Life and works of Africa's most famous Woman scholar: Nana Asmau (1793-1864)

On the contribution of Muslim women in African history.

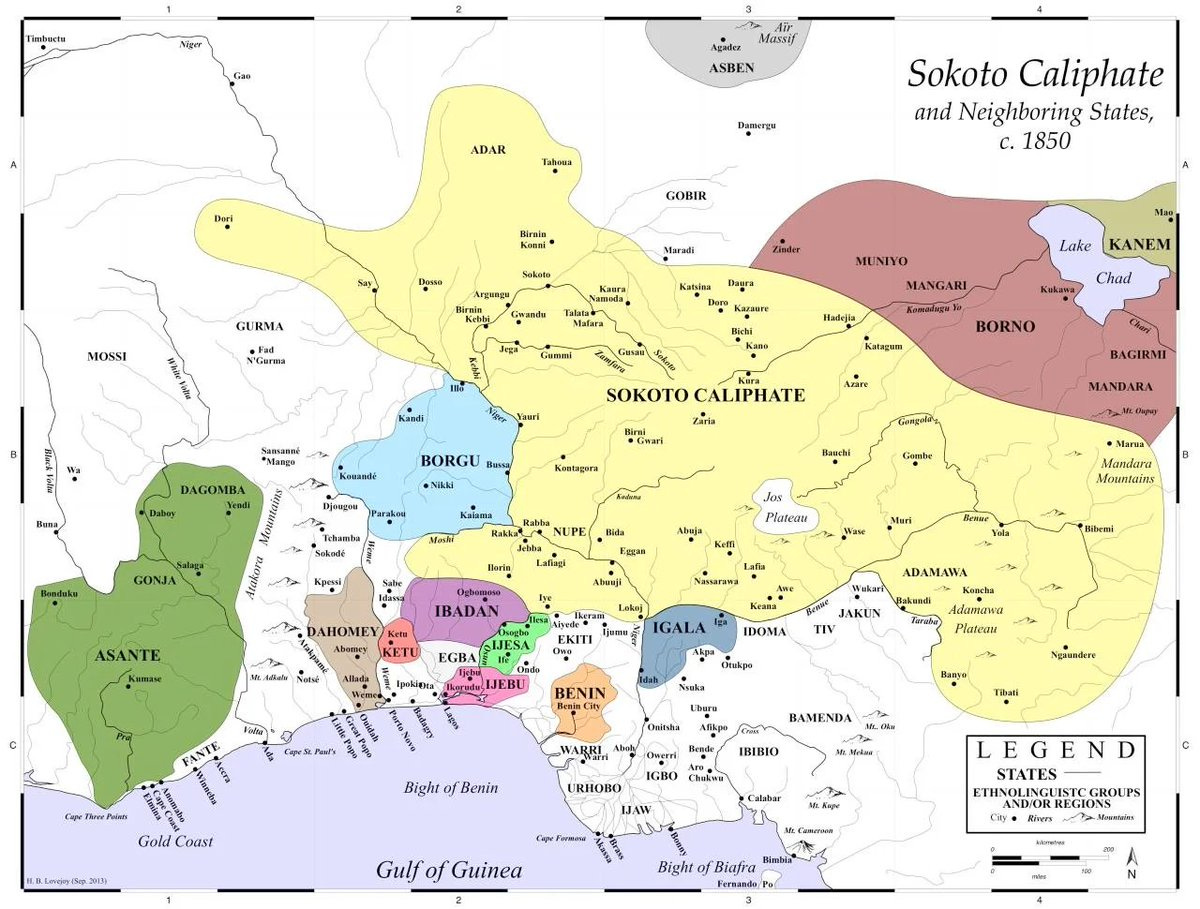

Throughout its history, Africa has produced many notable women scholars who contributed greatly to its intellectual heritage.1 But few are as prominent as the 19th-century scholar Nana Asmau from the Sokoto empire in what is today northern Nigeria.

