A history of Horses in the southern half of Africa ca. 1498-1900.

Horses and humans have shared a long history in Africa since the emergence of equestrian societies across the continent during the bronze age.

For over 3,000 years, Horses were central to the formation and expansion of states in West Africa, the Maghreb, and the Horn of Africa, leading to the creation of some of the world's largest land empires such as Kush, Songhai, and Bornu, whose formidable cavalries extended across multiple ecological zones.

While the use of horses is often thought to have been confined to the northern half of the continent, Horses were present in parts of the southern half of the continent and equestrian traditions emerged among some of the kingdoms of southern Africa where the horse became central to the region’s political and cultural history.

This article explores the history of the Horse in the southern half of Africa, including its spread in warfare, its adoption by pre-colonial African societies, and the emergence of horse-breeds that are unique to the region.

Map showing the spread of horses in the southern half of Africa.

Horses and other pack animals in the southern half of Africa before the 17th century.

One of the earliest mentions of Horses on the mainland of southern Africa comes from a Portuguese account in 1554, describing the journey of a group of shipwrecked sailors north of the Mthatha River (Eastern Cape province). The Portuguese mention that they saw “a large herd of buffaloes, zebras, and horses, which we only saw in this place during the whole of our journey”1

This isolated reference to horses in southern Africa is rather exceptional since the rest of the earliest Portuguese accounts only mention horses in the Swahili cities of the East African coast.

Horses spread to the African continent during the second millennium BC, and were adopted by many societies across the Maghreb, West Africa, and the Horn of Africa by the early centuries of the common era. However, the spread of Horses south of the equator was restricted by trypanosomiasis, which explains the apparent absence of the Horse among the mainland societies of that region, and their use of oxen as the preferred pack animal.

Al-Masudi’s 10th-century description of Sofala (on the southern coast of Mozambique) for example, mentions that the Zanj of that region “use the ox as a beast of burden, for they have no horses, mules or camels in their land” adding that “These oxen are harnessed like a horse and run as fast.” A 12th-century account by Al-Idrisi describing the island of Mombasa in modern Kenya mentions that the King's guards “go on foot because they have no mounts: horses cannot live there.”2

While neither of these writers visited Sofala (al-Masudi may have reached Pemba), their descriptions were likely influenced by the extensive use of oxen as pack animals among many mainland societies in the southern half of the continent.

The Khoe-san speakers of south-western Africa for example are known to have used cattle in transport and in warfare.

Accounts of their first encounter with the Portuguese in 1497, mention that the oxen of the Khoe-san were “very marvellously fat, and very tame” adding that “the blacks fit the fattest of them with pack-saddles made of reeds ...and on top of these some sticks to serve as litters, and on these they ride.”3 The Khoe-san famously deployed these oxen during the battle of Table Bay in 1510. The warriors skilfully used their herd of cattle as moving shields and successfully defeated the Portuguese forces of Dom Francisco d'Almeida.4

Other societies in south-west Africa, such as the Bantu-speaking Xhosa also rode on cattle as attested in the earliest documentary record about their communities in the 17th century. Trained oxen of the Khoe-san, Xhosa, and the Sotho were ridden with saddles made of sheepskin fastened by a rope girth. They usually had a hole drilled through the cartilage of their noses and a wooden stick with a rope fastened to either end to enable the rider to direct the animal.5

Further north in the regions between modern Angola and Zambia, riding oxen were utilized by various African societies, especially in the drier savannah regions where large herds of cattle could be kept.

The 1798 account of the Portuguese governor of Mozambique-Island, Francisco José de Lacerda, mentions that riding oxen (bois cavallos) were the primary means of transport in the Lunda province of Kazembe, besides the more ubiquitous head porterage. While Lacerda recommended that the Portuguese should import camels or domesticate zebras, multiple attempts to introduce camels ended in failure, and the zebra remains undomesticated.6

Later accounts from the 19th century document the extensive use of riding oxen in Angola by both local and foreign traders traveling as far as Congo and parts of Zambia. A particular breed of cattle from Barosteland (the Lozi kingdom) called the ‘Yenges’ were used as riding oxen in Angola7. According to an account from 1875, oxen were trained for riding at Moçâmedes in southwestern Angola; “the cartilage of the nose is perforated, and through the opening, a thin, short piece of round iron is passed, at the end of which are attached the reigns and the animal is guided by them in the same manner as a horse.”8

a Sanza (thumb piano) with an equestrian figure riding a highly stylized bull, 19th century, Chokwe artist, Angola/D.R.Congo, Cleveland Museum

Horses appear more frequently in the earliest accounts of Portuguese visitors to the East African coast.

