A complete history of Abomey: capital of Dahomey (ca. 1650-1894)

Journal of African cities chapter 10.

Abomey was one of the largest cities in the "forest region" of west-Africa; a broad belt of kingdoms extending from Ivory coast to southern Nigeria. Like many of the urban settlements in the region whose settlement was associated with royal power, the city of Abomey served as the capital of the kingdom of Dahomey.

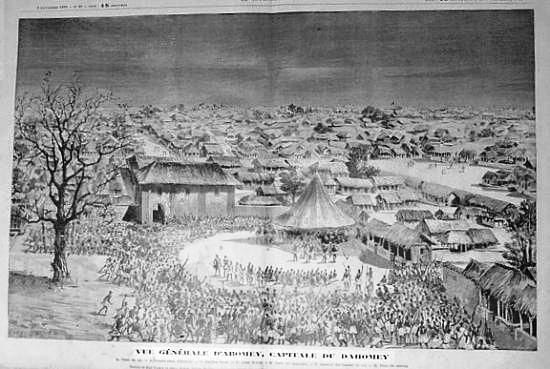

Home to an estimated 30,000 inhabitants at its height in the mid-19th century, the walled city of Abomey was the political and religious center of the kingdom. Inside its walls was a vast royal palace complex, dozens of temples and residential quarters occupied by specialist craftsmen who made the kingdom's iconic artworks.

This article outlines the history of Abomey from its founding in the 17th century to the fall of Dahomey in 1894.

Map of modern benin showing Abomey and other cities in the kingdom of Dahomey.1

Support African History Extra by becoming a member of our Patreon community, subscribe here to read more on African history and keep this blog free for all:

The early history of Abomey: from the ancient town of Sodohome to the founding of Dahomey’s capital.

The plateau region of southern Benin was home to a number of small-scale complex societies prior to the founding of Dahomey and its capital. Like in other parts of west-Africa, urbanism in this region was part of the diverse settlement patterns which predated the emergence of centralized states. The Abomey plateau was home to several nucleated iron-age settlements since the 1st millennium BC, many of which flourished during the early 2nd millennium. The largest of these early urban settlements was Sodohome, an ancient iron age dated to the 6th century BC which at its peak in the 11th century, housed an estimated 5,700 inhabitants. Sodohome was part of a regional cluster of towns in southern Benin that were centers of iron production and trade, making an estimated 20 tonnes of iron each year in the 15th/16th century.2

The early settlement at Abomey was likely established at the very founding of Dahomey and the construction of the first Kings' residences. Traditions recorded in the 18th century attribute the city's creation to the Dahomey founder chief Dakodonu (d. 1645) who reportedly captured the area that became the city of Abomey after defeating a local chieftain named Dan using a Kpatin tree. Other accounts attribute Abomey's founding to Houegbadja the "first" king of Dahomey (r. 1645-1685) who suceeded Dakodonu. Houegbadja's palace at Abomey, which is called Kpatissa, (under the kpatin tree), is the oldest surviving royal residence in the complex and was built following preexisting architectural styles.3

(read more about Dahomey’s history in my previous article on the kingdom)

The pre-existing royal residences of the rulers who preceeded Dahomey’s kings likely included a hounwa (entrance hall) and an ajalala (reception hall), flanked by an adoxo (tomb) of the deceased ruler. The palace of Dan (called Dan-Home) which his sucessor, King Houegbadja (or his son) took over, likely followed this basic architectural plan. Houegbadja was suceeded by Akaba (r. 1685-1708) who constructed his palace slightly outside what would later become the palace complex. In addition to the primary features, it included two large courtyards; the kpododji (initial courtyard), an ajalalahennu (inner/second courtyard), a djeho (soul-house) and a large two-story building built by Akaba's sucessor; Agaja.4