Nana Asmau was one of Africa's most prolific writers, with over eighty extant works to her name and many still being discovered. She was a popular teacher, a multilingual author, and an eloquent ideologue, able to speak informedly on a wide range of topics including religion, medicine, politics, history, and issues of social concern. Her legacy as a community leader for the women of Sokoto survives in the institutions created out of her social activism, and the voluminous works of poetry still circulated by students.

This article explores the life and works of Nana Asmau, highlighting some of her most important written works in the context of the political and social history of west Africa.

Map of the Sokoto Caliphate in 1850, by Paul Lovejoy

Support AfricanHistoryExtra by becoming a member of our Patreon community, and keep this newsletter free for all:

Early life of Nana Asmau and the foundation of the Sokoto state.

Born Nana Asma'u bint Usman 'dan Fodio in 1793 into a family of scholars in the town of Degel within the Hausa city-state of Gobir, she composed the first of her approximately eighty known works in 1820. Many of these works have been translated and studied in the recent publications of Jean Boyd and other historians. The fact that Nana Asmau needed no male pseudonym, unlike most of her Western peers, says a lot about the intellectual and social milieu in which she operated.

While Asmau was extraordinary in her prolific poetic output and activism, she was not an exception but was instead one in a long line of women scholars that came before and continued after her. Asmau was typical of her time and place with regard to the degree to which women pursued knowledge, and could trace eight generations of female scholars both before and after her lifetime. At least twenty of these women scholars can be identified from her family alone between the 18th and 19th centuries based on works written during this period, seven of whom were mentioned in Asmau’s compilation of women scholars, and at least four of whose works survive.2

These women were often related to men who were also accomplished scholars, the most prominent of whom was Asmau's father Uthman dan Fodio who founded the Sokoto state. One of the major preoccupations of Uthman and his successors was the abolition of "innovation" and a return to Islamic "orthodoxy". Among the main criticisms that he leveled against the established rulers (and his own community) was their marginalization of women in Education. Disregarding centuries of hadiths and scholarly commentaries on the message of the Prophet, the shaykh emphasized the need to recognize the fact that Islam, in its pristine form, didn’t tolerate for any minimalization of women’s civic rights.3

He writes that “Most of our educated men leave their wives, their daughters and their female relatives ... to vegetate, like beasts, without teaching them what Allah prescribes they should be taught and without instructing them in the articles of Law that concern them. This is a loathsome crime. How can they allow their wives, daughters, and female dependents to remain prisoners of ignorance, while they share their knowledge with students every day? In truth, they are acting out of self-interest”.4

He adds; “One of the root causes of the misfortunes of this country is the attitude taken by Malams who neglect the welfare of the women. they [Women] are not taught what they ought to know about trading transactions; this is quite wrong and a forbidden innovation. It is obligatory to teach wives, daughters, and female dependants: the teaching of [male] pupils is optional and what is obligatory has priority over what is optional.”5 And in another text critical of some of the 'pagan' practices he saw among some of his own community, he writes that "They do not teach their wives nor do they allow them to be educated, All these things stem from ignorance. They are not the Way of the Prophet".6

Asmau’s creative talents were cultivated in the school system of Islamic West Africa, in which learning was individualized under a specific teacher for an individual subject, relying on reference material from their vast personal libraries. Asmau was taught by multiple teachers throughout her life even as she taught other students, and was especially fortunate as her own family included highly accomplished scholars who were teachers in Degel. These teachers included her sister, Khadija, her father, Shaykh Uthman, and her half-brother, Muhammad Bello, all of whom wrote several hundred works combined, many of which survived to the present day.7