When Vasco Da Gama first arrived in the city of Malindi in 1498, he observed two horsemen engaged in a mock fight. The Portuguese thus sent gifts to the king of Malindi, which included a saddle, bridles, and stirrups, all of which the king utilized during a brief ceremony where he rode on horseback. In 1505, after the Portuguese invasion of Kilwa by Dom Francisco d’Almeida (before he was killed by the Khoe-San), the rival kings he installed also rode on horseback to proclaim their ascendancy, likely inspired by the ceremony witnessed at Malindi, or part of a pre-existing tradition.9

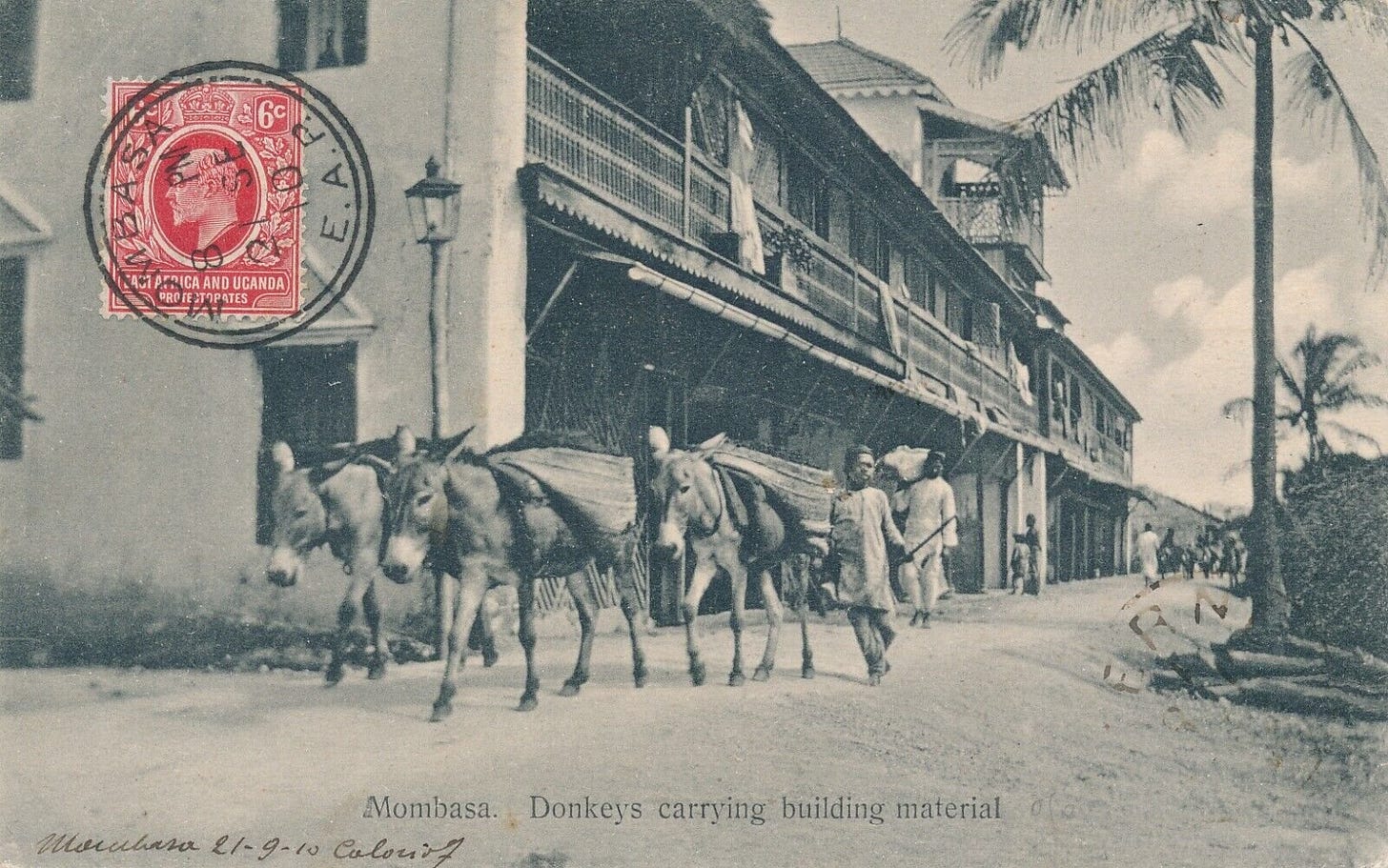

An account from 1511 by Tom Pires indicates that the horses of the East African coast were imported from Yemen. He mentions that; “Goods are brought from Kilwa, Malindi Brava, Mogadishu, and Mombassa in exchange for the good horses in this Arabia.”10 However, later accounts of Swahili trade and military systems indicate that these horses were used sparingly, likely only serving a ceremonial function, while donkeys and camels remained the main pack animals, and can still be seen in the modern streets of Lamu and Mombasa.

