The African diaspora in Portuguese India: 1500-1800.

Sailors, Merchants and Priests.

The Indian sub-continent has historically been home to one of Africa's best documented diasporic communities in Asia. For many centuries, Africans from different parts of eastern Africa travelled to and settled in the various kingdoms and communities across India. Some rose to prominent positions, becoming rulers and administrators, while others were generals, soldiers and royal attendants.

The arrival of the Portuguese in the Indian ocean world in 1498 was a major turning point in the history of the African diaspora in India. Political and commercial alliances were re-oriented, initiating a dynamic period of cultural exchanges, trade and travel by Africans. Sailors and merchants from the Swahili coast, royals from the Mutapa kingdom, and crewmen from Ethiopia established communities across the various cities of the western Indian coast who joined the pre-existing African diaspora on the subcontinent.

This article explores the history of the African diaspora in Portuguese India from the 16th to the 18th century, focusing on Africans who travelled to India out of their own volition, and eventually resided there permanently.

Map showing the cities and kingdoms of the western Indian Ocean mentioned below1

Support African History Extra by becoming a member of our Patreon community, subscribe here to read more on African history and keep this newsletter free for all:

Background on the Swahili city-states, the Portuguese and the western India coast at the turn of the 16th century.

The earliest African diaspora in Portuguese India was closely associated with the Portuguese arrival in the western Indian ocean. When the ships of Vasco Dagama rounded the cape and landed on Mozambique-island in 1498, the rivaling Swahili city-states were alerted to the presence of a new player in the coast’s factious political environment.

Malindi quickly took advantage of the Portuguese presence to overpower its rival, Mombasa. Malindi’s sultan hosted Vasco Da gama, whose hostile encounter at Mozambique-island and Mombasa had earned him a bad reputation among many of the Swahili elites. Malindi boasted a cosmopolitan population that included not just the Swahili and other African groups, but also itinerant Indian and Arab merchants. Among these was an experienced sea-captain named Malema Cana who agreed to direct the Portuguese crew to the Indian city of Calicut. Later Portuguese expeditions would eventually battle with the rulers of Calicut and Goa, seizing both by 1510 and making Goa the capital of their possessions in the Indian ocean. In the suceeding decades, a number of Indian cities would fall under Portuguese control including Diu, Daman, Surat, Bassein, Bombay, and Mangalore.2

On the East African coast, a similar pattern of warfare led to the capitulation of Mombasa, Kilwa, Zanzibar, Mozambique island, and Sofala to the Portuguese over the course of the 16th century. Malindi leveraged its alliance with the Portuguese to become the capital of the Portuguese posessions on the east African coast and thus the seat of the “captain of the coast of Malindi”. Like many of the large Swahili cities, the merchants of Malindi were engaged in trade with the Indian ocean world, primarily in ivory and gold —a lucrative trade which continued after the Portuguese occupation of Goa.3

ruins of Old town, Malindi

Swahili voyages to Portuguese India: trading expeditions of Sultans and Merchants.

Prior to the Portuguese arrival, Swahili traders had been carrying goods on locally-built mtepe ships and on foreign ships to the coasts of Arabia, India and south-east Asia as far as the city of Malacca4. This trade continued after the Portuguese ascendancy but was re-oriented. The Malindi sultan thus pressed his advantage, as early as 1517, by sending a letter to his suzerain, the king of Portugal, requesting a letter of protection to allow him free travel in his own ship throughout the Portuguese possessions from al-Hind (India) to Sofala (Mozambique). This was the first of several requests of safe passage made on behalf of Swahili sailors who were active in Portuguese India.5

There are similar letters from the late 16th century of a Malindi sultan, king Muhammad, sending a ship to the Portuguese settlement of Bassein (India) in 1586, as well as to Goa during the same year to warn the Portuguese about the Ottoman incursion of Abi Bey who had allied with some Swahili towns led by Mombasa and Pate. And around the year 1596, the same Malindi sultan wrote to Philip II of Spain, asking that his ships should sail freely throughout the Iberian possessions in India without paying taxes, He also asked for the free passage for a Malindi trading mission to China (likely, to Macau), to improve his finances. These requests were granted, the latter in particular may have been a consequence of the decline in Malindi's trade during the late 16th century and the eventual shift of the Portuguese administration of east Africa to Mombasa in 1593.6