Nana Asma'u mastered the key Islamic sciences, acquired fluency in writing the languages of Hausa, Arabic, and Tamasheq, in addition to her native language Fulfulde, and became well-versed in legal matters, fiqh (which regulates religious conduct), and tawhid(dogma). Following in the footsteps of her father, she became deeply immersed in the dominant Qadriyya order of Sufi mysticism. The first ten years of her life were devoted to scholarly study, before the beginning of Uthman’s movement to establish the Sokoto state. There followed a decade of itinerancy and warfare, through which Asma’u continued her studies, married, and wrote poetic works.8

Around 1807, Asmau married Gidado dan Laima (1776-1850 ), a friend of Muhammad Bello who later served as wazir (‘prime minister’) of Sokoto during the latter's reign. Gidado encouraged Asmau’s intellectual endeavors and, as Bello’s closest companion, was able to foster the convergence of his wife’s interests with her brother’s. In Asmaus elegy for Gidado titled; Sonnore Gid'ad'o (1848), she lists his personal qualities and duties to the state, mentioning that he "protected the rights of everyone regardless of their rank or status… stopped corruption and wrongdoing in the city and … honoured the Shehu's womenfolk."9

Asmau’s role in documenting the history and personalities of Sokoto

Asmau was a major historian of Sokoto, and an important witness of many of the accounts she described, some of which she may have participated in as she is known to have ridden her horse publically while traveling between the cities of Sokoto, Kano, and Wurno10.

Asmau wrote many historical works about the early years of Uthman Fodio's movement and battles, the various campaigns of Muhammad Bello (r. 1817-1837) eg his defeat of the Tuaregs at Gawakuke in 1836, and the campaigns of Aliyu (r. 1842-1859) eg his defeat of the combined forces of Gobir and Kebbi. She also wrote about the reign and character of Muhammad Bello, and composed various elegies for many of her peers, including at least four women scholars; Fadima (d. 1838), Halima (d. 1844), Zaharatu (d. 1857), Fadima (d. 1863) and Hawa’u (1858) —the last of whom was one of her appointed women leaders11. All of these were of significant historical value for reconstructing not just the political and military history of Sokoto, but also its society, especially on the role of women in shaping its religious and social institutions12.

folio from the fulfulde manuscript Fa'inna ma'al Asur Yasuran (So Verily), 1822, SOAS

One notable battle described by Asmau was the fall of the Gobir capital Alƙalawa in 1808, which was arguably the most decisive event in the foundation of Sokoto. Folklore attributes to Asmau a leading role in the taking of the capital. She is said to have thrown a burning brand to Bello who used the torch to set fire to the capital, and this became the most famous story about her. However, this wasn’t included in her own account, and the only likely mention of her participation in the early wars comes from the Battle of Alwasa in 1805 when the armies of Uthman defeated the forces of the Tuareg chief Chief of Adar, Tambari Agunbulu, "And the women added to it by stoning [enemies] - and leaving them exposed to the sun."13

After the first campaigns, the newly established state still faced major threats, not just from the deposed rulers who had fled north but also from the latter's Tuareg allies. One of the first works written by Asmau was an acrostic poem titled, Fa'inna ma'a al-'usrin yusra (1822), which she composed in response to a similar poem written by Bello who was faced with an invasion by the combined forces of the Tuareg Chief Ibrahim of Adar, and the Gobir sultan Ali. 14

This work was the first in the literary collaboration between Asma'u and Muhammad Bello, highlighting their equal status as intellectual peers. The Scottish traveler Hugh Clapperton, who visited Sokoto in 1827, noted that women were “allowed more liberty than the generality of Muslim women”15. The above observation doubtlessly reveals itself in the collaborative work of Asmau and Bello titled; Kitab al-Nasihah (book of women) written in 1835 and translated to Fulfulde and Hausa by Asmau 1836. It lists thirty seven sufi women from across the Muslim world until the 13th century, as well as seven from Sokoto who were eminent scholars.16

Asmau provided brief descriptions of the Sokoto women she listed, who included; Joda Kowuuri, "a Qur'anic scholar who used her scholarship everywhere," Habiba, the most revered "teacher of women," Yahinde Limam, who was "diligent at solving disputes", and others including Inna Garka, Aisha, lyya Garka and Aminatu bint Ade, in addition to "as many as a hundred" who she did not list for the sake of brevity.17 The poem on Sufi Women emphasizes that pious women are to be seen in the mainstream of Islam, and could be memorized by teachers for instructional purposes.18

folios from the ‘kitab al-nasiha’ (Book of Women), 1835/6, SOAS Library

Asmau’s role in women’s education and social activism.

