Morocco, Songhai, Bornu and the quest to create an African empire to rival the Ottomans.

An ambitious sultan's dream of a Trans-Atlantic, Trans-Saharan empire.

The Sahara has for long been perceived as an impenetrable barrier separating “north africa” from “sub-saharan Africa”. The barren shifting sands of the 1,000-mile desert were thought to have constrained commerce between the two regions and restrained any political ambitions of states on either side to interact. This “desert barrier” theory was popularized by German philosopher Friedrich Hegel, who is largely responsible for the modern geographic separation of “North” and Sub-Saharan” Africa.

However, the Hegelian separation of Africa has since been challenged in recent scholarship after the uncovering of evidence of extensive trade between north Africa and west Africa dating back to antiquity, which continued to flourish during the Islamic period. Added to this evidence was the history of expansionist states on either side of the desert, that regulary exerted control over the barren terrain and established vast trans-Saharan empires that are counted among some of the world's largest states of the pre-modern era. Such include the Almoravid and Almohad empires of the 11th and 12th century which extended from southern Mauritania to Morocco and Spain, as well as the Kanem empire which emerged in southern chad and expanded into southern Libya in the 13th century.

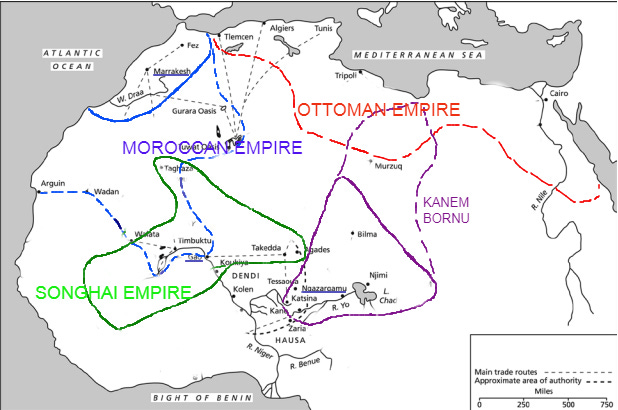

The era which best revealed the fictitiousness of the desert barrier theory was the 16th century; this was the apogee of state power in the entire western portion of Africa with three vast empires of Songhai, Kanem-Bornu and Morocco controlling more than half the region’s surface area. Their ascendance coincided with the spectacular rise of the Ottoman empire which had torn through north Africa and conducted campaigns deep into the Sahara, enabling the rise of powerful African rulers with internationalist ambitions that countered the Ottomans' own.

This article provides an overview of western Africa in the 16th century, the expansionism, diplomacy and warfare that defined the era’s politics and the outcome of one of Africa’s most ambitious political experiments.

sketch map of the empires mentioned in this article and their capitals

Support AfricanHistoryExtra by becoming a member of our Patreon community, subscribe here to read more about African history, download free books, and keep this newsletter free for all:

The rise of the Saadian dynasty of Morocco: conflict with the Ottomans, defeat of the Portuguese and plans of a west-African conquest.

The region of Morocco has been home to a number of indigenous and foreign states since antiquity, and its fortunes were closely tied with both Mediterranean politics and west African trade, but by the early 16th century this region was at its weakest point with several competing kingdoms controlling the major cities, European powers controlling many of its sea ports and stateless bands roaming the desert, one key player during this period of disintegration were the Portuguese.

The Portuguese had reoriented some of the west African gold trade south, and in the 15th century set their sights on colonizing morocco ostensibly as a holy war (crusade) that sought to establish a foothold in north Africa, after seizing the port city of ceuta, they gradually expanded their reach along the coast of Morocco south, upto the port city of Agadir 500km south, the reigning Wattasid dynasty only controlled the city of Fez and the surrounding regions upto the city of Marrakesh while the rest of the country was engulfed in internecine warfare.1 But by 1510, some of the warring groups in the sous valley (south-central Morocco) united under the leadership of Mohammad Ibn abd ar-Rahman; an Arab who claimed sharif status (ie: of the lineage of prophet Muhammad) and was the founder of the Saadi dynasty2 in an attempt to reverse Portuguese gains, his forces attacked the port city of Agadir, although this initial attempt ended in failure, it taught him the need to professionalize and equip his forces by relying on a standing army with fairly modern artillery rather than feudal levees on horseback3.

