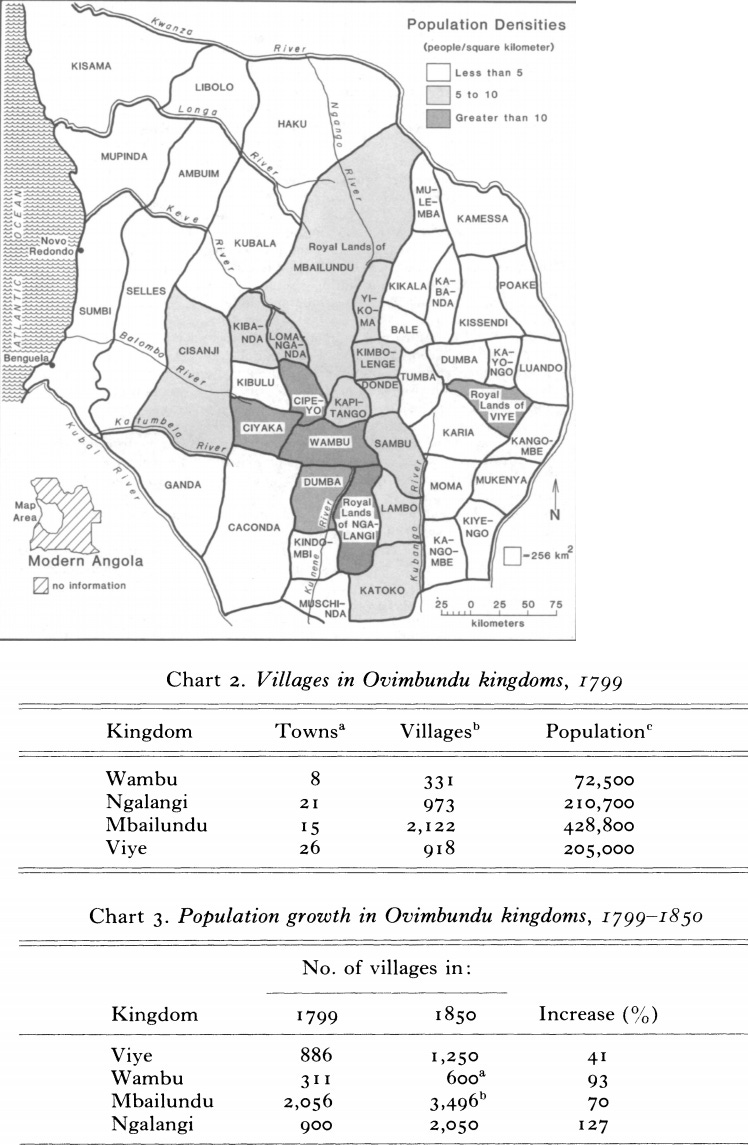

More accurate estimates of pre-colonial African population on a localised level, were made by Linda Heywood and John Thornton in several west-central African regions of Kongo, Ndongo (a vassal of Portuguese Angola) and a number of smaller states founded by Umbundu speakers such as Viye, Ngalangi and Mbailundu. Unlike most parts of Atlantic Africa, west-central Africa had plenty of written information made by both external and internal writers from which quantitative data about pre-colonial African demography can be derived such as baptismal statistics in Kongo, census data from Portuguese Angola and State fiscal records from the Umbundu kingdoms.

