WHEN AFRICANS WROTE THEIR OWN HISTORY (PART 2)

Far from being a continent without history, Africa is simply a continent whose written history has not been studied

continued from the previous post …

The “greater voltaic region” chronicles

A number of chronicles from the “greater voltaic region” covering much of modern Ghana, Burkina Faso and Ivory Coast written by the Wangara/Soninke immigrants in the kingdoms of Gonja, Dagomba, Wa, etc

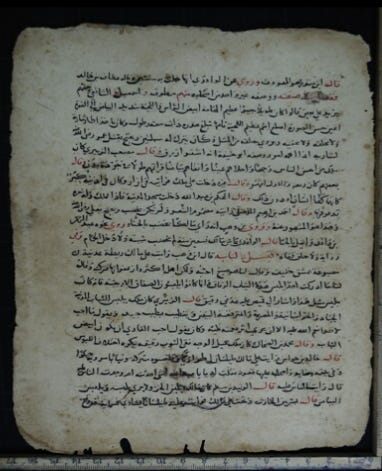

The vast majority of these chronicles are very detailed and are stylistically similar to the abovementioned “Tarikh genre” such as the Kitab Ghanja written by Muhammad al-mustafa in 1764 is a detailed account of the history of the Gonja kingdom and the Asante invasion, these are housed in the university of ghana’s Institute of African Studies at legon and are unfortunately not digitized and only a few photocopies from this vast collection can be found online such as Imam Imoru’s hausa poem on the coming of Europeans[xli] (titled “ajami manuscript in hausa” )

Other chronicles of the “western Sudan” region

Kitaabou fi zikri taradjoumi Asmaa-i ridjaali written in the 18th century

and Kitatou kitaabi fi taariki

Chronicles from the Senegambia region;

A Chronicle on the Berekoloŋ Warlikely written in the 19th century

The manuscript deals with the war between the pre-colonial kingdoms of Kaabu and Fuuta Jalon called Berekoloŋ Keloo in Mandinka. The manuscript goes back to the time when the Fulani of Fuuta Jalon invaded and occupied Mandinka lands of Kaabu and the key leaders who fought in the war

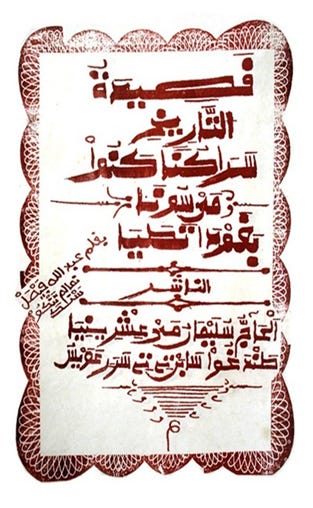

on the life of Khali Madiakhate Kala. (1835-1902) A 19th-Century Wolof Scholar

an Arabic poem titled dealing with important historical events and figures in the 19th century in Senegambia. It tells the story of Khali Madiakhate Kala who was one of the leading Wolof scholars, and his relationship with Lat Dior Ngone Latyr Diop, the last Wolof king who took arms against French colonization.[xlii]

"An extract of history of the western Sudan entitled Zuhur al basa-fie ta-rikh al Sudanby Sheikh Musa Kamra of Matan, Segal muqaddam written between 1279-1281 A.H/1862-1864 A.D

Tarikh As sudani, a copy on the history of the “western sudan” that was influenced by the abovementioned tarikh al-sudan, many copies of the latter were circulating in the Senegambia region eg this section of the Tarikh Al sudan is marked as “Or 6473, f 266r” in the britsh library

Historiographical Documents from the central Sudan region (northern Nigeria, southern Chad and eastern Niger)

On the history of the Soninke people (Wangara/dyuula traders) in the “central sudan”;

The Asl al-Wanqariyin (Wangara chronicle) written in 1650AD[xliii] by an anonymous Soninke author, about the migration of Zaghayti; a Wangara/dyula teacher and his clan from the mali empire to kano and their settlement there. A copy of its folio of it is available at the link provided above

