Christian Nubia, Muslim Egypt and the Crusaders: a complex mosaic of Diplomacy and Warfare.

The kingdom of Makuria, a medieval African power.

For more than six centuries, the Nubian kingdom of Makuria is said to have maintained a relatively cordial relationship and the various Muslim dynasties of Egypt which was quite unique for the era; merchants from both countries plied their trades in either cities, pilgrims travelled safely through both regions, and ideas flowed freely between the two cultures, influencing the artistic, literary and architectural traditions of both states. Scholars have for long attributed this apparent peaceful co-existence to the baqt treaty, according to a 15th century writer, the baqt was a written agreement between the Makurians and the Rashidun caliphate (the first Muslim state to conquer Egypt) in which the two sides agreed to terms of settlement that favored the Muslim Egyptians, with Makuria supposedly having to pay jizyah (a tax on Christian subjects in Muslim states), maintain the mosque at Old Dongola and deliver a fixed quota of slaves. Historians have for long taken this account as authoritative despite its late composition, they therefore postulated that to the Muslim dynasties of Egypt, the kingdom of Makuria was a client state; a Christian state whose special status was conferred onto it by its more powerful neighbor, and that the peaceful relationship was dictated by the Muslim dynasties of Egypt.

Recent re-examinations of the texts relating to this baqt peace treaty as well as the relationship between Makuria and the Muslim dynasties of Egypt however, reveal a radically different picture; one in which the Makurian armies twice defeated the invading Rashidun armies in the 7th century and in the succeeding centuries repeatedly advanced into Muslim Egypt and played a role in its internal politics, supporting the Alexandrian Coptic church and aiding several rebellions. Rather than the long peace between Makuria and Egypt postulated in popular historiography, the relationship between the two states alternated between periods of active warfare and peace, and rather than Muslim Egypt dictating the terms of the relationship; Makuria imposed the truce on the defeated Egyptian armies and carried out its relationship with Egypt on its own terms often maintaining the balance of power in its favor and initiating its foreign policy with Egypt; the latter only having to react to the new state of affairs. This relationship significantly changed however once the crusaders altered the political landscape of the Near east, their conquest of the Christian ‘holy lands’ and establishment of crusader states created a radically different dynamic; the threat of Makuria allying with the crusader states and combined with both Christian states' attacks into Muslim Egypt in the 12th century led to the emergence of a military class in Egypt which seized power and attacked the Christian states on both fronts; advancing south into Makuria and north into the crusader states in the late 13th century, managing to conquer the latter but failing to pacify the former for nearly two centuries until Makuria's eventual demise from internal processes.

This article explorers the relationship between Makuria and the Muslim dynasties of Egypt, focusing on the prominent events that shaped their encounters, the relationship between the crusaders and Christian Nubia and the gradual decline of Makuria

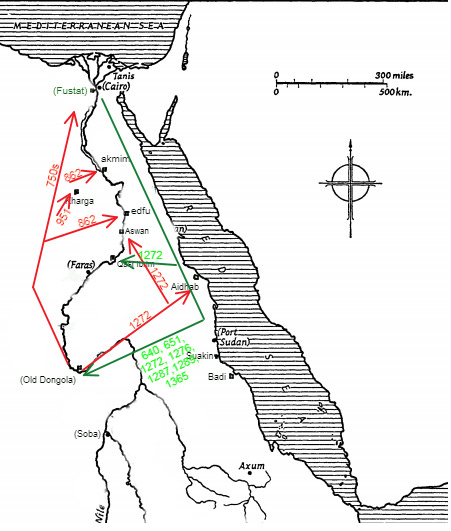

Map of medieval North-east Africa, showing the wars between Makuria and Muslim Egypt

Support AfricanHistoryExtra by becoming a member of our Patreon community, subscribe here to read more about African history, download free books, and keep this newsletter free for all:

First encounters: the emergence of Makuria, warfare, Egypt’s defeat, and an uneasy peace.

The fall of the kingdom of Kush in the late 4th century was followed by the emergence of several Nubian small states along the length of its territories; with Noubadia emerging in the 5th century in the northern most regions (southern Egypt), Makuria and Alodia by the 6th century (in what is now north and central Sudan). In all three new kingdoms new capitals were established and they became centers of political and religious power; the heavily fortified city of city of Old Dongola (or Tungul) emerged as the center of the centralized state of Makuria by the 6th century with Faras as the capital of Noubadia and Soba as the capital of Alodia, after a number of Byzantine missions in the mid 6th century, the royal courts of the three kingdoms adopted Christianity, which became the state religion.1

The ruins of the 7th century Kom H monastery at Old Dongola

The ruins of Sabagura, a 6th century Noubadian city

Makuria defeats the Rashidun caliphate and imposes a the baqt treaty

Between 639 and 641, the Arab armies of the Rashidun caliphate had conquered much of Egypt from byzantine control and soon after, advanced south to conquer the territory of the Nubians. In 641, the Rashidun force under the leadership of famous conquer Uqba Ibn Nafi penetrated south of Aswan and further into the territory of the kingdom of Noubadia (which at the time was independent of Makuria, its southern neighbor); it was against the Noubadian military that Uqba's first invasion was fought in 641/6422, the chronicler Al-Baladhuri (d. 892) describes the battle which was ultimately won by the Noubadian armies as such : "When the Muslims conquered Egypt, Amr ibn al-As sent to the villages which surround it cavalry to overcome them and sent 'Uqba ibn Nafi', who was a brother of al-As. The cavalry entered the land of Nubi like the summer campaigns against the Greeks. The Muslims found that the Nubians fought strongly, and they met showers of arrows until the majority were wounded and returned with many wounded and blinded eyes. So the Nubians were called 'pupil smiters … I saw one of them [i.e. the Nubians] saying to a Muslim, 'Where would you like me to place my arrow in you', and when the Muslim replied, 'In such a place', he would not miss. . . . One day they came out against us and formed a line; we wanted to use swords, but we were not able to, and they shot at us and put out eyes to the number of one hundred and fifty."3.

