WHEN AFRICANS WROTE THEIR OWN HISTORY; A CATALOGUE OF AFRICAN HISTORIOGRAPHY WRITTEN BY AFRICAN SCRIBES FROM ANTIQUITY UNTIL THE EVE OF COLONIALSIM

Far from being a continent without history, Africa is simply a continent whose written history has not been studied

Much Ink has been spilled on mundane debates on whether or not Africa had written history and many times, Africanists have labored time and again to explain to their non-African (often western peers) just how robust the literary cultures of Africa were contrary to academia's and the general public's undaunted belief in the "oral continent per excellence"[i] this distracting lockstep has unfortunately drowned out the rigorous work needed to translate, analyze, interpret and utilize these precious documents of the African past

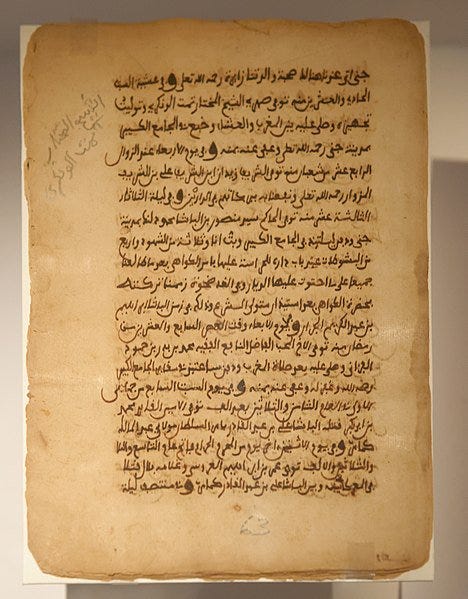

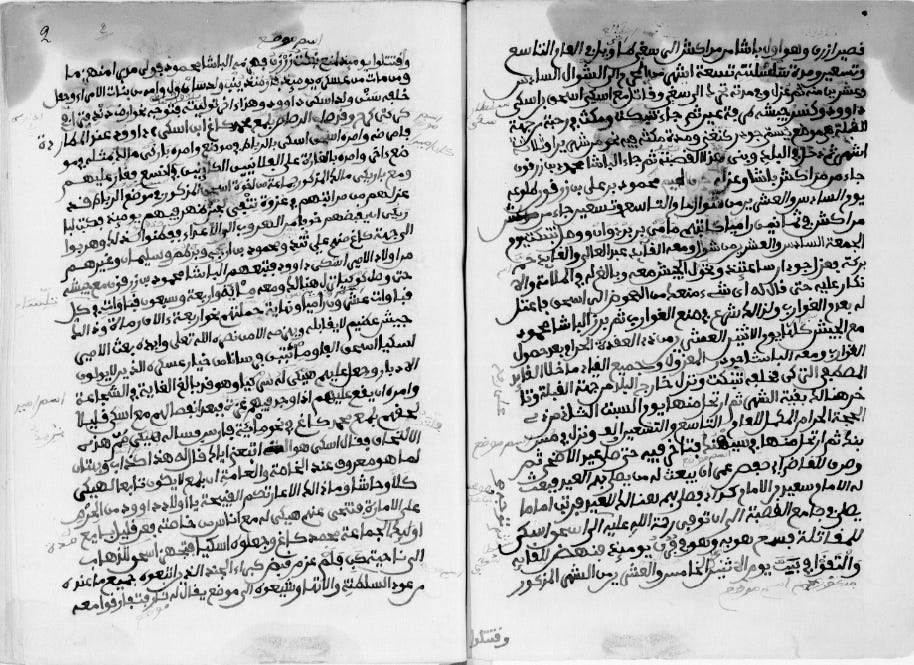

In this post, rather than sink in the murk of the debate on African literacy, I'll instead try to catalogue -as best as I can- the most readily available, digitized or photographed documents of Africa history written by African scribes from antiquity until the eve of colonialism, also provided will be images of the documents and direct links for digitized copies of the manuscripts.

Since the bulk of African scribal production was not about historiography (which is simply; written narratives of history) these documents constitute a very tiny fraction of African literary works, but even this tiny fraction is so large that writing about it would probably require several books so I’ll try to condense this catalogue as concisely as I can.