On the history of sokoto and the hausalands;

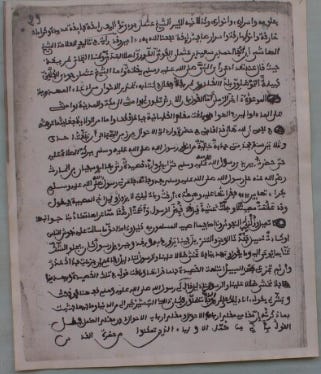

TheTa'rikh Sokoto (the sokoto chronicles) written by al-Hājj Sa'id in 1854AD

a history of the sokoto empire till the author’s time in 1854[xliv]

Tarikh al-Musamma (kano chronicle) written by the scribe Dan Rimi Malam Barka in 1880.

it’s a detailed account on the history of the hausa city-state of kano from the 10th to the late 19th century[xlv] the anonymously authored Wakar Bagauda (Song of Bagauda) may also be attributed to the same scribe

Rawdat al-afkar (The Sweet Meadows of Contemplation) written in 1824 by Abd Al-Qadir Al-Mustafa Al-Turudi (Dan Tafa) a west african philosopher and polymath who wrote on a wide range of topics from philosophy to geography to history to the sciences[xlvi]

original manuscript and its translation in this pdf

he also wrote on History of the hausa people

A list of Several works on history written by the Fodiyawa clan; (this was the family of Uthman Dan Fodio the Sokoto empire founder)

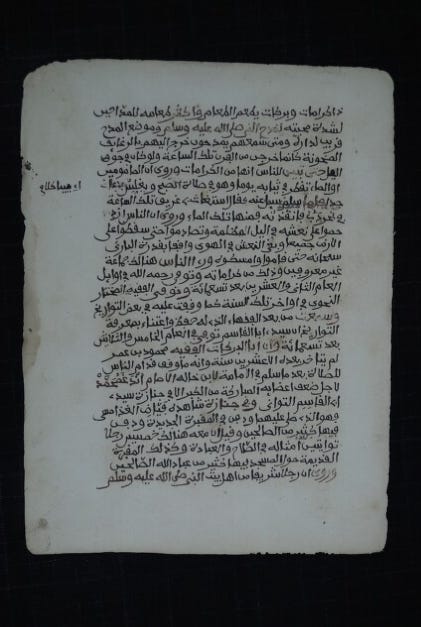

Tanbih al fahim ; on the brief history of the world and other eschatological themes[xlvii] written by sheikh Uthman Fodio (1754-1817), the founder of the Sokoto caliphate

Kitab al Nasab[xlviii] a book on the origins of the Fulani people, written by Abdullahi bin Fodio (1874-1829)

Qasidat la-mi-yah; about the wars at Katami; Argungu and Kwalambaina written by Sultan Bello

Fa'inna ma'al Asur yasuran[xlix] ; written in 1822AD by Nana Asmau (perhaps the most prominent female scholar in 19th century west Africa) it was about the conflict between Sokoto, Gobir and the Tuareg

Works written on important people in Sokoto such as;

"The Meadows of Paradise"[l], a book recalling the miracles/good deeds of Sheikh Uthman dan Fodio. It was written by the chief minister of Sokoto under sultan Bello, Gidado dan Layma. It was compiled sometime after the death of Usman in 1817.

There are several chronicles written in the first decades of the 20th century which I will try to summarize such as the history of katsina[li] ;

others are on the history of kano and on the history of damagaram

HISTORIOGRAPHY OF EAST AFRICA (Kenya and Tanzania)

On writing along the east African coast (the Swahili coast)

The oldest extant writing along the Swahili coast begins in the 1106AD with the Arabic inscription on Zanzibar’s kizimikazi mosque[lii], the Swahili are an eastern bantu-speaking group that settled along the east african coast during the mid-1st millennium and gradually, their fishing villages grew into mercantile cities by the early second millennium flourishing as “middlemen” in the lucrative trade in gold from Great Zimbabwe that they traded with southern Arabia[liii], it was with this increased cosmopolitanism that the Swahili cities adopted the Arabic script and begun a vibrant literary culture, of which, inscriptions on epitaphs, walls and coinage survive from the classical era (1000-1500AD) and written manuscripts survive from the later era (1500-1900AD)