The above work on sufi women wasn’t intended to be read as a mere work of literature, but as a mnemonic device, a formula to help her students remember these important names. It was meant to be interpreted by a teacher (jaji) who would have received her instructions from Asmau directly. Asmau devoted herself to extensive work with the teachers, as it was their job to learn from Asma'u what was necessary to teach to other teachers of women, whose work involved the interpretations of very difficult and lengthy material about Islamic theology and practices.19

Asma'u was particularly distinguished as the mentor and tutor of a community of jajis through whom the key tenets of Sufi teachings about spirituality, ethics, and morality in the handling of social responsibilities spread across all sections of the society.20 The importance of providing the appropriate Islamic education for both elite and non-elite women and girls was reinforced by the growing popularity non-Islamic Bori religion, which competed for their allegiance.21 One of Asmau’s writings addressed to her coreligionists who were appealing to Bori diviners during a period of drought, reveals the extent of this ideological competition.22

Groups of women, who became known as the ‘Yan Taru (the Associates) began to visit Asma’u under the leadership of representatives appointed by her. The Yan Taru became the most important instrument for the social mobilization, these "bands of women students" were given a large malfa hat that's usually worn by men and the Inna (chief of women in Gobir) who led the bori religion in Gobir. By giving each jaji such a hat, Asmau transformed it into an emblem of Islamic learning, and a symbol of the wearer’s authority.23

Asmau’s aim in creating the ‘Yan Taru was to educate and socialize women. Asmau's writings also encouraged women's free movement in public, and were addressed to both her students and their male relatives, writing that: "In Islam, it is a religious duty to seek knowledge Women may leave their homes freely for this."24 The education network of the ‘Yan Taru was already widespread as early as the 1840s, as evidenced in some of her writings such as the elegy for one of her students, Hauwa which read;

"[I] remember Hauwa who loved me, a fact well known to everybody. During the hot season, the rains, harvest time, when the harmattan blows, And the beginning of the rains, she was on the road bringing people to me… The women students and their children are well known for their good works and peaceful behaviour in the community."25

Many of Asmau's writings appear to have been intended for her students26, with many being written in Fulfulde and Hausa specifically for the majority of Sokoto’s population that was unfamiliar with Arabic. These include her trilingual work titled ‘Sunago’, which was a nmemonic device used for teaching beginners the names of the suras of the Qur'an.27 Other works such as the Tabshir al-Ikhwan (1839) was meant to be read and acted upon by the malarns who specialized in the ‘medicine of the prophet’28, while the Hausa poem Dalilin Samuwar Allah (1861) is another work intended for use as a teaching device.29

Asmau also wrote over eighteen elegies, at least six of which were about important women in Sokoto. Each is praised in remembrance of the positive contributions she made to the community, with emphasis on how her actions defined the depth of her character.

These elegies reveal the qualities that were valued among both elite and non-elite women in Sokoto. In the elegy for her sister Fadima (1838), Asmau writes; “Relatives and strangers alike, she showed no discrimination. she gave generously; she urged people to study. She produced provisions when an expedition was mounted, she had many responsibilities. She sorted conflicts, urged people to live peacefully, and forbade squabbling. She had studied a great deal and had deep understanding of what she had read.”30