Such requests of safe passage and duty free trade also taken up by private merchants who sailed on their own ships to India. For example the Mozambique-island resident named Sharif Muhammad Al-Alawi, who passed on the 1517 Malindi letter to the Portuguese, also requested a letter of safe passage for his own ship. Several later accounts mention East African merchants sailing regulary to India. An account from 1615 mentions a Mogadishu born Mwalimu Ibrahim who is described as an expert in navigation from “Mogadishu to the Gulf of Cambay”, his brother was involved in Portuguese naval wars off the coast of Daman. While another 1619 account mentions itinerant traders from the Malindi coast visiting Goa regulary, including a trader from Pate named Muhammad Mshuti Mapengo who was “well-known in Goa, where he often goes.”7

Letters by the Malindi sultan and the Mozambique merchant Muhammad Al-Alawi, adressed to the Portuguese king Manuel, Arquivo Nacional da Torre do Tombo

Swahili voyages to Portuguese India: Envoys and Political alliances.

The activities of the Swahili elites in Portuguese India were partly dependent on their city's political relationship with local Portuguese authorities. When the Portuguese captured Mombasa in 1593, a more complex relationship was developed with the Swahili cities both within their direct control such as Mombasa, Pemba and Malindi, and those outside it such as Pate. Regular travel by Swahili elites to India were undertaken in the early 17th century as the nature of Portuguese control was continously re-negotiated. This was especially the case for the few rulers who adopted Catholism and entered matrimonial alliances with the Portuguese such as the brother of the king of Pemba who in the 1590s travelled to Goa but refused the offer to be installed as king of Pemba.8

A better known example was the sending of the Mombasa Prince Yusuf ibn al-Hasan to Goa in 1614 after a power struggle with the Portuguese governor at Mombasa had ended the assassination of his father. The prince was raised by the ‘Augustinian order’ in Goa where he was baptized as Don Jeronimo Chingulia. While in Goa, he married locally (albeit to a Portuguese woman) and was active in the Portuguese navy, before he was later crowned king of Mombasa in 1626 in preparation for his travel back to his home the same year. He would be the first of many African royals who temporarily or permanently resided in Goa, among whom included his cousin from Malindi named Dom Antonio.9

Swahili factions allied with the Portuguese often travelled to Goa and some lived there permanently. These include Bwana Dau bin Bwana Shaka of Faza, a fervent supporter of the Portuguese who settled in Goa after 1698 and kept close ties with the administration. In 1724, Mwinyi Ahmed Hasani Kipai, an ambitious character from Pate, took a ship in Barawa to meet the Portuguese in Surat and later on in Goa.10

In 1606, two Franciscan friars met a mwalimu (ship pilot) from Pemba whom they described as a Swahili "old Muslim negro", that in 1597 had guided the ship of Francisco da Gama, the future viceroy of India, from Mombasa to Goa. Others included emissaries who travelled to Goa on behalf of their sultans, such include the Mombasa envoys Mwinyi Zago and Faki Ali wa Mwinyi Matano, that reached Goa in 1661 and 1694 respectively.11

