Empire building and Government in the Yorubaland: a history of Oyo (1600-1836)

Why Africa's internal political processes explain African history better than external actors.

For over two centuries, the region of south-western Nigeria populated by Yoruba-speakers was home to one of the largest states in west Africa after the fall of Songhai.

The rise of Oyo empire as the dominant state of the Yorubaland owed much to its complex political structure, whose elaborate system of government that distributed authority among different institutions, enabled Oyo to project its power across a relatively vast region covering nearly 150,000 sqkm. The gradual evolution of these same political structures that enabled Oyo’s success, eventually led to the empire’s decline.

This article outlines the political history of Oyo from the rise of the empire to its collapse, including a description of its internal political organization, in order to explain why pre-colonial Africa’s internal politics explain the trajectory of Africa’s history better than external actors.

Map showing the maximum extent of the Oyo empire at its height in the late 18th century

Support AfricanHistoryExtra by becoming a member of our Patreon community, subscribe here to read more about African history, download free books, and keep this newsletter free for all:

Origins of Oyo; from the city-state to kingdom to empire. (12th-16th century)

The early history of Oyo is inextricably entwined with the settlement of the Yoruba-speakers in what is now south-western Nigeria and their creation of monarchical forms of government in this region between the late 1st and early 2nd millennium. The emergence of Imperial Oyo in the 17th century is predated by the establishment of the kingdom of Oyo during the 14th century around its capital Oyo-ile, which was itself first occupied between the 8th and 12th century.1

The city of Oyo-ile was at the center of the much of Oyo’s political and cultural history, and like many cities in the Yorubaland, Oyo's urban settlement was closely associated with political power. It consisted of a relatively dense but dispersed settlement pattern divided into the built-up area with its palaces, religious buildings, specialist workshops, houses, and the agricultural area, all of which were enclosed in a series of concentric system of walls and ditches as new additions were made after a significant increase in the city's population2. Covering over 52 sqkm, Oyo-ile was among the largest cities of west-africa due to the nature of its settlement which housed an estimated 100,000 at its height from the 17th and 19th century. Accounts from the 1820s described the city as a large cosmopolitan city surrounded by multiple walls over 20ft in height.3

Early in the 16th century, the kingdom of Oyo had been subjected in dramatic fashion to the influence of its northern neighbors in events that were distantly related to the political transformations that followed the displacement of the Mali empire by Songhai (whose power extended to Borgu/Ìbàrìbá in the north of the modern Benin republic) and the establishment of the Bornu empire west of lake chad (whose power extended to the Hausalands in northern Nigeria). Oyo was overrun by invaders from Nupe to its north-east, forcing parts of its royal dynasty to seek temporary refuge in Ibariba in the north-west and others to relocate their capital southwards to the city of Igboho, from where they eventually managed to defeat the Nupe.4

Oyo remained a state of minor importance until the early 17th century when its ruler Aláàfin Abípa re-established and resettled the old capital Oyo-ile. The state then underwent a period of expansion under Abípa's successors Obalokun and Ajagbo during which it extended its political influence southwards over large parts of the Yorubaland at an imperial scale, and greatly transformed its institutions of governance which were then spread across much of the region.5

Perimeter walls of Òyó-Ilé6

a few of the ruined sections of Oyo-ile’s walls still standing at just under 4 meters, the city was sacked and abandoned in the 1830s and most of its ruined structures quickly deteriorated in the humid climate

The government in Imperial Oyo: political intuitions in the 17th century

From the 17th century, Oyo had a system of government in which the power of the king, or Aláàfin, was balanced by the òyómèsì , a seven-person state council comprised of the heads of prominent lineages in the capital Oyo-ile that acted as a check on the Aláàfin’s power. Their offices in order of seniority were; Basorun, Agbakin, Samu, Alapini, Laguna, Akiniku and Asipa. They met with the Alaafin in the palace to make all laws and take the highest decisions of government including the election of a new Alaafin from a pool of royal candidates, and when dissatisfied with the reigning Alaafin could order his deposition by instructing him to take his own life.7

The Alaafin was in charge of approving the state's offices of administration and acted as the highest judicial authority, while the Basorun served as the commander of the army, who also nominated war chiefs serving under him called Eso, that supplied the cavalry forces of the army. Relations between the state council and the Alaafin were in turn mediated by the priestly leaders of the Ogboni cult of the earth of whom the state councilors were members but held little power over.8

Below these were several administrative offices and councils, especially the palace offices often populated by eunuchs, most notably; the Ona Efa (Eunuch of the Middle), the Otun Efa (Eunuch of the Right), and the Osi Efa ('Eunuch of the Left). Below the eunuchs were the ajele who were drawn from the palace by the Alaafin and appointed as provincial governors of Oyo settlements. Below these were the royal messengers called ilari, some of whom served as envoys to foreign kingdoms, relayed requests from the capital to the provinces, and collected tribute from vassal states.9

