A history of the Rozvi kingdom (1680-1830)

From Changamire's expulsion of the Portuguese to the ruined cities of Zimbabwe.

After nearly a century of unchallenged political dominance in south-eastern Africa, the Portuguese colonial project in the Mutapa kingdom was ended by the formidable armies of Chagamire Dombo, who went on to establish the Rozvi kingdom which covered most of modern Zimbabwe

The Rozvi era in southern Africa is one of the least understood periods in the region's history. In its 150 year long history, the Rozvi state was a major regional power, its elaborate political system, formidable military and iconic architecture left a remarkable legacy on modern Zimbabwe's cultural landscape.

This article explores the history of the Rozvi kingdom and its capitals, which are among Africa's most impressive ruins.

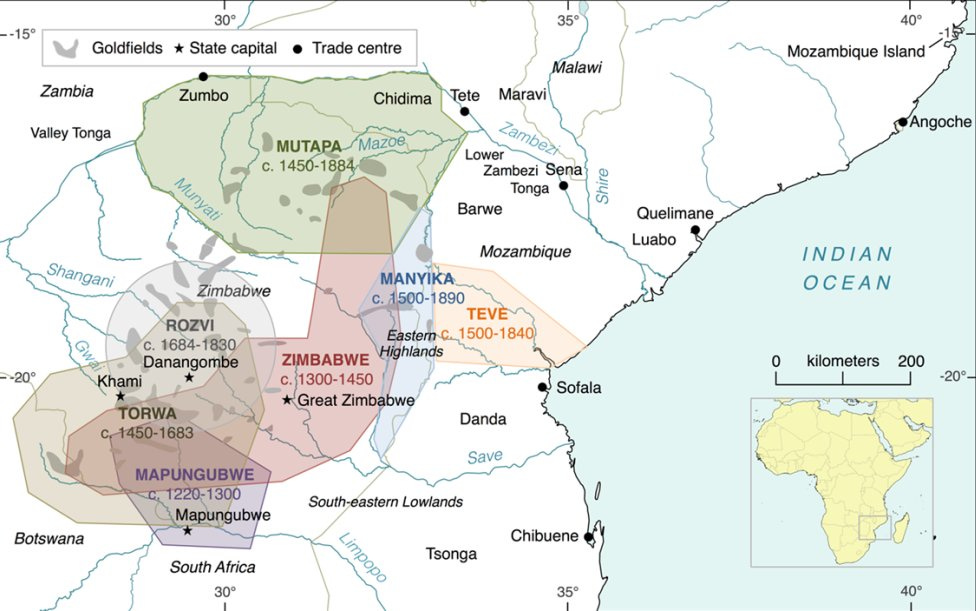

Map showing the maximum extent of Rozvi political influence in the 18th century1

Support AfricanHistoryExtra by becoming a member of our Patreon community, subscribe here to read more about African history, download free books, and keep this newsletter free for all:

Early Rozvi history and the enigmatic figure of Changamire Dombo (1670-1695)

The Rozvi state emerged during the period of political upheaval of the Portuguese colonization of Mutapa. In the century after the arrival of Francisco Barreto’s troops at the port of Sofala in 1571, the Mutapa kingdom had gradually come under Portuguese influence, formally becoming a colony in 1629. But by the close of the 17th century, the Portuguese were expelled from the Mutapa interior by the armies of an emerging power led by a ruler who they called Changamire Dombo.2

The name/title of “Changamire/Changamira” first appears in 16th century Portuguese documents associated with several foes of the Mutapa kingdom. It was first associated with a Toloa/Torwa chief who rebelled against Mukombo, the king of Mutapa around the year 1493. Mukombo was expelled from his capital but his son managed to kill the Changamire although the Torwa (who were a ruling lineage group) retained their independence. This account was recorded in 1506 at Sofala, the same port in whose hinterland another Changamire would rise in 1544 and disrupt a Portuguese invasion force.3

