A history of Women's political power and matriliny in the kingdom of Kongo.

In the 19th century, anthropologists were fascinated by the concept of matrilineal descent in which kinship is traced through the female line. Matriliny was often confounded with matriarchy as a supposedly earlier stage of social evolution than patriarchy. Matriliny thus became a discrete object of exaggerated importance, particulary in central Africa, where scholars claimed to have identified a "matrilineal belt" of societies from the D.R. Congo to Mozambique, and wondered how they came into being.

This importance of matriliny appeared to be supported by the relatively elevated position of women in the societies of central Africa compared to western Europe, with one 17th century visitor to the Kongo kingdom remarking that "the government was held by the women and the man is at her side only to help her". In many of the central African kingdoms, women could be heads of elite lineages, participate directly in political life, and occasionally served in positions of independent political authority. And in the early 20th century, many speakers of the Kongo language claimed to be members of matrilineal clans known as ‘Kanda’.

Its not difficult to see why a number of scholars would assume that Kongo may have originally been a matrilineal —or even matriarchal— society, that over time became male dominated. And how this matrilineal African society seems to vindicate the colonial-era theories of social evolution in which “less complex” matriarchal societies grow into “more complex” patriarchal states. As is often the case with most social histories of Africa however, the contribution of women to Kongo’s history was far from this simplistic colonial imaginary.

Support African History Extra by becoming a member of our Patreon community, subscribe here to read more on African history and keep this blog free for all:

Scholars have often approached the concept of matriliny in central Africa from an athropological rather than historical perspective. Focusing on how societies are presently structured rather than how these structures changed through time.

One such prominent scholar of west-central Africa, Jan Vansina, observed that matrilineal groups were rare among the foragers of south-west Angola but common among the neighboring agro-pastoralists, indicating an influence of the latter on the former. Vansina postulated that as the agro-pastoral economy became more established in the late 1st millennium, the items and tools associated with it became highly valued property —a means to accumulate wealth and pass it on through inheritance. Matrilineal groups were then formed in response to the increased importance of goods, claims, and statuses, and hence of their inheritance or succession. As leadership and sucession were formalised, social alliances based on claims to common clanship, and stratified social groups of different status were created.1

According to Vansina, only descent through the mother’s line was used to establish corporate lineages headed by the oldest man of the group, but that wives lived patrilocally (ie: in their husband's residence). He argues that the sheer diversity of kinship systems in the region indicates that matriliny may have developed in different centers along other systems. For example among the Ambundu, the Kongo and the Tio —whose populations dominated the old kingdoms of the region— matrilineages competed with bilateral descent groups. This diverse framework, he suggests, was constantly remodeled by changes in demographics and political development.2

Yet despite their apparent ubiquity, matrilineal societies were not the majority of societies in the so-called matrilineal belt. Studies by other scholars looking at societies in the Lower Congo basin show that most of them are basically bilateral; they are never unequivocally patrilineal or matrilineal and may “oscillate” between the two.3 More recent studies by other specialists such as Wyatt MacGaffey, argue that there were never really any matrilineal or patrilineal societies in the region, but there were instead several complex and overlapping forms of social organization (regarding inheritance and residency) that were consistently changed depending on what seemed advantageous to a give social group.4

Moving past contemporary debates on the existance of Matriliny, most scholars agree that the kinship systems in the so-called matrilineal belt was a product of a long and complex history. Focusing on the lower congo river basin, systems of mobilizing people often relied on fictive kinship or non-kinship organizations. In the Kongo kingdom, these groups first appear in internal documents of the 16th-17th century as political factions associated with powerful figures, and they expanded not just through kinship but also by clientage and other dependents. In this period, political loyalty took precedence over kinship in the emerging factions, thus leading to situations where rivaling groups could include people closely related by descent.5