Within the army, the cavalry forces became the backbone of Oyo military strength and sustained its imperial expansion. While Oyo wasn't self-sufficient in horse breeding --being located along the margin of the tsetse-infested forest zone-- it could replenish its horses through trade with its northern neighbors, most notably the Nupe at the market town of Ogodo, as well as from Borgu and the Hausalands. Horses could survive in the northern provinces of Oyo where they were primarily kept and tended to by servants from the north (often Hausa), the latter of whom are also introduced horse-equipment to Oyo including horse-bits, saddles and stirrups.10

The Alaafin of Oyo and his officers on horseback, surrounded by attendants, National archives U.K, 1911

Strategies of Oyo expansion and settlement until the late 17th century

Oyo’s imperial expansion proceeded in a number of ways including; the creation of Oyo settlements in the frontier that were populated by loyal elites and subjects from the capital; the creation of client states through both diplomacy and warfare; and the creation of vassal states often through warfare. Oyo's authority was primarily expressed indirectly; in the Oyo settlements it was done through resident provincial governors who were inturn supervised by the royal messengers, in the client states it was done through the preexisting rulers (oba/king or baale/chief) that were approved by the Alaafin, and in vassal states it was exercised through the royal messengers who collected tribute11. For the core territories of Oyo, the system of government at the capital was repeated on smaller scale in the provincial towns from which taxes and duties were collected from traders in exchange for increased security through military protection. The expansion of Oyo utilized a mixture in the use of these different strategies.12

An example is in the upper-osun region that was contested between Oyo and the kingdom of Ilésà. The forces of Oyo moved against Ilesa during the reigns of 17th century Alaafins; Obalókun and Àjàgbó, ostensibly to punish Ilesa for brigandage activities in the region, but more likely to extend Oyo's hegemony over the emergent kingdom. This conflict ultimately ended with a stalemate as Ilesa was at best only a client state of Oyo, the latter of which was allowed by the former to establish an Oyo settlement at Ede-ilé.13 Recent archeological excavations indicate that the 82ha town of Ede-ile was established in the early 17th century, the presence of Oyo-ile ceramics, spindle whorls, cowries, as well as iron and cloth dyeing workshops, horse remains, and baobab trees indicate that the town was established by settlers from Oyo-ile.14 Similar Oyo settlements were established across the empire including as far north as at Okuta and as far south as at Ifonyin in Egbado.15(see blue lines on the map below)

Conversely, Oyo's attempts at military-driven expansion during this early stage produced mixed results. Its attempts to conquer regions to its south-east especially in Ijesha, during the reign of the Alaafin Obalókun, were met with defeat when the cavalry forces failed to take the forested regions; "the Oyos being then unaccustomed to bush fighting".16 Oyo's forces saw better success northwards in parts of Borgu approaching town of Bussa, as well as in the north-east where the towns of Ògòdò and Jebba were taken from the Nupe and westwards where it established suzerainty over Sábe kingdom.17

Oyo’s most important institutions crystalized during this period (in the 1st half of the 17th century). Most of these changes were influenced by the decisive role played by the alliances made between the exiled Oyo dynasties of the 15th century and the various groups which harbored them18. These included the elevation of the office of the state council’s leader the Basorun who was also the head of the army and often of Ibariba origin, and the Alapini was from the allied Nupe factions.19 But to counteract the power of the state council and to discontinue personal command of the army, the Alaafin Ajagbo also instituted the title of Are ona Kakamfo, who served as the commander-in-chief of the provincial forces.20

The long reign of Alaafin Ajagbo which ended in the late 1680s was followed by a succession of 9 short-lived rulers who were often deposed by the state council, and their campaigns of expansion were mostly unsuccessful. This period produced the first recorded instance of an Alaafin (Odarawu) being forced by the council to abdicate and take his life, the first instance of Oyo's army storming its capital to fight its own Alaafin (Karan) after he deposed the council, and the increasing importance of the crown prince's office called Aremo. This interregnum of internal political turmoil in Oyo ended with the ascension of Alaafin Ojigi in the mid-1720s, who is credited for Oyo's greatest expansion.21

Map showing the settlements and military conquests of Oyo between the 17th and 18th century

The era of military expansion in the early 18th century

For its south-western expansion, Oyo utilized a mix of diplomacy and military intimidation, enabling it to turn the kingdoms of Sabe and Kétu into client-states by the early 17th century, and opening the way for a further expansion south into the Egbado polities by 1625 (shown as 'Gbado' in the map above). Oyo settlements were also established in this region at Ìlarò, and Ifonyin among others, of which Ìlarò became the most dominant under its founder Òrónà who extended political control over several polities and communities in the region.22 The governors of these Oyo settlements were were typically recalled to the capital after serving 3 years, but by the late 18th century were required to abdicate office upon the ascension of a new Alaafin.23