Undeterred by this initial defeat however, the Rashidun armies would again send an even large force to conquer Nubia in 651 under the command of Abd Allah who now faced off with the combined Noubadian and Makurian army led by King Qalidurut of Makuria, this attack took place in the same year the Aksumite armies were attacking Arabia and the speed with which Abdallah's forces moved south, bypassing several fortified cities in the region of Noubadia was likely informed by the urgency to counter the threat of what he thought was as an African Christian alliance between Aksum and Makuria4

Abdallah's forces besieged Old Dongola and shelled its fortifications and buildings using catapults that broke down the roof of the church, this engagement was then followed by an open battle between the Makurian forces and the Rashidun armies in which the latter suffered many causalities ending in yet another decisive Nubian victory, as the 9th century historian Ahmad al-Kufı wrote: "When the Nubians realized the destruction made in their own country, they . . moved to attack the Moslems so bravely that the Moslems had never suffered a loss like the one that they had in Nubia. So many heads were cut off in one battle, so many hands were chopped, so many eyes smitten by arrows and bodies lying on the ground that no one could count".5

In light of this context of defeat it was therefore the Rashiduns who sued for peace rather than the Makurians, as the historian Jay Spaulding writes "it is unlikely that the party vanquished at Old Dongola would have been in a position to impose upon the victors a treaty demanding tribute and unilateral concession" The oldest account of this "truce of security" treaty was written by the 9th century historian Ibn Abdal-Hakam, it was understood as an unwritten obligation by both parties to maintain peaceful relations as well as a reciprocal exchange of commodities annually known as the baqt wherein the Muslims were to give the Makurians a specified quantity of wheat and lentils every year while the Makurians were to hand over a certain number of captives each year.6

Centuries later however, the succeeding Muslim dynasties of egypt conceived the original treaty as a written document obliging the Nubians to pay tribute in return for the subordination to the caliphate, but the actions of the kings of Makuria reveals that the original treaty's intent continued to guide their own policy towards Muslim Egypt.7

The makurian fortresses of Hisn al-Bab and el-usheir occupied from the 6th to 15th century

Makuria and the first Muslim dynasties of Egypt; the Ummayads (661-750), the Abbasids (750-969)

The unification of Noubadia with Makuria took place during the reign of king Qalidurut in the face of the Rashidun invasion of both kingdoms and siege of Old Dongola that year, but this unification wasn't permanent and the two kingdoms split shortly after, only to be reunified during the reign of Merkurios8 (696-710) who also introduced the policy of religious tolerance; uniting the Chalcedonian and Miaphysite churches of either kingdoms, the latter of which was headed by the coptic Pope of Alexandria who from then on appointed the archbishops at Old Dongola.9

While the now much larger kingdom Makuria flourished, an uneasy peace with Muslim Egypt followed and during the reign of Ummayad caliph Hišām (r. 724-743), the Ummayad armies twice invaded Makuria but were defeated, and in retaliation to this; the Makurian army under King Kyriakos invaded Egypt twice, reportedly advancing as far as its capital Fustat,10 ostensibly to force the Ummayad governor of Egypt to restore the persecuted Alexandrian pope Michael (r. 743–67) after the Makurians had learned of the ill-treatment he had suffered, as well as his imprisonment and the confiscation of his finances, the Makurian army is said to have done considerable damage to the lands of Upper Egypt during this attack until the governor of Egypt released the patriarch from prison, Kyriakos's army then returned to Makuria and peace between the Ummayads and Makurians resumes.11

Similar attacks from the Makurian army on the then Abbasid controlled Egypt are recorded in 862 at Akhmin that also included the cities of Edfu and Kom Ombo, a significant portion of upper Egypt (the region geographically known as southern Egypt) was occupied by the Makurians in the 9th century and Edfu became a center of Nubian culture until the 11th century.12 At a time when the Muslim population of Egypt is said to have surpassed the Christian population.

During this time, Abbasid governor of Egypt Musa Ibn Ka'ab (r. 758–759) complained about the decorating state of relations between Makuria and Abbasid Egypt, writing to the Makurian king Kyriakos that "Here, no obstacle is placed between your merchants and what they want, they are safe and contented wherever they go in our land. You, however behave otherwise, nor are our merchants safe with you"13 and he demanded that the Makurian king pays 1,000 dinars for an Egyptian merchant who had died in Makuria14, but there's reason to doubt this claim by the governor about the safety of Nubian traders in egypt as another contemporary account writes that the "Arabs ‘were in the habit of stealing Nubians and sold them as slaves in Egypt [al-Fusṭāṭ]".15

In 830, an embassy from the Abbasid caliph at Baghdad arrived at the court of the Makurian King Zacharias demanding payment of about fourteen years of arrears in Baqt payments, King Zacharias is however only ruling as a regent of the rightful king George whom he sends to Bagdad to negotiate the terms of the treaty16, which at this time had been re-imagined by the Abbasid judges as a customary payment of 360-400 slaves a year from Makuria in exchange for Egyptian wheat and textiles, but the boy-king George explained that Makuria had no capacity to acquire that number of slaves, (indeed, the only instance of Makuria sending slaves to Egypt in the context of baqt before the 13th century was when it exported two slaves), the Abbasid caliph then agreed to lower the obligation by 2/3rds of the previous figure and king George returned to Makuria, but there is little evidence that this lower figure of slaves was remitted by king George nor by his successors until the late 13th century.17 Besides, the attacks that the Makurians launched into Abbasid Egypt in 862, a few decades after these negotiations, and the Makurian occupation of much of upper Egypt upto Edfu for nearly three centuries reveals the relative weakness of Abbasid control in their southern region, much less the ability to ensure the Makurians met their obligations.