Support African History Extra by becoming a member of our Patreon community, subscribe here to read more on African history and keep this blog free for all:

HISTORIOGRAPHICAL DOCUMENTS FROM THE KINGDOM OF KUSH (Sudan)

The majority of Kush’s historiography is contained in its royal chronicles; these inscriptions recorded royal actions such as military campaigns, legal decrees and temple and building donations and constructions all of which are dated anddetailed[ii]

The texts were mostly conceived in an “indigenous Kushite intellectual milieu”[iii] to formulate Kushite concepts, record events in Kush and regulate affairs according to Kush’s law and tradition but initially using a foreign language and script –Egyptian hieroglyphics during the Napatan era (from 800-300BC when the capital of 25th dynasty Egypt and Kush was at Napata in Sudan). The Kushites would later invent Meroitic script to write their documents in their own language – Meroitic during the period when their capital was at Meroe in central Sudan

For Kush’s documents inscribed in Egyptian hieroglyphics, the first of such is a monumental sandstone stela called the “Great Triumphal Stela of king Piye” made in 727BC, it recounts the exploits of the Kushite king Piye who became the first Egyptian pharaoh of the 25th dynasty.

It’s the longest royal inscription in Egyptian hieroglyphs”[iv]

The "Dream Stela" of Kushite king Tanwetamani”

Inscribed by a scribe from Napata in 664BC, the stela narrates Tanwetamani's "restoration of the double kingdom of Kush and Egypt from the condition of chaos" after he defeated the Assyrian puppet Necho I plus the delta & sais chiefs and briefly restored the “double kingdom” of Kush and Egypt to its original extent[v]

King Aspelta’s stele, of which, at least three are available online

As narrated in the three documents, Aspelta’s reign was overshadowed by internal controversy, an unheard of crime occurred in the Amun temple at Napata as described in the banishment stela most likely involving the Amun priests conspiring to elect another ruler appointed by a false oracle a capital offence for which all involved were executed by the king, and at unknown later date, his name, the face of the Queen Mother, her cartouches, and the cartouches of Aspelta's female ancestors were all erased from the election stela indicating his legitimacy and that of his female succession line were rejected[vi]

Aspelta Election’s election/coronation Stela, inscribed in the late 7th century BC, at the Nubian museum in aswan

Apelta’s banishment stela inscribed in the late 7th century BC

Aspelta’s adoption stela inscribed in the late 7th century BC

king Nastasen’s stela from the late 4th century BC describing his enthronement and various military expeditions to secure the territories of Napatan kingdom by sending military campaigns in lower Nubia, against the southern cattle nomads around Meroe, against the medja (ancestors of modern Beja nomads)

(SMB’s URL’s aren’t permanent, so you can use this google search link instead, it displays this one result at all times)

Aryamani’s donation Stela from the first 1st half of the 3rd century BC

By this time, the Meroitic language of the scribes was beginning to have an impact on the transcription of the Egyptian hieroglyphs although not much can be read off this fragmentary stela[vii]

Historiographical documents inscribed in the Meroitic script

While Meroitic, a north eastern Nilo-Saharan language, was the native language of the Kushites (that is; the kingdom’s rulers, elite, and majority of its people) since the time of the kingdom of Kerma in the 3rd millennium BC[viii], it was only rendered into written form after the emergence of a new dynasty in Kush during the 3rd century BC that originated from the more southerly Butana region in central Sudan, deposing the old Napatan dynasty (that had ruled Egypt as the 25th dynasty)[ix]

The Meroitic language itself remains deciphered but Meroitic inscriptions in hieroglyphic and cursive can be read by comparing royal names recorded In both Egyptian and Meroitic scripts[x]

King Tanyidamani’s dedication tablet with Meroitic inscriptions from the late 2nd century BC

While mostly un-deciphered, this stela indicates the continuity in the kingship dogma of the cults of Amun of Napata and Thebes[xi]

Queen Amanirenas’ triumphal inscriptionsfrom the late 1st century BC detailing her military campaigns against roman Egypt