Further westwards, Oyo expansion relied almost entirely on military conquest. The extension of Oyo's political influence over the rest of Egbado between the 1670s and 1680s had brought it into conflict with the kingdom of Allada, a powerful state whose vassals included Wydah and Dahomey. After some internal political conflicts in Allada, a group of its subjects travelled to Oyo-ile in 1698 and petitioned the Alaafin to intervene against their King's "mis-governance", to which the latter sent envoys to the king of Allada who promptly killed them. Oyo's cavalry invaded Allada in 1698/9 and overrun its capital forcing its king to flee and loosening Allada's suzerainty over its vassals Dahomey and Whydah, but Oyo didn't consolidate its victory over Allada.24

Succession disputes in Allada following Oyo's invasion further degraded its internal politics. A dispute between King Soso of Allada and his brother Hussar, saw the latter seeking the aid of king Agaja of Dahomey to install him, while Soso averted this alliance by allying with Whydah in 1722, this proved ephemeral as Agaja invaded Allada in 1724. Agaja took up residence in Allada's capital, forcing Hussar out.25 Hussar, fled to Oyo-ile and petitioned Alaafin Ojigi to intervene, who then dispatched a cavalry force which invaded and defeated Agaja's army in Allada in May 1726, forcing the king of Dahomey to flee from the capital. But Oyo's forces withdraw shortly after since the horses couldn't survive long in the region, and Agaja re-occupied Allada's capital, leaving Hussar an exile in Whydah. Agaja later conquered Whydah's capital Savi during march 1727 after a political conflict over trade customs with its king Hufon.26

While king Agaja's envoys had sent presents to the Alaafin's court to placate the latter's dreaded cavalry, but the deposed king Hufon of whydah appealed to Oyo for military aid to reinstall him in his capital Savi, even as Agaja was also offering Hufon his throne back in exchange for tribute. Hufon opted to ally with Oyo, which promptly invaded Dahomey's capital Abomey several times nearly every year from 1728-1732.27 In the first of the Oyo invasions led by the Basorun Yau Yamba in 172828, Dahomey’s king Agaja evacuated his capital and took his subjects into the forested regions which forced the Oyo armies to turn back, allowing him to return and rebuild. In the 2nd invasion of 1729, Oyo's forces dispatched units to hunt down Agaja in the forests and occupied Dahomey as long as they could (from May to July) to force them into submission29. Oyo's 3rd invasion of Dahomey in 1730 forced Agaja to negotiate; sending his prince (the future king Tegbesu) to Oyo-ile as a hostage, arranging a royal intermarriage, and gifting the Alaafin Ojigi with many presents/tribute30

Ojigi also sent Yau Yamba to the eastern frontiers of the empire into the region of Ibolo during the early 1730s. This campaign used the Oyo settlement at Offa as the launching ground for the campaign, but Oyo’s forces were withdrawn after their commander had fallen with his horse.31 Back at the capital, the increased power of Ojigi's crown-prince was strongly opposed by the state council, they therefore instructed both Ojigi and the Aremo to take their life in 1830, and greatly reduced the office of the crown prince.32

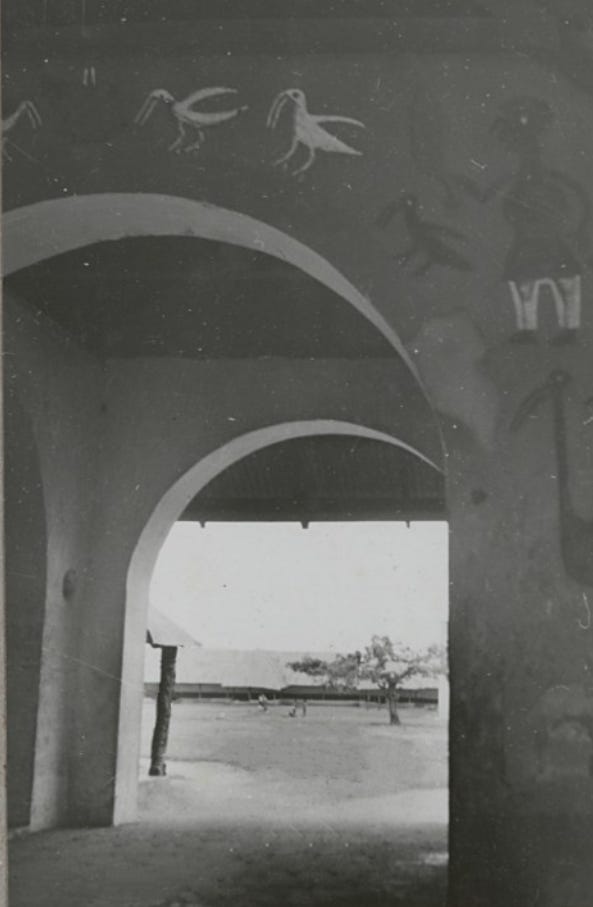

Entrance to Dahomey’s king Behazin's palace in Abomey, Benin republic, showing the ruins of King Agada’s palace that was built around 1720, photo from quai branly