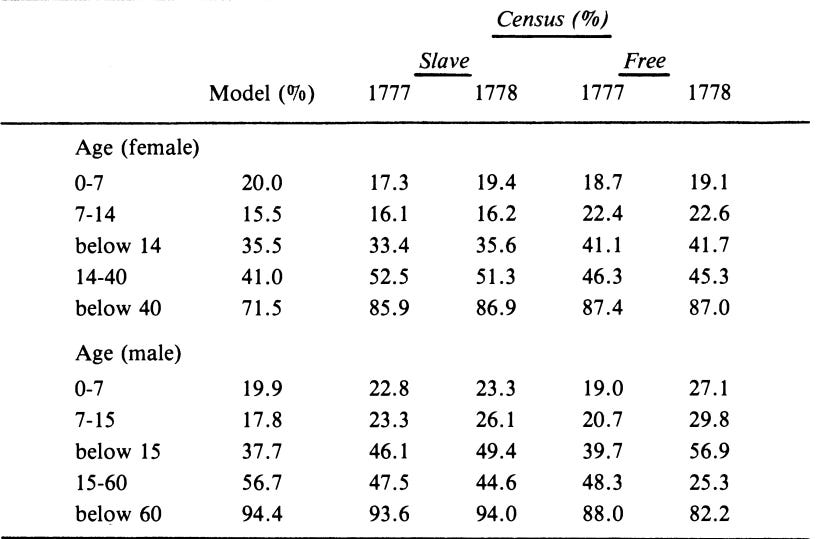

The baptismal records from Kongo come from various missionaries to the kingdom in the 17th and 18th century, the population records of Portuguese Angola come from a census undertaken for the years 1777 and 1778, while the Umbundu population figures were collected by Alexandre Jose Botelho de Vasconcellos in 1799 (based from fiscal information derived from Portuguese officials serving as suzerains overlords of the sobas in the region) and Lazlo Magyar in 1849 (based on fiscal records of several Umbundu states and the neighboring Lunda empire, both of which he resided for a long period).

The data collected from all these regions shows that the population density of Kongo (in what is now north-western Angola) varied between 5-15 people per square kilometer between 1650 and 1700 with the kingdom's population growing from 509,000 to 532,000 over half a century, which reveals that Kongo's population was much smaller than the often cited 3,000,000 people (and the presumed 100 per skq kilometer), but it also shows a steady population increase at a rate close to the contemporary global average, which eventually grew to just under a million by 1948.45

Map showing the population density of Soyo in 1700, and a chart showing the Population distribution of Kongos provinces between 1650 and 170046

Population data from the Umbundu kingdoms (in what is now central Angola), shows that the population density was 5-10 people per square kilometer between 1799 and 1850 and that the total population across the kingdoms grew by 41%-127%. Data from the Lunda empire (in what is now western Angola and southern D.R.C) shows its population density was 3-4 people per sqkm.47

Map showing the population distribution of the Umbundu states in central and charts showing the population distribution and population growth of the region’s various kingdoms.48

Population data from the Portuguese colony of Angola (located south of Kongo, and west of the Umbundu states see the map of west-central Africa in the introduction) had a population growth rate of 25.7 per 1,000 and a gender ratio heavily skewed towards women in the years between 1777 and 1778, with an annual population increase of around 12,000 which was dwarfed by the 16,000 slaves exported through region each year, although some of these slaves would have come from outside the region and he adds that the gender ratio its likely a result of female slaves being retained and thus suggests the colony’s population may have been stagnant or slightly increasing 49 (a conclusion supported by Lopes de Lima, a colonial official in 1844 who, basing on census data he consulted, observed that the colony’s population had barely grown by 1%50)

Table of Angola colony’s census data for 1777 and 1778, showing proportions of people younger than specific ages, within certain age categories, for each gender , as obtained from both the census and the model life table.51

These studies therefore show that the export slave trade had a much lower impact in parts of west-central Africa than is commonly averred despite the region supplying the largest number of slaves to the Atlantic.

Furthermore, considering that the territories of the former Kongo kingdom where an estimated 6,180 slaves were said to have been derived/ passed-through annually in the years between 1780 and 1789; this amounts to just 1% of the region’s 600,000 population,52 and in the Umbundu kingdoms where 4,652 slaves were said to have been derived/ passed-through annually between 1831 to 1855; this amounts to just 0.3% of 1,680,150 population.53

Given the importance of west-central Africa as the supplier of nearly 50% of the slaves taken across the Atlantic, these studies reveal alot about the population effects of the trade whose overall effect was limited. These studies also show that the high population densities of the coast may have been a result of the slave trade rather than despite it, as slaves from the interior were incorporated within coastal societies like Angola, they also call into question the population estimates which are premised on the depopulation of Africa as a result of the slave trade (eg Patrick manning's estimated 30% decline in the population of central Africa between 1700-1850). The skewed gender ratio in the Angolan colony with more women than men, seems to support the arguments advanced recently by scholars such as Wyatt MacGaffey and Ivor Wilks who suggest that matrilineal descent among the costal groups of the Congo basin and among the Akan of the “gold coast” was a product of the Atlantic trade as these societies retained more female slaves54, although its unclear if all matrilineages pre-dated or post-dated the external slave trade.