His successors; the brothers Ahmad al-Araj and Muhammad al-shaykh, managed to seize Marrakesh and hold it firmly despite Wattasid attempts at taking it back in 15254 by the 1540s, Muhammad al-Shaykh had flushed the Portuguese out of Agadir who fled the neighboring coastal cities of Safi and Azemmour as well, al-Shaykh now employed the services of “new Christians” in the city to manufacture his own artillery5, which brought him into conflict with his brother who had advanced north to conquer the Wattasids but failed, al-Araj tuned on al-Shaykh in a civil war that resulted in al-Araj’s defeat and exile, al-Shaykh then advanced onto Wattasid lands in 1545 and by 1549 seized their capital Fez making him the sole ruler of Morrocco.6

Rapidly advancing west from its conquest of Mamluk Egypt was the fledging Ottoman empire which had in the few decades of the early 16th century, managed to control vast swathes of land from Arabia to central Europe and Algeria, and in 1551, its armies invaded Morocco, routing the Saadian army and killing Mohammed al-Shaykh's son in the first battle7, in 1553, they reached Fez, ousting al-Shaykh and re-installing the Wattasids, only for him to return in 1554 and routing the Turks and their puppet dynasty whom he imprisoned.8

During this time, the Saadis were also making forays south into the southern Sahara with one that reached the city of Wadan in 1540 after a failed request by Ahmad al-araj to the Songhai emperor Askiya Ishaq I (r. 1539-1549) for the Taghaza salt mine9, added to this strife was the cold relationship between the Morrocans and the Ottomans which increasingly soured and by 1557, the Turks sent assassins to al-Shaykh's tent and he was beheaded.

the walls of the city of Taroudant, mostly built by Muhammad al-Shaykh

Al-Shaykh was succeeded by Abu Muhammad Abdallah who consolidated his father's gains and reigned peacefully until he passed in 1574, his death sparked a succession crisis between al-Maslukha who was proclaimed sultan and Abd al-Malik his uncle who fled to exile to the ottoman capital Constantinople, the latter took part in an Ottoman conquest of Tunis in 1574, and in return was aided by the ottoman sultan to retake his throne in Morocco, and on the arrival of his force at the capital Fez in 1576, al-Maslukha fled to Marakesh from where he was forced to flee again to the domain of King Phillip II of spain.10

when al-Maslukha's request for the Spanish king to aid his return to the Moroccan throne was turned down, he turned to the Portuguese king Sebastian, the latter had since built a sprawling empire in parts of the Americas, Africa and Asia and welcomed the idea of a Moroccan client state, and in 1578, Sebastian invaded morocco reaching several hundred miles inland at al-Kasr al-Kabir where he arrived with the exiled former sultan al-Maslukha to battle the armies of the reigning sultan al-Malik, but the Portuguese were defeated and their king killed in battle, as well as al-Maslukha and al-Malik himself in what came to be known as the “battle of the three kings”, thousands of Portuguese soldiers were captured by the Moroccans, all of whom were ransomed for a hefty sum by the new sultan Ahmad al-Mansur.11

The death of the Portuguese king eventually started the succession crisis that led to Spain subsuming Portugal in the Iberian unification under king Philip II. The ottomans had aided al-Malik who in return recognized the ottoman ruler Murad III as caliph and Morocco was thus formally under Ottoman suzerainty. But not long after his ascension, al-Mansur had the Friday prayer announced in his own name and minted his own coins as an outward show of his own Caliphal pretensions; actions that prompted his neighbor the Ottoman pasha of Algiers to persuade Murad to pacify Morocco to which al-Mansur quickly sent an embassy to Constantinople with what al-Mansur viewed as a gift but what Murad saw as an annual tribute, amounting to 100,000 gold coins, this “gift” halted Murad's attack on Morrocco in 1581, but was continuously paid over the following years.12

the Borj Nord fortress in the city of Fez, built by al-Mansur

While its hard to qualify morocco under al-Mansur as a tributary state of the Ottomans, this hefty annual payment was to an extent fiscally constraining. And while al-Mansur praised the Ottoman sultan with high titles in his correspondence, he tactically avoided recognizing him as caliph and instead emphasized his own sharif lineage which he buttressed with an elaborate intellectual project in morocco to shore up his rival claims as the true caliph,13 he also became increasingly deeply involved in European politics inorder to counter the Ottoman threat, particularly with the queen of England Elizabeth I who was looking for an alliance against Spain, the latter of which he may have hoped to invade and restore old Moroccan province of Andalusia, Morocco’s ties with England were further strengthened after al-Mansur witnessed the English queen's annihilation of the Spanish navy in 1588, and went as far as hoping a collaboration with her to seize Spain's possessions in the Americas and “proclaim the muezzin on both sides of the Atlantic”. In one of his correspondences with her around 1590, he wrote to Elizabeth that "we shall send our envoy as soon as the happy action of conquering Sudan is finished" “Sudan” in this case, referring to the region under the Songhai empire.14

Its was during this period around 1583 that the Moroccan sultan resumed his southern overtures to Taghaza (in northern Mali) and the Oasis towns of Tuwat (in central Algeria) preceding the invasion of Songhai as well as establishing diplomatic contacts with the empire of Kanem-Bornu.