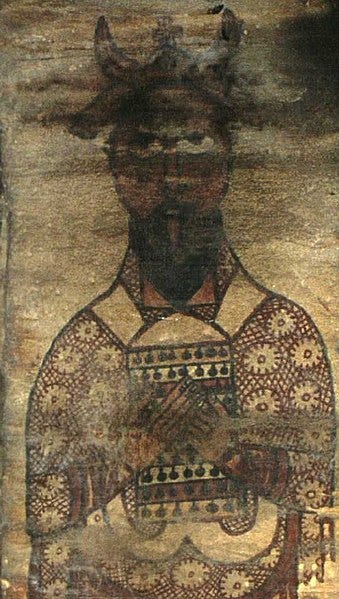

Painting of the members of the royal court of Makuria from Old Dongola, commissioned by King Ioannes II (c. 770–804 AD)

Makuria and late-period Abbasid Egypt; its offshoot dynasties and the rise of the slave armies.

During the late Abbasid period in the 9th century; its offshoot dynasties of the Tulunids (868–905) and the Ikshdids (935-969); as well as the era of the Fatimid caliphate (969-1171), the institution of slave armies in Muslim Egypt was greatly expanded, these slaves taken from a diverse range of ethnicities and were reputed to be fiercely loyal to their Kings which allowed the latter to centralize their power, the bulk of military slaves were Turks, Greeks, and Armenians but a sizeable percentage were African; especially during the period between the 9th and 12th century.18

While the African portion of these armies is often thought to have been purchased from Nubia19, there are several reasons why Makuria is very unlikely to have been the source, one is that the use of African slave soldiers which increased during the Tulunid and Fatimid era, and later sharply declined in the Ayyubid and Mamluk era in the 12th and 13th century,20 contrasts with the period when slaves from Makuria are documented to have been exported into Egypt in the 13th/14th century; these slaves are often associated with the Mamluk wars with Makuria and the latter’s payment of the baqt, added to this reason is the above mentioned lack of significant Nubian slave trade prior to the Mamluk invasion as well as the lack of mention of slave trade from 10th century descriptions on Makuria made by travelers, all of which make it unlikely that the more 30-40,000 African soldiers of Muslim Egypt passed through Makurian cities unnoticed. The most likely source for these were the red-sea ports of Aidhab and Badi (where a significant slave market existed in the 8th century), and from the Fezzan region of southern Libya; where a large slave market existed in the city of Zawila from the 8th to the 12th century, many of whom were ultimately sold to the Maghreb and Muslim Egypt21.

Despite the red sea region primarily falling under the political orbit of the Muslim empires that also controlled Egypt, the ports of Aidhab and Badi were also politically important for the kingdom of Makuria, Aidhab was founded during the reign of Rashidun caliph Abû Bakr [632-34] while Bâdi was founded in 637, the latter was established to contest Aksumite hegemony over the red sea which it had maintained through its port of Adulis in Eritrea, while the former served as a base for the conquest of Egypt22, both ports traded in the usual African commodities of gold, cattle, ivory and slaves, but it was slaves that became important to its trade in the 8th century. These slaves were drawn from various sources but primarily from the neighboring Beja groups. In the late 9th century, Gold became the primary export of Aidhab, most of it was mined from Wadi Allaqi in the eastern desert 23 and brought through caravan routes to the coast, along these routes; goods, pilgrims and caravans travelled from Aidhab to Aswan from where they were sold to Fustat.

medieval ruins of Deraheib in the Wadi Allaqi region a region in the eastern desert under Beja control24

In 951 and 956, more invasions from the Makurian army into upper Egypt are recorded that reached upto the western oases of the desert at Kharga and the city of Aswan, these inturn led to an invasion into the northern parts of Nubia by the forces of the Ikhshidid egypt which briefly captured Qsar Ibirim in 957, the later action promoted a response from the Makurian army that advanced as far north as Akhmin in 960s and occupied much of the region for atleast 3 years25. in 963, the Ikhshidid army led by the famous African slave general Kafur al-Ikhshidi attacked Makuria reportedly upto Old dongola26 although there’s reason to doubt this claim27, this invasion was soon retaliated by another Makurian attack shortly before his death in 968. After the Fatimid conquest of egypt in 969, relations between the Fatimid sultans and the kings of Makuria became much better save for a minor raid by the rebellious Turkish slave Nasir ad-Dawla who led his forces into Makuria in 1066 but was crushingly defeated by the Makurian army28, No wars were conducted by any of the Fatimid caliphs into Makuria and none were conducted by the Makurian kings into Egypt for the entire period of Fatimid rule.

The lull in warfare between Makuria and Egypt from the 10th to the late 12th century allowed for an extensive period of trade and cultural exchanges between the two states, coinciding with the unification of Makuria and the southern Kingdom of Alodia to form the Kingdom of Dotawo in the mid 10th century29

The long peace between Makuria Fatimid Egypt: Trade, pilgrimage, correspondence and the coming of the crusaders

Evidence for this relatively peaceful coexistence is provided by the appearance of several Makurian Kings in Fatimid Egypt beginning with King Solomon who left Nubia for Egypt after his abdication, where he retired to the church of Saint Onnophrios near Aswan and died later in the 1070s30 to be buried in the monastery of St George at Khandaq.31 This act of personal piety by King Solomon who believed that “a king cannot be saved by God while he still governs among men”32 would be repeated by successive Makurian Kings from the 11th through the 13th centuries, including King George who ascended to the throne in 1132, and left for Egypt after his abdication to retire to an Egyptian monastery in Wadi en-Natrun where he later died in the late 1150s33.