Effects of Atlantic slave trade on the African economy:

The Atlantic slave trade is an important topic in African economic history and its effects are often seen as significant in measuring the level of africa’s pre-colonial economic development. Scholars argue that the depopulation of the continent which drained it of labor that could have been better applied domestically, and the dumping of manufactured goods which were exchanged for slaves, destroyed local handicraft industries in Africa such as textiles forcing them to depend on foreign imports. (giving rise to the so-called dependency theory)

For example, Paul Lovejoy combines his political and economic observation of the effects of external slave trade on Africa, writing that “the continent delivered its people to the plantations and mines of the Americas and to the harems and armies of North Africa and Arabia”, which resulted in a "period of African dependency" in which African societies were ruled by "warlords" who were "successful in their perpetuation of rivalries that effectively placed Africa in a state of retarded economic and political development". He argues that external slave trade transformed the African society from one initially where "slaves emerged almost as incidental products of the interaction between groups of kin" to one where "merchants organized the collection of slaves, funneling slaves to the export market” such that "the net effect was the loss of these slaves to Africa and the substitution of imported commodities for humans". He claims that this led to the development of a "slave mode of production" in Africa, where slaves were central to economic production across all states along the Atlantic (such as Kongo and Dahomey).55

Joseph Inikori on the other hand, looks at the effects of foreign imports on African industries. After analyzing the discussions of other scholars who argue for the limited effects of Africa's importation of European/Indian textiles (which were mostly exchanged for slaves), he argues that their claims are difficult to prove since they didn’t conduct empirical studies on pre-colonial west African manufacturing, he therefore proposes a study of pre-colonial west African industry based on import data of textiles from the records of European traders. He argues that west Africa had become a major export market for English and east India cottons, which he says replaced local cotton cloths in places like the "gold coast" (Asante/ modern Ghana) in the 17th and 18th century. He adds that "there is no indication at all that local cotton textile producers presented any competition in the West African market", continuing that these imports adversely affected production in previous supplying centers in Benin and Allada, which he says were edged out based on their “underdeveloped technology” of manufacture relative to the european producers.56

Lovejoy’s and Inikori’s observations depart from observations made by David Eltis. Basing on the revenue yields from slave trade per-population in Western Europe, the American colonies and West Africa, at the peak of the slave trade in the 1780s, Eltis calculates that Atlantic slave revenues accounted for between 5-8% of west African incomes. (his west African population estimate was 25 million, but a much higher estimate such as Manning's 32 million would give an even lower share of income from slavery) he therefore concludes that "It would seem that even more than most European nations at this time, Africans could feed, clothe and house themselves as well as perform the saving and investment that such activities required without having recourse to goods and markets from other countries".57

John Thornton on the other hand, in looking at the political and economic history of Atlantic Africa, argues that the Atlantic imports weren’t motivated by the filling of basic needs, nor was Africa’s propensity to import European (and Indian) manufactures, a measure of their needs, nor can it serve as evidence for the inefficiency of their industries. He argues instead, that the imports were a measure of the extent of their domestic market and a desire for variety, he calculates that imports such as iron constituted less than 10-15% of coastal west African domestic needs, excluding military needs which would push the figure much lower (he based this on a population estimate of 1.5 million for the coast alone, which would would make the share of iron imports much lower if measured against the entire west African population) He also calculates that the “gold coast” textile imports of 20,000 meters constituted barely 2% of the 750,000 meters required for domestic demand; a figure which doesn’t including elite consumption and the high demand for textiles in the region as a secondary currency.58