Asma’u did not just confine her praise to women such as Fadima who performed prodigious tasks, but, also those who did more ordinary tasks. In her elegy for Zaharatu (d. 1857), Asmau writes: “She gave religious instruction to the ignorant and helped everyone in their daily affairs. Whenever called upon to help, she came, responding to layout the dead without hesitation. With the same willingness she attended women in childbirth. All kinds of good works were performed by Zaharatu. She was pious and most persevering: she delighted in giving and was patient and forbearing.”31

A list of her students in specific localities, which was likely written not long after her death, mentions nearly a hundred homes.32

Folio from the fulfulde manuscript ‘Sunago’ 1829, BNF Paris.

folios from the Hausa manuscript 'Qasidar na Rokon Allah', early 19th century, SOAS Library

Asmau’s role in the political and intellectual exchanges of West Africa.

After the death of Muhammad Bello, Asmau’s husband Gidado met with the senior councilors of Sokoto in his capacity as the wazir, and they elected Atiku to the office of Caliph. Gidado then relinquished the office of Wazir but stayed in the capital. Asmau and her husband then begun to write historical accounts of the lives of the Shehu and Bello for posterity, including the places they had lived in, their relatives and dependants, the judges they had appointed, the principal imams of the mosques, the scholars who had supported them, and the various offices they created.33

Besides writing extensively about the history of Sokoto's foundation, the reign of Bello, and 'text-books' for her students, Asmau was from time to time invited to advise some emirs and sultans on emergent matters of state and rules of conduct. One of her works titled 'Tabbat Hakiya' (1831), is a text about politics, informs people at all levels of government about their duties and responsibilities. She writes that;

"Rulers must persevere to improve affairs, Do you hear? And you who are ruled, do not stray: Do not be too anxious to get what you want. Those who oppress the people in the name of authority Will be crushed in their graves… Instruct your people to seek redress in the law, Whether you are a minor official or the Imam himself. Even if you are learned, do not stop them."34

Asmau, like many West African scholars who could voice their criticism of politicians, also authored critiques of corrupt leaders. An example of this was the regional governor called ɗan Yalli, who was dismissed from office for misconduct, and about whom she wrote;

"Thanks be to God who empowered us to overthrow ɗan Yalli. Who has caused so much trouble. He behaved unlawfully, he did wanton harm.. We can ourselves testify to the Robberies and extortion in the markets, on the Highways and at the city gateways".35

folios from the Fulfulde poem ‘Gikku Bello’ 1838/9. BNF Paris

As an established scholar, Asmau corresponded widely with her peers across West Africa. She had built up a reputation as an intellectual leader in Sokoto and was recognized as such by many of her peers such as the Sokoto scholar Sheikh Sa'ad who wrote this of her; "Greetings to you, O woman of excellence and fine traits! In every century there appears one who excels. The proof of her merit has become well known, east and west, near and far. She is marked by wisdom and kind deeds; her knowledge is like the wide sea."36

Asmau’s fame extended beyond Sokoto, for example, the scholar Ali Ibrahim from Masina (in modern Mali) wrote: "She [Asma’u] is famous for her erudition and saintliness which are as a bubbling spring to scholars. Her knowledge, patience, and sagacity she puts to good use as did her forebears" and she replied: "It would be fitting to reward you: you are worthy of recognition. Your work is not inferior and is similar in all respects to the poetry you mention."37

She also exchanged letters with a scholar from Chinguetti (Shinqit in Mauritania) named Alhaji Ahmad bin Muhammad al-Shinqiti, and welcomed him to Sokoto during his pilgrimage to Mecca, writing: "Honour to the erudite scholar who has left his home To journey to Medina. Our noble, handsome brother, the hem of whose scholarship others cannot hope to touch. He came bearing evidence of his learning, and the universality of his knowledge.38"

Asm’u died in 1864 at the age of 73, and was laid to rest next to the tomb of the Shehu. Her brother and students composed elegies for her, one of which read that

"At the end of the year 1280 Nana left us, Having received the call of the Lord of Truth.

