Ancient Ife and its masterpieces of African art: transforming glass, copper and terracotta into sculptural symbols of power and ritual

Towards an understanding of naturalist (realistic) art in the African context

The art of the ancient city of Ife has since its "discovery" in the 19th century, occupied a special position in the corpus of African and global artworks; the sublime beauty, remarkable expressiveness, elegant portraiture, life-size proportions, sheer volume and sophistication of the Ife collection which included many naturalist (realistic) works was especially appealing to western observers who immediately drew parallels to some of their best art traditions particularly the ancient Greek sculptures, and ascribed mythical origins to Ife’s artists claiming their works as accomplishments beyond the capacity of an African artist, and clouding our understanding of Ife's history and its art tradition.

The sculptures of Ife are one of the legacies of the kingdom of Ife, whole capital city, ile-ife, is the center of a tradition in which its primacy and reverence is nearly unparalleled among the old world's cultures and religions: ile-ife, as the tradition goes, is the genesis of all humanity, deities and the world itself, it was the site of creation of civilization and social institutions, and its from ife that kingship, religion and the arts spread to other places. When english traders visited ile-ife, they were informed that their kings originated from ife, when missionaries went to covert the city's inhabitants, the latter said christianity was one of several religions from ife; in all contexts and in all iterations of this tradition, the city of ife was where all roads of humanity led and from where they originated1. Despite its location deep in the heart of the “forest region” of west Africa and at the periphery of the medieval world's trading theatre, Ife was the innermost west-African kingdom known to external sources of the medieval era, from the 14th century accounts of Ibn Battuta and of al-Umari (based on correspondence received from Mansa Musa), to the 15th century Portuguese accounts of an interior kingdom of great importance whose ruler was revered by many of the west-African coastal kingdoms, Ife's position in west Africa's political landscape was lofty and unequalled, much like its art.2

Beneath these grandiose traditions about Ife was a real kingdom whose wealth, based on its vibrant glass-making industry, allowed it to project its commercial power over much of the Yoruba-land (a region of south-western Nigeria with Yoruba-speakers); whose trade networks extended to the famed cities of Timbuktu and Kumbi-saleh; and whose ritual primacy as the center of the Ifa religion and philosophical school turned its’s rulers into the ultimate source of legitimation for the ruling dynasties of yorubaland, enabling Ife to establish itself as the “ritual suzerain” of the region and prompted external writers to compare the Ife ruler's position as similar to that of the Pope in medieval Europe. The distinctive sculptures of Ife, which include both naturalist and stylized works, were mostly part of ancestral shrines and mortuary assemblages, and were a product of ancestral veneration in Ife's religion, these copper-alloy and terracotta sculptures represent real personalities; both royal and non-royal, who were active in the “classical period” of Ife especially between the late 13th and early 14th century; many whom played an important role in the growth of the kingdom, as well as heads of important "houses" in the kingdom who were venerated by their descendants3. Ife's artworks were commissioned by Ife’s patrons, they were sculpted by Ife artists who employed styles and motifs common in Yoruba art using materials derived from Ife's immediate surroundings and from their inventive glass and metallurgical crafts-industries; its these artists of Ife that invented glass manufacture, making this African kingdom one of the few places in the world where glass was independently invented.

Ife's artists conveyed the visual forms and power of their patrons into sculpture in a process that was independent of the rest of the world’s art traditions which Ife's art is often compared to, the aesthetics and visual systems of Ife’s art that produced the naturalist sculptures which awed western observers (and by extension modern art observers), wasn't a natural consequence of ife's "exceptionalism" relative to the rest of the African art traditions (which would be incorrect since naturalist sculptures are present in Nubian, Asante, Benin and Kuba art among others) nor was it a “natural progression” of artistic sophistication from the abstract/stylized figures to the naturalist figures (this theory in Art history is eurocentric4 and pervades art criticism, but even in Europe its validity is debated among classical art historians who question the presumption that the naturalist Greco-roman sculpture and the medieval renaissance art it influenced, corresponded to peaks in cultural accomplishments5). Ife's naturalism, as well as its stylized art was instead a product of the political and religious concepts of expressing power and ritual that were prevalent in the kingdom at the time these sculptures were made, these highly sophisticated artworks are best interpreted within the political and religious context of the kingdom of Ife in which they were produced and not through the myopic lens of “naturalist progression” which invites superficial comparisons and misconstrues the intent behind the visual messages that Ife’s artists communicated and the rest of African artists with whom they are often unfairly juxtaposed against.

This article provides an overview of the history of the ife kingdom and the copper-alloy and terracotta sculptures made by its artists, covering the political and religious circumstances in which they were produced and the visual and ritual power they were intended to convey.

