A forgotten African empire: the history of medieval Kānem (ca. 800-1472)

A century before Mansa Musa’s famous pilgrimage, the political and cultural landscape of medieval West Africa was dominated by the empire of Kānem.

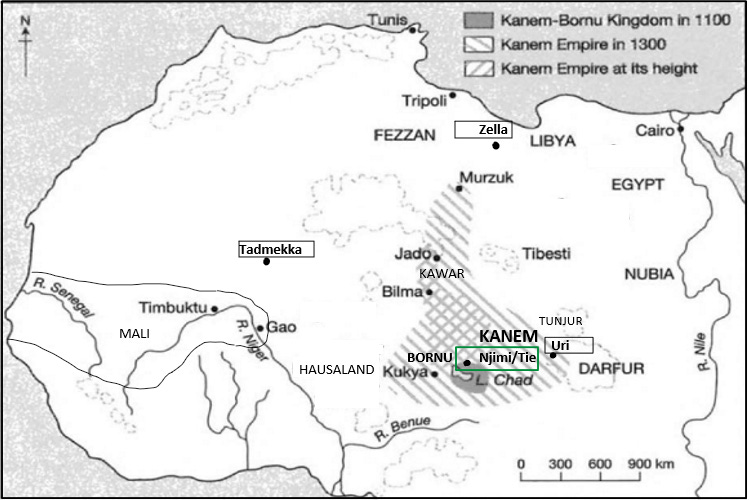

At its height in the 13th century, the empire's influence extended over a broad swathe of territory stretching from southern Libya in the north to the border of the Nubian kingdoms in the east to the cities of the eastern bend of the Niger river in the west.

Centred on Lake Chad, medieval Kānem was located at the crossroads of unique historical, cultural and economic significance for medieval and post-medieval Africa, and was one of the longest-lived precolonial states on the continent.

This article explores the history of Kanem during the middle ages, uncovering the political, intellectual and cultural history of the forgotten empire.

Map of medieval Kānem. the highlighted cities mark the limit of its area of influence during the 13th century.

Support African History Extra by becoming a member of our Patreon community, subscribe here to read more on African history and keep this blog free for all:

The early history and archeology of medieval Kānem

Kānem first appears in written sources in the account of Al-Yakubi from 872 CE, who mentions the kingdom of the Zaghawa in a place called Kanim/Kānem.1

Later accounts describe the state of Kānem [Zaghawa] as a vast empire extending from the lake Chad region to the borders of Nubia in Sudan. Writing a century later in 990 CE, al-Muhallabi mentions that :

“The Zaghawa kingdom is one of the most extensive. To the east it borders on the Nuba kingdom in Upper Egypt, and between them there is a ten-day march. They consist of many peoples. The length of their country is 15 stages as much as wide.”

Three centuries later in 1286 CE, Ibn Said comments that:

“At an angle of the lake [Chad], 51° longitude, is Matan, one of the famous towns of Kanem. South of this town is the capital of Kanem, Djimi. Here resides the sultan famous for his jihad and his acts of virtue. (...) Of this sultan depend [the countries] like the sultanate of Tadjuwa, the kingdoms of Kawar and Fazzan. (...) East of Matan, there are the territories of the Zaghawa, who are mostly Muslims under the authority of the ruler of Kanem. Between the south-east bank [of the Nile] and Tadjuwa, the capital of Zaghawa, 100 miles to go. Its inhabitants became Muslims under the authority of the sovereign of Kanem. (...) The territories of Tadjuwa and Zaghawa extend over the distance between the arc of the Nile (...).”2

The early descriptions of Kānem indicate that its rulers occupied different capitals. al-Muhallabi mentions that there were two towns in Kānem, one named Tarazki and the other Manan. al-Idrisi (1154) also mentions Manan and describes the new town of Anjimi as ‘a very small town’, while the town of Zaghawa was a well populated capital. Ibn said's account describes Manan as the pre-Islamic state capital and Anjimi/Njimi as the first Islamic state capital.3

Neither of these early Kānem capitals have been identified with complete certainty, due to the very limited level of archaeological field investigations in Kānem until very recently.