The empire of Kanem-bornu: Mai Idris Alooma (r.1570-1603) between the Ottomans and the Moroccans

Kanem-Bornu was in the times of al-Mansur ruled by the Mai Idris Alooma, an emperor of the Seyfuwa dynasty that was centuries older than the Saadis, at its height between the 13th and 14th century, the empire of Kanem (as it was then known), encompassed vast swathes of land from zeilla in north-eastern Libya and all the lands of southern Libya (Fezzan) which were controlled at its northern capital Traghen, down to the the western border of the Christian Nubian kingdoms (in a region that would later occupied by the wadai kingdom); To its west it reached Takkedda in Mali and the controlled the entire region later occupied by the kingdom of Agadez, down to the city of Kaka west of Lake chad and into the territory known as Bornu in north-eastern Nigeria, ending in its capital Njimi in Kanem, a region east of Lake chad.15

Kanem's success largely owed to its ability as an early state with centralized control and military power that could easily conquer stateless groups all around its sides radiating from its core in the lake chad basin, these conquered territories were brought under its control albeit loosely, but in the late 14th century the empire’s model of expansionism was under threat with the rise of independent states which begun with its own provinces; its eastern district of Kanem rebelled and carved out its own state whose rulers defeated and killed several of the Bornu kings that tried to pacify it, by the 15th century however, the Bornu sultan Mai Ali Gaji (r. 1465-1497AD) and Mai Idris Katakarmabi (1497-1519) defeated the Kanem rebels, and established a new capital at Ngazargamu.16

During this upheaval, Kanem had lost parts of its western territories to the resurgent Songhai empire and much of the Fezzan was now only nominally under its fealty, it was ruled a semi-independent Moroccan dynasty of the Ulads (unrelated to the Saadis) whose capital was the city of Murzuk in 1550 although they were militarily and commercially dependent on Kanem bornu. The rulers of Bornu placed greater attention on the lands to their south and east particularly the city-states of the Hausalands and the cities of the Kotoko which were now brought more firmly under the empire’s suzeranity17

By 1577, the ottomans had conquered much of Libya including the Fezzan, which was strongly protested by Mai Idris who sent a number of embassies to the sultan Murad III in the late 1570s to recover the region but which amounted to little18, its within this context that Idris Alooma approached the Moroccan sultan in 1583 requesting arquebuses an offer that may have included a proposed alliance between Morocco and Bornu in the former’s conquest of Songhai.19

ruins of Mai Idris Alooma’s 16th century palace at Gambaru, near Ngazargamo

The empire of Songhai: from the glory days of Askiya Muhammad to the civil strife preceding its fall to the Moroccans

Songhai was the largest west African empire of the 16th century and one of the continent's largest in history, it was the heir of the highly productive and strategic core territory of the Niger river valley in which the preceding empires of Ghana and Mali in the 8th and 13th century were centered and from where they launched their expansionist armies south into the savannah and forest region and north into the desert regions, carving out vast swathes of land firmly under their control.

Like the Kanem empire, Ghana and Mali's imperial expansion succeeded largely because the regions into which they was expanding were mostly stateless at the time and relatively easy to conquer, and Songhai brought this expansionist model to its maximum; carving out a region lager than 1.6 million sqkm by the early 16th century, but the increasing growth and resistance of the smaller peripheral states effectively put a roof on the extent of Songhai’s expansion to its west and south and it soon shared a border directly with the empires of Kanem-Bornu to its east and the Saadian Morocco to its north. Songhai was at its height in the early 16th century under its most prolific emperor Askiya Muhammad (r. 1493-1528), the latter had within the first two decades of the 16th century conquered dozens of kingdoms stretching from Walata in southern Mauritania to Agadez in Niger, and from the Hausalands in northern Nigeria to the region of Diara in western Mali, as well as incorporating the desert region of northern Mali upto the town of Taghaza20.

The Askiya had also been on the Hajj to mecca in 1496 and met with several scholars and corresponded with the Mamluks in Egypt as well as the Abbasid Sharif who invested him with the title of Caliph, he therefore may have had internationalist ambitions although he didn't follow them up with embassies to any state unlike his neighbors21

In 1529, the ageing Askiya who was more than eighty years, was deposed by his son and a succession crisis embroiled Songhai that saw four Askiyas ruling in the space of just 20 years, but even in the midst of this, Askiya Ishaq I (r. 1539-1539) could strongly rebuff a Moroccan request for the control of the Taghaza salt mine, responding to the reigning sultan Ahmad al-Araj’s request for taxes accrued from Taghaza that "the Ahmad who would hear news of such an agreement was not he, and the Ishaq who would give ear to such a proposition had not yet been born", Ishaq then sent a band of 2,000 soldiers to raid the southern Moroccan market town of Banī Asbah22.