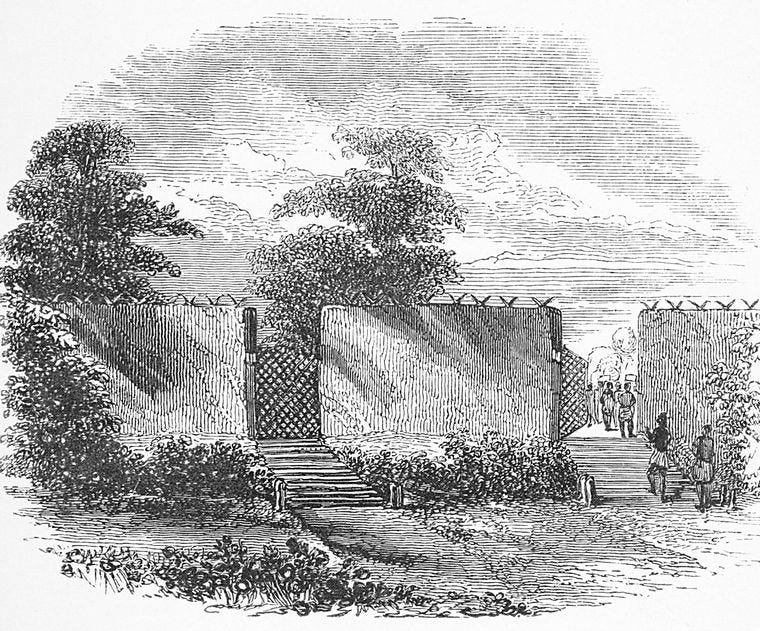

Agaja greatly expanded the kingdom's borders beyond the vicinity of the capital. After nearly a century of expansion and consolidation by his predecessors across the Abomey Plateau, Agaja's armies marched south and captured the kingdoms of Allada in 1724 and Hueda in 1727. In this complex series of interstate battles, Abomey was sacked by Oyo's armies in 1726, and Agaja begun a reconstruction program to restore the old palaces, formalize the city's layout (palaces, roads, public spaces, markets, quarters) and build a defensive system of walls and moats. The capital of Dahomey thus acquired its name of Agbomey (Abomey = inside the moat) during Agaja's reign.5

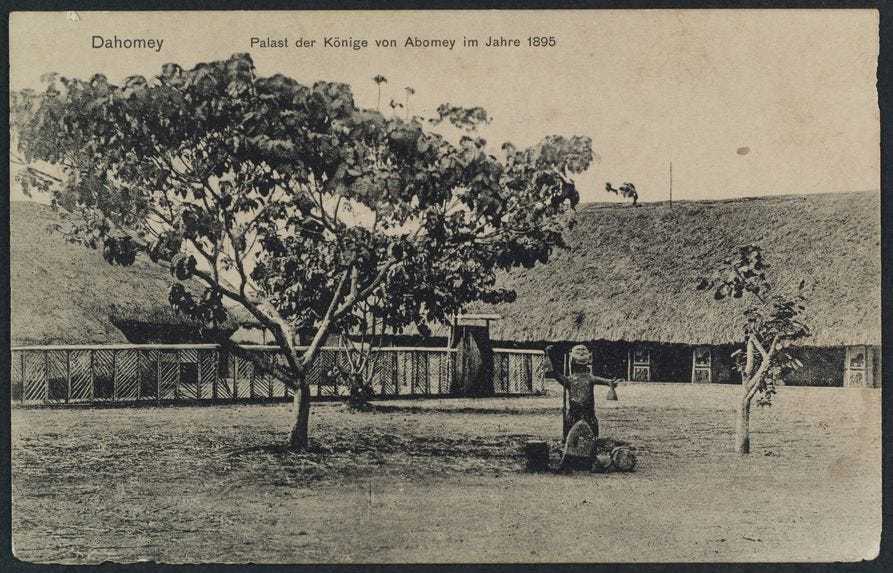

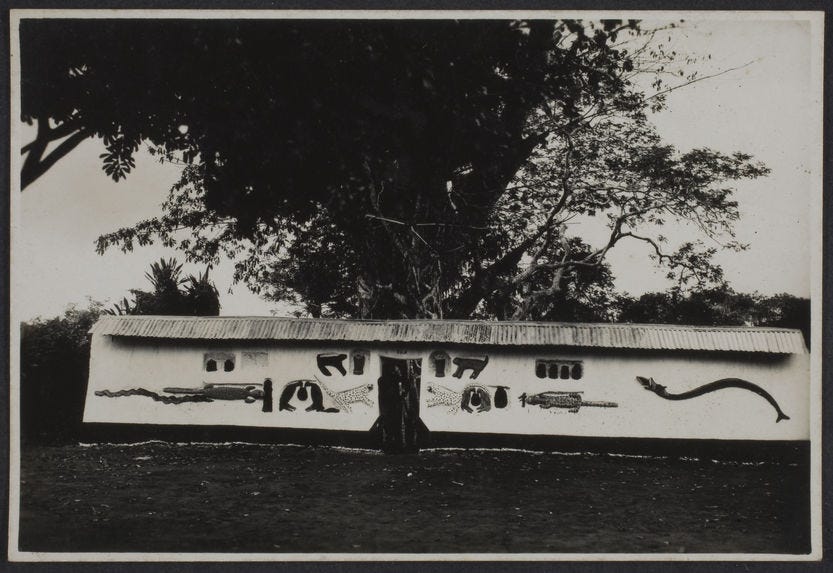

Ruins of an unidentified palace in Abomey, ca. 1894-1902. Quai branly most likely to be the simbodji palace of Gezo.