The heartland of the kingdom of Kānem was one of the earliest sites of social complexity in west Africa, with evidence of plant domestication and nucleated settlements dating back to the 2nd millenium BC. The largest of the first proto-urban settlements emerged around c. 600–400 BC in the south-western region of Lake Chad at Zilum and Gagalkura A, which were surrounded by a system of ditches and ramparts, some extending over 1km long and resembling the layout of later medieval cities like Gulfey. These early sites were suceeded in the 1st millenium CE by similary fortified and even larger settlements such as Zubo and Dorotta, which were inhabited by an estimated 9700-7,000 people.4

Magnetogram showing the outlines and arrangements of some sub-surface features as well as the location of an old ditch segment at Zilum, Nigeria. image by C. Magnavita.

Aerial photo of Gulfey, a fortified Kotoko town near the southern margins of Lake Chad, showing what Zilum may have looked like in the 6th century BC. image by C. Magnavita

None of these early sites yielded any significant finds of external material such as imported trade goods. Horses were introduced much later near the end of the 1st millenium CE, but their small size and rarity indicate that they were kept as status symbols. The combined evidence of ancient state development, extensive defensive architecture and limited external contact indicate that these features were endogenous to the early kingdoms of the lake Chad basin.5

While neolithic and early iron-age sites in the Kānem region itself were about as old as those west of the lake, large settlements wouldn’t emerge until the mid-1st to early 2nd millenium CE.6 The most significant of these are represented by a cluster of 50 fired-brick settlements (enclosures, villages and farmsteads) within a radius of 25 km around the largest central enclosure, named Tié, that is dated to 1100-1260CE. The largest sites measure between 3.2 to 0.14 ha, have rectangular, fired-brick enclosures, featuring rectangular buildings of fired bricks. The second site type are dispersed hamlets of 1 ha featuring clusters of rectangular buildings of fired brick. The third site type feature one or two rectangular buildings made of fired brick.7

The site of Tie consists of a 3.2 ha fired-brick enclosure built in the 12th-13th century and occupied until late 14th-15th century. The enclosure encompasses two Mounds; 1 and 2, the former of which conceals the ruins of a high-status firedbrick building (16.8x23.4 m) with lime-plastered interior walls, while Mound 2 is the place’s refuse heap containing local pottery and metals, and imported cowries and glass beads. These beads included the HLHA blue glass beads manufactured at the Nigerian site of Ife, as well as many from the Red sea and Indian ocean region, which were very likely transported to Lake Chad via an eastern route through Sudan rather than the better known northern route as most West African sites at the time.8

Fired-brick sites presently known in the modern Chadian provinces of Kanem and adjacent Bahr-el-Ghazal to the east of Lake Chad. The map in the inlay shows the site cluster around Tié. image by C. Magnavita

Aerial view of the ongoing excavations at the fired-brick ruins of the 12th–14th century AD site of Tié (3.2 ha), Kanem, Chad. This is the largest and one of the earliest known localities associated with the Kanem-Borno state at Lake Chad. image and caption by C. Magnavita

(L-R) Detail of the outer wall as seen at excavation units I3 and I4, Orthorectified image composite showing the preserved foundation, plinth and outer wall at the SE-corner of the building under Mound 1 (excavation unit J6). A view of the preserved outer wall, plinth and foundation of the building under Mound 1 (excavation unit J6). images and captions by C. Magnavita

Archaeologists suggest that Tie was likely the site of medieval Njimi, based on etymological and oral historical evidence from surrounding villages, all of whose names begin with the root term Tié. When the site was first surveyed in the 20th century, it was known locally as Njimi-Ye, similar to the Njímiye mentioned by the explorer Heinrich Barth in his 19th century account of Kānem's history. This implies that the root Tié of the modern villages names very probably derives from the contraction Njimi-Ye. The site of Tié and a neighbouring site of Eri, are the only two fired-brick sites in Kānem that are associated with the early Sefuwa kings of Kānem, while the rest are associated with the Bulala who forced the former group to migrate from Kānem to Bornu during the late 14th century, as explred below.9

The archaeological finds at Tie corroborate various internal and external textural accounts regarding the zenith of Kānem during the 13th century. The elite constructions at the site were built during a time of unparalleled achievements in the history of the Sultanate. Internal accounts, such as a charter (mahram) of the N’galma Duku’, which was written during the reign of Sultan Salmama (r. 1182-1210), mentions the construction of a plastered mosque similar to the elite building found at Tie. External sources, particulary Ibn Said's account, mention that Sultan Dibalami (r. 1210-1248) expanded Kānem political influence as far as Bornu (west of Chad), Fezzan (Libya) and Darfur (Sudan).10