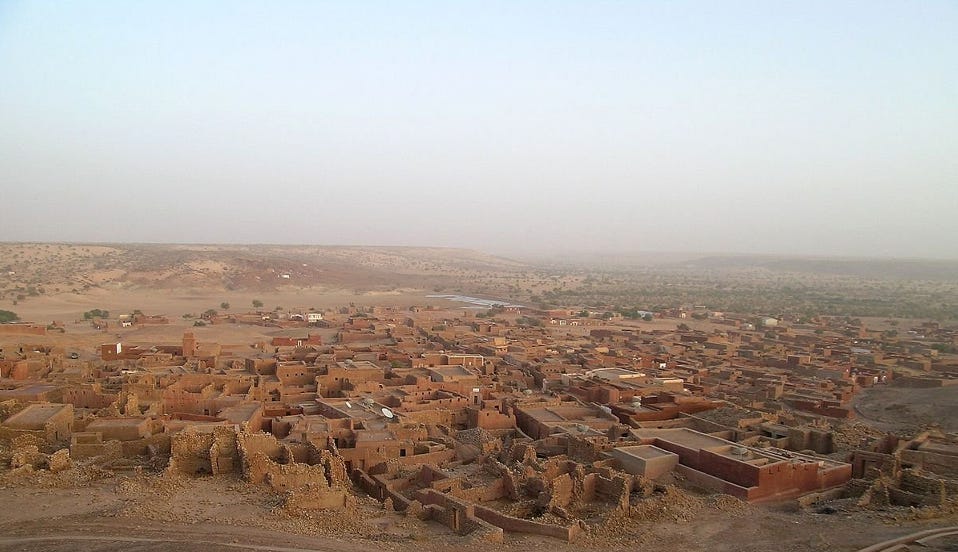

the town of Walata, one of Songhai’s westernmost conquests

The ascension of Askiya Dawud in 1549, whose reign continued until 1582, was followed by a period of consolidation and recovery from the centrifugal threats that had grown during the succession crisis, Dawud resumed Songhai's expansionism with a successful attack to its south-eastern neighbor Borgu and a failed attack on Kebbi (both in north-western Nigeria) between 1554 and 1559, he then moved south west to chip-away on parts of the faltering Mali empire in 1550 and 1570, sacking the Malian capital and pacifying Songhai provinces in the region near the sene-gambia region, he also campaigned into the deserts to his west and north as well as the region of Bandiagra (in central Mali) which was by then controlled by the Bambara23.

In 1556, the reigning Morrocan sultan Muhammad al-Shaykh developed interest in the Taghaza mine, allying with a local rival claimant to the Songhai governor of the town to kill the incumbent, although this brief episode didn't amount to much as the Moroccans soon withdrew,24 Decades later in the 1580s, the Moroccan sultan al-Mansur would request one year's worth of tax from Taghaza and it was sent (on only one occasion) 10,000 mithqals of gold by Askiya Dawud and the two rulers maintained cordial relationships25

After Askiya Dawud's passing in 1582, Songhai was once again embroiled in succession crises that saw three emperors ascending to the throne in just 9 years, in the midst of this, around 1585/1586, al-Mansur had sent a spy mission south to Songhai ostensibly as emissaries with gifts but these spies had been returned to Morocco with more gifts, soon after, al-Mansur sent two failed expeditions to capture the city of Wadan with 20,000 soldiers and the town of Taghaza with 200 arquebusiers, both of these cities were under Songhai control, al-Mansur also sent expeditions into the south-central Algerian cities of Tuwat and Gurara that were also unsuccessful.26

The reigning Askiya of songhai al-Hajji Muhammad (r. 1582-1586) was later deposed by his brothers led by Muhammad al-Sadiq (a son of Dawud) in favor of Askiya Muhammad Bani (r.1586-1587) whose rule was disliked by the same brothers that had installed him and they again fomented a rebellion against him, raising an army from the entire western half of the empire and marching onto the capital city Gao to depose him, but Askiya Bani died before he could fight the rebels and Askiya Ishaq II (r. 1588-1591) took the throne, it was then that the rebellious army approached Gao in 1588 and faced off with the Royal army, they were defeated by the Askiya Ishaq II in a costly victory with many causalities on both sides, a purge soon followed across the empire that sought to remove Muhammad al-Sadiq's supporters afterwhich, the Askiya resumed campaigning in the south west to pacify the region when the Moroccan armies arrived.27

