A muslim kingdom in the Ethiopian highlands: the history of Ifat and Adal ca. 1285-1520.

During the late Middle Ages, the northern Horn of Africa was home to some of the continent's most powerful dynasties, whose history significantly shaped the region's social landscape.

The history of one of these dynasties, often referred to as the Solomonids, has been sufficiently explored in many works of African history. However, the history of their biggest political rivals, known as the Walasma dynasty of Ifat, has received less scholarly and public attention, despite their contribution to the region’s cultural heritage.

This article outlines the history of the Walasma kingdoms of Ifat and Adal, which influenced the emergence and growth of many Muslim societies in the northern Horn of Africa.

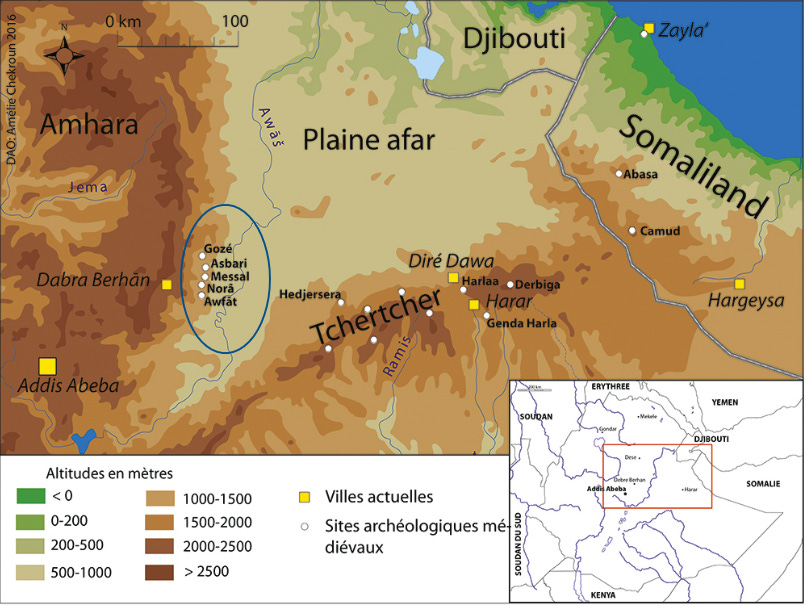

Map of the northern Horn of Africa during the early 16th century.1

Support AfricanHistoryExtra by becoming a member of our Patreon community, and keep this newsletter free for all:

Background to the Ifat kingdom: the enigmatic polity of Šawah.

Near the end of the 13th century, an anonymous scholar in the northern Horn of Africa composed a short chronicle titled Ḏikr at-tawārīḫ (ie: “the Annals”), that primarily dealt with the rise and demise of a polity called ‘Šawah’ which flourished from 1063 to 1290 CE. The text describes the sultanate of Šawah as comprised of several urban settlements, with the capital at Walalah, and outlying towns like Kālḥwr, and Ḥādbayah, that were controlled by semi-autonomous rulers of a dynasty called the Maḫzūmī.2

The author of the Ḏikr at-tawārīḫ's notes the presence of a scholarly elite in Šawah, was aware of the sack of Baghdad in 1258 by the ‘Tatars’ (Mongols) , and mentions that the state’s judicial system was headed by a ‘qāḍī al-quḍā’ (ie: “cadi of the cadis”). The text also mentions a few neighboring Muslim societies like Mūrah, ʿAdal, and Hūbat. The information provided in the chronicle is corroborated by a Mumluk-Egyptian text describing an Ethiopian embassy in 1292, which notes that “Among the kings of Abyssinia is Yūsuf b. Arsmāya, master of the territory of Ḥadāya, Šawā, Kalǧur, and their districts, which are dominated by Muslim kings.”3

The composition of the chronicle of Šawah represents an important period in the emergence of Muslim societies in north-eastern regions of modern Ethiopia, which also appears extensively across the region’s archeological record, where many inscribed tombs, mosques, and imported goods were found dated between the 11th and 15th century, particularly in the region of Harlaa.

While the towns of Šawah are yet to be found, the remains of contemporaneous Muslim societies were generally urbanized and were associated with long-distance trade that terminated at the coastal city of Zayla. It’s in this context that the kingdom of Ifāt (ኢፋት) emerged under its founder Wālī ʾAsmaʿ (1285–1289), whose state eclipsed and subsumed most of the Muslim polities across the region including Šawā.4

Important polities in the northern Horn during the late middle ages, including the Muslim states of Ifat, Adal, Hadya and Sawah.5

The Walasma kingdom of Ifat during the 14th century.