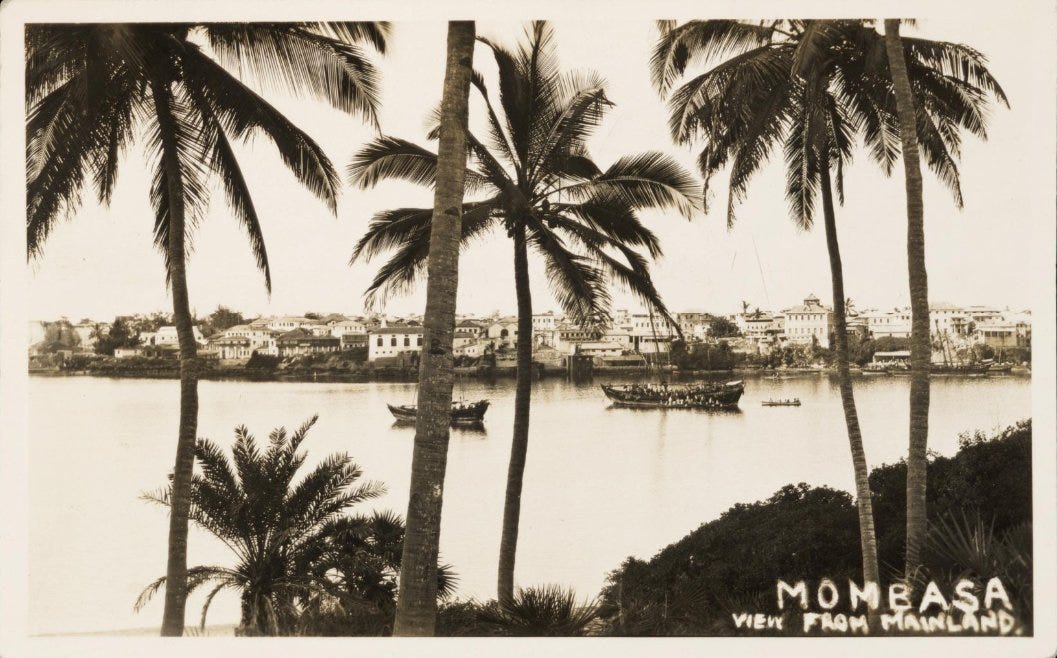

Mombasa beachfront, ca. 1890, Northwestern University

Mutapa priests in India: royal Africans of the Dominican order.

Contemporaneous with the Portuguese presence on the east African coast was their expansion into the interior of south east Africa, especially in the kingdom of Mutapa in what is now Zimbabwe. From the early 17th century when the Portuguese were extending their control into parts of this region, members of the royal courts who allied with the Portuguese and adopted Catholicism often travelled to Goa and Lisbon for religious studies. These travels were primarily facilitated by the ‘Dominican order of preachers’, a catholic order that was active in the Mutapa capital and the region's trading towns, establishing religious schools whose students also included Mutapa princes. Unlike the itinerant nature of the Swahili presence in India, the presence of elites from Mutapa in India was a relatively permanent phenomenon.12.

Among the first of Mutapa princes to be sent to India was Dom Diogo, son of the Mutapa king Gatsi Rucere, he was sent to Goa in 1617 for further education by the Dominican prior, with the hope that he might suceed his ageing father. However, Dom Diogo died a few years after his arrival in Goa, becoming the first of the Mutapa elites who remained in Portuguese India. He had likely been accompanied to Goa by a little-known prince who later converted and became a priest named Luiz de Esprito Santo. This priest would later return to Mutapa to proselytize but died in the sucession wars after king Gatsi’s death.13

He was soon followed by other Mutapa princes including Miguel da Presentacao, son of Gatsi's sucessor, king Kapararidze. Miguel spent most of his life in Goa from May 1629, where he would be educated and later earn a degree in theology. The young prince also travelled to Lisbon in 1630, where he received a Dominican habit and accepted into the order as a frair. The unusual circumstances in which this young old African prince was accepted into the order was likely due to royal intervention.14

Miguel returned to Goa in 1633 and was ordained as a priest, serving in the Santa Barbara priory in Goa, teaching theology and acting as a vicar of the Santa Barbara parish. In 1650, the Portuguese king requested that he return to Mutapa to suceed king Mahvura but Miguel chose to stay in Goa, where he would later be awarded the title master of theology in 1670 shortly before his death.15

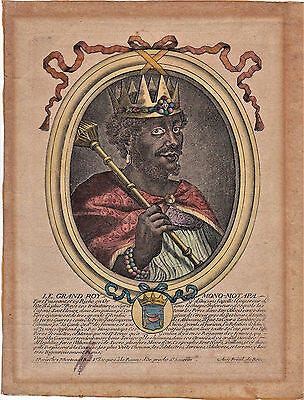

engraving titled; ‘Le grand Roy Mono-Motapa’ by Nicolas de Larmessin I (1655-1680) depicting a catholic king of Mutapa

Two other Mutapa princes were also sent to India at the turn of the 18th century by the Mutapa king Mhande (Dom Pedro). The first of these was Mapeze, who was baptized as Dom Constantino in 1699 and sent to the Santa Barbara priory in Goa the following year. Shortly after, Constantino was joined in Goa by his brother Dom Joao. Both of the princes' studies and stay in India were financed by the Portuguese crown, which influenced the local Dominican order to accept them, with Constantino receiving a Dominican habit. After reportedly committing an indiscretion, Constantino was briefly banished to Macao (in China) by the vicar general of Goa, before the Portuguese king ordered that the prince be returned to Goa in 1709.