The Torwa lineage(s) is associated with the Butua state in south-western region of Zimbabwe and the so-called “Khami-style” ruins in the region including Khami, Naletale and Danangombe.4 While its unlikely that the Changamire who appears with the name ‘Dombo’ in the 17th century accounts is related to those mentioned in the earlier accounts, he was associated with the Torwa settlements of the south-west, especially since he was one of the southern vassals of the Mutapa ruler5. Despite living in separate states and societies, the bulk of the populations in these regions spoke the Kalanga dialect of the Shona language, and were associated with many of the old settlements and polities which emerged in the region beginning in the 10th century.6

Map showing south-eastern Africa’s political landscape from the 13th-17th century

Contemporary accounts mention that the Mutapa king Mukombwe (r. 1667-1694) granted land and wealth to Changamire Dombo around 1670, in response to an earlier conflict which pitted Dombo against a combined Mutapa-Portuguese force. However, Dombo used the wealth to attract a large following (which he called the Rozvi) and rebelled again, A combined Mutapa-Portuguese army attacked Changamire's forces in 1684 at Maungwe but Changamire defeated both of them, acquiring more land from the declining Mutapa state.7

Dombo's authority was extended to the region of Manyica around the late 17th century, requiring Portuguese miners and merchnats in the region to pay tribute. But when they refused to pay this tribute, Dombo’s forces attacked the Portuguese settlements in Manyika over the late 1680s.8 After the death of Mutapa king Makombe sometime between 1692-1694, there was a sucession dispute in which one of the candidates, Nyakunembire, allied with Changamire in 1693-1694 in a war against the Portuguese. This resulted in several devastating raids on Portuguese settlements especially Dambarare, forcing the Portuguese to evacuate all their settlements across Mutapa except at Manyika. But after Changamire descended on Manyika as well, the Portuguese withdrew to their strongholds at Tete and Sena.9

Dombo's attacks across Mutapa territory were so effective that the Portuguese relinquished their occupation of most of the Mutapa state, retaining a nominal presence using strategic political alliances. These alliances paid off when they defeated a lone force of Nyakunembire around 1695-6 and installed a puppet king named Dom Pedro to the Mutapa throne.10 This was around the time Dombo died and was suceeded by another unamed ruler who restored Rozvi control over Mutapa with a major attack in 1702 which sent the Portuguese fleeing back to Mozambique11.

The Rozvi maintained some control over Mutapa during the early 18th century, counterbalancing the Portuguese by deposing and installing allies. Most notably In 1712, when a son of Nyakunembire named Samutumbu was installed on the Mutapa throne with Rozvi support. Aware of his political weakness, Samutumbu pragmatically chose to balance his Rozvi support with a token Portuguese alliance, accepting a small garrison at his capital and received goods from Portuguese traders. The political conflict in Mutapa thereafter became a mostly internal affair as rival claimants deposed each other in close sucession. 12

The southern wing of the Rozvi state also expanded not long after Dombo’s victory at Maugwe. The Rozvi forces sacked the city of Khami in the late 1680s, the settlement was burned as its residents fled, leaving their charred possessions behind.13 The expansion of the Rozvi control over the south was directed against the cities of Danagombe, Manyanga and Naletale. While these settlements predate the Rozvi incursions of the late 17th century, the Rozvi based the core of their state in this region and continued to build their capitals in the pre-existing architectural styles.14

By the early 18th century, Rozvi control had extended from southern Zimbabwe to Manyica, Maungwe, Butua and across the Mutapa territories. Trade was restricted to stations at Zumbo on the Zambezi river and in Inhambane. The smaller chieftaincies throughout this territory remained mostly autonomous but recognized the suzeranity of the Rozvi rulers in matters of sucession and in handling the activities of foreign traders.15

Ruins of the Butua capital of Khami, read more about the history of this kingdom here:

The Rozvi kingdom, Politics, Trade and Architecture

The Rozvi state was made up of many pre-existing Kalanga polities which acknowledged the authority of the Changamire. From their impressive stone-walled towns, the Rozvi aristocracy based their rule on ownership of land and cattle, both of which were distributed to subordinate chiefs in return for tribute. They took over the rich goldfields of Butua and were also engaged in long-distance trade in ivory.16

Power in Rozvi was split between the king and a body of councilors who were in charge of adminsitration. The councilors were drawn from the Rozvi aristocracy constituting pre-existing chiefs and provincial chiefs, Rozvi royals, priests, and military leaders. The priests who were involved in the investiture of vassal chiefs and the military which enforced the king's authority, were the most important Rozvi institutions. In particular, the Rozvi army's more professionalized hierarchical structure resembled the formidable 19th century armies of the Zulu more than the pre-existing war bands found in Mutapa.17

Contemporary accounts describe the Rozvi royal court at the capital as consisting of several large stone houses within which Changamire used to store his goods. These included firearms that were bought and/or captured from the Portuguese, as well as ivory tusks which are said to have lined the walls of the royal residence. While this account was partly exaggerated, its reflected the external trade of the Rozvi rulers and the basis of their military power, as traditions recall that Dombo built his own capital on (presumably Danangombe) his own hill that was ascended by ivory steps, inorder to overshadow his rivals.18

Ruins of Danangombe

Danangombe is situated on a granite hill with a wide view of the countryside. Its central building complex consists of tow large sub-rectangular platforms disected by passages. The western platform covers 900 msq and has a retaining wall of well-fitted stone blocks rising over 6 meters while the larger eastern platform covers over 2,800 sqm and rises to a height of 3m. Its retaining walls are profusely decorated with checker, cord, herringbone and chevron patterns. The entire settlement housed an estimated population of 5,000 and inside its houses were found imported chinese porcelain, locally-worked gold jewelery, glass, copper bangles, all dated to between 1650-1815.19

Ruins of Naletale

Naletale is a ruined settlement on a granite hill situated about 5km east of Danangombe, It has the most elaborately decorated walls of the dzimbabwes with chevron, herringbone, chessboard patterns. Its elliptical enclosure wall has a diameter of 55 meters, within atleast 9 battlements which makes the ruins appear like a fortress. Like on the great zimbabwe's acropolis, there were monoliths fixed ontop of four of the 9 battlements. Naletale was an important centre though its size suggests it served as an ancillary capital of Rozvi, controlling an area with similary decorated but smaller ruins.20

ruins of Manyanga (Ntaba-za-mambo) was the last settlement associated with the Rozvi and the site of the last major battle that marked the end of Rozvi hegemony in the early 19th century. The site hasn’t been studied as much as the other two, but a survey in the 1960s found clay crucibles for smelting gold.21

The Rozvi had a largely agro-pastoral society with less external trade and mining than the Mutapa. Tribute collected from vassal chiefs often consisted of grain and cattle, but attimes included gold, ivory, which were major exports. Many of the gold mines that were taken over by the Rozvi continued operating under their control, providing a valuable product for export that would be exchanged for several imports including Indian textiles and Chinese porcelain found in several Rozvi ruins.22

However, external trade was not sufficiently important to the power of Rozvi's ruling elite, and only represented an extension of regional trade routes. Trade was not monopolized by the Rozvi rulers, who allowed subordinate chiefs and local merchnats (vashambadzi) to move from station to station trading items for local markets and for export. The vashambadzi displaced the Portuguese traders and miners who had dominated Mutapa's foreign trade during the early 17th century, and also traded on behalf of the remaining Portuguese in Rozvi territories.23

Gold objects and jewelry stolen from the ruins of Danangombe and Mundie (from: The ancient ruins of Rhodesia by Richard Hall)