The two stela while also un-deciphered, most likely narrate the war between Kush and Rome fought between 25-24BC this war ended in a stalemate and a peace treaty that was likely perceived as a victory to Kush [xii]

HISTORIOGRAPHICAL DOCUMENTS FROM THE KINGDOM OF AKSUM (Northern Ethiopia and Eritrea)

On writing in Aksum

Written inscriptions first appeared in the northern horn of Africa (modern regions of northern Ethiopia and Eritrea) during the 9th century BC in the form of two scripts; the Sabean script and proto-Ge’ez (old Ethiopic) the latter of which became the Ge’ez script that becomes the dominant script of the northern horn until the early modern era[xiii]

A few of these inscriptions attest to a polity that archeologists have named D’mt but unfortunately, these inscriptions weren’t long enough to reveal the political history of the enigmatic polity itself beyond the names of its rulers

By the early 1st millennium sections of the population in the emerging state of Aksum were literate in both Ge’ez (Ge’ez was the dominant language of Aksum but also the name of the Ethiopic script) and Greek and they rendered inscriptions of both scripts on stone, paper, parchment and coinage

It’s during this era that we get more detailed accounts of the region’s history.

Historiographical documents from Aksum

The first of such is King Ousana’s inscription on his invasion of Kush

These two fragmentary stele are perhaps the earliest record of African warfare between the two largest sub-Saharan African states of antiquity, the Greek inscriptions “RIE 286” and “6164” now kept in the Sudan national museum as “SNM 508” and “SNM 24841” preserve the title of the ruler inscribed on them reading; “King of the Aksumites and Ḥimyarites” and narrates his capture and sack of several Kushite settlements, capture of members of Kush’s royal families, subjection of Kush to tributary status, setting up an Aksumite throne of Ares at Meroe and the erection of a Bronze statue[xiv] although these victories were likely ephemeral

(for Image for “SNM 508” see 図 2 in <pdf> )

and for “SNM 24841” see “Fig. 1” in <pdf>

King Ezana’s stele

At least 11 of the 15 royal inscriptions at the city of Aksum alone were made by this king, most are inscribed in the scripts of; Ge’ez, Greek and ancient south-arabian (which is why are often referred to as trilingual inscriptions but are actually bilingual, being written in just two languages; Ge’ez and Greek)

While all inscriptions are well preserved and available in various locations in the city of Aksum, the few that are often posted online are inscriptions “RIE 185” and RIE 271” housed in a small building at Aksum. Both inscriptions narrates Aksum’s various wars of expansion under Ezana

With “RIE 185” recording campaigns against the Beja nomads north west of Aksum[xv] and RIE 271 recording a second Aksumites war in Kush fought on 4th march 360AD[xvi], but this time, against the Noba (the people of the later kingdom of Noubadia) who were by then the overlords of what was now a rump state of Kush

Most photos of these Ezana stone inscriptions are of RIE 271 eg this one

Perhaps one of the most significant yet understudied pieces of Aksumite historical literature was a recently discovered manuscript now referred to as the “Aksumite collection”[xvii] its a Ge’ez codex dating back to the mid5thcentury to the early 6th century and its mostly concerned with ecclesiastical history of the early church including; texts on the councils of Constantinople and Chalcedon, an Ethiopic version of the lost Greek Apostolic Tradition and the History of the Alexandrian Episcopate

This manuscript is one of the oldest from Ethiopia (alongside the Garima gospels) and has since been partially digitized (although access is restricted) at this website

Other minor written historical information from Aksum can be derived are the inscriptions on aksumite coins which preserve the names of at least 20 kings providing a chronology of Aksumite kingship from the 3rd century to the 7th century plus depictions of their royal regalia[xviii]

Many of these coins are currently in several western institutions and photos of them are available online eg at this gold coin issued by king Ezana in the mid-4th century

This gold coin was issued by king Kaleb in the 6th century; king Kaleb conquered much of western Yemen and some of his coins have been found there

And this copper-alloy coin from the 7th century issued by king Armah better known as the famous King Najashi in Islamic tradition

HISTORIOGRAPHICAL DOCUMENTS FROM THE KINGDOMS OF CHRISTIAN NUBIA (Noubadia, Makuria, Alodia)

On writing in Christian Nubia

The fall of Kush in 360 AD to Aksumite incursions, Nubian expansion[xix] and Blemmye nomads led to the gradual disappearance of documents in the Meroitic script.