Donkeys carrying building material, early 20th century, Mombasa, Kenya.

The defeat of European cavalries in subequatorial Africa: Portuguese Horsemen in Angola and Zimbabwe.

The earliest encounter with European horses in the southern half of the continent began during the first wave of invasions of the mainland during the late 16th century.

In 1570-71, the Portuguese conquistador Francisco Barreto traveled up the Zambezi River at Sena (in Mozambique) with about “twenty three horses and five hundred and sixty musqueteers” in his failed invasion of the kingdom of Mutapa (in Zimbabwe), where some of the horses were poisoned by rival Swahili merchants while others died due to disease.11

Along the Atlantic coast in what is today modern Angola, a few horses were reportedly introduced in the kingdom of Kongo, along with Portuguese mercenaries to serve the Kongo king Afonso I as early as 1514, but both proved to be rather unsatisfactory, and the horses did not survive for long.12

Significant numbers of war horses only arrived in west-central Africa during the Portuguese invasion of the kingdom of Ndongo in the late 16th century which led to the creation of the coastal colony of Angola with its capital at Luanda.

In 1592, Francisco de Almeida (unrelated to the one mentioned above) arrived in Luanda with 400 soldiers and 50 horsemen who led a failed invasion into the Kisama province of Ndongo in order to reverse an earlier defeat inflicted on the Portuguese forces by Ndongo's army. The initial attack using the cavalry disorganized the armies of Kisama, although the latter countered the effect of cavalry by using the surrounding cover of the woods to draw and defeat the Portuguese force, forcing them to retreat.13

A later invasion of the kingdom of Ndongo & Matamba in 1626 led by Bento Banha Cardoso against the famous queen Njinga was relatively successful. The Portuguese installed an allied king opposed to Njinga, whose retreating forces were unsuccessfully pursued by “eighty cavalry and foot soldiers.” Cavalry frequently appeared in Portuguese battles with Njinga's army, but their numbers remained modest, with only 16 cavalry among the 400 Portuguese officers and 30,000 auxiliaries at the battle of Kavanga in 1646.14

The small cavalry force of the Portuguese was maintained by constantly importing remounts from Brazil and other places, but these troops were never a significant factor in warfare. They typically fought dismounted, as they did at Kavanga, and even in reconnaissance or pursuit never went faster than the quick-footed pedestrian scouts.15

The Portuguese who had come to central Africa hoping to repeat the feats of the Spanish horsemen in Mexico were quickly disappointed. Their early claims that one horseman was equal to a thousand infantrymen were rendered obsolete by the realities of warfare in central Africa.16 The last of the largest Portuguese invasions which included a cavalry unit of 50 horsemen was soundly defeated by the armies of Matamba in 1681; more than 100 Portuguese men were killed along with many of their 40,000 African auxiliaries.17

It should be noted that the ineffectiveness of cavalry warfare didn’t present a significant impediment to Portuguese colonization of the southern half of the continent, as they nevertheless managed to establish vast colonies in the interior of central Africa, south-east Africa, and the Swahili coast, which at their height in the early 17th century, occupied a much larger territory than the Dutch Cape colony of south-west Africa, where the environment was more conducive to horses and cavalry warfare.

From the Cape to the kingdoms of Southern Africa: the spread of an equestrian tradition to the Khoe-San, Xhosa, Tswana, Mpondo, Sotho, and Zulu societies.

Horses arrived in the Dutch Cape colony in 1653, about a century after they were first sighted in the eastern Cape region by the Portuguese.

