a brief note on Trade and Travel in the ancient Sahara and beyond.

uncovering the origins of Carthage's aethiopian auxiliaries.

Covering nearly a third of the African continent, the Sahara Desert conjures visions of torrid heat waves rising over an endless sea of burning sand dunes where only the bravest nomads dared to tread.

Discourses on the Sahara throughout history have been dominated by the persistent belief that the desert was largely uninhabited and uninhabitable. Closely related to these discourses was the diffusionist hypothesis that African societies depended on exogenous contact in order to achieve social evolution.

Combining these two presumptions about the Sahara and African societies, early scholarship introduced the concept of a habitable 'corridor', that was understood to be a narrow stretch of land across the desert and the only route through which Mediterranean influences could reach "inner Africa".

It was in this context that Nubia was imagined to be a corridor through which technological and cultural innovations were "transmitted" from the Mediterranean world to Africa. The same concept of a corridor through the desert was applied to the Fezzan and Kawar oases of the central Sahara. All these corridors were thought of as routes through which everything from iron technology to statecraft were transmitted from Egypt and Carthage to the rest of Africa.

Ruins of Djado in the Kawar oasis of North-Eastern Niger. this medieval town is located at the very center of the Sahara.

As later research uncovered the ancient foundations of social complexity in Africa, the diffusionist paradigm was largely discarded by most scholars. The ancient furnaces of the Nok culture in central Nigeria had no connections to Carthage, nor were the forms of Nubian statecraft similar to Egypt. As one scholar summarized: "Surely corridors usually lead to a few rooms, but the Nubian corridor, in which so much happened, does not seem to have led anywhere."1

Yet the concept of a corridor cutting through the barren desert persisted, no longer as a conduit for transmitting "civilization" from North to south, the Saharan oases were now imagined to be highway stations along ancient routes which supposedly begun on the mediteranean coast and terminated in the old towns of west Africa and Sudan. Maps of medieval Africa are today populated with lines crisscrossing the desert, that are meant to represent fixed routes taken by carravans in the centuries past.

However, like its diffusionist precursor, this notion of oases as fixed highway stations along direct lines in the desert has not stood up to closer scrutiny. As one historian of the Sahara cautions; "It is thus hazardous and inexact to depict Saharan trails on maps as though they were established as major highways. The historical geography of Saharan trails is in fact very complicated, with numerous variants on routes followed depending on the shifting geopolitical realities as well as the natural limitations of travel across a hyper-arid zone."2

The world of the Sahara, map by D. J. Mattingly

Trans-Saharan travel and exchanges proceeded by regional stages, with the eventual long-distance transport being accomplished by numerous local exchanges. The societies and economies of Saharan communities were largely sustained by local resources and regional trade, rather than depending on tolls from long-distance trade. Such was the case for the Kawar Oasis towns, as well as the desert kingdom of Wadai, both of whose domestic economies did not significantly rely on long-distance trade with north-Africa, but from regional trade with neighboring states.

However, travel and trade did occur across the Sahara, often utilizing well-known itineraries through which goods and technologies were exchanged. How far back Trans-Saharan travel and exchanges begun is a matter of heated debate, with most scholars asserting that it started with the introduction of the camel at the start of the middle ages, while others claim that wheeled chariots were crossing the Sahara during the age of the Romans and the Carthaginians.

The ancient links between Carthage and West Africa is the subject of my latest Patreon article, in which I explore the evidence for ancient exchanges in the central Sahara, inorder to uncover the origins of the aethiopian auxiliaries of Carthage’s armies.

read more about it here:

Join the African history Patreon community and support this website

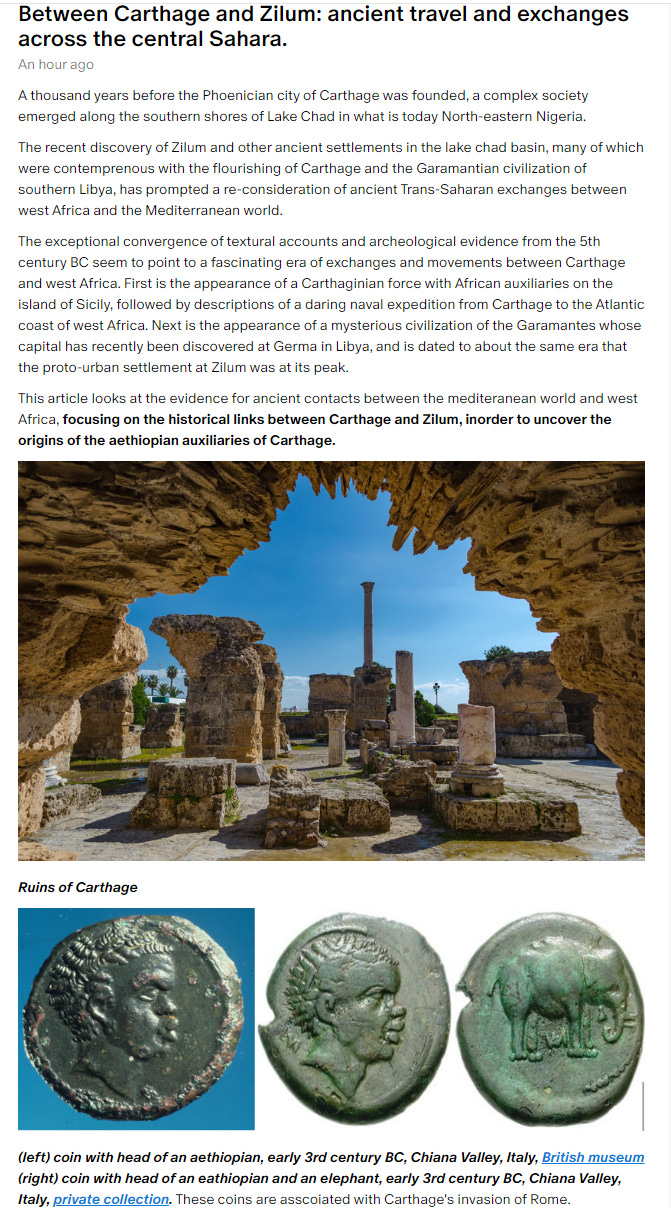

Ruins of Carthage in Tunisia.

African Civilizations: Precolonial Cities and States in Tropical Africa: An Archaeological Perspective by Graham Connah, pg 65

Trade in the Ancient Sahara and Beyond edited by D. J. Mattingly, pg 8

Carthage had black mercenaries/auxiliaries/soldiers? cool!