Kingdoms at the forest's edge: a history of Mangbetu (ca. 1750-1895)

The northern region of central Africa between the modern countries of D.R.Congo and South Sudan has a long and complex history shaped by its internal cultural developments and its unique ecology between the savannah and the forest.

Among the most remarkable states that emerged in this region was the kingdom of Mangbetu, whose distinctive architectural and art traditions captured the imagination of many visitors to the region, and continue to influence our modern perceptions of the region's societies and cultures.

This article explores the history of the Mangbetu kingdom and its cultural development from the 18th to the early 20th century.

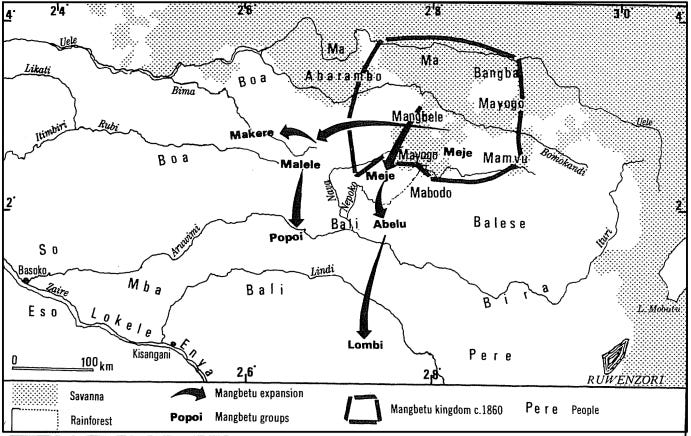

Map of D.R. Congo showing the Mangbetu homeland1.

Support AfricanHistoryExtra by becoming a member of our Patreon community, and keep this newsletter free for all:

The early history of Mangbetu: social complexity in the Uele river basin

The heartland of the Mangbetu kingdom is dominated by the Uele and Nepoko rivers, which cut across the northern region of the D.R.Congo. In this intermediate region between the savannah and the rainforest, diverse communities of farmers belonging to three of Africa's main language families settled and forged a new cultural tradition that coalesced into several polities.2

Linguistic evidence indicates that the region was gradually populated by heterogeneous groups of iron-age societies whose populations belonged to the language families of Ubangi, western Bantu, and southern-central Sudanic. Each of these groups came to be acculturated by their neighbors, developing decentralized yet large-scale social economies and institutions that differed from their neighbors in the Great Lakes region and west-central Africa.3

Among the groups associated with speakers of the southern-central Sudanic languages were the Mangbetu. The population drift of their ancestral groups southwards of the upper Uele basin began in the early 2nd millennium, and their communities were significantly influenced by their western Bantu-speaking neighbors such as the Mabodo and Buan. By the middle of the 18th century, incipient state institutions and military systems had developed among the Mangbetu and their neighbors as organizations structured around lineages became chiefdoms and kingdoms.4

map showing the expansion of Mangbetu-speaking groups.5

The Mangbetu Kingdom under King Nabiembali (r. 1800-1859) and King Tuba (r. 1859-1867)

Traditions and later written accounts associate the founding of the early Mangbetu polity with King Manziga, who is credited with overrunning several small polities along the Nepoko River during the late 18th century. His son and successor Nabiembali, undertook further conquests after 1800, expanding the kingdom northwards until the Uele River where he defeated the rival kingdom of Azande. Nabiembali's campaigns also extended east and west of the Magbentu heartlands, incorporating people from many different ethnic and linguistic backgrounds into the new state.6

However, Nabiembali's rapidly expanded kingdom retained many of its early institutions of the pre-existing lineage groups. Royal ideology and legitimacy were highly personalized and were largely dependent on the success of the individual ruler in balancing military force with diplomacy rather than making dynastic claims or divine right. Political relationships continued to be defined in terms of kinship with the ruler's lineage (known as the ‘mabiti’) as well as his clients, forming the core of the court, and alliances were maintained through intermarriages between the leaders of subject groups.7

