A history of the Buganda kingdom.

government in central Africa.

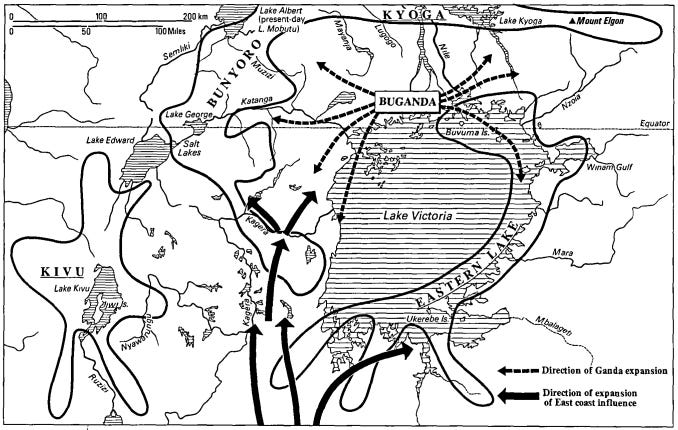

The land sheltered between the great lakes of east Africa was home to some of the continent's most dynamic kingdoms. Around five centuries ago, the kingdom of Buganda emerged along the northern shores of lake Victoria, growing into one of the region's most dominant political and cultural powers.

Buganda was a cosmopolitan kingdom whose political influence extended across much of the region and left a profound legacy in east Africa. Its armies campaigned as far as Rwanda, its commercial reach extended to the Nyamwezi heartland of western Tanzania, and its diplomats travelled to Zanzibar on the Swahili coast

This article explores the history of the Buganda kingdom from the 16th century to 1900.

Map of the Great lakes kingdoms in the late 19th century1

Support African History Extra by becoming a member of our Patreon community, subscribe here to read more on African history and to keep this blog free for all:

Background to the emergence of Buganda: Neolithic cultures and incipient states in the lakes region.

The lakes region of east Africa is a historical and cultural area characterized by shared patterns of precolonial political organization. The initial Neolithic iron-age cultures that emerged across the region from the 1st millennium BC to the middle of the 1st millennium AD, gradually declined before more complex societies re-emerged in early 2nd millennium the what is now western Uganda, at the proto-capitals of Ntusi and Bigo. Its these early societies of agro-pastoral communities that produced a shared cultural milieu in which lineage groups and incipient states would rise.2

Prior to the founding of Buganda, the region in which the kingdom would later emerge was originally controlled by of several dozen clans (bakata), a broad social institution within which were sub-clans and lineage groups. These exogamous groups were common across the lakes region, and transcended both ethnic and political boundaries of the later kingdoms. They likely represented an older form of social complexity within which were numerous small states that would be significantly transformed as the kingdoms became larger and more centralized.3

The core region of Buganda (in Busiro and Kyaddondo) was a land teaming with shrines (masabo), enclosures invested with numinous authority that contained relics of older rulers who were gradually deified and local deities who became influential in the early state. A number of these predated the foundation of the state, and some (on Buddo hill in Busiro) were sacred enough to become grounds for installation of new kings beginning in the 18th century, and would remain under the control of ritual officiants and shrine priests after the kingdom's founding.4 However, not all deities were historical personalities, nor were all important historical personalities deified, and some among both groups were shared with other kingdoms.5

Location of Busiro in relation to the iron-age sites

The kingdom's legendary founder Kintu and his descendant Kimera are credited with the introduction of several cultural and political institutions to the region that became Buganda, and the creation of the civilization/state itself. various versions of this origin myth exist, combining mythical and historical figures, and collapsing centuries long events into complex stories and geneologies. They contain salient information on the early states of the region that became Buganda, and their relationship to neighboring states particulary Bunyoro where Kimera supposedly resided for some time.6

While the legendary personalities are wholly mythical, they are representations of particular aspects of kingship as well as political and cultural changes that occurred in the early state, which facilitated their transmission into mythology. Arguably the most recognizable information relates to Kimera’s introduction into Buganda of several elements in the early state's political institutions, regalia and titlelature from Bunyoro7. Its evident that the royal genealogists who preserved these faint memories of the early state to add to the better known history of later kings, relied on the great stock of known potencies in the land represented by the numerous shrines, deities, and cultural heroes, some of which also appear in traditions of neighboring states.8