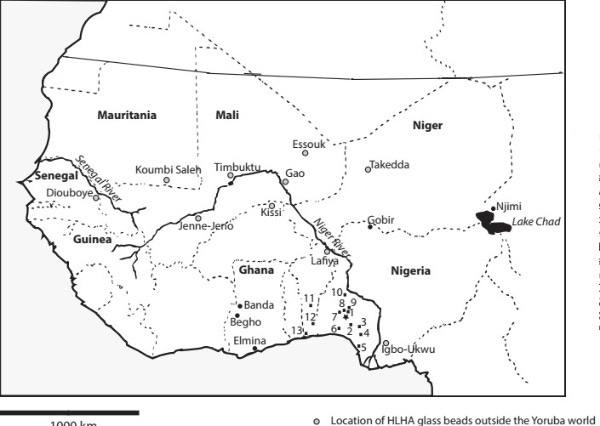

Map of the ife kingdom at its height in the 14th century and some of the cities mentioned in this article

Support AfricanHistoryExtra by becoming a member of our Patreon community, subscribe here to read more about African history, download free books, and keep this newsletter free for all:

Origins of ife and the emergence of social complexity in Yorubaland

The emergence of the ife kingdom is related in a Yoruba epic that tells a story of confrontation between two personalities of Obàtálá and Odùduwà who were a representation of several personalities and factions in classical Ife that stood for the dominant opposing camps identified with the Old order (Obàtálá) against the New order (Odùduwà). This tradition spans the period of consolidation of several small polities in the Ife heartland around the capital city ile-ife in the early 2nd millennium to the end of the classical ife in the 15th century and includes the appearance of a several real personalities such as King Obalufun II who reigned in the early 14th century. Archeological evidence indicates that the early small polities in the Yorubaland during the mid 1st millennium were an advanced form of the "house society" ; these were forms of social organizations comprised of multiple households that clustered for the purposes of reciprocity, security and self-preservation, and from which emerged rulers who managed conflicts and priestly functions, these rulers later leveraged the prosperity of their "houses" to expand their influence over other "houses" and through this process, created the earliest centralized polities. The most notable among the early yoruba states was the Oba Kingdom that arose in the last quarter of the 1st millennium. By the 9th century, the Oba kingdom had grown into a sizeable polity, wealthy enough to produce an astonishing corpus of sandstone sculptures numbering more than 800 that depicted various male and female figures as rulers, warriors, blacksmiths and musicians most of whom are shown seated, some of whom are crowned, some wear long articles of clothing and are adorned with elaborate jewellery including gemstone beads, the statues depict adult individuals rendered in stylized naturalism with figures shown in the prime of their life with unblemished bodies;6 This “Esie” soapstone art tradition of the Oba kingdom lasted well into the 14th and 15th century where it overlapped with Ife's art tradition . Another early Yoruba state was the Idoko kingdom southwest of ife which was likely inplace at the turn of the 2nd millennium and was later part of the Ijebu kingdom by the 15th century, whose capital Ijebu-Ode was enclosed within a defensive system of ramparts and walls called Sùngbo’s Erédò which enclosed an area of 1400sqkm. These early states developed a new form of political institution where a leader took on more executive roles on top of being the ceremonial role of being the mediator of conflict and the ritual head, such rulers adopted forms of regalia such as the headgear and jasper-stone beads7, and undertook public works that required a high level of organization of labor to build monuments such as the city walls and ramparts as well as palace complexes. Ife was therefore not the earliest Yoruba state but rather adopted and innovated traditions developed by its older peers to greatly enhance its political and ritual primary relative to them to create the ife-centered orientation of Yoruba world views.

Soapstone sculptures from Esie, depicting men and women with crowns and jasper beads (esie museum, nigeria)

The rampart and ditch system of ijebu-ode measures around 10 meters from the floor in its best preserved sections, the height totaling over 20 meters when the wall at its crest is included, the width of the ditches is around 5 meters and the walls were originally perfectly vertical made of hardend laterite; this “walls” system extends over 170 km and would have been one of many similar fortification systems in the yorubaland including at ile-ife and the more famous Benin “walls”

The formal period of consolidation and emergence of the centralised kingdom of Ife is dated to the 11th century when the first city wall was constructed and the earliest potsherd pavements were laid8, these constructions are the the most visible remnants of the earliest processes of political re-alignments that occurred in ife's classical era that were associated with the upheavals brought about by the confrontation between the Obàtálá and Odùduwà groups in which the former were deposed by the latter by employing the services of O̩ranmıyan, a mounted warrior associated with the Odùduwà group, after a civil war had weakened the rule of the Obàtálá9.

