An African kingdom's existential war against the British colonial empire: the Anglo-Bunyoro wars (1872-1899)

A little-known extermination campaign by colonial armies in East-Africa

For nearly 30 years, some of the most ferocious British colonial wars in the world occurred in the kingdom of Bunyoro in western Uganda, they involved dozens of invasions by tens of thousands of soldiers armed with the most destructive modern weapons, conducting severe extermination campaigns that were nearly as brutal as those carried out by the Germans in Namibia and French in Algeria.

While Bunyoro, like the other centuries-old kingdoms of the 'Great Lakes' region of eastern Africa, had only recently extended its commercial reach into the global markets, Its institutions proved adaptive enough to be quickly adjusted in response to the rapidly changing international political landscape of imperial expansion in which the kingdom was thrust; enabling Bunyoro to sustain one of the longest defensive wars against colonialism.

This article explores the history of Bunyoro from its establishment in the 15th century to its existential war for survival against the onslaught of British colonial expansion in the late 19th century.

A collapsed time-scale map showing the major invasions of the Bunyoro kingdom by year and the British commanding officers leading them.

Support African History Extra by becoming a member of our Patreon community, subscribe here to read more about African history, download free books, and keep this newsletter free for all:

The establishment of the Bunyoro kingdom: a reinterpretation of “kitara”

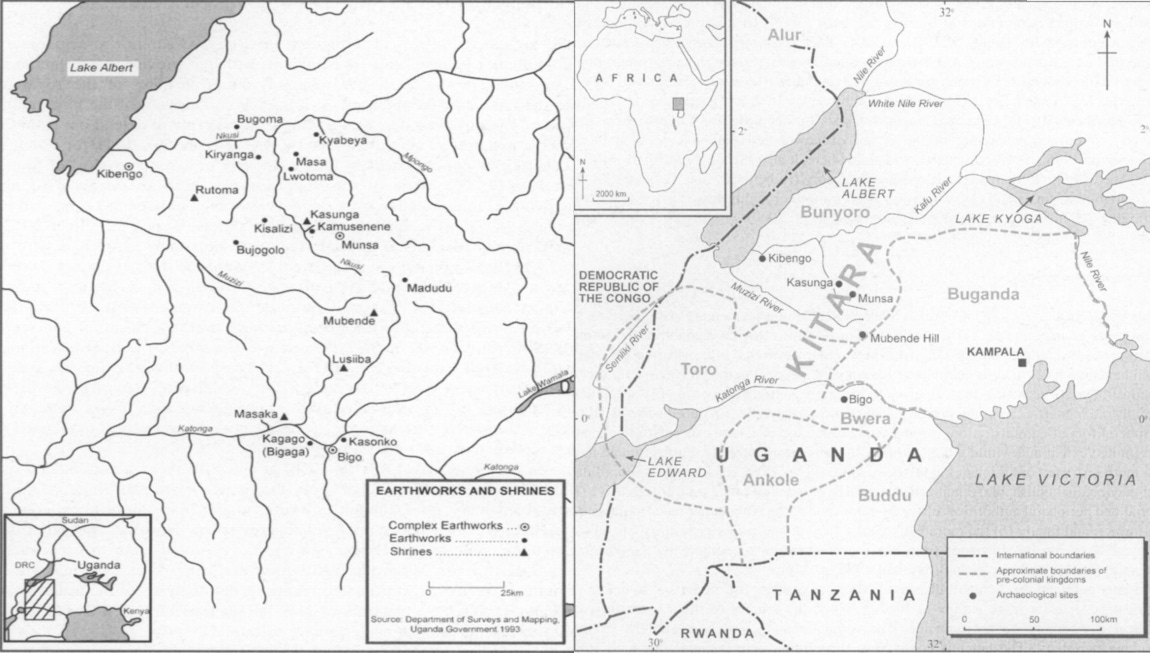

One of the recurring themes about the early history of the Great-lakes kingdoms is the political concept of “Kitara”, a semi-legendary 'empire' which controlled a vast territory extending from the western shores of lake albert, eastwards to lake Victoria and southwards to lake kivu.1 The Kitara state's semi-legendary Chwezi dynasty were later claimed to have constructed the monumental earthworks of the ‘iron-age’ sites across western Uganda, and their associated hill-top religious centers, and are said to have been deposed by the Bito dynasty who retained the core of the fragmented empire as the Bunyoro kingdom, while other splinter dynasties established the various kingdoms of Buganda, Nkore, Nyiginya (rwanda), Karagwe, etc.2