In a more detailed study of west-central African cloth production, Thornton uses Angolan colonial data from the early 17th century in which Luanda-based merchants bought over 100,000 meters of cloth from the eastern provinces of the Kongo kingdom each year after 1611 (a figure which doesn’t include illegal trade that didn't pass customs houses and weren’t documented), he thus estimates that total production from eastern kongo to have been around 300,000-400,000 meters of cloth for both domestic demand and exports. This production figure, coming for a region of less than 3.5 people per square kilometer, implies that eastern Kongo was just as (if not more) productive than major European manufacturing regions such as Leiden (in the Netherlands), in making equally high quality cloth that was worn by elites and commoners in west central Africa, this Kongo cloth also wasn't replaced by European/Indian imports despite their increased importation in Kongo at the time. He thus argues against the "use of the existence of technology (or its lack) as a proxy measure for productivity", adding that the rural-based subsistence labor of the eastern Kongo, working with simple ground and vertical looms, could meet domestic demand just as well as early industrial workers in the 17th century Netherlands, adding that early european textile machinery at the time was unlike modern 20th century machinery, and often produced less-than-desirable cloth, often forcing producers to use the ‘putting-out’ system that relied on home-based, less mechanized handworkers who produced most of the textiles.59

In her study of cloth manufacture and trade in East Africa and West Africa, Katharine Frederick shows that textile imports across the continent didn’t displace local industries but often stimulated local production. Building on Anthony Hopkin's conclusions that textile imports didn’t oust domestic industries, Katharine shows that the coastal African regions with the highest levels of production were also the biggest importers of cloth, and that African cloth producers in these regions, ultimately proved to be the most resilient against the manufactured cloth imports of the early 20th century. In comparing West Africa’s long history of cloth production against eastern Africa’s more recent history of cloth production, and both region’s level of importation of European/Indian cloth, she observes that "West Africa not only produced more cloth than East Africa but also imported more cloth per capita" .

She therefore points out that other factors account for the differences in Africa's textile industries, which she lists as; the level of population, the antiquity of cloth production, the level of state centralization and the robustness of trade networks, and argues that these explain why African weavers in high-import/ high-production regions along west africa’s coast, in the Horn of africa and the Swahili coast at Zanzibar, were also more likely to use more advanced technologies in cloth production with a wide variety of looms, and were also more likely to import yarn to increase local production, and foreign cloth as a result of higher purchasing power, compared to other regions such as the east African interior.60

Charts showing the imports of european/indian cloth in west africa and east africa, with an overall higher trend in the former than the latter, as well as higher imports for coastal societies in zanzibar than in mozambique.61

Map showing the varieties of textile looms used in Africa, showing the highest variety in the “slave coast” region of southern Nigeria.62

The above studies by Thornton and Katharine are especially pertinent in assessing the effects of external slave trade on African industries as the countries along the west-African and West-central coast exported 10 times as many slaves into the Atlantic (around 9 million) than countries along the east-African coast exported into the Indian ocean (around 0.9 million)63, and which in both regions were exchanged for a corresponding amount of European/Indian textiles (among other goods).

Furthermore, comprehensive studies by several scholars on Atlantic Africa's transition into "legitimate commerce" after the ban of slave exportation in the early 19th century, may provide evidence against the significance of the Atlantic slave export markets on domestic African economies. This is because such a transition would be expected to be devastating to their economies which were assumed to be dependent on exporting slaves in exchange for foreign imports.

In his study of the Asante economy in the 18th and 19th century, Dalrymple-Smith shows that the rapid decline of Asante’s slave exports shouldn’t solely be attributed to British patrol efforts at the coastal forts, nor on the seas, both of which he argues were very weak and often quite easily evaded by other African slave exporters and European buyers. He argues that the decline in slave exports from the “gold coast” region, should instead be largely attributed to the Asante state's withdraw from the slave export market despite the foregone revenues it would have received had it remained a major exporter like some of its peers. He shows that slave export industry was an aberration in the long-standing Asante commodity exports of Gold dust and kola, and thus concludes that the Asante state "did not lose out financially by the ending of the transatlantic slave trade"64

These conclusions are supported by earlier studies on the era of “legitimate commerce” by Elisee Soumonni and Gareth Austin, who studied the economies of Dahomey and Asante. Both of these scholars argue that the transition from slave exports to palm oil exports was a "relatively smooth processes" and that both states were successful in "accommodating to the changing commercial environment".65