The deeply allegorical nature of the tradition has spawned several interpretations most of which agree with the identification of atleast three figures in the epic as real personalities: Obalufon I (a ruler from the Obàtálá group that reigned before the civil war), Obalufon II (also called Alaiyemore; he was the successor of Obalufon I and is associated with both groups), Moremi (queen consort of Obalufon II, she is also associated with both groups), and attimes the figure O̩ranmıyan who may represent ife's military expansionism or was a real figure who ruled just before Obalufon II, the latter of whom is credited as the patron of ife's arts especially the copper-alloy masks and remembered as the pacifier and peace-maker of the warring partiers along with his consort Moremi, heralding a period of peace and wealth in the kingdom10.

Other groups that feature prominently include autochthonous Igbo groups as well as the Edo of Benin kingdom; the former were a allied with the Obàtálá group and had their influence diminished by queen Moremi, this group is postulated to be related to the ancient Igbo-Ukwu bronze casters of the Nri kingdom in south-eastern Nigeria that also had a similar but older concept of divine kingship as Ife as well as an equally older naturalist bronze-casting art tradition from which Ife derived some of its motifs for displaying royal regalia.11

On the other hand, the Edo of Benin came under the orbit of Ife during the late phase of Ife's classical era and continued to regard Ife’s ruler as their spiritual senior by the time the Portuguese accounts of the kingdom were being written12, added to this melting pot of ethnicities are the Songhai-speakers (Djerma) who linked Ife to the west African emporiums of Gao and Timbuktu13the latter had since fallen under the Mali empire’s orbit during the reign of its famed emperor Mansa Musa (r. 1280 –1337AD); the presence of all these non-Yoruba speaking groups in Ife is a testament to its cosmopolitanism and augments the claim in its traditions as the origin of mankind.

Bronze roped pot, wine bowl, and vessel shaped in form of a triton snail-shell; from Igbo Ukwu, dated to the 9th century AD, (Nigeria National Museum)

Classical Ife: Art, religion, conquest and wealth

Archeologically, the tumultuous nature of the Ife epic isn't immediately apparent, ile-ife was consistently flourishing from the 12th to the early 15th century14, as indicated by the extensive potsherd pavements laid virtually everywhere within its inner walls as well as many parts of the settlements between the inner and outer walls which had a circumference of over 15km, these potsherd pavements consisted of broken pottery that was laid in neat herringbone patterns inside a fairly deep surface-section of the street that had been prepared with residual palm oil, the street was then partially backed by lighting dry wood above it, the end result was a fairly smooth smooth street whose surface integrity could last centuries without the need for extensive repair, the potsherd pavements were also used in house floors and temples floors as well as compounds surrounding them with more elaborate patterns reserved for temples and other prestigious buildings15.

The tradition of potsherd pavements seems to have been widely adopted in the westafrican cities of the early 2nd millennium in both the “sudanic” regions controlled by Mali such as the ancient city of jenne-jenno as well as the “forest regions” under Ife’s orbit although its unclear whether ife was the origin of this technology16. Added to this was the material culture of ife specifically its pottery and terracotta sculptures which span a fairly wide range of production from the 10th to 16th century.17

The peak in production of these artworks was in the 13th and 14th century when most of the copper alloy and similar terracotta sculptures were made majority of which have been found in Ife itself such as in the Wunmonije compound and the Ita Yemoo site as well as the sites of Tada and Jebba which are considerably distant from Ife18, attesting to the level of political control of Ife, whose densely settled city had an estimated population of 75-100,000 at the its peak in the 14th century19, making it one of Africa's largest cities at the time.

Potsherd pavements near Igbo-Olokun grove in ile-ife, potsherd and quartz pavements in a section of ile-ife

Ife's prosperity was derived from its monopoly on the production of glass beads that were sold across the Yoruba land and in much of “sudanic” west Africa as far as Gao, Timbuktu, Kumbi-saleh and Takedda (the old commercial capitals of the region’s empires). Ife's glass has a unique signature of high lime and high alumina content (HLHA) derived from the local materials which were used in its manufacture, a process that begun during the 11th century, the beads were made by drawing a long tube of glass and cutting it into smaller pieces, the controlled heating colored them with blue and red pigments derived from the cobalt, manganese and iron in the materials used in glas-making process such as pegmatitic rock, limestone and snail shells.20

Initially, the Yorubaland used jasper-stone beads such as those depicted on the Esie sculptures of the Oba kingdom, the jasper beads were symbols of power and worn by high ranking personalities in the region such as priests and rulers, but Ife soon challenged this by producing glass beads on industrial scale around the Olókun Grove site, the new Ife glass beads now shared the status symbolism of the jasper beads, and with the rise of centralized states in the region and the growing number of elites, their demand by elites across the region allowed Ife to create a regional order in which social hierarchy and legitimation of power was controlled and defined according to Ife's traditions. Ife’s glass beads were soon used extensively across all segments of society in the kingdom as they became central to festivities, gift giving and trade associated with various milestones in life such as marriage, conception, puberty and motherhood.