Expansion of medieval Kānem

The northern expansion of Kānem begun with the empire's conquest of the Kawar Oases of north-eastern Niger. Al-Muhallabi's 10th century account mentions that the Kawar oases of Gasabi and Bilma as located along the route to Kānem. According to a local chronicle known as the Diwan, the Kānem ruler Mai Arku (r. 1023-1067), who was born to a Tomgara mother from Kawar, is said to have established colonies in the oases of Kawar from Dirku to Séguédine.11

Kānem’s suzeranity over Kawar during the 11th century may have been norminal or short-lived since Kawar is mentioned to be under an independent king according to al-Idrisi in the 12th century. Writing a century later however, Ibn said mentions that the Kānem king [possibly Mai Dunama Dibalami, r. 1210-1248] was in control of both Kawar and the Fezzan, he adds that “the land of the Kawar who are Muslim sudan, and whose capital is called Kawar too. At present it is subject to the sultan of Kanim.”12

Séguédine. image by Tillet Thierry13

Dabasa. image by Dierk Lange and Silvio Berthoud

Dirku.

Djado.

Kānem expansion into the Fezzan was a consequence of a power vacuum in the region that begun in 1172 when the Mamluk soldier Sharaf al-Din Qaraqush from Egypt raided the region. Having occupied Tunis and Tripoli for a brief time, Qaraqush founded a shortlived state, but was killed and crucified at the Fezzani town of Waddan in 1212. Not long after, a son Qaraqush from Egypt invaded Waddan, and according to the account of al-Tijani, “set the country ablaze. But the King of Kanem sent assassins to kill him and delivered the land from strife, his head was sent to Kanem and exhibited to the people, this happened in the year 656 AH [1258 CE].”14

Kānem’s control of the Fezzan was later confirmed by Abu’l-Fida (d. 1331) who states that the regional capital of Zawila was under Kanemi control after 1300.15 In his description of the kingdom of Kānem, al-Umari (d. 1384) writes: “The begining of his kingdom on the Egyptian side is a town called Zala and its limit in longitude is a town called Kaka. There is a distance between them of about three months' travelling.”16 Zala/Zella is located in Libya while Kaka was one of the cities west of lake chad mentioned by Ibn Said and al-Umari, and would later become the first capital of Bornu.17

Furthermore, Ibn Khaldun (d. 1406) declares that Kānem maintained friendly relations with the Hafsid dynasty of Tunis, writing that: “In the year 655 [1257] there arrived [at Tunis, the Hafsid capital] gifts from the king of Kanim, one of the kings of the Sudan, ruler of Bornu, whose domains lie to the south of Tripoli. Among them was a giraffe, an animal of strange form and incongruous characteristics.”18

Remains of old Taraghin in Libya, where the Kanem rulers established their capital by the end of the twelfth century. image and caption by J. Passon and M. Meerpohl19

Zawila. Photographs from the C.M. Daniels archive of the tombs of the Banū Khatṭạ̄ b at Zuwīla (ZUL003) in 1968 prior to restoration. image and captions by D. Mattingly et al.

The eastward expansion of Kānem which is mentioned in a few accounts has since been partially corroborated by the archaeological evidence of trade goods found at Tie that were derived from the Red sea region unlike contemporaneous west African cities like Gao that used the northern route to Libya and Morocco.

The Tadjuwa who are mentioned by Ibn Said as subjects of Kānem in its eastern most province, are recognized as the people that provided the first dynastic line of the Darfur sultanate. Later writers such as Ibn Khaldun (d. 1406) and al-Maqrizi (d. 1442) mention the Tajura/Taju/Tunjur as part of the a branch of the Zaghawa, adding a brief comment on their work in stone and warlike proclivities. Their capital of Uri first appears in the 16th century, although there were older capitals in the region.20 Some historians suggest that the eastern expansion towards Nubia was linked to Kānem’s quest for an alternate trade route, although this remains speculative.21

Proposed area of influence and trade relationships of Kanem-Borno in the thirteenth century. map by C. Magnavita et al.