The importation of horses, which began with four Javanese horses brought by the colony’s founder Van Riebeeck in 1653, was a perilous process and their numbers remained low for most of the 17th century. African horse-sickness initially constrained horse breeding, forcing settlers to use idiosyncratic mixtures of local knowledge of disease management. They learned from the Khoe herders how to use smoky fires to discourage flies, grazing at higher elevations, and where to move horses between seasons inorder to keep the stock alive.18

After gradually building up their stock of horses, settler authorities used them to display settler ascendancy to the subject population of the cape. By 1670, they established horse-based ‘commando’ units for policing the frontier; these traveled as cavalry but attacked as typical infantry units that dismounted to shoot. The number of Horses steadily rose from 197 in 1681 to 2,325 in 1715 to 5,749 by 1744. Horse riding and warfare became an important symbol of social identity and military power for the Boer population of the cape, which prompted neighbouring African societies to adopt this equestrian tradition.19

Beginning in the 1780s, creolized groups of Khoe-san speakers such as the Griqua and Kora, mounted on horses, moved to the Orange River area and beyond as part of the eastward migration from the Cape colony. The small Griqua and Kora societies were primarily engaged in cattle raiding and horse trade with and against sedentary communities like the Xhosa and Sotho. Griqua and Kora warriors used horses to supply mobility but primarily fought on foot.20

Other creolized groups such as the AmaTola, assimilated horses into the raiding economies, and their belief systems. They brought horses to the Drakensberg from the eastern Cape frontier and became acculturated into the neighboring sedentary societies, especially the Xhosa from whom their ethnonym is likely derived and whose equestrian tradition they initially influenced.21

Spear-wielding men [San foragers], some probably dismounted from the nearby horses, ‘hunt’ a hippopotamus. Traced by Patricia Vinnicombe from a rock-painting in the East Griqualand area of KwaZulu-Natal, South Africa.22

Korana horseman, ca. 1836, illustration by Thomas Arbousset and François Daumas.

In the modern eastern cape region, the Xhosa gradually adopted the use of horses and firearms during their century-long wars against the Boers, British and neighboring African groups. The armies Xhosa king Sarhili (r. 1835-1892) won several battles against the neighbouring Thembu and Mpondo due to their skillful use of horses and firearms. By 1846, Xhosa factions were able to mobilize as many as 7,000 armed mounted men, and they soon became excellent horsemen, although horses weren't commonly used in actual combat due to the terrain.23

In contrast to the Sarhili’s Xhosa kingdom, the neighboring kingdom of Mpondo under King Faku (r. 1818 -1867) did not create cavalry units. King Faku often preferred to avoid hostilities with the Boers and the British, and instead played the two groups against each other. The Mpondo nevertheless acquired horses from the neighbouring Khoe-san groups through trade and raiding, and the horses were used in transport and minor conflicts in Mpondoland.24

procession of men on horse-back in Pondoland, ca. 1936, eastern cape region, South Africa. British Museum.

two men riding on horse-back in Pondoland, ca. 1936, British Museum.

Raids by the Kora against the baSotho made a significant impression on the latter, whose king Moshoeshoe (r. 1822-1870) acquired his first horse in 1829 while he was consolidating his power to create the kingdom of Lesotho. Moshoeshoe's subjects quickly became more than a match for the Kora and other San groups as they acquired their own horses and guns. Some were captured from the Kora, while others were procured by individuals who had gone to work on farms in the Cape Colony, and many more were obtained through trade.25

Moshoeshoe began to build up a small cavalry as he gained more followers. He attacked the predatory bands of the Kora and Griqua from the early 1830s, and traded with some who were allies. By 1839 the price of horses had increased to ten guineas (or six oxen for one horse) at Griqua Town because there was a ready buyer’s market in the neighbouring baSotho chiefs. Between 1833 and 1838 Moshoeshoe imported 200 horses and by 1842 he had 500 armed horsemen who were “constantly prepared for war.”26

baSotho horsemen in the early 20th century, photo likely from the 1925 visit of the prince of wales.

‘A Basuto Scout’, engraving by Unbekannt, ca. 1880. ‘A Mosotho Horseman’, undated photo at the National Archives, UK. Horseman from from Basutoland, ca. 1936, Museum of Archaeology and Anthropology, UK.

Horses were used to transport mounted infantry or for cavalry action with the knobkierie and assegai (spear). By 1852 the Basotho forces stood at about 6,000, “almost all clothed in European costumes and with saddles.” These horsemen managed to put up a successful defense against a British colonial army at the Battle of Berea.27

Increased conflicts between the kingdom and the Boer Orange Free State culminated in the first First Basotho–Boer War in 1858, and a second war in 1868, which involved between 10,000 and 20,000 Basotho cavalry and infantrymen. Losses from both conflicts compelled Moshoeshoe to seek British protection in 1869, and Lesotho became part of the Cape colony by the time of his death in 1870.28

Internally, the kingdom mostly remained under local authority, and horses continued to play a central role in its political administration and cultural traditions. Horses facilitated the governance of greater areas and provided a more effective communication system. The Horse population of the kingdom doubled from just under 40,000 in 1875 to over 80,000 in 1890 compared to a human population of about 120,000. Horses played a key role in the 1880-81 'Gun-war' against the Cape colony's attempt to disarm the baSotho, which ended with the latter retaining their guns and horses, even as their kingdom was placed directly under British in 1884.29

Horsemen in the Quthing District of Basutoland, ca. 1936, British Museum.