This interpretation of the region’s history was popular in the early 20th century, was based on uncritical analysis of oral history and 19th century accounts, as well as the political exigencies of the colonial era, but it has since been discredited as simplistic, after it was discovered to contradict with recent archeological research and more critical analysis of oral and documented history3. The traditions about the so-called Chwezi dynasty were subverted by subsequent rulers of the Great-lakes kingdoms to provide symbolic sanction for their own authority, and the identification of the monumental earthworks as Chewzi sites was a 20th century invention created in the accounts of writers that were external to the region4. The over-emphasized role of a "foreign-founder" pastoral elite can be safely disregarded as a recent invention influenced by the Hamitic race myth of colonial historiography5, since hierarchical centralized states were largely absent among the pastoral groups in the regions immediately outside the Great-lakes region where the southern elites are supposed to have emerged,6 and the archeological evidence of a mixed agro-pastoral economy within the elite settlements at the iron-age sites contradicts any claim of a singularly pastoral elite.7

Combining archeological evidence with history traditions reveals a more coherent picture about the political structure of the incipient states of the Great-lakes region; revealing early states in which rulers performed several roles, including political leadership of smaller-scale polities founded at the iron-age sites of Munsa, Ntusi, Bigo, Kibengo (9th-17th century)8, control of production of salt (eg from kibiro 11th century-), as well as iron, cloth and the accumulation of wealth in cattle plus some long distance trade goods eg copper, ivory9, and the promulgation of several religious cults on the hill-top sites of Mubende and Kasunga (14th century) ; all of which were features that were transmitted across the region, hence their preservation in many history traditions across all the Great-lakes kingdoms including the Bunyoro kingdom.10

Map of showing the iron-age sites, the location of the Bunyoro kingdom’s core and the semi-legendary Kitara heartland.11

The Political history of the Bunyoro kingdom: expansion and consolidation (15th-18th century)

The kingdom of Bunyoro was established in the 15th century around the time the iron-age sites were abandoned12. The kingdom held a significant demographic and resource advantage over its later peers; the territory it controlled had long been a magnet for concentrating populations (necessary for producing agricultural surpluses and raising armies)13, it possessed rich sources of salt for long distance trade (eg at Katwe and Kibiro, the latter of which was a town with a population of 6,000-10,000 in the late 19th century14), as well as iron ore which was necessary for agricultural tools and weaponry.15

The emergence of Bunyoro as a large, territorial kingdom that subsumed the smaller incipient states, altered the political equilibrium in the region, and its hegemony was counter-balanced by the emergence of other polities on Bunyoro's southern and eastern fringes who were by then constituting themselves into kingdoms.16 From the reign of the Bunyoro King (Omukama) Olimi I (r.1517-1544) down to Olimi III (r.1733-1760), the kingdom expanded and consolidated its power across the region; eastwards against Buganda during the reign of Olimi I, northwards against the Madi during the reign of Nyabongo (r.1544-1571), southwards against Nkore and Rwanda during the reign of Chwa I (r.1626-1652). 17

Map of the Great-Lakes kingdoms in the 18th century

The best evidence for Bunyoro's regional hegemony in the not so distant past comes from the historical traditions of its southern neighbors —a region which the Bunyoro courtiers who met explorer J.H Speke in 1862— claimed was once part of their vast state whose influence extended upto the Kagera river in Rwanda. Traditions of the kingdoms of Nkore (south-western Uganda), Karagwe (in north-western Tanzania) and Nyiginya (in Rwanda) all recall wars with Bunyoro’s armies in the 16th-17th century which were repelled by kings who took the title of Nyoro-slayer (kiitabanyoro), and their enemy forces’ leaders often have Nyoro royal names and ethnonyms (especially Chwa).18