The early state in Buganda from the 16th-17th century

For most of Buganda’s early history, the power of the King (kabaka) was still curbed by the clan-heads, who controlled the political make-up of the nascent kingdom.9 The most notable ruler during this period was Nakibinge, a 16th century king whose reign was beset by rebellion and ended with his defeat at the hands of Bunyoro. The 16th to 17th century was a period of Bunyoro hegemony. The traditions of Rwanda, Nkore, Karagwe and Ihangiro all recall devastating invasions which were repelled by kings who took the title of 'Nyoro-slayer'. In Buganda, the era of Bunyoro's suzeranity is represented by the traditions on postulated defeat of Nakibinge, all of which collapse a complex period of warfare in which Buganda freed itself of Bunyoro's suzeranity.10

From the late 17th century to the mid-18th century, the kingdom built up a position of significant economic and military strength, facilitated by an efficient and centralized socio-political structure. The 17th century kings Kimbugwe and Kateregga would undertake a few campaigns beyond the core of the early state, while their 18th century sucessors Mutebi and Mawanda raised large armies and subsumed several rival states11. Mwanda in particular in credited with creating the offices of the batongole (royally appointed chiefs) thus centralizing power under the King and away from the clans.12

Expansion of Buganda from the 17th-19th century. Map by Henri Médard and Jonathon L. Earle

Buganda as a regional power in the 18th-19th century

King Mawanda (d. 1740) presided over the advance of the eastern frontier towards the Nile upto Kyagwe, an important center of trade. Mawanda also campaigned south, bringing his armies into Bundu and Kooki: a rich iron producing region on the south-western shores of lake Victoria that was home to a powerful chiefdom within Bunyoro’s orbit. Unlike its western neighbors, Buganda didn't posses significant iron deposits within its core provinces. raw iron was thus brought from outlying provinces, to be reworked and smelted across the kingdom. Mawanda's sucessor, Junju, completed the annexation of Buddu following a lengthy war. Buddu was renowned for its production of iron and high quality barkcloth, and its acquisition opened up access to a thriving industry. Junju armies also campaigned as far as the kingdom of Kiziba (in north-western Tanzania) but was forced to withdraw his overextended armies.13

Junju's sucessor Semakokiro (r. ca. 1790-1810) consolidated the gains of his predecessors, and defended the kingdom against the resurgent Bunyoro whose armies were regaining lost ground in the west. A major rebellion led by Kakungulu, who was one of Semakokiro's sons that had fled to Bunyoro, nearly reached the capital before it was repulsed. Further eastern campaigns to Bulondoganyi at the border of the Bugerere chiefdom near the Nile river were abandoned, as the kingdom's rapid expansion momentarily came to a halt.14

Semakokiro was suceeded by Kamanya (1810-1832) who resumed the expansionist campaigns of his predecessors by advancing his armies east beyond the Nile to the kingdom of Busoga, to the north as Buruuli (near lake Kyoga) and as far west as Busongora, a polity near the Rwenzori mountains that was a dependency of Bunyoro. In retaliation, Bunyoro sent the rebellious prince Kakungulu whose armies raided deep into Buganda's territory including the region around Bulondoganyi. Buganda's initial invasion of Busoga was defeated but another campaign was more sucessful, with Busoga acknowledging Buganda's suzeranity albeit only nominally. The campaigns against Buruuli which involved the use of war canoes, carried overland from lake Victoria, established Buganda's northernmost frontier.15

Kamanya was suceeded by Ssuuna (1832-1856) who consolidated the territorial gains of his predecessors while engaging in a few campaigns beyond the frontiers. Suuna campaigned southwards to the Kagera river, and his navies attacked the islands of Sesse in lake Victoria just prior to the arrival of foreign merchants in Buganda.16 In 1844, a carravan of Swahili and Arab traders from the east African coast arrived at the capital of Buganda. Snay bin Amir, the head of the carravan was hospitably received by Ssuuna and he would return in 1852, being the first of many foreign traders, explorers, missionaries that would be integrated into Buganda’s cosmopolitan society.17

Expansionist wars of Buganda and direction of foreign arrivals, Map by D. cohen

The government in 19th century Buganda : state and economy.