The era of consolidation in the mid 18th century

Ojigi was succeeded by a relative weak Alaafins; Gberu and Amuniwaiye who were unable to counter internal opposition from the state council. The former attempted to influence the council by appointing an allied lineage head named Jambu as the Basorun, but the two didn't get along and both eventually took their lives the latter after the former. Alaafin Amuniwaiye didn't fare any better, being compelled to eliminate the deceased Basorun Jambu's allies in the council before he was himself forced to take his life.33

The campaign against Dahomey in 1730 had reduced the Mahi kingdom (sandwiched between Dahomey and Oyo) into a vassal state that allied with Oyo against Dahomey. Agaja retaliated by besieging Mahi's capital Gbowele in 1731-2 and ceasing the payment of tribute to Oyo, but internal circumstances after Alaafin Ojigi's death in 1730 (exlained above), prevented Oyo from invading Dahomey.34 The ascension of the more capable Alaafin Onísílé in 1746 altered Oyo's relations with Dahomey and the latter was invaded in 1742 and 1743 forcing the king Tegbesu to retreat from Abomey which along with the city of Cana was burned by Oyo's cavalry before they withdraw. Between 1745-7, Tegbesu tried placating Oyo with gifts but neither of the kings could agree on the amount of tribute to be paid, and in 1748 Oyo's forces invaded Dahomey and forced Tegbesu to flee, before the latter negotiated a higher tribute that was acceptable to Oyo.35

However, Onisile was instructed to take his life by the state council after an act of sacrilege to his palace, its during this time that the Basorun Ga (also spelt Gaa/Gaha) rose to prominence. After Onisile, two Alaafins reigned in close succession; Labisi (r. 1754), Awonbioju (r. 1754) and they were both deposed after being compelled to take their lives by Ga who increasingly subjected the crown and government to his personal rule.36 Alaafin Awonbioju was succeeded by Alaafin Agboluaje (r. 1754-1768) who managed to survive relatively longer than his predecessors because he submitted to Ga's authority. As the Basorun, Ga had a lot of influence which was enhanced by the circumstances of his rise, he took over collection of tribute and customs from the settlements and provinces using his sons instead of the royal messengers, and reduced the Alaafin to receiving a stipend. Ga was likely an expansionist and he requested the Alaafin Agboluaje to attack the vassal ruler of Ifonyin (the Oyo settlement) named Elehin-Odo, but when the Alaafin refused, Ga instructed him to take his life. Atleast one frontier war occurred under Ga in 1764 when an Oyo army stationed in the area of Atakpame (modern Togo) defeated an Asante army (from modern Ghana).37

Oyo under Ga underwent a period of consolidation during when there were no major additions to the empire. Its during this time that Dahomey remained a loyal vassal state paying tribute annually and contining to do so for over 70 years (1748-1818/23). Some Oyo institutions were adopted by Dahomey including royal seclusion, use of eunuchs in offices, as well as messengers (wensagon/lari), and the master of the horse (sogan). Unlike Oyo's more proximate provinces, these institutions weren't introduced to Dahomey by Oyo settlers (since the Oyo messengers only came to collect tribute at Cana) but by the Dahomean elite to enhance their own power.38

The Alaafin Agboluaje was succeeded by Alaafin Abíódún, who bid his time to overthrow the Basuron Ga by raising forces of loyal supporters in the provinces that were opposed to the conduct of Ga's sons. Around 1774, Ga instructed Abiodun to take his life after losing confidence in his short reign, but Abiodun rejected the instruction. The allies of Abiodun led by the provincial commander Oyabi of ajase, battled with Ga's forces who they later defeated and killed.39

The Oyo empire attained its greatest territorial extent under Abiodun with the formal integration of the small coastal polities centered at Badagry and Porto Novo.40 But Oyo's armies were less formidable at the frontier as they had earlier been, an invasion of Borgu in 1783 in order to suppress a rebellion was met with defeat41, and the Alaafin chose to rely on his dependencies notably Dahomey under Kpengla (1774-1789), whose armies were allowed by Oyo to attack other vassals like Badagry and Wèmè that were perceived to be rebellious, but were restrained from attacking loyal vassals like Arda.42

