a complete history of Mombasa ca. 600-1895.

Journal of African cities: chapter 13

The island of Mombasa is home to one of the oldest cities on the East African coast and is today the largest seaport in the region.

Mombasa’s strategic position on the Swahili Coast and its excellent harbours were key factors in its emergence as a prosperous city-state linking the East African mainland to the Indian Ocean world.

Its cosmopolitan community of interrelated social groups played a significant role in the region's history from the classical period of Swahili history to the era of the Portuguese and Oman suzerainty, contributing to the intellectual and cultural heritage of the East African coast.

This article outlines the history of Mombasa, exploring the main historical events and social groups that shaped its history.

Map of Mombasa and the Swahili coast.

Support AfricanHistoryExtra by becoming a member of our Patreon community, subscribe here to read more about African history, download free books, and keep this newsletter free for all:

The early history of Mombasa: 6th-16th century.

The island of Mombasa was home to one of the oldest Swahili settlements on the East African coast. Excavations on Mombasa Island reveal that it was settled as early as the 6th-9th century by ironworking groups who used ‘TT’/’TIW’ ceramics characteristic of other Swahili settlements. An extensive settlement dating from 1000CE to the early 16th century was uncovered at Ras Kiberamni and the Hospital site to its south, with the latter site containing more imported pottery and the earliest coral-stone constructions dated to the early 13th century.1

The first documentary reference to Mombasa comes from the 12th-century geographer Al-Idrisi, who notes that it was located two days sailing from Malindi, and adds that “It is a small town of the Zanj and its inhabitants are engaged in the extraction of iron from their mines… in this town is the residence of the king of the Zanj.” The globe-trotter Ibn Battuta, who visited Mombasa in 1332, described it as a large island inhabited by Muslim Zanj, among whom were pious Sunni Muslims who built well-constructed mosques, and that it obtained much of its grain from the mainland.2

The 19th-century chronicle of Mombasa and other contemporary accounts divide its early history into two periods associated with two dynasties and old towns. It notes that the original site known as Kongowea was a pre-Islamic town ruled by Queen Mwana Mkisi. She/her dynasty was succeeded by Shehe Mvita, a Muslim ‘shirazi’ at the town of Mvita which overlapped with Kongowea and was more engaged in the Indian Ocean trade. Such traditions compress a complex history of political evolution, alliances, and conflicts between the various social groups of Mombasa which mirrors similar accounts of the evolution of the Swahili's social history.3

street in Mombasa Kenya showing the 16th-century Mandhry Mosque, ca. 1940, Mary Evans Picture Library.

types of ‘Souahheili’ from Zanzibar, Lamu, Mombasa, Pate; ca. 1846-48, Lithograph by A. Bayot & Charles Guillain. “Highbred Swahili” in Mombasa, Kenya, ca.1900-1914, USC Libraries. Street in Mombasa, Kenya, ca.1900-1914.

Sections of Old town Mombasa and other streets, ca. 1927-1940, Mary Evans Picture Library.

Like most Swahili cities, Mombasa was governed like a "republic" led by a tamim (erroneously translated as King or Sultan) chosen by a council of sheikhs and elders (wazee). Between the 15th and 17th century, Mombasa’s residents gradually began forming into two confederations (Miji), consisting of twelve clans/tribes (Taifa) that included pre-existing social groups and others from the Swahili coast and mainland. One of the confederations that came to be known as Tissia Taifa (nine clans4) occupied the site of Mvita, and were affiliated with groups from the Lamu archipelago. The second confederation had three clans5, Thelatha Taifa, and is associated with the sites of Kilindini and Tuaca.6

Archeological surveys at the site of Tuaca revealed remains of coral walls with two phases of construction, as well as local pottery and imported wares from the Islamic world and China. A gravestone possibly associated with a ruined mosque in the town bore the inscription ‘1462’. Other features of Tuaca include a demolished ruin of the Kilindini mosque, also known as Mskiti wa Thelatha Taita (Mosque of the Three Tribes); the remains of the town wall and a concentration of baobab trees.7

Later accounts and maps from the 17th century identify ‘Tuaca’ as a large forested settlement with a harbor known as ‘Barra de Tuaca’, next to a pillar locally known as Mbaraki. Excavations at the mosque next to the Mbaraki pillar indicate that the mosque was built in the 15th century before it was turned into a site for veneration in the 16th century, with the pillar being constructed by 1700.8 A much older pillar which is noted in the earliest Portuguese account of Mombasa may have been the minaret of the Basheikh mosque.9

The Basheikh Mosque and Minaret, ca. 1910, The Mbaraki Pillar, ca. 1909-1921, Mary Evans Picture Library.