When I went to the open space in front of Giɗaɗo’s house I found it too crowded to pass through Men were crying, everyone without exception Even animals uttered cries of grief they say.

Let us fling aside the useless deceptive world, We will not abide in it forever; we must die. The benevolent one, Nana was a peacemaker. She healed almost all hurt."39

After Nana Asma’u’s death, her student and sister Maryam Uwar Deji succeeded her as the leader of the ‘Yan Taru, and became an important figure in the politics of Kano, an emirate in Sokoto.40 Asmau’s students, followers, and descendants carried on her education work among the women of Sokoto which continued into the colonial and post-colonial era of northern Nigeria.

Folios from the Hausa poem titled ‘Begore’ and a poem in Fulfulde titled ‘Allah Jaalnam’.41

Conclusion: Asmau’s career and Muslim women in African history.

Nana Asmau was a highly versatile and polymathic writer who played a salient role in the history of West Africa. She actively shaped the political structures and intellectual communities across Sokoto and was accepted into positions of power in both the secular and religious contexts by many of her peers without attention to her gender.

The career of Asmau and her peers challenge Western preconceptions about Muslim women in Africa (such as those held by Hugh Clapperton and later colonialists) that presume them to be less active in society and more cloistered than non-Muslim women.42 The corpus of Asmau provides firsthand testimony to the active participation of women in Sokoto's society that wasn't dissimilar to the experiences of women in other African societies.

Asmau's life and works are yet another example of the complexity of African history, and how it was constantly reshaped by its agents --both men and women.