Section of the Abomey Palace complex in 1895, Quai branly.

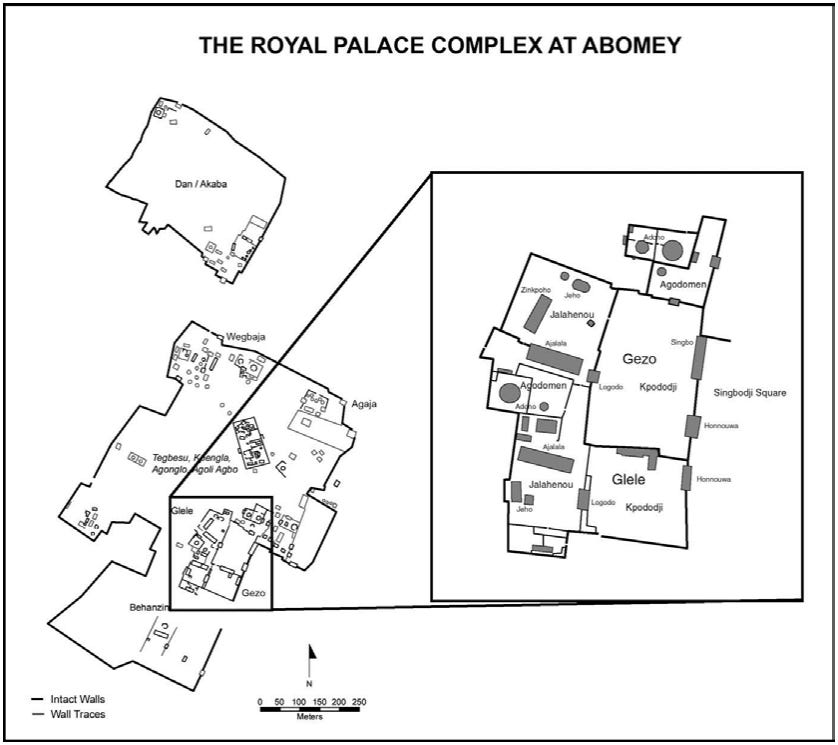

The royal palace complex at Abomey, map by J. C. Monroe

Section of the ruined palace of Agaja in 1911. The double-storey structure was built next to the palace of Akaba

Section of Agaja’s palace in 1925, Quai branly.

The royal capital of Abomey during the early 18th century

The administration of Dahomey occurred within and around a series of royal palace sites that materialized the various domestic, ritual, political, and economic activities of the royal elite at Abomey. The Abomey palace complex alone comprised about a dozen royal residences as well as many auxiliary buildings. Such palace complexes were also built in other the regional capitals across the kingdom, with as many as 18 palaces across 12 towns being built between the 17th and 19th century of which Abomey was the largest. By the late 19th century, Abomey's palace complex covered over a hundred acres, surrounded by a massive city wall about 30ft tall extending over 2.5 miles.6

These structures served as residences for the king and his dependents, who numbered 2-8,000 at Abomey alone. Their interior courtyards served as stages on which powerful courtiers vied to tip the balance of royal favor in their direction. Agaja's two story palace near the palace of Akba, and his own two-story palace within the royal complex next to Houegbadja's, exemplified the centrality of Abomey and its palaces in royal continuity and legitimation. Sections of the palaces were decorated with paintings and bas-reliefs, which were transformed by each suceeding king into an elaborate system of royal "communication" along with other visual arts.7

Abomey grew outwardly from the palace complex into the outlying areas, and was organized into quarters delimited by the square city-wall.8 Some of the quarters grew around the private palaces of the kings, which were the residences of each crown-prince before they took the throne. Added to these were the quarters occupied by the guilds/familes such as; blacksmiths (Houtondji), artists (Yemadji), weavers, masons, soldiers, merchants, etc. These palace quarters include Agaja's at Zassa, Tegbesu’s at Adandokpodji, Kpengla’s at Hodja, Agonglo’s at Gbècon Hwégbo, Gezo’s at Gbècon Hunli, Glele's at Djègbè and Behanzin's at Djime.9

illustration of Abomey in the 19th century.

illustration of Abomey’s city gates and walls, ca. 1851

interior section in the ‘private palace’ of Prince Aho Gléglé (grandson of Glele), Abomey, ca. 1930, Archives nationales d'outre-mer

Tomb of Behanzin in Abomey, early 20th century, Imagesdefence, built with the characteristic low hanging steep roof.