At the highest level of authority in Buganda was the Kabaka whose influence over the government had grown considerably in the 19th century, although his personal authority was more apparent than real. Just below the Kabaka was a large and complex bureaucracy of appointed and hereditary officials (abakungu), ministers, chiefs, clan heads and other titleholders, the most powerful among who were the Katikkiro (vizier/prime-minister) the Kimbugwe, and the Nnamasole (Queen-Mother), all of whom oversaw the judicial and taxing functions of the state and formed the innermost council within several concentric circles of power radiating from the capital.18 They resided in the transient royal capital at Rubaga (and later at Mengo), a large agglomeration with more than 20,000 residents in the mid-19th century, that was the center of political decision making where public audiences were held, official delegations were hosted and trade was regulated.19

Rubaga, the new capital of the Emperor Mtesa, ca. 1875.

The kingdom was divided into ten ssaza (provinces/counties), each under an appointed chief (abamasaza), the four most important of which were Buddu, Ssingo, Bulemeezi and Kyaggwe. which inturn had several subdivisions (gombolola)20 The military was led by Sakibobo (commander-in-chief) who was often chosen by the king. Regions within the ssaza system were the basic units of the army, with each chief providing military levies for the kingdom's army. The King had his own standing army at the capital that was likely present since the kingdom's foundation, and would eventually grow into the elite corps of royal riflemen (ekitongole ekijaasi) that was garrisoned in provincial capitals across the kingdom.21

Below these were the provincial chiefs were lower ranking titleholders and the common subjects/peasants (bakopi) who were mostly comprised of freeborn baGanda as well as a minority of acculturated immigrants and former captives. Freeborn baGanda were not serfs and they could attach themselves to any superior they chose.22 The Taxes, tributes and tolls collected from the different provinces were determined by local resources. The collection of taxes was undertaken by the hierachical network of officials, all of whom shared a percentage of the levied tribute before it was remitted to the center. Taxes were paid in the form of cowrie shells, barkcloth, trade items, and agricultural produce, with the ultimate tax burden being moderated by the mobility of the peasantry.23

Map of Buganda counties, in the early 20th century.

Corvee labour for public works was organized on a local basis from provincial chiefs, to be employed in the construction and maintenance of the kingdom's extensive road network, the enclosures and residences in the royal palaces, and the Kabaka's lake. The road network of Buganda appears in the earliest description of the kingdom.

In 1862, the explorer J. Speke observed that they were found “everywhere” and were "as broad as our coach-roads". In 1875, Stanley estimated the great highway leading to the capital as measuring 150ft, adding that in the capital were the "Royal Quarters, around which ran several palisades and circular courts, between which and the city was a circular road, ranging from 100 to 200 feet in width, from which radiated six or seven magnificent avenues". Later accounts describe the remarkably straight and broad highways bounded by trees, crossing over rivers with bridges of interlaced palm logs, in a complex network that connected distant towns and villages to the capital. They were as much an expression of grandeur as a means of communication.24

The mainstay of Buganda’s economy was agriculture, and its location on the fertile shores of lake victoria had given it a unique demographic advantage over most of the neighboring kingdoms. describing a typical estate in 1875, the explorer H.M. Stanley observed that “In it grow large sweet potatoes, yams, green peas, kidney beans, field beans, vetches, and tomatoes. The garden is bordered by castor-oil, manioc, coffee, and tobacco plants. On either side are small patches of millets, sesamum, and sugar-cane. Behind the house and courts, and enfolding them, are the more extensive banana and plantain plantations and grain crops. Interspersed among the bananas are the umbrageous fig trees".25