The westward expansion of medieval Kānem into Bornu was likely accomplished as early as the 13th century, since the kingdom first appears in external accounts as one of the territories subject to the rulers of Kānem, although it retained most of its autonomy before the Sefuwa turned it into their base during the late 14th century.22

However, the expansion of medieval Kānem beyond Bornu is more dubious. Ibn Said’s account contains a passing reference to the town of Takedda (Tadmekka in modern Mali), which “owed obedience to Kanim.” While archeological excavations at the site of Essouk-Tadmekka have uncovered some evidence pointing to an influx of material culture from the south, the continuinity of local inscriptions and the distance between Kānem and Tadmekka make it unlikely that the empire excercised any significant authority there.23

There were strong commercial ties between Tadmekka and Kanem’s province of Bornu, as evidenced by the account of the famous globe-trotter Ibn Battuta, who visited the town in 1352. Its from Tadmekka that he gathered infromation about the ruler Kānem, who he identified as mai Idris: “who does not appear to the people and does not adress them except behind a curtain.” Ibn battuta makes no mention of Tadmekka’s suzeranity to Kanem, which by this time was at the onset of what would become a protracted dynastic conflict. 24

Ruins of Essouk-Tadmekka, Mali. image by Sam Nixon.

State and politics in medieval Kānem.

Descriptions of Kānem’s dynastic and political history at its height during the 13th and early 14th centuries come from Ibn Said, al-Umari, and Ibn Batutta who all mention that the ruler of Kānem was a ‘divine king’ who was “veiled from his people.” Ibn Said in 1269 mentions that the king is a descendant of Sayf son of Dhi Yazan, a pre-islamic Yemeni folk hero, but also mentions that his ancestors were pagans before a scholar converted his ‘great-great-great-grandfather’ to islam which indicates Kanem’s adoption of Islam in the 11th century. An anonymously written account from 1191 dates this conversion to some time after 500 [1106–1107 CE] 25

According to a local chronicle known as the Diwan which was based on oral kinglists from the 16th century that were transcribed in the 19th century, Kānem’s first dynasty of the Zaghawa was in the 11th century displaced by a second dynasty known as the Sefuwa, before the latter were expelled from Kanem in the late 14th century.26

As part of the rulers’ evolving fabrications of descent from prestigious lineages, the chronicle links them to both the Quraysh tribe of the Prophet and the Yemeni hero Sayf. However, these claims, which first appear in a letter from Kānem’ sultan ‘Uthman to the Mamluk sultan Barquq in 1391 CE, were rejected by the Egyptian chronicler Al-Qalqashandi. Additionally, the 13th century account of Ibn Said instead directly links the Sefuwa to the Zaghawa, mentioning that Mai Dunama Dibalami (r. 1210-48) resided in Manan, “the capital of his pagan ancestors.” Seemingly reconciling these conflicting claims, the Diwan also mentions that the Sefuwa rulers were ‘black’ by the reign of Mai Salmama (r. 1182-1210). The historian Augustin Holl argues that these claims were ideological rather than accurate historical geneaologies.27

According to al-Maqrizi (d. 1442) the armies of Kānem “including cavalry, infantry, and porters, number 100,000.” The ruler of Kānem had many kings under his authority, and the influence of the empire was such that the political organisation of almost all the states in the lake Chad basin was directly or indirectly borrowed from it. While little is known of its internal organisation during this period, the development a fief-holding aristocracy, an extensive class of princes (Maina), appointed village headmen (Bulama), and a secular and religious bureaucracy with Wazir, Khazin, Talib, and Qadis that are known from Bornu and neighbouring states were likely established during the Kanem period.28

Kānem controlled the Fazzan through a subordinate king or a viceroy, known as the Banū Nasr, whose capital was at Tarajin/Traghen near Murzuq. The few accounts of medieval Kānem’s suzeranity over the Fezzan come from much later in the 19th century writings of the German traveller Gustav Nachtigal who mentions that traditions of Kanem's rule were still recalled in the region, and that there were landmarks associated with Kānem, including “many gardens, open areas and wells, which today [1879] still bear names in the Kanuri language, i.e. the tongue of Kanem and Bornu.”29

Both external and internal accounts indicate that Kānem was a multi-ethnic empire. The Diwan in particular mentions that in the early period of Kānem between the 10th and 13th centuries, the queen mothers were derived from the Kay/Koyama, Tubu/Tebu, Dabir and Magomi, before the last group had grown large enough to become the royal lineage of the Sefuwa. All of these groups are speakers of the Nilo-Saharan languages and lived in pre-dominantly agro-pastoralist societies, with a some engaged in trade, mining, and crafts such as the production of textiles.30

Trade and economy in medieval Kānem

Despite the often-emphasized importance of long-distance trans-Saharan slave trade between medieval Kānem and Fezzan in the modern historiography of the region, contemporary accounts say little about trade between the two regions.