Abomey in the late 18th century: Religion, industry and art.

Between the end of Agaja's reign and the beginning of Tegbesu's, Dahomey became a tributary of the Oyo empire (in south-western Nigeria), paying annual tribute at the city of Cana. In the seven decades of Oyo's suzeranity over Dahomey, Abomey gradually lost its function as the main administrative capital, but retained its importance as a major urban center in the kingdom. The kings of this period; Tegbesu (r. 1740-1774), Kpengla (r. 1774-1789) and Agonglo (r. 1789-1797) resided in Agadja’s palace in Abomey, while constructing individual palaces at Cana. But each added their own entrance and reception halls, as well as their own honga (third courtyard).10

Abomey continued to flourish as a major center of religion, arts and crafts production. The city's population grew by a combination of natural increase from established families, as well as the resettlement of dependents and skilled artisans that served the royal court. Significant among these non-royal inhabitants of Dahomey were the communities of priests/diviners, smiths, and artists whose work depended on royal patronage.

The religion of Dahomey centered on the worship of thousands of vodun (deities) who inhabited the Kutome (land of the dead) which mirrored and influenced the world of the living. Some of these deities were localized (including deified ancestors belonging to the lineages), some were national (including deified royal ancestors) and others were transnational; (shared/foreign deities like creator vodun, Mawu and Lisa, the iron and war god Gu, the trickster god Legba, the python god Dangbe, the earth and health deity Sakpata, etc).11

Each congregation of vodun was directed by a pair of priests, the most influencial of whom were found in Abomey and Cana. These included practitioners of the cult of tohosu that was introduced in Tegbesu's reign. Closely associated with the royal family and active participants in court politics, Tohosu priests built temples in Abomey alongside prexisting temples like those of Mawu and Lisa, as well as the shrines dedicated to divination systems such as the Fa (Ifa of Yoruba country). The various temples of Abomey, with their elaborated decorated facades and elegantly clad tohosu priests were thus a visible feature of the city's architecture and its function as a religious center.12

Temple courtyard dedicated to Gu in the palace ground of king Gezo, ca. 1900, library of congress

entrance to the temple of Dangbe, Abomey, ca. 1945, Quai branly (the original roofing was replaced)

Practicioners of Gu and Tohusu in Abomey, ca. 1950, Quai branly

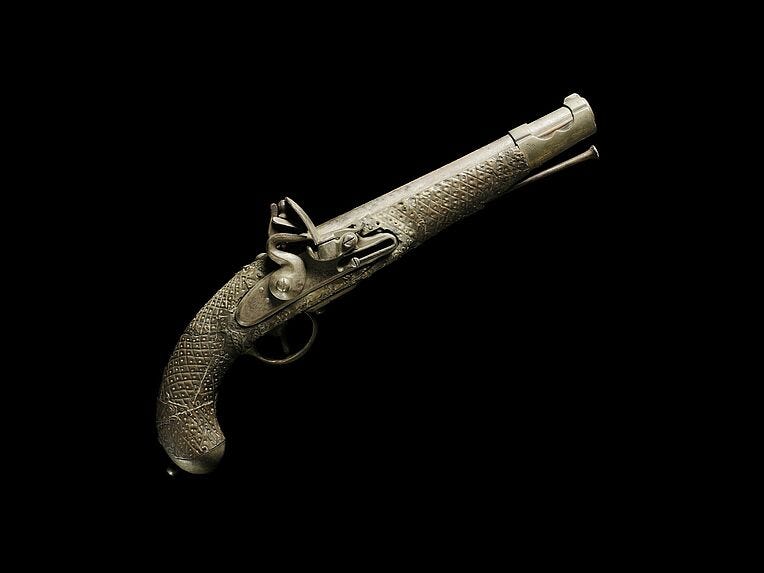

Besides the communities of priests were the groups of craftsmen such as the Hountondji families of smiths. These were originally settled at Cana in the 18th century and expanded into Abomey in the early 19th century, setting in the city quarter named after them. They were expert silversmiths, goldsmiths and blacksmiths who supplied the royal court with the abundance of ornaments and jewelery described in external accounts about Abomey. Such was their demand that their family head, Kpahissou was given a prestigious royal title due to his followers' ability to make any item both local and foreign including; guns, swords and a wheeled carriage described as a "square with four glass windows on wheels".13