Initially, the “Meroitic-ized” elites of the successor chiefdoms ruled by the abovementioned Nubians and the Blemmyes continued using Meroitic script; as best attested by the Meroitic inscription of King Kharamadoye of the Blemmye found on the façade of the Hypostyle of the Mandulis temple at Kalabsha, that recording his military campaigns dated to between 410-440AD

But with Increased cultural contacts between Rome and these successor chiefdoms also led them to adopt Greek, as such, several Blemmye kings left Greek inscriptions in the abovementioned Kalabasha temple, the Blemmyes were later expelled from lower Nubia (the region currently under lake Nasser) by the Noubades (Nubians) led by king Silko who left a lengthy Greek inscription in the kalabsha temple recounting his campaigns to expel the Blemmyes in 450AD [xx]

By the early 6th century, three large Nubian kingdoms arose; Noubadia, Makuria and Alodia which were then converted to Christianity in the mid-6th century and, with increasing cultural interactions with Coptic Christians from Egypt, adopted the Coptic script and soon invented the Old Nubian script in the 8th century.

On Christian Nubia’s historiography

Although the vast majority of the more than 6,000 documents[xxi] discovered from these three kingdoms mostly epitaphs, land sales and other legal documents (half of which have been catalogued sofar at this database of medieval Nubian texts, a few inscriptions are of historiographical nature particularly the foundation stones of Nubian cathedrals, some wall inscriptions/graffitto and royal letters

Majority of these documents are in situ and unexcavated but some of the foundation stones are currently housed in the Sudan national museum and the Warsaw museum in Poland and only few of the letters can be located

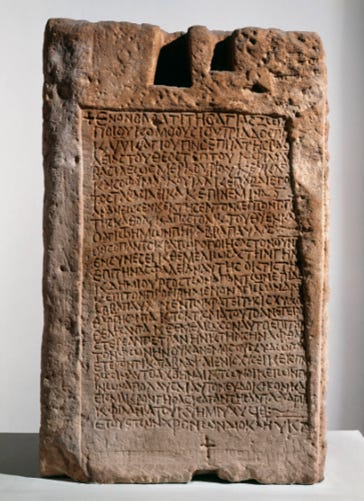

The foundation stones include, The Faras foundation stone inscribed in Greek commemorating the reconstruction and restoration of the cathedral of Mary at Faras details given include the name of the Makurian king Mercurios, the date of commencement of construction in 707AD, 11th year of the king’s reign, the name of the cathedral’s bishop a Paulos

A foundation inscription of Iesou, eparch of Noubadia made on 23rd April 930 that provides the dating of King Zacharias’s reign as in the 15th year among others.

“fig. 4” in <pdf>

Other minor historiographical information can be derived from the dozens of Nubian land sales documents (espcially from qasr ibrim), in the graffito on the churches at Old Dongola and Banganarti, on murals and other paintings and the rest can also be found in the inscriptions from Faras at the Warsaw museum

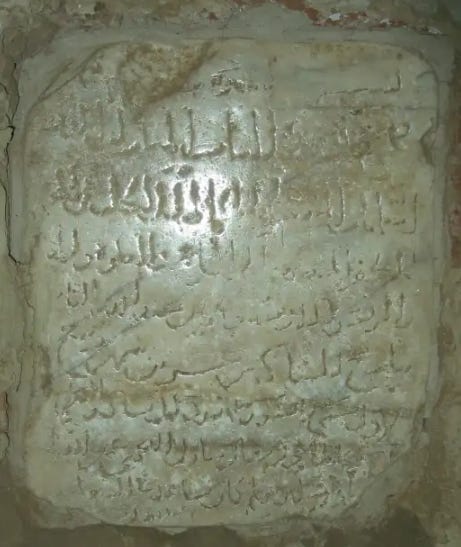

The kingdom of Makuria went into decline after the 12th century which saw the decline of its literary culture with increasing succession wars and Mamluk Egypt aggression, one feature of this period was the conversion of some of the Christian elites to Islam and the introduction and use of the Arabic script most notably, the conversion of the Dongola throne hall into a mosque commemorated on a foundation stone inscribed by the newly converted king Seif-el-Din Abdullahi el Nasir in 1317AD;

