Investigating Africa's historic links with the Old World: ancient DNA and autobiographical evidence from England.

In 2022, archaeologists working on a cluster of early medieval cemeteries near the southern coast of England found the remains of two individuals with West African ancestry whose burials were dated to the 7th century.

The two burials included: a 13-year-old girl from an early Anglo-Saxon cemetery at Updown in Kent with 33% West African ancestry from her paternal line (related to modern-day Mandinka and Yoruba), and a young man from a cemetery at Worth Matravers in Dorset with 25% West African ancestry (Gambia), also from his paternal line.1

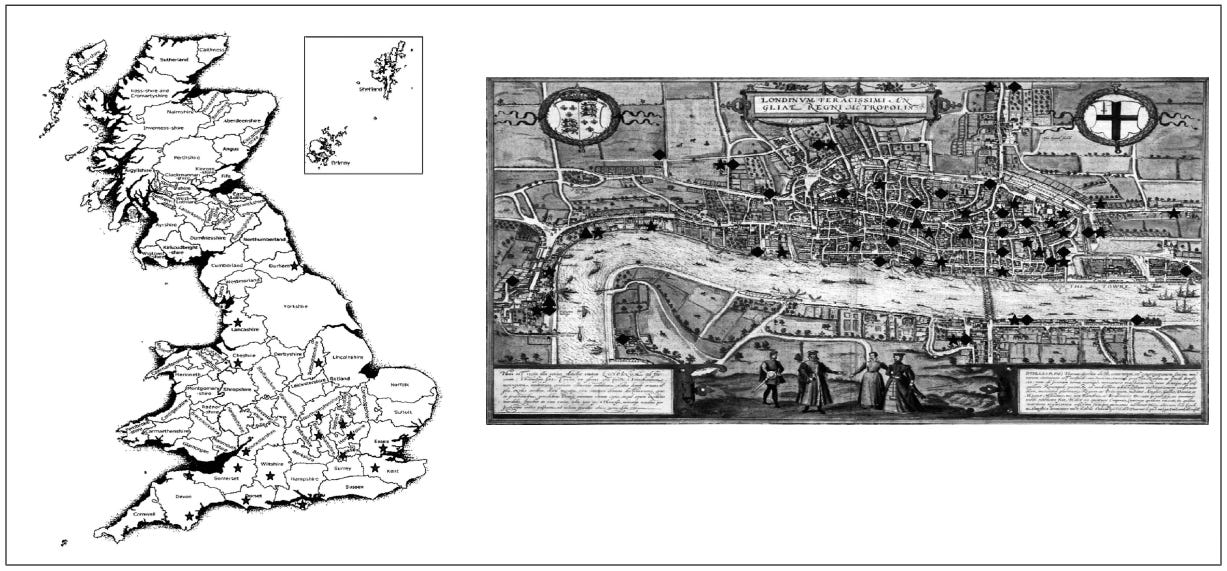

Location of the Updown and Worth Matravers cemeteries. Map by Duncan Sayer et al.

The two individuals, although unrelated, would have derived their ancestry from grandparents who were of full West African descent, having married into the local community during the early period of Anglo-Saxon migrations. The girl was buried next to her direct maternal relatives, all of whom had European ancestry. The young man's burial was also similar to that of the surrounding burials.

According to the excavators of the sites:

“The complete incorporation of Updown girl within her community and its customs strongly implies that her father, and potentially the deeper paternal line, was known to that community. Similarly, full social assimilation of the young man at Worth Matravers is arguably demonstrated through his sharing of a grave with an unrelated man with whom he shared some proportion of WBI [Western British Irish] descent.”2

These groundbreaking archaeological discoveries reveal the limits of our dependence on textual sources for investigating the historic links between Africa and the rest of the Old World.

While there’s sufficient documentary evidence for historic links between early medieval England, the Byzantine empire, and Africa3, none of the contemporary accounts provide specific references to West Africans in western Europe during this period.