Further north in the modern province of Kwazulu Natal, the arrival of Horses is associated with the rise of the AmaThethwa king Dingiswayo, who reportedly traveled to the eastern cape region and returned on horseback with a firearm30. However, horses would not be widely adopted in the military systems of the Mthethwa and Zulu kingdoms, with the late exception of the Zulu king Dinuzulu (r. 1884-1913) who included a small contingent of 30 horsemen to assist his infantry force of 4,000 during the rebellion of 1888.31

Horses arrived late in the northmost provinces and were less decisive in warfare. In June 1831 a coalition of 300 Griqua horsemen and several hundred Tswana spearmen was roundly defeated by the Ndebele king Mzilikazi near present-day Sun City in the north-west province. The Ndebele captured large numbers of firearms and horses but did not make much use of them and most of the captured horses eventually died of disease.32

The mixed infantry and cavalry forces of the Boers fared better against the armies of the Ndebele and the Zulu between 1836-1838, and against the horse-riding Tswana chiefdoms of Gasebonwe and Mahura in 1858. However, horses were rarely used in actual combat and horse-sickness restricted the length of some campaigns, such as in the wars with the baPedi ruler Sekhukhune in 1878. In these regions, both the Boers and the British used horses to transport troops to battle; in skirmishes to break enemy formations; and to pursue defeated foes.33

These tactics were then applied to devastating effect during the second Anglo-Boer war of 1899-1902, which was the last major cavalry war in southern Africa, resulting in the deaths of at least 326,000 horses alongside nearly 200,000 human casualties.34

Horse Breeding and Trade

The vast majority of horses in the pre-colonial societies of southern Africa originated from the ‘Cape Horse’ breed, which measured about 14.3 hands. The ‘Cape Horse’ was itself the result of a globalised fusion of the following breeds; the South-east Asian or ‘Javanese’ pony (itself arguably of Arab–Persian stock); imported Persians (1689); South American stock (1778); North American stock (1792); English Thoroughbreds (1792); and later Spanish Barbs (1807); with a particularly significant Arabian genetic influence.35

The export of horses from the Cape colony began in 1769 but this trade remained very modest and erratic save for between 1857 and 1861 when thousands of Horses were exported to India. The Horse trade with neighboring African societies (often clandestine) was more significant, especially after the British conquest of the cape in 1806 which compelled some of its population to migrate beyond its borders.

Despite the recurring epidemic of horse-disease which killed anywhere between 20-30% of the horse population every two decades, the number of Horses in the cape exploded from 47,436 at the time of the British conquest to 145,000 in 1855 to 446,000 in 1899 on the eve of the Anglo-Boer war. However, this was largely the result of increased imports, as most of the remaining Cape Horses were killed by disease and in the Anglo-Boer war. By the end of the 19th century, the once redoubtable Cape horse was pronounced as being as ‘extinct as the quagga’, having been replaced by the English Thoroughbred.36

The Kora, Griqua, Xhosa, and Sotho, began breeding horses as soon as they were acquired. By the early 19th century, the Griqua established a settlement in Philippolis, and were becoming increasingly equestrianised and ‘breeding good horses.’37 As late as 1908, a colonial report notes that “in the fine territory of East Griqualand” (just south of Lesotho), “the principal industries are sheep farming, horse breeding and agriculture on a small scale, horse sickness, which is so destructive in many parts of Cape Colony, being unknown.”38

Trade between the British-controlled Cape colony and the Xhosa in the 1820s ensured that horses and guns were acquired by the latter, albeit illegally as it was forbidden. The Xhosa later started breeding horses themselves and by the end of the 1830s, one cape official noted: “Not many years ago the Africans … looked upon a horse as a strange animal which few of them would venture to mount. Now they are becoming bold horsemen, are possessed of large numbers of horses.”39

In Lesotho, a local horse breed known as the ‘Basuto pony’ which measures about 13.2-14.2 hands40, was created from a heterogeneous stock acquired from various sources, whose diverse origins are reflected in the breed’s changing nomenclature. The earliest Sesotho phrase for the horse was khomo-ea-haka, literally translated as ‘cattle called haka’ (hacqua being the Khoisan name for a horse). Haka was then replaced by the word ‘pere’ from the Dutch/Afrikaans ‘perd’ likely obtained from the Kora. From 1830 to 1850 imported stock was mostly ‘Cape horses’ of ‘South-east Asian’ origin, that were later mixed with the English Thoroughbred horses in the second half of the 19th century.41

a Basuto pony, oil on canvas painting by William Josiah Redworth, ca. 1904.