Of the few Swahili manuscripts that have been studied, the oldest surviving are disputed, with ‘Swifa ya Mwana Manga’ from 1517AD, the Hamziya from 1652AD and the Goa archive’s Swahili letters from 1711 all being possible candidates

The fact that manuscripts only survive at the later era is likely because of the tropical climate and probable Portuguese destruction

The vast majority of epitaphs, wall inscriptions, graffito and coinage is in situ and has barely been documented so virtually none have been digitized[liv], fortunately, some partial catalogues such as coins with inscriptions, inscribed blocks and cast plasters of inscribed tombstones from the cities of Kilwa and Kunduchi held in a number of western institutions but catalogued by the British Institute in Eastern Africa Image Archive , inscribed on these are names of Swahili royals and elites such as;

A Commemorative inscription for the construction of the Husuni Kubwa palace built by sultan sulayman[lv] in the city of Kilwa in Tanzania

A Copper alloy coin of sultan Sulayman from 1302AD

An Epitaph of Sayyida Aisha Bint Ali dated 1359AD[lvi]; one of several from kilwa's classical era

A tombstone of sultan Shaf la-Hajji dated 1670AD with the name of his father named as Mwinyi Mtumaini"[lvii] which is one of the earliest unambiguously Swahili names recorded on the coast (the shomvi were a prominent swahili clan associated with the cities of kunduchi, kaole and bagamoyo)[lviii]

On Swahili historiography

While some of the Swahili manuscripts have been digitized, especially the Utendi poems and Swahili Korans from the 17th-19th centuries eg here , none of the Swahili’s better known documents of historiography have been digitized

For example, the oldest extant document of Swahili historiography is the kilwa chronicle; its titled Kitab al-Sulwa ft akhbar Kilwa and was written in 1530AD but its two original chronicles and a 19th cent. copy remain undisguised, the latter of which is at the British library listed as "Or. 2666"[lix]

Of historiographical importance are the 18th century Kilwa letters written in Arabic by the rulers of Kilwa and addressed to Mwinyi Juma a swahili spy in Mombasa working for the Portuguese and currently housed in the Goa archives of which some were digitized by the SOAS London eg the letters from queen regent Fatima Binti Sultan Mfalme Muhammad[lx]

Her daughter Mwana Nakisa, and Fatima's brothers Muhammad Yusuf and Ibrahim Yusuf[lxi]

other un-digitised chronicles include the mid-19th century pate chronicle[lxii] and the more recent ‘kitab al zanuj’ and ‘Kawkab al-. Durriya li-akhbar Ifriqiya’ written in the late 19th and early 20th century[lxiii]

HISTORIOGRAPHICAL DOCUMENTS FROM WEST CENTRAL AFRICA (Angola and the DRC)

Writing in the kingdom of kongo

While evidence of writing in "pre-Atlantic" Kongo (prior to Portuguese contact) is minimal, the beginning of Kongo’s literary tradition during the early years of king Joao Nzinga's interactions with Portuguese missionaries in the 1490s is undisputed, the kingdom quickly adopted the Latin script for writing both Kikongo and Portuguese documents, and a vibrant book culture soon developed.

literacy rapidly proliferated throughout the kingdom's provinces with the establishment of schools[lxiv] after which letter-writing became a powerful political instrument especially between the Manikongo (King of Kongo) and Kongo’s titleholders, and between the titleholders themselves, this begun in king Afonso's reign in the early 16th century and continued well into the 19th century long after the kingdom's decline[lxv] letter writing also became a diplomatic tool with dozens of letters addressed to Kongo’s allies; Portugal, the Dutch and Rome