15th century Tomb and Mosque of Askiya Muhammad in Gao

Diplomacy and minor skirmishes: Morocco, Kanem-Bornu and Songhai in a web of political entanglement with the Ottomans

i) Morocco:

The years between 1580 and 1591 were a period of intense diplomatic exchanges between Morocco, Kanem-Bornu, Songhai and the Ottomans, the earliest exchanges had been initiated by the two immediate Ottoman neighbors of Morocco and Kanem-Bornu especially to Murad III (r. 1574-1595), the Moroccans were more vulnerable in this regard than Kanem-Bornu and had in 1550 been directly invaded by the Turks who occupied fez in 1554, but the Moroccan sultan was unrelenting and when two embassies in 1547 and 1557 from Suleiman I reached morocco to request Muhammd al-shaykh's recognition of ottoman suzerainty (by reading Suleiman's name in the Friday sermons and stricking coins bearing his face) the proud Moroccan sultan replied : “I will only respond to the sultan of fishing boats when I reach Cairo; it will be from there that I will write my response.” not long after, assassins crawled into al-Shaykh's tent and severed his head, sending it to Constantinople.28

The succession crisis that ensued after his successor's death in 1574 brought to power the ottoman sympathizer al-Malik who owed his throne to Murad III, he mentioned Murad's name in the Friday prayer, issued coins with his face and paid him annual tribute, but on the ascendance of al-Mansur in 1578, Morocco's suzerainty to Ottomans was gradually reduced such that by the 1580s, he was virtually independent and begun requesting several rulers to recognize him as caliph instead, as well as establishing ties with European states, all inorder to create a rival caliphate centered on Morocco whose lands would stretch from Spain to Mali, and across the Atlantic into the Americas.29

a 17th century painting of Al-Annuri; who was sultan al-Mansur’s ambassador to England’s Elizabeth I, made by an anonymous English painter.

ii) Kanem-Bornu

In the years after they had secured the submission of morocco and thus completed the conquest of North africa, the Ottomans turned south and in 1577 invaded the region of the Fezzan, a region that was at the time ruled by the Ulad dynasty who had been a nominal client-state of Kanem-Bornu; the Ulads themselves had strong connections to the Hausa city of katsina as well as Kanem-Bornu and they fled after to both following each ottoman attack30

Although Bornu and the ottomans had been in contact prior to the latter's southern advance; the Mais of Kanem-Bornu had initiated contact with the Ottomans in the late 1550s with the pasha of Tripoli Dragut (r. 1556-1565) to request for acqubuses, but the invasion of the Fezzan by the Pashas who succeeded Dragut created a diplomatic rife between the two states and the Kanem-Bornu Mai Idris Alooma sent an embassy to protest this encroachment to which the Murad III responded "You are well aware that it is not one of the precepts of our mighty forefathers to cede any part of the citadels which have been in their hands" the correspondence he had with him however, seems to acknowledge that the Ottomans had gone further south than they should have but he resolved to retain the Fezzan regardless of this, he nevertheless ordered the pasha of Tunis to remain in good terms with Kanem-Bornu, and allow the safe passage of its traders, pilgrims and emissaries31.

Idris acquired several guns (arquebuses) as well as Turkish slaves skilled in the handling of these firearms, its unlikely that the ottomans handed them to him in sufficient quantities, rather, its said that Idris had captured the guns and the Turkish slaves from a failed Ottoman invasion into Kanem-Bornu32. Although the guns performance wasn't sufficiently decisive in the long run, they tilted the scales in favor of the Kanem armies in certain battles33, but since he had only acquired insufficient numbers of them, Idris sent an emissary to al-Mansur in 1582 with a letter requesting for guns and other military aid for Kanem’s campaigns, to which al-Mansur asked that the Kanem sultan mention his name in the Friday prayers and recognize him as caliph, an offer seemingly accepted by the Kanem ambassador in Marakesh (not Idris himself); the ambassador also said he hoped that al-Mansur would be guaranteed Kanem-bornu's aid to conquer songhai, although scholars have questioned the authenticity of this last account, which was entirely written by al-Mansur’s chronicler and seems to contradict the reality of how the war with Songhai later played out in which Kanem-Bornu wasn’t involved, although Kanem’s non-interference in the Songhai conquest may have been because al-Mansur didn’t send the guns Idris had requested.34

But its clear that Kanem-Bornu was well aware of the capacity of al-Mansur in the production of his own fire-arms as well as his rivalry with the Ottomans, Kanem-bornu may have also had less-than-cordial relationships with Songhai which had attacked some of its south-western vassals.