In the late 13th century, Wālī Asma established an alliance with Yǝkunno Amlak —founder of the Solomonic dynasty of the medieval Christian kingdom of Ethiopia— acknowledging the suzerainty of the latter in exchange for military support. Wālī ʾAsma’s growing power threatened the last ruler of Šawah; Sultan Dilmārrah, who attempted to appease the former through a marital alliance in 1271. Ultimately, the armies of Wālī Asma attacked Šawah in 1277, deposed its Maḫzūmī rulers, and imposed their power on the whole region, including the polities at Mūrah, ʿAdal, and Hūbat, which were conquered by 1288.6

The establishment of the Ifat kingdom coincided with the expansion of the power of the Solomonids, who subsumed many neighboring states including Christian kingdoms like Zagwe, as well as Muslim and 'pagan' kingdoms. By the 14th century, the balance of power between the Solomonids and the Walasma favored the former. The rulers of Ifat were listed among the several tributaries mentioned in the chronicle of the ʿAmdä Ṣǝyon (r. 1314-1344), whose armies greatly expanded the Solomonid state. The Walasma sultan then sent an embassy to Mamluk Egypt’s sultan al-Nasir in 1322 to intercede with Amdä Ṣǝyon on behalf of the Muslims.7

It’s during this period that detailed descriptions of Ifat appear in external texts, primarily written by the Mamluks, such as the accounts of Abū al-Fidā' (1273-1331) and later al-Umari in the 1330s. According to al-Fidā' the capital of Ifat was "one of the largest cities in the Ḥabašā [Ethiopia]. There are about twenty stages between this town and Zayla. The buildings of Wafāt are scattered. The abode of royalty is on one hill and the citadel is on another hill". Al-Umari writes that Ifat was the most important of the "seven kingdoms of Muslim Abyssinia." He adds that "Awfāt is closest to Egyptian territory and the shores facing Yemen and has the largest territory. Its king reigns over Zaylaʿ; it is the name of the port where merchants going to this kingdom approach."8

The Sultanate of Ifat is the best documented among the Muslim societies of the northern Horn during the Middle Ages, and its archeological sites are the best studied. The account of the 14th-century account of al-Umari and the 15th-century chronicle of Amdä Ṣeyon (r. 1314-1344) both describe several cities in the territory of Ifat that refer to the provincial capitals of the kingdom. These textural accounts are corroborated by the archeological record, with at least five ruined cities —Asbari, Masal, Rassa Guba, Nora, and Beri-Ifat— having been identified in its former territory and firmly dated to the 14th century.9

ruins of the mosques at Beri-Ifat and Nora.10

Location of the archeological sites of Ifat and the kingdom’s center.

The largest archeological sites at Nora, Beri-Ifat, and Asbari had city walls, remains of residential buildings preserved to a height of over 2-3 meters, and an urban layout with streets and cemeteries, set within a terraced landscape. The material culture of the sites includes some imported wares from the Islamic world, but was predominantly local, and included iron rods that were used as currency. Each of the cities and towns possessed a main mosque in addition to neighborhood mosques (or oratories) in larger cities like Nora, built in a distinctive architectural style that characterized most of the settlements in Ifat.11

The above archeological discoveries corroborate al-ʿUmarī’s account, which notes that “there are, in these seven kingdoms, cathedral mosques, ordinary mosques and oratories.”, and the city layout of Beri-Ifat is similar to the account provided by al-Fidā', who notes that the capital’s buildings were scattered. The discovery of inscribed tombs of a “sheikh of the Walasmaʿ” of Šāfiʿite school who died in 1364, also corroborates al-Umari's accounts of this school's importance in Ifat, as well as the providing evidence for the origin of the diasporic scholarly community known as the Zaylāiʿ at the important Shāfiʿī college of al-Azhar in Cairo.12

Mosque of Ferewanda, part of the city of Beri-Ifat.

Square house with a wall niche at the site of Nora

Tomb T8 near the sultan’s residence close to the mosque of Beri-Ifat. It belongs to sultan al-Naṣrī b. ʿAlī [Naṣr] b. Ṣabr al-Dīn b. Wālāsma, and is dated Saturday 15 ṣafar 775 h., [i.e. August 6, 1373]

Trade, warfare, and the decline of Ifat.