So strictly was the policy of Portuguese exclusion enforced that the Portuguese captives who were taken in the battle of Manica during 1695 remained permanent prisoners in the Rozvi capital. An attempt to ransom them in 1716 failed and the captives reportedly settled down and married, for in the middle of the century, the Rozvi king asked for a priest to be sent to minister to them.24

After the Portuguese withdrew from Mutapa and recognized Rozvi authority, the only Portuguese activities in the region were limited to the activities of merchant-priests whose also handled some of Rozvi's export trade, especially at the town of Zumbo25. One such merchant-priest was the vicar of Zumbo named Pedro de Tridade who in 1743, called on the Rozvi to help secure Mutapa after the latter's descent into internecine sucession wars. The Rozvi king sent an armed force of 2,000, but the dispute was sucessful reportedly quelled before there was any need for battle.26

The Rozvi again defended the town of Zumbo during a Mutapa sucession war led by the Mutapa prince Ganiambaze. The Rozvi sent another force of about 3,000 strong to assist the town of Zumbo when it was under pressure from the Mutapa prince Casiresire. In the 1780s, the Rozvi sent an army to the kingdom of Manyika to guard Portuguese traders who were setting up a trading town in the region.27

muzzle loading cannon from the Portuguese settlement of Dambarare found at Danangombe after it was taken by Changamire’s forces

Rozvi's internal politics are less known than its external activities, traditions hold that they were factions within the Rozvi elite which split from the core state after Dombo's death. One of them moved to Hwange and established a polity among the Nambya and Tonga. Another crossed the Limpompo river and founding a polity named the Thovhela kingdom among the Venda with its capital at Dzata. The latter state appears in external accounts recorded by Dutch traders active at delagoa bay in 1730.28

Ruins of Mtoa

The last decades of the Rozvi kingdom.

The core of the Rozvi state remained largely intact as evidenced by its firm control over the trading towns in the 1770s-1780,s and as late as 1803 when Portuguese traders were requesting the Rozvi king to monopolize trade at Zumbo using his appointed agent.29 The popularized use of 'Mambo' as a dynastic title within and outside the Rozvi state, attests to the continued influence of the Changamire in ratifying the sucession of subordinate chiefs and neighboring polities who recognized him as their suzerain. Internally, fluctuating alliances and the emergence of royal houses would characterize the factionalised politics of the early 19th century.30

By the early 19th century, Rozvi was still in control of the core regions around Danangombe, Manyanga, and Khami, as well as parts of Manyica. But there were major splits during the reigns of; king Rupandamanhanga at the turn of the 19th century, and Chirisamhuru in the 1820s, which resulted in the migration of the house of Mutinhima, among others, during the early 1830s away from the core regions of the state. By then, only the lands around Danangombe and Manyanga were directly controlled by the king, while his subordinates controlled nearby regions. 31

Around the same time, Ngoni-speaking groups crossed the Limpopo in a nothern migration as they advanced into the Rozvi kingdom. The Ngoni chief Ngwana attacked the Rozvi settlements in the south during the 1820s, and other chiefs such as Zwangendaba and Maseko raided Rozvi territories before they were forced out by the remaining Rozvi armies. the swazi forces of queen Nyamazana ultimately killed Changamire Chirisamhuru and burnt his capital.32

After the death of Chirisamhuru, no sucessor was chosen by the council until the late 1840s when his son Tohwechipi was installed using Mutinhima support. Shortly before this, a large group of Nguni-speakers called the Ndebele arrived in the Rozvi region around 1830 where they were initially confronted by the Mutinhima's forces before the two groups reached a settlement. By the time the Matebele kingdom's founder Mzilikazi assumed control of his emerging state around 1840, the remaining Rozvi houses had become subordinate, a few decades prior to arrival of the colonial armies.33

Many of the walled settlements were gradually abandoned in the latter half of the 19th century, except for Manyanga which became an important religious center during the Matebele era and would become the site of a minor battle between the Matebele king Lobengula and the British in 1896. The rest of the ruins, such as Danangombe, would be plundered for gold by Cecil rhodes, while Naletale was abandoned and overgrown by vegetation.