the fortified Kanem-Bornu towns of djado, djaba, dabassa and seggedim along its northern route to the Fezzan

iii) Songhai

Songhai had in 1500 conquered the Tuareg kingdom of Agadez and again in 1517, sacking the capital and imposing an annual tribute of 150,000 mithqals of gold (about 637kg)35, but this region may have earlier been under the orbit of the Kanem-bornu rulers who, despite their decline in the late 14th-15th century, considered it as part of their sphere of influence, its not surprising that in 1570s, Idris Alooma sent three expeditions against the Tuareg kingdom of Agadez and the later Mais of Kanem-bornu continued these attacks for much of the 17th century, a time in which Agadez seems to have remained firmly under the control of Kanem-Bornu which likely felt relieved from the Songhai threat36, added to this was the Askiya's invasion of the Hausa cities of Zaria, Kano and Katsina between 1512-1513, all of which had since the mid-15th century, been firmly under Kanem-bornu's suzerainty, this invasion would not have gone unnoticed by the Kanem rulers, especially after the rebellion of a Songhai general, Kotal Kanta who ruled from Kebbi, seized most of the Hausalands and routed several Kanem and Songhai attacks on his kingdom until his death in the 1550s afterwich Kanem-Bornu returned to reassert its authority over some of the cities but was only partially successful as Kebbi and Katsina remained outside its orbit37

By the 1590s, Kebbi seems to have returned to Songhai's orbit and there are letters addressed to its ruler from al-Mansur who requested that the Kanta pays allegiance to him as caliph (accompanied with threats to invade Kebbi), but these were rebuffed and Kebbi aided Songhai in its fight against the Moroccans38. Needless to say, when the Moroccan sultan was making plans to invade Songhai, the Kanem-Bornu Mais likely hopped this would eliminate their western threat.

sections of the old town Agadez. It was mostly under Songhai control for much of the 16th century but fell under Kanem-Bornu’s orbit in the 17th century

The fall of Songhai and its aftermath: a pyrrhic victory

In 1590, an royal slave of the Askiya fled to Marrakesh where he claimed he was a deposed son of Dawud and a contender to the Songhai throne, he met with al-Mansur and provided him with more information about Songhai (supplementing the information received by al-Mansur’s spies), the Moroccan sultan then sent a request for reigning Askiya Ishaq II to pay tax on the Taghaza salt mine claiming the money was his on account of him caliph, and saying that his military success had protected Songhai from the European armies (in an ironic twist of fate given since he was about to send his own armies against Songhai, and it was a rather empty excuse given than European incursions were infact defeated in the Sene-gambia region more than a century before this); the Askiya rebuffed his request, sending him a spear and a pair of iron shoes knowing al-Mansur’s intent was war.39

Al-Mansur’s declaration of war was initially opposed in Morocco where the sultan al-had developed a reputation of a very shrewd politician who was known to be harsh to both his subjects and courtiers; once saying that "the Moroccan people are madmen whose madness can only be treated by keeping them in iron chains and collars"40, his courtiers and the ulama of Morocco objected to his invasion claiming that even the great Moroccan empires of the past had never attempted it, but al-Mansur assured them of success of his fire-arms and said that those past dynasties were focused on Spain and the Maghreb, both of which are now closed to him to which the notables agreed to his conquest.41

In 1591, al-Mansur sent a force of 4,000 arquebusiers and 1,500 camel drivers south, under the command of Jawdar, they were met by a Songhai army about 45,000 strong, a third of which was a cavalry unit, the Askiya's army was defeated but a sizeable proportion retreated to Gao and then eastwards to the region of Dendi from where it would continuously mount a resistance.42 A 17th century chronicler in Timbuktu described the aftermath of Songhai’s fall; "This Saadian army found the land of the Sudan at that time to be one of the most favoured of the lands of God Most High in any direction, and the most luxurious, secure, and prosperous, but All of this changed; security turned to fear, luxury was changed into affliction and distress, and prosperity became woe and harshness". Jawdar sent a letter to al-Mansur about the Askiya Ishaq's escape and the Songhai ruler’s offer of 100,000 mithqals of gold and 1,000 slaves for the Moroccans to return to their land, al-Mansur was however insistent on the Askiya's capture, sending a new commander named Pasha Mahmud with 3,000 acqubusiers to complete the task. He arrived in Timbuktu in 1591, deposed jawdar and once in Gao, he built boats to cross the river and attack the Askiya in Dendi, the pasha fought two wars with the Askiya both of which ended with the latter's retreat but failed to meet al-Mansur's objective.43

Askiya Ishaq was deposed in favor of Aksiya Gao who became the new ruler of Dendi-Songhai but he was later tricked by Mahmud into his own capture and death a few months after his coronation, and the Dendi-Songhai court installed a new ruler named Askiya Nuh who was successful in fighting the Moroccans, killing nearly half of the arquebusiers sent to fight him44.