By the early 1870s, Basutoland was a major supplier of grain and horses to the Kimberly diamond fields, rivaling the Boer Free State Boers. This export trade grew rapidly on the outbreak of the Anglo-Boer wars in 1899, as the baSotho sold their horses to both sides and dictated the terms of the market. In 1900 alone the Basotho exported 4,419 horses worth £64,031 (£6,087,000 today). Basotho ponies were particularly desired, because they were famously hardy and were already acclimatized to local conditions and diseases. Their quality was praised by the imperial authorities and British press: “They are all very square-built active animals, just the thing for campaigning, but the Basutos would not sell their own riding horses for love or money. All they would sell were the spare horses.”42

As late as 1923, the “principal occupations” of Lesotho were “agriculture, horse-breeding and stock-farming” according to a detailed account of the kingdom whose author also praises the Basuto pony, describing it as a ‘fine beast’ that will “carry his rider in safety along the most precipitous paths in the rugged mountains amongst which he has been bred.”43

In the north-western region of South Africa bordering Namibia and Botswana, a type of horse breed similar to the Basuto Pony was developed and was referred to as the Namaqua pony, named after the Nama-speaking Khoe-san groups of the region. The Namaqua pony was spread to Botswana and Namibia where it was mixed with German horse breeds, although it is said to be currently extinct.44

Basotho Pony, ca. 1902, Harold Sessions.

The Horse in the cultural history of pre-colonial Southern Africa.

Among the Khoe-san speaking groups like the Korana and AmaTola, horse-riding became central to social identity and the economies of their frontier societies.45 This is best reflected in the surviving artwork of both groups, which often includes stylized depictions of human figures on horseback, alongside other animals associated with local belief systems such as baboons. The motif of the horse and baboon was harnessed by shamans who assumed their protective power to keep the AmaTola safe on their mounted forays.46

The emphasis on horses in their art reflects the value that these animals had as one of the chief means by which desirable goods could be obtained, traded, and defended. Riders are frequently shown controlling their steeds using reins and sometimes have a thin horizontal line emanating from their shoulders, likely depicting a gun, and in one artwork riders are shown close to an elephant, likely signaling the importance that hunting ivory had for Korana, Griqua, and other frontier groups.47

Human figure with a baboon head and tail dances with dancing sticks while horsemen exhibiting mixed material culture (brimmed hats with feathers, spears, muskets) ride together. Rock art from the headwaters of the Mankazana River in the Eastern Cape region, Image by Sam Challis and Brent Sinclair-Thomson.48

In Lesotho, the military horse was seamlessly incorporated into male domestic life. According to an account from 1875: “the traditional wish with every young Basuto to possess a horse and gun, without which he does not consider himself "a man", and is liable to be jeered at by his more fortunate fellows.”49

The longevity of this militarised masculinity is illustrated by the oral testimony of an old man, born in 1896, who spoke of riding a horse and bearing arms in the early decades of the twentieth century even when it was not strictly speaking necessary, simply to exhibit a permanent preparedness for war.50

Group of horseriders in Lesotho, ca. 1936, British Museum.

While cattle remained the main symbols of wealth, horses could be used in social transactions like bohali (bridewealth). Men usually received their first horse from their fathers which could be given as part of bohali, especially the ‘Molisana’ horse. By the end of the 19th century, virtually every male adult in Lesotho had a horse.

Horse riding among baSotho women was relatively rare. According to a late account from 1923, “The women ride seldom, but young herds (youths) ride anything and everything that can boast four legs, from a goat to a bullock, tumbling off and then on again till the unhappy animal gives in and becomes quite a respectable mount.” In contrast, elite women in Mpondoland typically rode horses.51

Beyond their military function, horses were also used in domestic contexts, not just in rural transport, but also in various activities including; hunting (typically among the San foragers but also among the Boers and the African groups); in ploughing and threshing (complementing oxen for the Boers and the Sotho); and in the transport of trade goods (everything from horse-drawn cabs of the 19th-century cape colony, to the simple loading of goods on horseback in the rest of the country).52

Horsewomen in Lesotho and Pondoland, ca. 1936, South Africa, British Museum.