The core of Nabiembali's military was the royal bodyguard comprising professional mercenaries, kinsmen, and dependents of the king, and it was sustained by revenues from the produce of its immediate clients and dependents. Lacking a centralized political system to maintain the loyalty of his newly conquered subjects, Nabiembali was overthrown by his sons in 1859, who established semi-independent Mangbetu kingdoms, the most powerful of which was led by Tuba who controlled the core regions of the kingdom.8

As king of the Mangbetu heartland, Tuba was forced to fight the rebellious princes around him, who were inturn compelled to forge alliances with the neighboring Azande kingdom. A series of battles between Tuba and his rivals —who included Nabiembali's military commander Dakpala— culminated with his death in 1867, and he was succeeded by his son Mbunza. The latter was able to hold off his rivals, succeeded in defeating and killing Dakpala, and briefly forged commercial ties with ivory traders from the Sudanese Nile valley.9

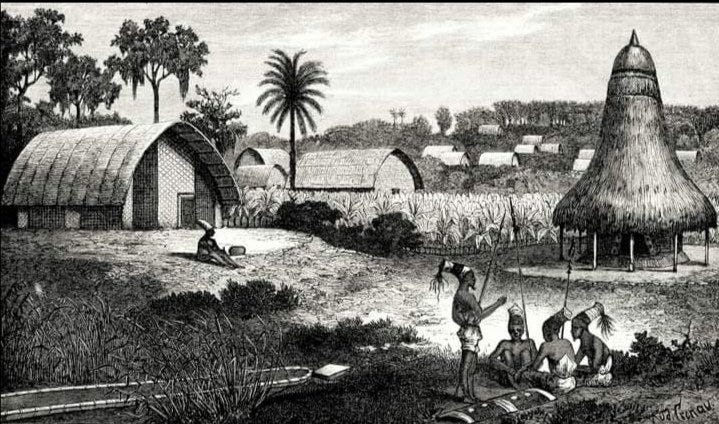

Mangebtu settlement at Nangazizi, ca. 1870, illustration by Schweinfurth

Mangbetu kingdom under King Mbunza (r. 1867-1873): external contacts and descriptions of Mangbetu society.