Mombasa, ca. 1572 by Georg Braun and Frans Hogenberg

1462 epitaph of 'Mwana wa Bwana binti mwidani', from the Tuaca town in Mombasa, Kenya, Fort Jesus Museum10

Mombasa during the 16th century: Conflict with Portugal and the ascendancy of Malindi.

In April 1498 Vasco da Gama arrived at Mombasa but the encounter quickly turned violent once Mombasa’s rulers became aware of his actions on Mozambique island, so his crew were forced to sail to Malindi. This encounter soured relations between Mombasa and the Portuguese, and the latter’s alliance with Malindi would result in three major invasions of the city in 1505, 1526, 1589, and define much of the early Luso-Swahili history.

At the time of the Portuguese encounter, Mombasa was described as the biggest of the three main Swahili city-states; the other two being Kilwa and Malindi. It had an estimated population of 10,000 who lived in stone houses some up to three stories high with balconies and flat roofs, interspaced between these were houses of wood and narrow streets with stone seats (baraza). Mombasa was considered to be the finest Swahili town, importing silk and gold from Cambay and Sofala.11

According to Duarte Barbosa the king of Mombasa was "the richest and most powerful" of the entire coast, with rights over the coastal towns between Kilifi and Mutondwe. A later account from the 1580s notes that the chief of Kilifi was a "relative" of the king of Mombasa. Barbosa also mentions that "Mombasa is a place of great traffic and a good harbour where small crafts and great ships were moored, bound to Sofala, Cambay, Malindi and other ports."12

the 15th-century ruins of Mnarani, one of the three towns that formed the city of Kilifi.13

An account from 1507 notes the presence of merchants from Mombasa as far south as the Kerimba archipelago off the coast of Mozambique. They formed a large community that was supported by the local population and even had a kind of factory where ivory was stored. Another account from 1515 mentions Mombasa among the list of Swahili cities whose ships were sighted in the Malaysian port city of Malacca, along with ships from Mogadishu, Malindi, and Kilwa.14

The rulers of Mombasa and the city-state of Kilwa maintained links through intermarriage and the former may have been recognized as the suzerain of Zanzibar (stone-town). The power of Mombasa and the city-state's conflict with Malindi over the region of Kilifi compelled the Malindi sultan to ally with the Portuguese and break the power of Mombasa and its southern allies. Malindi thus contributed forces to the sack of Mombasa in 1505, and again in 1528-1529 when a coalition of forces that included Pemba and Zanzibar attacked Mombasa and its allies in the Kerimba islands.15

Despite the extent of the damage suffered during the two assaults, the city retained its power as most of its population often retreated during the invasions. It was rebuilt in a few years and even further fortified enough to withstand a failed attack in 1541. Tensions between Mombasa and the Portuguese subsided as the latter became commercial allies, but the appearance of Ottomans in the southern read sea during this period provided the Swahili a powerful ally against the Portuguese.16

Around 1585, the Ottoman captain Ali Bey sailed down the coast from Aden and managed to obtain an alliance with many Swahili cities, with Mombasa and Kilifi sending their envoys in 1586 just before he went back to Aden. Informed by Malindi on the actions of Ali Bey, the Portuguese retaliated by attacking Mombasa in 1587 and forcing its ruler to submit. When Ali Bey's second fleet returned in 1589, it occupied Mombasa and fortified it.17

Shortly after Ali Bey's occupation of Mombasa, the Zimba, an enigmatic group from the mainland that had fought the Portuguese at Tete in Mozambique, arrived at Mombasa and besieged the city. In the ensuing chaos, the Zimba killed the Mombasa sultan and Ottomans surrendered to the Portuguese, before the Zimba proceeded to attack Malindi but were repelled by the Segeju, a mainland group allied to Malindi. In 1589 the Segeju attacked both Kilifi and Mombasa, and handed over the latter to the Sultan Mohammed of Malindi. The Portuguese then made Mombasa the seat of the East African possessions in 1593, completed Fort Jesus in 1597, and granted the Malindi sultan 1/3rd of its customs.18

Fort Jesus & Mombasa Harbour, Northwestern University Libraries, ca. 1890-1939.