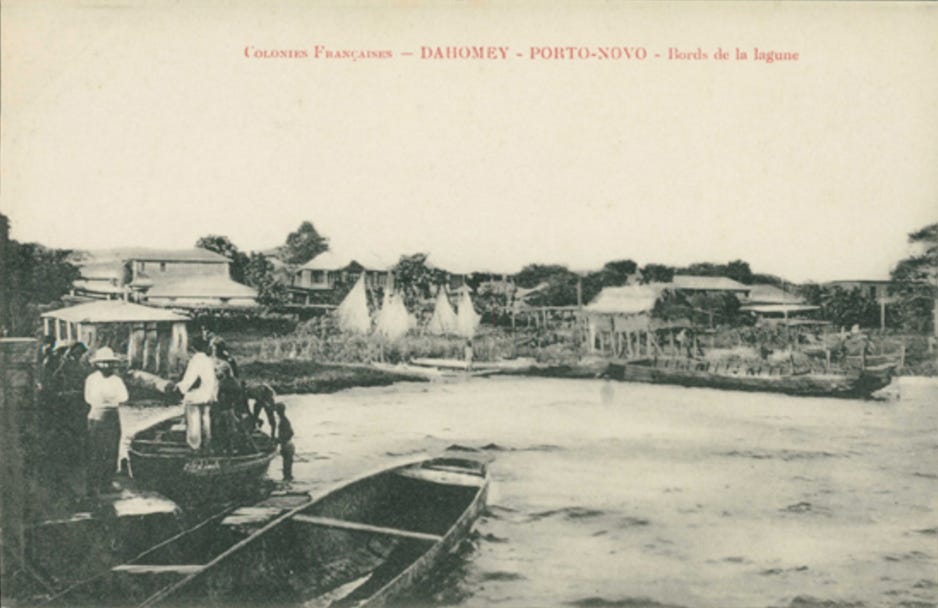

Porto-Novo in the early 20th century. The port settlement was established by exiled Allada royals, was called Àjàsé while under the Oyo empire (not to be confused with the similarly named Ajase of the governor Oyabi mentioned above)43

The domestic economy of Oyo during the 18th century

There were no major changes made in Oyo's political structure during the reign of Abiodun save for the formation of a short-lived standing army, and the prominence of the offices of the crown prince and provincial commander at the expense of the council. Oyo’s internal economic structure is best understood during this period. State revenues were collected from the extensive use of turnpike tolls, market levies, and taxes that were collected from the capital, the Oyo settlements in the provinces, and as tribute from the client states and vassal states. These taxes and tribute were primarily paid in cowries, but also in commodities such as cloth, and in tribute such as slaves, as well as horses and agricultural products.44

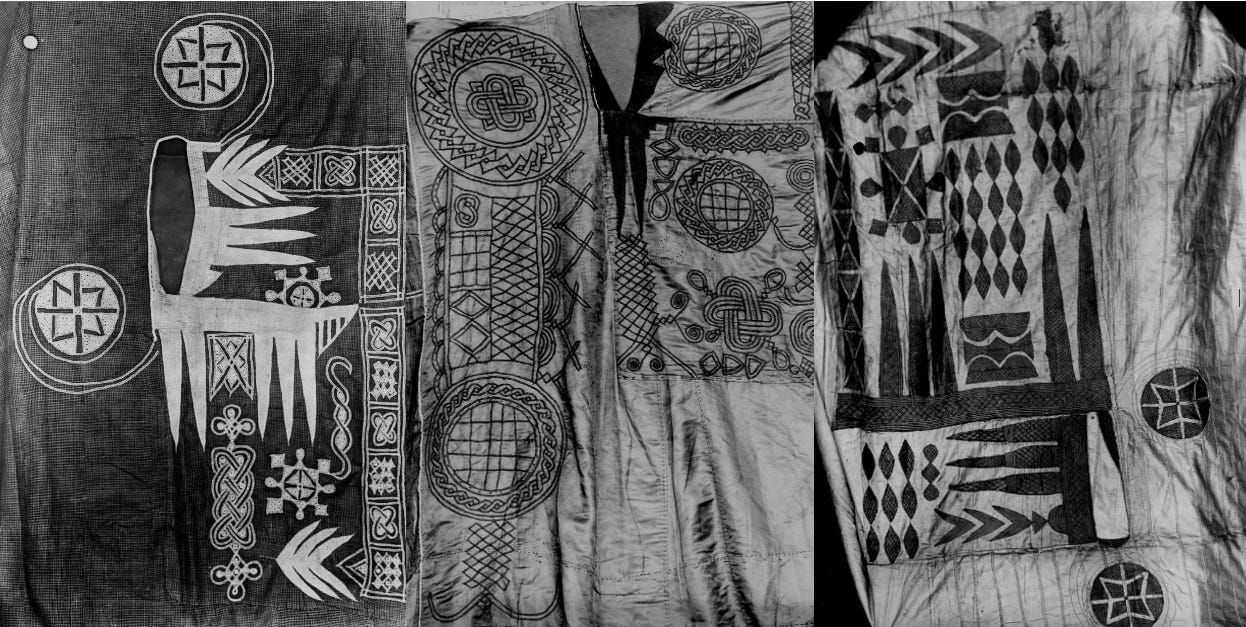

The bulk of Oyo's population —as in most pre-modern societies— was involved in agriculture, but there was also a substantial crafts industry employing specialist laborers who supplied local markets with domestic manufactures. The best described local industry was the production of embroidered and dyed textiles made from the various cotton and indigo fields whose cotton and dyes were worked by specialist weavers in towns across the empire as described by various visitors in the early 19th century. An external account of a visit to the town of Ìjànà in 1826 noted that it had “several manufactories of cloth.” and “three dye-houses, with upwards of twenty vats or large earthen pots in each,” all busy producing excellent indigo and “durable dye,” which formed an important capital in local trade. Other industries include leather goods, iron smelting, ivory and bronze casting, wood carving and pottery.45 (despite the internal turmoil of the early 19th century, explorer accounts of Oyo still describe an empire that was economically vibrant, generally peaceful, and safe for travelers46)