The settlement of specialist groups such as the Hountondji was a feature of Abomey's urban layout. Such craftsmen and artists were commisioned to create the various objects of royal regalia including the iconic thrones, carved doors, zoomorphic statues, 'Asen' sculptures, musical instruments and figures of deities. Occupying a similar hierachy as the smiths were the weavers and embroiderers who made Dahomey's iconic textiles.

Carved blade from 19th century Abomey, Quai branly. made by the Hountondji smiths.

Pistol modified with copper-alloy plates, 1892, made by the Hountondji smiths.

Asen staff from Ouidah, mid-19th cent., Musée Barbier-Mueller, Hunter and Dog with man spearing a leopard, ca. 1934, Abomey museum. Brass sculpture of a royal procession, ca 1931, Fowler museum

Collection of old jewelery and Asen staffs in the Abomey museum, photos from 1944.

Cloth making in Abomey was part of the broader textile producing region and is likely to have predated the kingdom's founding. But applique textiles of which Abomey is famous was a uniquely Dahomean invention dated to around the early 18th century reign of Agadja, who is said to have borrowed the idea from vodun practitioners. Specialist families of embroiders, primarily the Yemaje, the Hantan and the Zinflu, entered the service of various kings, notably Gezo and Glele, and resided in the Azali quarter, while most cloth weavers reside in the gbekon houegbo.14

The picto-ideograms depicted on the applique cloths that portray figures of animals, objects and humans, are cut of plain weave cotton and sewn to a cotton fabric background. They depict particular kings, their "strong names" (royal name), their great achievements, and notable historical events. The appliques were primary used as wall hangings decorating the interior of elite buildings but also featured on other cloth items and hammocks. Applique motifs were part of a shared media of Dahomey's visual arts that are featured on wall paintings, makpo (scepters), carved gourds and the palace bas-reliefs.15 Red and crimson were the preferred colour of self-representation by Dahomey's elite (and thus its subjects), while enemies were depicted as white, pink, or dark-blue (all often with scarifications associated with Dahomey’s foe: the Yoruba of Oyo).16

Illustration showing a weaver at their loom in Abomey, ca. 1851

Cotton tunics from Abomey, 19th century, Quai branly. The second includes a red figure in profile.

Applique cloths from Abomey depicting war scenes, Quai branly. Both show Dahomey soldiers (in crimson with guns) attacking and capturing enemy soldiers (in dark blue/pink with facial scarification). The first is dated to 1856, and the second is from the mid-20th cent.

The bas-reliefs of Dahomey are ornamental low-relief sculptures on sections of the palaces with figurative scenes that recounted legends, commemorated historic battles and enhanced the power of the rulers. Many were narrative representations of specific historical events, motifs of "strong-names" representing the character of individual kings, and as mnemonic devices that allude to different traditions.17

The royal bas-relief tradition in its complete form likely dates to the 18th century during the reign of Agonglo and would have been derived from similar representations on temples, although most of the oldest surviving reliefs were made by the 19th century kings Gezo and Glele. Like the extensions of old palaces, and building of tombs and new soul-houses, many of the older reliefs were modified and/or added during the reigns of successive kings. Most were added to the two entry halls and protected from the elements by the high-pitched low hanging thatch roof which characterized Abomey's architecture.18

Reliefs on an old Temple in Abomey, ca. 1940, Quai branly.

Bas-reliefs on the reception hall of king Gezo, ca. 1900. Metropolitan Museum of Art,

Reconstruction of the reception hall, ca. 1925, Quai branly

Bas-reliefs from the palace of King Behanzin, ca. 1894-1909, Quai branly

Abomey in the 19th century from Gezo to Behanzin.

