Anti-slavery laws and Abolitionist thought in pre-colonial Africa

the view from Benin, Kongo, Songhai and Ethiopia.

In 1516, the King of Benin imposed a ban on the exportation of slaves from his kingdom. While little is known about the original purpose of this embargo, its continued enforcement for over two centuries during the height of the Atlantic slave trade reveals the extent of anti-slavery laws in Africa.1

A lot has been written about the European abolitionist movement in the 19th century, but there's relatively less literature outlining the gradual process in which anti-slavery laws evolved in response to new forms of slavery between the Middle Ages and the early modern period.

For example, while many European states had anti-slavery laws during the Middle Ages2, the use and trade in slaves (mostly non-Christian slaves but also Orthodox Christian slaves3) continued to flourish, and the later influx of enslaved Africans in Europe after the 1500s4 reveals that the protections provided under such laws didn't extend to all groups of people.

The first modern philosopher to argue for the complete abolition of slavery in Europe was Wilheim Amo —born in the Gold Coast (Ghana)— who in 1729 defended his law thesis ‘On the Rights of Moors in Europe’ using pre-existing Roman anti-slavery laws to argue that protections against enslavement also extended to Africans5. Amo's thesis, which can be considered the first of its kind in modern abolitionist thought, would be followed up by better-known abolitionist writers such as Ignatius Sancho, Olaudah Equiano, and William Wilberforce.6

Portrait of Sancho, ca. 1768. The fact that the first and most prominent abolitionist thinkers in Europe were Africans should not be surprising given that it was they who were excluded from the anti-slavery laws of the time.

However, such abolitionist thought would largely remain on paper unless enforced by the state. Official abolition of all forms of slavery that was begun by Haiti in 1807, followed by Britain in 1833 and other states decades later, often didn't mark the end of the institution's existence. Despite abolition serving as a powerful pretext to justify the colonial invasion of Africa, slavery continued in many colonies well into the 20th century.7

Abolition should therefore be seen as a gradual process in which anti-slavery laws that were initially confined to the subjects/citizens of a society/state were extended to everyone. Additionally, the efficacy of the anti-slavery laws was dependent on the capacity of the state to enforce them. And just as anti-slavery laws in European states were mostly concerned with their citizens, the anti-slavery laws in African states were made to protect their citizens.

In the well-documented case of the kingdom of Kongo, the enslavement of Kongo's citizens was strictly forbidden and the kings of Kongo went to great lengths to enforce the law even during periods of conflict. During the 1580s and the 1620s, thousands of illegally enslaved Kongo citizens were carefully tracked down and repatriated from Brazil in response to demands by the Kongo King Alvaro I (r. 1568-1587) and King Pedro II (r. 1622-1624). Kongo's anti-slavery laws were well-known by most citizens, in one case, a Kongo envoy who had stopped by Brazil on his way to Rome managed to free a person from Kongo who had been illegally enslaved.8

Anti-slavery laws at times extended beyond states to include co-religionists. In Europe, anti-slavery laws protected Christians from enslavement by co-religionists and export to non-Christians, despite such laws not always being followed in practice.9 Similarly in Africa, Muslim states often instituted anti-slavery laws against the enslavement of Muslims. 10 (again, despite such laws not always being followed in practice.)