‘Basuto ponies threshing grain’ ca. 1924, by E. A. T. Dutton.

Transporting goods on horseback in Pondoland, ca. 1936, British Museum.

Horse riding and breeding went into rapid decline during the post-war period in South Africa. Despite multiple attempts to revive the use of horses during the 1920s and 40s, horses were increasingly becoming obsolete on large-scale commercial farms, in public transport, and in the military, the few remaining uses of horses became symbolic, and their breeding became intertwined with the emerging politics of the apartheid era.53

In Lesotho, Horses retained their significance in the local economy and are still widely used for general transport over the dramatic topography of the country. The Horse remains an important symbol of Sotho cultural identity and appears in the Basotho coat of arms. The cultural significance of the Horse in Lesotho and the survival of the ‘Basuto pony’ to the present day makes the country one of the most remarkable equestrian societies on the continent.

Horsemen in Lesotho, photo by Lefty Shivambu/Gallo Images.

In the 17th century, cloth exports from the eastern province of the Kongo Kingdom rivaled some of the most productive textile industries of Europe. Most of this cloth was derived from further inland in the great Textile Belt of Central Africa;

Please subscribe to read about the history of the cloth trade in the ‘Central African Textile Belt’ here;

Records of South-Eastern Africa: Collected in Various Libraries, Volume 1, edited by George McCall Theal pg 258

The East African Coast: Select Documents from the First to the Earlier Nineteenth Century by Stewart Parker Freeman-Grenville pg 15-16, 20

The Cape Herders: A History of the Khoikhoi of Southern Africa by Emile Boonzaier pg 55)

Remembering the Khoikhoi victory over Dom Francisco de Almeida at the Cape in 1510 by David Johnson

Riding High: Horses, Humans and History in South Africa by Sandra Scott Swart pg 20)

Lacerda's Journey to Cazembe in 1798 pg 19-20, A Short History of Modern Angola by David Birmingham pg 30-32

The Use of Oxen as Pack and Riding Animals in Africa By Gerhard Lindblom pg 45-49

Angola and the River Congo, Volume 2 By Joachim John Monteiro pg 218-219

The East African Coast: Select Documents from the First to the Earlier Nineteenth Century by Stewart Parker Freeman-Grenville pg 54, 62-63, 95, 107

The East African Coast: Select Documents from the First to the Earlier Nineteenth Century by Stewart Parker Freeman-Grenville pg 125

Records of South-Eastern Africa: Collected in Various Libraries, Volume 1 edited by George McCall Theal pg 26, A History of Mozambique by M. Newitt pg 57-58

Warfare in Atlantic Africa, 1500-1800 By John Kelly Thornton pg 108

Njinga of Angola: Africa’s Warrior Queen By Linda M. Heywood pg 28, A History of West Central Africa to 1850 By John K. Thornton pg 101

Njinga of Angola: Africa’s Warrior Queen By Linda M. Heywood pg 87, 101, 104, 106, 144, 146

The Art of War in Angola, 1575-1680 by John Kelly Thornton pg 367, 375)

The Art of War in Angola, 1575-1680 by John Kelly Thornton pg 375

the Mbundu and their neighbours under the influence of the Portuguese 1483-1700 by D Birmingham pg 231-232

Riding High: Horses, Humans and History in South Africa by Sandra Scott Swart pg 22-24

Riding High: Horses, Humans and History in South Africa by Sandra Scott Swart pg 27-31

Riding High: Horses, Humans and History in South Africa by Sandra Scott Swart pg 81-82, A Military History of South Africa: From the Dutch-Khoi Wars to the End of Apartheid by Timothy J. Stapleton pg 15-18

The Impact of the Horse on the AmaTola 'Bushmen'” New Identity in the Maloti-Drakensberg Mountains of Southern Africa by W Challis pg 21, 121-131.

Horse Nations: The Worldwide Impact of the Horse on Indigenous Societies Post-1492 by Peter Mitchell pg xxxi

The House of Phalo: A History of the Xhosa People in the Days of Their Independence by Jeffrey B. Peires pg 116-117, 155-156, Riding High: Horses, Humans and History in South Africa by Sandra Scott Swart pg 79

Faku: Rulership and Colonialism in the Mpondo Kingdom (c. 1780-1867) By Timothy J. Stapleton pg 125-127, 77, 82, 99, 102, 112-119.