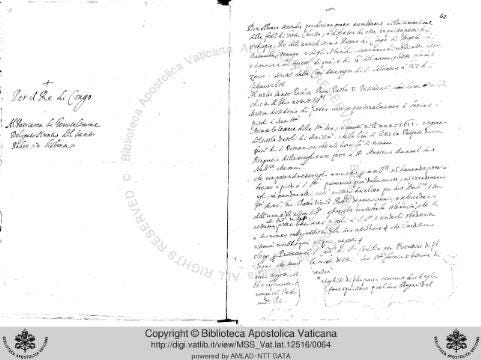

Unfortunately few internal manuscripts from Kongo survive in Angola and DRC both due to the vagaries of tropical climate on the durability of paper and the ruinous civil wars of Kongo in the 17th and 19th century but fortunately, many of those letters and documents addressed to Kongo’s foreign allies survive and some have been digitized such as the Kongo manuscripts collection at the 'Torre do Tombo National Archive' and the Kongo manuscript collection at the 'Vatican archives' under the shelf mark Vat.lat.12516

From the former archive, we have mostly correspondence between the Kongo kings and the Portuguese kings on political and ecclesiastical matters eg;

A Letter from king Afonso asking king John iii of Portugal to allow a certain Mwisi-kongo noble into Paris for the latter's studies

A Letter from Antonio Vieira (a powerful Mwisi-kongo nobleman) that is addressed to king Henry of Portugal reporting on copper in Kongo written in 1566AD

And several dozens of letters from the 16th to the 17th century from various kings on various issues that can be visited here

Historiographical documents from the kingdom of kongo

There exists a Kongo chronicle written by Antonio da Silva; duke of the Kongo province of Mbamba that was addressed to bishop Manuel Baptista in 1617 titled "Reis christaos do Congo ate D. Alvaro iii" (translated; Christian Kings of Congo up to D. Alvaro III) a short version of the original chronicle was reproduced by Manuel Baptista and is currently in the archives of Evora while i couldn't locate the actual manuscript (probably because its un-digitised), it was published in Brasio's “African Missionary Monument. Volume 6" on page 296 (free pdf )

The chronicle lists Kongo's kings from King Afonso I in 1509 to the chronicler’s own time during Alvaro III's reign in 1617 including brief notes on each king's reign such as the death of king Bernado I in 1567 while fighting the Jagas (a rebel group of Yaka people along kongo's eastern borders)

Perhaps the most useful historiographical information can be retrieved from the abovementioned Vatican archives eg

King Alvaro ii's letter to Pope Paul V written on 27th February 1613 stating Alvaro II’s accusations against the Portuguese in Kongo and the bishop of Sao Salvador[lxvi] (scroll to 64, 65, the folios are numbered 62 and 63 )

Another is King Alvalro iii’s letter to Pope Paul V written 25th July 1617on his succession to the throne after the death of King Bernado II and the disputes that arose with Antonio da Silva; the abovementioned duke of Mbamba

And the rebels that allied with the Jagas against the king[lxvii] (scroll to 69, the folio is numbered “66” )

Letter from King Alvaro iii to Pope Paul V, written on 23rd may 1619 asking him to name Bras Correia as bishop; this priest had since become a political mediator between the various Mwisi-kongo titleholders and Kongo’s electors and would later play an important role in aversion of civil war after Alvaro iii's death, the letter also details the internal political situations in Kongo in which the Antonio Da Silva, the abovementioned duke of Mbamba, was involved[lxviii]

(scroll to "73" the folio is numbered "70" )

There are dozens of Kongo’s manuscripts in the Vatican archive 12516 that I haven’t listed but are published in Brasio's book (that I linked above) and go into more detail on Kongo’s history and other matters such as finances, politics and the Kongolese church and have since been used in reconstructing Kongo’s history[lxix]

ON THE USE OF THE ARABIC SCRIPT IN AFRICAN HISTORIOGRAPHY

Majority of the African historiographical documents compiled before 1900AD were written in the Arabic script, save for the Ethiopian and Kushite-Nubian literary cultures that had the advantage of antiquity to develop indigenous scripts early enough.