Royal construction activity at Abomey was revived by Adandozan, who constructed his palace south of Agonglo's extension of Agaja's palace. However, this palace was taken over by his sucessor; King Gezo, who, in his erasure of Adandozan's from the king list, removed all physical traces of his reign. The reigns of the 19th century kings Gezo (r. 1818-1858) and Glele (r.1858-1889) are remembered as a golden age of Dahomey. Gezo was also a prolific builder, constructing multiple palaces and temples across Dahomey. However, he chose to retain Adandozan's palace at Abomey as his primary residence, but enlarged it by adding a two-story entrance hall and soul-houses for each of his predecessors.19

Gezo used his crowned prince’s palace and the area surrounding it to make architectural assertions of power and ingenuity. In 1828 he constructed the Hounjlo market which became the main market center for Abomey, positioned adjacent and to the west of his crowned prince’s palace and directly south of the royal palace. Around this market he built two multi-storied buildings, which occasionally served as receptions for foreign visitors.20

Gezo’s sucessor, King Glele (r. 1858-1889) constructed a large palace just south of Gezo's palace; the Ouehondji (palace of glass windows). This was inturn flanked by several buildings he added later, such as the adejeho (house of courage) -a where weapons were stored, a hall for the ahosi (amazons), and a separate reception room where foreigners were received. His sucessor, Behanzin (r. 1889-1894) resided in Glele's palace as his short 3-year reign at Abomey couldn’t permit him to build one of his own before the French marched on the city in 1893/4.21

As the French army marched on the capital city of Abomey, Behanzin, realizing that continued military resistance was futile, escaped to set up his capital north. Before he left, he ordered the razing of the palace complex, which was preferred to having the sacred tombs and soul-houses falling into enemy hands. Save for the roof thatching, most of the palace buildings remained relatively undamaged. Behanzin's brother Agoli-Agbo (1894-1900) assumed the throne and was later recognized by the French who hoped to retain popular support through indirect rule. Subsquently, Agoli-Agbo partially restored some of the palaces for their symbolic and political significance to him and the new colonial occupiers, who raised a French flag over them, making the end of Abomey autonomy.22

Section of Gezo’s Simbodji Palace, illustration from 1851.

Simbodji in 1894

Simbodji in 1894-1909

Palace complex in 1896, BNF.

East of the kingdom of Dahomey was the Yoruba country of Oyo and Ife, two kingdoms that were home to a vibrant intellectual culture where cultural innovations were recorded and transmitted orally;

read more about it here in my latest Patreon article;

map by J.C.Monroe

The Precolonial State in West Africa: Building Power in Dahomey by J. Cameron Monroe pg 36-41)

Razing the roof : the imperative of building destruction in dahomè by S. P. Blier pg 165-174, The Royal Palace of Dahomey: symbol of a transforming nation by Lynne Ann Ellsworth Larsen pg 11, 21-24, Wives of leopard by Edna Bay pg 50)

The Royal Palace of Dahomey: symbol of a transforming nation by Lynne Ann Ellsworth pg 28-30)

Razing the roof : the imperative of building destruction in dahomè by S. P. Blier pg 174-175)

Wives of leopard by Edna Bay pg 9, The Precolonial State in West Africa by J. Cameron Monroe pg 24-25)

The Precolonial State in West Africa by J. Cameron Monroe pg 21, The Royal Palace of Dahomey: symbol of a transforming nation by Lynne Ann Ellsworth pg 37,43-44)

Razing the roof : the imperative of building destruction in dahomè by S. P. Blier pg 173-175)

The Royal Palace of Dahomey: symbol of a transforming nation by Lynne Ann Ellsworth pg 164-172)

The Royal Palace of Dahomey: symbol of a transforming nation by Lynne Ann Ellsworth pg 47-53)

Wives of leopard by Edna Bay pg 21-24, 62)

Wives of leopard by Edna Bay pg 91-96)

Asen, Ancestors, and Vodun By Edna G. Bay pg 55- 66

Museums & History in West Africa By West African Museums Programme, pg 78-81)

The art of dahomey Melville J. Herskovits pg 70-74

African Vodun: Art, Psychology, and Power by S. P. Blier pg 323-326)

Palace Sculptures of Abomey by Francesca Piqué pg 49-75, Asen, Ancestors, and Vodun By Edna G. Bay pg 96-98, )

The Royal Palace of Dahomey: symbol of a transforming nation by Lynne Ann Ellsworth pg 12-14, 28, 37, 56-61, 69)

The Royal Palace of Dahomey: symbol of a transforming nation by Lynne Ann Ellsworth pg 61-62, 66-69)

The Royal Palace of Dahomey: symbol of a transforming nation by Lynne Ann Ellsworth pg 173)

The Royal Palace of Dahomey: symbol of a transforming nation by Lynne Ann Ellsworth pg 72-74, 82)

"Le Musée Histoire d'Abomey" by S. P. Blier pg 143-144)