Curiously, one of the earliest post-Roman accounts on African travellers in the Mediterranean world comes from the hagiography of the 8th-century Anglo-Saxon monk St. Willibald of Wessex, who was said to have met two ‘Ethiopians’ (Ethiops) near Jerusalem on his pilgrimage to the Holy Land in 722-729 CE.4

Pilgrims and envoys from the kingdoms of Nubia, Aksum, and Abyssinia/Ethiopia were a familiar sight in the eastern Mediterranean during the Middle Ages, and for most of the preceding Roman period. They were also present across southern Europe, from Italy to Spain, although evidence for this begins in the 12th century, by which time they were joined by West African Muslim travellers.

While there is plenty of textual evidence for Africans in Western Europe during the 15th and 16th centuries, especially in England, where they appear in multiple church and official records, their exact origins cannot be determined since most are assumed to have come from the Iberian Peninsula.5

(left) A partial representation of the locations of black people in Britain between 1500 and 1677, as indicated by documentary citations. (right) A partial representation of locations of black people in London between 1500 and 1677, as indicated by documentary citations.6

Detail of a Westminster Tournament Roll from 1511, showing an African trumpeter named John Blanke, who was active at the court of King Henry VIII in Tudor England.

16th-century painting showing an African knight of the order of Saint James of the Sword. Chafariz d’el Rey (The King’s Fountain) painting in the Alfama District, ca. 1560-1580, Lisbon. Only three Africans were admitted into the order during the 16th century, two of whom were ambassadors of the kings of Kongo and Ndongo.

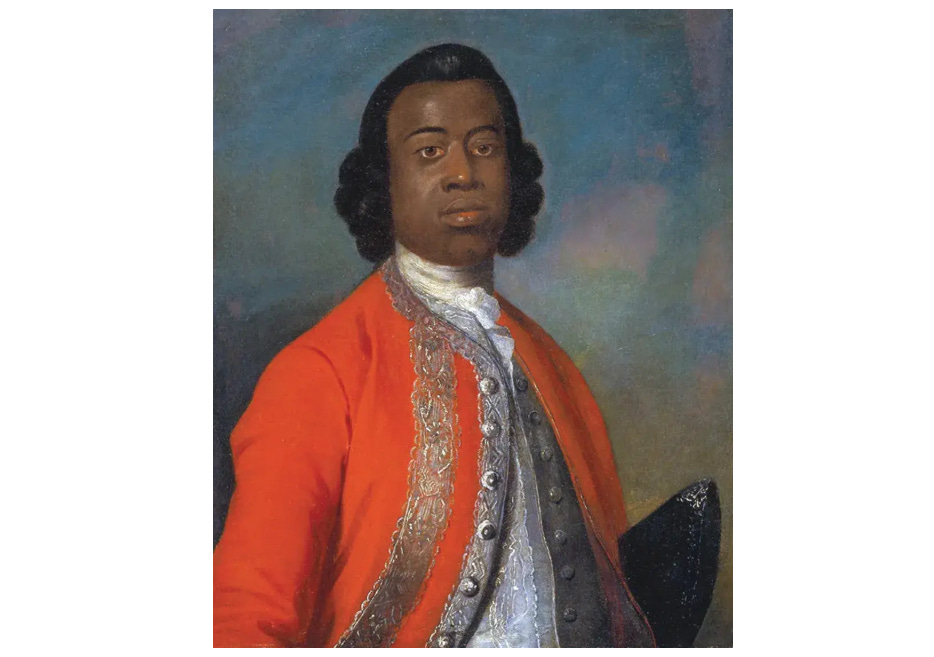

Portrait of William Ansah Sessarakoo, son of Eno Baisie Kurentsi (king John Currantee) of Anomabu, 1749. painting by Gabriel Mathias (1719–1804). The king of Annamaboe (Ghana) sent a two-pronged mission to France and England in the 1740s. The first mission was headed by William Ansa’s brother, named Louis Bassi, who successfully visited Paris, lived there for a few years under the care of King Louis XV, and returned. William Ansah, on the other hand, spent some months enslaved in Barbados in 1747-8 after the ship captain who was meant to take him to England died en route, and the prince was mistaken for a captive. He was promptly freed at the request of his father and was back on his mission to London by 1749, where this portrait was made.