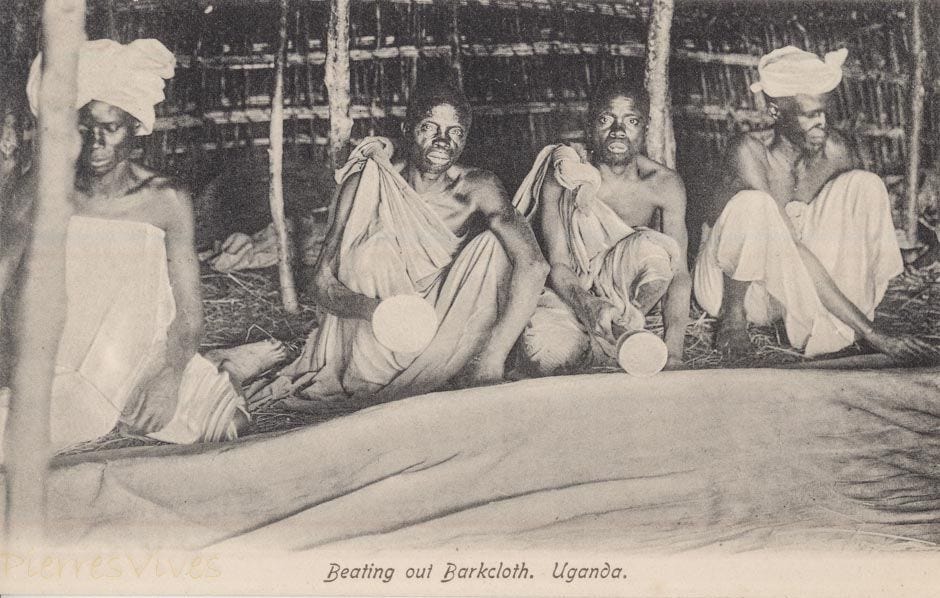

The manufacture of barkcloth was the most significant craft industry in Buganda. The cloth was derived from the barks of various kinds of fig trees, which were stripped and made flexible using a mallet in a process that took several days. They were then dyed with red and black colorants, patterned and decorated with grooves which made it resemble corduroy textiles. Barkcloth was used as clothing, beddings, packaging, burial shrouds, and wall carpets. It formed the bulk of the kingdom's exports to regional markets in Bunyoro, Nkore and as far as Nywamwezi, and remained popular well into the 1900s despite the increased importation (and later local manufacture) of cotton textiles.26

Barkcloth with geometrical patterns stencilled in black, ca. 1930, British museum

Bark cloth with star patterns, inventoried 1904, Bristol museum

Beating out barkcloth, Uganda, ca. 1906-1911, university of Cambridge.

Smithing of iron, copper and brass also constituted a significant industry. Unworked iron bought from the frontier was smelted and reworked into implements, jewelry and weapons that were sold in local markets and regionally to neighboring kingdoms. As early as the 1860s, professional smiths attached to the court were making ammunition for imported firearms, and by 1892, a contemporary account observed that local gun-smiths "will construct you a new stock to a rifle which you will hardly detect from that made by a London gun-maker".27

Leatherworking and tanning was an important industry and employed significant numbers of subjects. An account from 1874 describes the tanning of leather by the bakopi who made large sheets of leather than were "beautifully tanned and sewed together". A resident missionary in 1879 reported purchasing dyed leather skins cut in the shape of a hat. Cowhides were fashioned into sandals worn by the elite and priests since before the 18th century, with buffalo hides specifically worn by chiefs and the elite.28

The main markets in the capital was under the supervision of an appointed officer, who was in charge of collecting taxes in the form of cowrie shells, and oversaw the activities of foreign merchants. Trading centers outside the capital such as Kyagwe, Bagegere, Bale, Nsonga and Masaka were controlled by provincial chiefs, and were sites of significant domestic and export trade by ganda merchants.29 tobacco and cattle were imported from Nkore, in exchange for Bark cloth, while iron weapons, salt and captives were brought from Bunyoro in exchange for cloth (both cotton and barkcloth), copper, brass and glass beads, the latter coming from coastal traders.30