HISTORIOGRAPHICAL DOCUMENTS FROM THE HORN OF AFRICA

Historiographical documents from the “Christian” horn of Africa (northern Ethiopia and Eritrea)

After a period of decline following the fall of Aksum, The northern horn's literary culture underwent a resurgence beginning in the 12th century during the era of the Zagwe kings but especially after the 14th century following the so-called solomonic "restoration" when a dynasty of amhara origins deposed the Zagwe dynasty and claimed decent from the old Aksumite kings

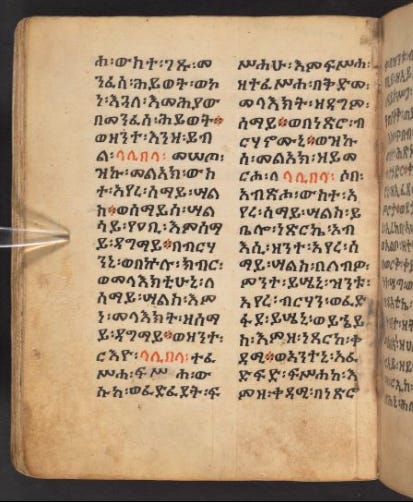

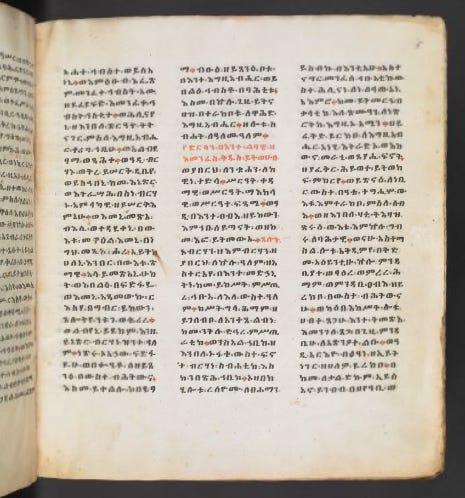

A particular feature of this resurgence was the extensive use of written history to legitimize royal and ecclesiastical authority in the form of royal chronicles and hagiographies; the royal chronicles deal with specific years of a king's reign and there are at least 20 such chronicles from the 14th to the 20th century for the majority of Ethiopian emperors[xxii] while the hagiographies deal with the lives of saints; these are Ethiopian missionaries that are associated with the expansion and consolidation of the Ethiopian orthodox church and there are several dozen of such hagiographies

The chronicles provide important primary sources for the political history of medieval Ethiopia while the hagiographies provide its social history and have since been used extensively in reconstructing Ethiopia’s past and the also, wider the history of the horn of Africa.

Majority of the royal chronicles are however kept in several Ethiopian institutions, monasteries and private collections and have yet to be digitized[xxiii] but fortunately, several translations of them exist and have since been used to reconstruct the Ethiopian past, on the other hand, some hagiographies are fairly common and have thus been digitized and entire copies of them are available online especially at the British library endangered archives program

I have arranged them by century

15th century texts

Kebrä nägäst (The Glory of Kings), this is a copy of the famous 14th century foundational epic written to prop up the “Solomonic dynasty” that ruled Ethiopia after the 13th century until the 20th century becoming the authority of the Ethiopian monarch and continuously used as such recently as Ethiopia’s 1955 constitution. Parts of it may have been written in the 6th century during the Aksumite era

The Acts of Lālibalā; one of the oldest digitised royal chronicle, it was written by Abba Amha in 1434AD it was written about the acts of king lalibela know for the famous rock-hewn churches of lalibela [xxiv]

The Acts of Gabra Manfas Kedus; a hagiography about the life and works of Ethiopian saint Manfas Kedus

The acts of Adlä äbunä Samuel emennä Wäldebba– about the Life of Saint Samuel from Wäldebba, composed between 1460-1499AD