According to Al-ʿUmarī, the kingdom of Ifat dominated trade because of its geographical position near the coast and its control of Zayla, from where imports of “silk and linen fabrics" were obtained. Later accounts describe trading cities like “Manadeley” where one could "find every kind of merchandise that there is in the world, and merchants of all nations, also all the languages of the Moors, from Giada, from Morocco, Fez, Bugia, Tunis, Turks, Roumes from Greece, Moors of India, Ormuz and Cairo".13

Another important trading city of Ifat was Gendevelu, which appears in internal accounts as Gendabelo since the 14th century and likely corresponds to the archeological site of Asbari. External descriptions of the city mention "caravans of camels unload their merchandise" and "the currency is Hungarian and Venetian ducats, and the silver coins of the Moors." While the rulers of Ifat didn’t mint their own coins, most sources note the use of imported silver coins, as well as commodity currencies like cloth and iron rods.14

The main mosque of Asbari.15

Much of the political history of Ifat was provided in an internal chronicle titled 'Taʾrīḫ al-Walasmaʿ written in the 16th century, as well as an external account by the Mamluk historian al-Maqrīzī in 1438. Both texts describe a major dynastic split in the Walasma family of Ifat that occurred in the late 14th century, between those who wanted to continue recognizing the suzerainty of the Solomonids, and those who rejected it. According to al-Maqrizi, the Solomonids could install and depose the Walasma rulers at will, retain some of the Ifat royals at their court, and often provided military aid to those allied with them.16

In the 1370s, sultan Ali of Ifat was aided by the armies of the Ethiopian emperor in fighting a rebellion led by Ali's rival Ḥaqq al-Dīn (r. 1376–1386), who established a separate kingdom away from the capital. After the destruction of the Ifat capital during the dynastic conflict, and the death of Ḥaqq al-Dīn in a war with the Solomonids, his brother Saʿd al-Dīn continued the rebellion but was defeated near Zayla around 140917. In response to the continuous conflict, the Solomonids formerly incorporated the territories of Ifat, appointed Christian governors who adopted the name Walasmaʿ (in Gǝʿǝz, wäläšma), deployed garrisons of their own soldiers, and established royal capitals in Ifat territory.18

The mosque of Jéʾértu.19

The re-establishment of Walasma power in the 15th century until their demise in 1520.

After the death of Saʿd al-Dīn, his family took refuge in Yemen, at the court of the Rasūlid sultan Aḥmad b. al-Ašraf Ismāʿil (r. 1400–1424). Saʿd al-Dīn's oldest son, Ṣabr al-Dīn (r. 1415–1422), later came back to Ethiopia, to a place called al-Sayāra, in the eastern frontier of the province of Ifat, where the soldiers who had served under his father joined him. They established a new sultanate, called Barr Saʿd al-Dīn (“Land of Saʿd al-Dīn”) which appears as Adal in the chronicles of the Solomonid rulers, who were by then in control of the territory of Ifat.20

Beginning in 1433, the Walasma rulers of Barr Saʿd al-Dīn established their capital at Dakar, which likely corresponds to the ruined sites of Derbiga and Nur Abdoche located near the old city of Harar. They imposed their power over many pre-existing Muslim polities including Hūbat, the city of Zaylaʿ, the Ḥārla region surrounding Harar, and parts of northern Somalia. An emir was appointed by the sultan to head each territory, with the prerogative of levying taxes (ḫarāǧ and zakāt) on the population.21

The Derbiga mosque in 192222

The Walasma rulers at Dakar reportedly maintained fairly cordial relations with the Solomonids in order to facilitate trade, but wars between their two states continued especially during the reigns of the sultans Ṣabr al-Dīn (r. 1415–1422), Manṣūr (r. 1422–1424), Ǧamāl al-Dīn (r. 1424–1433) and Badlāy (r. 1433–1445). Repeated incursions into 'Adal' by the armies of the Solomonid monarchs compelled some of the former's dependents to pay tribute to the latter, and in 1480, Dakar itself was sacked by the armies of Eskender (r. 1478-1494).23

However, by the early 16th century, the armies of the Walasma begun conducting their own incursions into the Solomonid state. The sultan Muḥammad b. Saʿd ad-Dıˉn, who had the longest reign from 1488 to around 1517, is known to have undertaken annual expeditions against the territories controlled by the Solomonids. After the death of Sultan Muḥammad, the kingdom experienced a period of instability during which several illegitimate rulers followed each other in close succession and a figure named Imām Aḥmad rose to prominence.24

The tumultuous politics of this period are described in detail by two internal chronicles written during this period. The first one, titled Taʾrıkh al-Walasmaʿ, was in favor of Sultan Muḥammad’s only legitimate successor, Sultan Abū Bakr (r. 1518-1526), while the other chronicle, Taʾrıkh al-muluk, favored Imām Aḥmad’s camp. Both agree on the shift of the sultanate’s capital from Dakar to the city of Harar in July 1520, but the former text ends with this event while the latter begins with it. This shift marked the decline of Sultan Abū Bakr’s power and was followed by his death at the hands of Imām Aḥmad who effectively became the real authority in the sultanate, while the Walasma lost their authority25.