Kongo's social organization at the turn of the 16th-17th century did not include any known matrilineal descent groups, and that the word 'kanda' —which first appears in the late 19th/early 20th century, is a generic word for any group or category of people or things6. The longstanding illusion that 'kanda' solely meant matrilineage was based on the linguistic error of supposing that, because in the 20th century the word kanda could mean “matriclan” its occurrence in early Kongo was evidence of matrilineal descent.7 In documents written by Kongo elites, the various political and social groupings were rendered in Portuguese as geracao, signifying ‘lineage’ or ‘clan’ as early as 1550. But the context in which it was used, shows that it wasn’t simply an umbrella term but a social grouping that was associated with a powerful person, and which could be a rival of another group despite both containing closely related persons.8

In Kongo, kinship was re-organized to accommodate centralized authority and offices of administration were often elective or appointive rather than hereditary. Kings were elected by a royal council comprised of provincial nobles, many of whom were themselves appointed by the elected Kings, alongside other officials. The kingdom's centralized political system —where even the King was elected— left a great deal of discretion for the placement of people in positions of power, thus leaving relatively more room for women to hold offices than if sucession to office was purely hereditary. But it also might weaken some women's power when it was determined by their position in kinship systems.9

Aristocratic women of Kongo, ca. 1663, the Parma Watercolors.

Kongo's elite women could thus access and exercise power through two channels. The first of these is appointment into office by the king to grow their core group of supporters, the second is playing the strategic role of power brokers, mediating disputes between rivalling kanda or rivaling royals.

Elite women appear early in Kongo's documented history in the late 15th century when the adoption of Christianity by King Nzinga Joao's court was opposed by some of his wives but openly embraced by others, most notably the Queen Leonor Nzinga a Nlaza. Leonor became an important patron for the nascent Kongo church, and was closely involved in ensuring the sucession of her son Nzinga Afonso to the throne, as well as Afonso's defeat of his rival brother Mpanzu a Nzinga.10

Leonor held an important role in Kongo’s politics, not only as a person who controlled wealth through rendas (revenue assignments) held in her own right, but also as a “daughter and mother of a king”, a position that according to a 1530 document such a woman “by that custom commands everything in Kongo”. Her prominent position in Kongo's politics indicates that she wielded significant political power, and was attimes left in charge of the kingdom while Afonso was campaigning.11

Not long after Leonor Nzinga’s demise appeared another prominent woman named dona Caterina, who also bore the title of 'mwene Lukeni' as the head of the royal kanda/lineage of the Kongo kingdom's founder Lukeni lua Nimi (ca. 1380). This Caterina was related to Afonso's son and sucessor Pedro, who was installed in 1542 but later deposed and arrested by his nephew Garcia in 1545. Unlike Leonor however, Caterina was unsuccessful in mediating the factious rivary between the two kings and their supporters, being detained along with Pedro.12

In the suceeding years, kings drawn from different factions of the lukeni lineage continued to rule Kongo until the emergence of another powerful woman named Izabel Lukeni lua Mvemba, managed to get her son Alvaro I (r. 1568-1587) elected to the throne. Alvaro was the son of Izabel and a Kongo nobleman before Izabel later married Alvaro's predecessor, king Henrique, who was at the time still a prince. But after king Henrique died trying to crush a jaga rebellion in the east, Alvaro was installed, but was briefly forced to flee the capital which was invaded by the jagas before a Kongo-Portugal army drove them off. Facing stiff opposition internally, Alvaro relied greatly on his mother; Izabel and his daughter; Leonor Afonso, to placate the rivaling factions. The three thereafter represented the founders of the new royal kanda/house of kwilu, which would rule Kongo until 1624.13

Following in the tradition of Kongo's royal women, Leonor Afonso was a patron of the church. But since only men could be involved in clerical capacities, Leonor tried to form an order of nuns in Kongo, following the model of the Carmelite nuns of Spain. She thus sent letters to the prioress of the Carmelites to that end. While the leader of the Carmelite mission in Kongo and other important members of the order did their best to establish the nunnery in Kongo, the attempt was ultimately fruitless. Leonor neverthless remained active in Kongo's Church, funding the construction of churches, and assisting the various missions active in the kingdom. Additionally, the Kongo elite created female lay associations alongside those of men that formed a significant locus of religiosity and social prestige for women in Kongo.14

