Africans in the Indian Ocean world and the autobiography of a Somali Globetrotter.

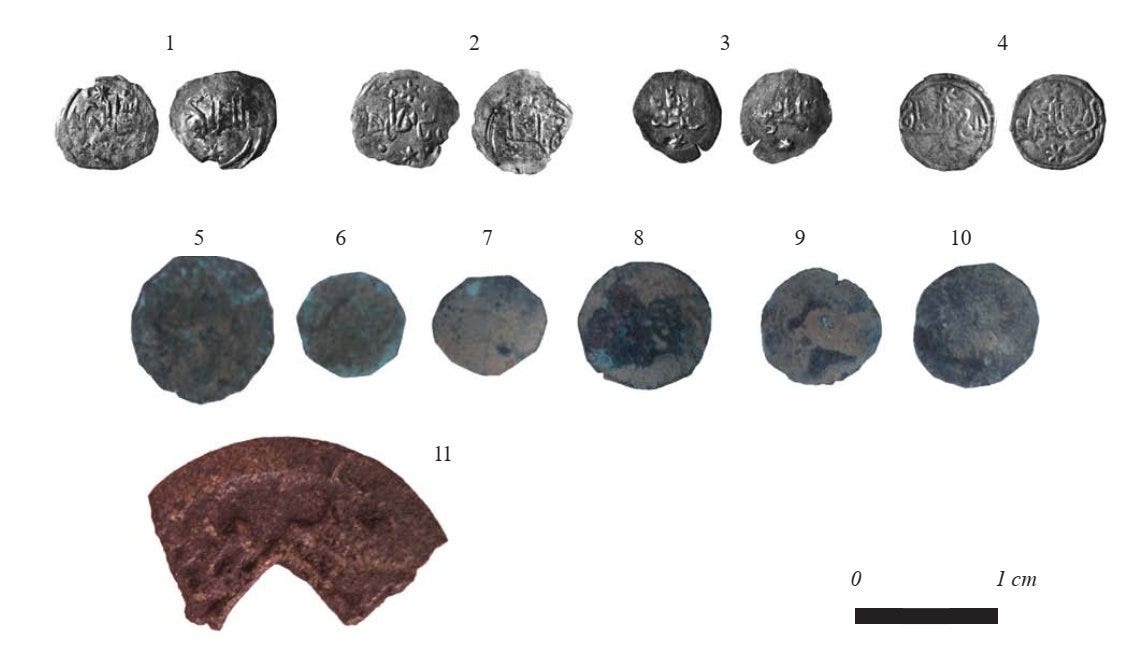

In 1944, a soldier on Australia’s most remote northern coastline discovered a handful of copper coins that were originally minted in the medieval Swahili city of Kilwa, Tanzania, between 1150 and 1330 CE.1

The Kilwa coins are the oldest foreign objects in Australia, and remain the most distant African coins found outside the continent, only rivalled by the collection of Aksumite coins that were discovered in western and southern India.

Two of the five Kilwa coins found on Marchinbar in the Wessel Islands, Australia. Image by Ian S. McIntosh

While the circumstances by which Kilwa’s copper coins were taken so far away from the East African coast are still debated, there is growing historical evidence for East African travellers and sailors across the Indian Ocean World since late antiquity.

These Africans who travelled on their own volition were of varying status, including merchants and pilgrims who visited the Persian Gulf, Arabia, and India, and the multiple envoys from several East African kingdoms who reached China during the Middle Ages.

Some of these adventurous explorers relied on established networks of other Africans across the diaspora to facilitate their international activities, while the foreign journeys of other Africans were at times fully financed by their guests.

In the year 1071 CE, an envoy from the East African island of Cengtan (層檀, ie, Zangistân/Zanzibar in Tanzania) named Cengjiani visited the court of the Song dynasty ruler Shenzong (r. 1067–85):

“Traveling by sea, with the favorable [monsoon] winds, the envoy took 160 days. Sailing by way of Wuxun [near Muscat, Oman], Kollam [in India], and Palembang [in Indonesia], he arrived at Guangzhou.

In 1083, the envoy Protector Commandant Cengjiani 層伽尼 came [to China] again [bearing gifts] to court. [Our emperor] Shenzong 神宗 [r. 1067–85], recognizing the extreme distance he had traveled in returning, beyond presenting him with the same gifts as before, added 2,000 taels of silver”2

This account, contained in the official chronicle known as ‘The History of Song,’ indicates that the East African envoy travelled along a well-established sea route that would be used by multiple East African sailors in the Indian Ocean, especially those who visited India during the Portuguese period.