17th century texts

Donations of king 'IyasuII.,Berhan Sagad (A.D. 1730-55), and his mother Walatta Giyorgis, Berhan Mdgasa, to the church of Kweskwam, at Dabra Zahai near Gondar

Kebra Negast; a 17th century copy of the famous text

Gädlä Anorewos – an important manuscript on the Life of the 14th century monk and saint Anorewos that was written in the 17th century. It includes historical information on emperor Amda seyon’s reign (1314-1344)[xxv]

Manuscript on the Genealogy of Ethiopian Kings through King Iyasu II (1755)

18th century

Born in 1215AD, he was Perharps the most famous of the Ethiopian church saints, he was instrumental in the spread of Christianity during the early period of the solomonic empire and was a powerbroker between the church and the royalty [xxvi] there are atleast five hagiographies currently at the british library

similar hagiographies of the saint include this, this , this, and this

Life and Miracles of Saint Gabra Manfas kedus; a hagiography on the life of the saint Gabra Manfas Qəddus, and this

The Acts of Walatta Petros; a hagiography on Ethiopia’s most famous female saint, she was born in 1592 and was partly responsible for the resilience of the Ethiopian orthodox church against the attempts by the Jesuit missions to make catholism the state religion during the mid-17th century reign of Susenyos who had converted to catholism leading to a brief civil war[xxvii]

Illustrated copy here

Aragāwi Manfasawi. A work on Ethiopia’s ecclesiastical history

Maṣḥafa Manakosāt. (The Book of the Monks) an important collection of Ethiopian monastism

The Life of Atnātewos. A hagiography of atnatewos

Kebra Negast, "the Glory of the Kings”.

The Acts of Fāsiladas, a chronicle on the emperor Fasilidas one of the most famous of the Gondarine rulers especially for his castle of Fasil Ghebbi that stands in the city of Gondar.

Chronicle of the Kings of Ethiopia.

Compendium of History; Chronicles of Ethiopia.

This contains copies of the original 14th century chronicle of Emperor Amda Tsion - "the glorious victories" that was written in 1332 recounting his conquest of and expansion into various states in eastern and central Ethiopia[xxviii]

19th century

Gädlä Lalibla ("The Acts of Lalibela) or History of King Lalibala of Lasta, a copy of the abovementioned 15th century chronicle on the famous zagwe king Lalibela, containing illustrations of him building his famed rock-hewn churches

History of Iyasu Adyam Säggäd a chronicle of the gondrine emperor Iyasu I (1682-1706)

A history of Ethiopia gathered from different sources. By Ethiopian Orthodox Church.

The History and Culture of the Šanqǝla People. By Tämäsgen Gäläta. On the history of the people in the modern region of Benishangul-Gumuz in ethiopia probably composed in the early 20th century

HISTORIOGRAPHICAL DOCUMENTS FROM THE “MUSLIM HORN OF AFRICA” (eastern Ethiopia and Somalia)

On writing in the Muslim horn of Africa

Writing in the Muslim horn of Africa begun as early as the late 1st millennium to the 13th century as attested to by the Arabic inscriptions in several mosques and on tombstones from Dahlak to the Somali cities of Mogadishu to Ethiopian cities like Awfat and Haarla (figures 22 and 23 ) , recording of the Historiography of the region begun in the mid second millennium with the influx of schools and visiting scholars in the urban settlements particularly Harar which was at several points a capital of successive Muslim kingdoms like Adal and the Harar sultanate all of which interacted extensively with Christian Ethiopia in warfare, diplomacy and trade

Majority of this region’s historiographical works are now in Ethiopian institutions and haven't been digitized and even fewer of them have been studied eg Abdallah sarif's private collection in Harar and others at the Berlin state library seem to have been moved

However, some are available online eg;

Historiographical documents from the Muslim horn of Africa

Titled; ‘Hikaya fi qissat tarikh Umar Walasma wa-ansabihi wa muddat wilayatihi’ its a

Genealogy of the Walasma rulers of the kingdom of ifat[xxix] and was probably written in the late 16th century in relation to several other chronicles of the era

An anonymously written chronicle on the History of Zara Yaqob and Nur Ibn Mujahid; a history of the horn from the 15th century reign of the Ethiopian king Zara Yacob upto Ibn Mujahid, the 16th century sultan of harar[xxx]