As late as 1648, Leonor continued to play an important role in Kongo's politics, she represented the House of kwilu started by king Alvaro and was thus a bridge, ally or plotter to the many descendants of Alvaro still in Kongo. One visiting missionary described her as “a woman of very few words, but much judgment and government, and because of her sage experience and prudent counsel the king Garcia and his predecessor Alvaro always venerate and greatly esteem her and consult her for the best outcome of affairs". This was despite both kings being drawn from a different lineage, as more factions had appeared in the intervening period.15

The early 17th century was one of the best documented periods in Kongo's history, and in highlighting the role of women in the kingdom's politics and society. Alvaro's sucessors, especially Alvaro II and III, appointed women in positions of administration and relied on them as brokers between the various factions. When Alvaro III died without an heir, a different faction managed to get their candidate elected as King Pedro II (1622-1624). Active at Pedro's royal council were a number of powerful women who also included women of the Kwilu house such as Leonor Afonso, and Alvaro II's wife Escolastica. Both of them played an important role in mediating the transition from Alvaro III and Pedro II, at a critical time when Portugual invaded Kongo but was defeated at Mbanda Kasi.16

Besides these was Pedro II's wife Luiza, who was now a daughter and mother of a King upon the election of her son Garcia I to suceed the short-lived Pedro. However, Garcia I fell out of favour with the other royal women of the coucil (presumably Leonor and Escolastica), who were evidently now weary of the compromise of electing Pedro that had effectively removed the house of Kwilu from power. The royal women, who were known as “the matrons”, sat on the royal council and participated in decision making. They thus used the forces of an official appointed by Alvaro III, to depose Garcia I and install the former's nephew Ambrosio as king of Kongo.17

However, the kwilu restoration was short-lived as kings from new houses suceeded them, These included Alvaro V of the 'kimpanzu' house, who was then deposed by another house; the ‘kinlaza’, represented by kings Alvaro VI (r. 1636-1641) and Garcia II (r. 1641-1661) . Yet throughout this period, the royal women retained a prominent position on Kongo's coucil, with Leonor in particular continuing to appear in Garcia II's court. Besides Leonor Afonso was Garcia II's sister Isabel who was an important patron of Kongo's church and funded the construction of a number of mission churches. Another was a second Leonor da Silva who was the sister of the count of Soyo (a rebellious province in the north), and was involved in an attempt to depose Garcia II.18

In some cases, women ruled provinces in Kongo during the 17th century and possessed armies which they directed. The province of Mpemba Kasi, just north of the capital, was ruled by a woman with the title of 'mother of the King of Kongo', while the province of Nsundi was jointly ruled by a duchess named Dona Lucia and her husband Pedro, the latter of whom at one point directed her armies against her husband due to his infidelity. According to a visiting priest in 1664, the power exercised by women wasn't just symbolic, "the government was held by the women and the man is at her side only to help her". However, the conflict between Garcia II and the count of Soyo which led to the arrest of the two Leonors in 1652 and undermined their role as mediators, was part of the internal processes which eventually weakened the kingdom that descended into civil war after 1665.19

In the post-civil war period, women assumed a more direct role in Kongo's politics as kingmakers and as rulers of semi-autonomous provinces. After the capital was abandoned, effective power lay in regional capitals such as Mbanza Nkondo which was controlled by Ana Afonso de Leao, and Luvota which was controlled by Suzanna de Nobrega. The former was the sister of Garcia II and head of his royal house of kinlaza, while the latter was head of the kimpanzu house, both of these houses would produce the majority of Kongo's kings during their lifetimes, and continuing until 1914. Both women exercised executive power in their respective realms, they were recognized as independent authorities during negotiations to end the civil war, and their kinsmen were appointed into important offices.20