The production process of Ife’s glass was a secret that was jealously guarded by the elites of Ife (in a manner similar to the chinese’s close guarded secret of silk production), Ife’s elites invented mythical stories about its origins of the glass claiming that it came from the ground in ile-ife where it was supposedly dug, this was the story that was related to an explorer who bought a lump of raw glass from a market at a nearby city of Oyo-ile in 183021 (and was similar to the stories west African emperors such as Mansa Musa told inquisitive rulers in mamluk Egypt about Mali’s gold supposedly sprouting from the ground and being harvested like plants22) The success in guarding the manufacturing process at Ife was such that only the 268 ha. Olókun Grove site in ile-ife remained the only primary glass manufacturing site in west Africa during ife’s classical era23, with glass manufacture only reappearing at a nearby site of Osogbo in the 17th/18th centuries.

Glass studs in metal surround from Iwinrin Grove in ile-ife, glass sculpture of a snail24 (Nigeria National Museums); Glass beads from Igbo Olokun site in ile-ife25

The spread of ife-centric traditions In Yorubaland was connected to its cosmopolitanism and crafts industry that attracted communities from across the region enabling the ife elite to craft the "idea of the Yorùbá community of practice and promote itself as the head of that community" through a program of theogonical invention and revision, Ife’s elites integrated various yoruba belief systems and intellectual schools into interacting and intersecting pantheons from which the Ooni (king) of ife, derived his divine power to rule.26

Ife’s elite also elevated the ifa divination system above all others, “Ifa” refers to the system of divination in yoruba cosmology associated with the tradition of knowledge and performance of various rites and practices that are derived from 256-chapter books; each with lengthy verses, and whose vast orature and bodies of knowledge include proverbs, songs, stories, wisdom, and philosophical meditations all of which are central to Yoruba metaphysical concepts.27 These “books” constitute Ifa’s “unwritten scripture”, whose students spend decades learning and memorizing them from teachers and master diviners28.

The rulers of ife patronized the ifa school and it became the focus of rigorous learning and membership centered in the kingdom, with its most prestigious school established at Òkè-Ìtasè within ile-ife's environs; attracting students, apprentices, master diviners, and pilgrims from far in search of knowledge29 One of the most notable ifa practitioners from ile-ife was Orunmila who was born in the city ,where he became a priest of ifa, he then embarked on a journey across yorubalands, teaching students the best ifa divinations and "esoteric sciences", later returning to ile-ife where he was given an ifa scared crown and was later venerated as a deity after his passing, the career of Orunmila was was typical of men and women in a growing movement of the ifa school based in ile-Ife, dedicated to the search for and dissemination of knowledge and enlightenment30.

This movement of students and pilgrims to ifa schools in ile-ife made it the intellectual/scholarly capital of the yorubaland just like Timbuktu was the intellectual capital of “sudanic” west africa. Its within this context of Ife's intellectual prominence that Ife's form of ritualized suzerainty was imposed over the emerging polities of the yorubaland which weren't essentially united under a single government but were instead a system of hierarchically linked polities where ife was at the top, hence the creation of the Òrànmíyàn legend that is common among the Yoruba kingdoms including Oyo, Adó-Èkìtì, Àkúré, Òkò (ie:Egbá) as well as the Edo kingdom of Benin, and in all these polities, the mounted warrior prince Òrànmíyàn from Ife is claimed to have founded their dynasties through conquest and intermarriage and is often represented in the mounted-warrior sculptures found in the region’s art traditions.31

Ifa divination wooden trays from ile-ife, photos taken in 1910 (Frobenius Institute)

The wealth which the kingdom of ife generated from its glass trade enabled its rulers to import copper from the sahel region of west Africa especially from the Takedda region of Mali, as well as from the various trading routes within the region, and its within this context that Ife appears in external sources where Mansa musa mentions to al-Umari that his empire's most lucrative trade is derived from the copper they sell to Mali's southerly neighbors that they exchange for for 2/3rds its weight in gold32, one of Mali’s southern neighbors was Ife, and the kingdom was arguably the only significant independent power of the region in the 14th century following the Mali empire’s conquest of the Gao kingdom located to Ife’s northwest and the heartland of the Djerma-songhai traders active in Ife’s northern trade routes.