In the year 1086, a contingent of west Africans allied with the Almoravids conquered Andalusia and created the first of the largest african diasporas in south-western Europe. For the next six centuries, African scholars, envoys and pilgrims travelled to Spain and Portugal from the regions of west africa and Kongo

read more about it here;

If you liked this article, or would like to contribute to my African history website project; please support my writing via Paypal

original map by M. Newitt

A History of Mozambique by M. D. D. Newitt pg 2, 37-38

An archaeological study of the Zimbabwe culture capital of Khami, south-western Zimbabwe by T Mukwende 7, 38

Treatise on the Rivers of Cuama' by Antonio Da Conceicao pg xxxii

Ndebele Raiders and Shona Power by D. N. Beach pg 634)

The Zimbabwe Culture by Innocent Pikirayi pg 210 Portuguese Musketeers by Richard Gray, pg 533

The changamire dombo by Kenneth C. Davy pg 200-201)

The Zimbabwe Culture by Innocent Pikirayi pg 210

Portuguese settlement on the Zambesi by M. D. D. Newitt pg 71)

'Treatise on the Rivers of Cuama' by Antonio Da Conceicao pg xxix

Portuguese settlement on the Zambesi by M. D. D. Newitt pg 72)

Great Zimbabwe: Reclaiming a 'Confiscated' Past By Shadreck Chirikure pg236,

The Zimbabwe Culture by Innocent Pikirayi pg 210-212, Ndebele Raiders and Shona Power by D. N. Beach pg 634)

Portuguese settlement on the Zambesi by M. D. D. Newitt pg 73)

The Zimbabwe Culture by Innocent Pikirayi pg 30, Becoming Zimbabwe

The Role of Foreign Trade in the Rozvi Empire by S. I. Mudenge pg 376-379, 382, The changamire dombo by Kenneth C. Davy pg 201, Becoming Zimbabwe by Brian Raftopoulos, Alois Mlambo pg 20-21

The Zimbabwe Culture by Innocent Pikirayi pg 212)

The Zimbabwe Culture by Innocent Pikirayi pg 212-214

The Zimbabwe Culture by Innocent Pikirayi pg 205-208

The Zambesian Past: Studies in Central African History edited by Eric Stokes pg 11

The Role of Foreign Trade in the Rozvi Empire by S. I. Mudenge pg 385-387)

The Role of Foreign Trade in the Rozvi Empire by S. I. Mudenge pg 387-390, A History of Mozambique by M. D. D. Newitt pg 201, 207)

Portuguese settlement on the Zambesi by M. D. D. Newitt pg 73)

'Treatise on the Rivers of Cuama' by Antonio Da Conceicao pg xxxiii-xxxvi

The Dominican Friars in Southern Africa by Philippe Denis pg 52, 59)

The Role of Foreign Trade in the Rozvi Empire by S. I. Mudenge pg 380-381)

The Zimbabwe Culture by Innocent Pikirayi pg 215)

The Role of Foreign Trade in the Rozvi Empire by S. I. Mudenge 386)

The Cambridge History of Africa. Vol 4, pg 402-403, Becoming Zimbabwe by Brian Raftopoulos, Alois Mlambo pg 21

Ndebele Raiders and Shona Power by D. N. Beach pg 635, War and Politics in Zimbabwe, 1840-1900 by D. N. Beach pg 20

A History of Mozambique by M. D. D. Newitt pg 255, 261, Ndebele Raiders and Shona Power by D. N. Beach pg 636)

Ndebele Raiders and Shona Power by D. N. Beach pg 637)

A very insightful article which also appeals to lovers of history with some information about early colonial encounters in the Rosvi state.

A much more recent account of the Rozwi state. At one time it was thought to be much earlier, I believe