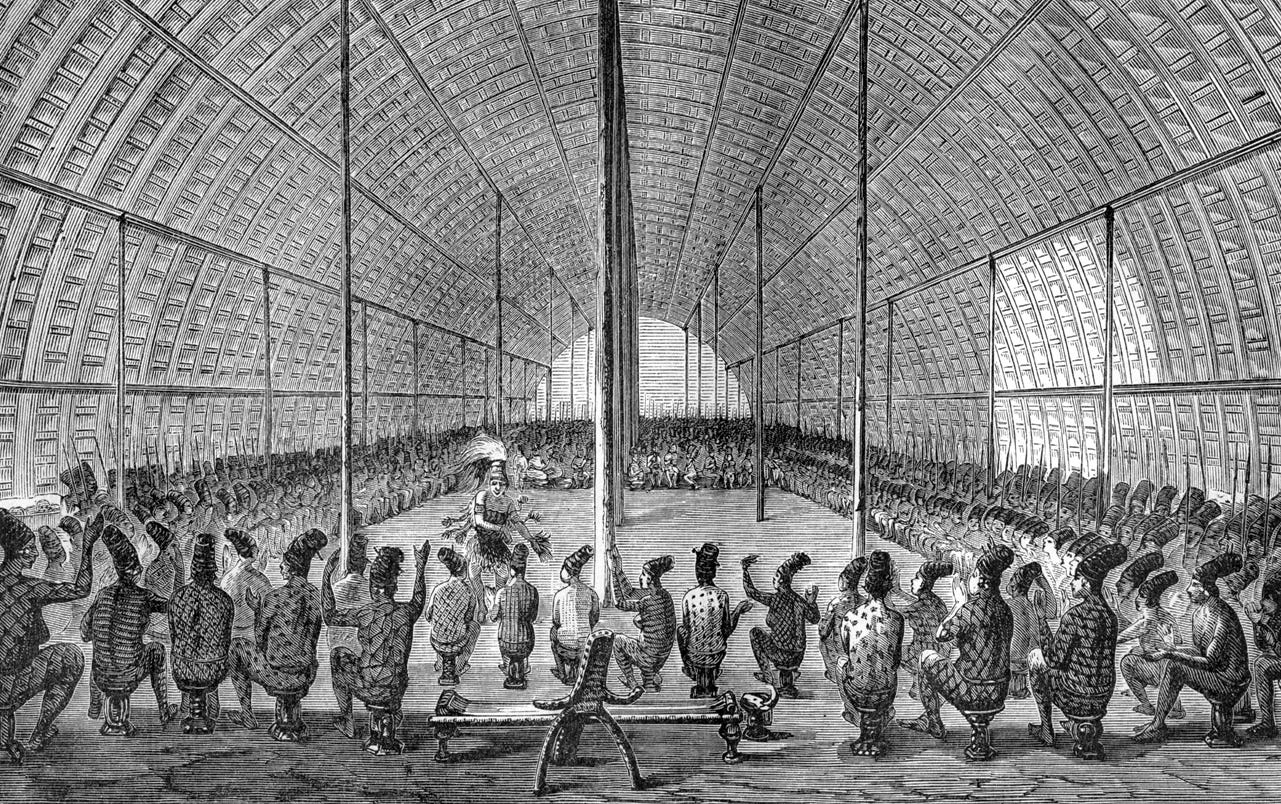

King Mbunza established his capital at Nangazizi, where he resided in a large palace built entirely out of wood, an architectural tradition common in the region, whose royal/public halls rivaled some of the world's largest wooden structures10. In 1870, the Swiss traveler Georg Schweinfurth was briefly hosted in Mbunza's palace, whose grandeur and elegance captured the visitor's imagination. Schweinfurth's description of the Mangbetu politics, culture, and artworks would inform the writings of most of his successors.11

The capital was bisected by a broad central plaza surrounded by the houses of the queens and courtiers, two large public halls, with the bigger one measuring 150ftx50ft and 50 feet high, and a large royal enclosure where the king had storehouses of ivory and weapons. The arches of the public halls' vaulted roofs were supported by five and three "long rows of pillars formed from perfectly straight tree-stems," its rafters and roofing were made from leafstalks of the palm-tree, its floor was plastered with red clay "as smooth as asphalt," and its sides were "enclosed by a low breastwork" that allowed light to enter the building.12

King Munza and the Mangbetu queens in the public hall, ca. 1870, illustration by Schweinfurth

exterior of a large Mangbetu hall, ca. 1909, AMNH. this is a later structure built by the Mangbetu king Okondo (r.1902-1915), it has a gable roof instead of the arched roof of Mbunza’s hall but is otherwise structurally similar to the latter.

The kingdom's craft industries were highly productive, and its artists were renowned for their sophisticated forging technology, particularly the making of ornaments and weapons in copper, iron, ivory, and wood. The manufacture of the weapons in particular was described glowingly by Schweinfurth, especially the scimitars (carved blades) of various types, as well as daggers, knives, and steel chains, which he calls "masterpieces" and claims that Mangbetu's smiths "surpass even the Mohammedans of Northern Africa." and rivals "the productions of our European craftsmen."13

The Mangbetu king and his courtiers developed symbols of royal insignia14, including ornaments made of copper and ivory, as well as ceremonial weapons and vessels15, musical instruments (trumpets, bells, timbrels, gongs, kettle-drums, and five-stringed 'mandolins'/harps16). These items, which are mentioned in several 19th century accounts and appear in many museums today, were part of the primary figurative tradition of the various societies of the Uele basin and were not confined to the royalty nor even to the Mangbetu.17

Schweinfurth regarded Mbunza as a powerful absolute monarch, whose statecraft was influenced by the Lunda empire to the south. He claims that the king ruled by divine kingship, commanded hundreds of courtiers and subordinate governors, required regular tribute, and imposed commercial monopolies on long-distance trade in ivory and copper.18

Historians regard most of Schweinfurth's interpretations and descriptions of Mangbetu politics and kingship as embellished, being influenced as much by his preconceptions and personal motivations as by the observations he was able to make during his very brief 13-day stay at the capital where he hardly had any interpreters. However, with the exception of the usual myths and stereotypes about central Africa found in European travelogues of the time19, most of his accounts and illustrations of Mangbetu society were relatively accurate and conformed to similar descriptions from later traveler accounts and in traditional histories documented in the early 20th century.20

Side-blown Trumpets from Mangbetu, 19th-20th century, Met museum, AMNH. the anthropomorphic figures with long heads adorned with elaborative hairstyles reflect Mangbetu cultural practices of the Mabiti royal lineage.