This northerly trade was central to ife's economy and its importance is depicted in the extension of ife's control on the strategic trading posts of Jebba and Tada which are about 200 km north of ile-ife and were acquired through military conquest during Ife’s northern campaigns which are traditionally attributed to both Òrànmíyàn and Obalùfon II. The conquest and pacification of ife's northern regions was attained by allying with the emerging Yoruba kingdom of Oyo where the Djerma traders were most active.33

Inside the Ife temples at Jebba and Tada, the Ife rulers placed sculptures associated with the Ogboni fraternity, a body of powerful political and religious leaders from Ife's old order whose position was retained throughout the classical era under the new order34, the fraternity served as a unifying regional means in the kingdom for overseeing trade, collecting debts, judging and punishing associated crime, and supervising an orderly market and road system.35

Location of ife’s glass beads in west-Africa

The more than two hundred terracotta sculptures and over two dozen copper-alloy heads in the Ife corpus are directly related to the kingdom’s religious practice of ancestral veneration which emphasized each ancestor’s individuality and a preference for idealized prime adulthood with portrait-like postures, various hairstyles, headgear, facial markings, clothing styles, religious symbols and markers of office testifying to the diversity and cosmopolitanism of ile-ife's inhabitants.

The use of sculptures to venerate ancestors was a continuation of an older practice in the Yorubaland that first occurred on a vast scale at Esie in the Oba kingdom, and it involved public and private commemoration ceremonies of the heads of "houses" of individual "house-societies" (mentioned in the introduction), the actual remains of these ancestors were interred in a central area of their respective “house compound” and the place was venerated often with a shrine built over it and attimes the remains were exhumed and reburied in different locations connected to the "house" associated with them, in a process that transformed the ancestor into a deity; but only few of the very elite families of each "house" could ascend to the status of a deity and their prominence as deities was inturn elevated by the prominence of their living descendants.

While the Esie form of ancestral veneration was less individualized and their representation on sculpture focused on communal/social identify of the personalities depicted, the Ife sculptures were individualized and emphasized each ancestor's/house's distinctiveness in such a way that it represented the very person being venerated hence the "transition" from stylized figures of Esie to the naturalism of ife. For the majority of Ife's population and royalty, these sculptures were made using fired clay (terracotta), but in the 13th and 14th centuries, the sculptures of royals were also made using copper-alloys and pure copper, and represented past kings and queen consorts as well as important figures who played a role in the truce between the Obatala and Oduduwa factions, and these 25 copper-alloy figures were commissioned in a short period by one or two rulers who included Obalufon II.36

Copper-alloy figures of a King, from the Ita Yemoo site at ile-ife, dated 1295–1435AD (National Commission for Museum and Monuments, Nigeria)37

The corpus of Ife’s art: its production, naturalist style and visual symbolism

Ife's copper-alloy sculptures were cast using a combination of the lost-wax process (especially for the life-size figures) while the rest were sculptured by hand including the majority of the terracotta figures, although both copper-alloy and terracotta sculptures exhibit the same level of sophistication particularly those commissioned for the royals which indicate a similar school of artists worked all of them, the lost-wax method used wax prints made on the face of the deceased not long after their passing, and then hand sculpting was used to even out the blemishes of old age and the already-disfigured face of the cadaver which would within a few minutes have started to show sagging skin and uneven facial muscles, this hand sculpting of the wax was done inorder to produce a plump face typical of ife’s sculptures, the waxprint was then applied to clay to sculpt the rest of the head on which uniform modeled ears were added, the eyes, lips and neck were hand-sculpted also following a uniform model and the clay fired to make the terracotta sculptures or used in the process of making the copper-alloy sculptures in a mold.38 The sculpture was later painted, its holes fixed with various adornments during the veneration ceremonies and placed in a shrine or displayed in the temple (for the case of the royal sculptures) or buried for later exhumation.39

Life-size copper-alloy heads from the Wunmonije site at ile-ife, dated 1221–136940 (Nigeria National Museum ife)

Terracotta heads from ife dated between 12th and 15th century; heads of ife dignitaries at the met museum and Minneapolis museum and the “Lajua head” of an ife court official at the Nigeria National Museum, lagos41

The naturalism of ife's heads, particularly the copper-alloys and terracotta associated with the royalty depicts real personalities in the prime of their lives; all were adults between their 30s and 40s, the heads are life size, none have blemished skin or deformities, their features are perfectly symmetrical with horizontal neck lines "beauty lines", almond-shaped eyes, full lips, well molded ears, nose and facial muscles (the last five facial features appearing to be fairly uniform across the corpus), as yoruba historian Akinwumi writes: "the sculptors generally ignored the emotional aspects and physical blemishes of these ancestors, idealizing only those features that facilitate identity and conveying a sense of perfection so that the whole composition lies between the states of “absolute abstraction and absolute likeness"42 in line with the Yoruba proverb :"It is death that turns an individual into a beautiful sculpture; a living person has blemishes"43.