Nubian pilgrims as well found it much easier to journey through Egypt on their way to the holy lands as well as to other Christian states in Europe such as the Byzantine empire; the Makurian King Moses George (who reigns during the end of the Fatimid era) also abdicated the throne to travel to Jerusalem, he later reached Constantinople in 1203 where he was met by the crusader Robert de Clari, whose chronicle of the Fourth Crusade mentions a black Christian king with a cross on his forehead who had been on a pilgrimage through Jerusalem with twelve companions, although only two continued with him to Constantinople34, the King said he was on his way to Rome and ultimately to the church of Santiago de Compostela in Spain.35

Moses George’s pilgrimage to Jerusalem and parts of the Byzantine realm was part of a larger stream of Christian pilgrims from Nubia into the holy lands, several of whom were mentioned by Theoderich in 117236 and by Burchard of Mount Sion in 1280AD when they had obtained possession of Adam’s Chapel in the Church of the Holy Sepulcher37 . Direct contacts between Makuria and Christian Europe which now included European travelers and traders visiting Old Dongola, thus provided European cartographers, diplomats, church officials, and apocalyptic mythographers with more material for locating Nubia within the wider sphere of Christendom38. The Makurian economy was relatively monetized using Fatimid coinage which arrived through external trade, these coins were used in purchasing land and other commodities by the Makurians as well as in paying rent and taxes39

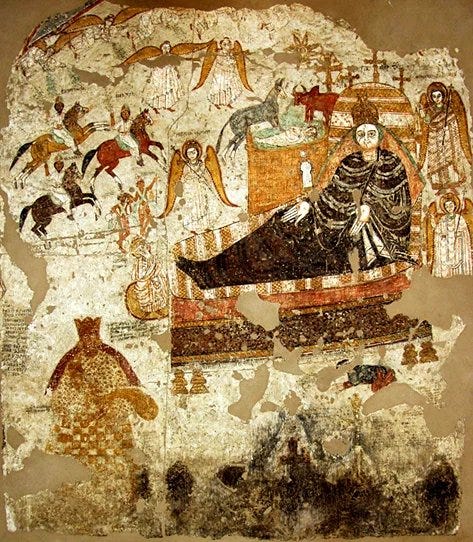

10-12th century wall painting of the nativity scene from Faras cathedral, King Moses George is also shown in the bottom right.

12th century painting from Old Dongola depicting a financial transaction

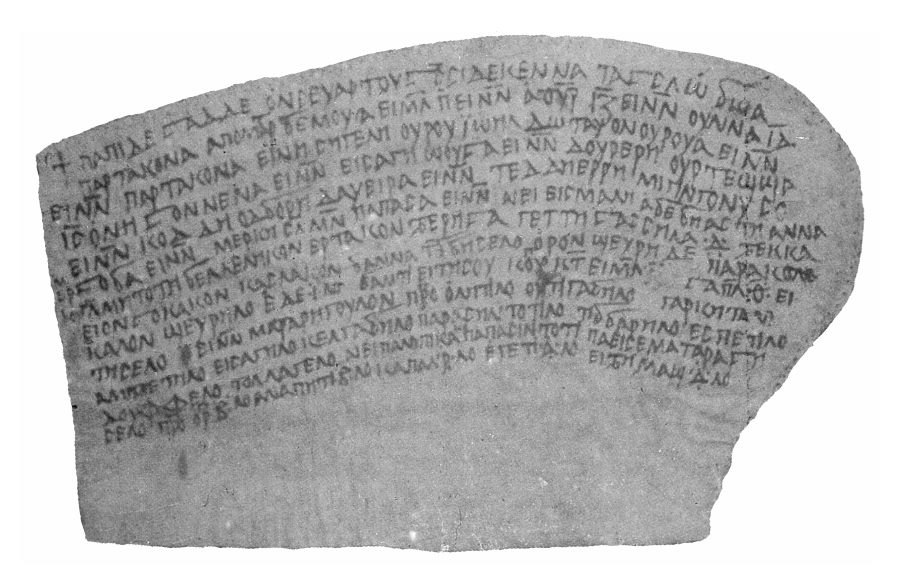

The robust literary tradition of Makuria which had by this time been sufficiently indigenized with extensive the use of Old Nubian script displacing Greek and Coptic in many textual works including the production of lengthy scribal masterpieces such as the Attiri book of Michael (an original 300-page codex written by a Makurian scribe under the patronage of the eparch)40 and a Coptic version of the book of Enoch, which had for long been assumed to be lost to the rest of the Christian world save for Ethiopia, thus providing further evidence of Nubia’s place in medieval Mediterranean ecumenism.41

Correspondence between Makuria and other African Christian states increased during this time, firstly was with the Coptic community of Egypt whose pope appointed the archbishops at Old Dongola, but the Nubian church was distinguished from its Ethiopian peer because the former retained the right to recommend its own candidates for the post of Archbishop of Old Dongola, who was taken from among its own citizens, attesting to the relative degree of independence of the Makurian church had that lasted even during its decline in the late 14th century.42

Makuria also had fairly regular contacts with Christian Ethiopian especially the kingdom of Aksum and the Abyssinian empire; in an 11th century account, an unnamed Ethiopian king sent a letter to the Makurian king Georgios II describing the deteriorating political situation of his kingdom which he interpreted as God’s punishment for the inappropriate treatment of the Abuna (the appointed head of the Ethiopian church) by previous rulers, and asked King Georgios to negotiate with the Patriarch Philotheos for the ordaining of a new Abuna. Georgios responded sympathetically to this request, sending a request letter to the patriarch who nominated Daniel as the new Abuna for Ethiopia. In the later years, other Ethiopians are noted to have travelled through Makuria on their way through Egypt (or from it) including an Ethiopian bishop who passed by the Makurian church of Sonqi Tino in the 13th century, and an Ethiopian saint who travelled through Makuria in the mid 14th century.43 A 13th century Ethiopian painting of a dignitary at a church in Tigray also depicts a Nubian visitor who may have come from Makuria or Alodia.

Fragments of the “Attiri Book of Michael” written in Old nubian

13th century Ethiopian painting of a Nubian dignitary from the Maryam Korkor church

Fatimid travelers and embassies were also sent to Makuria, the most famous was Ibn Salim al-Aswani in 970 who was sent by the Fatimid governor to Old Dongola and stayed in the capital for about six months, providing the most detailed account of the kingdom of Makuria (and its southern neighbor of Alodia) describing its “beautiful buildings, churches, monasteries and many palm trees, vines, gardens, fields and large pastures in which graze handsome and well-bred camels”44 this account was later collaborated by Abu salih writing before 1200, he was an Armenian chronicler in Egypt who described Old Dongola as "a large city on the banks of the blessed nile, and contains many churches and large houses and wide streets. the king's house is lofty with several domes built of red-brick and resembles the buildings in iraq"45, these descriptions match those of earlier writers such as Ibn Hawqal in the mid 10th century (who didn’t visit Old Dongola but did visit its southern neighbor Alodioa) and the recent archeological discoveries of the medieval Makurian cities and monuments in Sudan.