This is an Amharic translation of the original Arabic work, both composed before the 19th century

Records of the Qāḍī court at Harar from the late 19th century

HISTORIGRAPHICAL DOCUMENTS FROM WEST AFRICA(Senegal, Mali, Niger, Nigeria, Ghana, Ivory Coast, Burkina Faso, Guinea)

On writing in West Africa

West Africa’s literary culture begins in the early years of the 11th century[xxxi] with increasing cosmopolitanism of the early West African empires and kingdoms particularly between the Ghana Empire, Kanem Empire and Gao kingdom; with the Maghreb (morocco, Mamluk Egypt) and the wider Islamic world (ottomans)

the earliest extant writing was found in the regions of eastern and central Mali in the cities of Essuk, Gao, Saney and Bentiya/Kukyia which were all associated with the earliest west African states of Gao and Ghana, this writing was in the form of over a hundred epitaphs inscribed in the Arabic script but for deceased local rulers and Muslims who had Songhay, Mande and Berber names dating from the 11th to the 15th century[xxxii]

while there’s evidence of writing and scholarship in the empires of Ghana and Kanem during the 12th century (such as the 12th century Kanuri poet al-Kanemi, the invention of Kanem’s unique Barnāwī script in the 12th century[xxxiii] and the presence of Ghana’s scholars in Andalusia in the 1100s) the perishability of paper in west Africa’s climate makes it unlikely for any manuscripts from such early dates to be discovered –indeed the oldest west African manuscript is a letter by Mai Uthman Idris of Kanem written in 1391 AD to the Ottoman sultan al Zahir Bakuk[xxxiv]

as for the epitaphs, historical information contained on these includes names of rulers of the Gao kingdom’s Za dynasty eg the epitaph of king Muhammad b. Abdallah b. Zâghï who died in 1100 [xxxv] , the epitaph of two royal women, one bearing the title malika (possibly of a queen with full authority) named M.S.R who died in 1119AD and a princess Bariqa who died in 1140AD

Historiographical documents from West Africa;

The Royal chronicles and general histories;

The Bornu chronicles on the kingdom of Bornu (western Chad and northern Nigeria)

the oldest extant manuscripts on west African historiography were produced in the mid-16th century starting with Kanuri scholar Ibn Furtu’s[xxxvi] chronicles of the Kanem-Bornu sultan Mai Idris Alooma, the first of these was Ghazawāt Barnū (The Book of the Bornu Wars) written in 1576AD, the second was Ghazawāt kānem (The Book of the Kanem Wars)

Written not long after was the anonymously authored Diwan salatin al Barnu[xxxvii] (Annals of the kings of Bornu) which was essentially a Kanem-Bornu king list, copies of all three are currently available at the SOAS

The Tarikh genre of the “western sudan”

TheTaʾrīkh Al-Sūdān (chronicle of the Sudan) written by Al-Saʿdi' in Timbuktu in 1655AD which was the first among the so-called Tarikh genre of chronicles, these described the political and social history of western Sudan (a region covering much of west Africa) from the rise of the Ghana empire through the ascendance of Mali and Songhai to the fall of the latter in the late 16th century, various copies of it are kept in several institutions both African and western

The Tārīkh al-Fattāsh (or more accurately; the Tārīkh Ibn al-Mukhtar) initially written by the scribe Ibn al-Mukhtar in 1664 but later heavily edited and transformed by the Massina propagandist Nuh Al-Tahir in the early 1840s who used it to legitimatize Ahmad lobbo as the 12th caliph [xxxviii] copies of it are available in several collections eg this one at the mamma haidara library

the anonymously authored chronicle on the history of the Timbuktu pashalik from 1591 to 1737AD titled Taḏkirat al-nisyān fī aḫbār mulūk al-Sūdān[xxxix]

and another is history of Timbuktu from 1747 to 1815 writen by mulay sulayman [xl]

The history of west africa, east africa and west-central africa continues in the next post …

How about from Cameroon and Kingdom of Kongo?

Very late. But where can I find info about scholars from the Ghana Empire in Al Andalus?