Imām Aḥmad would then undertake a series of campaigns that eventually brought most of the territory controlled by the Solomonids under his control, briefly creating one of Africa’s largest empires at the time, and beginning a new era in the region’s history.

Panorama of Harar and its hinterland in 1944, quai branly

The ancient coast of East Africa was part of an old trading system linking the Roman world to the Indian Ocean world, with the metropolis of Rhapta in Tanzania being one of the major African cities known to classical geographers.

Read more about the ancient East African coast and its links to the Roman world here:

Map by Matteo Salvadore

Le Dikr at-tawārīḫ (dite Chronique du Šawā) : nouvelle édition et traduction du Vatican arabe 1792, f. 12v-13r by Damien Labadie, A Companion to Medieval Ethiopia and Eritrea, edited by Samantha Kelly pg 93-94)

A Companion to Medieval Ethiopia and Eritrea, edited by Samantha Kelly pg 94-95)

A Companion to Medieval Ethiopia and Eritrea, edited by Samantha Kelly pg 95-96)

Map by Taddesse Tamrat

A Companion to Medieval Ethiopia and Eritrea, edited by Samantha Kelly pg 94, 99)

Ethiopia and the Red Sea The Rise and Decline of the Solomonic Dynasty and Muslim European Rivalry in the Region by Mordechai Abir pg 22-24, A Companion to Medieval Ethiopia and Eritrea, edited by Samantha Kelly pg 99-100)

Le sultanat de l’Awfāt, sa capitale et la nécropole des Walasma by François-Xavier Fauvelle, Bertrand Hirsch et Amélie Chekroun, prg 6, 61-62)

A Companion to Medieval Ethiopia and Eritrea, edited by Samantha Kelly pg 106, Le sultanat de l’Awfāt, sa capitale et la nécropole des Walasma by François-Xavier Fauvelle, Bertrand Hirsch et Amélie Chekroun prg 26-28)

this and all other photos (except where stated) are from the French Archaeological Mission, 2008, 2009, 2010 led by François-Xavier Fauvelle

Le sultanat de l’Awfāt, sa capitale et la nécropole des Walasma by François-Xavier Fauvelle, Bertrand Hirsch et Amélie Chekroun prg 29-40, 55-59)

Le sultanat de l’Awfāt, sa capitale et la nécropole des Walasma by François-Xavier Fauvelle, Bertrand Hirsch et Amélie Chekroun prg 63, 77, A Companion to Medieval Ethiopia and Eritrea, edited by Samantha Kelly pg 106-107.

A Companion to Medieval Ethiopia and Eritrea, edited by Samantha Kelly pg 108-109, 110-111)

In Search of Gendabelo, the Ethiopian “Market of the World” of the 15th and 16th Centuries by Amélie Chekroun, Ahmed Hassen Omer and Bertrand Hirsch

photo from the Nora/Gendebelo Program 2009

A Companion to Medieval Ethiopia and Eritrea, edited by Samantha Kelly pg 100)

Entre Arabie et Éthiopie chrétienne : le sultan walasma‘ Sa‘d al-Dīn et ses fils by Amélie Chekroun

Le sultanat de l’Awfāt, sa capitale et la nécropole des Walasma by François-Xavier Fauvelle, Bertrand Hirsch et Amélie Chekroun prg 66-73, Ethiopia and the Red Sea The Rise and Decline of the Solomonic Dynasty and Muslim European Rivalry in the Region by Mordechai Abir pg 26-27.

Notes on the survey of Islamic Archaeological sites in South-Eastern Wallo (Ethiopia) by Deresse Ayenachew and Assrat Assefa

A Companion to Medieval Ethiopia and Eritrea, edited by Samantha Kelly pg 102

Dakar, capitale du sultanat éthiopien du Barr Sa‘d addīn by Amélie Chekroun, A Companion to Medieval Ethiopia and Eritrea, edited by Samantha Kelly 108, Harar as the capital city of the Barr Saʿd ad-Dıˉn by Amélie Chekroun pg 27-28

photo by Azaïs & Chambard 1931

Ethiopia and the Red Sea The Rise and Decline of the Solomonic Dynasty and Muslim European Rivalry in the Region by Mordechai Abir pg 31-32, A Companion to Medieval Ethiopia and Eritrea, edited by Samantha Kelly pg 104, Dakar, capitale du sultanat éthiopien du Barr Sa‘d addīn by Amélie Chekroun prg 8)

Harar as the capital city of the Barr Saʿd ad-Dıˉn by Amélie Chekroun pg 32-33

Harar as the capital city of the Barr Saʿd ad-Dıˉn by Amélie Chekroun pg 34-34, Dakar, capitale du sultanat éthiopien du Barr Sa‘d addīn by Amélie Chekroun