When the Mutapa throne was taken by a king opposed to the Portuguese in 1711, the Portuguese king asked Constantino to return to Mutapa and take up the throne, but the later refused, claiming that he had renounced all worldly ambitions, an excuse that the Portuguese accepted. Constatino received a pension from the crown but was in conflict with his local religious superiors, which forced him to request safe passage to Lisbon for him and his brother. Constantino died en route but his brother opted to go to Brazil where he was eventually buried in the cathedral of Bahia.16

More African elites and students were sent to Goa during the 18th century, despite the great decline of the Portuguese presence in Mutapa, Eastern Africa and India. Atleast one Mutapa prince is known to have been sent to Goa around 1737 to enter the Dominican order, but he died shortly after his arrival. In the late 18th century, there were a number of Africans from Mozambique who received training in the Dominican priory at Goa, many of whom remained in India. Unlike the princes, these were youths whose families lived next to the mission stations in Mozambique, atleast 6 of them are known to have been admitted in 1770, but its unknown if they completed their training.17

Establishing an African diaspora in India: the East Africans and Ethiopian community in India.

Besides the itinerant merchants, royals, and priests, the African population of Portuguese India also included the families of merchants, sailors, crewmen, dockworkers and other personalities, all of whom worked in various capacities in the various port cities. Alongside the relatively small numbers of African elites who resided permanently in India, these Africans comprised the bulk of the African diaspora in Portuguese India.

The abovementioned requests for letters of safe passage by Swahili sultans, hint at the predominantly African crew of the ships which sailed to India. Internal Swahili accounts such as the Pate chronicle mention atleast two sultans who organized trading expeditions to India, especially along the Gujarat coast, during the 16th and 17th century. In 1631, a sultan of Pate sent a ship to Goa whose crew mostly consisted of his wazee (councilors/elders of Pate), and in 1729, another sultan of Pate asked of the Portuguese the right to send “one of his ships” loaded with ivory to Diu.18

The African merchants who sailed to India were not all itinerant traders, but included some who stayed for long periods and married locally. In 1726, a letter from the king of Pate cited one Bwana Madi bin Mwalimu Bakar from Pate “who goes each year to Surat where he is married.”19 Matrimonial alliances were a common feature of commercial relationships in the Indian ocean world -including among the Swahili, and it would not have been uncommon for Swahili merchants who travelled to India to have engaged in them and raised families locally.

But the Swahili were not the only African group which permanently resided in Portuguese India. According to Jan Huygen van Linschoten, who lived in Goa in the 1580s, “free Muslim Abyssinians are employed in all India as sailors and crew aboard the trading ships which sail from Goa to China, Japan, Bengal, Malacca, Hormuz and all the corners of the Orient.”

These sailors and often took their family aboard and comprised the bulk of the crew, such that the Portuguese who owned and/or captained the ship were often the minority. Some these African sailors also held high offices, such as in the India city of Dabhol in 1616, where the captain of a large ship was a Muslim “black native” from “Abyssinia”, and a pilot of a Mughal trading ship docked in Goa’s habour in 1586 was an Abyssinian who chided a Portuguese captain for losing to the Ottoman corsair Ali Bey on the Swahili coast.20

The use of the ethnonym “Abyssinians” here is a generic reference to various African groups from the northern Horn of Africa, who had long been active in India ocean trade. While the above references are concerned with Muslim Abyssinians, there are atleast two well known Christian Ethiopians who travelled to India in the early 15th century. They include a well-travelled scholar named Yohannes, who journeyed across much of southern Europe and reached Goa on his return journey in 1526, where he met with another Ethiopian named Sägga Zäab, who was the Ethiopian ambassador to Portugal21.

Yohannes' travels to Europe and India. Map by Matteo Salvadore

Right Street in the City of Goa, Portuguese India, between 1579 and 1592. by Jan Huygen van Linschoten. The painting includes African figures.

Many Christian Ethiopians also reached Portuguese India during the period when the two nations were closely allied against the Ottomans. These Ethiopians not only travelled for trade but for permanent settlement, the latter of which was often sponsored by the Portuguese. For example in the 1550s, the viceroy Dom Constantino de Braganca granted villages in the Daman district to Christian Abyssinians. This community proved quite sucessful and produced prominent benefactors for the local Jesuit missions such as one named catholic Ethiopian named Ambrosio Lopes, who left a significant fortune for the Jesuit church in Bassein22. Another is the ‘Abyssinian Christian matron’ named Catharina de Frao, who proselytized among local Muslim and Hindu women.23