The posture and expression of the portraits also conveys the power of the people they represent, as Art historian Suzane Blier writes: "the sense of calm, agelessness, beauty, and character evinced in these remarkable life-size metal heads, seems to be important in suggesting ideals of chieftaincy and governance", many of the full-body sculptures also emphasized the larger than life proportions of the head relative to the body (roughly 1:4) the primacy of the head in Ife (and Yoruba sculpture) is in line with the importance of the head in Yoruba metaphysics as well as social political factors wherein the wealth and poverty of the nation was equal to the head of its ruler, as such, Ife’s rulers and deities are portrayed in a 1:4 ratio, the diversity of ife's facial markings also represents its cosmopolitanism with the plain faced figures representing the Odùduwà linked groups while the ones with facial markings representing the Obàtálá group, and other markings represent non yoruba-speakers present at ile-ife such as the igbo and edo.44

Pure-copper mask of King Obalufon Alaiyemore at the Nigeria National Museums, Lagos; crowned heads from the Wunmonije site at the british museum and the Nigeria National museums, Lagos: all are dated to the early 14th century.45

Crowned terracotta heads from ife; head of a queen (Nigeria National museum, Lagos), crowned head of an ife royal (kimberly art museum, Crowned head of an ife royal (met museum) dated between 12th and 15th century

The corpus of ife's sculpture also includes depictions of animals linked with religious and royal power . The importance of zoomorphic metaphors in ife's political context is represented in portrayals of animals with royal regalia such as the concentric circle diadems present on the crowned heads of ife’s royal portraits and worn on the crown of present-day Ife royals, these animal sculptures were found in sites linked to themes of healing, enthronement, and royal renewal and the animals depicted include mudfish, chameleons, snakes, elephants, leopards, hippos, rams and horses.46

Included in the corpus of sculptures of exceptional beauty are works that deliberately depict deformities, unusual physical conditions and disease that are signifiers of deity anger at the breaking of taboos47, equally present are motifs such as one that depicts birds with snake wings and a head with snakes emerging from the nostrils; both of which were powerful visual symbols for death and transformation and are associated with the O̩batala pantheon; these motifs are found on the medallions of many ife and Yoruba artworks as well as in Benin's artworks.48 other sculptures include staffs of office, decorated pottery and thrones, the last of which includes a life-size throne group depicting a ruler seated on a large throne whose top was partially broken.49

Terracotta heads of animals from ife of a hippo, elephant and a ram, decorated with regalia, found at the Lafogido site in ile-ife, dated to the early 14th century (Nigeria National Museums, Lagos)50

Copper-alloy cast of a ruler wearing an embroidered robe and medallions with snake-winged bird and head with snake-nostrils, from Tada, dated to 1310–1420; Copper-alloy cast of a archer figure wearing a leather tunic and a medallion with a snake-winged bird, from Jebba, dated to the early 14th century; copper cast of a seated figure making an Ogboni gesture, dated to the early 14th century (Nigeria National Museums, Lagos)51

Life-size broken terracotta sculpture of an Ife ruler on a throne with his foot resting on a four-legged footstool, top right is one of the broken pieces from this sculpture, its of a life-size hand holding a child’s foot; both were found in the Iwinrin Grove site. at ile-Ife, bottom right is a miniature sculpture of an ife throne made from pure quartz (the throne group is in the Nigeria national museum, ife, while the side sculptures are at the British museum BM Af1959,20.1 and Af1896,1122.1)

Ife’s collapse and legacy

Ife's art tradition ended almost abruptly in the 15th century, tradition associates the end of Obalufun II's reign with various troubles including an epidemic of small pox which had been recurring in ife's history but was particularly devastating at the close of his reign in the late 14th century which, coupled with a drought, led to the decline of urban population in Ife in the early 15th century, the economic and demographic devastation wrought by this combined calamity was felt across all sections of the kingdom including the elite and greatly affected the veneration rituals as well as the sculptural arts associated with them as the surviving great sculptors of Ife lost their patronage and ife's population was dispersed.52