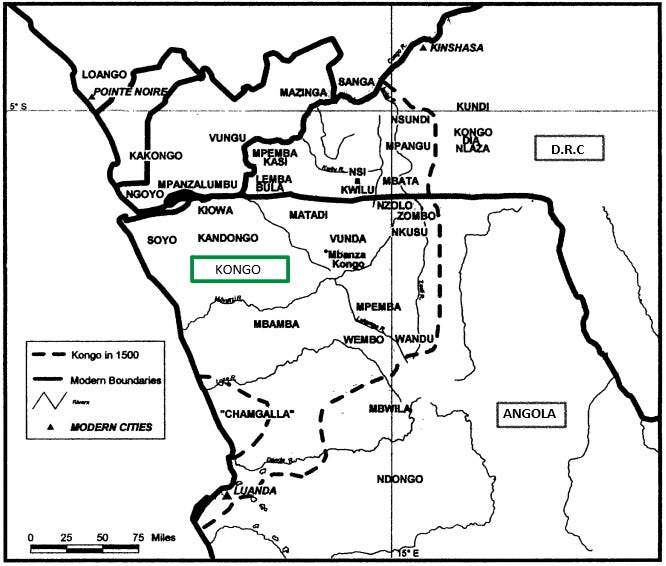

Map of Kongo around 1700.

The significance of Kongo's women in the church increased in the late 17th to early 18th century. Queen Ana had a reputation for piety, and even obtained the right to wear the habit of a Capuchin monk, and an unamed Queen who suceeded Suzanna at Luvota was also noted for her devotion. It was in this context that the religious movement led by a princess Beatriz Kimpa Vita, which ultimately led to the restoration of the kingdom in 1709. Her movement further "indigenized" the Kongo church and elevated the role of women in Kongo's society much like the royal women had been doing. 21

For the rest of the 18th century, many women dominated the political landscape of Kongo. Some of them, such as Violante Mwene Samba Nlaza, ruled as Queen regnant of the 'kingdom' of Wadu. The latter was one of the four provinces of Kongo but its ruler, Queen Violante, was virtually autonomous. She appointed dukes, commanded armies which in 1764 attempted to install a favorable king on Kongo's throne and in 1765 invaded Portuguese Angola. Violante was later suceeded as Queen of Wadu by Brites Afonso da Silva, another royal woman who continued the line of women sovereigns in the kingdom.22

Women in Kongo continued to appear in positions of power during the 19th century, albeit less directly involved in the kingdom's politics as consorts of powerful merchants, but many of them were prominent traders in their own right23. Excavations of burials from sites like Kindoki indicate that close social groups of elites were interred in the same cemetery complex alongside rich grave goods as well as Christian insignia of royalty. Among these elites were women who were likely consorts or matriarchs of the male relatives buried alongside them. The presence of initiatory items of kimpasi society as well as long distance trade goods next to the women indicates their relatively high status.24

It’s during this period that the matrilineal ‘kandas’ first emerged near the coastal regions, and were most likely associated with the commercial revolutions of the period as well as contests of legitimacy and land rights in the early colonial era.25 The social histories of these clans were then synthesized in traditional accounts of the kingdom’s history at the turn of the 20th century, and uncritically reused by later scholars as accurate reconstructions of Kongo’s early history. While a few of the clans were descended from the old royal houses (which were infact patrilineal), the majority of the modern clans were relatively recent inventions.26

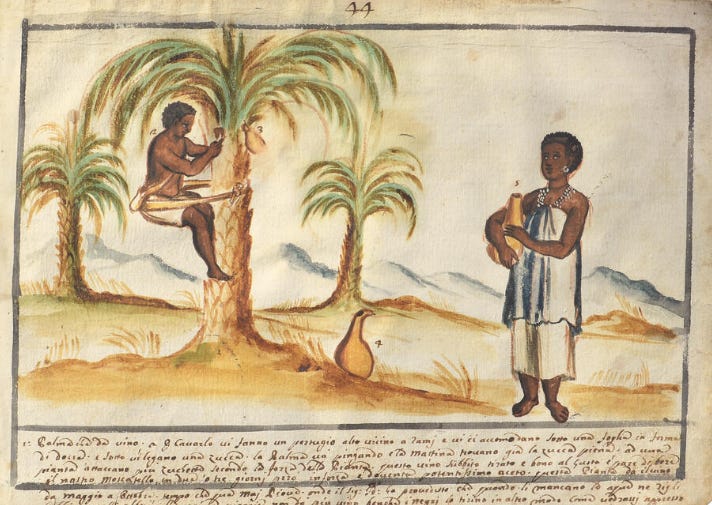

17th century illustration of Kongo titled “Palm tree that gives wine”, showing a woman with a gourd of palm wine. During the later centuries, women dominated the domestic trade in palm wine especially along important carravan routes in the kingdom.27

The above overview of women in Kongo's history shows that elite women were deeply and decisively involved in the political and social organization of the Kongo kingdom. In a phenomenon that is quite exceptional for the era, the political careers of several women can be readily identified; ranging from shadowy but powerful figures in the early period, to independent authorities during the later period.