The 12th century account of al-Idrisi for example, makes no mention of carravan trade from Kānem to Fezzan through Kawar, despite the last region being the sole staging post between the two, and the Fezzan capital of Zawila being at its height. He mentions that the former Kānem capital of Manan as “a small town with industry of any sort and little commerce” and of the new capital of Njimi, he writes: “They have little little trade and manufacture objects with which they trade among themselves”. His silence on Kānem’s trade is perhaps indicative of the relative importance of regional trade in local commodities like salt and alum.31

In the same text, al-Idrisi’s description of Kawar the oases of Djado, Kalala, Bilma links their fortunes to the exploitation of alum and salt, while Al-Qaṣaba was the only town whose fame is solely due to trade. Alum is used for dyeing and tanning, the importance of these two commodities to Kawar would continue well into the modern era*. He also mentions that alum traders from Kalala travelled as far west as Wargla and as far east as Egypt, but is also silent regarding the southbound salt trade from Kawar to Kanem, which is better documented during the Bornu period.32

[* On kawar’s political and economic history: the Kawar oasis-towns from 850-1913 ]

Saltpans of Bilma

Regarding the Kānem heartland itself, the 14th century account of Al-Umari notes that “Their currency is a cloth that they weave, called dandi. Every piece is ten cubits long. They make purchases with it from a quarter of a cubit upwards. They also use cowries, beads, copper in round pieces and coined silver as currency, but all valued in terms of that cloth.” He adds that “they mostly live on rice, wheat and sorghum” and mentions, with a bit of exagerration, that “rice grows in their country without any seed.” An earlier account by al-Muhallabi (d. 990CE), also emphasizes that Kanem had a predominatly agro-pastoral economy, writing that the wealth of the king of the Kānem consists of “livestock such as sheep, cattle, camels, and horses.”33

The account of the globetrotter Ibn Batutta brifely mentions regional trade between Bornu [a Kānem province] and Takedda on the eastern border of medieval Mali, inwhich slaves and “cloth dyed with saffron” from the former were exchanged for copper from the latter.34 The contemporary evidence thus indicates that the economy of medieval Kānem owed its prosperity more to its thriving cereal agriculture, stock-raising, textile manufacture and regional trade than to long-trade across the Sahara, which may have expanded much later.

Copper-alloy and silver coins from medieval Essouk-Tadmekka, images by Sam Nixon. copper from Tadmekka was traded in Kanem and silver coins were also used as currency in the empire. Both could have been obtained from this town.

The glass beads from Tié. image by C. Magnavita et al. the largest blue beads; 22 & 34, were manufactured in the medieval city of Ile-ife in Nigeria, providing further evidence for regional trade that isn’t documented in external accounts.

An intellectual history of medieval Kanem.

Kānem was one of the earliest and most significant centers of islamic scholarship in west Africa. Its rulers are known to have undertaken pilgrimage since the 11th century, and produced west Africa's first known scholar; Ibrāhīm al-Kānimī (d. 1212) who travelled as far as Seville in muslim spain (Andalusia). Al-Umari mentions that the people of Kānem “have built at Fustat, in Cairo, a Malikite madrasa where their companies of travelers lodge.” The same madrasa is also mentioned by al-Maqrīzī (d. 1442) who calls it Ibn Rashīq, and dates its construction to the 13th century during the reign of Dunama Dabalemi.35

The intellectual tradition of Kānem flourished under its expansionist ruler Dunama Dabalemi, who is considered a great reformer, with an entourage that included jurists. Al-Umari mentions that “Justice reigns in their country; they follow the rite of imam Malik.” Evidence for Mai Dunama’s legacy is echoed in later internal chronicles such as the Diwan and the Bornu chronicle of Ibn Furtu, which accuse the sultan of having destroyed a sacred object called ‘mune’ which may have been a focal element of a royal cult from pre-Islamic times. While he was an imam, Ibn Furtu sees this ‘sacrilegious act’ as the cause of later dynastic conflicts that plagued Kānem.36