External trade southwards to the Atlantic coast increased during the 18th century when many of the ports in the ‘bight of Benin’ were under Oyo's suzerainty. Like all states along the Atlantic coast, captives from Oyo came from very dispersed sources and were often procured by private merchants, as the state was more focused on taxing trade (in general) rather than creating the supply.47 Since enslaving Oyo subjects was forbidden and often strictly enforced as long as the state was powerful enough to do so, private traders would purchase captives from frontier markets in the north, or would acquire those captured after war, or those enslaved locally or as punishment for crimes.48 Oyo's external trade northwards towards the Hausalands, Borgu and Nupe markets was primarily focused on the acquisition of horses, salt, natron, and captives, as well as manufactures such as leatherworks and dyed-textile clothing to supplement the locally manufactured products.49

Indigo-dyed cotton textiles from yorubalands, early 20th century, quai branly

Indigo-Dyed cotton wrapper from Oyo, early 20th century, British museum Af1991,14.1

Embroidered robes made from the city of Ilorin, late19th/early 20th century, State museum Berlin

Breakdown and collapse in the late 18th and early 19th century

The Alaafin Abiodun passed away in 1789 and the state council re-asserted their eroded power in opposition to the crown-prince Adesina who briefly reigned before he was instructed to take his life by the Basorun Asamu. The Alaafin Awólè was elected by the state council which hoped to influence his administration as he was perceived to be weak. But Awole clashed with Asamu over restitution of a Hausa trader's belongings, quarreled with the Owota (an Eso who was one of the top military officers) named Lafianu over an execution, and nearly committed an act of sacrilege by ordering an attack on the city of ile-Ife which harbored a rebel, his forces were also defeated by the Nupe in 1890-1.50

The most significant internal crisis under Awole was the increasing opposition from Afonja, who was the provincial commander and was based in the city of Ilorin. Afonja's grandfather Pasin and father Alagbin had fought in the revolts against the Basorun Ga leading upto 1774, and had been appointed to Ilorin by Awole to keep him away from the capital as Awole feared that Afonja harbored ambitions to succeed him. As relations between the two continued to sour, Awole ordered Afonja to attack the near-impregnable city of Iwere hoping to get rid of him, but Afonja organized a mutiny instead and allied with the disgruntled Basorun, the Owota and several other provincial nobles who besieged Alaafin Awole in Oyo-ile and instructed him to take his life, ending his reign in 1796.51 (This was the first instance of a Basorun -the head of the armies of Oyo- requiring military aid to depose an Alaafin)

The Empire begun its long decline following the death of Awole. The Egba provinces broke off in 1797 and Afonja's city Ilorin emerged as a rival center of power after he was betrayed by the Basuron who chose a different candidate as Alaafin because he feared the former’s strength. Afonja replaced many provincial governors in the central regions of Oyo with his own using his own army, during which time 3 Alaafins were elected in close succession between 1897-1802 and a failed attempt was made to dislodge Afonja from Ilorin when the Basorun organized a military alliance with mercenaries from Ibariba. A weak Alaafin Majotu (r. 1802-1830) was elected unleashed centrifugal forces across the empire as powerful vassal states such as Dahomey effectively became independent by 1818-1823, and Afonja's Ilorin fully seceded from Oyo and allied with Sokoto empire (which by then controlled the Hausalands). Effective power in the capital lay with the crown-prince Adewusi who briefly reigned after Majotu's passing in 1830 before he was removed by the Basorun.52

By the 1830s, the southern provinces of Egba were fully independent and the northern provinces of Oyo had been overrun by Sokoto’s forces —which also killed Afonja and seized Ilorin—. The last Alaafin of the Oyo empire fell in battle against the Sokoto forces in 1836 and the empire's old capital was abandoned, the kingdom was later reconstructed in a much reduced state with its capital at Ọ̀yọ́-Àtìbà (new-Oyo).