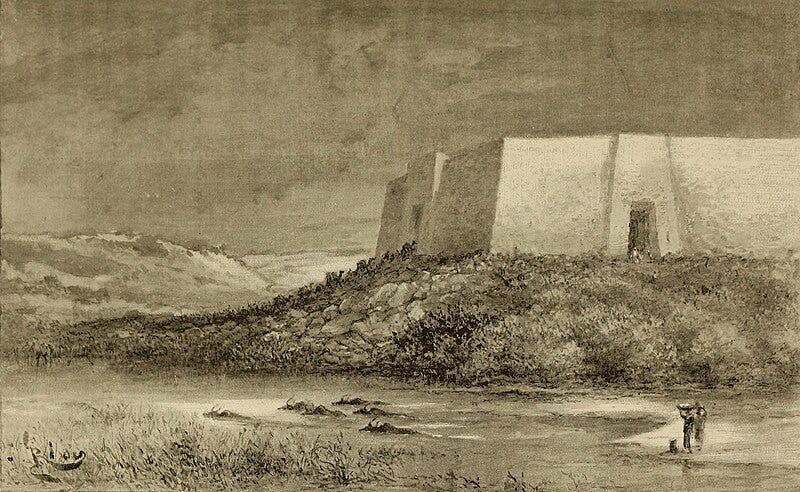

View of Sokoto from its outskirts., ca. 1890

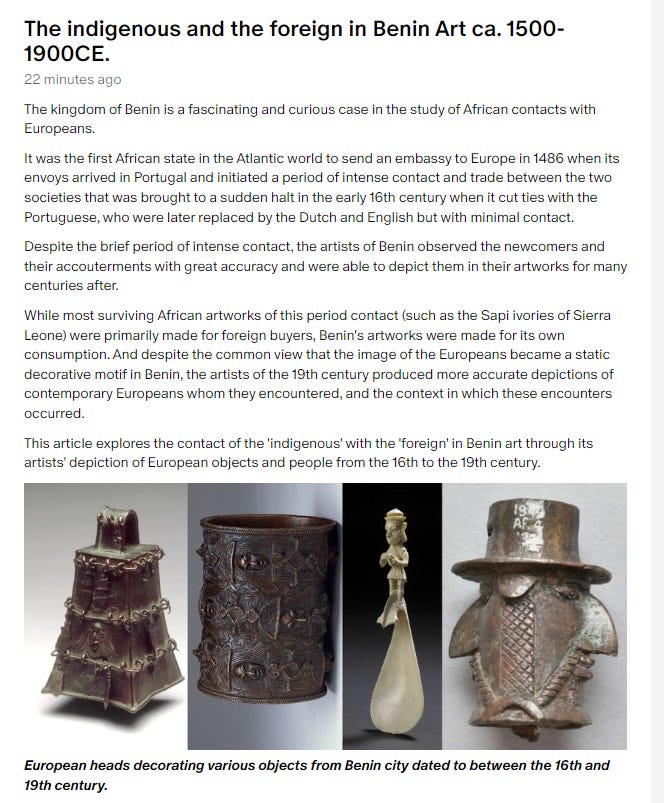

To the south of Sokoto was the old kingdom of Benin, which had for centuries been in close contact with European traders from the coast. These foreigners were carefully and accurately represented in Benin’s art across five centuries as their relationship with Benin evolved.

read more about the evolution of Europeans in Benin’s art here:

Women Writing Africa: a catalogue of women scholars across the African continent from antiquity until the 19th century

Women contributed greatly to Africa's intellectual history, but given the nascent nature of studies on the continent's intellectual past, the writings of African women scholars have often been overlooked and the translation and interpretation of the documents written by individual women scholars is scarce.

Educating Muslim Women: The West African Legacy of Nana Asma u 1793-1864 By Beverley Mack, Jean Boyd pg 174-179)

Feminist or Simply Feminine ? Reflection on the Works of Nana Asma'u by Chukwuma Azuonye pg 67, Educating Muslim Women: The West African Legacy of Nana Asma u 1793-1864 By Beverley Mack, Jean Boyd pg 29)

Educating Muslim Women: The West African Legacy of Nana Asma u 1793-1864 By Beverley Mack, Jean Boyd pg 29-30

The Fulani Women Poets by Jean Boyd pg 128)

Educating Muslim Women: The West African Legacy of Nana Asma u 1793-1864 By Beverley Mack, Jean Boyd pg 31)

Educating Muslim Women: The West African Legacy of Nana Asma u 1793-1864 By Beverley Mack, Jean Boyd pg 26-27)

One Woman's Jihad: Nana Asma'u, Scholar and Scribe By Beverly B. Mack, Jean Boyd pg 7-10, 12-13.

Collected Works of Nana Asma'u, Daughter of Usman Dan Fodiyo pg 198-202, Educating Muslim Women: The West African Legacy of Nana Asma u 1793-1864 By Beverley Mack, Jean Boyd pg 34-35)

Educating Muslim Women: The West African Legacy of Nana Asma u 1793-1864 By Beverley Mack, Jean Boyd pg 85, 87)

Collected Works of Nana Asma'u, Daughter of Usman Dan Fodiyo pg 18-20

One Woman's Jihad: Nana Asma'u, Scholar and Scribe By Beverly B. Mack, Jean Boyd pg 63-75

Collected Works of Nana Asma'u, Daughter of Usman Dan Fodiyo pg 147, n. 344, Muslim Women: The West African Legacy of Nana Asma u 1793-1864 By Beverley Mack, Jean Boyd pg 46)

Collected Works of Nana Asma'u, Daughter of Usman Dan Fodiyo pg 28-31)

Educating Muslim Women: The West African Legacy of Nana Asma u 1793-1864 By Beverley Mack, Jean Boyd 69-70)

Educating Muslim Women: The West African Legacy of Nana Asma u 1793-1864 By Beverley Mack, Jean Boyd pg 81-84, Collected Works of Nana Asma'u, Daughter of Usman Dan Fodiyo pg 68-72)

Collected Works of Nana Asma'u, Daughter of Usman Dan Fodiyo pg 81-82, One Woman's Jihad: Nana Asma'u, Scholar and Scribe By Beverly B. Mack, Jean Boyd pg 48-49