Sotho Arms and Ammunition in the Nineteenth century by A Atmore pg 536-537, Interaction between South-Eastern San and Southern Nguni and Sotho Communities c.1400 to c.1880 by Pieter Jolly pg 47, 51

Riding High: Horses, Humans and History in South Africa by Sandra Scott Swart pg 83-84)

A Military History of South Africa: From the Dutch-Khoi Wars to the End of Apartheid by Timothy J. Stapleton pg 39-40, Riding High: Horses, Humans and History in South Africa by Sandra Scott Swart pg 87)

A Military History of South Africa: From the Dutch-Khoi Wars to the End of Apartheid by Timothy J. Stapleton pg 41-46)

Riding High: Horses, Humans and History in South Africa by Sandra Scott Swart pg 84, 88-91, 94)

Kingdoms and Chiefdoms of Southeastern Africa By Elizabeth A. Eldredge pg 167-170

A Military History of South Africa: From the Dutch-Khoi Wars to the End of Apartheid by Timothy J. Stapleton pg 108)

A Military History of South Africa: From the Dutch-Khoi Wars to the End of Apartheid by Timothy J. Stapleton pg 19-20)

A Military History of South Africa: From the Dutch-Khoi Wars to the End of Apartheid by Timothy J. Stapleton pg 27-30, 49,55-56, 66-69)

Riding High: Horses, Humans and History in South Africa by Sandra Scott Swart pg 104)

Riding High: Horses, Humans and History in South Africa by Sandra Scott Swart pg 32-33, The Arabian Horse and Its Influence in South Africa by Charmaine Grobbelaar.

Riding High: Horses, Humans and History in South Africa by Sandra Scott Swart pg 44, 68-75

Riding High: Horses, Humans and History in South Africa by Sandra Scott Swart pg 81)

Handbook No. 11, South African Colonies, Transvaal Hanbook with Map, edited by Walter Paton, Emigrants' Information Office, July 1908.

Riding High: Horses, Humans and History in South Africa by Sandra Scott Swart pg 43-44)

The basuto of Basutoland by Eric Aldhelm Torlough Dutton pg 65, Riding High: Horses, Humans and History in South Africa by Sandra Scott Swart pg 87

Riding High: Horses, Humans and History in South Africa by Sandra Scott Swart pg 85)

Riding High: Horses, Humans and History in South Africa by Sandra Scott Swart pg 93, 96)

The basuto of Basutoland by Eric Aldhelm Torlough Dutton pg 65

The Indigenous Livestock of Eastern and Southern Africa by Ian Lauder Mason, John Patrick Maule pg 13.

The Impact of Contact and Colonization on Indigenous Worldviews, Rock Art, and the History of Southern Africa “The Disconnect” by Sam Challis and Brent Sinclair-Thomson pg 101-104, Cattle, Sheep and Horses: A Review of Domestic Animals in the Rock Art of Southern Africa by A. H. Manhire et al. pg 27)

The Impact of the Horse on the AmaTola 'Bushmen'” New Identity in the Maloti-Drakensberg Mountains of Southern Africa by W Challis

Horse Nations: The Worldwide Impact of the Horse on Indigenous Societies Post-1492 by Peter Mitchell pg 306-307

The Impact of Contact and Colonization on Indigenous Worldviews, Rock Art, and the History of Southern Africa “The Disconnect” by Sam Challis and Brent Sinclair-Thomson pg 104

Sotho Arms and Ammunition in the Nineteenth Century by Anthony Atmore and Peter Sanders pg 541

Riding High: Horses, Humans and History in South Africa by Sandra Scott Swart pg 84, 92)

The basuto of Basutoland by Eric Aldhelm Torlough Dutton pg 73, Riding High: Horses, Humans and History in South Africa by Sandra Scott Swart pg 93-94, 159)

Riding High: Horses, Humans and History in South Africa by Sandra Scott Swart pg 42, 62 143,

Riding High: Horses, Humans and History in South Africa by Sandra Scott Swart pg 164-170

Will you be writing more about 20th Century cavalry and horse mounted military units? My time in Africa and my study of the different conflicts in Southern Africa led me to think of much of the mid-continent as tetse fly country. In the independent Congo/Zaire, there was a mounted ceremonial unit of the army (based on a Belgian Army unit) that wore a European style uniform in the colors of Mobutu’s MPR party, carrying lances and topped with large “bearskin” headgear. The unit was apparently supported in part by the local “riding club” that helped train horses and riders and provided stabling.