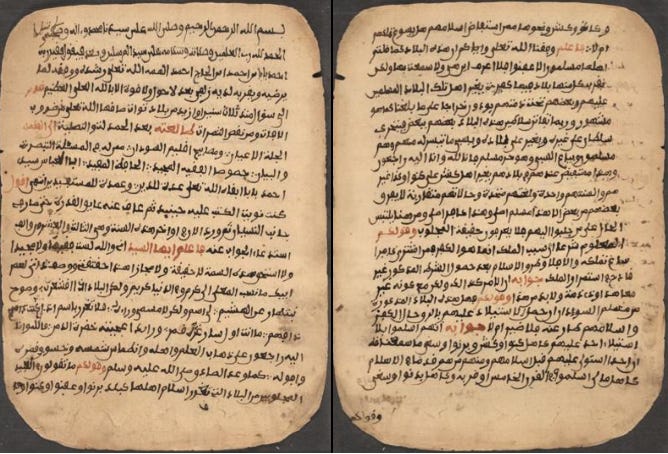

The protection of African Muslims against enslavement was best articulated in the 17th-century treatise of the Timbuktu scholar Ahmad Baba titled Miraj al-Suud ila nayl Majlub al-Sudan (The Ladder of Ascent in Obtaining the Procurements of the Sudan). Court records from Ottoman Egypt during the 19th century include accounts of several illegally enslaved African Muslims who successfully sued for their freedom, often with the help of other African Muslims who were visiting Cairo.11

Copy of Ahmad Baba’s treatise on slavery, Library of Congress12

African Muslim sovereigns such as the kings of Bornu not only went to great lengths to ensure that their citizens were not illegally enslaved, but also demanded that their neighbors repatriate any enslaved citizens of Bornu13. Additionally, the political revolutions that swept 19th-century West Africa justified their overthrow of the pre-existing authorities based on the pretext that the latter sold freeborn Muslims to (European) Christians. After the ‘revolutionaries’ seized power, there was a marked decrease in slave exports from the regions they controlled.14

The evolution of anti-slavery laws and abolitionist thought in Africa was therefore determined by the state and the religion, just like in pre-19th century Europe before such protections were later extended to all.

In Ethiopia, anti-slavery laws and abolitionist thought followed a similar trajectory, especially during the 16th and 17th centuries. Pre-existing laws banning the enslavement and trade of Ethiopian citizens were expanded, and philosophers called for the recognition of all people as equal regardless of their origin.

The anti-slavery laws and abolitionist philosophy of Ethiopia during the 16th and 17th centuries are the subject of my latest Patreon article;

Please subscribe to read more about it here:

Benin and the Europeans, 1485-1897 by A. F. C. Ryde pg 45, 65, 67, The Slave Trade, Depopulation and Human Sacrifice in Benin History by James D. Graham, A Critique Of The Contributions Of Old Benin Empire To The Trans-Atlantic Slave Trade by Ebiuwa Aisien pg 10-12

The Cambridge World History of Slavery: Volume 2 pg 30-35)

That Most Precious Merchandise: The Mediterranean Trade in Black Sea Slaves, 1260-1500 by Hannah Barker pg 12-38, The Cambridge World History of Slavery: Volume 2 pg 433-438, 466-470, 482-506)

A Social History of Black Slaves and Freedmen in Portugal, 1441-1555 By A. Saunders pg 35-45

Belonging in Europe - The African Diaspora and Work edited by Caroline Bressey, Hakim Adi pg 40-41, Anton Wilhelm Amo's Philosophical Dissertations on Mind and Body pg 10-12

The Slave's Cause: A History of Abolition By Manisha Sinha pg 25-26, 123-126, Slavery and Race: Philosophical Debates in the Eighteenth Century By Julia Jorati 187-192, 267.

The End of Slavery in Africa By Suzanne Miers 7-25

Abolitionism and Imperialism in Britain, Africa, and the Atlantic edited by Derek R. Peterson pg 38-53, Slavery and its transformation in the kingdom of kongo by L.M.Heywood, pg 7, A reinterpretation of the kongo-potuguese war of 1622 according to new documentary evidence by J.K.Thornton, pg 241-243

That Most Precious Merchandise: The Mediterranean Trade in Black Sea Slaves, 1260-1500 by Hannah Barker pg 39-55

Slaves and Slavery in Africa Volume 1 edited by John Ralph Willis pg 3-7)

Slaves and Slavery in Africa Volume 1 edited by John Ralph Willis pg 125-137, Slaves and Slavery in Africa: Volume Two: The Servile Estate By John Ralph Willis pg 146-149)

The Cambridge World History of Slavery: Volume 3 pg 66-67)

Jihād in West Africa During the Age of Revolutions by Paul E. Lovejoy

The Kurukan Fuga undertaken by Sundiata Keita deserved a shout out, keep up the good work love what you are doing.

The destruction and rejection of the previously accepted sovereignty of Africa’s kingdoms was a sad turning point.