As for its eastern expansion, Bunyoro’s king Kamurasi (r.1851-1878) told the explorer Samuel Baker in 1866 that Buganda had been a dependent province until the early 19th century. While this story was mostly a deliberate fabrication by Kamurasi since Buganda had defeated Bunyoro in the late 18th century leading to King Duhaga's death in 1782, it had also annexed Bunyoro’s client state of Buddu, and installed an ally in the breakaway province of Toro, but Kamurasi's story nevertheless referenced a real historical relationship during the not-so-distant past when Bunyoro wielded significant political power over the early Buganda kingdom. This is also evidenced by the appearance of Bunyoro in Buganda's early political history, as well as the early Buganda ruler Chwa who precedes king (kabaka) Kimera, the founder of the ruling dynasty of Buganda, and who is himself said to have been raised in the Bunyoro court and brought with him some of its regalia and institutions.19

Bunyoro in the 18th and 19th century was a large centralized kingdom that was organized with a similar (but not entirely identical) structure as medieval feudal states. The ultimate political authority was the King (omukama) who was subordinated by provincial rulers (abakama b’obuhanga) and lesser chiefs, who received grants of estates from the king and were expected to collect tribute for the king, provide military levies and corvée labor. The provincial rulers and chiefs were also resident in the capital for elaborate ceremonies (such as the new-moon ceremony) and occasionally accompanied the king during his tour of the kingdom, staying within his mobile or ”moving” capitals.20 The king was assisted by a hierarchy of officials especially councilors (abakuru b’ebitebe) who influenced the choice of provincial rulers, and were part of the governing body or "parliament" of the kingdom (orukurato orukuru rw’ihanga).21

Bunyoro’s new moon ceremony, king Andereya (r. 1902-1924) advancing along the sacred pathway, c. 1919, John Roscoe

building for Bunyoro’s “parliament” (foreground) and the King’s residence (background), Masindi, c. 1919, John Roscoe

Bunyoro under king Kabalega and the first colonial invasion

The quasi-feudal structure of the Bunyoro kingdom encouraged the emergence of an intermediate class of titled officials and aristocrats and the dispersion of royal claimants across a much broader section of society, which served to increase succession conflicts led by rebellious princes.22 When king Kamurasi died in 1869, a bitter succession war engulfed the kingdom, fought between the rival claimants Kabigumire, Ruyonga, and Kabalega; with the Kabigumire soliciting support from Nkore, Ruyonga soliciting support from Ottoman-Egypt in the north, while Kabalega solicited support from Buganda's king Mutesa, the latter of whom ultimately secured Kabalega's installation in 1871, while Kabigumire was eventually defeated and killed, as Ruyonga fled north of Bunyoro.23

The involvement of Ottoman-Egypt in Bunyoro's succession wars increased the resolve of its sultan; Khedive Ismāʿīl (r. 1863-1879), to colonize the kingdom by employing the services of the British (and other European powers) to whom he was deeply indebted, and was desperately looking for more resources to pay them back24. Ismail chose Samuel Baker --the above-mentioned explorer who had been treated to a cold reception in Bunyoro during his first visit 1866-- to be OttomanEgypt's governor of equatoria colony (southern Sudan) in 1869. Baker was tasked to extend the then "Anglo-Egyptian" empire and (ostensibly) to stop slave trade; both of which tasks he claimed success but with little justification25, as the evidenced by the disintegration of the Bari-land's political structures (Bari was directly north of Bunyoro), and the incessant rebellions and devastation of the region during his governorship (1869-74) and that of his successors; Charles Gordon (1874-1876) and Emin Pasha (1876-1888)26. Samuel Baker's overt prejudice against Bunyoro as recorded in his accounts about the kingdom reflected not just his background as a son of a west-Indian slave owner, but also his belief in polygenism (about the separate genesis of "races"), both of which give him a habit of exaggerating cultural differences inorder to justify his imperialist argument for "enlightened governance".27

Baker arrived at Kabalega's capital of Masindi in 1872 with an armed expedition of 1,000 of which about 120 were soldiers, and while his intention was to annex Bunyoro, Kabalega's hope was that Baker could support his war against Rionga. Baker's poor diplomatic skills turned Kabalega's initially positive attitude against him especially after the former refused to assist Kabalega, but chose to raise the Ottoman-Egyptian flag at Masindi in an absurd ceremony declaring Bunyoro its colony. After a series of clashes between Baker's army and Kabalega's bodyguard, both sides descended into war that ended with Masindi's burning, while Baker retreated with his army and flag, barely able to survive the repeated ambushes by Kabalega's army who inflicted significant causalities.28