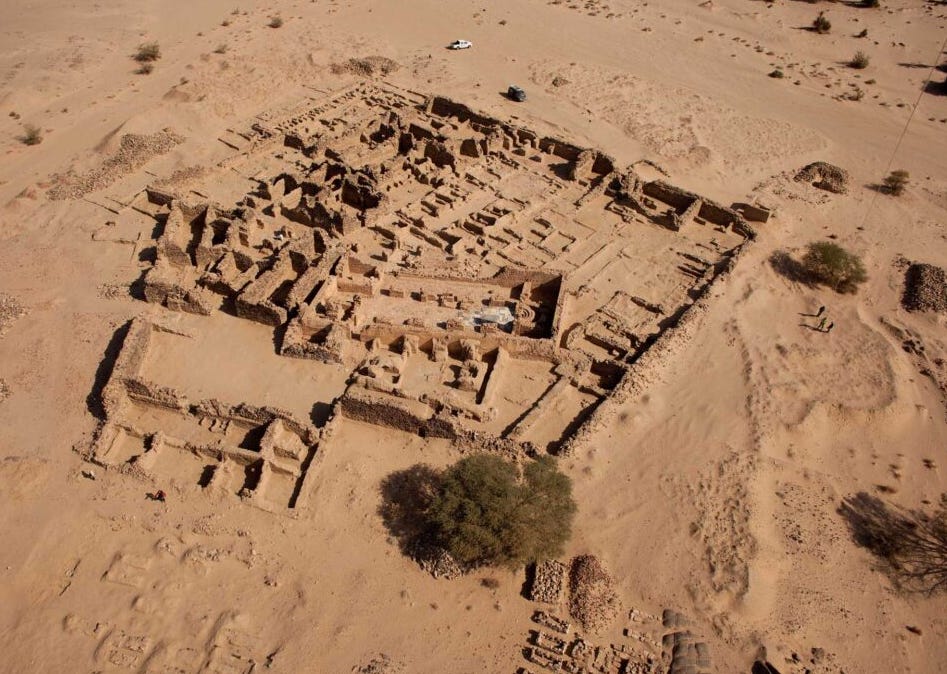

The monastery of el-Ghazali, built in the 7th century and occupied until the late 13th century

The church of st. Raphael at Banganarti, originally built in the 7th century and reconstructed over the centuries until the late 13th century when it became a major pilgrimage site.46

Makuria and the Ayyubid Egypt (1171-1250): An uneasy peace and the coming of the crusaders

The rise of the Ayyubid Egypt heralded the end of the cordial relations between Muslim Egypt and Makuria, the new foreign policy of the Ayyubids towards Makuria was colored by the political and religious upheaval brought about by the crusader invasions of Egypt in the 12th century. The crusaders had taken over the holy lands of the near east (the region from Sinai to Syria) and succeeded in establishing four crusader states, among which, the kingdom of Jerusalem (1099-1291) which directly bordered the Fatimids, was the most powerful. While Egypt had previously been peripheral to crusader concerns, it became the primary target of various Christian European armies with the beginning with Amalric of Jerusalem in 1163 and continued with several attacks that lasted for nearly a century, these attacks coincided with the decline of Fatimid power with the ascendance of child-kings between 1149 and 1160 the ultimately led to the rise of powerful military officials who ruled with full authority. One of these military officers was Saladin who became wazir (a vizier) of the last Fatimid caliph Al-Adid, in 1169, Saladin then begun expanding his power at the expense of his caliph by weakening the caliph’s army and strangling its revenues, these actions prompted the army to revolt and the African infantry soldiers, led by Mu'tamin al-Khilafa sought an alliance with the crusaders, this conspiracy that was uncovered by the Saladin who crushed their revolt, leading to the soldiers fleeing to upper Egypt, allowing Saladin to seize power in 1171 following the death of the caliph al-Adid.47

The conspiracy to ally with the Frankish crusader armies to overthrow Saladin also included Nubians from Makuria, and when the remnants of the african soldiers he had defeated retreated to upper Egypt, they attacked the city of Aswan in alliance with (or support from) the Makurians, Saladin sent an army under Shams ad-Dawla who then sacked Qasr Ibrim in 117348 Shams then sent a messenger to negotiate with the Makurian King Moses George demanding that he submit to Saladin’s authority and convert to Islam but the king is said to have "burst into wild laughter and ordered his men to stamp a cross on the messenger's hand with redhot iron”49 Frustrated with the collapse in negations, Shams tortured the bishop of Qasr Ibrim for money but "nothing could be found that he could give to shams ad-daulah, who made him prisoner with the rest", Shams would later award Ibrim in fief to a soldier named Ibrahim al-Kurdi but this only lasted a two years aftewhich al-Kurdi drowned in the Nile and his soldiers abandoned the city which reverted back to the Makurians. King Moses George continued to rule for nearly half a century50 until his abovementioned pilgrimage through the holy lands and Europe, Makuria itself maintained an uneasy but rather quiet relationship with Ayyubid Egypt until its fall to its own Mamluk slave soldiers in the late 1240s, which happened at a critical time during the invasion of Egypt by the seventh crusade.