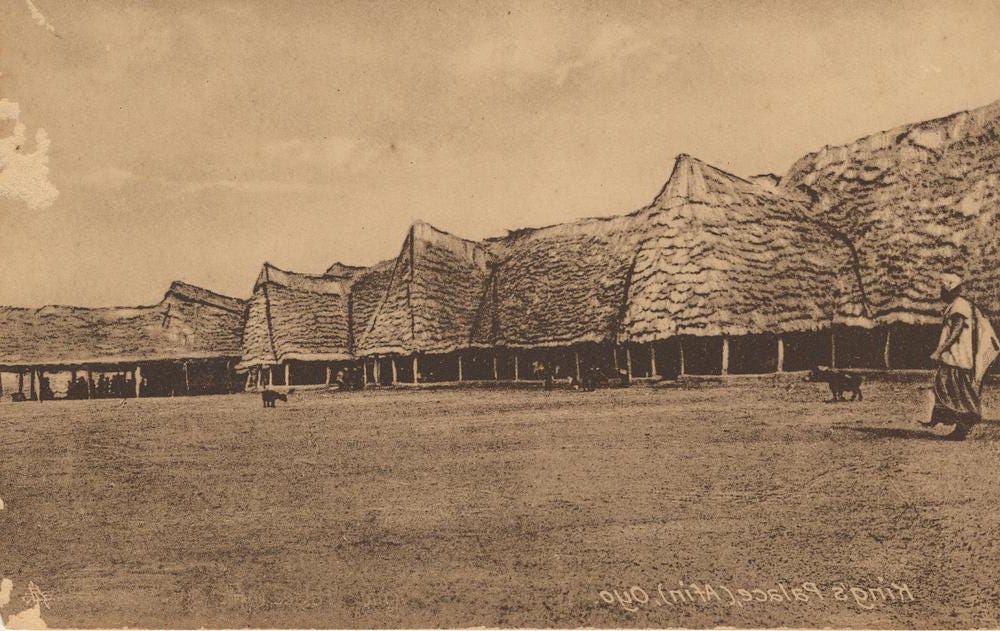

Alaafin's palace at new-Oyo, 1911, British museum

The government in Oyo, and how Africa’s internal political institutions determined African history.

The organization of power in the empire of Oyo provides an excellent example of the dynamic nature of political institutions in pre-colonial Africa that allows us to understand the evolution of social complexity within the African context.

Oyo's distribution of power between the Alaafin and the state council, was a product of the complex nature that enabled the empire's emergence through alliances between autochthonous and foreign elites.53 This form of distribution of power (which is also attested in a number of African kingdoms from the Hausa and Swahili city-states to the kingdoms of Kongo and Loango) enabled Oyo to overcome initial constraints in territorial expansion by providing it with a demographic and military advantage to establish distant settlements, and build up its formidable cavalry forces. But the equilibrium between the two institutions often shifted during transitional periods of military expansion and election of new Alaafins, and it gradually reinforced the state council's position against the Alaafin, who was inturn forced to secure his authority by creating an alternative military system using provincial nobles. The involvement of militant provincial nobles by the Alaafin could only be sustained when the center was strong, but when the center weakened so much that even the Basorun required military aid, provincial nobles (eg Afonja) used the opportunity to carve out their own states.

A similar evolution in government occurred in Kongo, where the shifting balance of power between the Kings, the state council, and the provincial nobles (the daSilvas of Soyo), which had earlier enabled the kingdom's expansion, eventually led to its disintegration. (Its not particularly unique to Africa either, since its a common theme in the rise and fall of empires across the world)

The government in Oyo is another case in which internal Africa political processes rather than external actors, provide us with a better understanding of African history in its local context. It was the evolution of political institutions of Oyo that enabled its expansion and decline; the trajectory of the Oyo empire did not depend on the ebb and flow of the Atlantic world’s economic demands, but on the internal political processes of the Yorubaland.

The view from Ọ̀yọ́-Àtìbà, 1953

During the ancient times; Africans travelled and lived in the Roman Europe just as Romans travelled into Africa; read about this and more in;

If you liked this article, or would like to contribute to my African history website project; please support my writing via Paypal

INCASE YOU HAVEN’T BEEN RECEIVING SOME OF MY POSTS IN YOUR EMAIL INBOX, PLEASE CHECK YOUR “PROMOTIONS” TAB, MOVE IT TO YOUR “PRIMARY” TAB AND CLICK “ACCEPT FOR FUTURE MESSAGES”. Thanks.

Revisiting old Oyo by C. A. Folorunso pg 8, Urbanism in the Preindustrial World by Glenn R. Storey pg 155)

African Civilizations: An Archaeological Perspective by Graham Connah pg 155-156)

Urbanism in the Preindustrial World by Glenn R. Storey pg 155-157)

The Yoruba: A New History by Akinwumi Ogundiran pg 163-173)

Kingdoms of the Yoruba By Robert Sydney Smith pg 34-35)

The Yoruba: A New History by Akinwumi Ogundiran pg 243

Kingdoms of the Yoruba By Robert Sydney Smith pg 36, The Constitutional Troubles of Ọyọ in the Eighteenth Century by R. C. C. Law pg 28)

The Constitutional Troubles of Ọyọ in the Eighteenth Century by R. C. C. Law pg 29-30)

A History of the Yoruba People by Stephen Adebanji Akintoye pg 262, The Constitutional Troubles of Ọyọ in the Eighteenth Century by R. C. C. Law pg 30-31)

A West African Cavalry State: The Kingdom of Oyo by Robin Law pg 4)

Kingdoms of the Yoruba By Robert Sydney Smith pg 37, The Yoruba from Prehistory to the Present by By Aribidesi Usman pg 128

Power and Landscape in Atlantic West Africa by J. Cameron Monroe, Akinwumi Ogundiran pg 242-243)

The Yoruba: A New History by Akinwumi Ogundiran pg 207-208)

Power and Landscape in Atlantic West Africa by J. Cameron Monroe, Akinwumi Ogundiran pg 239-240)

The Yoruba: A New History by Akinwumi Ogundiran pg 192

The Constitutional Troubles of Ọyọ in the Eighteenth Century by R. C. C. Law pg 10).