Chart showing the hypothetical value of gold and slave exports had the Asante remained a major exporter (last bar) vs the true value of their Gold and Kola nut exports, without slave exports (first three bars).66

These studies on the era of legitimate commerce are especially important given that at the height of the trade in the 18th century, Asante and Dahomey either controlled and/or directly contributed a significant share of the slaves exported from the west African coast. Approximately 582,000 slaves leaving the port of Ouidah between 1727–186367, this port was by then controlled by Dahomey although over 62% of the slaves came from private merchants who travelled through Dahomey rather than from the state’s own war captives68. Approximately 1,000,000 slaves passed through the “gold coast” ports of Anomabu, Cape-coast-castle and Elmina in the years between 1650-1839.69 while most would have come from the Fante states at the coast,70 some doubtlessly came from the Asante.

That these exports fell to nearly zero by the mid 19th century without triggering a "crisis of adaptation" in the Asante and Dahomey economies, nor resulting in significant political ramifications, may support the argument that Atlantic trade was of only marginal significance for West African societies.

Sources of controversy: Tracing the beginnings of the debate on the effects of Atlantic trade on Africa.

The origin of the controversies underlying studies on Atlantic slavery from Africa lie not within the continent itself but ideological debates from western Europe and its American colonies, the latter of which were involved in the importation of the slaves and were places where slave labor played a much more significant role in the local economy (especially in the Caribbean), as well as in the region's political history (eg in the American civil war and the Haitian revolution), In a situation which was radically different on the African side of the Atlantic where political and economic currents were largely disconnected from the export trade. It's from the western debates between Abolitionists vs the Pro-slavery writers that these debates emanate.

Added to this were the ideological philosophies that created the robust form of social discrimination (in which enslaved people were permanently confined to the bottom of the social hierarchy primarily based on their race), that prompted historiographers of the slave trade to attempt to ascribe “blame”, however inaccurately or anachronistically, by attempting to determine which party (between the suppliers, merchants, and plantation owners) was ultimately guilty of what was increasingly being considered an inhumane form of commerce.

The intertwining of Africa’s political and economy history with abolitionist debates begun in the 18th century with British writers’ accounts on the kingdom of Dahomey, most of which were made by slave traders from the Pro-slavery camp of the Abolishionist debate. But neither the pro-slaver writers (eg William Snelgrave) nor the abolitionists (eg Frederick Forbes) were concerned with examining the Dahomean past but only haphazardly collected accounts that supported their preconceived opinions about "the relationship between the slave trade and the transforming Dahomean political apparatus."71

They therefore interpreted events in Dahomey's political history through the lens of external slave trade, attributing the successes/failures of kings, their military strategies, their religious festivals, and the entire social structure of Dahomey, based on the number of slaves exiting from Ouidah and how much British audiences of the abolitionist debate would receive their arguments72.

This form of polemic literature, written by foreign observers armed with different conceptual frameworks for cognizing social processes separate from what they obtained among the African subjects of investigation, was repeated in other African states like the Asante kingdom and ultimately influenced the writings of 19th century European philosophers such as Friedrich Hegel, who based his entire study of African history and Africans largely on the pro-slavery accounts of Dahomey written by the pro-slavery writer William Snelgrave73.

Beginning in the 20th century, the debates of African historiography were largely focused on countering eurocentric claims about Africa as a land with no history, scholars of African history thus discredited the inaccurate Hegelian theories of Africa, with their rigorously researched studies that more accurately reconstructed the history of African states as societies with full political and economic autonomy. But the debates on the Africa's contribution to the Atlantic trade re-emerged in the mid 20th century within the context of the civil rights movement in the US and the anti-colonial movement in Africa and the Caribbean, leading to the popularity of the dependency theory; in which African societies were beholden to the whims of the presumably more commercially advanced and militarily powerful European traders who interfered in local politics and dictated economic processes in the African interior as they saw fit.74

External slave trade was once again given an elevated position in Atlantic-African history. But faced with a paucity of internal documentation at the time, scholars engaged in a sort of academic “reverse engineering” of African history by using information from the logbooks of slave ships to reconstruct the political and social life of the interior. Atlantic slave trade was therefore said to have depopulated the continent, degraded its political institutions, destroyed its local industries, and radically altered its social structures and economies. External documentation about African states made by European slave traders and explorers, was often uncritically reproduced and accepted, while internal records and accounts of African societies were largely disregarded.