Interlude: Makuria and the Crusader states

The late 1240s also mark the beginning of a concerted effort by Christian European kings to establish relations with the Makurian kings through their crusader offshoots, initially these were missionary efforts since the Miaphysite church of Alexandria which was followed by the Makurians, had existed in opposition to the roman catholic church of the western Europeans, Pope innocent IV thus called for a general council that met in Lyon in 1245 where he issued a papal bull that delegated Franscian friars to several Christian states urging them to join the Roman catholic church, one of their countries of destination was Makuria, he also dispatched emissaries with letters to the Makurian rulers (among other Christian kings) with the same instructions.51

While little is known about the letter reaching its intended recipients at Old Dongola, the discovery of a 13th/14th century graffito written in the Provençal dialect of southern France, at the Makurian city of Banganarti (which is less than 10 km from Old Dongola) attests to a direct contact between Christian Europe and Makuria by this time, and by the early 14th century, Genoese merchants were already active at Old Dongola.52

In the late 13th century, plans were being made by the crusaders that explicitly included a proposed alliance with the Makurians to split the forces of the Mamluk Egyptians, especially after the latter’s defeat of the Kingdom of Jerusalem in 1291 (the last of the crusader states to fall), and several of these proposed military alliances between Makuria and the crusader armies were presented to the Pope clement V in 1307 and to Pope John XXII in 1321.53 But the Mamluks were aware of the threat such an alliance would bring and worked to stifle any contact between the Nubians and the crusaders, and Mamluk sultans became more active in the succession struggles in Makuria with the intent of undermining its power.

Barely visible graffito scratched onto the walls of the Bangnarti church by a visitor from provance, this 4cm text is one of the oldest Latin inscriptions in sub-Saharan Africa, the more visible inscriptions below it, written in Greek and old Nubian were inscribed by local Nubian pilgrims54

14th century painting of a battle between the crusaders and the Muslim armies (Bibliotheque Nationale, Paris, France)

Makuria and the Mamluk sultanate of Egypt (1250-1517): warfare, decline and the end of Christian Nubia.

Its within the above mentioned context that the Mamluk policy towards Makuria turned decidedly hostile, But the Makurians themselves had already understood the threat the Mamluks posed and In 1268, the Makurian king David sent messengers to the Mamluk sultan Baybars about his deposition of the previous king whom he claimed was blind and that he had expelled him to al-Abwab (a small state between Makuria and Alodia). The Mamluk red sea trading interests also posed a threat to the Makurians, especially the port of Aidhab which had since grown into the principal port of the region at the expense of the southern ports of Badi and Suakin both of which allowed the Kings of Makuria and Alodia access to the sea.55

In 1182/3, the crusader armies under Renaud de chatillion attacked Aidhab (not long after Shams had attacked Qasr Ibrim in 1173), but the town had recovered56 and in 1272 the Makurian armies of king David attacked the same town as well as the city of Aswan and killed the governors stationed there, this promoted a retaliation from the Mamluk armies a few months later who attacked the city of Qasr Ibrim.57

In 1276, A disgruntled nephew of King David named Shekanda arrived at the sultan's court, claiming the throne of Nubia and requesting assistance from the Baybars to reclaim his throne in exchange for Shekanda meeting the baqt requests, the Mamluks then invaded Makuria a few months later, sacking Qsar Ibrim where they killed Marturokoudda, the eparch of Nobadia and a prominent local landowner, they then advanced south to Old Dongola (which was the first time Muslim Egypt’s armies had fought on Nubian soil in the 600 years since their defeat in 652), this time the battle ended with a Makurian defeat as David's divided forces couldn't withstand the Mamluk forces and he was captured and imprisoned not long after.

Shekanda was the enthroned as King of Makuria, but the Mamluk sultan Kalavun (the successor of Babyars) now considered Makuria only as a province of his Mamluk sultanate as he made clear in his negotiations with King Alfonso of Aragon in 1290 in a treaty that explicitly describes Kalavun describes himself as the “sultan of Makuria , the territory of David”58 this last emphasis was most likely added to suppress any attempts of the crusaders to form an alliance with the Makurians. The Mamluk army under would in the same year prepare for a siege of Acre and they ultimately defeated the forces of the crusader kingdom of Jerusalem in 1291, taking the remaining Frankish footholds on the coast (Tyre, Sidon, Beirut, Haifa) and ending Christian Europe's permanent presence in the holy lands.59

Before preparing the siege of Acre however, the sultan Kalavun had been involved in the succession disputes in Makuria where another disgruntled claimant appealed to him for military assistance to recover his throne which he claimed had been seized by the then reigning King Shamamun (Simeon), who was his maternal uncle. Kavalun sent an expedition in 1287 to take Old Dongola but Simeon retreated with his army and also informed his eparch/governor of Noubadia, Gourresi, to retreat, but the latter was captured by the Mamluks and turned to their side, allowing Kavalun's army to install Simeon's nephew to the throne and Gourresi as his deputy. Soon after the Mamluk forces returned to Egypt, Solomon re-emerged and deposed his nephew in 1288, the deposed nephew and Gourresi fled to Cairo to report this, which prompted Kavalun to send an even larger army in 1289 to reinstall the deposed nephew, but since the latter died on the journey, a son of David was chosen instead, Simeon retreated again and allowed the installation of the puppet but after the Mamluks had returned to Cairo in 1290, Simeon deposed their puppet, killing him and Gourresi. Simeon's rule continued unabated till his passing between 1295-129760, he is said to have sent his share of the baqt to sultan Kavalun after assessing that the latter was tired of installing weak rulers to the Makurian throne, and this is perhaps the earliest mention of a baqt payment and it consisted of 190 slaves61.