Having failed to conquer Dendi-songhai, the Pasha Mahmud tuned his anger on the Timbuktu residents, he seized the the scholars whom he shackled and had their wealth confiscated, but squandered much of it between his forces and sent a paltry 100,000 mithqals of gold (500kg) to al-Mansur (a measly sum that compared poorly with the 150,000 mithqals Songhai received from Agadez alone). On reaching Marakesh, the Timbuktu scholars and informants of al-Masnur reported pasha Mahmud's conduct and al-Mansur sent orders for him to be killed and the scholars were released not long after, Pasha Mahmud then went to Dendi to fight Askiya Nuh with a force of over 1,000 arquebusiers but was defeated and his severed head was sent to Kebbi to be hung on the city walls.45

the city of Djenne, a site of several battles between the Armas and various groups including the Bambara and the Fulani as well as the declining Mali empire, it was by 1670 under the control of the Bambara empire of Segu

In the 30 years after their victory in 1591, the al-Mansur continued to send arquebusiers to fight the Askiyas totaling up to 23,000 men by 1604, only 500 of whom returned to Marakesh, the rest having died in battle, some to diseases and the few hundred survivors garrisoned in the cities of Djenne, Timbuktu and Gao46. By 1618, the last of the Moroccan pashas was murdered by his own mutinous soldiers47 (who would then be known as the Arma), these Arma now ruled their greatly diminished territory independently of Morocco which had itself descended into civil war, this territory initially comprised the cities of Djenne, Timbuktu and Gao but the hinterlands of these cities were outside their reach, by the 1649, the cities Timbuktu and Gao were reduced to paying tribute to the Tuareg bands allied with the Agadez kingdom48, and by 1670s both Djenne and Timbuktu were paying tribute to the Bambara empire centered at Segu.49

Gao was reduced from a bustling city of 100,000 residents to a forgotten village slowly drowning in the sands of the Sahara, the great city Timbuktu shrunk from 70-100,000 to a little over 10,000 inhabitants in the 18th century, the vast empire that al-Mansur dreamt of fizzled, Morocco itself was plagued by six decades of civil war after his death with 11 rulers ascending in just 60 years, more than half of whom were assassinated and deposed as each ruler carved up his own kingdom around the main cities while bands roamed the surrounding deserts and Europeans seized the coastal cities, while minor raids to the region of Adrar in (western Mauritania) were resumed intermittently by the Moroccans in the 18th century50 when the Alwali dynasty reunified Morocco, the Moroccan overtures into west-Africa on the scale of the Songhai invasion were never repeated and its activities were constrained to propping up bands of desert warriors in the western Mauritania51. west-Africa's political landscape had been permanently altered as new states sprung up all around the southern fringes of the former Songhai territory, and several scholarly and commercial capitals rose such as Segu, Katsina, Kano and Agadez boasting populations from 30,000-100,000 residents in the 18th century.

the ruins of Ouadane, after a series of Moroccan expeditions into the Adrar region the 17th and 18th century, the city was largely abandoned

Conclusion : Assessing the legacy of one of Africa’s most powerful rulers

The Moroccan armies of al-Mansur lacked the capacity to incorporate the large Songhai territory into their empire despite their best efforts and the commitment of the sultan to his grand objectives, their soldiers usually found themselves on the defensive, holed up in garrison forts in the cities in which even the urban residents, the scholars and attimes their own soldiers considered them unwelcome.

The over 23,000 Moroccan soldiers the al-Mansur sent to their graves in Songhai reveal the commitment that the sultan had to his Caliphal empire, a grandiose vision which flew in the face of the political realities he was faced with, since his own army numbered no more than 30-40,000 at its height, the loss of tens of thousands of his best armed men was a large drain to his internal security as well as the state purse. Once the shock factor of the guns had worn off, the Armas were rendered impotent to the attacks of the Askiyas, the Tuaregs, the Bambara, the Fulani who repeatedly raided their garrisons in the cities where they were garrisoned, and in less than a few decades, upstart states armed with just spears and arrows, and bands of desert nomads reduced the hundreds of well-armed soldiers to tributary status. A similar experience with guns had been witnessed by Idris Alooma of Kanem-Bornu, as well as the atlantic African states like Esiege of Benin who soon learned that the new weapons were never decisive in warfare (atleast not until the late 19th century). Al-Mansur's ambition to create a western caliphate that would rival the Ottomans exceeded the resources he possessed to accomplish this goal, and in the process set back the regions of Morocco and the Songhai for nearly a century52.