Soon after the arrival of coastal traders, Sunna constructed a flotilla of watercraft similar in shape to the Swahili mtepe ship intended to facilitate direct trade with the port town of Kageyi, which was ultimately linked to the town of Ujiji and the coastal cities.31 In the 1870s and 1880s, the enormous canoes of Buganda measuring 80ft long and 7 ft wide with a capacity to carry 50 people along with their goods and pack animals (or 100 soldiers alone), featured prominently in the organization of long-distance commerce and warfare, rendering the overland routes marginal in external trade.32 Most external trade consisted of ivory exports, whose demand was readily met by the established customs of professional hunting guilds, who often traversed the kingdom's frontiers to procure elephant tusks.33

"Mtesa, the Emperor of Uganda, Prime Minister, and Chiefs" ca. 1875. The king and his officials are dressed in the distinctive swahili kanzus and hats purchased from coastal merchants.

Buganda in the second half of the 19th century: from hegemony to decline.

In Buganda, coastal traders, missionaries and other foreign travelers found a complex courtly life in which new technologies were welcomed, new ideas were vigorously debated and alliances with foreign powers were sought where they were deemed to further the strength of the kingdom. Ssuuna’s sucessor Mutesa (r. 1856-1884) was a shrewd monarch who readily adopted aspects of coastal culture that he deemed useful, including integrating Swahili technicians into Buganda’s institutions, adopting Islam and transforming some of political institutions of the state into a Muslim kingdom. He acquired the sufficient diplomatic tools (such as Arabic literacy) that enabled him to initiate contacts with foreign states including Zanzibar (where the traders came from) and Anglo-Egyptian Sudan (which was threatening to invade Buganda and Bunyoro from the north)34

During the 1850s, Mutesa’s predecessor was reportedly in the habit of sending armed escorts to the southern kingdom of Karagwe when they heard that coastal traders wished to visit them. By 1875, Muteesa had taken his diplomatic initiative further to Sudan, ostensibly sending his emissaries to the Anglo-Egyptian capital of Khartoum for an alliance against Bunyoro. In 1869 and 1872, Mutesa sent caravans to Zanzibar, and by late 1878 a band of 'Mutesa's soldiers was reported to be returning from a mission to Zanzibar itself.35 The apparently friendly envoys sent to Khartoum were infact spies dispatched to report on the strength and movements of the enemy. Mutesa had an acute appreciation of the role which diplomacy could play in protecting Buganda's independence, and the king shrewdly confined the Anglo-Egyptian delegation at his capital, blunting the planned invasion of Bunyoro and Buganda.36

However, Mutesa registered less military success than his predecessors. Several wars against Bunyoro, Busoga, Buruli, and Bukedi during the 1860s and 1870s often ended with Buganda's defeat. Between 1870-1871, Mutesa sucessfully intervened in Bunyoro's sucession crisis with the installation of Kabarega, placed a puppet on the breakaway state of Tooro and in the Bunyoro dependency of Busongora but all were quickly lost when Kabarega resumed war with Buganda, Toro’s alliance was unreliable and Busongora expelled ganda armies.37 Mutesa also lost soldiers in aiding Karagwe's king Rumanika in quelling a rebellion. A massive naval campaign with nearly 10,000 soldiers on 300 war-canoes was launched against the islands of Buvuma in 1875/7 ended with a pyrrhic victory for Buganda, which suffered several causalities but managed to reduce the island chiefdom to tributary status. In the late 1870s, Buganda mounted a major expedition south against the Nyiginya kingdom of Rwanda but the overextended armies were defeated38.

Naval battle between the waGanda and waVuma, ca. 1875

While Mutesa had sucessfully played off the foreign influences to Buganda's advantage the situation became more volatile with the arrival of the Anglican missionaries in 1877, who were quickly followed by the French Catholics in 1879, much to the dismay of the former. As all sects were adopted by different elites and commoners across Buganda, the structures of the kingdom's institutions were complicated by the presence of competing groups. Near the end of his reign , Mutesa increasingly relied on the royal women who played a crucial role at court especially the queen-mother whose power in the land at least equal to her son.39