Fortunately however, the increased interest in Africa's political and economic history has resulted in the proliferation of research that reveals the robustness of pre-colonial African states and economies throughout the period of the Atlantic trade, added to this are the recently uncovered internal African documents especially in west Africa and west central Africa (from regions that also include Atlantic African countries such as Senegal75, the ivory coast, Ghana, Nigeria76 and Angola77), and which contain useful accounts of the region's political history ultimately proving that the continent's destiny before the colonial era, wasn't in control of external actors but was in the hands of the African states and societies which dominated the continent.

Conclusion: the view of the Atlantic world from Africa

The Atlantic slave trade was a dark chapter in African history, just as it was in the Americas colonies where the enslaved people were taken and forced to labor to produce the commodities which fueled the engines of the west’s economic growth, all while the slaves and their descendants were permanently excluded from partaking in the economic and the political growth of the states in which they resided. The intellectual basis of this exclusion was constructed in racial terms which rationalized the institution of chattel slavery, a brutal form of forced labor which the settlers of the colonies considered morally objectionable for themselves but morally permissible for the Africans,78 by claiming that both the slave suppliers in Africa and the slaves on American plantations, were incapable of “placing value on human life”, and in so doing, managed to simultaneously justify the brutal use of slaves as chattel (whose high mortality thus required more imports to replace them), and also justified the slave descendants’ permanent social exclusion based on race.

The history of internal African slavery on the other hand, is a lengthy topic (that i hope to cover later), but it shows that the above western rationales were far from the reality of African perceptions of slavery as well as its institution in the various states within the continent. As i mentioned above, African states had laws which not only protected their citizens including going as far as repatriating them from slave plantations in the American colonies, but also laws determining who was legally enslavable, who would be retained locally, who was to be exported. African written documents also include laws regarding how slaves were to be treated, how long they were allowed to work, how much they earned, and how they earned/were granted freedom. Unlike the static political landscape of the colonies, Africa’s political landscape was fluid, making slavery a rather impermanent social status as slaves (especially those in the army) could overthrow their masters and establish their own states, (several examples include Sumanguru of Soso, Mansa Sakura of Mali empire, Askiya Muhammad of Songhai empire, Ngolo Diarra of Bambara empire), slave officials also occupied all levels of government in several African states and wielded power over free subjects especially in the Songhai and Sokoto empires where virtually all offices from finance to the military were occupied by slave officials), slaves could be literate, could accumulate wealth and own property. In summary, Slavery in Africa wasn’t dissimilar from ‘old world’ slavery in medieval Europe, Asia and the Islamic world and was quite unlike the extreme form of chattel slavery in the Atlantic. Just like their ignorance of African political and economic systems, western writers’ understanding of African social institutions including slavery, was equally inaccurate.

The ideas of “guilt” and “blame” in the context of Africa’s role in the Atlantic reveals statements of value rather than fact, and the ludicrous notion of “Africans enslaving Africans” is an anachronistic paradigm that emerged from the western rationale for racial-chattel slavery and modern concepts of “African-ess” and “Blackn-ess” which were unknown in pre-colonial African states, the latter instead defined their worldview in political, ethnic and religious terms. A free citizen in Kongo for example identified themselves as part of the “Mwisikongo” and not as an “African brother” of another citizen from a totally different kingdom like Ndongo. This is also reflected in accounts of redeemed slaves themselves, as hardly any of their testimonies indicate that they felt betrayed by “their own” people, but rather by foreign enemies, whom they often described by their political/ethnic/religious difference from themselves.79

This post isn’t an attempt to “absolve” Euro-American slave societies from their own legacies of slavery (which they continue to perpetuated through the descendants of slaves down to the modern day), nor to shift “guilt” to the African suppliers, but its a call for scholars to study each society within its own context without overstating the influence of one region over the other. Its also not aimed at exposing a rift between scholars of African history, as most of the scholars mentioned above are excellent educators with decades of research in their respective field, and the vast majority of their work overlaps with that of the other scholars despite their disagreements on a few issues: there doesn’t need to be a consensus among these scholars for us to extract an accurate understanding of African history from their research.