Simeon was succeeded by King Ayay who reined until 1311 or 1316, he sent two embassies to the Mamluk court in 1292 and 1305, explaining his failure to pay the baqt obligation, offering small customary present of camels instead of slaves, he also requested military assistance against the Arab incursions in upper Egypt which had for made the region insecure for the Mamluk sultans but had also begun extending their predations south to the northern regions of Makuria62 Ayay was succeeded by his brother King Kudanpes likely after a palace coup, the latter travelled to the Mamluk court in the following year likely to deliver a baqt and is said to have brought about 1,000 slaves as payment for decades worth of arrears.63 (this was the last recorded baqt payment by the Makurians)

But Kudanpes wasn't secure on the throne and his claim was again challenged by his nephew Barshanbu, a son of King King David's sister who had grown up in Cairo and had since converted to Islam, Barshanbu requested the Mamluk sultan Al-Nasir to grant him forces and install him at Old Dongola, to which King Kudanpes responded by nominating his own Muslim nephew Kanz al-Dawla to the sultan as a better alternative, but the latter was detained by al-Nasir who then sent a force to depose Kudanpes and install Barshanbi which was accomplished in 1317; whereafter the administrative building at Old Dongola was converted to a mosque (this is the first mention of a mosque in Makuria). Soon after his installation however, sultan Al-Nasir released al-Dawla who then deposed Barshanbu and reigned as king of Makuria. Still unsatisfied with the continued Makurian independence, sultan al-Nasir released the deposed king Kudanpes in 1323 to depose al-Dawla but this ended in failure64

Kanz al-Dawla was however the only Muslim ruler of Christian Makuria until its fall in the 15th century, and all of his known successors are mentioned to be Christian, as the reign of King Sitti in the 1330s indicates a restoration of Makuria's prominence with a firm control over the northern provinces as well as its capital Old Dongola, and Makurian institutions seemed to have successfully weathered the turbulence of the earlier decades quite well.65 although a number of monasteries had been abandoned by this time.66

Plaque in the administrative building at Old Dongola commemorating its conversion to a mosque in 1317

14th century painting depicting a Makurian royal under the protection of Christ and two saints.This may be the last painting of a Makurian king 67

The internal tension of the late 13th and early 14th century should not lead us to imagine Nubia heading into a rapid decline, as Makurian literacy, arts and construction appear to continued in the 14th century and 15th century.68 Internal strife returned in the 1365 as another king was yet again challenged by his nephew, the latter of whom reportedly formed alliances with the Banu Kaz, (a mixed Arab-Beja tribe that had over the 14th century come to control much of the red sea region including the port of Aidhab and challenged both Mamluk and Makurian authority in their eastern regions) the usurper seized Old Dongola forcing the reigning king to retreat to his new capital called al-Daw from where he requested the Mamluk armies aid him in his war, the Mamluk forces defeated the usurper who agreed to become the eparch at Qasr Ibrim under the reigning Makurian king, but Old Dongola was abandoned permanently after serving 800 years as the capital of Makuria.

The Makurian state nevertheless persisted and a Nubian bishop named Timotheos is appointed in the 1370s to head its church, little is known about Makuria in the succeeding years, the constant predations of the Banu Kaz and the Beja on the red sea ports and eastern regions remained a looming threat, and had prompted the Mamluk sultan Baybars to sack Aidhab in 1426 and the town was permanently abandoned69. In 1486 Makuria is ruled by King Joel who is mentioned in local documents, which attests to the relatively seamless continuity of Nubian legal practices and traditions in the late 15th century; eparch still govern Makuria’s northern province of Noubadia and Bishops (now stationed at Qasr Ibrim) are still present throughout the same period.70

By the turn of the 15th century, Makuria only existed as rump state, in 1517 Mamluk Egypt fell to the Ottomans and in 1518, Ali b. Umar, the upper Egypt governor of Mamluks who had turned to the Ottoman side is mentioned to have been at war with the “lord of Nubia”71, the old kingdom of Makuria limped on for a few years and then slowly faded to obscurity.

leather scroll of a land sale from 1463 written in Old Nubian, found at Qsar Ibrim

Conclusion: Makuria as an African medieval power

A closer inspection of the history of the relations between Makuria and Muslim Egypt throughout the millennia of Makuria’s existence reveals a dynamic that upends the misconceptions in the popular accounts of medieval north east Africa.

The kingdom of Makuria is shown to be a strong, stable and centralized power for much of its existence outlasting 6 Muslim Egyptian dynasties, it consistently represented a formidable challenge to centralized Egyptian authority. Its dynastic continuity relative to the various Muslim dynasties of Egypt also serves as evidence of Makuria's much firmer domestic political position which enabled it to dictate the terms within which both states conducted their relationship; for more than 600 years after the initial Muslim advance onto Nubian soil, it was Makuria which fought on Egyptian soil with several recorded battles in every century of its existence against each Egyptian dynasty (save for the Fatimids). Makuria’s elites were actively involved in Egyptian politics, and the strength of Makuria's army became known to the crusaders as well who devised plans to ally with it against a common foe, all of which indicates a balance of power strongly in favor of the Makurians and quite different from that related in al-Maqrizi's 15th century account, as the historian Jay Spaulding writes "Present Orientalist understanding of the baqt thus rests largely upon a single hostile Islamic source written eight hundred years after the events it purports to describe…The baqt agreement, from a Nubian perspective, marked acceptance of the new Islamic regime in Egypt as a legitimate foreign government with which, following the unfortunate initial encounter, normal relations would be possible"72

Even after the Mamluks succeeded in turning the balance of power against the Makurians, their attempt at interfering in Makurian politics was ephemeral, its institutions, particularly the Makurian church, remained a powerful factor in the royal court eventually restoring the Christian state until its gradual decline a century later. The largely hostile relationship between the Makurians and Muslim Egypt reveals that it was military power that sustained Makuria’s independence rather than a special status of peaceful co-existence as its commonly averred.