As a testament to the dynamic nature of the African diaspora in Portuguese India, the resident ‘Abyssinian’ community of India, called the Siddis, who had arrived to the subcontinent some centuries before the Portuguese, was attimes involved in conflict with the latter, who were themsleves supported by other Ethiopians. Before the abovementioned viceroy Constantino De Braganca acquired Daman in 1558, he had to battle with the forces of a siddi named Bofeta, who was incharge of the city’s garrison comprised of mixed Turkish and Ethiopian soldiers. And the city of Diu was itself guarded by a force comprised mostly of Siddis before it was taken by the Portuguese in 1530 24

The African community in Portuguese India therefore occupied all levels of the social hierachy; from transient envoys and merchants to resident royals, priests, soldiers, sailors and crewmen. This community was borne out of the complex political and commercial exchanges between Africa and India during the era of Portuguese ascendance in the Indian ocean, and was part of the broader patterns of cultural exchange that eventually saw Africans arriving on the shores of Japan in 1543.

detail of a 17th century Japanese painting, showing an African figure watching a group of Europeans, south-Asians and Africans unloading merchandise.

READ more about the African diaspora in 16th century Japan here:

Around 3,5000 years ago, a complex culture emerged in the region of central Nigeria that produced Africa’s second largest collection of sculptural art during antiquity, as well as the earliest evidence for iron smelting in west Africa

READ about it here:

Map by Thomas Vernet

Empires of the monsoon: A history of the Indian Ocean and its invaders by Richard Seymour pg 163-178)

Les cités-États swahili de l'archipel de Lamu by Thomas Vernet pg 81-82)

The Suma oriental of Tome Pires by Tomé Pires pg 46, A Handful of Swahili Coast Letters, 1500–1520 by Sanjay Subrahmanyam pg 270

East African Travelers and Traders in the Indian Ocean by Thomas Vernet 169-170 pg 167-169, Les cités-États swahili de l'archipel de Lamu by Thomas Vernet pg 101

East African Travelers and Traders in the Indian Ocean by Thomas Vernet pg 180, 184-185, Les cités-États swahili de l'archipel de Lamu by Thomas Vernet pg 143)

Identidade pessoal, reconhecimento social e assimilação: a inclusão de membros de famílias reais africanas e asiáticas na nobreza portuguesa by Manuel Lobato pg 123-124, Les cités-États swahili de l'archipel de Lamu by Thomas Vernet pg 194

The Swahili Coast, 2nd to 19th Centuries, by G. S. P. Freeman-Grenville pg 94, The Church in Africa 1450-1950 by Adrian Hastings pg 128, Identidade pessoal, reconhecimento social e assimilação by Manuel Lobato pg 125-126

East African Travelers and Traders in the Indian Ocean by Thomas Vernet pg 189)

East African Travelers and Traders in the Indian Ocean by Thomas Vernet pg 184)

The Church in Africa 1450-1950 by Adrian Hastings, 120-121)

The Dominican Friars in Southern Africa: A Social History (1577-1990) By Philippe Denis pg 19-20, Iberians and African Clergy in Southern Africa by Paul H. Gundani pg 183-184

Iberians and African Clergy in Southern Africa by Paul H. Gundani pg 180-181

The Dominican Friars in Southern Africa: A Social History (1577-1990) By Philippe Denis pg 31-33)

The Dominican Friars in Southern Africa: A Social History (1577-1990) By Philippe Denis 42-44)

The Dominican Friars in Southern Africa: A Social History (1577-1990) By Philippe Denis pg 49, 61)

Les cités-États swahili de l'archipel de Lamu by Thomas Vernet pg 151, 153)

Les cités-États swahili de l'archipel de Lamu by Thomas Vernet pg 152)

East African Travelers and Traders in the Indian Ocean by Thomas Vernet pg 185, The Ottoman Age of Exploration By Giancarlo Casale pg 167

African cosmopolitanism in the early modern Mediterranean by M. Salvadore pg 68-69

The Portuguese in India and Other Studies, 1500-1700 By A.R. Disney, The History of the Diocese of Damaun by Manoel Francis X. D'Sa pg 46

History of Christianity in India: From the middle of the sixteenth to the end of the seventeenth century, 1542-1700 by Church History Association of India, pg 321

Indian Ocean and Cultural Interaction, A.D. 1400-1800 by Kuzhippalli Skaria Mathew pg 37

This is fascinating history. Very informative. Thanks

Amazing. Quite interesting reading about Mutapan princes eschewing royal power for a quiet life amongst the Dominicans, don't know if it was sincerely out of belief or they were simply tired of courtly intrigue (hahaha).

Also, where do you source your images? I've found that a lot are either buried in textbooks or behind a paywall.