It wasn't until the 17th century that Africans who travelled to Western Europe began extensively documenting their own accounts, creating a rich textual record that includes some of the first autobiographies published by African writers.

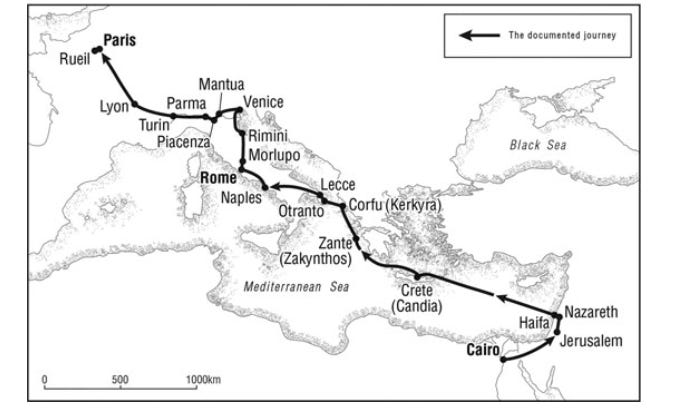

Among the earliest of these African autobiographies was the account of Sägga Kr ̣ әstos (Zaga Christ), an Ethiopian who claimed to be the son of emperor Yaʿǝqob (1597–1603, 1605–07), but was forced into exile via Egypt and Italy. Between July 1634 and April 1635, he was generously hosted by the Italian dukes of Mantua, Parma, Piacenza, and Turin.

In May 1635, he crossed the Alps and found his way to Paris, where he’d secure a generous royal pension and petition the French monarchy for support to return to Ethiopia. He authored a lengthy autobiographical work describing Gondarine Ethiopia, and an itinerary of his own journey to Rome, which he published in Paris and dedicated to Anne of Austria, Queen of France. He died in the residence of a Parisian cardinal in 1638.7

Portrait of Zaga Christ by Giovanna Garzoni, 1635. Allen Memorial Art Museum.

Sägga Krәstos’s journey. Map by Matteo Salvadore

In England, the earliest known autobiographies by West African writers date back to the 18th century. Most of their authors had been enslaved in their youth (such as Ukawsaw Gronniosaw from Bornu and Olaudah Equiano from Benin), or were young royals who had been sent for a Christian Education (eg, Philip Quaque from Ghana).8