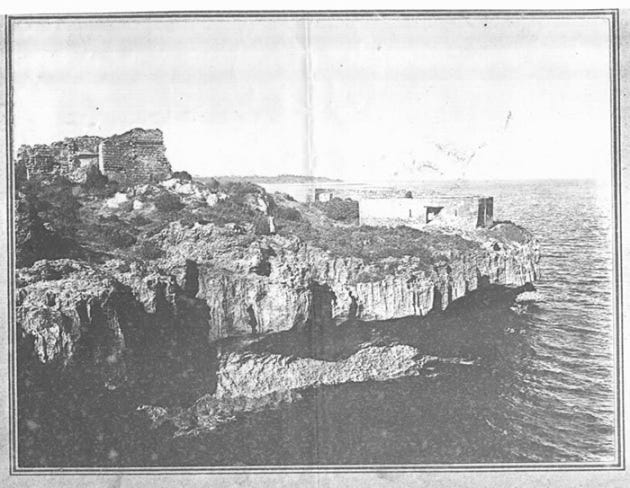

The Horse-shoe fort and the ruin of the Portuguese Chapel at the left, ca. 1910.

Mombasa during the Portuguese period: 1593-1698.

The Portuguese established a settler colony populated with about 100 Portuguese adults and their families at the site known as Gavana. These colonists included a few officers, priests who ran mission churches, soldiers garrisoned in the fort, and casados (men with families). The Swahili and Portuguese of Mombasa were engaged in ivory and rice trade with the mainland communities of the Mijikenda (who appear in Portuguese documents as the "Nyika" or as the "mozungulos"), which they exchanged for textiles with Indian merchants from Gujarat and Goa, with some wealthy Swahili from Mombasa such as Mwinyi Zago even visiting Goa in 1661.19

Relations between the Malindi sultans and the Portuguese became strained in the early 17th century due to succession disputes and regulation of trade and taxes, in a complex pattern of events that involved the Mijikenda who acted as military allies of some factions and the primary supplier of ivory from the mainland.20 This state of affairs culminated in the rebellion of Prince Yusuf Hasan (formerly Dom Jeronimo Chingulia) who assassinated the captain of Mombasa and decimated the entire colony by 1631. His reign was shortlived, as the Portuguese returned to the city by 1632, forcing Yusuf to flee to the red sea region, marking the end of the Malindi dynasty at Mombasa.21

Old Mombasa Harbour, ca. 1890-1939, Northwestern University.

Near the close of the 17th century however, the Portuguese mismanagement of the ivory trade from the mainland forced a section of the Swahili of Mombasa to request military aid from Oman. Contemporary accounts identify a wealthy Swahili merchant named Bwana Gogo of the Tisa Taifa faction associated with Lamu, and his Mijikenda suppliers led by 'king' Mwana Dzombo, as the leaders of the uprising, while most of the Thelatha Taifa and other groups from Faza and Zanzibar allied with the Portuguese.22

A coalition of Swahili and Omani forces who'd been attacking Portuguese stations along the coast eventually besieged Mombasa in 1696. After 33 months, the Fort was breached and the Portuguese were expelled. The Omani sultans placed garrisons in Mombasa, appointing the Mazrui as local administrators.23

Plan of the fort of Monbaco, ca. 1646, British Library. showing Tuaca (above Fort Jesus), the forested section of Kilindi in the middle, the Portuguese colony (Gavana) next to Fort jesus, and Mvita/‘Old Town’ next to it.

Mombasa during the Mazrui era (1735-1837)

Conflicts between the Swahili and Omanis in Pate and Mombasa eventually compelled the former to request Portuguese aid in 1727 to expel the Omanis. By March of 1729, the Portuguese had reoccupied Fort Jesus with support from Mwinyi Ahmed of Mombasa and the Mijikenda. However, the Portuguese clashed with their erstwhile allies over the ivory and textile trade, prompting Mwinyi Ahmed and the Mijikenda to expel them by November 1729. He then sent a delegation to Muscat with the Mijikenda leader Mwana Jombo to invite the Yarubi sultan of Oman back to Mombasa. The Yarubi Omanis thereafter appointed Mohammed bin Othman al-Mazrui as governor (liwali) in 1730, but a civil war in Oman brought the Busaidi into power and the Mazrui refused to recognize their new suzerains and continued to rule Mombasa autonomously.24

During the Mazrui period, most of the population was concentrated at Mvita and Kilindini while Gavana and Tuaca were largely abandoned. The Mazrui family integrated into Swahili society but, aside from arbitrating disputes, their power was quite limited and they governed with the consent of the main Swahili lineages. For example in 1745 after the Busaidi and their allies among the Tisa Taifa assassinated and replaced the Mazrui governor of Mombasa, sections of the Thelatha Taifa and a section of the Mijikenda executed the briefly-installed Busaidi governor and restored the Mazrui.25