This is similar to the relationship between the early Muslim empires and the Kingdom of Aksum, the latter of which is often assumed to have been “spared” by the Arab armies (as per the instructions of Prophet Muhammad) but evidence shows that Aksum was the target of several failed Arab invasions beginning in 641, just 9 years after the prophet’s death, and their defeat by Aksum’s armies is what secured the kingdom’s independence73; sustaining it and Makuria as the only remaining Christian African states of the late medieval era.

the 7th century Makurian church of Qasr Ibrim

Read more African history on my patreon

The Oxford Handbook of Ancient Nubia by Bruce Williams pg 760, 808-810

The Rise of Nobadia by Artur Obłuski pg 199)

Ancient Nubia by P. L. Shinnie pg 123)

The power of walls by Friederike Jesse pg 132)

The Nubian past by David Edwards pg 249)

Medieval Christian Nubia and the Islamic World by Jay Spaulding pg 584)

Medieval Christian Nubia and the Islamic World by Jay Spaulding pg 578

Was King Merkourios (696 -710), an African 'New Constantine', the unifier of the Kingdoms and Churches of Makouria and Nobadia by Benjamin C Hendrickx pg 17-18)

The Oxford Handbook of Ancient Nubia by Bruce Williams pg 762)

The Rise of a Capital: Al-Fusṭāṭ and Its Hinterland by Jelle Bruning pg 106-7

The Oxford Handbook of Ancient Nubia by Bruce Williams pg 763),

Ancient Nubia by P. L. Shinnie pg 125)

Medieval Christian Nubia and the Islamic World by Jay Spaulding pg589)

The Archaeology of Medieval Islamic Frontiers pg 112

The Rise of a Capital: Al-Fusṭāṭ and Its Hinterland by Jelle Bruning pg pg 106-7)

The Oxford Handbook of Ancient Nubia by Bruce Williams pg 763

Medieval Christian Nubia and the Islamic World by Jay Spaulding pg 592)

Race and Slavery in the Middle East By Bernard Lewis pg 63-65

Possessed by the Right Hand by by Bernard K. Freamon pg 206-218)

Race and Slavery in the Middle East by Bernard Lewis pg 67-68

Across the Sahara by Klaus Braun pg 133-135

The Origin and Development of the Sudanese Ports by T Power pg 5, 7, 9)

The Origin and Development of the Sudanese Ports by T Power pg 10-12, 13-15)

The Archaeology of Islam in Sub-Saharan Africa by T. Insoll pg 103-105

The Rise of the Fatimids by Michael Brett

The Red Sea from Byzantium to the Caliphate by T power pg 157

Conflict and Conquest in the Islamic World by Alexander Mikaberidze pg 458

the nubian past by David Edwards pg 215)

The Medieval Kingdoms of Nubia by Derek A. Welsby pg 88-89

Medieval Nubia by G Ruffini p.248)

Ancient Nubia by P. L. Shinnie pg 129)

The Oxford Handbook of Ancient Nubia by Bruce Williams pg 765

The Oxford Handbook of Ancient Nubia by Bruce Williams pg 764)

The Fourth Crusade The Conquest of Constantinople by Donald E. Queller pg 140)

Medieval Nubia by G Ruffini p.252)

New discoveries in Nubia: proceedings of the Colloquium on Nubian studies, The Hague, 1979 by Paul van Moorsel pg 144)

Medieval Kingdoms of Nubia by D. Welsby pg 77)

Medieval Nubia by G Ruffini pg 262-264)

The Archaeology of Medieval Islamic Frontiers pg 105-114)

The Old Nubian Texts from Attiri by by Vincent W. J. van Gerven Oei

Medieval Nubia by G Ruffini pg 231)

Medieval Nubia by G Ruffini pg 255-256)

An Unexpected Guest in the Church of Sonqi Tino by Ochala pg 257-265

Nubia a corridor to Africa by W. Adams pg 461-462

Africa from the Seventh to the Eleventh Century pg 199

Banganarti on the Nile, An Archaeological Guide by Bogdan Zurawski

The age of the crusades by P.M. Holt pg 46- 51)

Medieval Nubia by G Ruffini pg 263-264)

Medieval Nubia by G Ruffini pg 249)

Medieval Nubia by G Ruffini pg 250-251)

The other ethiopia Nubia and the crusade (12th-14th century) by R Seignobos pg 309)

Medieval Nubia by G Ruffini pg 263-263)

The other ethiopia Nubia and the crusade (12th-14th century) by R Seignobos pg 310-312),

A man from Provance on the Middle Nile by Adam Łajtar and Tomasz Płóciennik

The kingdom of alwa by Mohi el-Din Abdalla Zarroug pg 86)

The Archaeology of Islam in Sub-Saharan Africa by Timothy Insoll pg 94-97)

The age of the crusades by P.M. Holt pg 133)

Early Mamluk Diplomacy (1260-1290) by by Peter Holt pg 132)

The age of the crusades by P.M. Holt pg 103-104),

From Slave to Sultan: The Career of Al-Manṣūr Qalāwūn by Linda Stevens Northrup pg 147-149)

Medieval Christian Nubia and the Islamic World by Jay Spaulding pg 592)

The age of the crusades by P.M. Holt pg pg 134)

Medieval Christian Nubia and the Islamic World by Jay Spaulding pg pg 592)

The age of the crusades by P.M. Holt 135)

Medieval Nubia by G Ruffini pg 29-30)

The Monasteries and Monks of Nubia by Artur Obłuski

The 'last' king of Makuria (Dotawo) by W Godlewski

The last king of makuria by by W Godlewski

The Archaeology of Islam in Sub-Saharan Africa by Timothy Insoll pg 97)

Medieval Nubia by G Ruffini pg 254-257)

The Medieval Kingdoms of Nubia Derek A. Welsby pg 254

Medieval Christian Nubia and the Islamic World by Jay Spaulding pg 585

The Red Sea from Byzantium to the Caliphate by Timothy Power pg 93

As someone that is Sudanese and is a big fan of Christian Nubia and Kush, thank you for this article. I believe this might be my favourite article you have published yet. This was extremely informative, it seems often in the internet Nubia's dominance in their relationship with Muslim Egypt and their relationship with European Christendom is overlooked and at times extremely downplayed. You have represented and told the history of Christian Nubia well.

Although I might sound like a nationalist when I say this but Sudanese history is amazing and need's more attention. Like seriously, from the Kushites being the most impactful in the Eastern Mediterranean in the 7-6th centuries BC to the classical fantasizations of the Kingdom of Kush to the strong and militant Nubian Christendom to the Funj and the Mahdiyya.

But honestly thanks for this article, I have read it over 6 times already.