This outline also reveals that the organization of social relationships in Kongo were significantly influenced by the kingdom's political history. The kingdom’s loose political factions and social groups which; could be headed by powerful women or men; could be created upon the ascension of a new king; and didn't necessary contain close relatives, fail to meet the criteria of a historically 'matrilineal society'.

Ultimately, the various contributions of women to Kongo's history were the accomplishments of individual actors working against the limitations of male-dominated political and religious spaces to create one of Africa’s most powerful kingdoms.

The ancient libraries of Africa contain many scientific manuscripts written by African scholars. Among the most significant collections of Africa’s scientific literature are medical manuscripts written by west African physicians between the 15th and 19th century.

Read more about them here:

How Societies Are Born by Jan Vansina pg 92-95, 99

How Societies Are Born by Jan Vansina pg 88-97)

The Kongo Kingdom: The Origins, Dynamics and Cosmopolitan Culture of an African Polity by Koen Bostoen, Inge Brinkman pg 50)

Changing Representations in Central African History by Wyatt Macgaffey pg 197-201)

Elite women in the kingdom of Kongo by J.K.Thornton pg 440)

Changing Representations in Central African History by Wyatt Macgaffey pg 200

The Kongo Kingdom: The Origins, Dynamics and Cosmopolitan Culture of an African Polity by Koen Bostoen, Inge Brinkman pg 50, A note on Vansina’s invention of matrilinearity by Wyatt Macgaffey pg 270-271

Elite women in the kingdom of Kongo by J.K.Thornton pg 439-440

Elite women in the kingdom of Kongo by J.K.Thornton pg pg 439)

Elite women in the kingdom of Kongo by J.K.Thornton pg 442-443)

A History of West Central Africa to 1850 by John Thornton pg 40

Elite women in the kingdom of Kongo by J.K.Thornton pg 444-445)

Elite women in the kingdom of Kongo by J.K.Thornton pg 446)

A Kongo Princess, the Kongo Ambassadors and the Papacy by Richard Gray, Elite women in the kingdom of Kongo by J.K.Thornton pg 447, The Kongo Kingdom: The Origins, Dynamics and Cosmopolitan Culture of an African Polity by Koen Bostoen, Inge Brinkman pg 155-156)

Elite women in the kingdom of Kongo by J.K.Thornton pg 452-453)

Elite women in the kingdom of Kongo by J.K.Thornton pg 449)

A History of West Central Africa to 1850 by John Thornton pg 148-149

Elite women in the kingdom of Kongo by J.K.Thornton pg 452-453)

Elite women in the kingdom of Kongo by J.K.Thornton pg 454)

The Kongolese Saint Anthony by John Thornton pg 24-39, Elite women in the kingdom of Kongo by J.K.Thornton pg 455-456

Elite women in the kingdom of Kongo by J.K.Thornton pg 457, The Kongo Kingdom: The Origins, Dynamics and Cosmopolitan Culture of an African Polity by Koen Bostoen, Inge Brinkman pg 153)

Elite women in the kingdom of Kongo by J.K.Thornton pg 459-460)

Kongo in the age of empire by Jelmer Vos pg 47, 53

The Kongo Kingdom: The Origins, Dynamics and Cosmopolitan Culture of an African Polity by Koen Bostoen, Inge Brinkman pg 157-158)

A note on Vansina’s invention of matrilinearity by Wyatt Macgaffey pg 279, Kongo Political Culture: The Conceptual Challenge of the Particular By Wyatt MacGaffey pg 62-63

Origins and early history of Kongo by J. K Thornton. pg 93-98.

Kongo in the age of empire by Jelmer Vos pg 43, 53.