The adoption of this foreign script by African societies was simply a matter of time and convince, majority of early African states' growth coincided with the rise of the early Islamic empires in the second half of the 1st millennium, the latter of which were by then the center of gravity of the afro-Eurasian old-world civilization; a vast, cosmopolitan society stretching from Spain to the islands of Indonesia, that was loosely bound by trade, religion (Islam) and a lingua-franca (Arabic), the benefits of integrating within this culture -if only through the use of its script- outweighed the costs of inventing and propagating an indigenous script (although many African societies invented several scripts during this period) besides, few ancient societies invented scripts independently and the vast majority of scripts in the world are derived from perhaps less than half a dozen “parent scripts”

Plus, these African societies faced few handicaps in using the Arabic script because they "indigenized" it into the Ajami script (a form of Arabic script for writing non-Arabic languages) and innovated various ways of writing it such as the abovementioned Barnāwī script and the various "Sūdānī scripts" used in west Africa allowing them to preserve an "unadulterated" African viewpoint that presents an original African narration of its internal history that's free from the cultural biases found in most external sources.

CONCLUSION

To paraphrase Meikal Mumin’s quote; "Africa is not a continent without writing. Rather, it is a continent without studies on (its) writing" its clear that, far from being a continent without history, Africa is simply a continent whose written history has not been studied

African scholars wrote hundreds of documents narrating their own history, crafting an African centered discourse to explain historical phenomena and to legitimize authority by appealing to the written past

<most notably in legitimizing the “Solomonic restoration” in Ethiopia using the Kebre Negast and in legitimizing the “12th caliph” (Ahmad Lobbo) in Massina (modern Mali) using the Tarikh Al Fattash>

African historiography was actively produced, read and manipulated just like all written histories have but these processes have been largely ignored by both academia and in the mainstream discourses of history

As the philosopher Souleymane Bachir Diagne writes; “it is time to leave what we could call a griot paradigm that identifies Africa with Orality, in order to envisage a history of (written) erudition in Africa.”1

Support African History Extra by becoming a member of our Patreon community, subscribe here to read more about African history, download free books, and keep this newsletter free for all:

incase you prefer reading both these articles in pdf form; here’s a google drive link

References …

[i] Koen Bostoen, Inge Brinkman, The Kongo Kingdom pg 218

[ii] Torok Laszlo, the Kingdom of Kush pg 37

[iii] Torok, pg 57

[iv] Torok, pg 132

[v] Torok, Laszlo pg 185

[vi] Torok, pg367-369

[vii] Torok, pg 394

[viii] Rilly Claude, The Meroitic Language and Writing System pg 177

[ix] Torok pg 420-23, pg 443

[x] Torok, pg 62

[xi] Torok pg 47

[xii] Torok, pg 456

[xiii] Philipson David, Foundations of an African civilizations pgs33-40

[xiv] Hatke George, Aksum and Nubia warfare pg 67-80

[xv] Hatke, pg 105

[xvi] Hatke, pg 97

[xvii] Bausi Alessandro, Composite and Multiple-Text Manuscripts: The Ethiopian Evidence

[xviii] Philipson, pg 181-193

[xix] Torok Lazslo, Between two worlds pg 518

[xx] Torok Lazlo, Between two worlds pg 527

[xxi] Ochala Grzegorz, Multilingualism in Christian Nubia pg 3

[xxii] Pankhurst Richard, The Ethiopian royal chronicles

[xxiii] Tamrat Taddesse, Church and state in Ethiopia pg 4

[xxiv] Pankhurst Richard an introduction to the economic history of Ethiopia pg 62 [xxv] Tamrat Taddesse, pg 180-82

[xxvi] Tamrat Taddesse pgs 160-

[xxvii] Galawdewos, The Life and Struggles of Our Mother Walatta Petros

[xxviii] Ullendorff, Edward The Glorious Victories of 'Amda Ṣeyon, King of Ethiopia [xxix] John O Hunwick Vol3 Arabic Literature of Africa, Volume 3. The Writings of the Muslim Peoples of Northeastern Africa pg 35