Baker's hyperbolic bluster that masked his humiliating retreat from Bunyoro was celebrated in the British press, but the Khedive Ismāʿīl knew that the expedition was a failure, writing that "the success of the expedition has been much exaggerated" and that Baker, had been "too prone to fighting giving rise to a general feeling of hostility towards Europeans and my government in Upper Egypt".29 The Khedive's failure in Bunyoro was a prelude to his monumental defeat by the Ethiopians at Gura in 1876, which fueled the 1881 Mahdist uprising in Sudan that expelled the Ottoman-Egyptians, and ultimately lead to Egypt's formal colonization by Britain in 1882. (see this article below)

Under Kabalega, Bunyoro underwent an institutional transformation that underpinned its economic and military revival, iron production was rapidly increased to supply the expanding northern markets, ivory trade was expanded to acquire more firearms (with one provincial ruler giving 1,800 loads of ivory as tribute), and a direct route to Zanzibar was secured through the southern kingdom of Nkore30. Bunyoro's quasi-feudal army was largely replaced by a permanent army of 12 regiments (known as the abarusura), armed with about 2,000 rifles by the 1889 and supported by the regular army 10-20,000 spearmen. The abarusura were created by reconstituting king Kamurasi's bodyguard of the same name, some of their regiments were then garrisoned in Kabalega's capital as a police force (babbogora). This army's formation influenced the creation of similar standing armies of rifle-men that supported regular armies in Buganda (kijasi) and Nkore (abagonya).31

With this army, Kabalega gradually retook Toro and Busongora (in the south), as well as Chope and Bugungu (in the north) between 1876-1889, he also shifted the balance of power away from Buganda which was then under king Mwanga (r. 1884-8, 1889-97), especially after he defeated a large force from the latter in 1886 at Rwengabi. Following this victory, Kabalega moved to influence Buganda's internal politics during the latter's civil wars in 1889 by supporting the short-lived king Kalema, before Mwanga sought British support for his reinstallation; effectively becoming a colony in December 1890.32

An existential war for survival: the Anglo-Bunyoro wars (1891-1899).

Despite Baker's failed ambitions in Bunyoro, he had established a relationship with the rebellious prince Ruyonga in the north-east of Bunyoro, which, added to Buganda's king Mutesa's (r 1852-1888) resentment over Kabalega's ungratefulness, led to the establishment of direct communication between Buganda and the Anglo-Egyptians in the north, but also with the "Anglo-Zanzibar" sultanate on the east African coast which had been sending commercial expeditions to Buganda, and was also coming under British control33. Buganda's king Mutesa's shrewd diplomatic skills oscillated between perceiving Kabalega as a threat, and successfully averting another Bunyoro invasion by the Anglo-Egyptians in 1876 when he deceitfully trapped their forces at Buganda's capital inorder to preserve Kabalega's kingdom as a buffer. But the politico-religious civil wars under his successor Mwanga's reign that involved all these foreign elements eventually led to the abovementioned vassalage of Buganda to the British under the infamous Lord Lugard.34

In 1891, Bunyoro's allies in Buganda, who had been expelled after Mwanga's reinstallation by Lugard, were decisively defeated by a combined army of 25,000 from Buganda (with 5,000 riflemen, 600 of who were under Lugard), against an army of less than 5,000 (1,300 of whom were abarusura riflemen), marking the start of war between the 'Anglo-Buganda' kingdom and Bunyoro. Lugard then supported a deposed prince of Toro to retake the kingdom from Bunyoro and constructed a line of temporary forts in Bunyoro’s south-western flank that managed to repel dozens of sieges and attacks from Bunyoro from August-November 1891, but the tide of battle turned in Kabalega’s favour by September 1893 following the partial withdrawal of the fort's soldiers, and Toro was briefly retaken by Bunyoro. By November 1893 however, a massive Anglo-Buganda force of 13,000 (with 3,000 riflemen, several maxims and cannon) under the command of British officer Colvile, pursued Kabalega's divided forces (that had been in Toro), and when Kabalega eventually gave battle in August 1894 at Mparo, his army suffered a decisive loss.35