A similar tradition also holds that a successor of Obalufon II named King Aworolokın ordered the killing of the entire lineage of Ife artists after one of them had deceived the monarch by wearing the realistic face mask of his predecessor (most likely the copper mask shown above)53 Archeologically, this end of Ife is indicated by the end of the potsherd pavement laying, abandonment of many sections within the city walls and the recent evidence for the bubonic plague (black death) that reached the region in the 14th century may have recurrently infected large sections of the population in later centuries.54

The legacy of Ife's artworks, intellectual traditions and glorious past was carried on by many of the surrounding kingdoms in south-western Nigeria most notably the Yoruba kingdom of Oyo to its north and the Edo kingdom of Benin to its south which draws much of its artistic influences from ife and its from Benin that we encounter the least ambiguous reference to Ife among the earliest external accounts on the kingdom: writing in the 1550s, the Portuguese historian João de Barros reproduced an account related to him by a Benin kingdom ambassador to Portugal that was in Lisbon around 1540 : "Two hundred and fifty leagues from Beny, there lived the most powerful monarch of these parts, who was called Ogané. . . . He was held in as great veneration as is the Supreme Pontif with us. In accordance with a very ancient custom, the king of Beny, on ascending the throne, sends ambassadors to him with rich gifts to announce that by the decease of his predecessor he has succeeded to the kingdom of Beny, and to request confrmation. To signify his assent, the prince Ogané sends the king a staff and a headpiece of shining brass, fashioned like a Spanish helmet, in place of a crown and sceptre. He also sends a cross, likewise of brass, to be worn round the neck, a holy and religious emblem similar to that worn by the Knights of the Order of Saint John. Without these emblems the people do not recognize him as lawful ruler, nor can he call himself truly king"55.

ile-ife was re-occupied in the late 16th century and partially recovered in the 17th and 18th century but the city only retained its religious significance but lost its political prestige as well as its surrounding territories56 to the Oyo kingdom and its commercial power to the Benin kingdom, in the 19th century, the region was engulfed in civil wars following the collapse of the Oyo empire and order was only reestablished in the last decades of the century just prior to the region's colonization by the British. Nevertheless, the ritual primacy of ife continued and its lofty position in the Yoruba world system was retained even in the colonial era and to this day it remains the ancestral birthplace of the Yoruba, and the for millions of them; it is the sacred center of humanity’s creation.

Conclusion: Ife and African art

The picture that emerges from ife's art tradition in the context of its religious and political history dispels the misconceptions about its production as well as its significance; Ife's naturalism was a product of its individualized form of ancestor veneration that emerged during the classical era and was opposed to the more communal form of veneration in the older Esie art tradition as well as the later traditions in Yoruba land after the 15th century, the proportions of Ife’s sculptural figures was intended solely to convey ideals of ritual and power of the personality depicted, and the peak of production in the early 14th century was due to the actions of few patrons in the short period of Ife's height hence the fairly similar level of sophistication of the sculptures associated with royal figures/deities.

Ife’s art tradition and its fairly short fluorescence period was unlike Benin’s whose commemorative heads were produced over a virtually unbroken period from the 16th to the 19th century, but it was instead similar to the Benin brass plaques that were mostly carved almost entirely in the 16th century. The above overview of Ife's art reveals the flaw in interpretations of naturalism in African (and world art in general), the artists sculpting these works were communicating visual symbols that could be understood by observers familiar with them, this is contrary to the modern eurocentric ideals of what constitutes sophisticated art which, through the lens of universalism, sees art as a progression from abstract forms (which they term “primitive”) to naturalist forms (which they term “sophisticated”), but the vast majority of artists weren't primarily making artworks to reproduce nature but were conveying symbols of power, ritual, as well as their society’s form of aesthetics through visual mediums such as sculpture and painting, in a way that was relevant to the communities in which they were produced.

The sophistication of Ife’s art is derived from the visual power of the figures they represent, men and women who once walked the sacred ground of ile-ife, and ascended to become gods, to be forever venerated by their descendants.

for free downloads of books on the Yoruba civilization and art, and more on African history , please subscribe to my Patreon account

A history of the yoruba people by Stephen Adebanji Akintoye pg 18-19

Art and Risk in Ancient Yoruba by Suzanne Blier pg 6)

The Yoruba: a new history by Akinwumi Ogundiran pg 75-81

Thinking with Things: Toward a New Vision of Art by Esther Pasztory pg 192

The Invention of Art History in Ancient Greece by Jeremy Tanner pg 67-70, Rethinking Revolutions Through Ancient Greece by Simon Goldhill pg 68-71

The Yoruba: a new history by Akinwumi Ogundiran pg 57-59)