Mutesa was suceeded by Mwanga in 1884, who inaugurated a less austere form of government than his predecessors in response to the growing internal and foreign threats which the kingdom faced. Internal campaigning and plundering increasingly took the place of legitimate collection of tribute, as Mwanga undertook expeditions within the kingdom intended to arbitrarily seize tribute. Besides his shifting policies with regards to the presence of Christian factions at the court, the king begun an ambitious project of creating a royal lake, which required significantly more covee labour than was traditionally accepted. A combination of military losses in Bunyoro in 1887, religious factionalism, and excessive taxation that were borne by both elites and commoners ultimately ended with the brief overthrow of Mwanga in 1888.40

‘The Battle Against the Mohammedans’, 1891, illustration depicting one of the political religious wars that were fought in this period

The years 1888–93 were a tumultuous period in the history of Buganda during which two kings briefly suceeded Mwanga in 1889 before he returned to the throne in the same year. The beleaguered king had pragmatically chosen to rely on British support represented by Lord Lugard, agreeing to the former’s suzeranity over Buganda. While the Anglo-Buganda alliance proved sucessful in reversing Bunyoro’s recent gains against Buganda, the political-religious factionalism back home had grown worse over the early 1890s as the kingdom descended into civil war. Despite the raging conflicts, the capital remained the locus of power, and was described by a British officer as a center of prosperity and industry numbering about 70,000 inhabitants.41

In 1894, the British forced Mwanga to accept a much reduced status of protectorate, which he lacked the capacity to object to given the ruinous internecine conflicts at the court. By 1897 however, Mwanga ‘rebelled’ against the British and begun a lengthy anti-colonial war in alliance with Bunyoro that ended with his defeat and exile in 1899.42 In the following year, Buganda formally lost its autonomy, ending the kingdom’s four-century long history.

The youthful king Daudi Cwa seated on the throne, flanked by Prince Albert and Lady Elizabeth during their visit to Buganda in the early 20th century. Getty images.

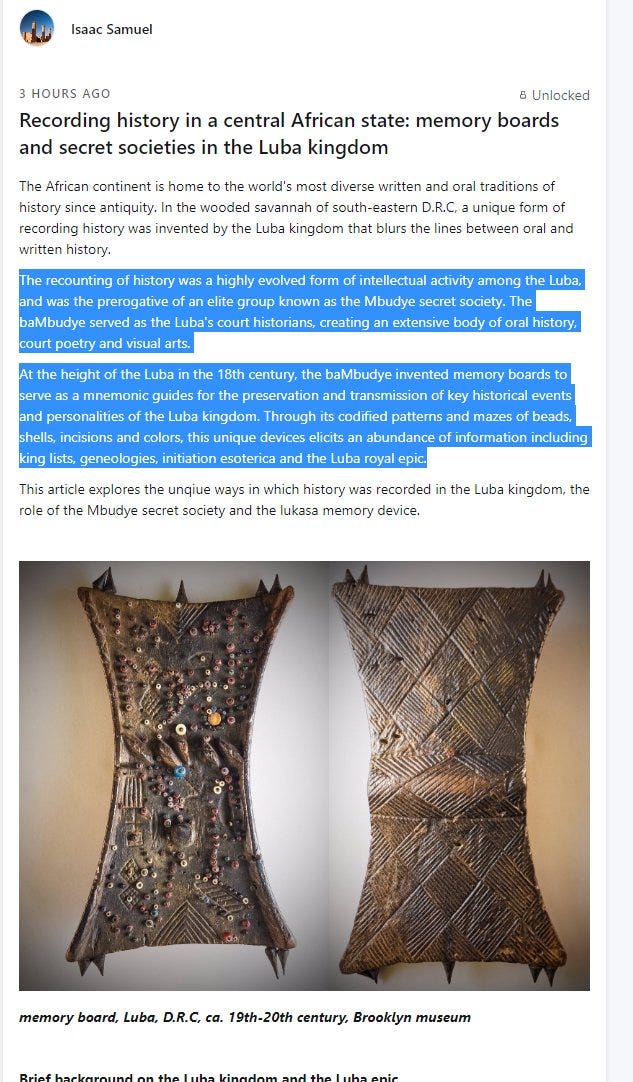

In the 18th century, a secret society in the Luba kingdom invented the Lukasa memory board, a sophisticated mnemonic device that encoded and transmitted the history of the Luba.