Persistent rivalries between the governing Mazrui and the Tisa Taifa forced the Mazrui to get into alot of debt to honour the multiple gifts required by their status. Some of the Mazrui governors competed with the sultans of Pate, who thus allied with the Tisa Taifa against the Thelatha Taifa. Both sides installed and deposed favorable rulers in Mombasa and Pate, fought for control over the island of Pemba, and leveraged alliances with the diverse communities of the Mijikenda.26

Mombasa continued to expand its links with the Mijikenda, who provided grain to the city in exchange for textiles and an annual custom/tribute that in the 1630s constituted a third of the revenue from the customs of Fort Jesus. The Mijikenda also provided the bulk of Mombasa's army, and the city's rulers were often heavily dependent on them, allowing the Mijikenda to exert significant influence over Mombasa's politics and social life, especially during the 18th century when they played kingmaker between rival governors and also haboured belligerents. Some of them, eg the Duruma, settled in Pemba where they acted as clients of the Mazrui.27

Some of the earliest Swahili-origin traditions were recorded in Mombasa in 1847 and 1848, they refer to the migration of the Swahili from the city/region of Shungwaya (which appears in 16th-17th century Portuguese accounts and corresponds to the site of Bur Gao on the Kenya/Somalia border) after it was overrun by Oromo-speaking herders allied with Pate. These Swahili then moved to Malindi, Kilifi, and finally to Mombasa, revealing the extent of interactions between the mainland and the island and the fluidity of Mombasa’s social groups. At least four of the clans of Mombasa, especially among the Thelatha Taifa claim to have been settled on the Kenyan mainland before moving to the island.28

Mombasa and environs in the 19th century. Mvita: TisaTaifa settlement. Kilindini: Thelatha Taifa settlement. Likoni: Kilindini clan of Thelatha Taifa; Mtongwe: Tangana clan of Thelatha Taifa; Ngare: Changamwe clan of Thelatha Taifa; Jomvu kwa Shehe, Maunguja, and Junda: Jomvu clan of Tisa Taifa.29

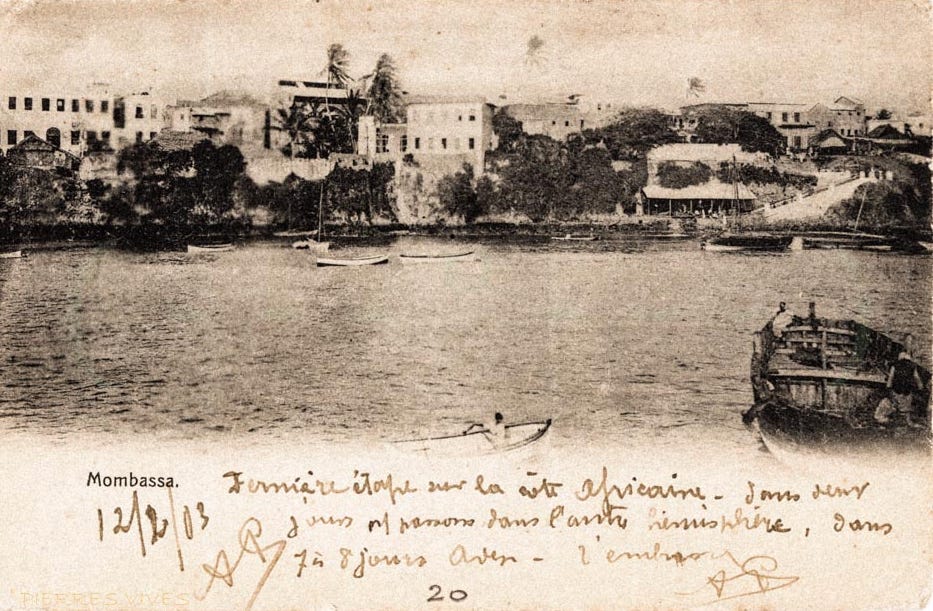

Mombasa, ca. 1903, OldEastAfricaPostcards.