The Yoruba: a new history by Akinwumi Ogundiran pg 60)

The Yoruba: a new history by Akinwumi Ogundiran pg 65)

Art and Risk in Ancient Yoruba by Suzanne Blier pg 37-39)

Art and Risk in Ancient Yoruba by Suzanne Blier pg 39,41)

Art and Risk in Ancient Yoruba by Suzanne Blier pg 40, 223

Art and Risk in Ancient Yoruba by Suzanne Blier 40,87, The Yoruba: a new history by Akinwumi Ogundiran pg 160

The Yoruba: a new history by Akinwumi Ogundiran pg 27)

A dictionary of archaeology by ian shaw pg 296

Material Explorations in African Archaeology by Timothy Insoll pg 246

Mobilité et archéologie le long de l’arc oriental du Niger by Anne Haour

Heroic Africans: Legendary Leaders, Iconic Sculptures by Alisa LaGamma pg 62)

Art and Risk in Ancient Yoruba by Suzanne Blier pg 252-254, 42-58)

The Yoruba: a new history by pg 68)

Chemical analysis of glass beads from Igbo Olokun by by AB Babalola

The Yoruba: a new history by Akinwumi Ogundiran pg 93

African Dominion by Michael Gomez pg 121

The Yoruba: a new history by Akinwumi Ogundiran pg 97-105)

Art and Risk in Ancient Yoruba by Suzanne Blier pg 494,299

Chemical analysis of glass beads from Igbo Olokun by by AB Babalola

The Yoruba: a new history by Akinwumi Ogundiran pg 128-129, 135

Deep knowledge : Ways of Knowing in Sufism and Ifa by Oludamini Ogunnaike pg 196

The Yoruba: a new history by Akinwumi Ogundiran pg 130-131

The Yoruba: a new history by Akinwumi pg 134-135)

A history of the yoruba people by Stephen Adebanji Akintoye pg 83-84)

The Yoruba: a new history by Akinwumi Ogundiran pg 110-111)

The Yoruba: a new history by Akinwumi pg 145)

The Yoruba: a new history by Akinwumi pg 124-125)

A history of the yoruba people by Stephen Adebanji Akintoye pg 75)

Art and Risk in Ancient Yoruba by Suzanne Blier pg 58)

The Yoruba: a new history by Akinwumi Ogundiran pg 75-79)

Art and Risk in Ancient Yoruba by Suzanne Blier pg 204-205

Art and Risk in Ancient Yoruba by Suzanne Blier pg 283-287)

Art and Risk in Ancient Yoruba by Suzanne Blier pg 83, 249, 260-1

Art and Risk in Ancient Yoruba by Suzanne Blier pg 251-259

Art and Risk in Ancient Yoruba by Suzanne Blier 69,83

The Yoruba: a new history by Akinwumi Ogundiran pg 76)

Art and Risk in Ancient Yoruba by Suzanne Blier pg 159

Art and Risk in Ancient Yoruba by Suzanne Blier pg 159-160, 271-275, 254, 162-166, 203-241)

Art and Risk in Ancient Yoruba by Suzanne Blier pg pg 14, 234, 68,

Art and Risk in Ancient Yoruba by Suzanne Blier pg 288-335)

Art and Risk in Ancient Yoruba by Suzanne Blier pg 124, 184-187

Art and Risk in Ancient Yoruba by Suzanne Blier pg 193-188,

Art and Risk in Ancient Yoruba by Suzanne Blier pg 427-438)

Art and Risk in Ancient Yoruba by Suzanne Blier pg 297

Art and Risk in Ancient Yoruba by Suzanne Blier pg 57,58,15 )

The Yoruba: a new history by Akinwumi Ogundiran pg 154-159)

Art and Risk in Ancient Yoruba by Suzanne Blier pg 65)

Reflections on plague in African history (14th–19th c.) Gérard L. Chouin

The Yoruba: a new history by Akinwumi Ogundiran pg 94)

The Yoruba: a new history by Akinwumi Ogundiran pg 201-2)

"

Other groups that feature prominently include autochthonous Igbo groups as well as the Edo of Benin kingdom; the former were a allied with the Obàtálá group and had their influence diminished by queen Moremi, this group is postulated to be related to the ancient Igbo-Ukwu bronze casters of the Nri kingdom in south-eastern Nigeria that also had a similar but older concept of divine kingship as Ife as well as an equally older naturalist bronze-casting art tradition from which Ife derived some of its motifs for displaying royal regalia.

"

I don't think the "Igbo" people here are in any way related to the current day Igbo people. Your source is not a Nigerian and it's very very easy for outsiders to mix them up.