read more about this fascinating device on Patreon:

support my writing directly via Paypal

Map by by Jean-Pierre Chrétien

The Great Lakes of Africa: Two Thousand Years of History by Jean-Pierre Chrétien pg 54-70)

The Great Lakes of Africa: Two Thousand Years of History by Jean-Pierre Chrétien pg 88-94, Kingship and State: The Buganda Dynasty by Christopher Wrigley pg 64-65, 166-168

Kingship and State: The Buganda Dynasty by Christopher Wrigley pg 27-29, 64, 41

The Great Lakes of Africa: Two Thousand Years of History by Jean-Pierre Chrétien pg 100-101

The Great Lakes of Africa: Two Thousand Years of History by Jean-Pierre Chrétien pg 111-112

Kingship and State: The Buganda Dynasty by Christopher Wrigley pg 193-196

Political Power in Pre-Colonial Buganda by Richard Reid pg 31,79, Kingship and State: The Buganda Dynasty by Christopher Wrigley pg 29, 55-56)

Political Power in Pre-Colonial Buganda by Richard Reid pg 80

Kingship and State: The Buganda Dynasty by Christopher Wrigley pg 159-163, 199-200, 204-206

Kingship and State: The Buganda Dynasty by Christopher Wrigley pg 172-176

Political Power in Pre-Colonial Buganda by Richard Reid pg 186)

Political Power in Pre-Colonial Buganda by Richard Reid pg 72-74, 76-77, 187, The Great Lakes of Africa: Two Thousand Years of History by Jean-Pierre Chrétien pg 156

Political Power in Pre-Colonial Buganda by Richard Reid pg 188-189)

Political Power in Pre-Colonial Buganda by Richard Reid pg 191-193)

Political Power in Pre-Colonial Buganda by Richard Reid pg 196-197)

Fabrication of Empire: The British and the Uganda Kingdoms, 1890-1902 by Anthony Low pg 33-37

Sources of the African Past By David Robinson pg 80-85

The Great Lakes of Africa: Two Thousand Years of History by Jean-Pierre Chrétien pg 166-167-169

Kingship and State: The Buganda Dynasty by Christopher Wrigley pg 63)

Political Power in Pre-Colonial Buganda by Richard Reid pg 206-207, 215-217)

Kingship and State: The Buganda Dynasty by Christopher Wrigley pg 62-64)

Political Power in Pre-Colonial Buganda by Richard Reid pg 99-102)

Political Power in Pre-Colonial Buganda by Richard Reid pg 103-110)

Through the dark continent by H.M.Stanely pg 383

Bark-cloth of the Baganda people of Southern Uganda by VM Nakazibwe 62-134

Political Power in Pre-Colonial Buganda by Richard Reid pg 83-85)

Political Power in Pre-Colonial Buganda by Richard Reid pg 59)

Political Power in Pre-Colonial Buganda by Richard Reid pg 141-143)

Political Power in Pre-Colonial Buganda by Richard Reid pg pg 30, 52, 117, 139-140)

Lake Regions of Central Africa by Richard Francis Burton pg 195-196)

Political Power in Pre-Colonial Buganda by Richard Reid pg 231-236)

The Cambridge history of Africa Vol. 5 pg 283

Fabrication of Empire by Anthony Low pg 38-48

Unesco general history of Africa Vol 5 pg 370-371

The Mission of Apolo Kivebulaya by Emma Wild-Wood pg 64-65, Fabrication of Empire by Anthony Low pg 52

Political Power in Pre-Colonial Buganda by Richard Reid pg 198-201, 274)

Kingship and State: The Buganda Dynasty by Christopher Wrigley pg 67

Fabrication of Empire by Anthony Low pg 52-53, 65-66 Political Power in Pre-Colonial Buganda by Richard Reid pg 111-112)

Political Power in Pre-Colonial Buganda by Richard Reid pg 38)

Fabrication of Empire by Anthony Low pg 124, 197-210