The abovementioned letter sent by the Sefuwa sultan ʿUthmān b.Idrīs to Mamluk Egypt in 1391 also demonstrates the presence of sophisticated scribes and a chancery in medieval Kānem. This is further evidenced by a the development of the barnāwī script in Kānem and Bornu —a unique form of Arabic script that is only found in the lake Chad region. The script is of significant antiquity, being derived from Kufic, and was contemporaneous with the development of the more popular maghribī script after the 11th/12th centuries that is found in the rest of west Africa.37

While the oldest preserved manuscript from Bornu is dated to 1669, the glosses found in the manuscript and others from the 17th-18th century were written in Old Kanembu. The latter is an archaic variety of Kanuri that was spoken in medieval Kānem that become a specialised scribal language after the 15th century. A modernized variety of Old Kanembu has been preserved in modern-day Bornu in a form of language known locally as Tarjumo which functions as an exegetical language for Kanuri-speaking scholars.38

The rulers of Kānem generously supported scholars by issuing mahrams that encouraged the integration intellectual diasporas from west africa and beyond. A mahram was a charter of privilege and exemption from taxation and other obligations to the rulers of Kanem and Bornu that were granted as rewards for services considered vital to the state, such as managing the chancery, teaching royals, serving at the court. They were meant for the first beneficiary and his descendants, and were thus preserved by the recepient family which periodically sought their renewal on the accession of a new ruler. The earliest of these were issued in the 12th century, indicating that this unique institution which prolifilerated in the Bornu period, was established duing the middle ages.39

17th century Quran with Kanembu glosses, Bibliothèque nationale de France, MS.Arabe 402, 17th-18th century, Qur’an copied in Konduga, Bornu, private collection, MS.5 Konduga, 18th-19th century Bornu Quran, With marginal commentaries from al-Qurṭubī's tasfir. images by Dmitry Bondarev

Collapse of the old kingdom.

Towards the end of the 14th century, dynastic conflicts emerged between the reigning sultan Dawud b. Ibrahim Nikale (r. 1366-76) and the sons of his predecessor, Idrīs, who formed rival branches of the same dynasty. This weakened the empire’s control of its outlying provinces and subjects, especially the Bulala whose armies defeated and killed Dawud and his three sucessors. The fourth, ‘Umar b. Idrīs (r. 1382-7) left the capital Njimi and abandoned Kānem. The 1391 letter by his later sucessor, sultan ʿUthmān b. Idrīs (r. 1389–1421) to the Mamluk sultan mentions that Mai ‘Umar was killed by the judhām whom he refers to as ‘polytheist arabs.’ Between 1376 and 1389, seven successive kings of Kānem fell fighting the Búlala before the latter’s rebellion was crushed by sultan ‘Uthman.40

During this period of decline the rulers of Kānem and most of their allies gradually shifted their base of power to the region of Bornu, west of lake Chad. Al-Maqrizi's account indicates that once in Bornu, the Sefuwa rulers directed their armies against the Bulala who now occupied Kānem. They would eventually recapture the former capital Njimi during the reign of Idris Katakarmabi (c 1497-1519). By this time however, the capital of the new empire of Bornu had been established at Ngazargamu by his father Mai ‘Ali Ghadji in 1472.41

In the century following the founding of Ngazargamu, Bornu reconquered most of the territories of medieval Kānem. The new empire expanded rapidly during the reign of Mai Idris Alooma (r.1564-1596) who recaptured Kawar as far north as Djado and the borders of the Fezzan. His predecessors continued the diplomatic tradition of medieval Kānem by sending embassies to Tunis and Tripoli. After the Ottoman conquest of Tripoli, Bornu sent further embassies to Tripoli in 1551, and directly to Istanbul in 1574, shortly before the Bornu chronicler Aḥmad ibn Furṭū completed his monumental work of the empire’s history titled kitāb ġazawāt Kānim (Book of the Conquests of Kanem) in 1578.42

Its in this same chronicle that the legacy of medieval Kānem was recalled by its sucessors:

“Everyone was under the authority and protection of the Mais of Kanem.

We have heard from learned Sheikhs that the utmost extent of their power in the east was to the land of Daw [Dotawo/Nubia] and to the Nile in the region called Rif; in the west their boundary reached the river called Baramusa [Niger].