Silver coins found at Unguja Ukuu, Zanzibar, Tanzania. All were issued by local rulers in the 11th century, except the large coin at the bottom (No. 11), which is a 12th-century Chinese coin.

Accounts from the 17th and 18th centuries indicate that African travellers cultivated commercial, political, and matrimonial alliances across the Indian Ocean world, thus creating African diasporic networks that facilitated their international movement.

One particularly well-travelled character was Mwinyi Ahmed (Bwana Kibai), an important 18th-century Swahili nobleman who played a central role in the brief expulsion of both the Omanis and Portuguese from the East African coast between 1724 and 1730.

Mwinyi Ahmed initially served as the governor of Mombasa (Kenya) under the Omanis after the latter had forced the Portuguese out of Fort Jesus in 1698, but he later fell out of favour with his suzerains. Hoping to expel the Omanis from the coast, Mwinyi Ahmed travelled to Pate (in Kenya), and then to Barawa (Somalia), from where he took a ship to Surat (India) in 1724, where he met the Portuguese and offered to form an alliance against the Omanis by presenting himself as an envoy of Pate.3

Mwinyi Ahmed then moved to Goa in 1725, where he stayed with another Swahili resident in India, Bwana Dau of Faza, because he had been discredited by the ruler of Pate, who informed the Portuguese governor of Goa that Mwinyi Ahmed wasn’t an envoy of Pate. It wasn't until late 1727 that Mwinyi Ahmed and Bwana Dau returned to Mombasa with a Portuguese fleet, having convinced the new governor of Goa, whose forces proceeded to reoccupy Fort Jesus.

But the Portuguese re-occupation was short-lived, as Mwinyi Ahmed turned on his erstwhile allies, besieged Fort Jesus in 1729, and provided his defeated foes with boats to sail back to Goa. He then organised an embassy to travel to Oman and negotiate on his own terms.4

Fort Jesus, Mombasa, Kenya. Image by World History Encyclopedia

Mwinyi Ahmed's career shows that East Africans were familiar with the political landscape of the Indian Ocean world and regularly travelled between its major port cities, often relying on African diasporic communities and local authorities to facilitate their journeys.

This African tradition of international movement is exemplified by the careers of two East African globe-trotters from Anjouan (Comoros) and Somalia who travelled across Asia, Europe, and the Americas during the mid-19th and early 20th centuries.

The two figures, Abdullah Alawi of Anjoan, and Ibrahim Ismaa’il of Somalia, left a rich documentary record of their journeys between India, Oman, Yemen, France, Britain, and the United States. Their contrasting experiences across the four continents were shaped by the extent to which local authorities and established communities of Africans in the diaspora aided or impeded their journeys.

The travel accounts of the two East African globetrotters and their contrasting experiences are the subject of my latest Patreon article:

Please subscribe to read more about it here and support this newsletter:

Australia’s Kilwa Coins Conundrum by Ian S. McIntosh, in ‘Early Maritime Cultures in East Africa and the Western Indian Ocean,’ edited by Akshay Sarathi. The Indian Ocean and Swahili Coast coins, international networks, and local developments by J Perkins. Life and Death on the Wessel Islands: The Case of Australia’s Mysterious African Coin Cache by Ian S. McIntosh

Two Thousand Years of Sino-African Relations by Shen Fuwei, pg 262, Slavery in East Asia by Don J. Wyatt, Swahili Origins: Swahili Culture by J. de V. Allen, pg 186, 146, The Swahili World by Stephanie Wynne-Jones, pg 372

Les cités - États swahili de l'archipel de Lamu by Thomas Vernet pg 420-421, The Portuguese period in east africa by Justus Strandes pg 242

Les cités - États swahili de l'archipel de Lamu by Thomas Vernet pg 422-435, 445, 452, The Portuguese period in east africa by Justus Strandes pg 253-255

Wow how inspiring and fascinating to know just how far and wide our people have travelled the world against the odds 👏🏾🙏🏾🖤

Strange how the Kilwa coins remain little discussed—aren’t they some of the clearest material traces of East African global reach in the early medieval period?