Kabalega soon realized that the constraints his reformed army faced that included; reduced capacity to mobilize large armies, difficulty of procuring modern rifles, slow repaire of old firearms and ammunition shortages, which he weighed against the strength advantages on the British side that had; imposed an arms embargo against him, could outnumber Kabalega's forces using auxiliary troops from Buganda and Sudan that they armed with maxim guns and garrisoned in "forts", and had killed Kabalega's envoys to Mahdist Sudan who had gone to procure more rifles. After having his offer of peace turned down in December 1894 by the British that were bent on total war, Kabalega switched to guerrilla warfare, utilizing his army’s mobility, the use of fortifications and trenches to stall the dozens of British expeditions, and foment rebellions in colonial territories. His resistance was sustained largely because of its wide support across the Bunyoro society and allied chiefdoms.36

“fort Hoima” in 1894 by A.B Thruston, one of the temporary British fortifications, and the headquarters of their main colonial forces.

During the dozens of British colonial invasions from 1891-1899, Bunyoro was systemically depopulated and destocked, due to the demographic disaster that was triggered by the spread of rinderpest and jiggers epidemics introduced by the colonial troops,37 that greatly depleted Bunyoro's manpower38, this was in addition to the kingdom losing 2/3rds of its lands to neighboring kingdoms under British colonial control. Samuel Baker's very prejudiced accounts of Bunyoro had been widely circulated and read by his later peers, and they provoked a strong racial antipathy among the British colonial army officers against Bunyoro kingdom’s subjects, especially after the British realized that the Banyoro didn't perceive them as "liberators" from "barbarous tyranny" of Kabalega. By 1894, this antipathy had degraded into campaigns of ethnic extermination, with British military officers such as Thruston writing (in brazen admission) that it "was the rule to shoot at sight any Wanyoro whom we encountered carrying a gun" and by 1896, the armies of the British under Ternan were in the habit of "randomly murdering Banyoro non-combatants, burning every village and cutting down their banannas".39

Each of these invasions was met with sustained resistance by Kabalega's forces who ambushed retreating British columns, besieged British forts and inflicted a significant causality rate on invading forces.40But Bunyoro's determination to fight was ground down by the sheer brutality of colonial warfare. The primarily intention of Thruston's campaigns was the depopulation of entire provinces, he sent weekly raids in the Bunyoro provinces of katonje and matama that leveled large tracts of farmland and burned thousands of homes until —by Thruston’s own account; "the Banyoro abandoned the area".41 In 1898, one British soldier described the cataclysmic social collapse across the kingdom;

"The time-honoured war with Kabarega had left Unyoro almost a barren waste, and we scarcely saw a native anywhere. With the exception of a few who lived near Masindi, those who had not been exterminated were in arms under their King. The desolation on all sides was most depressing. The little gardens and plantations were rank with weeds and completely deserted, and few wandering natives we met looked half-starved."42

A.B Thruston, H.E. Colville, T.P.B Ternan. Many of the officers who led the Bunyoro invasions attained high ranks solely because of their actions in Bunyoro, because frontier wars offered young officers the kind of positions that couldn't be attained in the main British Army; as Colville commented unpon putting Thruston in charge of Bunyoro's expedition, "it was not every captain of two years who gets an independent command like this"

In April 1898, Kabalega formed an alliance with the deposed Buganda king Mwanga and several thousand of his soldiers who had rebelled against British rule in 1897 and had taken his guerrilla war against the British across the entire region. The British on the other hand, had spent the year reinforcing their colonial troops with more allied Indian, Sudanese, Baganda and Swahili regiments to fight their own mutinous colonial soldiers that, combined with Kabalega and Mwanga's wars, had turned the entire country into a fiery warzone43. By April 1899, frustrated by the British's severe punishments of his subjects for allying with Kabalega, a local chief gave up the position of Kabalega's forces, who were then overwhelmed in a surprise attack by the British that ended with the capture of Kabalega, the last independent Bunyoro king, and effectively ended the kingdom's three decades long war against colonization.44

photo of Omukama Kabalega (2nd from the left) with his family in the Seychelles Islands where he was exiled.

Bunyoro drummers and trumpeters assembling for the new moon ceremony, c. 1919, John Roscoe

Conclusion: Bunyoro and the African response to colonial expansion.