Thus we have heard from our elders who have gone before. What greatness can equal their greatness, or what power equal their power, or what kingdom equal their kingdom?

None, indeed, none. . .”43

However, in the modern historiography of west Africa, the fame of medieval Kānem was overshadowed by imperial Ghana, Mali and Songhai, making Kānem the forgotten empire of the region.

Dabassa, Kawar, Niger. Tillet Thierry

My latest post on Patreon is a comprehensive collection of links to over 3,000 Books and Articles on African history, covering over five thousand years of history from across the continent.

Please subscribe to read access it here:

Medieval West Africa: Views from Arab Scholars and Merchants by Nehemia Levtzion, Jay Spaulding pg 2

The Lake Chad region as a crossroads: an archaeological and oral historical research project on early Kanem-Borno and its intra-African connections by Carlos Magnavita Zakinet Dangbet and Tchago Bouimon prg 9-10

From House Societies to States: Early Political Organisation, From Antiquity to the Middle Ages edited by Juan Carlos Moreno Garcia pg 227, Medieval West Africa: Views from Arab Scholars and Merchants by Nehemia Levtzion, Jay Spaulding pg 35-36)

From House Societies to States: Early Political Organisation, From Antiquity to the Middle Ages edited by Juan Carlos Moreno Garcia pg 220-224

From House Societies to States: Early Political Organisation, From Antiquity to the Middle Ages edited by Juan Carlos Moreno Garcia pg 224-226

Holocene Saharans: An Anthropological Perspective by Augustin Holl pg 189-191

From House Societies to States: Early Political Organisation, From Antiquity to the Middle Ages edited by Juan Carlos Moreno Garcia pg 228, Archaeological research at Tié (Kanem, Chad): excavations on Mound 1 by Carlos Magnavita and Tchago Bouimon prg 24

LA-ICP-MS analysis of glass beads from Tié (12th–14th centuries), Kanem, Chad: Evidence of trans-Sudanic exchanges by Sonja Magnavita pg 3-15

The Lake Chad region as a crossroads: an archaeological and oral historical research project on early Kanem-Borno and its intra-African connections Carlos Magnavita, Zakinet Dangbet and Tchago Bouimon prg Prg 22

Archaeological research at Tié (Kanem, Chad): excavations on Mound 1 by Carlos Magnavita and Tchago Bouimon prg 35-36

Al-Qasaba et d'autres villes de la route centrale du Sahara by Dierk Lange and Silvio Berthoud pg 22, 37

Medieval West Africa: Views from Arab Scholars and Merchants by Nehemia Levtzion, Jay Spaulding pg 44, 46

Évolutions paléoclimatique et culturelle Le massif de l’Aïr, le désert du Ténéré, la dépression du Kawar et les plateaux du Djado by Tillet Thierry

Kanem, Bornu, and the Fazzān: Notes on the political history of a Trade Route by B. G. Martin pg 19

Kanem, Bornu, and the Fazzān: Notes on the political history of a Trade Route by B. G. Martin pg 19

Medieval West Africa: Views from Arab Scholars and Merchants by Nehemia Levtzion, Jay Spaulding pg 51,

UNESCO General History of Africa Vol. 4 pg 260 n 79

Medieval West Africa: Views from Arab Scholars and Merchants by Nehemia Levtzion, Jay Spaulding pg 98

Across the Sahara: Tracks, Trade and Cross-Cultural Exchange in Libya edited by Klaus Braun, Jacqueline Passon

Darfur (Sudan) in the Age of Stone Architecture C. AD 1000-1750: Problems in Historical Reconstruction by Andrew James McGregor 22-24

The Lake Chad region as a crossroads: an archaeological and oral historical research project on early Kanem-Borno and its intra-African connections by Carlos Magnavita, Zakinet Dangbet and Tchago Bouimon prg 11-14

Holocene Saharans: An Anthropological Perspective by Augustin Holl pg 212)

Essouk - Tadmekka: An Early Islamic Trans-Saharan Market Town pg 265

Medieval West Africa: Views from Arab Scholars and Merchants by Nehemia Levtzion, Jay Spaulding pg 87-88

Medieval West Africa: Views from Arab Scholars and Merchants by Nehemia Levtzion, Jay Spaulding pg 44

The Diwan Revisited: Literacy, State Formation and the Rise of Kanuri Domination (AD 1200-1600) by Augustin Holl, Holocene Saharans: An Anthropological Perspective by Augustin Holl pg 202-208