The Atlantic trade, remains an important chapter in African history, it is however, one among many chapters of the continent’s past.

If like this article, or would like to contribute to my African history website project; please donate to my paypal

Down all books about Atalntic slave trade from Africa (listed in the references below), and read more about African history on my Patreon account

The Struggle against the Transatlantic Slave Trade: The Role of the State by Joseph E. Inikori pg 170-196)

Transformations in slavery by Paul Lovejoy pg 122-123)

The Atlantic Slave Trade from West Central Africa, 1780–1867 by Daniel B. Domingues da Silva pg 3-5)

The Atlantic Slave Trade from West Central Africa, 1780–1867 by Daniel B. Domingues da Silva pg 73-88)

The Atlantic Slave Trade from West Central Africa, 1780–1867 by Daniel B. Domingues da Silva pg 84

The kongo kingdom by Koen Bostoen, Inge Brinkman, pg 36- 41, the elusive archaeology of kongo’s urbanism by B Clist, pg 377-378, The elusive archeology of kongo urbanism by B Clist, pg 371-372, A History of West Central Africa to 1850 by J. K. Thornton, pg 34)

The Kingdom of Kongo. by Anne Hilton, pg 34-35)

this introduction is an abridged version of my article on Kongo history

Slavery and Its Transformation in the Kingdom of Kongo by LM Heywood pg 3-4, The Volume of the Early Atlantic Slave Trade, 1450-1521 by Ivana Elbl pg 43-42, History of West Central Africa to 1850 by J. K. Thornton pg 52-55

History of West Central Africa to 1850 by J. K. Thornton, pg 6-9, 72)

Slavery and Its Transformation in the Kingdom of Kongo by LM Heywood pg 5-6

History of West Central Africa to 1850 by J. K. Thornton 5-6)

Precolonial african industry by john thornton pg 12-14)

History of West Central Africa to 1850 by J. K. Thornton pg 94-97)

(Slavery and its transformation in the kingdom of kongo by L.M.Heywood, pg 7, A reinterpretation of the kongo-potuguese war of 1622 according to new documentary evidence by J.K.Thornton, pg 241-243)

Atlas of the Transatlantic Slave Trade by David Eltis pg 137-138)

Atlas of the Transatlantic Slave Trade by David Eltis pg 87-90)

Transformations in slavery by Paul Lovejoy pg 40,53)

History of West Central Africa to 1850 by J. K. Thornton pg 72

A History of West Central Africa to 1850 by J. K. Thornton, pg 149-150, 160, 164)

A History of West Central Africa to 1850 by J. K. Thornton, pg 176, Kongo origins dynamics pg 121-122

A History of West Central Africa to 1850 by J. K. Thornton, pg 244-246, 280-284)

The Atlantic Slave Trade from West Central Africa, 1780–1867 by Daniel B. Domingues da Silva pg 92)

Map Courtesy of Henry B. Lovejoy, African Diaspora Maps Ltd

these books describe the internal systems of the Asante, while they don’t specifically discuss how they related to the external slave trade, they nevertheless reveal its rather marginal place in Asante Politics; “State and Society in Pre-colonial Asante” by De T. C. McCaskie and “Asante in the Nineteenth Century” By Ivor Wilks

Commercial Transitions and Abolition in West Africa 1630–1860 pg 167-173)

Commercial Transitions and Abolition in West Africa 1630–1860 pg 168

The slave coast of west africa by Robin Law pg 267-280

The Precolonial State in West Africa by Cameron Monroe pg 62-68

Wives of the leopard by Edna G. Bay pg 30)

Fighting the Slave Trade: West African Strategies by Sylviane A. Diouf pg 187

The Precolonial State in West Africa by Cameron Monroe pg 74-76

The slave coast of west africa by Robin Law pg 300-308

Slave Traders by Invitation by Finn Fuglestad pg 97),

Ouidah The Social History of a West African Slaving 'port' 1727-1892 by Robin Law pg 117-118, 121-124)