In 1593, al-Mansur finished the construction of a dazzling new palace of el-Badi, partly with the wealth taken from Songhai, but in 1708, a different Moroccan sultan from a different dynasty tore it down in an act of jealousy53; like his dream of a trans-Saharan, trans-Atlantic empire; the legacy of al-Mansur lay desolate, in a pile of ruins.

the el-badi palace in Marakesh

for more on African history including the longest lasting trans-saharan empire of Kanem, please subscribe to my Patreon account

Roads to Ruin by Comer Plummer pg 3

Conquistadors of the Red City by Comer Plummer pg 19

Roads to Ruin by Comer Plummer pg 11)

Roads to Ruin by Comer Plummer pg 15)

Roads to Ruin by Comer Plummer pg 19-25, 28-29)

Roads to Ruin by Comer Plummer pg 25-30)

Roads to Ruin by Comer Plummer pg85)

Roads to Ruin by Comer Plummer pg 86)

Conquistadors of the Red City by Comer Plummer pg 20-21)

Africa from the Sixteenth to the Eighteenth Century by UNESCO IV pga 202-204)

Africa from the Sixteenth to the Eighteenth Century by UNESCO general history IV pg 205-210)

Reviving the Islamic Caliphate in Early Modern Morocco by Stephen Cory, pg 65; and Ahmad Al-Mansur: Islamic Visionary by Richard L. Smith - Page 57

reviving the islamic caliphate in Early Modern Morocco by Stephen Cory pg 70-85

Britain and the Islamic World, 1558-1713 by Gerald M. MacLean and Nabil Matar pg 50-59

Africa from the Sixteenth to the Eighteenth Century by UNESCO general history iv pg 100)

The kingdoms and peoples of Chad by Dierk Lange pg 259-260

West Africa During the Atlantic Slave Trade by Christopher R. DeCorse pg 110-112

Mai Idris of Bornu and the Ottoman Turks pg 471

reviving the islamic caliphate in Early Modern Morocco by Stephen Cory pg 121-123)

African Dominion by Michael A. Gomez pg 236-245)

Timbuktu and the Songhay Empire by John Hunwick pg 103-107

African Dominion by Michael A. Gomez pg 331)

African Dominion by Michael A. Gomez pg 336-339)

Timbuktu and the Songhay Empire by John Hunwick pg 151)

Timbuktu and the Songhay Empire by John Hunwick pg 155)

reviving the islamic caliphate in Early Modern Morocco by Stephen Cory pg 123)

Timbuktu and the Songhay Empire by John Hunwick pg 157-178)

Roads to Ruin by Comer Plummer pg 82- 88)

The Man Who Would Be Caliph by S Cory pg

Slaves and Slavery in Africa: Volume Two By John Ralph Willis pg 62-65

Mai Idris of Bornu and the Ottoman Turks by BG Martin pg 482-490

Timbuktu and the Songhay Empire by John Hunwick pg 327

Warfare & Diplomacy in Pre-colonial West Africa by Robert Sidney Smith pg 82)

The Man Who Would Be Caliph by S Cory pg 187-189)

Timbuktu and the Songhay Empire by John Hunwick pg 108, 113, 26

The Cambridge History of Africa: From c. 1600 to c. 1790, by Richard Gray pg 122-124)

Government In Kano, 1350-1950 by M.G.Smith pg 137-141)

Timbuktu and the Songhay Empire by John Hunwick pg 304)

Timbuktu and the Songhay Empire by John Hunwick pg 186-187)

Conquistadors of the Red City Comer Plummer III pg 236

reviving the islamic caliphate in Early Modern Morocco by Stephen Cory 127-128

Timbuktu and the Songhay Empire by John Hunwick pg 189-191)

Timbuktu and the Songhay Empire by John Hunwick pg pg 195-199)

Timbuktu and the Songhay Empire by John Hunwick pg 204)

Timbuktu and the Songhay Empire by John Hunwick pg 227),

Timbuktu and the Songhay Empire by John Hunwick pg 245)

Timbuktu and the Songhay Empire by John Hunwick pg 257)

Muslim Societies in Africa by by Roman Loimeier pg 73)

Essays on African History: From the Slave Trade to Neocolonialism By Jean Suret-Canale pg 30

Desert Frontier by James L. A. Webb pg 47-49

The Atlantic World and Virginia by Peter C. Mancall pg 157-168

The Man Who Would Be Caliph by S Cory pg 195-199)

reviving the islamic caliphate in Early Modern Morocco by Stephen Cory pg 225

Great Article. Very informative and Helpful

Amazing article! This has to be one of my favourites yet!