Figurative Harps from Mangbetu, 19th-20th century, Met Museum, AMNH.

brass and iron swords from Mangbetu, 19th-20th century, AMNH, British Museum.

Mangbetu under King Yangala (r. 1873-1895): decline and fall.

King Mbunza's rivals and their Azande allies continued to pose a threat in the northern frontier of the kingdom. By the early 1870s, these rivals —who included Dakpala's son; Yangala— allied with the Azande and a group of Nile traders whom Mbunza had expelled to form a coalition that defeated Mbunza in 1873. Yangala was installed as the king at Nangazizi but retained all of his predecessor's institutions in order to portray himself as a legitimate heir. He also married Mbunza's sister Nenzima, who acted as the 'prime minister' during his reign and his successor’s reigns.21

Yangala largely succeeded in protecting Mangbetu from the brief but intense period of turmoil in which the societies of the Uele basin were embroiled in the expansionism of the Khedivate of Egypt and the Nile traders. Yangala's kingdom was now only one of several Mangbetu states, some of which were ruled by Mbunza's kinsmen like Mangbanga and Azanga who were equally successful in fending off external threats. All hosted later visitors like Wilhelm Junker and Gaetano Casiti who were also received in the large public hall described by Schweinfurth, and were equally enamored with Mangbetu art.22

After the collapse of the Khedivate in Sudan, the Mangbetu king Yangala would only enjoy a decade of respite before a large military column of King Leopold's Congo State arrived at his capital in 1892. The internecine rivalries between the Mangbetu rulers and lineages compelled Yangala to submit to the Belgians inorder to retain some limited authority. But after his death in 1895, his successors such as king Mambanga (r. 1895-1902) and Okondo (r. 1902-1915) were chosen by the Belgians who transformed the role of the rulers in relation to their subjects and effectively ended the kingdom’s autonomy.23

Around 1910, Mangentu’s artists produced more than 4,000 artworks which were among the 49 tons of cultural material collected by the American Museum of Natural History in northern D.R. Congo, whose curators had been drawn to Mangebtu’s art tradition, thanks to the artworks collected during the 19th century. These artworks and the evolution of their interpretation continue to influence how the history of Mangbetu and the northern D.R.C is reconstructed.24

carved ivory spoons and forks, Okondo’s residence, Mangbetu, Congo, ca. 1913, AMNH.

The history of central African societies and kingdoms has been profoundly influenced by the evolution of social divisions such as the Tutsi and Hutu. Read about the dynamic history of this Tutsi / Hutu dichotomy in the kingdoms of Rwanda and Nkore here:

map by the ‘joshua project’

Paths in the Rainforests: Toward a History of Political Tradition in Equatorial Africa by Jan M. Vansina pg 169)

Paths in the Rainforests: Toward a History of Political Tradition in Equatorial Africa by Jan M. Vansina pg 5-6, 171-172)

Paths in the Rainforests: Toward a History of Political Tradition in Equatorial Africa by Jan M. Vansina pg 173-175, UNESCO history of Africa vol 5 pg 520-523)

Map by Jan M. Vansina

Paths in the Rainforests: Toward a History of Political Tradition in Equatorial Africa by Jan M. Vansina pg 176, Ten Years in Equatoria and the Return with Emin Pasha, Volume 1 By Gaetano Casati pg 115-117)

Paths in the Rainforests: Toward a History of Political Tradition in Equatorial Africa by Jan M. Vansina pg 176-177, Long-Distance Trade and the Mangbetu by Curtis A. Keim pg 5)

Long-Distance Trade and the Mangbetu by Curtis A. Keim pg 5)

Long-Distance Trade and the Mangbetu by Curtis A. Keim pg 6-8)

Precolonial African Material Culture. By V. Tarikhu Farrar, pg 219-222., junker’s account also mentions ‘assembly halls’ among the Zande as well; Travels in Africa during the years 1875[-1886] by Junker, Wilhelm, Vol. 3, pg 7, 18, 26, 47, 88.