Bunyoro was just one among hundreds of African states whose military strength had for four centuries, successfully kept the colonial armies at bay until the African armies had exploited all the advantages they could gain from their available political and military institutions, relative to the rapidly modernizing armies of industrial Europe. Despite its relative isolation and previous inexperience with modern warfare, Bunyoro rapidly transformed its political and military institutions, enabling it to sustain an extremely bitter existential war in which it was outgunned and outmanned.

While many prefer to imagine the process of colonization as one in which gullible African kings signed away entire nations to shrewd colonial officers, The reality was colonial conquest was a brutal, protracted processes involving total war against entire societies, the decimation of their social institutions, and the advance of disease environments, inorder to exhaust African kingdom’s depleting reservoirs of political goodwill, drain their economic resources that sustain a prolonged war, and ultimately crush their resolve to fight.

While 1899 closed the chapter on the Kingdom’s independence, its resolve to fight continued under colonial rule with the Nyangire anti-colonial rebellion of 1907, and its former subjects continued to play a major role in the political movements that ultimately secured Uganda’s independence.

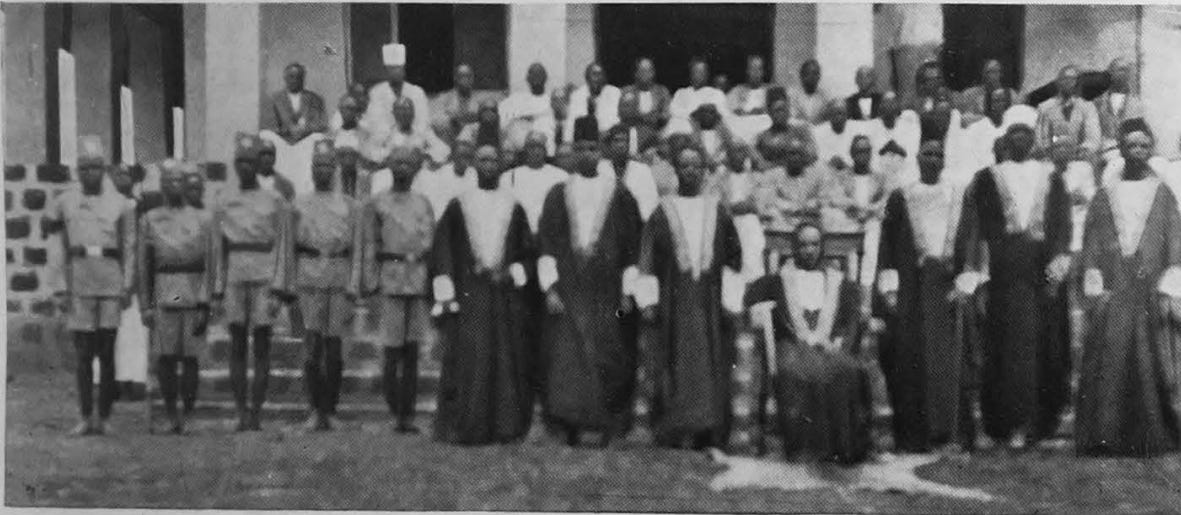

Bunyoro’s King Andereya and courtiers at a wedding, c. 1906, Albert Lloyd, King Andereya and his courtiers and bodyguard, c. 1919, John Roscoe

The HAMITIC MYTH about the FOREIGN origin of African civilizations is a pervasive concept in African historiography including in the history of Bunyoro, But it wasn’t alien product of colonial imposition, it was instead an intellectual conglomeration of both African and European versions of the Hamitic myths.

Read about the interpretation of the BYZANTINE-ARAB ORIGIN myth of west-Africa’s FULANI ethnic group; and AFRICA’S HAMITIC MYTH on my Patreon

Incase you haven’t seen some of my posts in your email inbox, please check your “promotions” tab, move the email to your “primary” tab and click “accept for future messages”.