Dahomey in the World: Dahomean Rulers and European Demands, 1726–1894 by John hornton, pg 450-456

Slavery and African Life by Patrick Manning 85)

“African Population, 1650 – 1950: Methods for New Estimates” by Patrick manning, and, “African Population, 1650–2000: Comparisons and Implications of New Estimates” by Patrick Manning

“World Economy: A Millennial Perspective” by Angus Maddison and “Historical Population Estimates” by John Caldwell and homas Schindlmayr

The long term effects of Africa’s slave trades by Nathan Nunn pg 139-176)

African Population, 1650–2000: Comparisons and Implications of New Estimates by Patrick Manning pg 37

African Population, 1650 – 1950: Methods for New Estimates by Region by Patrick Manning 7

We Do Not Know the Population of Every Country in the World for the past Two Thousand Years by Timothy W. Guinnane pg 11-13)

The slave coast of west africa by robin law pg 222)

Demography and History in the Kingdom of Kongo, 1550–1750 by John Thornton pg 417-427

Demography and History in the Kingdom of Kongo, 1550–1750 by John Thornton pg 521-526

african fiscal systems as sources of demographic history by thornton and heywood 213-228

african fiscal systems as sources of demographic history by thornton and heywood 221 ,224,225

The Slave Trade in Eighteenth Century Angola: Effects on Demographic Structures by John Thornton pg 417- 427

The Atlantic Slave Trade from West Central Africa, 1780–1867 pg 95

The Slave Trade in Eighteenth Century Angola: Effects on Demographic Structures by John Thornton pg 421

The Atlantic Slave Trade from West Central Africa, 1780–1867 pg 92-93

The Atlantic Slave Trade from West Central Africa, 1780–1867 pg 98)

The Kongo Kingdom: The Origins, Dynamics and Cosmopolitan Culture of an African Polity by Koen Bostoen, Inge Brinkman pg 49-52

Transformations in slavery by Paul Lovejoy pg 68, 44-45 10, 121-122)

English versus Indian Cotton Textiles by Joseph Inikori pg 85-114)

Economic Growth and the Ending of the Transatlantic Slave Trade. By David Eltis pg 71-73)

Africa and Africans in the Making of the Atlantic World, 1400-1800 by John Thornton pg 47-52)

Precolonial African Industry and the Atlantic Trade, 1500-1800 by J Thornton · pg 1-19)

Drivers of Divergence: Textile Manufacturing in East and West Africa from the Early Modern Period to the Post-Colonial Era by Katharine Frederick pg 205-233

Twilight of an Industry in East Africa: Textile Manufacturing, 1830-1940 by Katharine Frederick pg 206, 227

Twilight of an Industry in East Africa: Textile Manufacturing, 1830-1940 by Katharine Frederick pg 212

These calculations are based on Nunn’s country-level estimates of slave exports in “The long term effects of Africa’s slave trades” by Nathan Nunn pg 152)

"Commercial Transitions and Abolition in West Africa 1630–1860" By Angus E. Dalrymple-Smith pg 155-161

From slave trade to legitimate commerce by Robin Law pg 20-21)

Commercial Transitions and Abolition in West Africa 1630–1860" By Angus E. Dalrymple-Smith pg 155

Atlas of the Transatlantic Slave Trade by David Eltis pg 122)

Ouidah: The Social History of a West African Slaving 'port' 1727-1892 by Robin Law pg 112

Atlas of the Transatlantic Slave Trade by David Eltis 116, 118,123)

The Fante and the Transatlantic Slave Trade by Rebecca Shumway pg 8

The Precolonial State in West Africa by Cameron Monroe pg 15-16,

Wives of the leopard by Edna G. Bay pg 29-31)

The Horror of Hybridity by George Boulukos, in “Slavery and the Cultures of Abolition” pg 103

Labour and Living Standards in Pre-Colonial West Africa by Klas Rönnbäck pg 2-6

Arquivos dos Dembos: Ndembu Archives

Philosophers on Race: Critical Essays by Julie K. Ward, Tommy L. Lott pg 150-152

Fighting the Slave Trade: West African Strategies by Sylviane A. Diouf pg xiv

Good