[xxx] hunwick vol3 pg 37

[xxxi] Paulo F. de Moraes Farias, The Oldest extant writing of West Africa : Medieval epigraphs from Issuk, Saney and Egef-n-Tawaqqast (Mali)

[xxxii] Paulo F. de Moraes Farias, Bentyia (Kukyia): a Songhay–Mande meeting point, and a “missing link” in the archaeology of the West African diasporas of traders, warriors, praise-singers, and clerics

[xxxiii] Andrea Brigaglia Mauro Nobili, Central Sudanic Arabic Scripts (Part 2): The Barnawi

[xxxiv] John O. Hunwick, Rex Séan O'Fahey, Arabic Literature of Africa: The writings of central Sudanic Africa Vol.2 pg 16

[xxxv] Lange, Dierk. From Ghana and Mali to Songhay: The Mande Factor in Gao History ·

[xxxvi] Hunwick, Vol.2 pg 27

[xxxvii] Hunwick Vol2 pg 568

[xxxviii] Nobili, Mauro, Sultan, Caliph, and the Renewer of the Faith

[xxxix] Hunwick, John, Arabic literature of Africa: the writings of western Sudanic Africa Vol4 pg 41

[xl] Hunwick, vol4 pg 41

[xli] Hunwick Vol.2 pg 592

[xlii] Hunwick Vol4 pg 397-8

[xliii] Hunwick Vol2 pg 582

[xliv] Hunwick Vol 2 pg 233-234

[xlv] Lovejoy, Paul , The Kano Chronicle Revisited

[xlvi] Hunwick vol2 pg pgs 222-230

[xlvii] Hunwick vol2 pg 74

[xlviii] Hunwick Vol2 pg 97

[xlix] Hunwick Vol2 pg 165

[l] Hunwick Vol2 pg 187

[li] Hunwick Vol2 pg

[lii] G. S. P. Freeman-Grenville and B. G. Martin, A Preliminary Handlist of the Arabic Inscriptions of the Eastern African Coast pg1

[liii] Stephanie Wynne-Jones, Adria LaViolette, The Swahili world

[liv] Ridder H. Samsom swahili manuscripts: Looking in East African Collections for Swahili Manuscripts in Arabic Script

[lv] Freeman-Greenville, A preliminary handlist pg 29

[lvi] Freeman-Greenville, pg 30

[lvii] Freeman-Greenville, pg 28

[lviii] steven Fabian, making identity on the swahili coast

[lix] Adrien Delmas, “Writing in Africa” in The Arts and Crafts of Literacy: Islamic Manuscript Cultures in Sub-Saharan Africa

[lx] yayha ali omar, A 12/18th century Swahili letter from KiIwa Kisiwani being a study of one folio from the Goa Archives

[lxi] Edward A. Alpers, Ivory & Slaves in East Central Africa pgs pgs 72-74

[lxii] Randall L. Pouwel, The Pate Chronicles Revisited: Nineteenth-Century History and Historiography

[lxiii] James McL. Ritchie, Sigvard von Sicard, An Azanian Trio: Three East African Arabic Historical Documents

[lxiv] Koen Bostoen, Inge Brinkman, The Kongo Kingdom pg 218-225

[lxv] Anne Hilton, The Kingdom of Kongo pg 81-84

[lxvi] Antonio Brasio, Monumenta missionaria Africana Vol6 pg 128-132

[lxvii] Brasio, Vol.6 pg 288-290

[lxviii] Brasio, Vol.6 pgs 252-254

[lxix] John Thornton, The Correspondence of the Kongo Kings, 1614-35: Problems of Internal Written Evidence on a Central African Kingdom

Souleymane Bachir Diagne, The Ink of the Scholars: Reflections on Philosophy

in Africa

This is great. Well documented.The study is well focused. Thank you so much.

Just great stuff. What do you think about the information on this page www.whispersinear.com