The Scramble for Art in Central Africa edited by Enid Schildkrout, pg 137-147)

The Heart of Africa: Three Years' Travels and Adventures in the Unexplored Regions of Central Africa from 1868 to 1871, Volume 2 by Georg August Schweinfurth pg 37-43, 65, 76-77, 97-99)

The Scramble for Art in Central Africa edited by Enid Schildkrout, pg 111-112, The Heart of Africa by Georg August Schweinfurth pg 107-110)

Unpacking Culture: Art and Commodity in Colonial and Postcolonial Worlds edited by Ruth B. Phillips, Christopher B. Steiner pg 197, 202-203.

The Heart of Africa by Georg August Schweinfurth pg 41, 75, 117)

Ten Years in Equatoria and the Return with Emin Pasha, Volume 1 By Gaetano Casati pg pg 188, 194-195, 244

The Scramble for Art in Central Africa edited by Enid Schildkrout pg 109-111, 121-124, Unpacking Culture: Art and Commodity in Colonial and Postcolonial Worlds edited by Ruth B. Phillips, Christopher B. Steiner pg 200-203

The Heart of Africa by Georg August Schweinfurth pg 95-96, 99)

The historian Curtis keim calls the discursive tradition pioneered by Schweinfurth the "Mangbetu myth"; which consists of a set of stereotypical elements such as the nobility of the royals and the splendor of courtly life that is then juxtaposed with erroneous references to their 'savagery' and 'cannibalism'. The latter of which ironically was an accusation the Mangbetu also leveled against Schweinfurth who was, after all, accumulating a vast collection of human skulls from across the world for his pseudoscientific studies of eugenics, and thus compelled the Mangbetu to sell him human skulls, something the Africans found bizarre, and insisted was proof of Schweinfurth's insatiable cannibalism, an accusation he ironically dismissed as stupid. see: The Scramble for Art in Central Africa edited by Enid Schildkrout, Curtis A. Keim pg 137, The Heart of Africa by Georg August Schweinfurth pg 54-55, Mistaking Africa: Misconceptions and Inventions By Curtis Keim pg 107-111.

Long-Distance Trade and the Mangbetu by Curtis A. Keim pg 2-3, The Scramble for Art in Central Africa edited by Enid Schildkrout, pg 136-138)

Long-Distance Trade and the Mangbetu by Curtis A. Keim pg 9-10, 12, Ten Years in Equatoria and the Return with Emin Pasha, Volume 1 By Gaetano Casati pg 118, 146-147 The Scramble for Art in Central Africa edited by Enid Schildkrout pg 125)

Long-Distance Trade and the Mangbetu by Curtis A. Keim pg 12-13, 17-21, Ten Years in Equatoria and the Return with Emin Pasha, Volume 1 By Gaetano Casati pg 82, The Scramble for Art in Central Africa edited by Enid Schildkrout pg 116

(an aspect of the Mangebtu response to the Belgian atrocities can be glimpsed in the satirical figure of a saluting Belgian soldier on the third harp -shown above- who is naked all but his cap) see:

Methodology, Ideology and Pedagogy of African Art: Primitive to Metamodern edited by Moyo Okediji pg 83-85, Mangbetu Tales of Leopard and Azapane: Trickster as Resistance Hero by Robert Mckee

The Scramble for Art in Central Africa edited by Enid Schildkrout pg 119, 125, Unpacking Culture: Art and Commodity in Colonial and Postcolonial Worlds edited by Ruth B. Phillips, Christopher B. Steiner pg 199-204.

The architecture presented above in the first pic is really new to me, what were they made of, thanks for the new wonderful surprises.