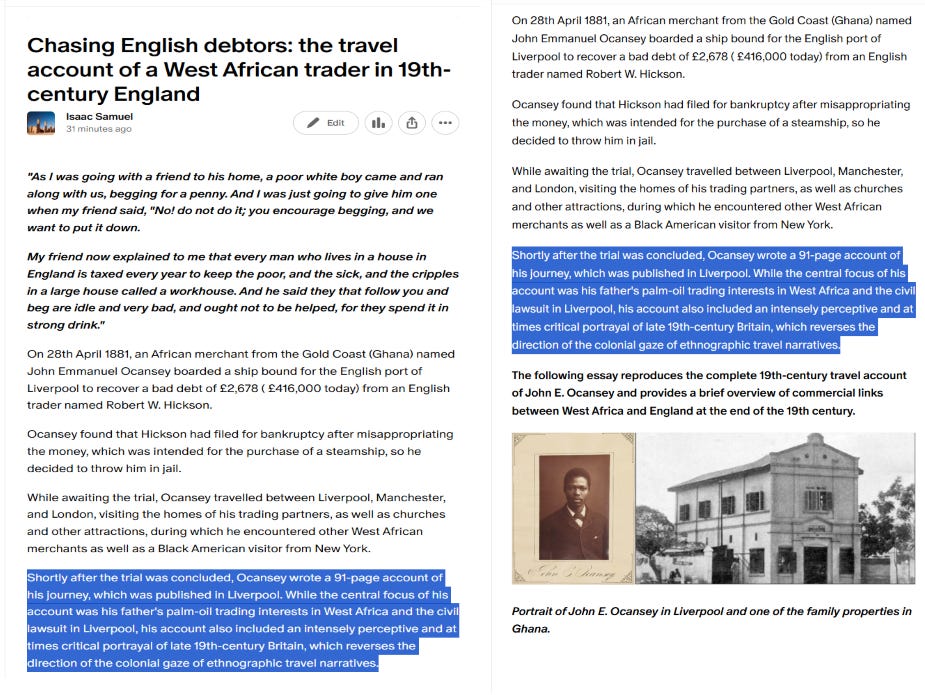

Autobiographies by West Africans who visited England on their own accord come from the 19th century, the most detailed of which belongs to the Gold Coast merchant John E. Ocansey, who went to Liverpool in 1881 to collect a bad debt of £2,678 ( about £416,000 today) from an English trader.

Ocansey found that trader, Robert W. Hickson, had filed for bankruptcy after misappropriating the money which was intended for the purchase of a steamship, so he decided to throw him in jail.

While awaiting the trial, Ocansey travelled between Liverpool, Manchester, and London, visiting the homes of his trading partners, as well as factories, markets, churches, and other attractions, where he encountered other West African merchants as well as a Black American visitor from New York.

Ocansey's 91-page account of his journey from Ghana to Liverpool is an intensely perceptive and at times critical portrayal of late 19th-century Britain, which reverses the direction of the colonial gaze of ethnographic travel narratives.

My latest Patreon article reproduces the full autobiographical work of John E. Ocansey and explores the commercial links between the Gold Coast and England in the late 19th century.

Please subscribe to read about it here, and support this newsletter:

Ancient genomes reveal cosmopolitan ancestry and maternal kinship patterns at post-Roman Worth Matravers, Dorset. By M. George B. Foody et al. West African ancestry in seventh-century England: two individuals from Kent and Dorset by Duncan Sayer et al., *see the supplementary materials of Foody et al.

West African ancestry in seventh-century England : two individuals from Kent and Dorset by Duncan Sayer et al.

See the section: ‘Out of Africa: historical and archaeological contexts’ In West African ancestry in seventh-century England: two individuals from Kent and Dorset by Duncan Sayer et al

A note towards quantifying the medieval Nubian diaspora by Adam Simmons, pg 27 In Dotawo: A Journal of Nubian Studies, 6. Soldiers of Christ: Saints and Saints' Lives from Late Antiquity and the Early Middle Ages By Thomas F. X. Noble, Thomas Head, pg 158

Black Africans in Renaissance Europe edited by T. F. Earle, K. J. P. Lowe. Black Lives in the English Archives, 1500-1677: Imprints of the Invisible By Imtiaz H. Habib. Africans in East Anglia, 1467-1833 By Richard Maguire. Visible Lives: Black Gondoliers and Other Black Africans in Renaissance Venice Kate Lowe

Black Lives in the English Archives, 1500-1677: Imprints of the Invisible by Imtiaz H. Habib, pg 268-269

The narrative of Zaga Christ (Sägga Kr ̣ әstos): the first published African autobiography (1635) by Matteo Salvadore

Black Writers in Britain, 1760-1890 by Paul Edwards, David Dabydeen, A History of Black and Asian Writing in Britain By C. L. Innes

Great insights. Africa was never cut from Europe, the Middle East, India and China. This idea always was quite Eurocentric.

There was a fashion in the 1700s for military bands in Europe to include African musicians, usually playing the large timpani drums or the "Jingling Johnny" reputedly borrowed from the Ottoman Turks. Often they were clothed in 'exotic' turban, blossoming pantallons, etc. inspired supposedly by the Turks, again. However, while a handful of individual stories survive their origins are unclear.