The Study of the State by Henri J. Claessen pg 354)

The Antecedents of the Interlacustrine Kingdoms by J. E. G. Sutton pg 39-41, 63)

The Ancient Earthworks of Western Uganda by Peter Robertshaw pg 27-28)

Beyond the Segmentary State by Peter Robertshaw pg 259)

The great lakes of Africa by Jean-Pierre Chrétien pg 103-104

Kingship and State By Christopher Wrigley pg 201, The Ancient Earthworks of Western Uganda by Peter Robertshaw pg 25-26)

Archaeological Survey, Ceramic Analysis, and State Formation in Western Uganda by Peter Robertshaw pg 110, The Antecedents of the Interlacustrine Kingdoms by J. E. G. Sutton pg 54)

The Ancient Earthworks of Western Uganda by Peter Robertshaw pg 17-18)

Archaeological Survey, Ceramic Analysis, and State Formation in Western Uganda by Peter Robertshaw pg 126-127)

Archaeological Survey, Ceramic Analysis, and State Formation in Western Uganda by Peter Robertshaw pg 107, Kingship and State By Christopher Wrigley pg 202, Antecedents to Modern Rwanda by Jan Vansina pg 39)

credit; Peter Robertshaw

The Antecedents of the Interlacustrine Kingdoms by J. E. G. Sutton pg 57-59

Women, Labor, and State Formation in Western Uganda by Peter Robertshaw pg 60, Archaeological Survey, Ceramic Analysis, and State Formation in Western Uganda by Peter Robertshaw pg 126, A History of Modern Uganda pg 109-110)

The salt of Bunyoro by Graham Connah pg 480

Analysis of iron working remains from Kooki and Masindi, western Uganda by Louise Iles pg 43-56

Antecedents to Modern Rwanda by Jan Vansina pg 45-46, Kingship and State By Christopher Wrigley pg 202)

The Study of the State by Henri J. Claessen pg 360-362)

Kingship and State By Christopher Wrigley pg 199-200, Antecedents to Modern Rwanda by Jan Vansina pg 219)

Kingship and State By Christopher Wrigley pg 193-196)

Beyond the Segmentary State by Peter Robertshaw pg 261-262)

Bunyoro-Kitara Revisited by GN Uzoigwe pg 21-23

The Study of the State by Henri J. Claessen pg 362-364

Fabrication of Empire: The British and the Uganda Kingdoms, 1890-1902 By D. A. Low pg 34, 37)

Khedive Ismail's Army By John P. Dunn pg 63-70

Cambridge History of Africa, Volume 5 pg 42-44

Sudan’s Wars and Peace Agreements by Stephanie Beswick pg 188-193).

Irregular Connections By Andrew P. Lyons, Harriet Lyons pg 137-138).

Explorers of the Nile by Tim Jeal pg 338-347

Explorers of the Nile by Tim Jeal pg 348

Crisis & Decline in Bunyoro by Shane Doyle pg 30, 60, Fabrication of Empire by D. A. Low pg 53)

Crisis & Decline in Bunyoro by Shane Doyle pg 31, Fabrication of Empire By D. A. Low pg 129-130

Crisis & Decline in Bunyoro by Shane Doyle pg 57-59)

The great lakes of Africa by Jean-Pierre Chrétien pg 205-207, Fabrication of Empire By D. A. Low pg 40-49

Fabrication of Empire By D. A. Low pg 76-78)

Fabrication of Empire By D. A. Low pg 79, 151-154, 186-189)

Crisis & Decline in Bunyoro by Shane Doyle pg 73-75)

for the colonial introduction of rinderpest and jiggers in east africa; Ecology Control and Economic Development in East African History by Helge Kjekshus pg 127-136

for the colonial introduction of rinderpest and jiggers in Bunyoro; Crisis & Decline in Bunyoro by Shane Doyle pg 90-91

Crisis & Decline in Bunyoro by Shane Doyle pg 73-75

Fabrication of Empire By D. A. Low pg

Crisis & Decline in Bunyoro by Shane Doyle pg 73)

service and sport on the tropical Nile by Skyes C.A pg 76

Crisis & Decline in Bunyoro by Shane Doyle pg 77

Fabrication of Empire By D. A. Low pg 209-210

"The time-honoured war with Kabarega had left Unyoro almost a barren waste, and we scarcely saw a native anywhere. With the exception of a few who lived near Masindi, those who had not been exterminated were in arms under their King. The desolation on all sides was most depressing...” This account was something else. It really underscores the apocalyptic nature of this time when a colonial soldier is getting misty eyed about the plight of the “natives.” What a read!

This was an excellent read. So heartbreaking when I think of the fact that Uganda to this day has never recovered from this brutal war of conquest.