As is the case with the 19th century Kano Chronicle and the Tarikh al-fattash, earlier claims of the Diwan's antiquity can be dismissed as groundless

Holocene Saharans: An Anthropological Perspective by Augustin Holl pg 209, UNESCO General History of Africa Vol. 4 pg 239-243, Mamluk Cairo, a Crossroads for Embassies: Studies on Diplomacy and Diplomatics edited by Frédéric Bauden, Malika Dekkiche pg 671-672

UNESCO General History of Africa Vol. 4 pg 248, Holocene Saharans: An Anthropological Perspective by Augustin Holl pg 187

Kanem, Bornu, and the Fazzān: Notes on the political history of a Trade Route by B. G. Martin pg 21, The origins and development of Zuwīla, Libyan Sahara: an archaeological and historical overview of an ancient oasis town and caravan centre by David J. Mattingly pg 35-36

UNESCO General History of Africa Vol. 4 pg 244-247)

Medieval West Africa: Views from Arab Scholars and Merchants by Nehemia Levtzion, Jay Spaulding pg 35-36, UNESCO General History of Africa Vol. 4 pg 249)

Al-Qasaba et d'autres villes de la route centrale du Sahara by Dierk Lange and Silvio Berthoud pg 32-33

Medieval West Africa: Views from Arab Scholars and Merchants by Nehemia Levtzion, Jay Spaulding pg 52, 7

Medieval West Africa: Views from Arab Scholars and Merchants by Nehemia Levtzion, Jay Spaulding pg 87-88)

Du lac Tchad à la Mecque by Rémi Dewière pg 247-248,252, Medieval West Africa: Views from Arab Scholars and Merchants by Nehemia Levtzion, Jay Spaulding pg 52,

UNESCO General History of Africa Vol. 4 pg 254, The History of Islam in Africa edited by Nehemia Levtzion, Randall L. Pouwels pg 80

Mamluk Cairo, a Crossroads for Embassies: Studies on Diplomacy and Diplomatics edited by Frédéric Bauden, Malika Dekkiche pg 661-665, Central Sudanic Arabic Scripts (Part 2): Barnāwī By Andrea Brigaglia, Multiglossia in West African manuscripts: The case of Borno, Nigeria By Dmitry Bondarev pg 137-143

Old Kanembu and Kanuri in Arabic script: Phonology through the graphic system by Dmitry Bondarev pg 109-111

The Place of Mahrams in the History of Kanem-Borno by M Aminu, A Bornu Mahram and the Pre-Tunjur rulers of Wadai by by HR PALMER

UNESCO General History of Africa Vol. 4 pg 258, 263, Medieval West Africa: Views from Arab Scholars and Merchants by Nehemia Levtzion, Jay Spaulding pg 102-106)

NESCO General History of Africa Vol. 4 256, 258-260, 265)

Mai Idris of Bornu and the Ottoman Turks by BG Martin pg 472-473, Du lac Tchad à la Mecque: Le sultanat du Borno by Rémi Dewière pg 29-30

Historians regard this passage as a reminiscence of a perceived glorious imperial past, rather than an accurate reconstruction of its exact territorial boundaries, the limits mentioned are at best being related to areas subject to raids.

Sudanese Memoirs: Being Mainly Translations of a Number of Arabic Manuscripts Relating to the Central and Western Sudan, Volume 1 by Herbert Richmond Palmer, pg 16, The Lake Chad region as a crossroads: an archaeological and oral historical research project on early Kanem-Borno and its intra-African connections by Carlos Magnavita, Zakinet Dangbet and Tchago Bouimon, pg 97-110, prg 13

Thank you for this, I hope one day someone clever enough perhaps with the use of AI , to map and recreate what those towns and cities looked like at their height, any takers? 😉

Mr Samuel (with apologies if I should have addressed you with another title!),

I have been following your substack with glee. But today, I am especially glad that you are writing about Kanem. I am in the process of writing a book on religions of the African Diaspora—and have to begin on the continent of Afrika. My point in doing so is that Africa and its many spiritualities cannot be understood when the history and the people are so maligned. I wrote of this empire and Mansa Musa, but I have time to add in some of your material, which is so rich in detail. I will be able to cite you as well—I will use your substack link as the reference point.

Thank you.

Stephanie Mitchem