One Woman's Jihad: Nana Asma'u, Scholar and Scribe By Beverly B. Mack, Jean Boyd pg 83-85-88

Collected Works of Nana Asma'u, Daughter of Usman Dan Fodiyo pg 70)

One Woman's Jihad: Nana Asma'u, Scholar and Scribe By Beverly B. Mack, Jean Boyd pg 76-79

Educating Muslim Women: The West African Legacy of Nana Asma u 1793-1864 By Beverley Mack, Jean Boyd pg 94)

Collected Works of Nana Asma'u, Daughter of Usman Dan Fodiyo pg 246, One Woman's Jihad: Nana Asma'u, Scholar and Scribe By Beverly B. Mack, Jean Boyd pg 40-43

Educating Muslim Women: The West African Legacy of Nana Asma u 1793-1864 By Beverley Mack, Jean Boyd pg 90-100, One Woman's Jihad: Nana Asma'u, Scholar and Scribe By Beverly B. Mack, Jean Boyd pg 36-37, 89

Collected Works of Nana Asma'u, Daughter of Usman Dan Fodiyo pg pg 245)

Educating Muslim Women: The West African Legacy of Nana Asma u 1793-1864 By Beverley Mack, Jean Boyd pg 101)

One Woman's Jihad: Nana Asma'u, Scholar and Scribe By Beverly B. Mack, Jean Boyd pg 79-83

Collected Works of Nana Asma'u, Daughter of Usman Dan Fodiyo pg 38, One Woman's Jihad: Nana Asma'u, Scholar and Scribe By Beverly B. Mack, Jean Boyd pg 23-25

Collected Works of Nana Asma'u, Daughter of Usman Dan Fodiyo pg 97)

Collected Works of Nana Asma'u, Daughter of Usman Dan Fodiyo pg 264)

Collected Works of Nana Asma'u, Daughter of Usman Dan Fodiyo pg 95-96

Collected Works of Nana Asma'u, Daughter of Usman Dan Fodiyo pg 250

Collected Works of Nana Asma'u, Daughter of Usman Dan Fodiyo pg 375-377)

Educating Muslim Women: The West African Legacy of Nana Asma u 1793-1864 By Beverley Mack, Jean Boyd pg 88-95)

Collected Works of Nana Asma'u, Daughter of Usman Dan Fodiyo pg 43, 49-50)

Educating Muslim Women: The West African Legacy of Nana Asma u 1793-1864 By Beverley Mack, Jean Boyd 107-108, 123, 130-131, Collected Works of Nana Asma'u, Daughter of Usman Dan Fodiyo pg 276)

Collected Works of Nana Asma'u, Daughter of Usman Dan Fodiyo pg 285

Collected Works of Nana Asma'u, Daughter of Usman Dan Fodiyo pg 289)

Collected Works of Nana Asma'u, Daughter of Usman Dan Fodiyo pg 283

Educating Muslim Women: The West African Legacy of Nana Asma u 1793-1864 By Beverley Mack, Jean Boyd pg 137-138)

Educating Muslim Women: The West African Legacy of Nana Asma u 1793-1864 By Beverley Mack, Jean Boyd pg 148)

Listed at the SOAS with the title ‘Ina gode Allah da yai annur na ahmada’ but is more likely to be the poem titled ‘Begore’ in Hunwick’s ALOA Vol.2, that opens with the line ‘Fa mu gode jalla da yayyi annur na Ahmada.’ The second poem is one of the recent discoveries by the Endangered archives program

Feminist or Simply Feminine ? Reflection on the Works of Nana Asma'u by Chukwuma Azuonye pg 72-73

Great read will share across Quora spaces, what I find interesting is while we can find African women warriors and rulers , finding an African female scholar is pretty rare or generally unknown to the public, matter of fact it's pretty rare find in most regions of the world, also while African learning centers had huge student bodies, I'm uncertain if they had female as part of the student body, although some universities were funded by wealthy women in both North Africa and West Africa.