Mombasa under the Mazrui expanded its control from Tanga to the Bajun islands and increased its agricultural tribute from Pemba, which in the 16th-17th century period amounted to over 600 makanda of rice, among other items, (compared to just 20 makanda from the Mijikenda).30 This led to a period of economic prosperity that was expressed in contemporary works by Mombasa’s scholars. Internal trade utilized silver coins (thalers) as well as bronze coins that were minted during the governorship of Salim ibn Ahmad al-Mazrui (1826–1835).31

In the late 18th century, Mombasa's external trade continued to be dominated by ivory and other commodities like rice, that were exported to south Arabian ports. However, Mombasa's outbound trade was less than that carried out by Kilwa, Pemba, and Zanzibar, whose trade was directed to the Omans of Muscat, who were hostile to the Mazrui. Mombasa also prohibited trade with the French who wanted captives for their colony in the Mascarenes, as they were allied with the Portuguese, leaving only the English who purchased most of Mombasa's ivory for their possessions in India.32

The city was part of the intellectual currents and wealth of the 18th century and early 19th century, which contributed to a Swahili ‘renaissance,’ that marked the apex of classical Swahili poetry with scholars from Pate and Mombasa such as Seyyid Ali bin Nassir (1720–1820), Mwana Kupona (d. 1865) and Muyaka bin Haji (1776–1840), some of whose writings preserve elements of Mombasa’s early history33

Hamziyya, copied by Abī Bakr bin Sulṭān Aḥmad in 1894 CE, with annotations in Swahili and Arabic. Private collection of Sayyid Ahmad Badawy al-Hussainy (1932-2012) and Bi Tume Shee, Mombasa. The Mombasa chronicle, written by Khamis al-Mambasi in the 19th century. SOAS library.

Mombasa in the 19th century: from Mazrui to the Busaid era (1837-1895)

At the start of the 19th century, internal and regional rivalries between the elites of Mombasa, Pate, and Lamu, supported by various groups on the mainland culminated in a series of battles between 1807 and 1813, in which Lamu emerged as the victor, and invited the Busaidi sultan of Oman, Seyyid Said as their protector, who later moved his capital from Muscat to Zanzibar.34

Internecine conflicts among the Mazrui resulted in a breakup of their alliance with the Thelatha Taifa, some of whom shifted their alliance to the Zanzibar sultan Sayyid Said, culminating in the latter’s invasion of Mombasa in 1837, and the burning of Kilindini town. The Thelatha Taifa then established their own area in Mvita known as Kibokoni, adjacent to the Mjua Kale of the Tissa Taifa to form what is now the ‘Old Town’ section of the city.35

Under the rule of the Zanzibar sultans, the Swahili of Mombasa retained most of their political autonomy. They elected their own leaders, had their own courts that settled most disputes within the section, and they only paid some of the port taxes and tariffs to Zanzibar.36

By the late 19th century, the expansion of British colonialism on the East African coast eroded the Zanzibar sultan’s authority, with Mombasa eventually becoming part of the British protectorate in 1895. Economic and political changes as well as the arrival of new groups from India, Yemen, and the Kenyan mainland during the colonial period would profoundly alter the social mosaic of the cosmopolitan city, transforming it into modern Kenya’s second-largest city.37

Mombasa, Kenya, ca. 1890, Northwestern University

Mombasa derived part of its wealth from re-exporting the gold of Sofala, which was ultimately obtained from Great Zimbabwe and the other stone-walled capitals of Southeast Africa

Please subscribe to read about the history of the Gold trade of Sofala and the internal dynamics of gold demand within Southeast Africa and the Swahili coast here:

The Swahili World, edited by Stephanie Wynne-Jones, Adria LaViolette pg 621, Excavations at the Site of Early Mombasa by Hamo Sassoon.

Excavations at the Site of Early Mombasa by Hamo Sassoon pg 3-5

Oral Historiography and the Shirazi of the East African Coast by Randall L. Pouwels pg 252-253, The Swahili World, edited by Stephanie Wynne-Jones, Adria LaViolette pg 52)

These are the; Mvita, Jomvu, Kilifi, Mtwapa, Pate, Shaka, Paza, Bajun, and Katwa.

These are the Kilindini, Changamwe, and Tangana.