The Yoruba: A New History by Akinwumi Ogundiran pg 198)

This paragraph condenses two seemingly contradicting statements about the origins of the Basorun vs the Oyo dynasty, the former of whom is considered by some scholars to be autochthonous and that the latter was “foreign” resumably Ibariba or Nupe, see; Early Oyo history reconsidered by B. A Agiri pg 8-9

This contradicts with the footnote above by reversing the identities of the Basorun vs the Old oyo dynasty by using the names of the basorun to argue for their non-yoruba identity, see The Yoruba: A New History by Akinwumi Ogundiran pg 191-192

The Constitutional Troubles of Ọyọ in the Eighteenth Century by R. C. C. Law pg 31)

The Constitutional Troubles of Ọyọ in the Eighteenth Century by R. C. C. Law pg 30-32)

The Yoruba: A New History by Akinwumi Ogundiran pg 209)

The Cambridge History of Africa. Volume 4 pg 232)

The Kingdom of Allada by Robin Law pg 113)

The Slave Coast of West Africa, 1550-1750 by Robin Law pg 278-280)

Wives of the leopard by Edna G. Bay pg 58, The Slave Coast of West Africa, 1550-1750 by Robin Law pg 281-282, Ouidah by Robin Law pg 52)

Ouidah by Robin Law pg 53, Wives of the leopard by Edna G. Baypg 83)

The Cambridge History of Africa. Volume 4 pg 241)

The Slave Coast of West Africa, 1550-1750 by Robin Law pg 289-291)

Wives of the leopard by Edna G. Bay pg 53,64)

A History of the Yoruba People by Stephen Adebanji Akintoye pg 259)

The Constitutional Troubles of Ọyọ in the Eighteenth Century by R. C. C. Law pg 32)

The Constitutional Troubles of Ọyọ in the Eighteenth Century by R. C. C. Law pg 32-33)

The Slave Coast of West Africa, 1550-1750 by Robin Law pg 293-295)

The Slave Coast of West Africa, 1550-1750 by Robin Law pg 320-324)

Kingdoms of the Yoruba By Robert Sydney Smith pg 38)

The Constitutional Troubles of Ọyọ in the Eighteenth Century by R. C. C. Law pg 33-34, Kingdoms of the Yoruba By Robert Sydney Smith pg 38,

Wives of the leopard by Edna G. Bay pg 110-118)

The Constitutional Troubles of Ọyọ in the Eighteenth Century by R. C. C. Law pg 37)

The Constitutional Troubles of Ọyọ in the Eighteenth Century by R. C. C. Law pg 25-26)

Kingdoms of the Yoruba By Robert Sydney Smith pg 35)

A History of the Yoruba People by Akintoye, Stephen Adebanji pg 259)

The Constitutional Troubles of Ọyọ in the Eighteenth Century by R. C. C. Law pg 36, n47

The Yoruba: A New History by Akinwumi Ogundiran pg 263-264)

The Yoruba: A New History by Akinwumi Ogundiran pg 263-266)

A History of the Yoruba People by Akintoye, Stephen Adebanji pg 184

A History of the Yoruba People by Akintoye, Stephen Adebanji pg 264-5, 278-279)

The Yoruba from Prehistory to the Present by Aribidesi Adisa Usman pg 141-151)

The Yoruba: A New History by Akinwumi Ogundiran pg 243)

Kingdoms of the Yoruba By Robert Sydney Smith pg 39)

The Constitutional Troubles of Ọyọ in the Eighteenth Century by R. C. C. Law pg 39

The Constitutional Troubles of Ọyọ in the Eighteenth Century by R. C. C. Law pg 40-41

see footnotes 18 and 19 above

Great article and very interesting. I noticed small typos (though it is obvious in context the dates that are meant):

I think that in this paragraph you meant to type 1726 and not 1626: "Hussar, fled to Oyo-ile and petitioned Alaafin Ojigi to intervene, who then dispatched a cavalry force which invaded and defeated Agaja's army in Allada in May 1626, forcing the king of Dahomey to flee from the capital."

And I think that here you meant 1731-2:

"Agaja retaliated by besieging Mahi's capital Gbowele in 1831-2 and ceasing the payment of tribute to Oyo, but internal circumstances after Alaafin Ojigi's death in 1730 (exlained above), prevented Oyo from invading Dahomey."