The Way the World Is: Cultural Processes and Social Relations Among the Mombasa Swahili by Marc J. Swartz pg 30-33, The Swahili World, edited by Stephanie Wynne-Jones, Adria LaViolette pg 621, 76)

The Swahili World, edited by Stephanie Wynne-Jones, Adria LaViolette pg 621-622)

The Swahili World, edited by Stephanie Wynne-Jones, Adria LaViolette pg 622, Mbaraki Pillar & Related Ruins of Mombasa Island by Hamo Sassoon

Excavations at the Site of Early Mombasa by Hamo Sassoon pg 7

Mombasa Island: A Maritime Perspective by Rosemary McConkey and Thomas McErlean pg 109

Excavations at the Site of Early Mombasa by Hamo Sassoon pg 7

Les cités-États swahili de l'archipel de Lamu, 1585-1810: dynamiques endogènes, dynamiques exogènes by Thomas Vernet pg 60-61, 331, The Swahili World, edited by Stephanie Wynne-Jones, Adria LaViolette pg 620)

Mnarani of Kilifi: The Mosques and Tombs by James Kirkman

East Africa and the Indian Ocean by Edward A. Alpers pg 9, Les cités-États swahili de l'archipel de Lamuby Thomas Vernet pg 75, 83)

The Medieval Foundations of East African Islam by Randall L. Pouwels pg 404-406, Les cités-États swahili de l'archipel de Lamu, 1585-1810 by Thomas Vernet pg 64-65, 83-84)

Les cités-États swahili de l'archipel de Lamu, 1585-1810 by Thomas Vernet pg 85-86, 89, 97)

Global politics of the 1580s by G Casale pg 269-273, Les cités-États swahili de l'archipel de Lamu, 1585-1810 by Thomas Vernet pg 100-108)

Les cités-États swahili de l'archipel de Lamu, 1585-1810 by Thomas Vernet pg 109- 125)

Les cités-États swahili de l'archipel de Lamu, 1585-1810 by Thomas Vernet pg 127-140, 150, 152, 225-227, Mombasa Island: A Maritime Perspective by Rosemary McConkey and Thomas McErlean pg 111-113.

Les cités-États swahili de l'archipel de Lamu, 1585-1810 by Thomas Vernet pg 414-416)

Empires of the Monsoon by Richard Seymour Hall pg 266-274.

Les cités-États swahili de l'archipel de Lamu, 1585-1810 by Thomas Vernet pg 365-373)

The Swahili World, edited by Stephanie Wynne-Jones, Adria LaViolette pg 522-523)

Les cités-États swahili de l'archipel de Lamu, 1585-1810 by Thomas Vernet pg 434-460)

Mombasa, the Swahili, and the making of the Mijikenda by Justin Willis pg 59-60, The Swahili community of Mombasa by J. Berg pg 50-52

Oral Historiography and the Shirazi of the East African Coast by Randall L. Pouwels pg 253, Les cités-États swahili de l'archipel de Lamu, 1585-1810 by Thomas Vernet pg 266, 469-472, The Way the World Is: Cultural Processes and Social Relations Among the Mombasa Swahili by Marc J. Swartz pg 34.

by the 20th century, the Mijikenda were divided into nine groups; Giriama, Digo, Rabai, Chonyi, Jibana, Ribe, Kambe, Kauma and Duruma, some of whom, such as the Duruma and Rabai appear in much earlier sources.

Les cités-États swahili de l'archipel de Lamu, 1585-1810 by Thomas Vernet pg 261-264, 413-415, 528-529)

Les cités-États swahili de l'archipel de Lamu, 1585-1810 by Thomas Vernet pg 229-231, 231-235, 315-316, The Swahili community of Mombasa by J. Berg pg 46-49.

The Swahili community of Mombasa by J. Berg pg 49

Les cités-États swahili de l'archipel de Lamu, 1585-1810 by Thomas Vernet pg 336-338)

The Swahili World, edited by Stephanie Wynne-Jones, Adria LaViolette pg 454-455, The Swahili community of Mombasa by J. Berg 52

Les cités-États swahili de l'archipel de Lamu, 1585-1810 by Thomas Vernet pg 476-481, The Swahili World, edited by Stephanie Wynne-Jones, Adria LaViolette pg 386)

The Swahili World, edited by Stephanie Wynne-Jones, Adria LaViolette pg 524)

The battle of Shela by RL Pouwels

The Swahili community of Mombasa by J. Berg pg 52-53, The Way the World Is: Cultural Processes and Social Relations Among the Mombasa Swahili by Marc J. Swartz pg 35.

The Swahili community of Mombasa by J. Berg pg 53-55

The Way the World Is: Cultural Processes and Social Relations Among the Mombasa Swahili by Marc J. Swartz pg 36-40.

Well done and thank you for another great article, I'm fascinated by the Wa Zimba, their terrifying martial practices, meant to shock ,intimidate and show utter contempt by reportedly cannibalizing their foes, which remind me of the later Imbangala , where did these people came from, and why were they so aggressive were they working on the behalf of another power, perhaps a great inland empire ?